Abstract

The complexity of the public sector generated by the mobilisation and use of significant financial resources, national cultural factors, the heterogeneity of the provision of public services, the numerous interested parties, the increasing demand for the quality of public services, the information asymmetry, require an actor to provide credible assurance regarding the proper management of public financial resources. In this context, performance audits are the link between public sector entities and stakeholders. The research has two components: the first component analyzes the degree of harmonization of the regulations specific to the performance audit in Romania with the International Standards of Supreme Audit Institutions (ISSAI); the second component analyses the degree of transparency of performance audit information by the SAIs of the EU Member States, through their official websites. In this regard, we have resorted to an in-depth longitudinal study, content analysis and disclosure index. The research results highlighted that the Romanian SAI has adopted in its normative framework the foremost ISSAI provisions on performance audit and the harmonization degree has systematically improved correlative with the regulatory revisions. The degree of disclosure for performance audit-specific information by the EU member state SAIs is high.

1. Introduction

Our research approach is based on the importance of public sector performance from the stakeholders’ perspective. Thus, the supreme audit institutions (SAIs) through their performance auditing, deliver to stakeholders a credible assurance on the proper management of public resources.

SAIs were subject to many research papers during the last decades due to their importance in guaranteeing the correctitude of public money spending. The area of research varies from involvement in diminishing corruption levels [1,2,3], to the evaluation of the economic impact of SAIs [4] and to the transparency [5] and communication with the stakeholders (especially citizens) through social media [6].

SAIs contribution is decisive for the quality and efficiency of public financial management of each country [7]. The importance of SAIs for public sector reform is also emphasized by other authors, due to their surveillance role in the proper use of public resources and in guaranteeing accountability [8].

Also, SAIs have the ability to augment the responsibility of state authorities towards the citizens both for the used resources and the performance results [9].

In Romania, a former communist country till 1989, performance auditing has de-veloped during the last decade, although the SAI, denominated as the Romanian Court of Accounts (abbreviated RCoA), is over 150 years old. The inclusion of performance auditing in 2008, in the portfolio of specific activities for the RCoA was the consequence of Romania’s becoming a European Union full member state since 2007.

The retrospective normative research of Romanian performance auditing reveals a significant dynamic of legal regulations, due to Romania’s EU integration and the RCoA rallying efforts to the SAIs international model promoted by the International Organization of Supreme Audit Institutions (INTOSAI). Consequently, the dynamic of revising and updating the Romanian regulations follows mainly the international influence and knowledge [10,11].

Romanian regulations on performance audit have been developed based on the International Standards of Supreme Audit Institutions (ISSAI). The objective of these stand-ards is to provide homogeneity and credibility of external audits in public sector. In this respect, the standards deal with issues concerning the quality of audit missions, the consolidation of audit reports credibility for users, improvement of audit process transparency, auditors’ responsibility towards other involved parties, definition of audit missions’ typology and and the related set of concepts.

The INTOSAI standards encourage SAIs to acknowledge the value they provide through their specific activities and to demonstrate it to citizens, Parliament and other stakeholders [12]. Moreover, ISSAI are under a periodic revising process, which contributes to transparency and allows stakeholders to be involved in the issuing process. On the other hand, the purpose of using ISSAI is to maintain high quality control measures for ensuring accountability and transparency [13].

Since the EU normative framework does not provide guidance regarding the auditing standards applied by the Member States’ SAIs, we witness different audit standard-setting approaches. While some EU SAIs enforced ISSAI based standards, others used International Standards of Auditing (ISA) or a combination of ISSAI and ISA as a reference or developed their own standards [14].

SAI have an important role in ensuring public sector accountability, their main activi-ties consisting in auditing public entities’ periodic reports, assessing the degree of conformity, advisory missions for Parliament’s commissions as well as performance audits [12]. Also, SAI deliver to the legislative and executive powers an independent analysis on public finance management as well as on implementing the public policies by public administration, thus contributing to the continuous improvement of establishing and implementing public policies [15].

As to the ISSAI adoption by SAIs, this is not mandatory and it involves voluntary adoption and conformity in order to improve the audit practices [16].

According to the Romanian regulations in the field [17], performance auditing represents an audit of good financial management, its coordinates being as follows: the evaluation of economies obtained in managing the allocated funds for performing the audited activity, that is the measurement of how management principles and practices ensure the diminishing of allocated resources’ costs without compromising the purposes’ achievement; the efficiency of using human, material, financial resources, including the examination of performance indicators system disclosure, of the internal control system and the procedures followed by the audited entities, that is the maximization of an activity’s results in relationship with the consumed resources and the report between the achieved results and the cost of resources involved; the effectiveness of using public funds, respectively the establishment of the degree of declared objectives’ fulfillment for an activity, as well as the comparison between the effective impact and the desired one.

The conceptual equation of performance audit includes three elements: economy, efficiency and effectiveness. Economy represents the minimization of allocated resources’ cost for achieving the estimated results of an activity or public entity with the maintenance of the according quality of these results. Efficiency consists of maximizing the results of an activity or of a public entity in relationship with the used resources for obtaining those results. Effectiveness represents the degree of achievement of programmed objectives for each of the activities and the relationship between the projected effect and the effective results of that activity [17].

Literature review provides multiple aspects on the conceptual approaches over per-formance auditing. Public sector performance auditing has a significant role in evaluating the governmental responsibility, through the monitoring of public power functioning and, most important, the use of public resources [18].

The effectiveness of performance audits conducted by Latin America’ SAIs was studied, revealing that the recommendations formulated by auditors generated changes in the auditees’ management and that the follow-up periodical missions represent a stimulus for improving performance audits’ effectiveness [19]. Under the same perspective, studies developed for the regional and the national SAIs in EU have disclosed two directions for the impact of performance auditing’ recommendations, that is the Anglo-American perspective and the Germanic one. The Anglo-American perspective is based on the actions of the audited entities and the monitoring processes, while the Germanic one is based on the Parliament’ reaction [20]. In Estonia, performance audits are considered useful even if they do not generate specific changes of organizational policies and practices, and the adoption of the audit’ recommendations is more probable when parliamentaries pay significant attention to this type of audit and when mass-media’ involvement leads to politicial debates [21]. In Belgium, studies performed on public administration revealed that although performance audits have not led to significant changes in auditees’ organizational pattern, however auditors’ intervention was visible more at the conceptual level, than at the strategic or instrumental one [22].

Another study that questions the influence SAIs’ performance audits have on public policies reveals that when performance audits generate debates, the influence of SAI’s opinions depends mainly on how the auditors argue their findings [23].

In Romania, the quite recent adoption of performance auditing concept is reflected in a scarcity of studies in the economic literature.

Considering the typology of the public external audit exercised by the SAIs in EU, the results of studies performed revealed several aspects: the standard audit typology (financial audit—performance audit—compliance audit and/or combined audits) is specific for 52% of the SAIs in EU, respectively from Belgium, Croatia, Denmark, Estonia, France, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia and Hungary; 30% of the SAIs in EU, respectively from Romania, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Finland, Germany, Greece, Malta and Spain perform more types of audits than the standard typology (specific audits or special investigations, technical, environmental, tax and budget policy, selective, horizontal audits, exploration studies, follow-up audits, general or management audits, real-time audits, ex ante and ex post audits, pre-contractual audits, IT audits as well as European funds auditing); 18% of the SAIs in EU (Austria, Ireland, Luxemburg, Sweden and The Netherlands) perform a more narrow typology of missions reported to the standard one [24].

Also, the presence of performance audits in all the 27 SAIs from EU member states reveals the major importance given to the public sector approach in terms of the economy, efficiency and effectiveness [24]. Moreover, related to performance audit, a wide variety of audit practices was highlighted at the level of public entities of the European countries [25].

