Abstract

A large body of evidence suggests that sustainable destination development (SDD) is not only multidisciplinary but interdisciplinary as its research involves the integration of knowledge, methods, theories or disciplines. The word inter- is a “dangerous” one as it implies a “dangerous connection” attempting to reconcile irreconcilable people (i.e., North institutions and South institutions), but it is also very inclusive as, for example, economic behavior is related to social background and cultural issues. Although a common view is that SDD is interdisciplinary, what disciplines does it cross exactly? With the attendant “semantic confusion”, research on SDD is working in different directions, but what exactly does the existing research take as its object of study? What are the leading themes and perspectives in the field? How do we evaluate these diversification efforts? Trying to add one more seems redundant. We believe that after nearly two decades of productive scholarship, it is now time to try to identify some potential paradigms in SDD. A content-analysis-based literature review to explore previous studies is undoubted of value, as these diverse efforts point to current trends in SDD research. Therefore, we conducted an exploratory and descriptive analysis of the literature on SDD from 2015–2020 to provide specific indications for its interdisciplinary character. As a result, a total of 175 articles in 31 crucial journals from 2015 to 2020 are reviewed. Based on content analysis, five leading themes and five leading perspectives in the SDD literature were identified. We adopted an immanent critique method to discuss our findings. We appeal for consensus instead of definition and balance instead of choice in the discourse of SDD. We suggest ways in which past academic research can be used smartly and point out some important but neglected areas to stimulate a more creative research production.

1. Introduction

Over the past few decades, the research and debate on what “sustainability” is, from the concept of sustainable development to sustainable tourism, has generated great interest from both traditional and emerging disciplines. The integration and exchange of knowledge from these disciplines have made outstanding contributions to what sustainable destination development means and how to best achieve it. Some of the highlights include Saarinen’s (2006) [1] three pillars of sustainable development and the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Before examining the interdisciplinarity of sustainable destination development (SDD), it is necessary to understand what SDD is. First of all, what is sustainability? Brundtland Report defends sustainability: “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [2]. It proposes to guide the current development with the smallest negative impact to satisfy the wellbeing of present and future generations. Since the Brundtland report introduced the concept of sustainability into the global political agenda, the idea of sustainable development has been widely popularized in the tourism field. Then what is sustainable tourism? The World Tourism Organization defines sustainable tourism as “meets the needs of present tourists and host regions while protecting and enhancing opportunities for the future … leading to management of all resources in such a way that economic, social, and aesthetic needs can be fulfilled while maintaining cultural integrity, essential ecological processes, biological diversity, and life support systems.” [3]. This definition combines the economic, social and environmental perspectives of sustainable tourism with the practical consideration that tourism decision-makers are usually more concerned with creating economic growth [4].

Due to the vagueness and complexity of the terms of sustainability and sustainable tourism, some scholars often confuse the two. Although both terms recognize that economy, environment, and society are inescapably interlinked, sustainability does not imply that economic growth is indispensable or that economic growth inevitably causes harm to the net environment [5]. Since the term sustainable destination development also acknowledges that the growth of tourism should be limited, its meaning seems to be closer to sustainable tourism. Departing from sustainability and sustainable tourism, sustainable destination development, an emerging field of research, has a complex conceptual structure and has been abused and condemned due to its vague characteristics and definitions [5].

We are not trying to define what sustainable destination development is because the discourse of sustainable destination development is still being “created”. This is a dynamic process and should not be viewed as a conceptualized and validated thing [6]. Nonetheless, it boils down to a struggle between discussion and control, which is an inherently ideological process [7], as evidenced internationally. The previous literature reflects the “foundations” of its particular parts: economics, ecology, environmental management, environmental philosophy, geography, law, business, philosophy, etc.

Although sustainable destination development involves multiple disciplines, there is extensive evidence that sustainable destination development is not only multidisciplinary but interdisciplinary [8], which needs to be emphasized as the starting point of this research. In a broad sense, interdisciplinary research has designed different disciplines to jointly promote the mutual development of the scope and methods of research problems. In the broad sense, inter-disciplinarity refers to a broad category encompassing inter-, trans-, multi- and cross-disciplinarity. The reason why sustainable destination development is interdisciplinary rather than multidisciplinary is that its research involves different disciplines coming together to enable mutual development on the scopes and approaches of the research problem. Moyle et al. (2014) [9] also confirmed this argument as: “Sustainable tourism involves a holistic, integrated and long-term planning approach”. The core of the interdisciplinary concept is integration, such as the integration of knowledge, methods, theories, or disciplines. In sharp contrast, there is hardly any exchange of technology or knowledge between disciplines in multidisciplinary research [8].

Within sustainable destination development, the interdisciplinary nature is thought to arise out of the nature of “real-world” issues. Kates (2011) [10] ‘s view of “What kind of science is sustainable development?” clarifies the characteristics of this new field: ““sustainability science is a different kind of science that is primarily use-inspired… with significant fundamental and applied knowledge components, and commitment to moving such knowledge into societal action.” It is, therefore, more important to understand the practical areas in which sustainable destination development is applied.

Although a common view is that sustainable destination development is interdisciplinary, what disciplines does it cross exactly? What are the leading themes and perspectives in the field? The word “inter-” is a dangerous word because it implies a “dangerous connection.” [11], attempting to reconcile irreconcilable people and things [12]. Sustainable destination development (SDD) is based on a vague and seemingly contradictory framework (ecological sustainability vs. development/growth), emitting complex, different, but conflicting theoretical perspectives, with the consequent “semantic confusion” [12]. It has been used and generally accepted as if it had “universality and time-validity” [13], but at the same time, it is hard to pinpoint exactly what it is.

Much research on sustainable destination development is going on in different directions, but what exactly does the existing literature study? How can we understand these diversification efforts? Trying to add one more seems redundant [8]. We believe that after nearly two decades of productive scholarship, it is time to try to identify some potential examples of sustainable destination development. As Imre Lakatos (1978) [14] said, “The premise of judging the direction of progress or degradation of scientific research is the concept of paradigm”. These diverse efforts point to the current trends in sustainable destination development research, so a research review to explore previous research is undoubtedly useful.

Therefore, we conduct an exploratory and descriptive analysis of the literature on sustainable destination development from 2015–2020 to provide specific indications for its interdisciplinary character. We are interested in how tourism and partnership fields apply to the specific case of sustainable destination development, especially in understanding what the leading themes and perspectives that inform this subject area are and why. We raise the following three research questions:

- In the past five years, what are the leading themes of sustainable destination development research?

- What are the leading perspectives under these leading themes?

- How do these leading themes and perspectives imply the interdisciplinary characteristics of sustainable destination development?

As a result, a total of 175 articles in 31 crucial journals from 4 mainstream online databases (Taylor and Francis, Wiley, Elsevier, MDPI) from 2015 to 2020 were reviewed. Based on content analysis, this study identified five leading themes in the sustainable destination development literature: tourists, destination branding, destination cooperation, digitization, community and tourism, and destination governance. In addition, through analyzing the perspectives of these leading themes, this study identified five leading perspectives: (1) symbol, image and place attachment; (2) spiritual retreat tourism increases visitor satisfaction; (3) smart tourism; (4) stakeholder destination cooperation (innovation, destination update, crisis management and cross-border cooperation); (5) tourists’ psychology and decision-making (destination selection, willingness to pay). Finally, the internal linkages of these findings and implications for the future of sustainable destination development research are discussed.

2. Methodology

We begin with ontological and epistemological considerations [15]. As stated in the introduction, sustainable destination development is a dynamic and being created field in which emerging social phenomena and categories through social interaction are in a state of constant revision [15]. Constructivism is an ontological position that essentially invites researchers to consider social reality as the way in which social actors continue to achieve, rather than something external to social actors that completely limits them [15]. In order to understand its interdisciplinary character, a content-analysis-based literature review is a good systematic review approach that can “map and evaluate existing areas of knowledge and specify research questions to further develop existing bodies of knowledge”, according to Calogero (2011) [16]. Calogero (2011) [16] describes this approach as identifying “key scientific contributions”, reducing bias and “providing collective insights”. Caulley (2007) [17] recommends this approach as a structured and consistent process for producing reliable discoveries. Given the high relevance of this approach to the purpose of this study, a content-analysis-based literature review method was employed.

