Building Relationships between Museums and Schools: Reggio Emilia as a Bridge to Educate Children about Heritage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Justification

3. Methodology

3.1. Literature Review

- Young children visit museum, n = 1,080,000;

- Young children museum spaces, n = 396,000;

- Artistic education for children, n =785,000;

- School museum collaboration, n = 880,000;

- School museum partnerships, n = 318,000;

- Educators’ museums training, n = 128,000;

- Early childhood education museum, n = 649,000;

- Reggio Emilia approach museum, n = 9300;

- Heritage education, n = 3,740,000;

- Heritage education primary school, n = 2,390,000;

- Knowledge construction Reggio Emilia, n = 23,200;

- Critical thinking reggio emilia, n = 19,400;

- Open education museums, n = 5160.

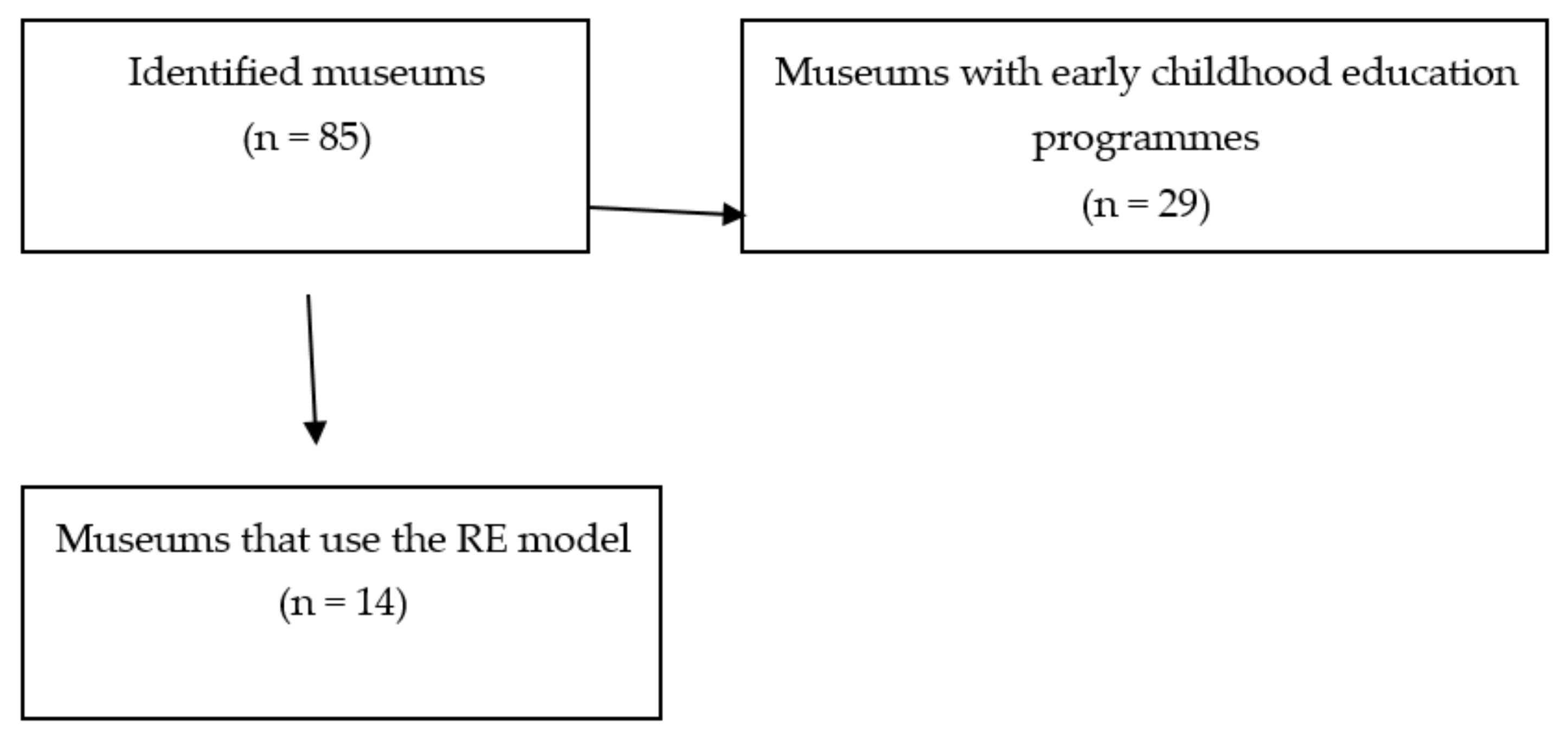

3.2. Analysis of the Practices of Museums

3.3. Expert Interviews

4. Literature Review

5. Results

5.1. Educational Practices of RE in Museums

5.2. Analysis of the Interviews with Experts

5.2.1. Relations between Schools and Museums

5.2.2. Relationships between Educators

5.2.3. Space Design

5.2.4. Types of Activities That Can Be Developed

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

7.1. Establishment of Museum–School Relations

- Provide spaces to design experiential experiences that arise from students’ interests about the world around them;