Public sector managers consider of major importance the performance auditing of RCoA argued by the added value on the activity of public institutions in terms of the use of resources and their performance. Through its objectives, the performance audit is shaped on the sensitive areas in public sector activities and its results provide a faithful image on economy, efficiency and effectiveness in managing public financial resources for achievement of the established purposes [26].

Considering the mobilization of significant financial resources in public sector entities and the existence of an information asymmetry between public sector managers and the stakeholders with respect to the use and management of public resources, performance auditing delivers to stakeholders an independent and a reliable assurance for the economic, efficient and effective use of public money and, consequently, of a good governance. Complementary, other studies emphasized the value added by internet facilities to the improvement of interactivity, transparency and the openness of public sector entities in order to promote new forms of accountability [27]. Also, transparency, respectively the online accessibility is a component of a transparent management and of good governance as well as an instrument focused on sustainability, value-added creator for stakeholders [28].

The purpose of this paper is two-dimensional. The first dimension of the research deals with the degree of harmonization of Romanian performance auditing regulations to ISSAI (ISSAI 300 and ISSAI 3000), for the period 2009–2022, respectively from the adoption of performance auditing, as specific activity for RCoA, to present. The second dimension of the research deals with the official website disclosure degree of performance auditing information by the RCoA in comparison to the other SAIs of the EU member states.

The paper complements the specialized literature as it addresses the performance audit in the public sector from a perspective that has not been addressed so far in Romania and it is also quite limited at the international level. The added value of the research must be addressed in relation to the importance of performance auditing activities in ensuring the sustainability of public sector entities. Moreover, we must emphasize that an adequately standardized performance audit approach among EU SAIs is paramount to ensuring a coherent institutional response to new and complex challenges, allowing stakeholders to properly assess the state’s response and its performance. The COVID-19 pandemic perfectly highlights the performance audit’s capacity to identify both weaknesses and best practices by performing in-depth, multidisciplinary assessments, thus providing stakeholders with valuable insights into the public management of resources aimed at addressing such pivotal challenges and its results.

2. The Research Methodology

The first dimension of the research, respectively analyzing the degree of harmonization between the Romanian performance audit regulatory framework and ISSAI, employs a comprehensive longitudinal study on a 12-year timespan (2009–2021 period), starting with the adoption and initial regulation of the performance audit as a specific activity performed by the Romanian Court of Accounts, as the supreme audit institution of Romania, until nowadays. The chosen research period is relevant to reflect the evolution of the performance audit in Romania and establish how the national regulatory framework was adapted accordingly.

Concerning the performance audit specific regulations in Romania envisaged by the research, we adopted an exhaustive temporal approach, as follows: Law no. 94/1992 on the organization and operation of the Romanian Court of Accounts, republished in 2009 [29]; Regulation on the organization and conduct of the Court of Accounts’ specific activities as well as on their follow-up (abbreviated RODAS), in force in 2009 [30]; RODAS in effect in 2011 [31]; Court of Accounts’ audit standards (since 2011) [17]; Performance audit manual (since 2013) [32]; Law no. 94/1992 on the organization and operation of the Romanian Court of Accounts, republished in 2014, with the subsequent amendments and additions [33]; RODAS published in 2014 and its subsequent modifications [34].

The analysis is accomplished by reference to the specific matters comprised in ISSAI 300 Performance Audit Principles and ISSAI 3000 Performance Audit Standard, as generally accepted international benchmarks standards on performance audit, as a specific Supreme Audit Institutions’ engagement [35,36].

The first phase in researching the harmonization degree consists of identifying each envisaged standard’s provisions in order to be compared with the provisions contained in the Romanian normative framework.

For ISSAI 300, the following criteria were selected: the definition of performance audit, the ways of providing added value through performance audit, the 3E definitions (economy, efficiency and effectiveness), the objectives of performance auditing, audit type overlaps (combined audits), the three parties involved in performane auditing, the subject matter and criteria, confidence and assurance.

Regarding the performance audit principles, as detailed in chapter 5 of ISSAI 300, the comparison considered both the ten general principles (audit objective, audit approach, criteria, audit risk, communication, skills, professional judgement and scepticism, quality control, materiality and documentation) and also the principles related to the audit process (planning—the selection of topics and the effective planning, conducting—evidence, findings and conclusions, reporting—the content of the report, recommendations, distribution of the report and also follow-up).

For ISSAI 3000, the selected research criteria are related to the 20 requirements (general and requirements related to the performance auditing process) and the subsequent explanations regarding independence and ethics, intended users and responsible parties, subject matter, confidence and assurance, audit objective(s), audit approach, audit criteria, audit risk, communication, skills, supervision, professional judgment and scepticism, quality control, materiality, documentation, selection of topics, designing the audit, conducting, reporting and follow-up.

Performing a content analysis on ISSAI and the Romanian SAI performance auditing regulations, the convergence between the two frameworks is analyzed through an association coefficient, respectively the similarity one. Accounting literature frequently uses the similarity coefficient to measure harmonization, as it offers relevant results [37]. Based on the criteria established in previous research papers, it can be argued that we conduct a formal harmonization study, as we considered only convergence between Romanian legal provisions in performance auditing and ISSAI and not the actual good practices in filling in the performance audit reports [38].

By recourse to the review of the previous research regarding formal harmonization [39,40,41], we established the harmonization evaluation methodology, resulting the scores to be utilized in the analysis, as presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The scores used to assess the degree of harmonisation between the Romanian regulations regarding the performance audit and ISSAI provisions (ISSAI 300 and ISSAI 3000).

The maximal score (1) was granted for either a full convergence and also if the national regulations are more detailed than the ISSAI provisions and use a similar approach, considering that a more detailed normative framework can facilitate the harmonization process.

A 0.7 score is specific to the Romanian regulations identified as incomplete compared to the ISSAI provisions, considering that a lack of details can hinder the performance audit normative harmonization with ISSAI.

A 0.3 score was granted to substantially divergent or incomplete national provisions correlated to ISSAI requirements.

Conversely, no score was granted if the Romanian regulations either do not encompass ISSAI specifications or offer a completely divergent approach.

We admit that the scores revealed above comprise a certain degree of researcher’s subjectivism when performing the text analysis, but this risk is inherent in this type of research.

For each temporal milestone (2009, 2011 and 2014 to date), the ISSAI 300 and ISSAI 3000 convergence scores were calculated by reporting the sum of the harmonization scores associated with the criteria, to the number of appraised criteria (25 criteria for ISSAI 300 and 20 criteria for ISSAI 3000). Subsequently, the general convergence score was determined as follows:

where:

- Gcs = general convergence score

- HSi = harmonization score for ISSAI 300 criteria

- n = number of ISSAI 300 appraised criteria

- HSj = harmonization score for ISSAI 3000 criteria

- m = number of ISSAI 3000 appraised criteria

The second research dimension, respectively the analysis of performance audit-related information degree of dissemination by RCoA compared to the other 26 supreme audit institutions (abbreviated SAI) pertaining to EU member states, is materialized in a quantitative research.

In this regard, firstly, we defined nine specific variables (related to performance audit, SAI legal framework, ISSAI, ISSAI 300, ISSAI 3000, the 3E and the performance audit report). Using the content analysis method on the 27 EU member state SAI’s websites, we utilized their search engines to identify relevant data/information/documents pertaining to each defined variable, scoring 1 where such relevant elements were found and 0 conversely. Certain search outputs were disconsidered as not being relevant to the SAI’s own activity (press briefings on international SAI gatherings, links to INTOSAI webpages), pinpointing the research on the disclosure of each SAI’s performance audit statutory framework and engagements. We employed the content analysis method both on the English version of the websites, as well as the respective official language [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68], using neural machine translation services in cases where the English version did not yield sufficient results to score a variable as 1. The data was collected manually until 31.01.2021 and was electronically centralised. Certain limitations arise from some websites not containing sufficient English content, thus making parts of the research dependent on the accurate translation of other official EU languages to score each variable adequately.