2.1. Material Selection

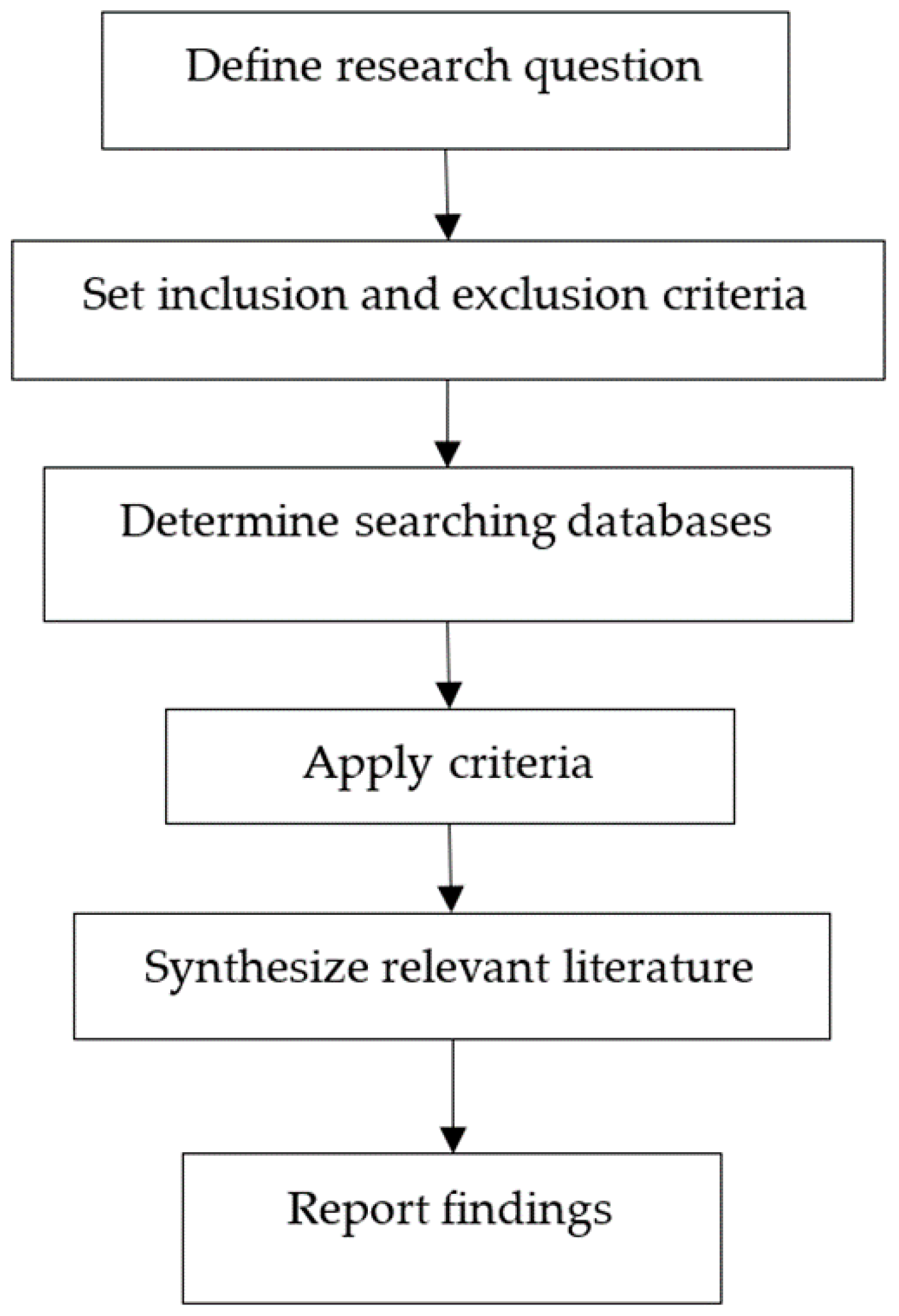

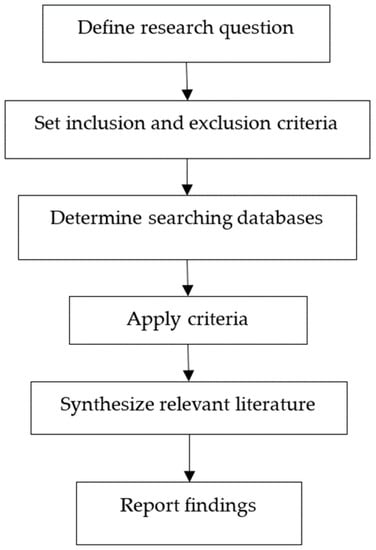

We used the six-stage optimization process Seuring, and Gold (2012) [18] suggested to collect the data (see Figure 1), including: defining research questions, setting inclusion and exclusion criteria, determining search databases, applying criteria, integrating relevant literature, and reporting findings. First, the research questions were raised, which is one of the earliest steps that can be found in the introduction. Then, we utilized a retrieval strategy to benefit our research results from a focus on peer-reviewed papers, and thus we defined a search string by querying a set of related keywords. The keywords are “sustainable destination”, “sustainable destination development”, “destination development”, “tourist destination”. These keywords were applied in the relationship of “or” instead of “and” to avoid unnecessary repetition. Taking into account the article’s audience, popularity, quality, and relevance to tourism research, we applied the defined search string to four mainstream publishers (Taylor & Francis, Wiley, Elsevier, MDPI). The online databases of these four publishers were chosen because they are one of the most popular publishers that are highly relevant to the travel industry. The reason for using the publisher’s online database for searching, rather than using other broader search engines, such as Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar, etc., is to make it possible to select pure scientific articles. We applied this set of keywords to the keyword search engines of the four major publisher databases to find matching research articles. These articles are judged to be suitable for publication according to the quality of blind peer review and meet strict theoretical and methodological requirements. We searched for articles from January 2015 to December 2020 (not including December because the data collection was completed on 8 December). We excluded unpublished papers on sustainability and publications of work by governments, countries and international organizations interested in sustainability. Although estimates in other fields indicate the severity of this bias, this approach may lead to bias by excluding certain disciplines or more controversial research. In the third step, we excluded duplicate papers and applied inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Table 1). As of the end of data collection on 8 December 2020, we have found a total of 175 articles matching the keywords in the online databases of the four major publishing houses (see Table 2). The final 175 papers were classified and evaluated through content analysis, which is a systematic and objective research method for quantifying phenomena, documents or communication [17].

Figure 1.

Paper selection process suggested by Durach et al. (2017). Source: [19].

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 2.

Databases, journals and articles reviewed.

2.2. Content-Based Literature Review Analysis

Content-based literature review analysis can be broadly divided into two levels. The first is to explore and mine the potential content of the text, and the second is to analyze the list content of the text by descriptive statistics. This method reflects the special advantage of a content-based literature review analysis method; that is, it combines the qualitative method retaining rich meaning with powerful quantitative analysis [20].

At the first level of qualitative analysis, we used a grounded approach. Neuendorf (2002) explained the overall goal of content analysis “identify and record the relatively objective (or at least intersubjective) characteristics of a message” [21]. The grounded approach suits our research since we do not and cannot identify an existing framework. Instead, our goal is to establish a conceptual framework to outline current trends in sustainable destination development research. The grounded approach focuses on discovering new theoretical insights and innovations, and avoids traditional logical deductive reasoning [22], and is regarded as “emerging explicitness” [23]. We used the qualitative analysis software NVivo to perform line-by-line coding on all the included documents and openly decompose, check, compare, conceptualize and classify the content of the documents [24]. We reread the data several times to understand the data and break it down into a manageable form. In the third step, we performed axial coding. After opening the code, the data were compared, similar events were grouped together, and the same concept labels were given. Dey (1999) [25] conceptualizes this process of grouping concepts at a higher and more abstract level as “categorizing.” This process further categorizes and narrows the themes. Finally, we performed selective coding by we counted the results of the coding and selected the top six in the ranking as core categories. This core category selected is systematically related to other categories, validating those relationships and filling in categories that need further refinement and development [24].

2.3. Reliability and Validity of Content Analysis

Brewerton and Millward (2001) [26] proposed that the results of content analysis are quite controversial if they are based only on the multiple judgments of a single researcher. With this in mind, in this study, multiple researchers participated in content analysis. This method, according to Duriau et al. (2007) [20], can greatly improve the effectiveness and reliability of (literary) sampling and data analysis and can distinguish the search for lists or potential content. The decontextualization of content analysis results and theory-led abstraction can require a certain degree of generalization of findings, which can prove external validity (Avenier, 2010) [27]. In addition, by carefully recording the entire research process, the transparency and reproducibility of the research design can be ensured.

2.4. Descriptive Analysis

After the content analysis, we also used the descriptive analysis method to supplement the content analysis. We exported the attributes associated with the defined articles to Microsoft Excel. These relevant attributes include publishing practices, methodology used, and theories involved, etc., which provide valuable information to supplement the results of content analysis. It complementary and valuable information to the results of the content analysis to gain a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon being investigated [28]. Limitations of the method used in this study are pointed out at the end of the paper.

3. Content Analysis Results: Themes and Perspectives

3.1. Leading Theme 1: Tourist

Tourist is the most leading research theme for sustainable destination development, accounting for 17.14% of the total literature, of which there are three leading perspectives: tourist satisfaction (50% of the theme), tourist psychology and decision-making (30% of the theme) and tourist ethics (20% of the subject).

3.1.1. Tourist Satisfaction

Both physical tourism services and spiritual tourism services have proved to be effective ways to increase tourist satisfaction. Physical tourism that focuses on food, wine, and agricultural products plays a role in enhancing the brand image of the destination and building community pride related to food and local culture (i.e., [29,30]). The connection between regional cuisine and culture, history and identity show tourists the authenticity of the destination, enabling consumers to generate conversations and images, gain knowledge, and provide opportunities for the creativity and entrepreneurial spirit of small entrepreneurs and local craftsmen to eventually establish tourists’ image of the destination and their destination loyalty [29,30].

On the other hand, spiritual retreat tourism is part of health and wellness tourism and refers to activities that encourage and help tourists change their quality of life through yoga or spiritual retreat (i.e., [31,32,33,34]). Spiritual retreat tourism’s contribution to sustainable destinations is that it cannot only help tourists discover spiritual self-awareness [32] but also prevent environmental damage because activities must be carried out in natural environments [31]. Moreover, spiritual retreat tourism also brings special value benefits to nature because these places are always located in unique pure and green landscapes, such as rural areas and places with spa history (for example, Rotorua, New Zealand) [33].

The literature on spiritual retreat tourism provides two insights: first, considering the influence of spiritual retreat tourism on the values of tourists, different tourism experiences should be designed to transform the sustainable values of tourists; second, the spiritual retreat tourism should be based on the community’s perspective and emphasize the result of the tourists’ spiritual recovery.

3.1.2. Travel Ethics

Vulnerable destination tourism was born out of tourists’ morality and compassion, among which the leading themes are post-crisis destination tourism (including volunteer tourism) and last chance tourism (LCT) (i.e., [35,36,37]).

Part of the reason visitors visit these last chance destinations (such as glaciers) is that they believe that climate change will negate the opportunity to experience these places in a real, original way in the future [38]. In this way, visitors can establish a location-based connection with the destination [35] and get a sense of accomplishment, which is strongly reflected as “a reason to live” [39]. However, by visiting these remote last-chance tourism destinations, the last chance also seems to indicate that tourists are not aware of the damage caused by their high-carbon tourism, do not have such affordability, or are able to defend themselves [38].