- Ensure that the activities connect the socioeducational reality of the students with the heritage history that is transmitted;

- Design activities that allow students to co-create, explore and express themselves;

- Favor the presence of artistic, plastic and interpretative actions in activities;

- Provide spaces for schools and museums to co-create adequate, innovative and up-to-date materials;

- Promote the co-designing of activities that can be worked both in school and in the museum instinctively;

- Open up spaces and round tables so educators can share educational methodologies;

- Ensure that the co-designed activities grant a leading role to the students;

- Ensure that the co-creation spaces for schools and museums design long-term projects to consolidate learning.

7.2. Design of Environments and Teaching Materials in Schools and Museums

- Create spaces and settings that excite and surprise students;

- Present materials that offer students opportunities to experiment, observe and investigate through projects that allow them to question things;

- Create an environment that allows children to develop their creative capacity without limits or restrictions;

- Use tools that promote the use of the different languages that the child can use during the early stage through proposals that facilitate the child’s expression;

- Develop digital guides in open formats to provide teachers with information on how to carry out activities, detailing the steps and materials to use;

- Open access to the museum’s contents in downloadable and printable formats so that teachers can use them in classroom activities;

7.3. Design of Activities That Promote the Development of Critical and Creative Thinking

- Adopt dialogic methodologies that allow situations for debate, discussion and assembly;

- Adopt the arts as a vehicle to enhance the cognitive development of the student through creative proposals;

- Promote projects based on problem solving that allow students to think critically;

- Provide experimentations and activities that allow the student to acquire autonomy and independence;

- Encourage teamwork to enable the exchange of points of view and dialogue among equals.

7.4. Establishment of Museum–Society Links

- Create exhibitions that allow sharing the child’s learning process with society;

- Collaborate and report periodically with families, making them participants in the students’ learning;

- Hold open workshops in museums so that children can experience the essence of the atelier.

7.5. Opening Pedagogies in Museums

- Implement cohesive open access and open education policies to freely access digitised content and educational guides that are generated around them;

- Develop strategic teaching plans oriented for different stages so that teachers of different subjects can use and adapt them;

- Implement pedagogical tables so that schoolteachers and museum educators can co-create pedagogic content;

- Invite teachers from outside the place where the museum is located to have virtual encounters and remote activities to bring together remote educational communities through the use of ICTs;

- Provide educational materials in different formats that are inclusive so that they are useful for different groups of students;

- Include digitised collections and teaching guides in education and open access portals such as Wikimedia Commons;

- Include clear information on the web pages about what educational proposals are offered by museums, including access to pedagogic materials and the type of open license associated with them.

7.6. Design of Pedagogic Activities at the University Level for Students in Museum, Heritage and Early Childhood Study Programmes

- Develop practical guidance for students to understand the role of the RE approach in creating bridges between schools and museums;

- Design experiential learning opportunities for students so they can visit schools and museums to understand how learning activities are designed;

- Invite students to explore and discover different school–museum educational programmes and examine their strengths and weaknesses;

- Organise cross-disciplinary round tables where the students can exchange ideas and experiences, documenting relevant practices;

- Invite museum and school educators to discuss with the students the curriculum design and the challenges faced by schools and museums;

- Design educational activities to teach students how to open up teaching and learning materials, supporting them in understanding the complexities of copyright and open licensing;

- Help students learn how to develop teaching plans and support different groups of learners in an inclusive way;

- Provide learning opportunities for students to learn how to co-create and co-design pedagogic activities bridging museums and schools;

- Provide students with practical experience in developing policies and strategies to bridge school and museum pedagogic activities by reviewing existing ones to identify good practices for establishing relationships between schools and museums.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malaguzzi, L. La Educación Infantil en Reggio Emilia; Ediciones Octaedro: Barcelona, Spain, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rankin, B. Education as collaboration: Learning from and building on Dewey, Vygotsky, and Piaget. In First Steps toward Teaching the Reggio Way; Hendrick, J., Ed.; Prentice-Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1997; pp. 70–83. [Google Scholar]