Subsequently, in order to evaluate the degree of dissemination of performance audit-specific information, we utilized the disclosure index (the information disclosure index), by comparing the information effectively disclosed to the total possible disclosure.

From a mathematical standpoint, the disclosure index is calculated using the following formula [69]:

where:

- DI = disclosure index;

- di = 1 if relevant information is identified, 0 conversely;

- m = the number of items actually disclosed;

- n = the maximum number of elements that can potentially be disclosed.

Consequently, the disclosure index can score between 0 and 1. Essentially, greater the value, the more performance audit-specific information was found to be disclosed on the websites managed by the EU27 SAIs.

The research will focus on three scientific research research questions (abbreviated RQ). RQ1: Has the Romanian SAI adopted in its normative framework the foremost ISSAI provisions on performance audit? RQ2: Has the harmonization degree with ISSAI provisions been systematically improved since introducing performance audit in Romania, correlative with the regulatory revisions? RQ3: To what extent is the RCoA disclosing performance auditing information in comparison to the other SAIs of the EU member states? The first two research questions will be addressed using the similarity coefficient and the third one using the disclosure index method.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Degree of Harmonization of Romanian Performance Auditing Regulations with ISSAI

The research employed a longitudinal study of the Romanian regulatory framework compared to the latest ISSAI 300 and ISSAI 3000 revisions as published on the INTOSAI website, as internationally accepted performance audit standards.

Employing the methodology described in Section 2, firstly, we analyzed the content of performance audit specific policies, as stated by the Romanian regulations and ISSAI 300. For a more in-depth harmonization analysis, we firstly addressed eight ISSAI 300 criteria regarding the performance audit framework and elements, as presented in Table 2, where the Romanian normative framework convergence score was initially 0.7125, subsequently improving to 0.8000 starting in 2011.

Table 2.

Harmonization between Romanian performance audit regulations and ISSAI 300 Performance audit framework and elements.

Subsequently, the research focused on the harmonization with the ISSAI 300 general principles of performance audit (ten criteria) and the specific principles related to the audit process (seven criteria), as presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Harmonization between Romanian performance audit regulations and ISSAI 300 Principles of performance audit.

The research results illustrate the Romanian framework has continually improved its approach to enforcing the general principles of performance audit, starting with a convergence score of 0.39 in 2009 and improving to 0.57 in 2011 and respectively to 0.78 presently. Meanwhile, the convergence score for audit process-related principles improved moderately, from 0.7143 in 2009 to 0.8143 in 2011 and 0.8714 presently.

Afterwards, the research focused on the harmonization with 20 criteria regarding ISSAI 3000, as presented in Table 4. The results highlight that the convergence score with ISSAI 3000 sistematically improved starting with 0.5250 in 2009 and improving to 0.7250 in 2011 and respectively to 0.8250 presently.

Table 4.

Harmonization between Romanian performance audit regulations and ISSAI 3000.

The research results illustrate that Romania follows a convergence process of its national regulations regarding the performance audit with ISSAI 300 and ISSAI 3000. Considering that this is an ongoing process, presently we cannot claim full conformity, but rather a harmonization with ISSAI with regard to transposing most of the significant ISSAI provisions into the Romanian regulatory framework, adapted to the national context, even more as the content analysis of the two references has often revealed different ways of expressing. Correlatively, the results pertaining to the general convergence score are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

General convergence score.

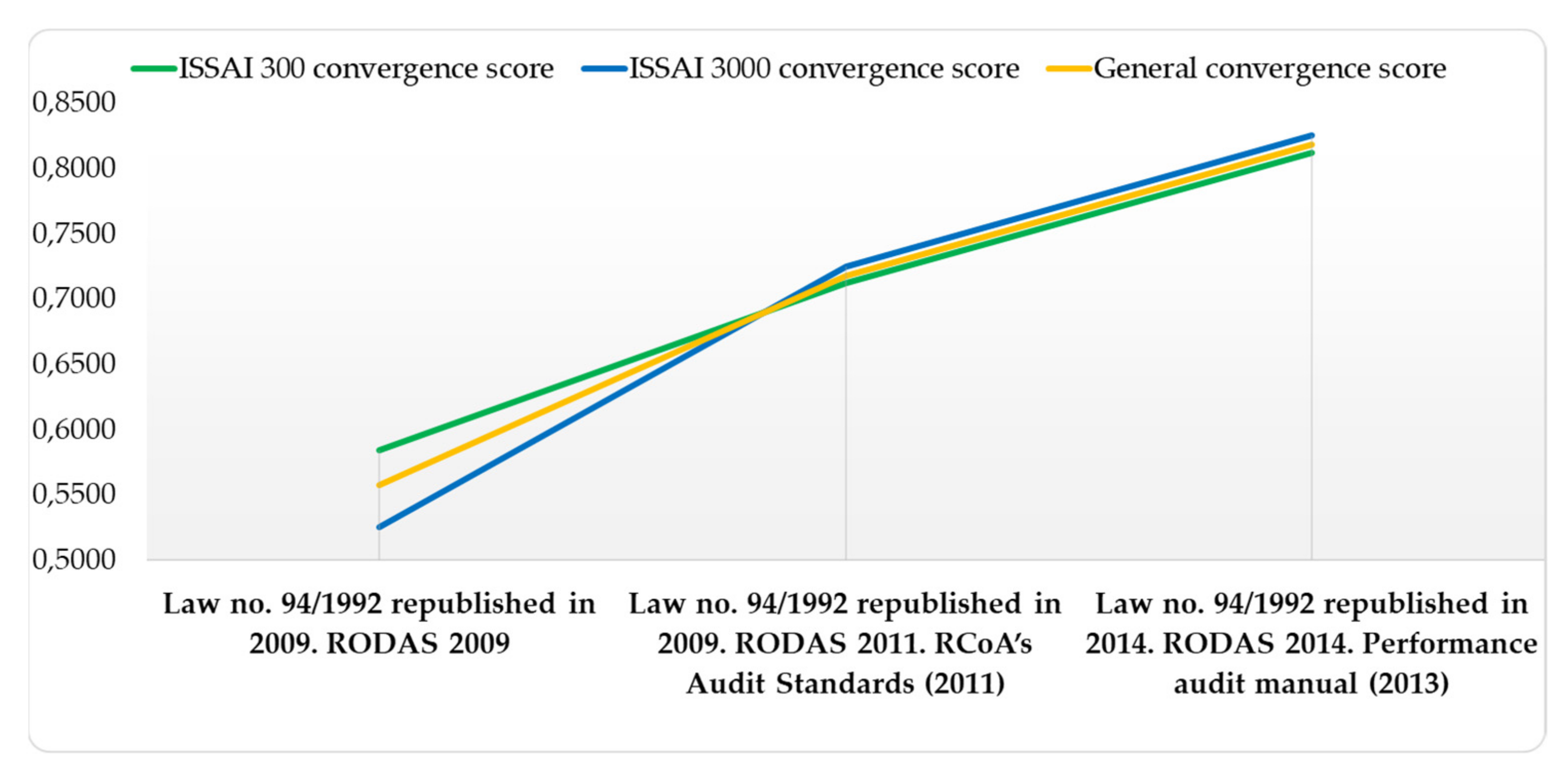

The harmonization scores indicate an overall convergence improvement between the national audit performance regulatory framework and INTOSAI standards (both ISSAI 300 and ISSAI 3000) during the analyzed period. The evolution of the harmonization level is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Convergence evolution of the national performance audit regulations with ISSAI.

