Abstract

The agenda for an engaged and impactful archaeology has been set out emphatically in a variety of recent reports, positioning archaeology and heritage as important sources of public value and social benefit. While many ascribe to these aims, how to put them into practice in concrete terms remains a real challenge. Tools, methods and methodologies developed for the wider research community as it engages with the “impact agenda” at large have been adapted and applied in archaeological and heritage practice with variable success. In this paper, we discuss the creation of a values-led, card-based design toolkit and the considerations involved in customising it for use by archaeology and heritage sector practitioners. We evaluate reflexive feedback from participants in a toolkit testing workshop, together with our own reflections on the workshop experience. Building on these, we assess the potential and limitations of the toolkit and its underpinning values-led design theory to generate critically engaged archaeological and heritage experiences.

1. Introduction

1.1. This Work

Heritage, in all its diverse expressions, is made up of our selective memories of past communities’ ways of living (for selected alternative definitions of this slippery term see [1,2,3]). Archaeology, generally described as “the study of material remains or traces of human activity,” [4] (p. 853) is an active component in many expressions of heritage. Practitioners in both archaeology and heritage continuously negotiate the connections between their fields. In these negotiations, heritage engages with archaeology to produce a range of contemporary activities, meanings, and behaviours, intended to invite and enable active public reflection, debate, and discussion around what is remembered and on the ownership and presentation of the past.

Our research explores how such negotiations might be designed and built within a critical ethical framework. To do so, we draw on design theories and practices, primarily those of values-led design [5,6,7,8,9], which move beyond a focus on products and services to place increasing emphasis on design’s potential to achieve wider impacts, for example social innovation and sustainable behaviours [10] (p. 515). In this article, we reflect on the redevelopment of an existing design tool for heritage-based storytelling, created in the context of the EMOTIVE Project [11], to adapt it for use by archaeology and heritage practitioners working on more diverse projects. In re-designing this tool (comprised of a deck of design cards and a methodology for engaging with them), we attempt to bring design methods, specifically values-led design methods, to archaeological and heritage practice and to customise them for the particular concerns of our community. Our efforts are motivated by a genuine desire to identify aids which practitioners can use to think through established normative ideas and to support attempts to explicitly work within declared value sets and ethical paradigms. Through an evaluation of the revised toolkit design, feedback on the cards themselves and on the workshop process wherein the cards are deployed, we examine how archaeologists and heritage practitioners negotiate the inevitability of values being laden into their practices, and how we might more self-consciously and directly engage with those values at all stages of our work.

The effort required to continually attend to values across the entire design process is substantial. One measure of whether the toolkit is sustainable is if the costs of the investment required can be borne by the communities of practitioners who are most immediately carrying them. While the wider scope of sustainability takes in the costs and benefits to a more diverse set of actors, from communities implicated in supply chains to the environment, we focus here on the sustainability of the use of the toolkit by its immediate users. For a tool is not truly functional if no one is able and prepared to use it. Sustainability, in this specific sense, is essential to successful functioning. We therefore assess the success of the cards, and the associated methodology through which they are deployed, using two basic criteria: (1) the extent to which their users succeed in integrating their values into the outputs produced and (2) the perception that the costs of the design exercise are justified in light of the benefits of the outputted design and the skills and capacities gained through the design process.

1.2. Intellectual and Social Context of the Work

A review of mission and policy statements of archaeological professional organisations, heritage agencies and university departments, including the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists’ recently published information sheet on Delivering Public Benefit from Archaeology [12] readily evidences a sense of self-conscious awareness of archaeological practitioners’ responsibility for public value. This active foregrounding of archaeology’s relevance to contemporary society’s needs, its social impacts, and potential for wider public and environmental benefit is likewise reflected in, and simultaneously promoted by, a growing body of critically reflective scholarship which explicitly discusses archaeology’s wider context, e.g., [13,14,15,16,17,18]. This positioning is furthered through the close links between archaeology and heritage, which directly wire the presentation of archaeological evidence, interpretations, and ideas into contemporary issues of identity politics, power, ownership and sustainability. The manifesto, for example, of the Association of Critical Heritage Studies [19], a body which concerns itself with the relationships between heritage and society, explains heritage as “a political act” and elsewhere it is described as a “cultural process”, whereby “values and meanings” are created in relation to the objects, places, and structures that are the typical focus of archaeology (and cognate disciplines such as architecture) [20] (pp. 15–16).

The positionality and values laden into (re)presenting the past and producing heritage from archaeology are widely recognized, and our collective acknowledgement of the challenges at hand both underpins longstanding efforts to promote multivocality and multiculturalism in research and (re)presentation by archaeologists and heritage practitioners [21] and contributes to motivating substantive bodies of work on decolonising archaeology and heritage practice [22,23,24]. At once, this very “ideological commitment to multiculturalism and multivocality” (as Wylie [25] (p. 577), describes it in her critique of critics of collaborative archaeological practice) risks opening archaeology even further to reactionary populism and complicity in oppression. Wylie [25] (p. 578), also see references therein) is amongst many who, across decades now, have recognised that no matter the context, we will always be confronted by “political precarity and intellectual uncertainty” as individuals converge around the archaeological record. To grapple with such instability, we must move beyond a focus on products, in favour of investing in community-led activist practices with “radically different tools, ones grounded in a stance of epistemic and political humility that take a recognition of uncertainty and the need for situationally tuned and responsive engagement as their point of departure” [25] (p. 584); also [16].

By our reckoning, then, to practice a self-conscious, ethically aware, socially engaged archaeology, at a minimum we need to make visible the position and values underpinning our archaeological work and its translation into heritage interpretation. This principle of values integrity (i.e., making values in a project internally self-consistent and robust to critical scrutiny) may be usefully understood as related to “empirical and conceptual integrity” as discussed by Wylie [21]. We have long assessed the integrity, the holds-togetherness, of the evidentiary basis and theoretical framework of archaeological projects. In contemporary practice, we add to this the assessment of the robustness of a project’s implementation of its values framework. This task is complicated by the process of translating archaeological research into heritage narratives, where we may be reliant on different representational framework(s) and are constantly confronted with the affordances and constraints of the tools, devices and infrastructures which underpin our practice [26,27,28,29,30]. The work of making values visible and interrogable must therefore be done across a project’s intellectual, ontological, and phygital (fully integrated physical and digital) components. In focusing on making values more embedded in our work and drawing attention to how they shape it, we recognise that this does not fully address problems arising from unconscious bias and lack of self-awareness of implicitly held values. Rather, these design activities are intended to elicit reflection on unconscious biases and to help participants to put their own perspectives in juxtaposition with those held by others.

Looking outside archaeology and heritage practice, design studies in particular stands out as a discipline which develops methods to explore, reflect on, and evidence the often-implicit connections between products and values. It focuses explicitly on the processes and practices of conceptual making (in contrast to physical making—or manufacture—the phase in which conceptual making is implemented), recognising that our world is designed, and that even early industrial designers tended work in a values-led fashion, sometimes with an aim to develop outputs which could improve the world and humans’ quality of life [31] (p. 33). Approaches developed in design studies, specifically more critical theoretical approaches which have emerged over the past 30 years, e.g., [5,6], provide tools we might adopt in undertaking the work of making visible the usually implicit influences and assumptions which structure design practices and outputs—in our case, specifically the practices and outputs associated with archaeology and heritage.