The literature on vulnerable destination tourism generated by ethics provides two insights: first, tourist sympathy for disaster destinations can be used for destination marketing and gain a competitive advantage in the destination; second, the moral paradox of the last chance tourism makes it produce huge carbon emissions while achieving tourist ecological education.

3.1.3. Tourist Psychology and Decision

Tourists’ psychology determines their decision on the destination and whether they will return to the destination. Interaction ritual (IR) and related emotional energy lead to unforgettable experiences, which leads to repeat tourism Sterchele (2020) [40]. Scholars have also studied tourists’ willingness to pay, choosing overload effects and perception of congestion. The literature of tourists’ psychology and decision-making provides insight that the consistency between the material produced by the destination market and the tourist’s self-consciousness in the early-stages counter-intuitively blocks the decision-making process, thus producing repeat tourism and sustainable decision-making at the destination.

| Perspective | Examples | Studies under This Perspective | |

| Tourist satisfaction | Physical tourism services increase tourist satisfaction | Han et al. (2020) [29] investigated the relationship between Chinese tourists’ satisfaction with destination cuisine and sustainable tourism destination development based on explanatory research and found that agricultural products and cuisine drive tourist expectations and improve tourists’ experience satisfaction, which is conducive to creating a sustainable destination image. | [30,41] |

| Spiritual service increases tourist satisfaction | Nuray and Yuksel (2020) [42] identified the opportunities and challenges of using slow philosophy in the development of tourism from the perspective of the supply side of Latvia, explaining that slow tourism has potential for destination sustainability; that is, it cannot only promote sustainable tourism and economic development in the region but also enhance the capacity of local stakeholders. | [31,32,33,34,42,43] | |

| Travel ethics | Wearing et al. (2020) [36] examined the recovery of tourism in Nepal after the 2015 earthquake and found that voluntary tourism can be recovered in various destinations, such as Nepal. The last chance tourism (LCT) market is built around moral paradoxes (Stephen et al. 2020). | [36,37] | |

| Tourist psychology and decision | Jeuring and Haartsen (2018) [44] investigated residents of the Friesland province in the Netherlands and then concluded their performance in choosing vacation destination preferences based on their attitudes to destinations and distance factors ((1) short distance tourists, (2) long-distance tourists, (3) middle-distance tourists and (4) mixed tourists). | [33,39,44,45] | |

3.2. Leading Theme 2: Destination Branding

Destination branding is the second leading theme in sustainable destination development research, accounting for 16% of the total literature, of which the main perspectives are from DMO (25% of the theme), tourist (64.29% of the theme), and supplier (10.71% of the theme).

3.2.1. From DMO Perspective (Events and Activities)

DMO’s contribution to the sustainable development of destinations by organizing events and activities in cooperation with local stakeholders is not only to support rural communities [46], to affect the economic wealth of the region, but also to create local history and culture experiences for tourists. For example, Ziakas (2020) [47] proposed that DMO should cooperate in developing a framework to utilize the event portfolio and create a foundation for the destination’s tourism products and achieve the purpose of tourist education. The literature on destination branding from the perspective of DMO provides insights that DMOs are ought to value the role of food and drink tourism in supporting communities, creating tourist experiences, solving ecological problems and increasing regional economic wealth. Moreover, DMOs are suggested to develop distinctive tourism or activities based on local products.

3.2.2. From the Perspective of Tourists (Symbols, Images and Place Attachment)

Iconology and semiotics are used in destination brand research. The destination image generates a tourist’s attachment to the destination, resulting in the tourist’s loyalty to the destination. The establishment of icons and symbols can be based on urban architecture [48]; rural scenery [49]; international companies related to the location [50]; advertising [51]; animals and plants [52]; movies [53]; activities; communities [54]; cultural heritage [55]; and astronomy [56]. Almost all the literature clarifies the positive effects of destination images on destination loyalty. The place attachment of tourists generated by the symbol will improve the self-esteem of residents and increase community cohesion by alleviating the conflict between residents and tourists, and promote the economic development of destinations by generating destination loyalty. Destination branding literature from the perspective of tourists provides insights that icons and symbols emerge tourists’ place attachment to the destination, thereby improving the competitiveness and loyalty of the destination. In this process, it may be fatal to exclude the voices of local residents from the destination image shaping process.

3.2.3. From the Perspective of Suppers

The destination brand literature from the supplier’s perspective focuses on developing sustainable and attractive destination and supplier co-marketing by identifying tourists’ perceptions of the destination. The literature on destination branding from the supplier’s perspective provides two insights: first, suppliers ought to identify which value juncture is crucial for visitors to decide where to visit (associated with Section 3.2.2. From the perspective of tourists (symbols, images and place attachment)) in order to concentrate resources on developing an appealing destination. In this process, attention should be paid to emotional costs (such as perceived risks) over emotional benefits (such as perceived achievements) and social factors; second, destination branding is difficult to be achieved through the efforts of one supplier, and thereby, tourism suppliers are suggested to cooperate to achieve resource sharing, which is conducive to shaping a successful destination brand.

| Perspective | Examples | Studies under This Perspective |

| From DMO perspective (events and activities) | Martín-Santana et al. (2017) [57] reexamined the original case of the “Pink Night” festival from a management perspective, explained how and why DMO explained how and why DMO collaborated with local stakeholders to plan, develop and manage event tourism, and refined meta-events as a brand architecture tool to rebrand and reposition the broader tourism field. | [46,47,57,58] |

| From the perspective of tourists (symbols, images and place attachment) | Jiang et al. (2020) [51] argued that the design of advertisements in tourism destination marketing has the power to arouse cultural derivation and defined the focus of supervision as an intermediary mechanism to further reveal the potential psychological process. | [51,52,53,56] |

| From the perspective of suppers | Khodadadi (2019) [59] explored the challenges faced by Iran’s tourism suppliers in formulating a successful brand strategy for Iran and concluded that tourism suppliers face two main challenges: (1) lack of effort and resources; (2) lack of necessary cooperation between the public and private sector. | [59,60,61] |

3.3. Leading Theme 3: Community and Tourism

In the literature on sustainable destination development, the theme of community and tourism accounts for 10.29% of the total literature and is divided into the (negative) impact of tourism on the community (55.56% of the theme) and suggestions for related solutions (44.44% of the theme).

3.3.1. (Negative) Impact of Tourism on the Community

Tourism has a negative impact on residents’ attitudes towards tourism (27.78% of the theme) and has caused local people to suffer (accounting for 16.67% of the theme). The conclusions of the literature on residents’ attitudes towards tourism are mostly negative; that is, the residents’ negative attitudes towards tourism are found. Tourism has brought sufferings, such as cultural dilution [62] and resource plundering [63], to the locals. The literature on the (negative) impact of tourism on the community provides the following three insights: first, improving resident wellbeing and quality of life can support residents’ hospitality towards tourists, thereby leading to tourists’ satisfaction and repeat tourism; second, the situation between locals and tourists remained tense, and locals forced themselves to be marginalized by keeping silent; third; fortunately, the locals have not shut themselves down completely, meaning that the locals are seeking opportunities from the tourism industry to sustain their livelihoods. Customs have constantly reshaped both continuity and innovation. Therefore, the local people’s voice ought to be fully considered in the development of the destination development strategy so that the indigenous people try to obtain the maximum benefit from the tourism industry and reverse the asymmetric power situation between them and tourists; fourth, for strong religious beliefs in remote island destinations, community isolation may be a way to ease residents’ perception of tourism as “evil”.

3.3.2. Related Suggestions

Regarding the (negative) impact of tourism on the community, scholars have also conducted research on best practices. The main perspective is from stakeholder cooperation (11.11% of the theme); festivals creating community cohesion (5.56% of the theme); residents (residents participate in tourism planning to improve tourism authenticity and their wellbeing) (27.78% of the theme), and tourists (visitors participating in tourism planning) (11.11% of the theme).

First, Stakeholder cooperation is vital in mitigating the negative impact of tourism on the community, among which hegemony among stakeholders needs to be pointed out. All tourism operators share a core system to express hegemony. This hegemony expressed the belief that cooperation should be focused on product portfolios aimed at making products available online and through international travel agencies. Its ultimate goal is to attract more tourists, penetrate the international market, and develop tourism in the region while maintaining corporate income. Communication, trust and the role of the local DMO are also elements of hegemonic representation [64].

Second, the festival not only allows experience sharing, improves communication and networking among diverse and socially excluded groups in the community but also brings stakeholders together to celebrate the cultural community and showcase and share cultural production and practices. In this context, the festival develops shared experiences, practices, and networks within the cultural community and also attracts tourists from the region.

Third, community participation in tourism planning, maintaining the authenticity of the community and improving resident wellbeing has made its support of tourism already regarded as the best practice to alleviate conflicts between communities and tourism.

Fourth, tourists’ participation in tourism planning allows tourists to have a deeper understanding of the meaning of sustainable tourism behavior and increase their respect for community culture.

