Abstract

Questions determine our fate as individuals and societies. Asking the right questions at the right time and in the right amount makes our choices and decisions meaningful. As human beings we all experience this from an early age. In education, in order to evaluate, learn and inform the growth of students, the professional development of teachers and the overall efficiency of the system, questions become an integral element of the complex, non-linear and social system at different levels. The purpose of this article is to investigate how performance assessment strategies play a role in the education system, and to understand how progressive performance assessments can be set up with sustainable thinking and designed in alignment with the United Nation’s (UN) Development Goals (SGDs) for a given context. To aid Qatar’s pursuit in transitioning from a resource-based economy to a knowledge-based one, this study aims to design and develop a proper performance assessment (PA) framework that is aligned with the SDGs and education goals (EGs) to help achieve social and human development as envisioned in Qatar’s national vision. This article: (i) presents a theoretical and qualitative analysis of PA practices in the Qatar Education System (QES); (ii) provides a comparative analysis among the best PA practices at the global level; and (iii) examines the methodology, conditions, and findings based on learning from: (a) the successful experiences of other countries, (b) documented analyses of local past experiences, (c) local stakeholders (through a qualitative investigation) in order to understand the needs, develop recommendations and design a tailored PA strategy. The results indicate that there are misalignments between the core educational components such as EGs and the assessment methods used to evaluate them. The analysis and findings reveal that the QES urgently needs to develop a PA strategy that is appropriate for its stakeholders to meet the EGs and enhance their sustainability competencies. Finally, this study proposes a PA framework for the QES to align its core elements with SDGs and EGs.

1. Introduction

An education system aligned with the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) can form and empower a society prepared with the knowledge, understanding, habits, skills, and tools that can enable them to comprehend and successfully meet the complex sustainability challenges. Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) is a recent concept. It was developed to systematically grow the next generation with sustainable thinking and living habits. ESD aims to grow future generations with comprehensive awareness and understanding of sustainability challenges and with the willingness and skills necessary to create the right social change that leads towards sustainable thinking and living [1,2]. Specifically, ESD enhances the development of knowledge and skills, promotes critical thinking and innovation, and emphasize the values, attitudes, and actions required for sustainable living patterns and a sustainable world. ESD also aims for balanced environmental development and supports social equity by enabling individuals and societies to make decisions to improve quality of life with little or no harm to the environment and the future society.

Today, the new concept of education literacy goes beyond writing, reading, arithmetic and root memorization; it aims for literacy on research and information, digital media and data; creativity and innovation; and critical systems and design thinking capacities. For this to be achieved, education goals should be concerned with: (1) gaining knowledge in fundamentals such as mathematics, science, language, geography and history; (2) gaining the right sets of skills such as soft skills (e.g., communication, teamwork), high-order skills (e.g., learning to learn, critical and analytical thinking), life and survival skills, and technical skills (e.g., programming); (3) building students’ capability and capacity to be able convert their knowledge and skills into activities and actions, (4) having students gain morals and values stemming from both universally accepted ethical and social values as well as local culture, history, traditions, beliefs and religions; and (5) encouraging students to have high order purposefulness that can direct their individual behaviors and attitudes by utilizing their knowledge, skills, capacity and values for higher purposes for individuals and their society, humanity, and the Earth [3,4,5]. Almost all countries now seek to coordinate their national visions with the SDGs [6], however, studies show a lack of focus on ESD, i.e., teaching individuals to be future-oriented with regards to sustainable development [5,7,8,9].

A performance assessment (PA) is essential for the overall health, effectiveness, sustainability, and continuous improvement of any system and its designed and targeted outcomes. When the system that is social and of a complex and non-linear nature, such as an education system (ES), performance assessment as a sub-system becomes even more challenging and controversial compared to technical systems. PA in education also attracts serious criticism and suspicion and is affected by conflicting demands from various stakeholders and their interests because of its interdependence with other system elements or members (such as teachers, parents, decision-makers and curriculum). The 21st century competencies (a set of expectations requiring national education systems to meet ever-changing technological, economic, environmental and social contexts) need to be measured using the right methods of assessment with a detailed strategy for implementation that examines the reality and includes procedures to ensure continuous improvement by using assessment results [10]. Using students’ PA data is considered as strong informative and supportive evidence for the evaluation and accountability of the entire education system as well as improving the educational outcomes continuously.