Given our sector’s current vested interest in social value, values-led design practices provide a framework which seems well suited to the challenges faced by a reflexive, ethically aware archaeology. Values-led design practices may be summarized as practices in the development of form and content which devote robust, considerable and persistent attention to “human value.” Human value, here, is understood as the sense of what is important to and meaningful for people. Fish and Stark [7] (p. 5) describe it as “properties of things and states of affairs that we care about and strive to attain.” Therefore, values-led design endeavours to draw attention to, and embed and manifest, these human values across the design process and into the designed outputs.

Designing with values in mind has a long history and intersects with a variety of different disciplines and epistemological approaches (e.g., Human Computer Interaction [8], values-led participatory design [9], universal design [32], inclusive design [33], value sensitive design (VSD) [6], etc. Costanza-Chock’s [5] (pp. 24–25) recent explorations of “design justice”, for example, arguably offer the most robust and developed vision, starting from the baseline that “the values of white supremacist heteropatriarchy, capitalism, ableism, and settler colonialism are too often reproduced in the affordances and disaffordances of the objects, processes, and systems that we design.” Even where value-sensitive or universalist approaches have been engaged to realise more equitable design outcomes, these have still tended to either mask which values do get embedded in the process or else assume that a common accessible standard is genuinely achievable even if all evidence points to the contrary [5] (p. 66). Design justice, then, recognises that it is impossible to design for all in a fashion that is truly just for all, and hence introduces a framework for “prioritis(ing) design work that shifts advantages to those who are currently systematically disadvantaged within the matrix of domination” [5] (p. 53).

What is critical for our argument is the growing recognition that design structures all aspects of life—it surrounds us, we are all implicated in it—as Escobar [31] (p. 5) puts it, “every community practices the design of itself.” It is through design, then, that we have the tools to create new worlds, or to maintain or destroy existing worlds, and recent critical design research thus converges not only on matters of designing for human and social justice, e.g., [34,35], but on related issues of wider environmental and climate justice. Escobar [31] (p. 44) calls the current global “structures of unsustainability,” and overall planetary crisis, a “design crisis”, and he is among many to argue that contemporary world-wide upheavals related to “climate, energy, poverty and inequality, and meaning” [31] (p. xi) are linked to our design drive for universalising, homogenising infrastructures that efface diversity and difference—and that obliterate the capacity to respond sensitively, locally, ethically—in favour of creating a singular “global village” [36]. Not only do particular values underlie this drive for a “one world world” [37], but they necessarily and actively quash alternatives. Grappling with this predicament, according to a growing number of scholars, requires that we “work with rather than ... ignore incommensurability” [36] (p. 227)—that we actively design our infrastructures such that they support “a world where many worlds fit” [31] (p. xi).

These efforts are what inspired our investigation into the means by which archaeologists and heritage practitioners negotiate the unavoidable admixture of values into practices, and how we might engage with them more intentionally and pervasively in our work. As practitioners with a digital specialism, we were especially attuned to the relevance of design to these endeavours given that we had all variously been involved in the conceptualisation, development and implementation of new digital products for public and specialist audiences. Accordingly, we started our collaboration aiming to extend an existing heritage storytelling-based design tool (developed within the EMOTIVE Project [11]) for archaeology and heritage practitioners who were developing and producing a variety of projects for different audiences. We subsequently tested this card-based design tool in a workshop setting. The process consisted of designing the design toolkit (process and cards), applying it with potential end users, followed by structured reflection, including elicitation of feedback on the tool itself and the experience of using it. The following paper therefore describes our experiences in applying values-led design methods and tools to the development of resources, tours, learning environments and other “experiences” for archaeological and heritage audiences. Below we review aspects of the general values-led design approach which seem immediately beneficial to archaeology and heritage practitioners. We then consider which elements required customisation and adaptation to be useful in our discipline, and identify several important limitations and misalignments.

In reaching for design methods and toolkits which attend to matters that may seem unnecessary at best, and twee at worst (in the sense that their use might generate an embarrassment that we should need such an intellectual crutch at all), we are acknowledging the real difficulty in maintaining constant ontological, epistemological and ethical vigilance throughout all aspects of our work. Deploying an explicitly values-led paradigm, enacted through exercises designed to prompt and capture thinking about the impacts of biases, value frameworks, perspectives and audiences throughout the process of knowledge production is, as we will discuss, inevitably imperfect in execution. This is not least because values are realised in practice, hence design specifications alone cannot account for what will manifest when the design itself is deployed in real-world settings [38]; also see [36]. However, our methodology provides a strategy for those involved in the production of diverse types of archaeological and heritage media (e.g., databases, maps, apps, exhibits, tours) to reveal and potentially hold themselves accountable to their moral imaginations.

1.3. Scope and Areas of Application

As for any practice, values-led design exercises and principles, as summarized above, could be adapted for use in our sector where the interpretation of archaeological evidence stands as the product or experience being designed. The design of disciplinary infrastructures such as recording systems, which embed their assumptions deep into the fundamental systems of archaeological and heritage work, can be reshaped through the structured consideration of their implicit frameworks. The production of media which are concerned with communicating high-level interpretations to different groups of people benefit from the implementation of formal design exercises because they are developed with specific audiences in mind, frequently involve the creation of physical and/or digital components as well as the production of “content”, and—crucially—intentionally aim to package archaeological evidence for public consumption by situating it in relation to contemporary concerns or “universal” ideals or qualities. Because this is where archaeology most directly and immediately interfaces with the public, and where our own values and various publics’ values meet, developing robust, conscientious practices in their design is critical.

However, developing these practices is difficult, first because design theory and practices are not part of the training and background of most archaeologists and heritage practitioners, consequently habits of structured design thinking are not established, and second, because the tools of values-led design are general and it is left to individual practitioners to think through the semantically high-level concepts of critical design theory to apply them to the narrower concerns of their domain. Further, deep interrogation of one’s own values, while arguably firmly embedded in our disciplinary training, remains a difficult exercise which requires significant personal investment.

To mitigate these issues, this project took the unusual but deliberate decision to embed a set of design cards containing prescribed value-oriented prompts, within a phased design methodology (discussed further below). This methodology provided an additional level of structure and information to increase the accessibility and usability of the cards by people without prior training in design methods and theory. These cards are intended for use while working to develop archaeological projects and heritage experiences that are ethically aware and accountable to the wider social, cultural, political and environmental impacts of their potential designs. The aim of the values-card toolkit and workshop is to help heritage practitioners to recognize and actively evaluate these impacts during project planning and development. While values-led design is predicated on shaping the whole design process, the design card as a tool targets specific, critical points in the process and aspects of project development, as discussed below in relation to this project’s results.