As such, research to resolve the relationship between communities and tourism provides the following insights: first, residents and indigenous people should be seen as their traditions evolve with modernity and tourism, rather than completely abandoning them. The conceptualization of authenticity by tourists influences how indigenous people choose to represent themselves in tourism; second, in sustainable tourism planning, the voice of residents ought to be fully considered, and the residents ought to be responsible for important management tasks.

| Perspective | Examples | Studies under This Perspective | |

| (Negative) impact of tourism on the community | a. Residents’ negative attitudes towards tourism | Restrepo & Turbay (2015) [65] investigated the silent behavior of the indigenous Kogi people in the Santa Marta area of the Sierra Nevada in front of tourists and argued that silence and indigenous cosmology, which corresponded to the custom of Kogi behavior faced by outsiders and the defense strategy in front of tourists. Silence seems to be a way to isolate oneself while maintaining full contact. | [65,66,67] |

| b. Suffering from tourism to locals | Chong (2020) [62], based on the case analysis of Bali, noted that the suffering caused by tourism to local people includes (1) tourist misconduct is caused by drunkenness and ignorance of local culture and tradition; (2) cultural dilution, for example, some Balinese music, dances, dramas and ceremonies are arranged according to the time of tourists, instead of the original time; (3) the escalation of waste pollution has troubled local people. | [62,63] | |

| Related suggestions | a. Stakeholder cooperation | Based on the theory of social representation, Farsari (2018) [64] investigated the cooperation of Idre, a mountain resort in Sweden, and proposed a cognitive map of tourism participants related to their cooperation. | [63,64,68] |

| b. Festival creates community cohesion | Stevenson (2016) [69] reexamined two annual festivals developed in 2008 outside Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in East London, UK, and discussed the nature of developing social capital through local festivals and their contribution to the social sustainability of emerging destinations. | [69] | |

| c. From the perspective of residents (resident engagement and their wellbeing) | Towner (2016) [70] examined the local community’s participation in surfing tourism in the Mentahua Islands, concluded that the local community regarded foreign ownership and lack of government support as the main obstacles to participation, and then suggested that increasing education and training is the most effective way for communities to participate in tourism. | [64,70,71] | |

| d. From the perspective of tourists (tourist engagement) | Dolnicar (2020) [72] argued that the participation of tourists in designing a more sustainable tourism industry is of environmental importance, rather than targeting the actions of policymakers or staff in the tourism industry. In this light, it is vital to provide visitors with sustainable information (real-time feedback on cultural and environmental damage). | [29,72] | |

3.4. Leading Theme 4: Destination Cooperation

The theme of destination cooperation accounts for 14.29% of the literature on sustainable destination development. The main perspectives are from entrepreneurs (24% of the theme), DMO (24% of the theme), stakeholders (44% of the theme) and travel agencies (8% of the theme). Destination cooperation has a positive role in resource sharing, strategic marketing, service innovation, destination update and evolution, and post-crisis destination image restoration.

3.4.1. From the Perspective of Entrepreneurs (Resource Sharing and Competition)

From the perspective of entrepreneurs, mobilizing and sharing resources allows entrepreneurs to jointly create community-based events, thereby realizing interaction between enterprises and residents and improving social inclusion and cohesion [65,73], but there are also situations of resource competition and unequal access to resources among entrepreneurs. The entrepreneur’s perspective on the destination resource sharing and contention literature draws the following insights: first, entrepreneurs are capable of improving social inclusion and cohesion through resource sharing; second, the conflict between actors who integrate society into the local community and external entrepreneurs will continue to exist, and the results will exacerbate local differences and hinder cooperation with entrepreneurs; third, informal entrepreneurs play a crucial role in sustainable destination development because they are more flexible than formal entrepreneurs, resulting in that they can quickly adapt to changing market changes and reposition and that they have the ability to quickly combine culture, symbolism, and social capital, thereby providing an important asset to the tourism stakeholder. However, the capacity of informal entrepreneurs has been underestimated in academic debates and actions by governments and NGOs.

3.4.2. DMO (Strategic Marketing)

DMO, as the vital actor in sustainable destination development, is a complex network, encountering huge challenges. The DMO perspective draws the following insights into the strategic marketing literature: first, the challenges of DMO strategic marketing often include managing growth while maintaining a sense of location, managing multiple objectives, limited funding and limited capacity for marketing and development. Therefore, DMO should develop a destination strategic management culture to meet the challenges of strategic marketing, thereby achieving network connections between stakeholders; second, the limitations of policy-led DMO limit the development of product services, and the DMO resource allocation function is restricted, which may eventually have a ripple effect on the entire industry, resulting in a chaotic network.

3.4.3. Stakeholder Perspective (Service Innovation, Destination Update, Crisis Management and Cross-Border Cooperation)

Stakeholder cooperation plays a key role in service innovation, a destination update, cross-border cooperation and crisis management [74]. The stakeholder perspective draws the following insights on destination cooperation: first, at the EU level, the sustainability of destination development depends on the cooperation of neighboring countries, which is why cross-border cooperation is used as an important tool for promoting and advancing the principle of sustainability throughout the EU; second, the cooperation of stakeholders plays an important role in value innovation, shaping the image of the destination and enhancing the competitiveness of the destination, during, which, the voice of the residents ought to be highly considered.

3.4.4. Travel Agency

The role of travel agencies in destination coordination is often overlooked. In fact, they are capable of improving distribution channels, accelerate the speed of entering new markets, and gain new market opportunities.

| Perspective | Examples | Studies under This Perspective |

| From the perspective of entrepreneurs (resource sharing and competition) | Cristofaro, Leoni and Baiocco, (2020) [75] refined the co-evolution of the company level and the destination environment, arguing that the sustainable development of tourism destinations is the result of the co-evolution of the tourism company and its environment.Buckley et al. (2017) [76] discussed the competition for new and precious tourism resources in the Maldives surfing purpose based on the property rights framework and concluded that the struggle for control over the upstart natural resources is carried out through politics rather than pure administrative procedures. | [67,73,75,77] |

| DMO (Strategic Marketing) | McCamley and Gilmore (2018) [67] emphasized the importance of strategic marketing plans for each function by investigating the strategic marketing planning process of heritage tourism and considered the role of DMO from the perspective of providing strategic directions. | [78,79,80] |

| Stakeholder perspective (service innovation, destination update, crisis management and cross-border cooperation) | Moscardo (2020) [81] discussed how innovative opportunities could transform archaeological heritage into valuable creative tourism resources through cooperative innovation and concluded participants that are not traditionally related (such as construction developers and cultural tourism enterprises) the cooperation between the local tourism or heritage authorities may be needed to jointly innovate the destination. | [43,74,81,82,83,84] |

| Travel agency | Frenzel (2017) [85] argued that travel agencies are able to alleviate the power of tourists in shaping destinations against the intentions of local elites and established tour operators by increasing tourists’ valuation of destinations, thereby contributing to the sustainability of the purpose. Abou-Shouk (2018) [86] emphasized the coordinated role of tourism agencies in promoting DMO network collaboration. | [85,86] |

3.5. Leading Theme 5: Destination Governance

Destination governance accounts for 5.71% of the sustainable destination development literature. The main perspectives are political environment governance (40% of the theme), cross-border governance (30% of the theme) and public–private partnership governance (30% of the theme).

3.5.1. Political Environment Governance

Political and economic stability, legal services, and functional local authorities are the foundations for achieving sustainability in the destination. The political environment governance literature illustrates the following insights: first, the destination governance system needs to be modified to effectively formulate and implement tourism policies based on the coordination and cooperation of all stakeholders; second, in order to ensure a higher level of coordination in the tourism industry itself, governance must overcome barriers to incoherent industries that cannot adequately represent vulnerable interest groups, because these interest groups are usually composed of local community residents.

3.5.2. Cross-Border Governance

The path dependence of cross-border governance has led to the complexity of its projects, including (a) incorporating tourism into a larger multilevel governance structure in border areas; and (b) following the multiscale and comprehensive characteristics of tourism, tourism governance and planning are politicized and full of power. Therefore, understanding the destination governance process in border areas requires: (i) a clear multiscale analysis; (ii) recognition of cross-border and intra-national conditions; (iii) more pollination between tourism planning and cross-border governance research. The cross-border cooperation governance literature draws insights that cross-border cooperation should fully consider the characteristics of its path dependence because this leads to the complexity of these cross-border projects.

3.5.3. Public–Private Partnership Governance

The literature on public–private partnership governance provides the following insights: first, DMOs and related institutions play an important role in simplifying processes for the success of public–private governance and can use digitally supported platforms to achieve continuous interaction; second, as new entrepreneurs and companies are entering community-oriented destinations, this requires new stakeholders to participate in the current system, which is strongly determined by social bonds and embedding.

| Perspective | Examples | Studies under This Perspective |

| Political environment governance | Syssner and Hjerpe (2018) [87] investigated the government’s governance in Swedish tourism development and concluded that DMP hopes that local governments will be able to institutionalize destinations, promote cluster planning, incorporate destination development into the strategic planning process, and ensure that relevant knowledge is provided and developed. | [87,88,89] |

| Cross-border governance | Müller et al. (2019) [90] argued through a case study of cross-border tourism in Siberia that government interests are imbalanced and the private sector (large state-owned enterprises and microentrepreneurs) diverges, making it difficult to establish a stable governance model. To some extent, knowledge institutions that are less integrated into government agencies can act as organizers of triple helix cooperation at different levels (from regional systems to specific key events), but such initiatives still depend on the state/region funding and political priorities. Cross-border governance is a common feature of the Alps (e.g., Valtellina) and Scandinavia (e.g., Lapland), where existing public organizations, private actors and community networks have proven “African growth and innovation have a positive impact”. | [90] |

| Public–private partnership governance | Bichler and Lösch (2019) [91] identified the drivers and barriers to collaborative governance in community-oriented destinations in South Tyrol (Italy). At the destination level, leadership is the main driver of collaborative governance, which supports trust and communication between entrepreneurs and representatives of public institutions. | [91,92] |

3.6. Leading Theme 6: Digitalization

Digitalization, along with information and communication technology (Hereinafter referred to as ICT) and other smart technologies, is an emerging theme that provides insights for sustainable destination development, which account for 10.86% of sustainable destination development literature. ICT brings wisdom into organizations and communities, thereby contributing to more competitive tourist destinations (i.e., smart tourist destinations). The main perspectives are social networks (42.11% of the theme) and smart destinations (57.89% of the theme).

3.6.1. Social Media

Social media allow managers to analyze visitor behavior and the best destination promotion time based on big data, while the word-of-mouth communication achieved by online reviews on social media has a causal relationship with destination brands and tourists regarding the sustainability of destinations and their environmentally responsible behavior. Electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) is considered to be credible and more authentic than the media or destination promotion’s effect on tourists’ perception of the destination’s sustainable image because the source may be considered a non-commercial source [93]. Revisiting intentions and active word-of-mouth communication are significantly affected by the three dimensions of sustainability.