- Sassalos, M. With Dr. Abigail. S. McNamee Fall Discovering Reggio Emilia, Building Connections between Art and Learning. 1999. Available online: http://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED456890 (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Bersaluce Díez, R. La Calidad Como Reto en las Escuelas de Educación Infantil al Inicio del s. XXI: Las Escuelas de Reggio Emilia, de Loris Malaguzzi, Como Modelo a Seguir en la Práctica Educativa. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Alicante, Alicante, Spain, 2008. Available online: https://rua.ua.es/dspace/bitstream/10045/11273/1/tesis_Rosario_Berasaluce.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Gonzalez-Sanz, M.; Feliu-Torruella, M. Educación Patrimonial e Identidad. El Papel de los Museos en la Generación de Cohesión Social y de Vínculos de Pertenencia a una Comunidad. Clío: History and History Teaching. 2015. Available online: http://clio.rediris.es/n41/articulos/gonzalezFeliu2015.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Filipini, T. The role of the pedagogista. In The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Approach-Advanced Reflections, 2nd ed.; Edwards, C., Gandini, L., Forman, Y.G., Eds.; Ablex Publishing Corporation: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1998; pp. 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Oken-Wright, P. Documentation: Both Mirror and Light. Innovations in Early Education: The International Reggio Exchange. 2001. Available online: https://www.reggioalliance.org/downloads/documentation:okenwright.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Kirk, E. A School Trip for Reggio Emilia: Enhancing Child-Led Creativity in Museums. In Creative Engagements with Children: International Perspectives and Contexts; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 133–141. [Google Scholar]

- Feliu-Torruella, M.; Torregrosa, L.J. Descubro, Descubren, Descubrimos Juntos. Aula de Infantil. 2015. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5195424 (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Merillas, O.F.; Etxeberria, A.I. Estrategias e instrumentos para la educación patrimonial en España. Educ. Siglo XXI 2015, 33, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merillas, O.F.; Ceballos, S.G.; Arias, B.; Arias, V.B. Assessing the Quality of Heritage Education Programs: Construction and Calibration of the Q-Edutage Scale. Rev. Psicodidáctica 2019, 24, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firlik, R. Can we adapt the philosophies and practices of Reggio Emilia, Italy, for use in American schools? J. Fam. Econ. Issues 1996, 23, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C. Partner, nurturer, and guide: The roles of the Reggio teacher in action. In The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Approach to Early Childhood Education; Edwards, C., Gandini, L., Forman, G., Eds.; Ablex: Norwood, NJ, USA, 1993; pp. 151–169. [Google Scholar]

- Feliu-Torruella, M. Metodologías de enseñanza y aprendizaje del arte en la Educación Primaria. Didáctica de las Cien-Cias Experimentales y Sociales 2011, 25, 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Cuenca López, J.M.; Martín-Marín, M.J. Manual para el desarrollo de proyectos educativos de museos. Educatio Siglo XXI 2015, 33, 347–350. [Google Scholar]