In our study, the projects subjected to the design exercise focus on the creation of digital resources for education, research and public engagement in archaeology, and involved practitioners working in archaeology, producing outputs for both archaeological and heritage audiences. By the time we were introduced to them, the developers of these projects had already accumulated a base of materials to inform the work, and some had an established set of likely or desired audiences. Using the workshop as a case study, we seek to investigate the challenges arising from developing more ethically aware and sustainable designs in (and outside) our discipline, while testing the efficacy of a dedicated toolkit in addressing those challenges.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Background on Design Cards

In this project we chose to develop and test a card-based design methodology to address the needs of archaeological and heritage projects in the interpretation scaffolding phase of their development. Card-based approaches are a long-established tool in design—including pedagogical approaches to learning design—and have proved to be valuable in promoting equal participation, while encouraging critical thinking and innovative ideas. They are also not entirely unfamiliar to archaeologists and heritage practitioners, as evidenced by the Heritage Futures Project’s adaptation of the “Thing from the Future” card game, aimed at encouraging the imagination of alternative futures [39]. As Deng et al. [40] (p. 696) put it “design researchers have found that cards can help structure design discussions, ensuring a design space is viewed from different perspectives. Cards can help speed up the refinement and iteration of ideas. Cards can also help kick off design discussion and foster focus shift when the discussion becomes unproductive [...] The small physical form of cards affords physical manipulation. Cards can serve as a physical reference during design discussion, facilitating communication and shared understanding.” These aspects of design practice were hypothesised to be particularly useful and relevant for archaeological and heritage projects because of their emphasis on multiple readings of the same materials.

Decks of cards have been developed since the 1970s to promote creative thinking and problem solving. During the 1990s card-based tools were mostly developed to foster user participation, mainly for the design of IT systems, while in the past two decades an increasing variety of card decks have been created for user experience (UX) and, more generally, human-centred design (HCD) of digital systems [41].

In a comprehensive review of card-based design tools, Roy and Warren [41] inventory and analyse 155 card decks, classified into three main categories: systematic design methods and procedures, human-centred design and domain-specific design. What emerges from their study is that while these tools are effective in facilitating creativity or providing tangible representations of design elements, they also can be difficult for users to understand and apply due to either over-detailed or over-simplified information. Interestingly, among domains neglected by existing card-based tools, the authors listed sustainable design, with only three decks developed to support more eco-friendly and ethical modes of transport and ways of living.

In fact, while various values-led design practices have been theorised and deployed for the past thirty years, it seems that there are still only a few card-based approaches that prioritize values in the design process. One example is the Envisioning Cards deck, designed by Friedman et al. [42] to evoke conversations and awareness of long-term and systemic issues in design. Further, and based on this deck, Shen et al. [43] have developed their “Value Cards toolkit”, aimed at facilitating students and practitioners in deliberating the social values that might be embedded in machine learning models. Separately, the contemporary Ethics for Designers toolkit, developed by Gispen [44], specifically aims to integrate ethics into design practice.

We highlight these examples because, as noted above, any design-focused work in archaeology and heritage must necessarily grapple with matters of ethics and positionality. As archaeology increasingly acknowledges its relevance and embeddedness in contemporary society, we as practitioners must consider the consequences of our work, what biases we are unconsciously embedding our designs, and who we are excluding. Moreover, participatory and co-design practices demand a diversity of voices and are therefore directly relevant to conversations in regard to multivocality and diversity in archaeology and heritage. A values-led design card toolkit (i.e., including both design cards and design methodology) has the potential to address these specific needs and priorities within our sector.

2.2. Designing the Values-Led Design Cards

The values-led design cards presented in this paper are an evolution of the EMOTIVE Design Cards, developed within the EU-funded EMOTIVE project [45]. Using these cards as a starting point allowed us to ground the design of this project’s cards and workshop within a framework already customised for use in the archaeological and heritage sectors. The purpose of the original EMOTIVE cards was to structure and guide the creative design process of emotive stories for and about cultural heritage sites. In our project, the aim was to refine and adapt these cards to make them suitable for use by practitioners without a design background and to make them applicable for a more diverse set of use cases, beyond the specific remit of site-based emotive storytelling.

The first of these adaptations was motivated by feedback from user testing of the EMOTIVE cards. In the past four years, several iterations of these design cards (see Figure 1 for examples of the latest iteration) have been evaluated during workshops involving multidisciplinary groups of design and archaeological and heritage professionals.

Figure 1.

Examples of the Values-Led Experience Design toolkit: an audience characterisation card (top) and an audience focused challenge card (bottom).

Users’ feedback on these different versions showed that the cards were perceived as overwhelming—both in terms of number and in terms of their instructional content—and more suited for those more familiar with the design process [45,46]. Based on these comments, and in recognition of the fact that most working in archaeology and heritage do not have a design background, in our project we chose to drastically reduce the number of cards—from 94 cards to 44 cards. This reduction in the number of cards was intended to lessen the amount of information workshop participants unfamiliar with the concepts presented on the cards would need to absorb. Presenting fewer options was also viewed as a tactic for making the exercise seem less overwhelming, effectively removing the cognitive burden created by too much choice. Through this process, cards which were considered less applicable to a broader and more diverse range of archaeological and heritage resources were discarded to reflect the scope of our current project. For example, EMOTIVE’s “Genre” and “Plot” cards were removed because they mainly pertain to storytelling for visitor experiences and could introduce confusion in other applications, such as a project aiming to design a map-based exploration of an archaeological landscape for archaeology undergraduates.

To make the cards more accessible to novice users, we also adjusted the graphical appearance of the cards, again removing detail and reducing the amount of information supplied. Inspired by the visually engaging and critical IDEO Lifeline Cards [47] and The Tarot Cards of Tech [48], the original prescriptive and detailed content was replaced by a limited number of questions, simply presented. In undertaking this simplification, the phrasing of the questions was adjusted, again with the aim of making the toolkit more flexible and applicable to diverse project requirements given the broader scope of use we had defined for our set of cards (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Examples of the Values-Led Experience Design toolkit: Prototype values-led design board and instructions.

As the revised deck was targeted at archaeologists and heritage professionals without design experience who are developing digital resources for practitioners and wider audiences, additional support was provided by organising the cards into logical, sequential phases: Vision, Concept and Design. Based upon existing innovation and delivery methodologies [49,50], the phases increase in detail and complexity and each terminates in a definite checkpoint including an associated output: Vision Statement, Experience Journey Map and high-level Prototype (digital/analogue/mixed), respectively. Each phase’s output was designed to record design decisions made during the phase and confirm their alignment to selected values, as well as to prevent premature exiting of the phase without achieving consensus among a design team, and to avoid solutionising. As described below, a deck of cards was created to accompany and support each of these phases, in addition to a series of value-specific cards, the Value Deck, and a series of “challenge” cards, the Challenge Deck (Table 1).

Table 1.

An outline of focus of each of the individual decks within the Values-Led Experience Design Cards pack.

2.3. Case Study: The DIALPAST User Experience Design Workshop

Our 44-card deck was tested during a three-day “Dialogues with the Past” (DIALPAST) workshop held in York, UK, in December 2019. The event was focused on the design of digital archaeology and heritage user experiences and organised by the Nordic Graduate School in Archaeology of the University of Oslo as part of their mission to connect doctoral students across Nordic institutions around practical and theoretical challenges associated with the study of the past. As the overall purpose of the workshop was to provide training to interested students, we decided to adopt a co-design approach to its running. Therefore, three of us (Dolcetti, Boardman and Perry) assumed a supporting role to assist participants in their design activities. The event offered an ideal opportunity to evaluate the efficacy of our cards in the context of a facilitated learning environment where the students knew the instructors and one another already (as this was a follow-on workshop to a more typical DIALPAST course offered in September 2019 in Rome, Italy, on Digital Pasts and Futures of Archaeology, and co-taught by one of the authors (Perry)). Importantly, participants were representative of the cards’ intended audience: novice users with diverse projects.