3.6.2. Smart Tourism

The overall goal of smart tourism is to provide an interface between tourists and destinations to respond to specific needs in a targeted manner. The sensible tourism destination is characterized by the use of advanced technology and interfaces for high innovation and convenience. In particular, these destinations use “advanced technology and open, multipolar, integrated and shared processes” to improve the quality of life of residents and tourists. Resource optimization is an indispensable part of the function of the smart tourism destination system, which links this concept with sustainability.

The proliferation of digitization in the sustainable destination development literature has guided the following insights: first, although ICT brings wisdom into organizations and communities and thus contributes to smart tourism destinations, one problem with smart tourism is technological dependence, which is important for people with or without smart devices. Moreover, the establishment of a broad digital divide between destinations that can or cannot afford smart tourism infrastructure has a major impact. In this sense, smart tourism infrastructure will lead to new information imbalances. Therefore, the smart tourism environment must consider use-value, that is, create value by using data and/or technology rather than possessing data and/or technology; second, researchers and destination managers should seek to develop and monitor ICT, linking the travel experience design of tourists to the wellbeing of residents; third, it should be noted that tourists may pay more attention to the value they perceive from the travel experience of the destination, rather than perceiving value and wellbeing from those smart travel technology.

| Perspective | Examples | Studies under This Perspective |

| Social media | Villamediana et al. (2019) [94] investigated the impact of time range (post date and time) and seasonality (low, medium and high) on active/negative participation in the destination management organization (DMO) on Facebook. They concluded that the best time to post on media is 8 o’clock, 10 o’clock, 2 o’clock and 5 o’clock, while Thursday and Saturday are the best days to post, and the period before summer (from January to June) is the best month. These results provide guidance for DMO and the National Tourism Organization (NTO).Koo (2018) [95] investigated the causality between international tourists’ sustainability and environmentally responsible behavior of Jeju Island, South Korea, revisits intentions and active word-of-mouth communication, and concluded that environmentally responsible behavior is positively affected by cultural sustainability and is negatively affected by environmental sustainability. | [36,93,94,95,96,97,98] |

| Smart tourism | Cornejo and Malcolm (2020) [99] examined the views of different tourism experts in Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, on smart tourism destinations and concluded that there are at least three determinants that determine the implementation of smart tourism destinations: training, investment, and governance.Williams et al. (2020) [93] criticized the concept of smart destination, emphasizing that (1) smart destinations are driven by uncertainty; (2) knowledge provides deeper insight than information, making information an innovative smart destination; (3) entrepreneurs play an important role in promoting smart destinations; (4) smart destinations constitute an innovative system. | [37,93,99,100] |

4. Statistical Analysis Results

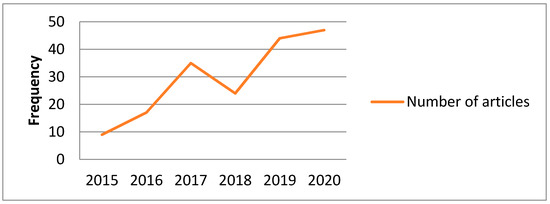

4.1. Distribution by Publication Year

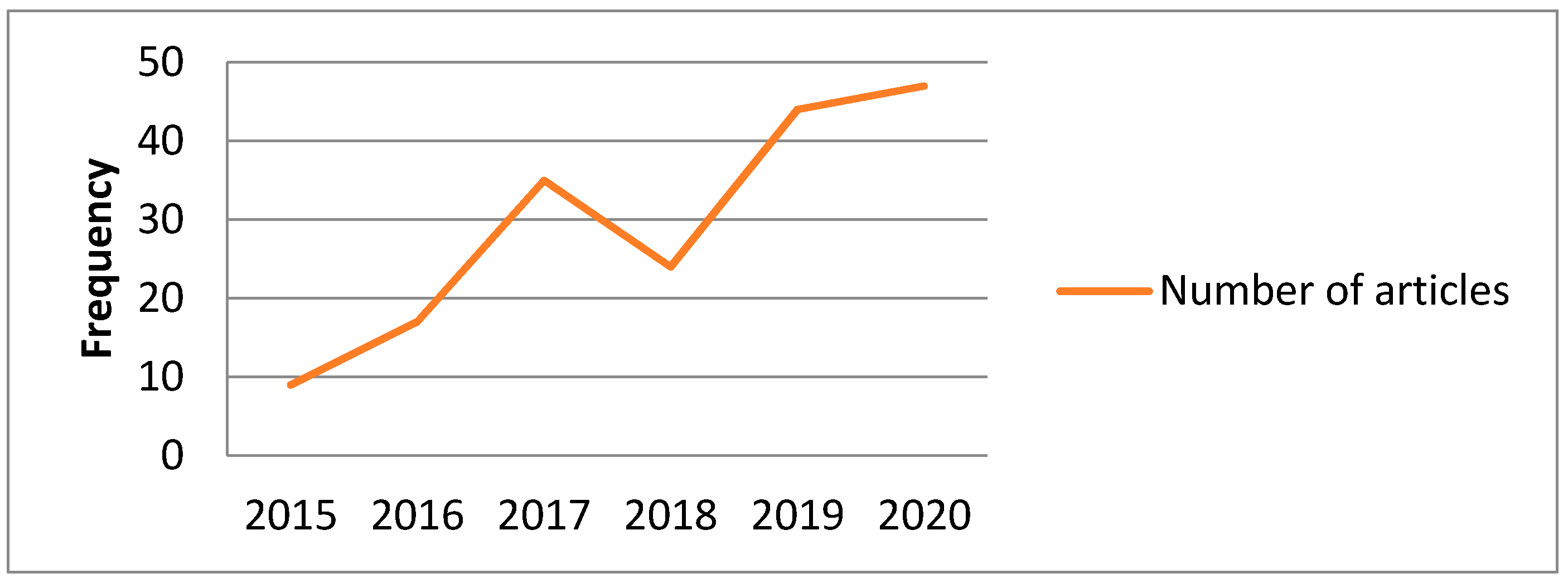

Figure 2 gives valuable information regarding the frequency distribution by publication year. From 2015 to 2017, there has been considerable growth in the number of articles published on sustainable destination development. From 2017 to 2018, the number of publications has decreased, while in 2018–2020, the number of publications climbed to its peak in 2020.

Figure 2.

Distribution by publication year.