- Piscitelli, B.; Anderson, D. Young children’s Perspectives of Museum Settings and Experiences. Mus. Manag. Curatorship 2001, 19, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, D.; Piscitelli, B.; Weier, K.; Everett, M.; Tayler, C. Children’s Museum Experiences: Identifying Powerful Mediators of Learning. Curator Mus. J. 2002, 45, 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weier, K. Empowering Young Children in Art Museums: Letting them take the lead. Contemp. Issues Early Child. 2004, 5, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, M.J.; DesRochers, L.; Cavicchi, N.M. Progettazione and Documentation as Sociocultural Activities: Changing Communities of Practice. Theory Pract. 2007, 46, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beresaluce Díez, R. Las escuelas reggianas como modelo de calidad en la etapa de educación infantil. Aula Abierta 2009, 37, 123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Feliu-Torruella, M. Cómo Podemos Aprender el Arte en Educación Primaria? Traslademos las Obras de Arte al Aula!. Educación Artística: Revista de Investigación (EARI). 2011. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/descarga/articulo/4358396.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Blanco, M. Qué es la Filosofía Educativa Reggio Emilia? 2017. Available online: https://www.lacasitadeingles.com/single-post/ReggioEmilia (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Edwards, C. Fine Designs” from Italy: Montessori Education and the Reggio Approach. Faculty Publications, De-partment of Child, Youth, and Family Studies. 2003. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1019&context=famconfacpub (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Cutcher, A.L. Art Spoken Here: Reggio Emilia for the Big Kids. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2013, 32, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas, A.L.C. Implicaciones educativas de la teoría sociocultural de Vigotsky. Rev. Educ. 2011, 25, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrera, B.; Mazzarella, C. Vygotsky: Enfoque Sociocultural. Educere. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ474756 (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Jové Monclús, G.; Betrián Villas, E.; Ayuso, H.; Vicens, L. Proyecto Educ−Arte−Educa (r) t: Espacio Híbrido. Rev. Educ. 2012, 35, 177–196. Available online: https://repositori.udl.cat/handle/10459.1/56974EJ474756 (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Gomez Carrasco, C.; Pérez, R.A.R. Aprender a enseñar ciencias sociales con métodos de indagación. Los estudios de caso en la formación del profesorado. Rev. Docencia Univ. 2014, 12, 307–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veraksa, N.; Shiyan, O.; Shiyan, I.; Pramling, N.; Pramling-Samuelsson, I. Communication between teacher and child in early child education: Vygotskian theory and educational practice/La comunicación entre profesor y alumno en la educación infantil: La teoría vygotskiana y la práctica educativa. Infanc. Aprendiz. 2016, 39, 221–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez, J.E.; Ávila Ruiz, R.M.; Listán, M.F. Primary and secondary teachers’ conceptions about heritage and heritage education: A comparative analysis. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2008, 24, 2095–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacini-Ketchabaw, V.; Kind, S.; Kocher, L.L.M. Encounters with Materials in Early Childhood Education; Routledge India: New Delhi, India, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Potočnik, R. Effective approaches to heritage education: Raising awareness through fine art practice. Int. J. Educ. Through Art 2017, 13, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero, P.; Merillas, O.F.; García-Ceballos, S.; Rodríguez, M.M. Heritage Education in The Archaeological Sites. An Identity Approach in The Museum of Calatayud. Curator Mus. J. 2018, 61, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poce, A.; Agrusti, F.; Re, M.R. Heritage Education and Initial Teacher Training: An International Experience. 2018. Available online: https://www.learntechlib.org/p/184460/ (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Rodríguez, M.M.; Merillas, O.F. Dealing with heritage as curricular content in Spain’s Primary Education. Curric. J. 2020, 31, 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabajo-Rite, M.; Cuenca-López, J.M. Student Concepts after a Didactic Experiment in Heritage Education. Sustain. J. Rec. 2020, 12, 3046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, S.; Robinson, R.; Ankenman, K. Project Work with Diverse Students: Adapting Curriculum Based on the Reggio Emilia Approach. Child. Educ. 1995, 71, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresler, L. “Child Art,” “Fine Art,” and “Art for Children”: The Shaping of School Practice and Implications for Change. Arts Educ. Policy Rev. 1998, 100, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flutter, J. Teacher development and pupil voice. Curric. J. 2007, 18, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Adams, J.; Kisiel, J.; Dewitt, J. Examining the complexities of school-museum partnerships. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2010, 5, 685–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, V.; Mackie, L. Extending the constructs of active learning: Implications for teachers’ pedagogy and practice. Curric. J. 2011, 22, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrance, E.P. Rationale of the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking Ability. Torrance; White, F., Peacock, E., Eds.; The Council for Exceptional Children: Illinois, IL, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Runco, M.A.; Jaeger, G.J. The Standard Definition of Creativity. Creat. Res. J. 2012, 24, 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runco, M.; Acar, S.; Campbell, W.K.; Jaeger, G.; McCain, J.; Gentile, B. Comparisons of the Creative Class and Regional Creativity with Perceptions of Community Support and Community Barriers. Bus. Creat. Creat. Econ. 2016, 2, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandini, L. Fundamentals of the Reggio Emilia approach to early childhood education. Young Child. 1993, 49, 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Bredekamp, S. Reflections on Reggio Emilia. Young Child. 1993, 49, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Tarr, P. Aesthetic Codes in Early Childhood Classrooms: What Art Educators Can Learn from Reggio Emilia. Art Educ. 2001, 54, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New, R.S. Reggio Emilia As Cultural Activity Theory in Practice. Theory Prac. 2007, 46, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchi, V. Art and Creativity in Reggio Emilia: Exploring the Role and Potential of Ateliers in Early Childhood Education; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, J.H.; Dierking, L.D. Learning from Museums: Visitor Experiences and the Making of Meaning; Altamira Press: Lanham, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Allard, M.; Boucher, S.; Forest, L. The Museum and the School. 1994. Available online: http://mje.mcgill.ca/article/view/8169 (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Feliu-Torruella, M.; Triadó, A. Interactuando con Objetos y Maquetas. Iber: Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales, Geografía e Historia. 2011. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=3616666 (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Strong-Wilson, T.; Ellis, J. Children and Place: Reggio Emilia’s Environment as Third Teacher. Theory Into Prac. 2007, 46, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder-Yu, G. Documentation: Ideas and Applications from the Reggio Emilia Approach. Teach. Artist J. 2008, 6, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, G. Reggio Emilia—An Impossible Dream? Can. Child. 1998, 23, 4–10. [Google Scholar]