In total, six PhD students and early career researchers took part in the event. All participants were working on research projects aimed at developing different types of digitally mediated experience in archaeology and heritage, such as a VR library, 3D modelling of archaeological sites and artefacts, and a Web-based Visualization System for archaeological education. The workshop was hosted by the Archaeology Department, University of York and led by six facilitators, including the authors. Four distinct design sessions were run across three days. Each session was supported by one or more of the decks of Values-Led Design Cards (which, of note, had not been circulated amongst the participants prior to the DIALPAST workshop). Each participant was paired with a facilitator to be their guide and critical friend throughout the design process.

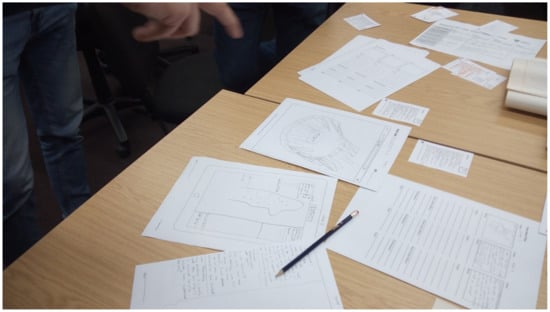

Evaluation during the event was carried out by means of facilitators’ personal observations and audio recordings of the various design activities. Consent was sought by means of an information sheet and consent form circulated to both participants and facilitators at the start of the workshop. Mid-point evaluations were also conducted at the end of each design phase to allow participants to discuss their progress in small groups and to gather feedback on their design processes (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

“Dialogues with the Past” (DIALPAST) workshop, mid-point UX design evaluation. Pictured here are several values-led design cards, completed persona cards and experience design worksheet, and multiple storyboarding and wireframe templates filled in by the participant designer as part of their design process (credit: DIALPAST Workshop contributors).

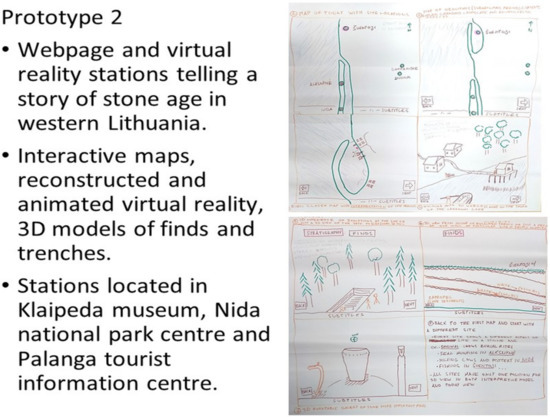

The workshop ended with a final group discussion where participants presented their design journeys, reflecting on developments from each phase and defining next steps for their prototype digital outputs in the form of concrete actions (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

DIALPAST workshop output: final presentation by one of the participant-designers. Pictured here on the right is the experience journey of a hypothetical user of this interactive digital experience (credit: DIALPAST Workshop contributors).

A further evaluation was carried out eight months after the original workshop, for which further consent was sought via an email communication about the intent of this final round of evaluation, followed by email distribution of a small number of follow-up questions to those who agreed to participate. In total, five participants and three facilitators (of a total of six participants and three facilitators) responded to our request to contribute to the evaluation and submitted email responses. The primary aim of this additional step was to assess the level of knowledge retention, attitudinal change, and the extent to which the values-led design toolkit had been taken up and used outside of the facilitated workshop environment.

The qualitative dataset used in this study was collected via observations, group discussions and interviews supported by audio recordings and emails. Qualitative data were coded and analysed using thematic analysis, a method used to identify and interpret patterns or themes across data [51]. Themes can be identified in two ways in thematic analysis: firstly, using a bottom-up or inductive approach where themes are data-driven and strongly linked to the data themselves, without trying to fit into the researcher’s analytic preconceptions. As Braun and Clark [51] (p. 85) point out, “researchers cannot free themselves of their theoretical and epistemological commitments, and data are not coded in an epistemological vacuum”. Therefore, many projects integrate a top-down or deductive approach where themes are analyst-driven and tend to be guided by the researcher’s theoretical or analytic interests in the area. In practice, aspects of each of these are frequently combined and thematic analysis can often move iteratively between data and previous literature or theory. Initially data are coded and collated, and then are analysed to see how they may combine to create overarching themes, and finally themes are revised and refined and all the relevant coded data extracts within them are collated. In our study, we adopted a combination of inductive and deductive approaches to coding, identifying six main codes that were then refined and collated generating three final themes (discussed below). The choice of these themes and codes is, of course, subjective. However, our choices were guided by the literature, as discussed below. In order to ensure anonymity, all respondents have been assigned pseudonyms [52], but below we distinguish between facilitators and participants, as well as identify at which point in the evaluation process we gathered their feedback (e.g., post-workshop follow-up; final presentation; workshop evaluation, etc.).

3. Results

In evaluating the outcomes of the values cards and workshop itself, we considered the reported impacts on the working practices of participants together with reflections on our own observations of the process. As explored in detail below, participants’ responses were strongly positive and impacts on their current and future practice were universally identified, creating the impression that the cards, and their associated use in a facilitated workshop setting, is a successful one. However, a closer consideration of the character of the reported impacts against the intended impacts of the toolkit and workshop, as understood by us as their creators, suggests that this impression is somewhat misleading. While the values-led card toolkit deployed here has real, positive effects on participants’ designs of their own projects, and seems to have achieved the core aim of embedding values in the design of projects through more explicit consideration of audiences’ needs, beyond this it falls short of its stated ambitions.

Although the experience of workshop participants and their feedback provides useful information on the perceived success of this values-led, toolkit/cards approach, it is essential to reflect on the extent to which participants were actually able to recognize values embedded in different aspects of their projects, assess their impacts, and take values-led design decisions. In our reflections, we interrogate specifically why values were only intensively attended to by participants at an early stage in the design process—namely in the context of identifying and characterising audiences. Secondly, as a consequence of this observation, we explore how the toolkit and workshop format might be further adjusted to ensure that a values-led focus more directly affects other parts of the design process. Finally, we reflect on broader implications for archaeological and heritage work.

3.1. Successes and Difficulties Working with Design and Values

While the workshop facilitators—a group which included us, the values-led card creators, and the event organisers (who were recruited by the DIALPAST network)—were familiar with and supportive of the concept of critical design, and values-led design specifically, no assumptions were made regarding its suitability, acceptance and successful application amongst the DIALPAST students. In other words, although the students had been introduced to the concept of purposeful design of archaeological research/outputs by Perry at a DIALPAST course several months earlier, there was no expectation that they would endorse the toolkit provided, and very little preparatory material was made available to ease them into the process. Based on post-workshop interviews and informal discussion with participants, we know that participants were not experienced users of formal design tools like those presented here, nor were they especially familiar with the tenets of design in general. This lack of background in design theories and methods leads to some of our proposed further modifications for the values-led design toolkit and its deployment in a workshop setting, discussed below.