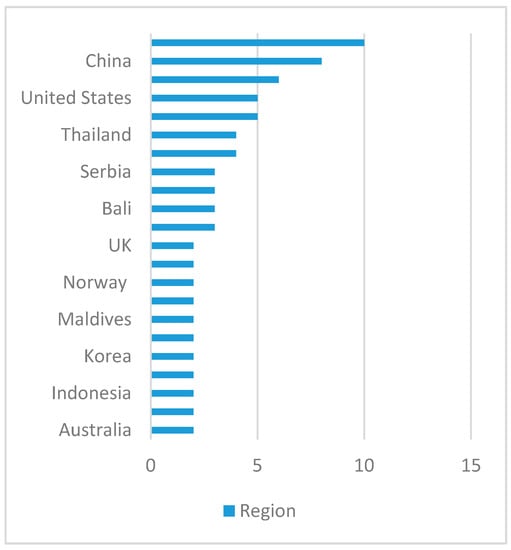

4.2. Distribution by Regions

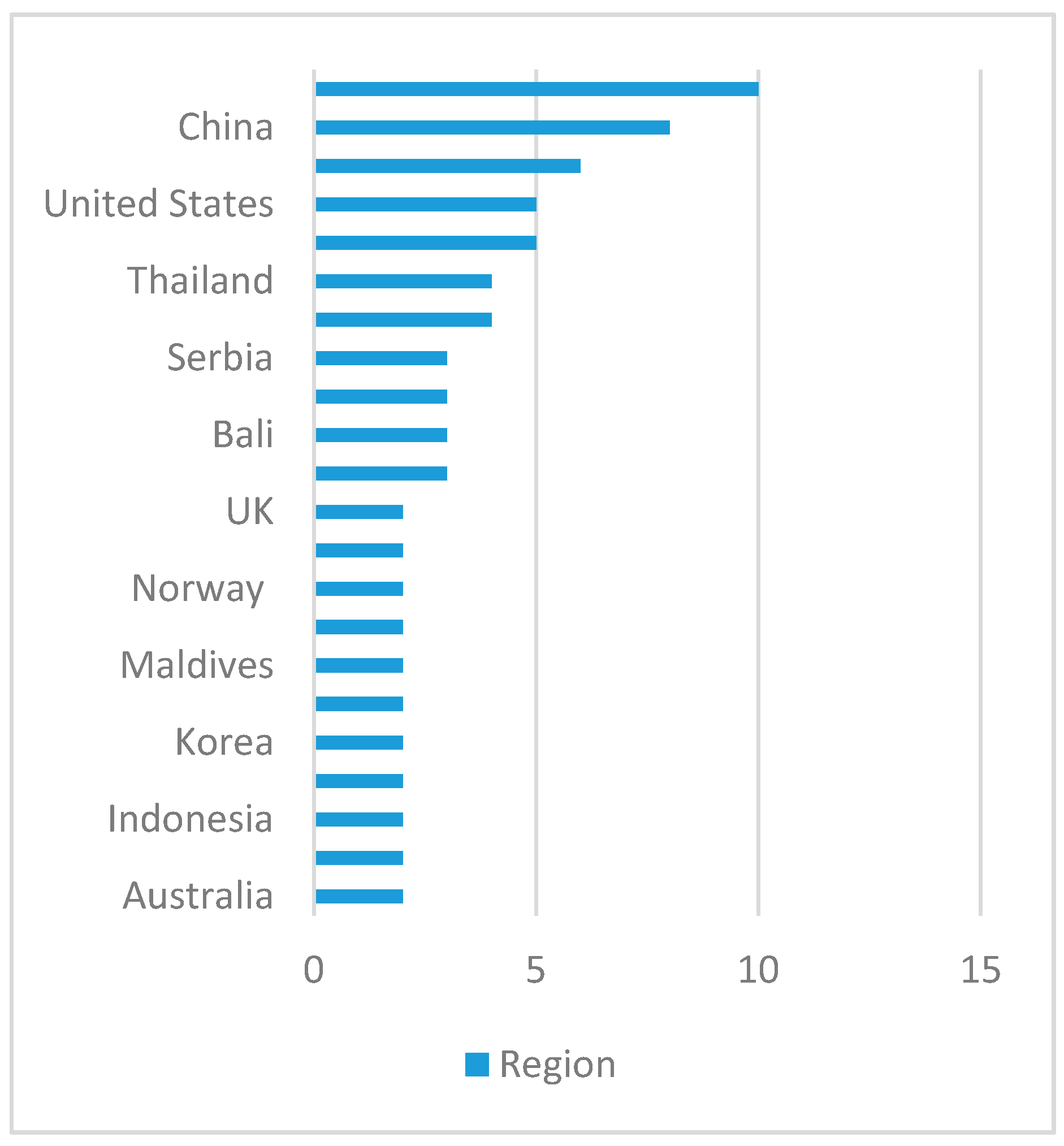

Figure 3 gives valuable information regarding the frequency distribution by region. The region here refers to the region studied by the author in the article, not the country from which the author came. Excluding those studies that do not have a special region, all regions that have been studied more than once are counted. Spain is the most studied country, followed by China, the United States and India. Since cross-regions are involved as one of the main perspectives, mixed regions are also repeat studied.

Figure 3.

Distribution by regions.

4.3. Distribution by Methodology

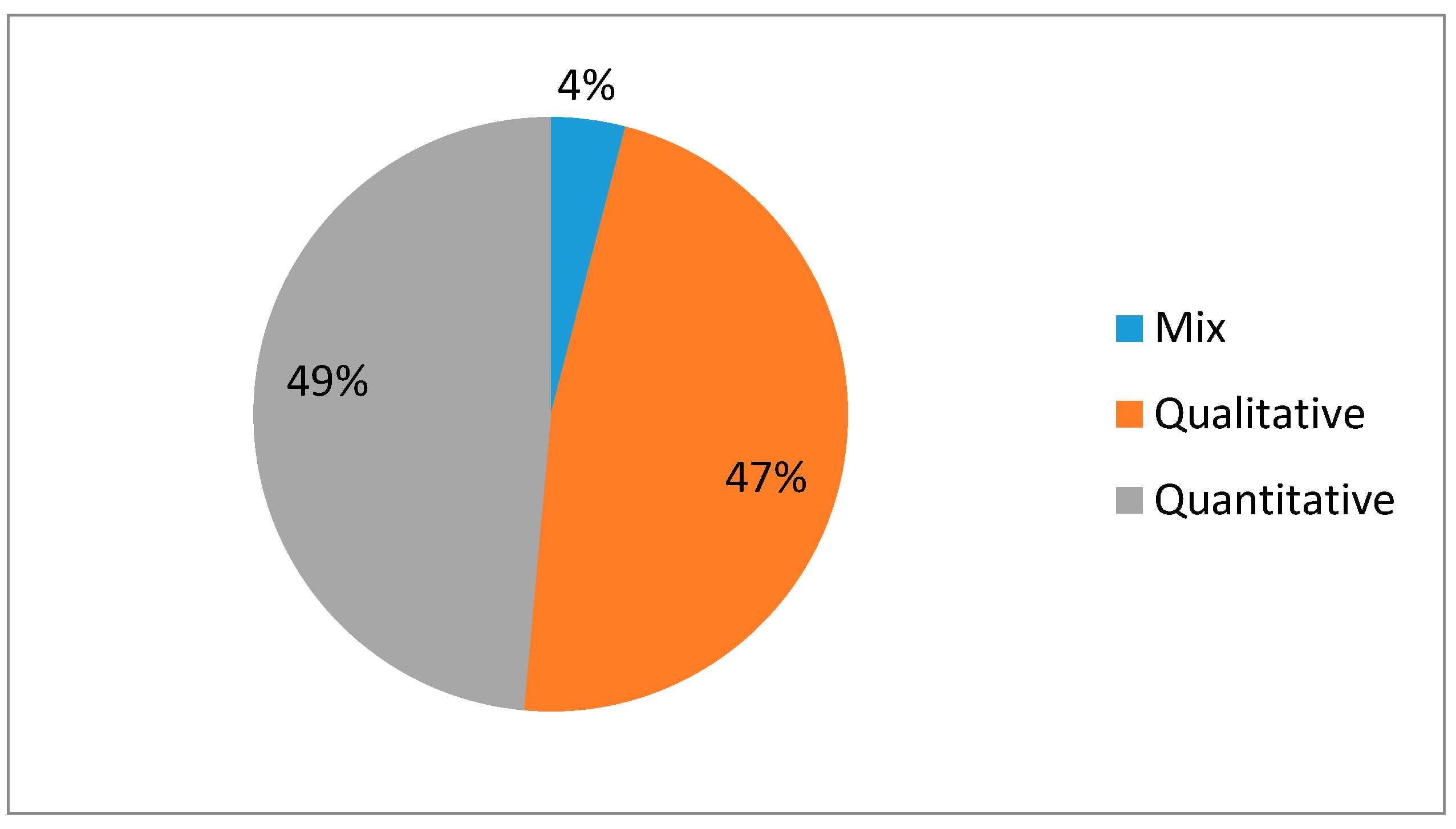

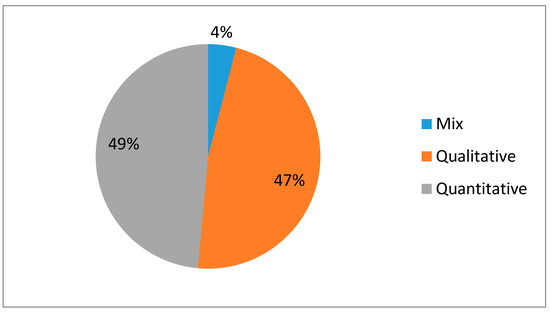

Figure 4 gives valuable information regarding the frequency distribution by methodology. Quantitative methods are slightly more than qualitative methods. It is worth noting that 24.39% of qualitative research is a method of literature review, that is, answering research questions by browsing past literature. Moreover, the Delphi method, case study and fieldwork method are also widely used in qualitative research.

Figure 4.

Distribution by methodology.

4.4. Distribution by Theory

Given the interdisciplinary nature of sustainable destination development, diverse theories have been adopted. In the literature of sustainable destination development, the theory that is used repeatedly reflects the popularity of the applied perspective or the classicity of the theory. First, semiotic theory is repeatedly used to study the perspective of tourists (symbols, images, and location attachment). Since the creation of destination symbols can stimulate tourists’ images of destinations, it is conducive to the influence of destination brands and ultimately produces location attachment and destination loyalty. Location attachment, destination image and destination loyalty theory are linked to semiotics.

Oliver’s (1993) [101] cognitive decision-making model is repeatedly applied to the analysis of tourists’ psychology and decision-making. Self-determination theory (SDT) is related to science and is repeatedly applied to tourists’ perception of destination tourism. Social network analysis (SNA) is repeatedly used to analyze destination stakeholder cooperation.

Due to its classicity, Butler’s (2006) [102] tourism area life cycle (TALC) theory has been the most repeated theory, which is used to analyze the impact of destinations on residents, destination images and destination transformation and update. Likewise, Bourdieu’s regions and capitals theory, the theoretical framework of practical theory and symbolic interactionism theory are adopted to analyze capital exchange among stakeholders, resource sharing and competition among entrepreneurs and stakeholders Cooperation. Ethnography is repeatedly applied to the study of spiritual tourism, Arctic tourism and indigenous tourism, thereby supporting the tourism industry from the perspective of residents, emphasizing the preservation of the authenticity of the community.

To conclude, Table 3 summarizes the leading sustainable destination development themes and perspectives and their proportions.

Table 3.

Leading sustainable destination development themes and perspectives and their proportion.

5. Discussion

5.1. Attention Shifted from Government to Tourists, Triggering Exploration of Diverse Disciplines in Sustainable Destination Development

After defining leading themes and perspectives on sustainable destination development, we took an immanent critique method to discuss our findings. The immanent critique method means that we will discuss the limitations of the ideological system based on the internal assumptions of sustainable development. The contradiction points out can be “theory-theory, theory-practice and/or theory-data inconsistency” [8]. Once gaps in specific ways of thinking or acting have been identified, we can use more focused resources and energy to overcome these deficiencies [8], thereby narrowing the gap between theory and practice.

At a glance at the six leading themes we defined, it is clear that the percentages of the top five themes are not much different, ranging from 10.29% to 17.14%, and, more important, they are all about people. Kant systematically discussed the four most important questions in his criticism: What is a person? What should one know? What should one do? What should one wish for? It is interesting to bring these four questions into the field of sustainable destination development. Who are the key stakeholders in sustainable destination development? What should they know? What should they do? Moreover, what should they wish for?

This study gives a firmer answer to the first question, that is, the sustainable destination development literature in the past five years indicated that the five important stakeholders are tourists, DMOs, community residents (including indigenous), entrepreneurs (Including travel agency), government. Their importance is reflected in their frequency in the literature over the past five years. These “persons” are a collective term composed of a large number of “persons” with a common purpose and characteristics, representing a group or type of stakeholders. These groups have internal contradictions. A huge contradiction seemed to shake one stakeholder, the government, which had the most hegemony in the beginning. A noteworthy finding is that destination governance ranked as the sixth leading theme in the sustainable destination development literature over the past five years, with only 5.71% of the total.