- Bennet, T. Reactions to Visiting the Infant-Toddler and Preschool Centers in Reggio Emilia, Italy. Early Research and Practice. 2001. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED453001.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Fraser, S. Authentic Childhood: Experiencing Reggio Emilia in the Classroom, 2nd ed.; Thomson Nelson: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Eckhoff, A.; Spearman, M. Rethink, Reimagine, Reinvent: The Reggio Emilia Approach to Incorporating Reclaimed Materials in Children’s Artworks. Art Educ. 2009, 62, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, L. What Can We Learn from Reggio Emilia? The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Approach—Advanced Reflections. 1993. Available online: https://www.theartofed.com/content/uploads/2015/05/What-We-Can-Learn-From-Reggio.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Loh, A. Reggio Emilia Approach. 2006. Available online: http://www.brainy-child.com/article/reggioemilia.shtml (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Swann, A.C. Children, Objects, and Relations: Constructivist Foundations in the Reggio Emilia Approach. Stud. Art Educ. 2008, 50, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, E.M.; Dicarlo, C.F.; Sheldon, K.L. Growing democratic citizenship competencies: Fostering social studies understandings through inquiry learning in the preschool garden. J. Soc. Stud. Res. 2019, 43, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C. Three Approaches from Europe: Waldorf, Montessori, and Reggio Emilia. Early Childhood Research & Practice. 2002. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED464766.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- McClure, M. Spectral Childhoods and Educational Consequences of Images of Children. Visual Arts Research. 2009. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20715506?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Torraco, R.J. Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2005, 4, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, M.T.; Da Silva, M.D.; De Carvalho, R. Integrative review: What is it? How to do it? Einstein 2010, 8, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, M.J.; Booth, A. A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Heal. Inf. Libr. J. 2009, 26, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesson, J.; Matheson, L.; Lacey, F.M. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rocco, T.S.; Plakhotnik, M.S. Literature Reviews, Conceptual Frameworks, and Theoretical Frameworks: Terms, Functions, and Distinctions. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2009, 8, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torraco, R.J. Writing Integrative Reviews of the Literature. Int. J. Adult Vocat. Educ. Technol. 2016, 7, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Martín, A.; Orduna-Malea, E.; López-Cózar, E.D. Coverage of highly-cited documents in Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus: A multidisciplinary comparison. Science 2018, 116, 2175–2188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santín, M.F.; Torruella, M.F. Reggio Emilia: An Essential Tool to Develop Critical Thinking in Early Childhood. J. New Approaches Educ. Res. 2017, 6, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Santín, M.; Feliu-Torruella, M. Developing critical thinking in early childhood through the philosophy of Reggio Emilia. Think. Ski. Creat. 2020, 37, 100686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, S.; DeLamatre, J.; Jones, J. Measuring the Impact of Museum-School Programs: Findings and Implications for Practice. J. Mus. Educ. 2007, 32, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobick, B.; Hornby, J. Practical Partnerships: Strengthening the Museum-School Relationship. J. Mus. Educ. 2013, 38, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca, L.G.; Gorospe, J.M.C.; de Aberasturi Apraiz, E.J.; Etxeberria, A.I. El modelo reflexivo en la formación de maestros y el pensamiento narrativo: Estudio de un caso de innovación educativa en el Practicum de Magisterio The reflexive model in teacher training and narrative thinking: A case study of educational innovation in the. Rev. Educ. 2009, 350, 493–505. [Google Scholar]