In essence, since the adoption of performance auditing in Romania, the convergence score improved by 39% concerning ISSAI 300, respectively by 57% regarding ISSAI 3000, while the general convergence score improved by 47%.

The results obtained enable us to conclude that the Romanian regulations on performance audit transpose, by all significant aspects, ISSAI 300 provisions regarding the 3E definitions, objectives of performance auditing, subject matter and criteria, confidence and assurance, documentation, selection of topics, evidence, findings and conclusions, recommendations and ISSAI 3000 requirements regarding the audit objective(s), communication, supervision, documentation, selection of topics, designing and conducting the audit. All these criteria scored 1 over the entire analyzed timespan.

The research results illustrate a substantial convergence (minor differences between ISSAI provisions and the Romanian regulations) regarding the performance audit definition, the audit criteria and the performance audit report’s content. Dissimilar with ISSAI, the Romanian definition of performance audit does not encompass its objective and reliable attributes nor its contribution to identifying improvement opportunities. However, we are bound to point out that these attributes are promoted throughout the regulatory framework although not expressly mentioned in the national definition of performance audit. As for the audit criteria, ISSAI 300 and ISSAI 3000 provisions are transposed by all significant aspects in the national regulations, except for providing means of discussing the audit criteria with the auditee. While ISSAI suggests discussing the audit criteria with the auditee, underlining the auditor’s final responsibility for selecting suitable criteria, such an approach is not provided by the Romanian regulations. With regard to the performance audit report content, the Romanian regulations do not include reformulating the audit questions in order to adapt to the obtained evidence and to be able to provide suitable answers.

From a diametrically opposite perspective, absolute and perpetual divergences between the Romanian regulations on performance audit and ISSAI 300 were identified regarding combined audits. The national norms provide for conducting concomitant or consecutive performance and other audit engagements without detailing in any meaningful way the manner a combined mission can be planned, conducted, reported or followed-up. Also, absolute divergence was noted between the Romanian regulations and ISSAI 3000 regarding confidence and assurance. While the Romanian norms aim for high-quality performance audit reports, the auditor is not held to communicate such assurance in his report, allowing us to conclude that the Romanian regulations are eminently geared for quality control rather than quality assurance and communication.

Substantial divergence was highlighted between the ISSAI approach and the Romanian regulations regarding materialit since RODAS and RCoA’s own audit standards do not contain any mention of the specific concept of materiality in the performance audit. However, some clarifications in this regard are presented in the Performance Audit Manual, but the concept is not sufficiently detailed to ensure the transposition of the ISSAI 300 and ISSAI 3000 provisions.

In the light of the other criteria envisaged, the research results indicate an improvement over time in the harmonization degree.

The criteria for which the harmonization degree evolved over time from substantial divergence to substantial convergence, by mitigating the differences in approach between Romanian regulations and ISSAI, refer to the parties involved in performance auditing, audit risk, communication, skills, professional judgement and scepticism, reporting, the report dissemination and follow-up. With regard to the parties involved in performance audit, they are not yet expressly presented in the Romanian regulations, but are inferred from the content. The explicit nomination of the parties involved in the performance audit, in the Romanian regulations, would be useful in order to enhance their due importance.

Regarding the audit risk, we identified some difference in approach, since ISSAI 3000 refers to “audit risk” as pertaining to the performance audit report quality, based on the premise that audit evidence quality and the capacity to interpret them influences the risk of reaching incorrect or incomplete conclusions, impacting the audit report’s added value. Meanwhile, the Romanian regulations (RODAS and the Audit standards), except for the Performance audit manual, offer a risk interpretation closer to the financial audit and oriented predominantly on the audited entity/process/activity, and consequently, classify it as inherent and control risk. However, the performance audit manual offers a relatively adequate transposition of ISSAI 3000, thus filling the normative gap. It should be noted, however, that the manual also presents the risks mentioned by RODAS and the standards, respectively the audited entity-specific risks, that can impede the audited activity/program/project/process to reach its objectives. Consequently, the Romanian regulations recognize the importance of the audit risk, which is addressed in an exhaustive manner.

Concerning communication, ISSAI 300 provisions are adequately transposed by the Romanian regulations, except for obtaining stakeholders feedback ensuing the performance audit report publication. The national norms allow only for obtaining feedback from the auditee’s management (although this conduct was not regulated in 2009 or 2011) as part of the quality control mechanism. This is a reminiscence of RCoA’s institutional approach, oriented mainly towards communicating with public stakeholders and it should be addressed in future norm reviews taking into consideration obtaining feedback from a wider range of stakeholders.

With regard to auditors’ skills, ISSAI provisions are only partially implemented by the Romanian regulations, since, although acquiring and maintaining the necessary skills is implied, the national norms do not catalog the skills specific to performance auditing (research design, social science methods and investigation or evaluation techniques) nor the manner of acquiring them. Furthermore, the 2009 Romanian norms did not provide means for consulting external experts to complement the auditor’s expertise and acquire performance audit evidence. Also, on the subject of professional judgment and scepticism, the ISSAI provisions are partially translated by the Romanian norms because, although professional scepticism, objectivity and professional conduct are fully detailed, attributes such as innovative spirit, receptiveness to opinions and arguments, flexibility, curiosity and creativity are not detailed. The lack of such qualities can also generate a rigid professional reasoning, caught up in certain thought-outs, which in value-for-money audit is not desirable.

With regard to the reports’ dissemination, the Romanian performance audit reports are not directly and widely available to all stakeholders. The performance audit report is communicated to the auditee and transmitted to other public entities, the Government, the Parliament’s committees, either in full or summarized, via the RCoA’s specialized Department that oversees the audited domain. When such a Department centrally coordinates the performance audit engagement, the significant aspects enclosed in locally conducted audit reports are included in the central performance audit report and disseminated to its users. The performance audit manual stipulates the publication of formally approved reports on the Court’s website and subsequently presenting them in press briefings meant to increase transparency, confirm the Court’s independence and objectivity, and bolstering its prestige.

The Romanian audit standards do not include specific follow-up standards for performance audits. The procedural and methodological delimitations are prescribed in RODAS, and several orientations substantial convergent with ISSAI are presented in the Per-formance audit manual.

The criteria that have evolved over the analyzed period from absolute divergence to convergence, by harmonizing all the significant Romanian provisions with ISSAI requirements, are audit approach and quality control. The RCoA’s audit standards (2011) do not encompass the audit approach, but subsequently, the Performance audit manual (2013) transposes in all significant respects the respective ISSAI provisions. Regarding quality control, the 2009 Romanian regulations did not include such provisions for the audit engagements.

The criteria evolving from substantial divergence to convergence, by harmonizing all the significant Romanian regulations with ISSAI provisions, are ethics and independence requirements and subject matter. In the first case, the 2009 RODAS did not reference the ethics and independence requirements. Secondly, the Performance audit manual (2013) integrates the ISSAI 3000 approach, although the earlier national regulations did not fully reflect these provisions and do not refer to the sensitive nature of performance audit from a political standpoint when addressing government-prioritized public programs.

The criteria evolving from substantial convergence to full convergence, by harmonizing all the significant aspects of the Romanian regulations with ISSAI provisions and requirements, are the ways of providing added value through performance audit, the intended users and responsible parties and effective performance audit planning. Regarding the first two criteria, the initial substantial convergence score is associated with the 2009 norms, which did not expressly include taxpayers as performance audits stakeholders. Concerning the effective planning of performance audit engagements, the 2009 Romanian regulations did not provide for consulting external experts to complement the auditor’s expertise and acquire audit evidence.