The state of Qatar has adopted SDGs into its national vision (QNV 2030) [3], national strategies [11,12], and ministerial and sectoral plans as well as its education strategy [5,13]. Still, education goals (EGs) of the Qatar Education System (QES) are not clear and not fully aligned with the SDGs in terms of the identification of the goals, implementation, monitoring and continuous improvement [5]. If students of today and the next generations of future society are not assessed timely and properly under EG and SDG guiding principles and outcomes, they cannot be expected to possess SDG-oriented thinking and behavior. To increase the possibility of successfully meeting the educational outcomes of achieving the QNV 2030 goals and meeting the long-term challenges of human development, in addition to responding to challenges and negative impacts of sudden events such as the 2017 Qatar blockade and the Covid-19 pandemic, there needs to be a clear, concrete, integral, detailed performance assessment strategy.

This study aims to develop a PA strategy framework and processes for QES (k-12, i.e., from kindergarten to the 12th grade), to align it with the sustainability competencies, SDGs and EGs. This work starts with an exploratory review of recent studies on ESD, education from a system perspective, and performance assessment best practices, models and educational issues in education. Then a qualitative approach is employed to answer the research questions and ensure the involvement of all stakeholders to identify improvement needs and collaboratively develop solution ideas for the current PA strategy in the QES. A comparison with the best practices of PA in select countries is also used as lessons for improving the current PA strategy in the QES by revealing the global challenges and potential for improvement areas for PA policies along with the educational components that can have a direct impact on assessment. Drawing on a previous preliminary study [5], the PA framework is further improved by proposing a detailed, holistic, integrated strategy with self-reflective validation through a qualitative study involving QES stakeholders. Therefore, this study proposes that asking the right questions at the right time and in the right amount will inform the education system and direct its main constituents, that is, students, towards sustainable thinking, living and SDGs.

The structure of this article is as follows: Section 2 describes the research methodology used for this study. Section 3 and Section 4 present the study results found by conducting a three-dimensional analysis that includes a theoretical analysis of assessment practices in the QES, a comparative analysis of assessment strategies among the highest performing countries, and a qualitative analysis of interviews conducted among the QES stakeholders. Section 5 offers a holistic performance assessment framework for the QES built on findings from this and previous studies, as well the cultural, political and regional context of the country and its population. This is followed by a discussion in Section 6 and finally a conclusion in Section 7.

2. Research Design

In order to fully understand the multidimensional factors that affect the implementation of performance assessment practices and their interaction with the other elements in the QES from the perspective of the SDGs and ESD, these factors must be examined in depth. This will be very helpful and instrumental in strategizing and tailoring proper PA policies for continuous long-term improvements. It would also be used to answer the formulated research questions of the present study:

- What are the potential system- and structure-related issues that might adversely be affecting the outcomes of the QES from the perspective of the contribution of PA practices to SDG and ESD? Where and how does performance assessment play a role in this system and its expected outcomes?

- What could be a tailored, relevant and progressive PA model and what is its potential impact on the QES to align with and contribute to the SDG and ESD, and outcome (student) achievements?