- Witmer, S.; Luke, J.; Adams, M. Exploring the potential of museum multiple-visit programs. Art Educ. 2000, 53, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barragree, C. Museum and Public School Partnerships: A Step-by-Step Guide for Creating Standards-Based Curriculum Materials in High School Social Studies. 2007. Available online: http://krex.k-state.edu/dspace/handle/2097/286 (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Kundu, R. A Collaborative Affair: The Building of Museum and School Partnerships. 2010. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.840.3376&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Witmer, S. A Neighborhood Partnership: Art Around the Corner. Docent Educ. 2000, 10, 1. Available online: http://www.museum-ed.org/a-neighborhood-partnership-art-around-the-corner/ (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Elliot, J.R. The Infinity and Beyond: Museum-School Partnerships beyond the Field Trip. 2012. Available online: http://scholarship.shu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1217&context=theses (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Cuenca López, J.M.; Martín Cáceres, M.J.; Ibáñez Etxeberria, A.; Fontal Merillas, O. La Educación Patrimonial en Las Instituciones Patrimoniales Españolas: Situación Actual y Perspectivas de Futuro. 2014. Available online: http://rabida.uhu.es/dspace/handle/10272/12927 (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Fiore, A. The Reggio Emilia Approach to Early Childhood. Newsweek. 1991. Available online: https://tykesntotsdaycare.weebly.com/uploads/5/3/9/7/53974635/the_reggio_emilia_approach_to_early_childhood.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Hoyuelos, A. Reggio Emilia y la Pedagogía de Loris Malaguzzi. Revista Novedades Educativas. 2004. Available online: http://www.redsolare.com/new2/hoyuelos.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Forman, G.; Kuschner, D. The Child’s Construction of Knowledge: Piaget for Teaching Children; The National Association for the Education of Young Children: Washington, WA, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Forman, G. Different Media, Different Languages. Reflections on the Reggio Emilia approach. 1994. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED375932.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Burchenal, M.; Grohe, M. Thinking through Art: Transforming Museum Curriculum. J. Mus. Educ. 2007, 32, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingham, B. El Arte y el Patrimonio: Una nueva perspectiva en la educación. In Patrimonio e Identidad; Monasterio de Santa María La Real de Las Huelgas: Burgos, Spain, 2011; pp. 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Coll, C. Enseñar y aprender, construir y compartir: Procesos de aprendizaje y ayuda educativa. In Desarrollo, Aprendizaje y Enseñanza en la Educación Secundaria; Graó: Barcelona, Spain, 2010; pp. 31–62. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, C.; Gandini, L.; Forman, G. (Eds.) The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Approach to Early Childhood Education; Ables: Norwood, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.S.; Darling, L.F. Monet, Malaguzzi, and the Constructive Conversations of Preschoolers in a Reggio-Inspired Classroom. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2009, 37, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakil, S.; Freeman, R.; Swim, T.J. The Reggio Emilia Approach and Inclusive Early Childhood Programs. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2003, 30, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perret-Clermont, A.N. Social Interaction and Cognitive Development in Children; Academic Press: London, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Forman, G.; Fyfe, B. Negotiated learning through design, documentation and discourse. In The Hundred Languages of Children: The Reggio Emilia Approach-Advanced Reflections, 2nd ed.; Edwards, C., Gandini, L., Forman, Y.G., Eds.; Ablex Publishing Corporation: Greenwich, UK, 1998; pp. 239–260. [Google Scholar]

- Flavell, J.H. Cognitive Development: Children’s Knowledge about the Mind. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 1999, 50, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gimeno Sacristán, J.; Gómez, P. Comprender y Transformar la Enseñanza; Editorial Morata: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Quesada, A.; García, A.; Jiménez, J. Geografía e historia. In Profesores de Enseñanza Secundaria; Volumen Práctico; Editorial Mad: Madrid, Spain, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pindado, J. Las Posibilidades Educativas de los Videojuegos. Una Revisión de los Estudios más Significativos. 2005. Available online: https://idus.us.es/bitstream/handle/11441/45601/file_1.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Bagayogo, F.; Lapointe, L.; Ramaprasad, J.; Vedel, I. Co-creation of Knowledge in Healthcare: A Study of Social Media Usage. In Proceedings of the 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2014; pp. 626–635. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, B.L. Nursing education for critical thinking: An integrative review. J. Nurs. Educ. 1999, 38, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovi, A. Cheese, Children, and Container Cranes: Learning from Reggio Emilia. Daedalus 2001, 130, 105–118. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler, A. A Theory for Living: Walking with Reggio Emilia. Art Educ. 2004, 57, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelsson, I.P.; Sheridan, S.; Williams, P. Five preschool curricula—Comparative perspective. Int. J. Early Child. 2006, 38, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilman, S. Including the Child with Special Needs: Learning from Reggio Emilia. Theory Pract. 2007, 46, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bean, J.C. Engaging Ideas: The Professor’s Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom; John Wiley & Sons: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, C. Critical Thinking across the Curriculum: Process over Output. Int. J. Humanit. Social Sci. 2011, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Gokhale, A.A. Collaborative Learning and Critical Thinking. In Encyclopedia of the Sciences of Learning; Metzler, J.B., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 634–636. [Google Scholar]

- Fontal-Merillas, O. El patrimonio a través de la educación artística en la etapa de primaria. Arte Individ. Soc. 2016, 28, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. 2012 Paris OER Declaration. World OER Congress, Paris. June 2012. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/oer/paris-declaration (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- UNESCO. UNESCO Recommendation on OER. Paris: UNESCO Publications. 2020. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/themes/building-knowledge-societies/oer/recommendation (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Cronin, C. Openness and Praxis: Exploring the Use of Open Educational Practices in Higher Education. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2017, 18, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodeés, V. Una Teoriía Fundamentada sobre la Adopción de Repositorios y Recursos Educativos Abiertos en universidades lati-noamericanas. In Centro Internacional de Estudos de Doutoramento e Avanzados (CIEDUS), Programa de Doutoramento en Equidade e Innovación en Educación; Universidade de Santiago de Compostela: Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Havemann, L. Open in the Evening. In Open(ing) Education; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 329–344. [Google Scholar]