Despite the absence of on-boarding of participants, the first impressions and feedback gathered from both participants and facilitators, during and after the workshop, indicate a positive response to the presented design toolkit, including the cards, as reflected in Keith’s comment: “I also remembered the whole thing being highly creative, collaborative and iterative—which I think is a tremendously useful way of approaching the design of digital tools (so often developed by a small group in isolation” (Facilitator, Follow Up Evaluation).

As previously mentioned, each participant was paired with a facilitator whose role as critical friend was to guide and support the participant through the design process. The critical friend was an important element in the design of the workshop and was highly valued by participants. Per one student, “The best ingredient of the process has to be the “Critical friend” that in a constructive manner drove the design process forward through dialogue” (Grant, Participant, Follow Up Evaluation). Another student foregrounded the investment of the facilitators, which they tellingly described as “teachers”: “The amount of attention from teachers was incredibly helpful. They tried to make each question as clear as possible and forced us to come up with answers. It was a really cool mind exercise” (Liam, Participant, Follow Up Evaluation). The role of teacher-facilitators is clearly important; however, we note that this is related to the design of the workshop itself rather than the values-led card toolkit which was developed to be deployed in a variety of contexts (not necessarily workshop specific).

Although the workshop experience, including the use of the “critical friend” mechanism in particular, were characterised positively, there was a reported misalignment between expectations going into the workshop, the activities undertaken and the outcomes. Exploring these in more detail reveals some of the main challenges to novice practitioners working with values-led design. Several participants noted in their final presentations that the workshop experience was not what they were expecting and that the fast pace of the activities, combined with the high level of critical engagement and reflection required, had been challenging yet transformative. One participant, for example, described their experience over the three days as “My journey” and “I also remember that time was always short, but this was not necessarily a bad thing, but contributed to a more “has-to-deliver process” (Grant, Participant, Follow Up Evaluation).

That participants felt they gained a lot but recognized there was more which could be accomplished suggests that they were learning actively and developing their practice through being challenged and pushed slightly beyond their comfort zones. On the other hand, as workshop leaders we recognize that participants did not succeed in identifying or taking into consideration values across multiple aspects of their designs. This misalignment was not characterised as a source of disappointment, as is clear in the quote above, nor did it lead to expressions of frustration by participants in feedback. However, it reflects important limitations of the toolkit as a mechanism for embedding values-led design methods throughout the development of a project.

The difficulties faced in implementing values across an entire project were reflected at one level by the fact that during the final evaluation only one participant chose to focus on and structure their presentation in terms of the three values they identified as key for their project: Accessibility, Freedom and Curiosity. This participant described explicitly how these values influenced and were manifested in the various iterations of their experience design. However, the other five participants did not provide explicit reflections on their chosen values.

The difficulties of moving from identifying a value as important to enacting it were likewise apparent. For example, one participant selected Equity as a core value, but included no women in a list of potential collaborators for their project. Because this occurred in a workshop setting, there was an opportunity to discuss limitations within the participant’s professional network and to identify potential solutions, such as suggested contacts from a number of the Facilitators’ networks. This example highlights a limitation of the cards themselves. The Challenge cards would have prompted thinking about diversity in this context, however time was not available within the workshop to apply the whole deck systematically and therefore it only emerged through facilitation. Multiple strategies, including card-based exercises, collaborative working, and facilitated review are needed to promote accountability and highlight any potential unconscious bias.

This kind of partial success in enabling participants to take values into account was characteristic of the outcomes of work with the toolkit on any given part of the project design, including the aspects most extensively addressed by the majority of the workshop participants: audience and empathy. As argued by Sengers at al. [8] and Iversen et al. [9], in fact, even if made explicit through the process, values might not be successfully embedded in the design itself, unless the designer becomes fully self-aware of their own unconsciously held assumptions and realises how much they shape how we experience the world.

3.2. Emphasis on Audience and Empathy

Feedback and observation demonstrated that a greater focus on audience needs, expectations and the overall experience journey during the Concept and Design phases produced the most significant shift in participant user-experience designs. The extent to which all participants spoke of, and about, their identified end-user audience or audiences was noticeable in their final evaluation presentations. For some, this was the first time they had actually identified their target audience. For others, it was an opportunity to review previous, perhaps unconscious, definitions and/or assumptions they had made about their audience(s), their needs and therefore the purpose of their project. As one participant noted in their final presentation, “The purpose [of my project] has changed for me a bit ... I really liked when we did the personas it really helped me to think about who is going to use this and why.”

Increased attention to audience was also noted by the Facilitators. As Keith (Facilitator, Follow Up Evaluation) described it, “I did enjoy the act of really thinking hard about audience demographics at the early stages of design (at the outset of development). It was very useful to be thinking carefully and in detail about who might be interacting with your product—and to have useful tools for getting to grips with your audiences.”

Liam (Participant, Follow Up Evaluation) made explicit his lack of familiarity with any sort of audience characterisation, noting that “During the workshop I understood that even though public archaeology projects were always on my mind I never really thought about who are the people that will be participating in my events/projects, how to group them according to their needs and personalities and select the target groups.” Grant (Participant, Follow Up Evaluation) went further in hinting at a rather ubiquitous weakness among archaeological practitioners, namely the tendency to use oneself as the only reference point for an intended audience: “It is so easy to not include the audiences in the design process working at a museum for example. It’s much more convenient to develop products that you think are great without having a dialogue with potential audiences.” He then went on to speak specifically about aspects of the card deck that supported his personal development as an experience designer: “The ‘Persona’ cards were very helpful in challenging me to, on a detailed level, think about my audiences, their expectations and needs. Furthermore it helped to understand why I’m designing this specific experience” (Grant, Participant, Follow Up Evaluation).

These sentiments were echoed in the feedback from the workshop facilitators, who additionally noted their surprise in realising that most participants did not have an explicit definition of their audiences, and therefore their audiences’ needs and expectations, before beginning their user experience design work. Per Bethany, “I especially remember the positive response by the students to the practical work with the cards. I think my strongest realisation was that the workshop was so needed, and necessary, as so many of the students were not aware of target groups and not used to thinking “who am I doing this for” (Facilitator, Follow Up Evaluation).

These comments reflect the clear effectiveness of the values-led design workshop in enabling contributors to appreciate the direct relationship between their values and their target audiences, including their assumptions about those audiences. Even here, though, some constraints of the toolkit appear. It was noted by Thea, one of the workshop facilitators, that one of the limitations of the event and therefore of the designs produced over the two days, was the lack of actual audience representation and participation: “So it is something that we need to be thinking about when you’re developing it further, you need to understand your user journey for instance. You need to have input from those outside audiences and then we need to have input from one another.”

Recognition of the need to cross-check with actual users to inform the design process more rigorously can be construed as a positive outcome enabled by the toolkit. However, at the same time, this comment points to a wider issue: that it would be beneficial to incorporate interaction with potential users to enable these cross-checks from the outset. Expanded interactions with a wider set of stakeholders imply work and shifts in practice which go beyond the capacity of a single workshop series, as discussed below (see Section 4). In parallel, results point to a limited definition of audience, as equating to the general public rather than any professional end users of a design, which might include for example peers and other practitioners. One participant noted that after the workshop they integrated the values-led toolkit mainly into a proposal for “educational or other public project” (Nick, Follow Up Evaluation), thus seemingly reflecting a tendency within the sector to relate “audience” strictly to the non-specialist public domain (as opposed to the professional and technical archaeological domain).