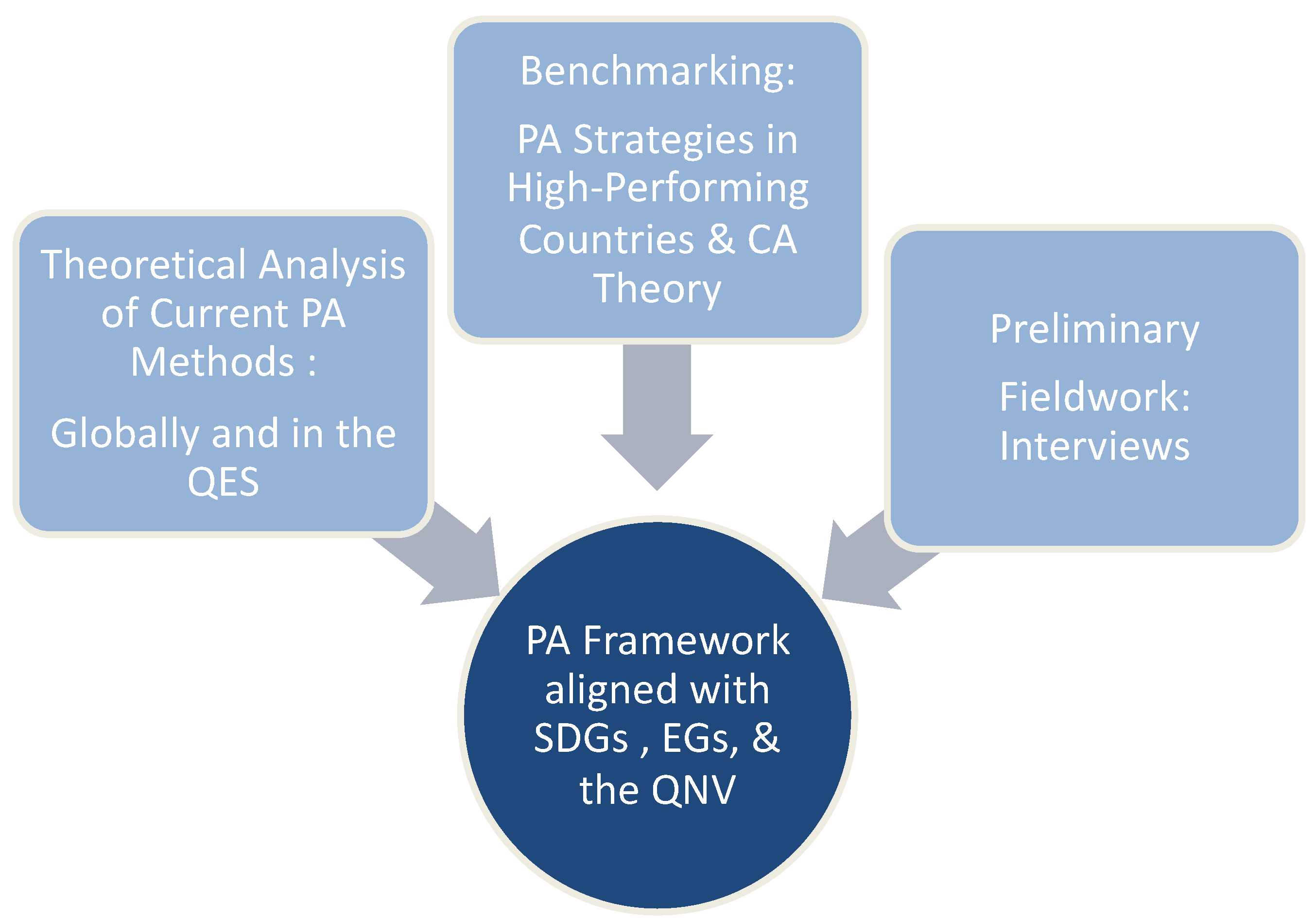

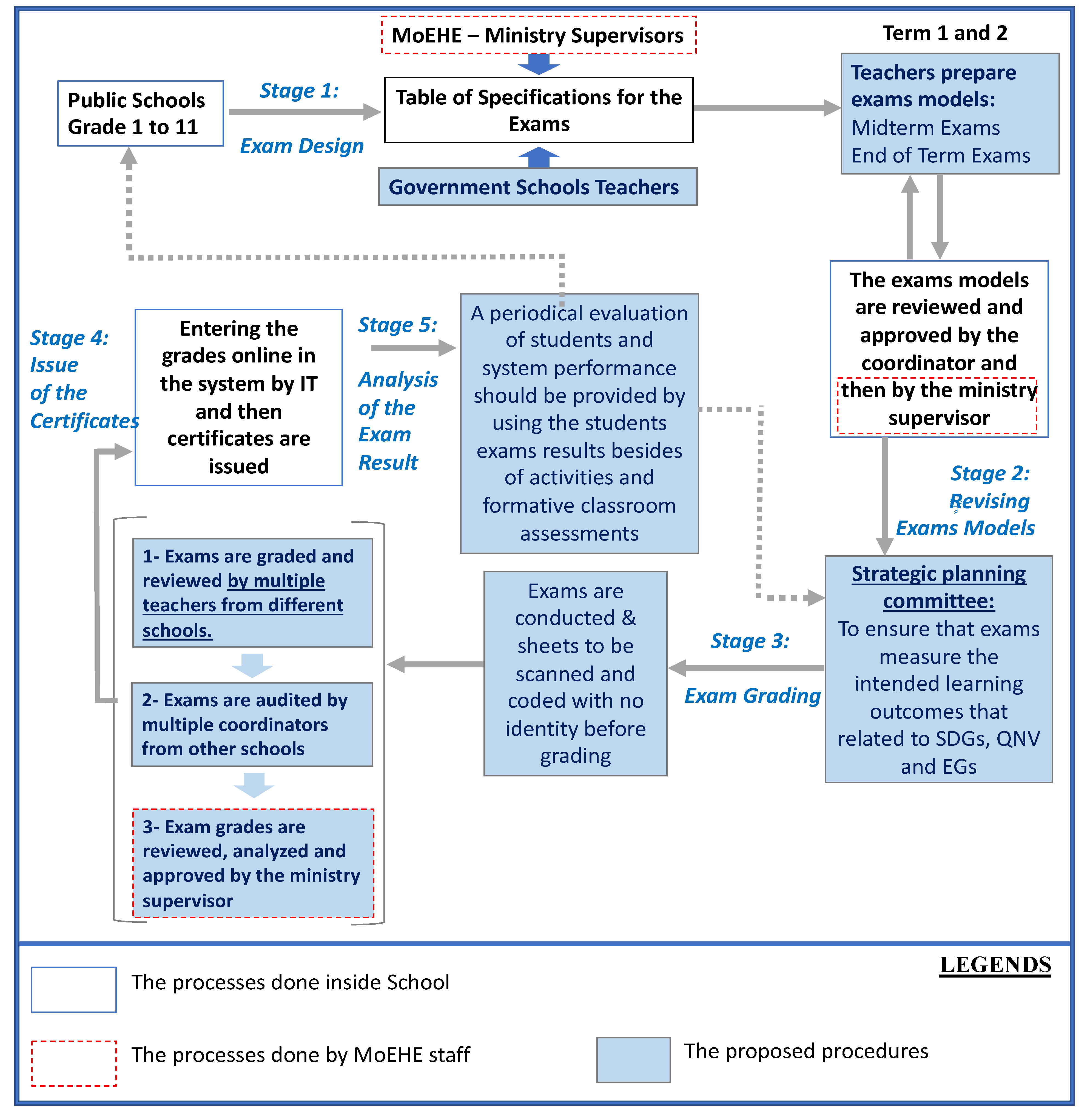

In this research, a tailored PA framework for the QES is developed based on a three-dimensional analysis that includes: (1) theoretical analysis of current PA practices in the QES, and (2) benchmarking with high-performing countries and education systems with a focus on PA strategies, and (3) qualitative analysis of interviews with the QES stakeholders to ensure a full understanding of challenges and to identify the local needs for improvement. To achieve the aims of this research, three well-connected steps were conducted, as represented in Figure 1. These steps were essential to have a clear direction for planning and shaping the assessment practices strategy and educational policies needed to achieve Qatar’s ideal education system.

Figure 1.

An illustration of the three-dimensional methodological tools to address the proposed performance assessment (PA) framework.

This research is based on a preliminary framework derived from both an extensive review of academic literature and the constructive alignment (CA) theory. This was developed in a previous study by the co-authors [5], where such a framework was proposed to be used in the evaluation and analysis of Qatar’s educational practices from the current assessment practices perspective. Moreover, issues with and challenges of the current assessment practices and their suitability for measuring the sustainability competencies and EGs were identified along with the potential improvements that can be done on this framework. Data and information gathered for the purpose of analyzing the QES were obtained from the Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MoEHE) statistical reports and exam results [14,15,16]. National strategy documents from different sectors (QNV 2030, education strategy and ETS) were used to understand general policies and rules of education in general and assessment procedures in particular [11,13]. To further understand these policies as they are related to the procedures of student assessment, interviews were conducted with teachers and MOEHE staff in the assessment field [17,18].