Also, the research conducted on the basis of the content analysis of the two sources allowed us to ascertain that the Romanian performance audit manual (2013) boasts a higher harmonization degree with ISSAI provisions than the RCoA’s Audit standards (2011). Correlative, we must underline the fact that the RCoA’s Audit standards (2011) are already a decade old and have not been updated since publication, and as such, they cannot keep pace with ISSAI, which enjoy periodic reviews, as a strategic priority of INTOSAI.

By validating the first research dimension, we have demonstrated that the RCoA has adopted through its internal regulations the main coordinates of ISSAI on performance auditing and we have also highlighted the systematic increase in the harmonisation degree with ISSAI, related to the revision of the applicable regulations, from the adoption of the performance audit in Romania to date.

3.2. The Dissemination Degree of Performance Audit-Specific Information by the RCoA Compared to the Other Supreme Audit Institutions of the EU Member States

Correlatively, in the second research dimension, we considered useful and interesting to investigate the dissemination degree of performance audit-specific information (including the adopted and applied standards) by the RCoA compared to the other supreme audit institutions of the EU Member States.

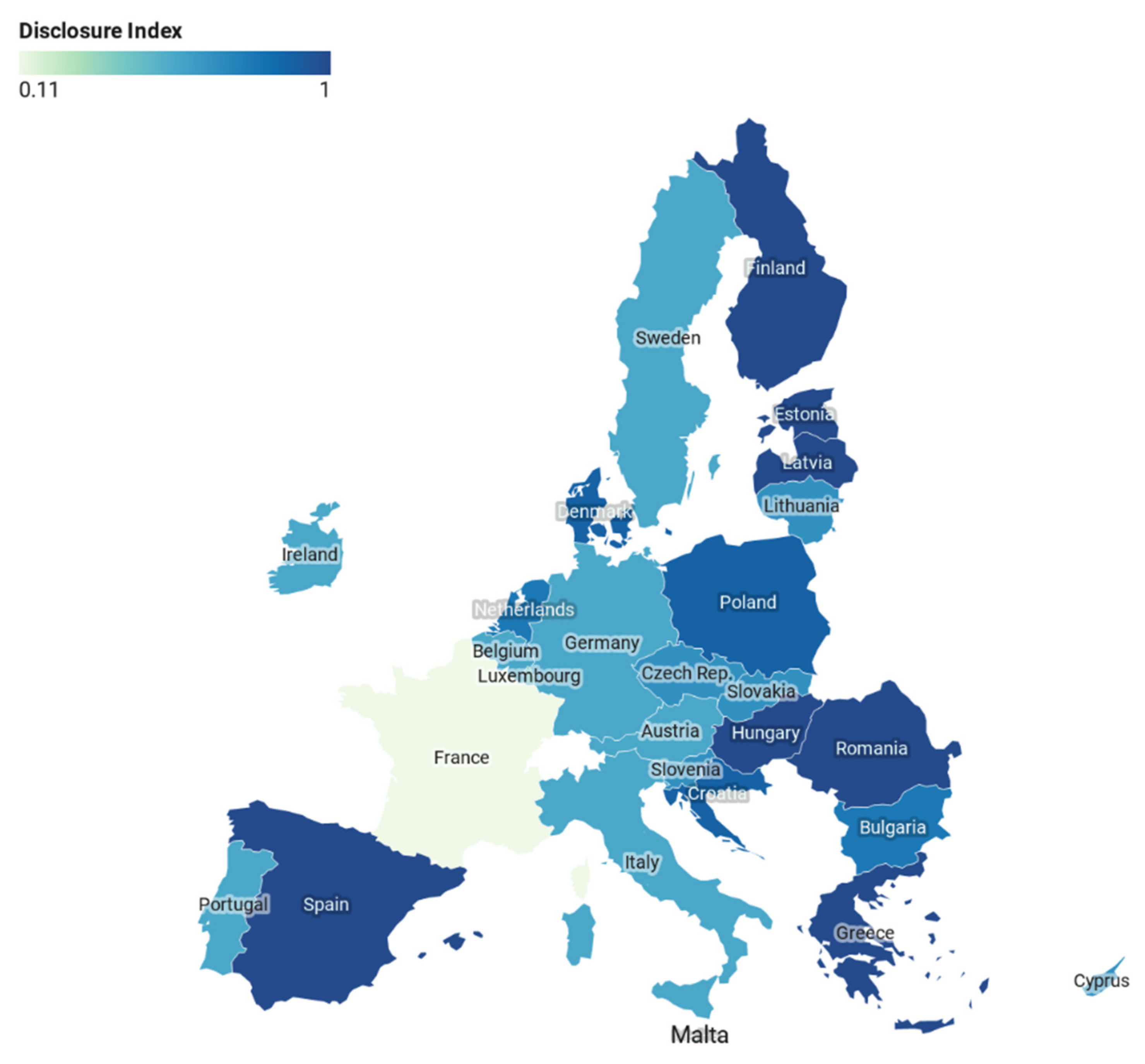

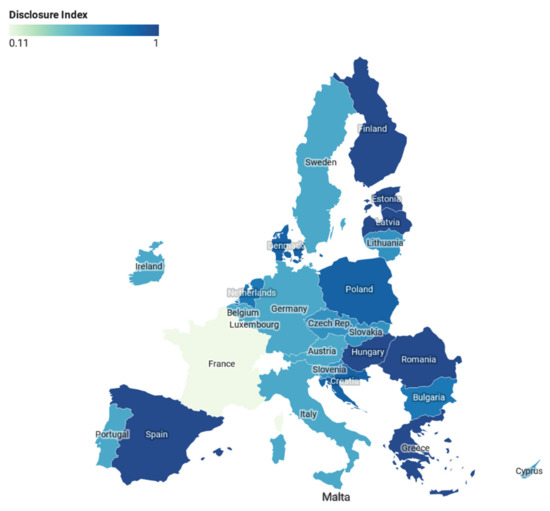

The disclosure index values, obtained through the official websites examination—both the English and the native language versions, employing their content analysis in correlation with the defined variables, are presented in Table 6 and transposed in Figure 2.

Table 6.

Disclosure Index.

Figure 2.

Disclosure index regarding performance audit at the level of the EU27 SAIs.

The research results emphasize significant differences between the SAIs belonging to the EU member states regarding the disclosure degree for performance audit-specific information. The Greek Court of Accounts is the only SAI for which the disclosure index could not be calculated, since its website does not offer search functionality.

The disclosure index for the rest of EU SAIs varies between 0.1111 (France) and 1 (Estonia, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Romania, Spain). Consequently, the French Court of accounts discloses the least performance audit-specific information. Conversely, the SAIs that offer all the analyzed information types are the National Audit Office of Estonia, the National Audit Office of Finland, the National Audit Office of Hungary, the National Audit Office of Latvia, the Romanian Court of Accounts and the Spanish Court of Accounts. The results are converging with those of the empirical research carried out by Garde-Sanchez et al. (2014) on using the official websites of the Spanish Court of Accounts and the Spanish Regional SAIs, in order to improve the transparency of their actions and the interaction with the stakeholders, revealing their efforts to provide relevant information on the management of public financial resources and highlighting a strong commitment of the Spanish SAI to the information disclosure practice towards transparency as a fundamental principle promoted by INTOSAI [70]. The research results illustrate that RCoA, as well as the majority of SAIs belonging to EU27 disclose information regarding the 3E—economy, efficiency and effectiveness (25 SAIs) and publish online their organic laws (23 SAIs). Also, as is the case with RCoA, 18 SAIs disclose information regarding the INTOSAI standards (ISSAI), while only 9 SAIs refer to ISSAI 300 Performance audit principles and 7 refer to ISSAI 3000 Performance audit standard. Only 12 SAIs disclose information regarding the performance audit reports, along with RCoA.