- Harley, D. Why understanding the use and users of open education matters. In Opening Up Education: The Collective Advancement of Education through Open Technology, Open Content, and Open Knowledge; The MIT Press: London, UK, 2008; pp. 197–211. [Google Scholar]

- Van Mourik Broekman, P.; Hall, G.; Byfield, T.; Hides, S.; Worthington, S. Open Education: A Study in Disruption; Rowman & Littlefield: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bayne, S.; Jandrić, P. From anthropocentric humanism to critical posthumanism in digital education. Knowl. Cult. 2017, 5, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atenas, J.; Havemann, L.; Neumann, J.; Stefanelli, C. Open Education Policies: Guidelines for co-creation. Open Educ. Policy Lab. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.A. The History and Emergent Paradigm of Open Education. In Open Education and Education for Openness; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M.A.; Britez, R.G. (Eds.) Open Education and Education for Openness; Sense Publishers: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, R. Knowledge infrastructures and the inscrutability of openness in education. Learn. Media Technol. 2012, 40, 251–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista, S.S.; Balsamo, A. Understanding the distributed museum: Mapping the spaces of museology in contem-porary culture. In Museums and Higher Education Working Together; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Bayne, S.; Knox, J.; Ross, J. Open education: The need for a critical approach. Learn. Media Technol. 2015, 40, 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, G.E. Progressive Museum Practice: John Dewey and Democracy; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Truyen, F.; Colangelo, C.; Taes, S. What can Europeana Bring to Open Education? Enhancing European Higher Education “Opportunities and Impact of New Modes of Teaching”. 2016. Available online: https://lirias.kuleuven.be/1811113?limo=0 (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Daniela, L. Virtual Museums as Learning Agents. Sustain. J. Rec. 2020, 12, 2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B.L. Recent Changes in Museum Education with Regard to Museum-School Partnerships and Discipline-Based Art Education. 1997. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20715917 (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Jové Monclús, G.; Moroba, S.C.; Moli, H.A.; Plana, R.S. Experiencia de Arte y Educación. La Escuela va al Centro de Arte y el Centro de Arte va a la Escuela. In Los Museos en la Educación: La Formación de los Educadores: I Congreso Internacional: Actas, Ponencias y Comunicaciones. Fundación Colección Thyssen-Bornemisza. 2009. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6375396 (accessed on 24 March 2021).

- Super, C.M.; Harkness, S. The Developmental Niche: A Conceptualization at the Interface of Child and Culture. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 1986, 9, 545–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderoqui, S.; Pedersoli, C. La Educación en los Museos: De los Objetos a los Visitantes; Ediciones Paidós: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- González-Sanz, M.; Feliu-Torruella, M.; Cardona-Gómez, G. Las Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS) desde la perspectiva del educador patrimonial. DAFO del método en su aplicación práctica: Visual Thinking Strategies from the perspectives of museum educators’: A SWOT analysis of the method’s practical implementation. Rev. Educ. 2017, 375, 160–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Museum | Philosophy | Link (accessed on 24 March 2021) |

|---|---|---|

| The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art | The RE pedagogy is used in this museum with the aim of enveloping the user and entering into a natural connection with the artistic language. | https://www.carlemuseum.org/content/reggio-emilia-inspired-programs |

| Portland Children’s Museum | Starting from the basic principles of RE pedagogy, the educational project of this museum aims to give a fundamental role to boys and girls in the construction of their learning. | https://www.portlandcm.org/about-us/our-philosophy |

| Imagine Nation, A Museum Early Learning Center | Cooperation is the basis of the educational project of this facility, understood as a fundamental axis between life, adults and children. | https://www.imaginenation.org/reggio-emilia-philosophy1 |

| The Strong National Museum of Play | Again, cooperative work between students and teachers appears as the basis of the museum’s educational project in order to create projects and build the curriculum. | https://www.museumofplay.org/education/woodbury-school/reggio-emilia |

| The Children’s Museum of Southern Oregon | In this museum, it is assumed that children are explorers by nature and that the role of the adult is to facilitate this exploration. | https://www.kid-time.org/single-post/2017/06/16/Reggio-Montessori-and-Waldorf-Oh-My |

| Miami Children’s Museum | The principles of respect, responsibility and community govern the central idea of the educational project of this museum, also inspired by the pedagogy of RE. | https://www.miamichildrensmuseum.org/preschool/ |

| Museu de les Ciències de Barcelona | The principles of respect, responsibility and community govern the central idea of the educational project of this museum, also inspired by the pedagogy of RE. | https://edunat.museuciencies.cat/projectes/el-niu-de-ciencia/ |

| Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza | With its En Abierto project, it offers proposals for educational activities and actions aimed at schoolgirls and students to carry out in the museum or in the classroom. | https://www.educathyssen.org/profesores-estudiantes/abierto |

| Museo Universitario de Arte Contemporáneo (México) | From the museum, proposals are generated for the development of creative and critical skills through the approach of infants for the use of the languages of contemporary art. | https://muac.unam.mx/infantiles |

| Whitney Museum of American Art | This museum offers students proposals to generate critical discussions about art, think creatively and create jointly with contemporary artists, educators and peers. | https://whitney.org/Education/Teens |

| The Children’s Museum (Indianapolis) | The goal of this museum is to create learning experiences through the arts, sciences and humanities to transform the lives of children and families. | https://www.childrensmuseum.org/about/preschool |

| Children’s Museum of Richmond | Based on the RE philosophy, this museum offers activities that encourage children to discover their own answers through play for children between the ages of 18 months and 5 years. | https://www.childrensmuseumofrichmond.org/community/sprout-school/ |

| Bay Area Discovery Museum | Museum inspired by RE’s learning philosophy, basing its experiences on respect for children and their abilities. | https://bayareadiscoverymuseum.org/preschool/about-us/our-approach |

| Musei Civici Reggio Emilia | These museums aim to stimulate interpretation skills and personal reworking. | https://www.musei.re.it/il-museo-per-la-scuola/per-la-scuola/ |

| Museum | Philosophy (Montessori, Creative Curriculum, Inquiry and Constructivism, Experiential Learning and Visual Thinking Strategies) | Link (accessed on 24 March 2021) |

|---|---|---|

| Museum of Modern Art (Moma) | Visual Thinking Strategies | http://www.pz.harvard.edu/projects/momas-visual-thinking-curriculum-project |

| Fundació Joan Miró | Experiential Learning and Visual Thinking Strategies | https://www.fmirobcn.org/es/actividades/centres-educatius/educacion-infantil/27/el-mundo-de-miro |

| Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía | Experiential Learning | https://www.museoreinasofia.es/actividades/tablero-invisible-2018 |

| Caixaforum | Experiential Learning | https://educaixa.org/es/-/manos-a-la-obra |

| British Museum | Visual Thinking Strategies, Inquiry and Constructivism | https://www.britishmuseum.org/learn/schools/ages-3-6 |

| Museu Picasso de Barcelona | Visual Thinking Strategies | http://www.bcn.cat/museupicasso/es/educacion/el-museu-en-la-escuela.html |

| Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya | Visual Thinking Strategies, | https://www.museunacional.cat/es/escoles-tandem |

| Museo Larco | Inquiry and Constructivism, Visual Thinking Strategies, Experiential Learning | https://www.museolarco.org/educacion/visitas-escolares/?origin=71 |

| Van Gogh Museum | Creative Curriculum, Inquiry and Constructivism | https://www.vangoghmuseum.nl/nl/bezoek/schoolgroepen#basisscholen |

| Birmingham Museums | Montessori | https://www.birminghammuseums.org.uk/blog/posts/the-minibrum-museum-a-museum-completely-curated-by-children |

| Kansas Children’s Discovery Center | Montessori | https://kansasdiscovery.org/ |

| National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea | Creative Curriculum, Experiential Learning | http://www.mmca.go.kr/learn/introduce.do |

| Smithsonian Museum | Montessori, Inquiry and Constructivism | https://www.si.edu/SEEC |

| The J. Paul Getty Museum | Visual Thinking Strategies | https://www.getty.edu/education/teachers/professional_dev/creative_core/ |

| National Gallery of Art | Visual Thinking Strategies | https://www.nga.gov/education/teachers/art-around-the-corner.html |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Feliu-Torruella, M.; Fernández-Santín, M.; Atenas, J. Building Relationships between Museums and Schools: Reggio Emilia as a Bridge to Educate Children about Heritage. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3713. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073713

Feliu-Torruella M, Fernández-Santín M, Atenas J. Building Relationships between Museums and Schools: Reggio Emilia as a Bridge to Educate Children about Heritage. Sustainability. 2021; 13(7):3713. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073713

Chicago/Turabian StyleFeliu-Torruella, Maria, Mercè Fernández-Santín, and Javiera Atenas. 2021. "Building Relationships between Museums and Schools: Reggio Emilia as a Bridge to Educate Children about Heritage" Sustainability 13, no. 7: 3713. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073713

APA StyleFeliu-Torruella, M., Fernández-Santín, M., & Atenas, J. (2021). Building Relationships between Museums and Schools: Reggio Emilia as a Bridge to Educate Children about Heritage. Sustainability, 13(7), 3713. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073713