“Power” has been considered at the core of the sustainable development debate for the past 20 years, and its fundamental explanation is structural change [103]. The concept of governance is a natural fit with the sustainable development debate [8]. It was originally designed as a goal-oriented activity to intentionally adjust knowledge practice, but people gradually realized that sustainable development is not an ultimate state but a dynamic social process [7]. No matter when it is, whether it is within or between countries, there is a party that dominates knowledge, wealth, power, and discourse, choosing to focus on GDP indicators. These institutions undermine the ability of sustainable development to act as a tool of transformative politics by avoiding some of the root causes associated with sustainable development, and by never addressing the underlying problems that underpin poverty, they place the concept of sustainability in the hegemony of the unilinear mainstream ([104,105,106]). In contrast, the disadvantaged, who represent poverty, are highly concerned about the happiness and democratic participation [107]. Many scholars generally refer to the two sides as the North and the South. The voices of the weak side respond to a view of sustainable development as a social crisis and one of human behavior, rather than a growing “ecological civilization” based on environmental discourse [108].

However, globalization and media have brought together the voices of the world’s disadvantaged, leading to a two-way flow of power from the top to the new global center and from the bottom to the specialized nodes of global governance [109], thus destabilizing regionalism and hegemony [110]. From Foucault’s perspective, power itself promotes leadership and the vision of liberation from the lower levels, but it cannot provide vision or leadership because power should come from the lower levels. The vacillation of localism and hegemony has made the increasing power of non-state actors and civil society new rationality for government coordination and governance [111]. Polycentricity and neoliberalism are a double-edged sword in sustainable tourism. Due to the market-oriented tourism industry, neoliberalism encourages entrepreneurial innovation and the diversification of products and services. However, is the decentralization of power necessarily good? From the socio-political point of view, as the government loses control over the flow of more and more commodities, wealth, raw materials, talents, culture, pollution and ideologies in tourist destinations, a new scope of power is generated across borders [8]. These power domains adopt different ways, such as multilevel governance, multicenter governance, network governance, mixed collaboration, etc., which may hinder the effectiveness of tourism destination governance [112]. These “new” governance structures that are changing are constructed of jurisdictions and regimes that belong to different disciplines and try to create a structure for the “new” governance that the world is witnessing [8]. Thus, the theme of destination governance can be seen as a starting point, which held hegemony in the early days of tourism and sustainable tourism literature development, but has gradually evolved over the past five years into a multilevel governance concept of sustainable development, providing a foundation and coherent understanding for a new discourse on sustainable destination development. We still cannot say that decentralization of power and bottom-up governance of tourist destinations are necessarily good, but it certainly has led to exploration from multiple disciplinary perspectives, such as political science, political ecology, geography, even inflexible thinking and complex system under the background of the theory of ecology [8].

The role of tourists as recipients and assessors of tourism products and services is most relevant to sustainable destination development in the last five years of the study. Tourist satisfaction is the most leading perspective. Tourists increase satisfaction from a variety of tourism products and services, both mentally and physically, which determines whether repeat tourism and loyalty to the destination is generated. Tourists pay increasing attention to the effect of tourist destinations on their spiritual recovery during their travels. Therefore, the development of spiritual tourism has a positive effect on sustainable destination development if the local culture, people and resources are properly combined. It will help visitors discover spiritual self-awareness and stimulate their desire to protect the environment so as to bring special value to nature. Due to the relationship between tourist satisfaction and destination attachment, semiotics and place attachment have been widely used in the research of destination branding in the past five years. The destination image and symbols can stimulate the image perceived by tourists, thus generating their place attachment, and eventually lead to their loyalty to the destination and repeat tourism.

Entrepreneurs act as direct providers of tourist satisfaction. Entrepreneurs compete among themselves due to limited resources, but they also realize the importance of win–win cooperation. This is manifested by entrepreneurs working with each other and with DMOs and communities to promote destinations and host tourism events, as they increasingly realize that to gain personal benefits, they first need to work with others to attract visitors to the destination.

Another obvious trend is that tourists are the recipients and evaluators of tourism services and are encouraged to act as providers of tourism, which is related to tourism ethics. The negative impact of tourism on communities has been a perennial theme for 20 years, which revolves around the disaster of tourism to marginalized people in communities (women, the elderly, indigenous people, etc.). However, the literature of the past five years has shown that tourism and community development are not incompatible, even though the literature on residents’ attitudes towards tourism has drawn mostly negative conclusions. Tourism has brought sustainable development issues to the locals. However, one trend is that local people (including aboriginal people) have not completely shut themselves off in the wave of tourism development. The customs are constantly being reshaped, and aboriginal modernity emerges. This trend can be a positive or negative cycle. A promising and positive cycle is that the government, DMO and entrepreneurs work together to provide community-based and nature-based tourism activities for tourists and provide tourist education at all tourism stages (before the tourist arrives at the destination, while traveling, and after leaving the destination). This approach allows tourists to (1) understand what they should and should not do before they arrive at the destination, (2) appropriately interact with local residents and learn about ecology and culture when traveling, (3) actively spread the ecological and cultural knowledge of the destination as an ambassador after leaving the destination. A sustainable tourist behavior will greatly ease the residents’ rejection of tourists, and a hospitable community will, in turn, increase the satisfaction of tourists and maximize the chance of tourists returning to their destinations. Tourist participation in tourism planning enables tourists to have a deeper understanding of sustainable tourism behavior and increases their respect for community culture. One exception is that for remote island destinations with strong religious beliefs, community isolation may be a way to alleviate residents’ perception of tourism as “evil”. Tourists are encouraged to act as designers and providers of tourism, and this trend will promote this promising and positive cycle.