2.1. Theoretical Analysis Methods for Comparisons and Benchmarking

This part of the research is aimed to introduce the best-practices of performance assessment strategies among high-performing countries by means of benchmarking. The methodology to accomplish the comparison between countries is known as the Method of Agreement (MoA) [19], or the Most Different Systems Design (MDSD) [20], which compares different systems that have the same outcomes. This method relies on exposing the independent variables to find the outcomes and similarities between countries as a critical factor towards academic excellence. For this part of the study, we focus on the educational goals that each system is trying to achieve and the variety of assessment approaches that are used to achieve these goals and SDGs. The assessment strategies of top-performing Western and East Asian countries are compared based on progress towards the achievement of 21st century competencies. Different education policies and philosophies will be examined, focusing on identifying the factors behind the best performance in academic achievement. The main objective of this comparison is to learn from successful experiences of countries that have similarities with Qatar in many aspects such as economy and demography. This allows the comparison to be more helpful for developing a proposed framework and student assessment system in the QES to achieve the intended goals and SDGs.

2.2. Qualitative Data

Following the comparisons and benchmarking, a PA framework will be developed and customized for the QES and its education policies in the context of its culture and society. This calls for conducting a set of interviews to fully understand the needs of the QES to complete the requirements for developing a PA framework. It is worth noting here that the contents of the quantitative survey will be constructed and designed based on these semi-structured interview results in a way that allows them to be used for further studies to improve and validate the proposed PA framework for the QES. The qualitative data can help to get a first impression of the current PA practices, understand the main factors behind the low performance on national and international assessments, and fully understand its challenges to identify the improvements that need to be made. The qualitative research at this stage of the project is essential for answering questions about the current PA system and the potential improvements from teachers’ perspectives towards such practices.

The interview process is a qualitative research approach used to obtain in-depth information on this topic. According to Robson [21], there are three types of interviews used in social research: structured, semi-structured, and unstructured. In this work, a semi-structured interview is used since it has many advantages including flexibility as it allows participants to explore the different aspects of questions as they arise during the interview [21]. Interviewees are asked to respond to the questions in writing on the schedule in addition to an informal discussion during the interviews. The semi-structured interviews with predetermined questions are conducted for teachers chosen at random from government preparatory schools. The first draft of the interview design was developed with fifteen (15) open-ended questions divided into four main aspects: (i) demographic information (social, education, and professional status), (ii) the QES overall, i.e., measuring awareness levels of EGs, SDGs and QNV, and identifying needs and challenges in the QES, (iii) the current PA system, i.e., identify the issues and barriers in terms of assessment practices and its strategy), and (iv) potential improvements for the PA (potential recommendations and improvements suggested by interviewees). Questions were open-ended so that the interviewees could use their own words to express their opinions regarding the different aspects mentioned above. Preliminary interview guidelines were discussed with two education experts for the purpose of validation and determining the appropriateness of language. Following their feedback, a variety of changes were made to the interview design and some questions were deleted or merged due to redundancy or similarity. As a result, the final interview consisted of nine open-ended questions.

2.2.1. Sample

The data were collected from four government preparatory schools, including two boys’ and two girls’ schools. The selection of schools was based on specific criteria including (i) the performance of schools on national and international exams, with one high-performance girls/boys school and one low-performance girls/boys school (ii) the number of Qatari students and teachers was equal to the number of non-Qatari students and teachers to avoid any bias and (iii) the location of schools near Doha city. This information is available in the School Report Card (SRC) from MoEHE. The participants of the study involve a total number of 20 teachers, 5 parents and 4 administrators from government schools.