These results highlight the limited exposure within archaeology and heritage sectors to well-established and emergent design methods and practices. Therefore, the workshop demonstrated the potential of supporting immediate advances through a toolkit-based methodology, increasing basic design knowledge and appreciation of the complexities of a design process. These broader impacts are reflected in the participants’ reported increased awareness of the potential of design to intervene in other aspects of their projects and in their actual or planned use of the toolkit or elements of it within their own professional communities.

3.3. Transferability of the Values-Led Design Toolkit

While recognition of embedded values and evaluation of their impacts was most prominent in relation to the persona development part of the design process, through motivating reflections on audiences and their experiences, the toolkit introduced the idea that other parts of the project are also designed at a high level. In particular, the “Concept” cards within the design pack required the workshop participants to take a more holistic approach to developing their high-level experience design. They were encouraged to consider the entire end-to-end user experience or “journey” (i.e., the whole path that leads the user to find and then engage with the designed medium(s) and then move on), rather than focus only on individual interactions with the final output(s), e.g., an App or Information Board.

The use of the Concept cards as part of a holistic design methodology revealed the true scale of the participants’ proposed projects at an early point in their development. This increased awareness of their projects’ complexities, which emerges at an early stage in project planning through the use of any prototype-based iterative design methodology, was a clear benefit. The workshop activities resulted in the creation of more accurate definitions of each project’s scope and in a more holistic view of the end-to-end user journey through the experience.

These activities also highlighted that some participants did not possess all the skills and knowledge required to successfully deliver their project, leading to a recognition that collaboration with other professionals would be necessary. As noted by Rebecca (Participant, Workshop Evaluation), “To do that and also to implement all the new components of this basic visualization system I need to work with IT specialists and I also have someone that I hope will help me to develop this.” In gaining a greater understanding of the scope of their projects, we believe the values-led toolkit, if not elucidating the values embedded in all aspects of these projects, did succeed in highlighting for participants that all parts of their projects are designed and that values need to be considered throughout the entire design process.

All participants stated that they intend to reuse the values-led toolkit deployed during the workshop. Unfortunately, many participants and facilitators noted that opportunities to apply the toolkit approach again had been severely curtailed due to the 2020 global pandemic. However, even in these adverse circumstances, a small number of participants noted that they had in fact incorporated the toolkit into subsequent project proposals and postdoctoral applications. One participant stated that they would “apply it to all the case-studies of my dissertation project” (Rebecca, Follow Up Evaluation); that is, they would use the cards to critique and evaluate others’ archaeological and heritage designs/outputs rather than simply to create their own new experiences.

Another participant noted the impact on their reception of projects, stating, “… later when we were planning and participating in some educational archaeological events, I found myself quite critical and most of my insights were brought from the workshop” (Nick, Participant, Follow Up Evaluation). A similar impact can be seen in Grant’s (Participant, Follow Up Evaluation) response, discussing his remaking of the workshop design cards. He noted that, “I have used [the workshop design cards] for inspiration to create my own set of cards that are more accustomed to the environment I work in”. Other participants commented more generally that following their attendance at the workshop their understanding of and rationale for design and the application of design tools had increased and that this had expanded their view of where, when and how these could be used. Nick (Participant, Follow Up Evaluation), for example, noted that “The workshop showed me that there are more tools for design and its process than I previously thought and some tools are easy to find online.” Grant (Participant, Follow Up Evaluation) spoke more generally about the utility of the overall methodology: “The understanding that this type of framework, that the cards provide, are vital for a successful design process has really opened my eyes.”

These participant and facilitator comments provide insight into both the baseline level of general awareness of the design process and the potential for real impacts through interventions such as the use of a toolkit in a workshop. To understand the extent of these impacts, critical reflection in the context of the aims of the toolkit, as we conceived it, is needed.

4. Discussion

As noted above, feedback gathered from both participants and facilitators indicated a generally positive response to the toolkit. Most participants characterised it as very useful in terms of consciously guiding them through a more structured approach to values, notably by foregrounding critical reflection on values, purposes and audiences at the very beginning of the design process. Responses gathered during the follow up evaluation revealed a significant level of independent and confident re-use of the toolkit. This indicates that while participants worked in a facilitated context during the workshop, they gained some degree of self-sufficiency in the use of the toolkit. Participants, importantly, recognised the necessity and benefit of comprehensive design work prior to building and implementing any elements of the user experience. Participants further expressed appreciation of how the toolkit helped them rethink and ultimately reshape their research designs in a more robust and meaningful way. Feedback highlighted the benefits of its mechanisms for moving consideration of the audience/end users’ needs and expectations early in the project lifecycle, accessing and applying expertise through a collaborative and iterative design practice, defining more fully the true scope and complexity of the project and recognising the need to work with different stakeholders and skillsets in order to successfully deliver the project.

While the toolkit’s use had positive impacts in this workshop, the feedback received and our assessment of it against the workshop’s aim to promote critical reflection on diverse values across all aspects of a project’s design suggests that further substantive adjustments to the toolkit are needed. In particular, upon reflection on the feedback, it is clear that mechanisms and opportunities provided to participants to support engagement with what constitutes “values” as a whole and the definitions of individual values were insufficient.

In the DIALPAST workshop, there was a general conflation of the concepts of “values-led” and “audience-aware”, resulting in relatively limited consideration of non-audience-based design values such as environmental care, as exemplified by the comment, “I think the workshop was very useful in thinking of all the aspects of audience aware design” (Bethany, Facilitator, Follow Up Evaluation). To address this, one might add prompts designed to provide, or provoke consideration of, more explicit definitions of values. These considerations could include a stronger sense of how the term is defined in values-led design, the definitions implied through the Value Cards themselves, any shared core values of the cultural heritage sector, and agreement of personal values within the design teams (as is incorporated in Gispen’s [44] “ethical disclaimer” and “ethical contract”). Based on these prompts, collective discussion focused on the meaning of the values and whether such meanings were shared or not, could be included within the toolkit. While such an explicit discussion might work in some settings, it would be naive to imagine that these conversations would be universally productive or positive. In some groups, such a discussion may be counterproductive and generate tensions that cannot be resolved. In this situation, the appropriateness of this toolkit must be carefully considered. It must be emphasized that the time-intensive nature of this kind of discussion under the best of circumstances—and the need for substantial mutual trust and goodwill—are real obstacles, particularly if incorporated into a short-life workshop with a newly convened group of participants see also [46].

As is clear from the discussion above, the workshop structure and format itself requires careful reconsideration. On the one hand, group discussion and interventions by facilitators had clear benefits, encouraging participants to consider new perspectives or values introduced by others in their group, an outcome which would not likely have been achieved by use of the cards alone. On the other hand, the social constraints created by a group workshop, whether that group is newly constituted or represents an existing dynamic, places important limitations on the ability of participants to take a values-led approach to their projects’ designs. In our assessment, during the DIALPAST workshop the difficulties around arriving at shared understandings of values manifested as a tendency for participants to choose Value Cards based on a perception of what was expected from them, implying that there was a wrong and right answer when selecting values. In one case, as observed by one of the authors, the identification of the authentic values of the project only emerged through an informal discussion about the participant’s previous projects.