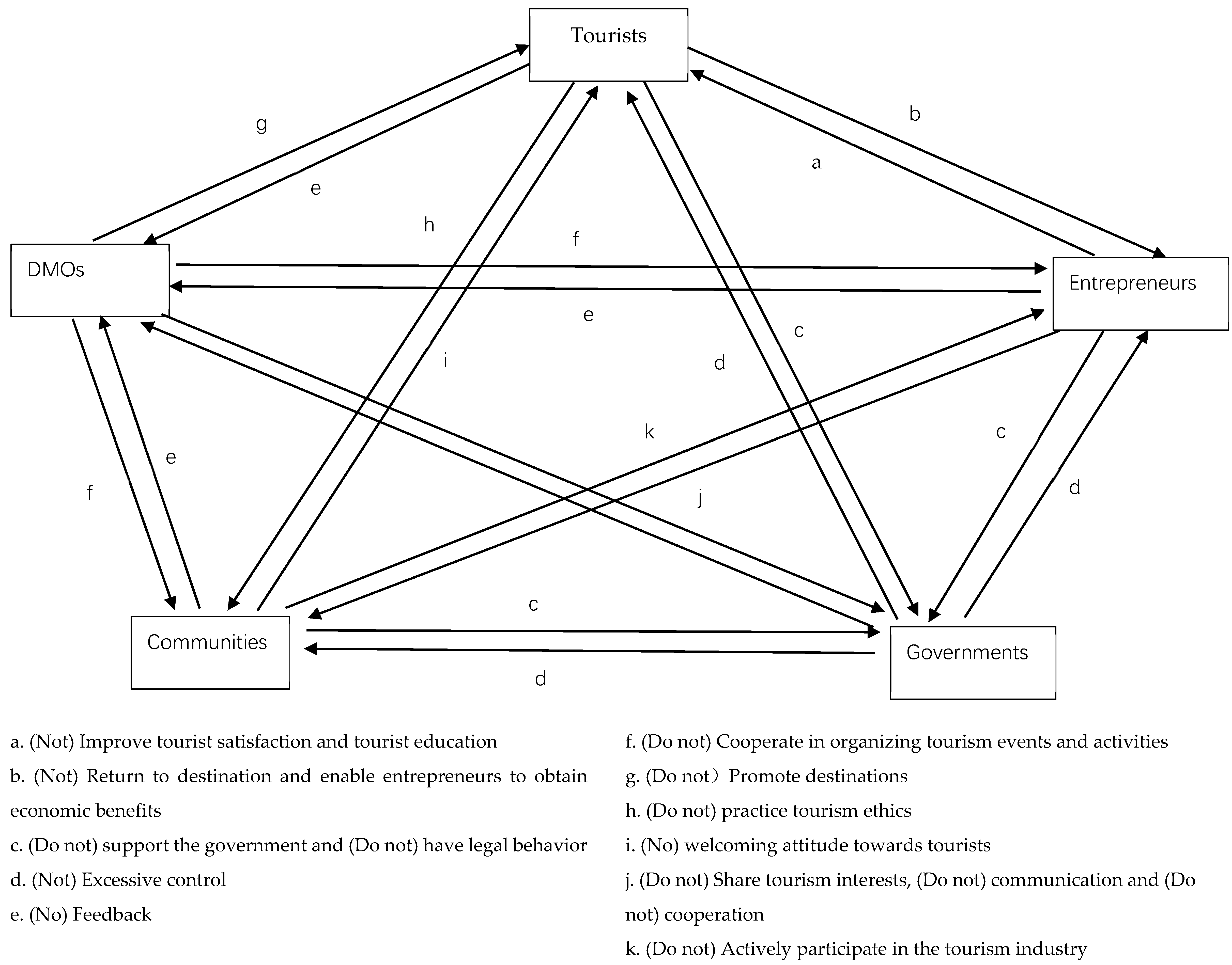

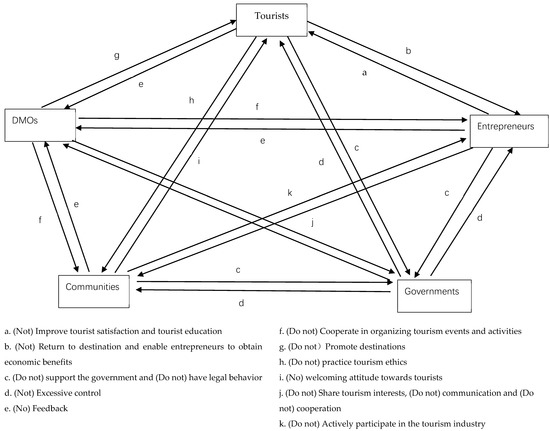

5.2. Consensus Rather Than Definition, Balance Rather Than Choice

In Figure 5, we have mapped the interrelationships of these five stakeholders. These internal relationships are reflected in the leading perspective that was identified. The five main destination stakeholders can have conflicting relationships. For example, tourists may have a hostile relationship with the residents of the community, resulting in the community not welcoming tourists and reducing tourist satisfaction; The government may exercise excessive policy control over enterprises in the tourism industry, causing entrepreneurs to resist the government through illegal operations. This confrontational and conflicting relationship may lead to a negative cycle, damaging the interests of every stakeholder in the long run. On the contrary, they can also be mutually reinforcing relationships, as mentioned above, through communication, understanding, competition and cooperation. This relationship of mutual understanding, mutual tolerance and mutual promotion may lead to a positive cycle that will benefit every stakeholder in the long run. We prefer and do call the latter sustainable destination development, as shown in Figure 5. Because of the ambiguity of the word “sustainability”, we do not yet know whether “sustainability” is really good for the environment, communities and the economy in the long run. However, in this review of the literature on sustainable destination development over the past five years, we do see a trend that indicates “what people should do” and “what people should not do”.

Figure 5.

The internal relationships among the 5 main stakeholders of destination development.

The obsession with “definitions” is harmful because it diverts attention from the underlying and unresolved issues. These sustainable problems require a common, integrated framework for changing human behavior [108]. For example, the discourse of sustainability emerged in the context of climate change, a series of financial and political crises, and global neoliberal hegemony discourse [113]. The endless debate over definitions can mask problems, such as government reluctance to promote significant fiscal or financial reforms [113]. Sustainable tourism development itself is dynamic and self-development. It does require a large number of institutional changes, but these changes do not necessarily need to be driven by artificially discussed sustainable agendas ([114,115]). This means that sustainable destination development needs a consensus rather than a definition [8] because sustainable destination development has been called part of historical development along with economic and social structures. It requires a competitive paradigm to break the paradigm of linear models of growth and accumulation [8], but it also requires a greater tolerance because sustainable destination development requires a compromise of economic growth and power, fundamental support and protection for the disadvantaged, and equity.

5.3. Does the Defined Trend Indicate That We Have Found a Correct New Paradigm for Sustainable Destination Development?

Research on sustainable destination development, due to its complexity and interdisciplinarity, should be reviewed over time to prevent duplication of efforts. It is a timeless topic, one that is hard to define but has important implications for the reality of what kind of debate scholars should continue to have. A common view is that sustainable destination development is a slow, gradual process that requires the joint efforts of scholars in various disciplines and knowledge exchange and integration to build a comprehensive framework. Interdisciplinary research is well suited to address the complexity of sustainable destination development in order to properly address the subject. Newell (2001) [116] and Boix (2006) [117] argue that without such an approach, there is no solution. Reference and integration of different points of view to the interrelation between the different aspects of this complex phenomenon and dynamic thoroughly explore [116], from more elements (such as knowledge, ideas, methods or disciplines) begin to consolidate and then reflect on and form new elements, such as the new knowledge, new ideas, new methods or new subject. As a result, new disciplines are constantly emerging, and it seems more meaningful to discover neglected fields than to list which ones are covered.

The inherent contradictions and inclusiveness of sustainable destination development give rise to a variety of possibilities in its disciplines: politics, political ecology, geography, and even ecology in the context of elastic thinking and complex systems theory. The ever-changing dynamic configuration has spawned new disciplines and approaches that respond to the meaningful integration of tourism destination stakeholders and sustainability [8]. By conducting a content-based literature review of the sustainable destination development literature over the last five years, we have identified six leading themes and perspectives that indicate an interdisciplinary character and trend, but does this trend indicate that we have found the right new paradigm for sustainable destination development? Not really. One of the reasons for this is that in our research, an important stakeholder, who speaks for something that is not a person-a destination, an environment, a plant, an ecosystem, is missing-NGOs. The role of NGOs in sustainable tourism has not been mentioned much in the sustainable destination development literature over the past five years. However, as an important stakeholder, NGOs play a role in monitoring, encouraging and promoting the dissemination of knowledge and providing tourism development opportunities. Therefore, we strongly urge future research to actively explore the role of NGOs in sustainable destination development.

6. Conclusions

This study analyzes the literature on sustainable destination development over the past five years by using an exploratory and descriptive approach, with the aim of providing evidence and indications for its interdisciplinary character. As a result, we defined six leading themes and perspectives.

Why is sustainable destination development interdisciplinary? Because it involves multiple stakeholders, they are mutually inclusive and conflict. This is in line with the “people-centered” focus of sustainable destination development. As sustainable destination development requires the exchange and integration of disciplines, new disciplines are constantly emerging. It is valuable and necessary to review past research results in order to avoid unnecessary and repetitive efforts and to identify areas that have been overlooked.

How should we evaluate and use the results of past academic research? First, scholars need to recognize the interdisciplinary and dynamic nature of sustainable destination development to address uncertainty and complexity issues. Adaptive knowledge management tools should be used to align goals and actions so that scholars can adapt to change. Second, stakeholders in the tourism industry should not only be regarded as research objects, but they should also be encouraged to participate in the research process. On one hand, this can promote research progress through knowledge sharing and collaboration, and on the other hand, it also provides a channel for stakeholders to learn. Third, this study discovers the shift in focus from government to tourists through a review of past studies and the emergence of digitalization as an emerging discipline, indicating that it is worthwhile to review research on sustainable destination development at regular intervals to avoid duplicative efforts and to discover emerging and neglected areas.

The leading theme and perspectives defined point out some important but overlooked areas. We know what sustainable destination development is, so how do we define an unsustainable destination? Concerning the recent frequent man-made and natural disasters, whether and how tourism affects the psychology of the residents of the affected destinations? As for the new digital natives, how can we educate millennials about their values so they can travel more sustainably? Smart destinations are beginning to be introduced in developed mass tourism destinations around the world. How can smart destinations improve the participation and happiness of residents and tourists? Social media has made communication between stakeholders in the tourism industry transparent. How should we use it to have a positive impact on sustainable destination development? Tourism is not just an activity for adults. Teenagers and children also gradually influence their destinations along with their parents and schools. This is related to family holiday destination decisions and sustainable consumption. Then what kind of destination suits them? In addition, future research may focus on how to transform the ideas, models and principles of sustainable destination development into events. In short, the challenges of sustainable destination development are irreversible. How to overcome and mitigate these challenges requires solid empirical research involving various stakeholders, among which residents and marginalized groups should be given priority.

Finally, we need to point out the limitations of this study. Keyword searches of crucial journals in major databases can greatly reduce my subjectivity in defining trends. First, it is worth considering other theme classification ways to find out other leading perspectives and themes. For example, the crisis management theme can be classified into the perspective of tourists, the perspective of government governance, and the perspective of destination cooperation to enhance the image of crisis destinations. Likewise, it is worthwhile to separately classify the theme of Arctic tourism to identify different angles in this theme; second, the statistical results of the proposition only reflect the direct correlation between the literature and the theme or perspective. Since sustainable destination development is an interdisciplinary field, other mixing perspectives and trends may also be included in the literature; third, this research only reviewed articles, and thus others, such as book chapters, annual reports, and comments, may portray a broader picture. It should be noted that we searched in the online databases of only four publishers. In the methodology section, we explained the reasons for choosing this method instead of other broader search engines, such as Web of Science, Scopus, Google Scholar. Although this method improves the quality of the included publications to a certain extent, it limits the scope of the search and may not include some references that are also valuable. Therefore, we encourage expanding the search scope smartly in future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.P.-F. and S.L.; methodology, U.P.-F. and S.L.; resources, U.P.-F. and S.L.; data curation, U.P.-F. and S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, S.L.; writing—review and editing, U.P.-F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Saarinen, J. Critical sustainability: Setting the limits to growth and responsibility in tourism. Sustainability 2013, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Our Common Future; Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- World Tourism Organization. Guide for Local Authorities on Developing Sustainable Tourism, 2nd ed.; World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), Ed.; TSO: Norwich, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, C.M. Policy learning and policy failure in sustainable tourism governance: From first- and second-order to third-order change? J. Sustain. Tour. 2011, 19, 649–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, T.; Becker, E. (Eds.) Sustainability and the Social Sciences: A Cross-Disciplinary Approach to Integrating Environmental Considerations into Theoretical Reorientation; Zed Books: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. The Archaeology of Knowledge; Tavistock Routledge: London, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Redclift, M.R. Wasted: Counting the Costs of Global Consumption; Earthscan: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Boda, C.; Faran, T. Paradigm found? Immanent critique to tackle interdisciplinarity and normativity in science for sustainable development. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyle, B.D.; McLennan, C.-L.J.; Ruhanen, L.; Weiler, B. Tracki+ng the concept of sustainability in Australian tourism policy and planning documents. J. Sustain. Tour. 2014, 22, 1037–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kates, R.W. What kind of a science is sustainability science? Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 19449–19450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, I. Social Sustainability and Whole Development: Exploring the Dimensions of Sustainable Development; Zed Books: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rendtorff, J.D. The ethics of integrity: A new foundation of sustainable wholeness. In Philosophy of Management and Sustainability: Rethinking Business Ethics and Social Responsibility in Sustainable Development; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2019; pp. 161–170. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.M. Global Environmental Issues; Smith, D.P., Warr, K., Eds.; Hodder Arnold H&S: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]