While RCoA’s disclosure index is 1, the mean value for disclosure index for the analyzed sample is 0.7222, suggesting that RCoa and EU member states’ SAIs manifest a high level of disclosure for performance audit-related information.

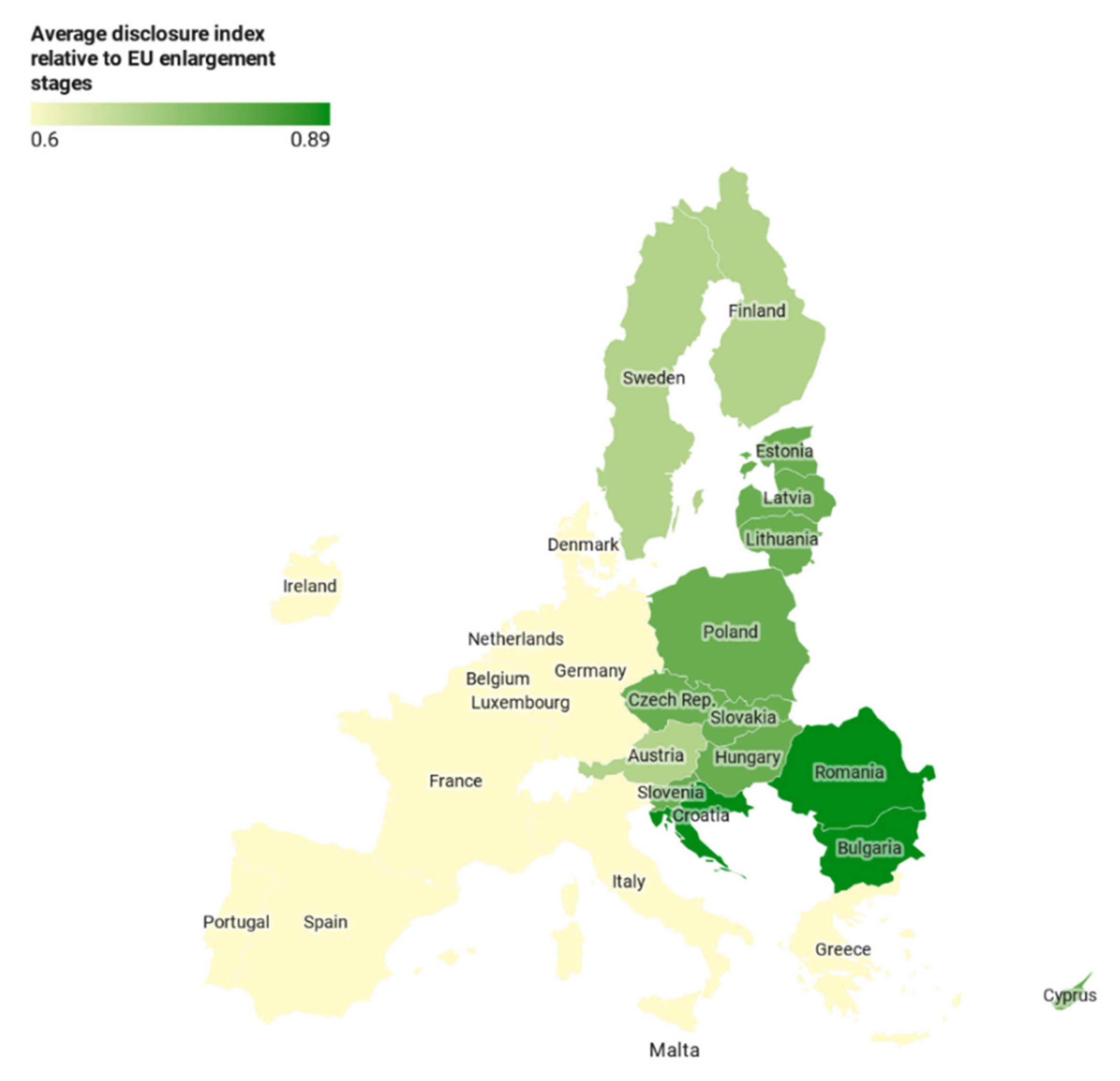

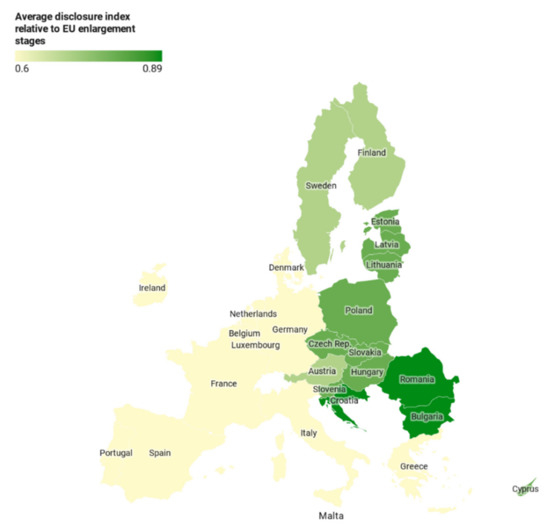

An interesting ascertainment arose when grouping SAIs by the year of each state’s gaining EU membership status (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The average disclosure index regarding performance audit, relative to the EU enlargement stages

By analyzing the grouping results, we can observe that the disclosure index for performance audit-related information increases proportionally to the EU enlargement stages (a 0.6000 mean for SAIs belonging to EU founding states, 0.7037 for SAIs of states composing to the 1995 enlargement, 0.8000 for member states’ SAIs that adhered in 2004, respectively 0.8889 for SAIs belonging to member states admitted in the latter enlargement stages—2007 and 2013). Altogether, SAIs from the states that were part of the latter stages of EU enlargement, as is the case with Romania, part of the 2007 EU enlargement, disclose significantly more performance audit-specific information compared to those with earlier membership status. From this standpoint, the results are convergent with those obtained by Matiş et al. (2014), confirming that the SAIs of states with latter EU membership manifest a greater interest in disclosing information to stakeholders and that the countries’ development does not significantly impact on the information presented by the SAIs. As previous research highlight, a possible explanation can be found in stricter membership adherence criteria for the latter stages of EU enlargement, enticing the candidate countries to disclose more information with respect to their SAIs activities [69].

From another perspective, the conducted research allowed us to conclude that, in most cases, the English version of SAIs’ websites offer little and sometimes outdated information compared to the native language version. In our opinion this reality is explained by the fact that the stakeholders for which the SAIs disseminate information come mainly from those countries, making the information presented in the national language more useful to them.

Also, the research results indicate a weak SAI inclination to present information regarding their performance audit standards. From this perspective, the research has highlighted two approaches, respectively publishing, on the websites, the ISSAI standards translated into native language (SAI Croatia, Estonia, Latvia, Poland, Slovenia, Hungary) or publishing their national standards in the native language (France, Czech Republic, Romania, Spain). The English version of the websites often present brief information regarding the audit standards adopted. SAIs have manifested little interest in publishing online their Performance audit manuals, only six instances of disclosure being identified (Estonia, Finland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia and Spain). The weak interest of the EU Member States’ SAIs in presenting the English version of their audit standards, as well as information related to processes and methods, has also been reflected by the research results of Matiş et al. (2014) [69].

With regard to performance audit reports, the SAIs that use their websites to publish individual performance reports, aggregated performance reports on each audit theme or summarized reports belong to states such as Bulgaria, Croatia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Romania, Spain, Sweden and Hungary.