Beyond these key considerations, the necessary time limitations of a workshop, when combined with the time intensiveness of values-led design card exercises, creates further challenges. In addition to needing time for further consideration of the characterisation of values, the need for more points at which progress was reviewed and alignment between stated intentions and execution checked, for example, likewise suffered from the compressed format.

In sum, the gap between our aims for the exercise, the intentions of participants to put values into their designs, and the extent to which they were enabled to enact them consistently was apparent. We suggest that to bridge these gaps between expectations, intentions, perceived impacts, and observed changes in practice, wider supportive mechanisms are needed which go beyond the remit of a toolkit. Below we discuss these proposed mechanisms in more detail. It is worth noting that our recommendations have parallels with those of Shilton [53], whose multi-year ethnography of a computer science laboratory led her to identify a series of “value levers” necessary to enable critical thinking about values and to embed them into everyday design practices and design outputs. Crucially, Shilton [53] (p. 394) is clear that the structure and culture of one’s working environment are essential to realising a vision wherein “just and equitable systems can be built by design”.

Building a Community of Practice

The participants in the DIALPAST workshop were evidently aware of the complexity and difficulties of the work in which they were engaged. Their comments suggest that through their work with the toolkit they were able to better appreciate the highly contextualised and contingent nature of design projects and recognise the potential role of the design process in moving the design and designer(s) iteratively from a position of uncertainty to certainty, with one participant noting, “I now understand that a design process can be beautifully messy and that it should be. By being more open for change I have gotten more dynamic in my approach to others such as co-workers or the public” (Grant, Participant, Follow Up Evaluation). This comment also points us to our ultimate aim as authors of the toolkit and facilitators of the workshop: the ability to integrate design more widely into archaeological and heritage work. At once, it also highlights the importance of doing design work in interaction with peers and colleagues, implying work within a community of practice that allows for, and ideally supports and encourages, these approaches.

Establishing a wider community of practice would help to address some important limitations noted in our toolkit-based work. For example, some participants noted that they did not have the skills necessary to carry out some aspects of their projects, particularly technical aspects. This kind of comment highlights the need for support from a wider cohort of practitioners engaged in the design process. Someone incorporating an interactive 3D model of an artefact into their project’s design might not be aware of the implicit ways in which values, such as those related to issues of data sovereignty, can be built into the design of the user interface. A wider community of practice could allow this to be addressed through engagement with peers with relevant expertise.

In the context of the workshops, we also noted a general misconception of design as something confined to specific types of projects (R&D or public outreach) rather than a creative problem-solving process applicable to all aspects of archaeological and heritage practice. As one facilitator stated, “I hope to deploy aspects of this approach if I can ever get any R & D projects off the ground” (Keith, Facilitator, Follow Up Evaluation). These comments underscore the persistent issue of the lack of design knowledge in our sector and highlight the need for broader education in the design discipline and design principles prior to adopting specific design methodologies or tools. In order for this toolkit to be successfully implemented in our core archaeological and heritage practices, it needs to sit within a broader set of conversations about how we work and be embedded within an organisational culture in which it is both supported and prioritised.

In this context, participants’ comments touched on what is identified by Oliver et al. [54] as one of the key challenges and risks of co-production: an organisational culture and environment in which the toolkit is valued, encouraged and fully implemented: “In the beginning it seemed to me quite silly to use colour markers and pencils, cutting paper. I think my colleagues would look weird at me if I did this at work :). But. Nevertheless, I changed my mind about colour pencils and markers. And at least painting colourful new projects with Nick (who also visited this workshop) would not feel as stupid” (Liam, Participant, Follow Up Evaluation).

This implies that tools such as design cards and activities such as paper prototyping were not present in the participants’ normal working environment. As for any other methodology, this toolkit needs to be integrated within existing organisational processes, promoted by senior management and adequately resourced in order to be successful.

This is a critical point in the development of a wider community of practice around design. Although comparative research within the archaeology and heritage sector is not yet available, the essence of the participant’s “silly” feeling can clearly be seen in the body of research which considers creativity in organisations, and specifically the subset which investigates the forces which act to block the application of creative practice. Researchers such as Bills and Genasi [55] and Gomes et al. [56] note that despite creativity being a prerequisite for desirable practices such as continuous improvement and innovation, a common feeling associated with the creative practice, outside of the creative sector itself, is embarrassment, linked to an underlying fear of failure, humiliation and rejection. It is in relation to this aspect of personal risk that Kirk [57], quoting Henri Matisse, talks about the “courageous act” of creativity. Bills and Genasi [55] use this externality to argue that creativity, though often considered a personal attribute, is also a social artefact, and as such is blocked in organisations where productivity and associated productive behaviour is desired, valued and rewarded above creative behaviour unless it results in a positive outcome. According to them this situation is, counterintuitively, exacerbated by the advancements in technology as process times are reduced and “thinking time” eliminated. Design practices, then, with their time-intensive characteristics, can be used to reintroduce this thinking time.

5. Future Developments

While the impact of the workshops was limited in some ways, as noted above, participation in the workshop succeeded in changing participants’ understanding of the process of project development and their approach to it, both through engagement with design practices in general and values-led design methods specifically. The strength of the impact on core practices involved in project development is reflected in participant and facilitator statements of their intention to employ the method in other projects within their own institutional and research communities. Importantly, all but one workshop participant noted that they had discussed their workshop experience and outputs with their home institution peers. Rebecca (Participant, Follow Up Evaluation) described it as being “very enthusiastic about the design process, and I have discussed it with colleagues and friends.” Another participant said more specifically that “The card deck that was used during the workshop was just a great set up of tools that I already have used in discussion with others at my workplace or in other projects … At my workplace I have used the design tools given to talk and inspire in a digital development team that has been set up” (Grant, Participant, Follow Up Evaluation).

Insights from the DIALPAST workshop suggest the need for a toolkit which facilitates a multistage process that introduces design practice in general, then values-led design in particular, before defining and scoping values and then project phases or aspect-specific implementation tasks. Future deployments of this toolkit could include additional steps to provide better knowledge of fundamental design concepts and support the elicitation and implementation of selected and emergent values across all design process phases. Furthermore, investing in the (re)design of our normative disciplinary methodologies and workflows (e.g., such that the toolkit is embedded in the earliest stages of programme conceptualisation; that time and resources are dedicated to the design process in project budgets and milestone setting, etc.) is a necessary step to fully integrating values-led methods and tools into everyday practice.

Further, the toolkit poses a number of targeted questions intended to incorporate environment-centred design (i.e., an approach which encompasses human and non-human needs [58]), including introducing environmental sustainability as a design concern. However, the current version of the toolkit only addresses these issues relatively late in the values-led design process and predominantly via the Challenge Cards. Given current societal concerns with human-environment interactions and impacts, we suggest that future versions must ensure that consideration is given to both human and non-human matters of interest throughout all phases of the design process.

Working with values within a co-production environment is a complex task [9,54,59], requiring multiple iterations and often manifesting as a process of “trial and error”. In any context, integrating a values-led framework into design activities will be difficult to achieve and our experience in the DIALPAST workshop confirmed the challenges inherent in working with values: they are open to multiple, perhaps conflicting definitions, and operate across several professional and personal levels. This difficulty may also explain the scarcity, as discussed in Section 2.1, of values-led card-based design toolkits within the wider design field.