4. Conclusions

The performance audit plays an essential role in ensuring the sustainability and the accountability of public sector entities. The performance audits’ importance is recognized within the European Union, since they are among the specific external public audit competences of the SAIs from all the 27 EU Member States, as an essential demarche to enhance the public sector performance, by improving the audited aspects and by monitoring the public power from “the 3E” perspective.

Correlated with the importance of performance auditing in the public sector, the paper provides interesting insights on it, revealing, on the one hand, the harmonization degree’s evolutionof the Romanian performance audit regulations with ISSAI (ISSAI 300 and ISSAI 3000), from the adoption and regulation of performance audit, as a specific activity of the RCoA, to date (period 2009 to 2021), and, on the other hand, the degree of performance audit information’ disclosure by the RCoA in comparison to the other SAIs in the EU Member States through their official websites.

In terms of the first research dimension, the results illustrate that Romania follows a convergence process of its national regulations with ISSAI 300 and ISSAI 3000. Considering that this is an ongoing process, presently we cannot claim full conformity, but rather a harmonization with ISSAI with regard to transposing most of the significant ISSAI provisions into the Romanian regulatory framework, adapted to the national context, even more as the content analysis of the two references has often revealed different ways of expressing. Therefore, the research results converge to the conclusion that the Romanian SAI has adopted through its internal norms, the main coordinates of ISSAI regarding performance audit.

The harmonization degree research has revealed a convergence improvement in time between the Romanian regulations on performance audit and INTOSAI standards (both ISSAI 300 and ISSAI 3000). In essence, since the adoption of performance auditing in Romania, the harmonization degree with ISSAI has systematically improved, in correlation with the national regulatory framework’s successive review.

Considering that disclosing rich information full of pragmatic potential regarding the public sector’s performance ensures transparency in relation to the stakeholders, in terms of the second research dimension, although the research results indicated variations in disclosing performance audit-related information between SAIs from different EU member states, the average disclosure index reflects a high degree of disclosure regarding performance audit-specific information between SAI’s belonging to EU27.

The results obtained from grouping SAIs by the state’s EU membership year highlight that states that were part of the latter stages of EU enlargement (including Romania) disclose significantly more performance audit-specific information compared to those with earlier membership status, and therefore tradition and prestige cannot serve as arguments against modernity and its drive to evolve and adapt to public sector performance requirements, as stringent needs of today’s society.

With respect to stakeholders’ information abundance for eminently native stakeholders that find the information presented in their national language the most useful, the research highlighted that, in most cases, the English version of SAIs’ websites offer little and sometimes outdated information compared to the native language version.

Furthermore, the research results reveal a weak SAI inclination to present information regarding their performance audit standards. From this perspective, the research highlighted two approaches used by SAIs, respectively publishing the INTOSAI standards (ISSAI) translated into native language on the website or publishing their national standards in the native language. SAIs have manifested little interest in publishing online their Performance audit manuals, only six instances of disclosure being identified among the EU27 SAIs.

Access to information regarding performance audit reports proved to be cumbersome. However, for the SAIs that disclose through their web-sites information in this respect, we have identified diverse practices, from publishing individual performance reports, aggregated performance reports on each audit theme or summarized reports.

Our research revealed heterogeneous practices regarding the disclosure of performance audit-specific information between SAIs belonging to EU27. This heterogeneity is stemming from a diversity of constitutional and legal mandates, the presence or absence of a jurisdictional function, their collegial or monocratic leadership and each country’s administrative heritage relative to public sector accountability, performance and transparency. All this diversity was expressed in an uneven approach to the availability of SAI’s audit standards and internal audit procedures, a somewhat lacking English language support, and a myriad of SAI’s webpage design and content.

In the light of current global challenges, we must stress the need to align EU performance audit practices regarding both conducting the audit and also disseminating its results to stakeholders.

The main research limitations refer to a series of language constraints, due to the fact that most websites offer detailed and exhaustive information only in the native language, and also to the analyzed websites’ heterogeneity, that present different information in different formats and for different timespans. Other research limitations are linked to the manual data collection and processing and a certain degree of researchers’ subjectivity when conducting content analysis, but this risk is inherent to this type of research.

In our opinion, it would be useful to establish express rules for disclosing performance audit-specific information inside the EU in order to attenuate the SAIs’ heterogenous approach in this field.

We consider the research results as relevant and useful both for the professional and the socio-economic environment, preoccupied with the specifics of public sector performance audit (stakeholders, decision factors, policymakers).

Public sector performance audit research is ample and thus future research directions envisage extending the harmonization analysis of national performance audit regulations with ISSAI for other EU member states, facilitating comparative studies among SAIs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-P.D. (T.-D.), I.C.P. and A.Ș.; methodology, C.-P.D. (T.-D.), I.C.P. and A.Ș.; software, C.-P.D. (T.-D.); validation, C.-P.D. (T.-D.), I.C.P. and A.Ș.; formal analysis, C.-P.D. (T.-D.); investigation, C.-P.D. (T.-D.); resources, C.-P.D. (T.-D.), I.C.P. and A.Ș.; data curation, C.-P.D. (T.-D.); writing—original draft preparation, C.-P.D. (T.-D.), I.C.P. and A.Ș.; writing—review and editing, C.-P.D. (T.-D.); visualization, C.-P.D. (T.-D.) and I.C.P.; supervision, A.Ș.; project administration, C.-P.D. (T.-D.); All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Reichborn-Kjennerud, K.; González-Díaz, B.; Bracci, E.; Carrington, T.; Hathaway, J.; Jeppesen, K.K.; Steccolini, I. Sais work against corruption in Scandinavian, South-European and African countries: An institutional analysis. Br. Account. Rev. 2019, 51, 100842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeppesen, K.K. The role of auditing in the fight against corruption. Br. Account. Rev. 2019, 51, 100798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Lin, B. Government auditing and corruption control: Evidence from China’s provincial panel data. China J. Account. Res. 2012, 5, 163–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume, L.; Voigt, S. Supreme Audit Institutions: Supremely Superfluous? A Cross Country Assessment. SSRN Electron. J. 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Bolívar, M.P.; Navarro Galera, A.; Alcaide Munoz, L. Governance, transparency and accountability: An international comparison. J. Policy Modeling 2015, 37, 136–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, L.; Royo, S.; Garcia-Rayado, J. Social media adoption by Audit Institutions. A comparative analysis of Europe and the United States. Gov. Inf. Q. 2020, 37, 101433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontogeorga, G.N. Juggling between ex-ante and ex-post audit in Greece: A difficult transition to a new era. Int. J. Audit. 2018, 23, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonollo, E. Measuring supreme audit institutions’ outcomes: Current literature and future insights. Public Money Manag. 2019, 39, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slobodyanik, Y.; Chyzhevska, L. The Contribution of Supreme Audit Institutions to Good Governance and Sustainable Development: The Case of Ukraine. Ekonomista 2019, 4, 472–486. [Google Scholar]

- Bostan, I. Metamorfoze instituționale privind exercitarea auditului public extern în România. Econ. Teor. Apl. 2011, 12, 32–41. [Google Scholar]

- Trincu-Drăgușin, C.P. Retrospective and topicality regarding the institutional organization and the role of the external public audit in Romania. Ecoforum J. 2020, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Cordery, C.J.; Hay, D. Supreme audit institutions and public value: Demonstrating relevance. Financ. Account. Manag. 2019, 35, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slobodianyk, Y.; Shymon, S.; Adam, V. Compliance auditing in public administration: Ukrainian perspectives. Balt. J. Econ. Stud. 2019, 4, 320–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, F.M.; Brusca, I.; Condor, V. In the pursuit of harmonization: Comparing the audit systems of European local governments. Public Money Manag. 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansons, E.; Rivza, B. Legal aspects of the supreme audit institutions in the Baltic Sea region. Res. Rural. Dev. 2017, 2, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenninkmeijer, A.; Moonen, G.; Debets, R.; Hock, B. Auditing Standards and the Accountability of the European Court of Auditors (ECA). Utrecht Law Rev. 2018, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanian Court of Accounts. Partea a III-a. Standardele specifice auditului performanței. Stand. Audit. 2011, 44–60. [Google Scholar]