6. Conclusions

In our experience, many practitioners in archaeology and heritage are open to design methodologies and are sympathetic to the values-led framework. Yet, they face multiple challenges when attempting to put the ethos of values-led design into practice. Key challenges include exploring different practitioners’ understandings of specific values, understanding how design practices are used to address different aspects of a project, and developing awareness of and engaging with critiques of design theories and methods. All of these challenges are substantive and share a common theme: ongoing investment in developing the designer’s own practice and their relationships within the wider community surrounding the project.

There is a strong imperative to engage with these challenges in the context of critical heritage and archaeology today. Within the current debate around public and collaborative archaeological practices, Wylie [25] (p. 583) has argued that to transform archaeology it is crucial “to take an activist stance aimed at transforming the institutions and structural conditions that configure its practice” and while this activism in some cases requires “disengagement, a refusal to pursue an archaeological research agenda, or the hard politics of an oppositional stance. In others, it may be possible to work from within”. To pursue positive actions, we need spaces that encourage collaborations and tools that help us to enact transformations, ensuring that our practices are genuinely open and ethical [16,30].

Designer accountability sits at the core of values-led practices and actively engaging with these challenges to promote open and ethical work requires us to be accountable both to ourselves and to others. This is reflected in the design of the toolkit, which encourages anyone deploying the toolkit in making their own designs to hone their skills and to enable their co-design community to do so as well. By our design, the toolkit both needs and can help build communities of values-led practice embedded within organisational cultures where they can be nurtured and prioritised.

The clear enthusiasm for the values-led design approach was evident during and after the workshop, and the reported ongoing use and sharing of the method demonstrates that the rewards of engaging with values-led design approaches are well worth the costs for the people involved. The ultimate measure of sustainability is whether the community who must maintain and develop the practice can afford the expense of doing so and is willing to pay for it in terms of both time and resource. By this metric, the participatory values-led design card toolkit succeeds. The challenges, while real, are the good kind, the ones that push us to intentionally shape an ethically aware, socially engaged archaeological practice and to create real value for the larger communities in which our work is embedded.

Author Contributions

The authors confirm the contribution to the article as follows: F.D. led the preparation of the paper and contributed to the design of the values-led card-based design methodology. C.B. led the design of the values-led card-based design methodology. F.D. and C.B. conducted the qualitative data analysis. R.O. and S.P. contributed written content across the article, primarily to the Introduction, Materials and Methods, and Discussion sections. F.D., C.B. and R.O. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, and read and approved the submitted version. S.P. was the primary coordinator of and liaison with the University of Oslo for the DIALPAST workshop. Funding was secured from the EU COST Action ARKWORK and the EU-funded EMOTIVE Project by S.P. and from the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) by C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by funding from multiple sources, including the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 727188 (the EMOTIVE Project); and the European Union’s COST Action ARKWORK (CA15201: Archaeological practices and knowledge work in the digital environment); as well as the University of Oslo Nordic Graduate School in Archaeology’s “Dialogues with the Past” (DIALPAST) PhD research school which enabled us to come together for the workshop and finally the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC). Open access publication of this work was supported by the University of York’s Digital Creativity Labs (www.digitalcreativity.ac.uk accessed on 15 March 2021) jointly funded by EPSRC/AHRC/InnovateUK under grant no EP/M023265/1.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Arts and Humanities Ethics Committee of the University of York (28 January 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to our co-facilitators, participants and hosts on the DIALPAST workshop, including the University of Oslo, as well as collaborators on several early iterations of the workshop and cards from the University of York and from participating institutions associated with the EU COST Action ARKWORK. Through these contributions, we have received in-depth feedback from individuals at various stages of their careers based in two dozen different European countries. The original storytelling-specific, non-values-oriented cards from which our research has grown were developed in the context of the EMOTIVE Project with key contributions from Laia Pujol, Narcís Parés and collaborators at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra, as well as other members of the EMOTIVE team. The work was approved by the Department of Archaeology’s Ethics Review Committee, under the auspices of the University of York’s Arts and Humanities Ethics Committee.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ahmad, Y. The Scope and Definitions of Heritage: From Tangible to Intangible. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2006, 12, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmion, M. Understanding Heritage: Multiple Meanings and Values. Ph.D. Thesis, Bournemouth University, Bournemouth, UK, 2012. Available online: https://eprints.bournemouth.ac.uk/20753/3/MARMION%2C_Maeve_Marie_Marmion_PhD_2012.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- O’Keeffe, T. Heritage and Archaeology. Encycl. Glob. Archaeol. 2014, 94, 3258–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Native, A.; Lucas, G. Archaeology without antiquity. Antiquity 2010, 94, 852–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza–Chock, S. Design Justice: Community-Led Practices to Build the Worlds We Need; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-0-262-04345-8. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, B.; Hendry, D.G. Value Sensitive Design: Shaping Technology with Moral Imagination; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-0-262-03953-6. [Google Scholar]

- Fish, B.; Stark, L. Reflexive Design for Fairness and Other Human Values in Formal Models. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.05084. [Google Scholar]

- Sengers, P.; Boehner, K.; David, S.; Kaye, J. Reflective design. In Proceedings of the CC ’05 4th Decennial Conference on Critical Computing between Sense and Sensibility, Aarhus, Denmark, 20–24 August 2005; Bertelsen, O.W., Bouvin, N.O., Krogh, P., Kyng, M., Eds.; ACM Press: Aarhus, Denmark, 2005; pp. 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Iversen, O.S.; Halskov, K.; Leong, T.W. Values-led participatory design. CoDesign 2012, 8, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtonen, A. Approaching Change with and in Design. She Ji J. Des. Econ. Innov. 2020, 6, 505–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emotive. Storytelling for Cultural Heritage. Available online: https://emotiveproject.eu/ (accessed on 24 September 2020).

- CIfA. Delivering Public Benefit from Archaeology. Available online: https://www.archaeologists.net/sites/default/files/news/Public%20benefit%20leaflet.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Belford, P. Ensuring Archaeology in the Planning System Delivers Public Benefit. Public Archaeol. 2020, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilley, H.; Ball, L.; Cassidy, C. Research Excellence Framework (REF) Impact Toolkit; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2018; pp. 1–40. Available online: https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/resource-documents/12319.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2021).

- Guttmann-Bond, E. Reinventing Sustainability: How Archaeology Can Save the Planet; Oxbow: Oxford, UK, 2019; ISBN 978-1-78570-992-0. [Google Scholar]

- Kiddey, R. I’ll Tell You What I Want, What I Really, Really Want! Open Archaeology that Is Collaborative, Participatory, Public, and Feminist. Nor. Archaeol. Rev. 2020, 53, 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenzweig, M.S. Confronting the Present: Archaeology in 2019. Am. Anthropol. 2020, 122, 284–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, A.B. Assembling “Effective Archaeologies” toward Equitable Futures. Am. Anthr. 2020, 122, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACHS. Association of the Critical Heritage Studies. Available online: https://www.criticalheritagestudies.org/ (accessed on 15 January 2021).