- Umor, S.; Zakaria, Z.; Sulaiman, N.A. Follow-up Audit as an Accountability Mechanism of Public Sector Performance Auditing. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Accounting Studies (ICAS), Kedah, Malaysia, 15–18 August 2016; pp. 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Yetano, A.; Torres, L.; Castillejos-Suastegui, B. Are Latin American performance audits leading to changes? Int. J. Audit. 2019, 23, 444–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, L.; Yetano, A.; Pina, V. Are Performance Audits Useful? A Comparison of EU Practices. Adm. Soc. 2016, 51, 431–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudla, R.; Taro, K.; Agu, C.; Douglas, J. The impact of performance audit on public sector organizations: The case of Estonia. Public Organ. Rev. 2016, 16, 217–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desmedt, E.; Morin, D.; Pattyn, V.; Brans, M. Impact of performance audit on the Administration: A Belgian study (2005–2010). Manag. Audit. J. 2017, 32, 251–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichborn-Kjennerud, K. Performance audit and the importance of the public debate. Evaluation 2014, 20, 368–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trincu-Dragusin, C.-P.; Stefanescu, A. The External Public Audit in the Member States of the European Union: Between Standard Typology and Diversity. Audit. Financiar 2020, 18, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brusca, I.; Caperchione, E.; Cohen, S.; Manes-Rossi, F. IPSAS, EPSAS and other challenges in European public sector ac-counting and auditing. In The Palgrave Handbook of Public Administration and Management in Europe; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2018; pp. 165–185. [Google Scholar]

- Ștefănescu, A.; Trincu-Drăgușin, C.P. Performance audit in the vision of public sector management. The case of Romania. J. Account. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2020, 19, 778–798. [Google Scholar]

- Bonsón, E.; Torres, L.; Royo, S.; Flores, F. Local egovernment 2.0: Social media and corporate transparency in municipalities. Gov. Inf. Q. 2012, 29, 123–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Arceiz, F.J.; Pérezgrueso, A.J.B.; Torres, M.P.R. Accessibility and transparency: Impact on social economy. Online Inf. Rev. 2017, 41, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parliament of Romania. Law no. 94/1992 on the Organization and Operation of the Romanian Court of Accounts; Romania, 2009; republished. [Google Scholar]

- Romanian Court of Accounts. Regulation on the Organization and Conduct of the Court of Accounts’ Specific Activities as well as on the Resulting Documents Follow-Up; Romanian Court of Accounts: Bucharest, Romania, 2009.

- Romanian Court of Accounts. Regulation on the Organization and Conduct of the Court of Accounts’ Specific Activities as well as on the Resulting Documents Follow-Up; Romanian Court of Accounts: Bucharest, Romania, 2011.

- Romanian Court of Accounts. Manualul Auditului Performanței; Curtea de Conturi: București, România, 2013.

- Parliament of Romania. Law no. 94/1992 on the organization and operation of the Romanian Court of Accounts; Parliament of Romania: Bucharest, Romania, 2014; republished, with the subsequent amendments and additions.

- Romanian Court of Accounts. Regulation on the Organization and Conduct of the Court of Accounts’ Specific Activities as well as on the Resulting Documents Follow-Up; Romanian Court of Accounts: Bucharest, Romania, 2014.

- ISSAI 300. Performance Audit Principles; ISSAI. 2019. Available online: https://www.issai.org/professional-pronouncements/?n=300-399 (accessed on 9 January 2021).

- ISSAI 3000. Performance Audit Standard; ISSAI. 2019. Available online: https://www.issai.org/professional-pronouncements/?n=3000-3899 (accessed on 9 January 2021).

- Fontes, A.; Rodrigues, L.L.; Craig, R. Measuring convergence of National Accounting Standards with International Financial Reporting Standards. Account. Forum 2005, 29, 415–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Tas, L.G. Measuring Harmonisation of Financial Reporting Practice. Account. Bus. Res. 1988, 18, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Smith, J.V.D.L. Chinese GAAP and IFRS: An analysis of the convergence process. J. Int. Account. Audit. Tax. 2010, 19, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albu, N.; Pălărie, I. Convergence of Romanian accounting regulations with IFRS. A longitudinal analysis. Audit. Financ. 2016, 14, 634–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buculescu (Costică), M.M.; Velicescu, B.N. An analysis of the convergence level of tangible assets (PPE) according to Romanian national accounting regulation and IFRS for SMEs. Account. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2014, 13, 774–799. [Google Scholar]

- SAI Austria. Available online: www.rechnungshof.gv.at (accessed on 7 January 2021).

- SAI Belgium. Available online: www.ccrek.be (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- SAI Bulgaria. Available online: www.bulnao.government.bg (accessed on 9 January 2021).

- SAI Croatia. Available online: www.revizija.hr (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- SAI Cyprus. Available online: www.audit.gov.cy (accessed on 11 January 2021).

- SAI Czech Republic. Available online: www.nku.cz (accessed on 12 January 2021).

- SAI Denmark. Available online: www.rigsrevisionen.dk (accessed on 13 January 2021).

- SAI Estonia. Available online: www.riigikontroll.ee (accessed on 14 January 2021).

- SAI Finland. Available online: www.vtv.fi (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- SAI France. Available online: www.ccomptes.fr (accessed on 16 January 2021).

- SAI Germany. Available online: www.bundesrechnungshof.de (accessed on 17 January 2021).

- SAI Greece. Available online: www.elsyn.gr (accessed on 18 January 2021).

- SAI Hungary. Available online: www.asz.hu (accessed on 19 January 2021).

- SAI Ireland. Available online: www.audgen.gov.ie (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- SAI Italy. Available online: www.corteconti.it (accessed on 21 January 2021).

- SAI Latvia. Available online: https://lrvk.gov.lv/lv (accessed on 22 January 2021).

- SAI Lithuania. Available online: www.vkontrole.lt (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- SAI Luxembourg. Available online: www.cour-des-comptes.public.lu (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- SAI Malta. Available online: www.nao.gov.mt (accessed on 23 January 2021).

- SAI Netherlands. Available online: https://english.rekenkamer.nl/ (accessed on 24 January 2021).

- SAI Poland. Available online: www.nik.gov.pl (accessed on 25 January 2021).

- SAI Portugal. Available online: www.tcontas.pt (accessed on 26 January 2021).

- SAI Romania. Available online: www.curteadeconturi.ro (accessed on 27 January 2021).

- SAI Slovakia. Available online: www.nku.gov.sk (accessed on 28 January 2021).

- SAI Slovenia. Available online: www.rs-rs.si (accessed on 29 January 2021).

- SAI Spain. Available online: www.tcu.es (accessed on 30 January 2021).

- SAI Sweden. Available online: www.riksrevisionen.se (accessed on 31 January 2021).

- Matiș, D.; Gherai, D.S.; Vladu, A.B. A European Analysis Concerning the Compliance of Information Disclosed by Supreme Audit Institutions. Audit. Financ. 2014, 109, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Garde-Sanchez, R.; Rodriguez-Bolivar, M.P.; Alcaide-Munoz, L. Are Spanish SAIs Accomplishing INTOSAI’s Best Practices Code of Transparency and Accountability? Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2014, 43E, 122–145. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).