2.2.2. Data Analysis Methods

Several guidelines are available for the analyzing qualitative data and there is no single accepted approach for this process [22]. Thematic analysis is a qualitative method that can be applied to a set of texts to identify common themes [23]. The interview transcript analysis for this work will proceed through different steps commonly used to interpret qualitative data but not necessarily taken in sequence. These steps of analyzing and interpreting qualitative data are performed first by reading through data several times to obtain a general sense of the material and to develop a deeper understanding of the information provided by the interviewees’ responses. A table of sources will be developed in Excel to help organize all the interview materials by date and participant. The second step is called coding, i.e., labeling relevant words, sentences, or sections that are frequently repeated in several places or that the interviewees explicitly state to be crucial [24]. Paragraphs or sentences related to one code are known as a text segment [25]. In the present research, the manual analysis of qualitative data is used to analyze text data by reading the data and marking parts of the text by hand using different color-codes to distinguish between the categories. The main reasons for conducting the analysis by hand instead of a computer analysis are the small database size and the ability to avoid the intrusion of a machine and have a hands-on feel [22]. Additionally, to avoid losing the meaning of the data as the interviews were conducted in Arabic language. The third step is to reduce codes by deciding which codes are important, and grouping similar codes to avoid redundancy, then creating categories/themes by aggregating similar codes to form a significant idea [26]. This step is more subjective than previous steps because data are conceptualized. After the categories were created and labeled, the most relevant categories and how they are connected was determined by identifying consistencies, differences, and relationships between them. The purpose of this step is to reduce the number of themes so that a report with detailed information about a few themes instead of general information about many themes could be written. In the last step, many options can be taken into consideration such as whether there is a hierarchy among the categories, whether one category is more important than another, and finally whether to draw a figure to summarize the result.

2.2.3. Limitations and Trustworthiness

The accessibility to data, documents or policies in the ministries is considered as a limitation. As this was a qualitative study, some of the common pitfalls can occur. For instance, when the participants may distort the truth or withhold, these can lead to inaccurate or biased data. This issue could occur if the participants do not see a benefit for them in the research. Hence, to avoid this issue, the participants were fully informed about the purpose of the study, procedures, and utilization of data gathered. In order to enhance the credibility of the study, it is very important to spend time on the field and engage with a multitude of participants. As more time is spent on the field, rapport with participants will increase and they will volunteer different and more sensitive information.

Another critical issue is ethics in the context of confidential information. This kind of ethical duty also applies on this information as its sources could be from organizations or other researchers or participants that have legal or other obligations to conserve confidentiality. Fulfilling the ethical duty of confidentiality is essential to the trust relationship between participant and researcher, and the credibility of the study. Hence, utmost attention is paid to ethical codes or laws that may require disclosure of information obtained in a research context.

In order to obtain the cooperation of the participants in this study, it is essential to inform them of the purpose of this study and utilization of data gathered [27]. The names of participants were treated confidentially to protect their identity. The participants were also informed that the information gathered from interviews will be used for academic purposes only while ensuring the confidentiality of their responses. Therefore, this study went through the process of approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) as well as the CITI certificate for Research Ethics and Compliance Training in order to ensure that the right steps are taken to protect human subjects.

Prolonged engagement and triangulation are two techniques used in this research to deal with trustworthiness. Using prolonged engagement strategy means spending sufficient time with interviewees in order to gain their trust and for better understanding of their values and behavior. Triangulation is used to increase the validity of research findings and reduce researcher bias by utilizing more than one method to collect the data. In this study, two methods are combined (qualitative and theoretical analysis) in order to increase confidence in the outcomes.

3. Theoretical Synthesis

This section compares the education systems and PA approaches of few select countries that are recognized as high performing in terms of the quality of their education for the purpose of benchmarking. It also provides a theoretical and comparative analysis of the QES to understand its current PA practices and issues.

3.1. Assessment Strategies in High-Performing Countries

This section delineates best-practices of PA strategies among high-performing countries by means of benchmarking. Assessment strategies of top-performing Western and East Asian countries are compared based on progress towards the achievement of 21st century competencies. The factors behind the best performance in academic achievement are also outlined. This section compares the education systems of three countries by finding similarities and differences in regard to the assessment strategies that assist in fostering high levels of student achievement. Qatar can benefit from such case studies to integrate ESD values within educational process and to enhance its k-12 assessment measures in order to address national strategies and vision as well as to attain academic excellence.

3.1.1. East Asian Countries: Singapore

Recently, results of international assessments such as the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), highlighted that Asian countries, including Hong Kong, China, Japan, Singapore, and South Korea, were top-ranking [28,29] in reading, mathematics, and science subjects. These results attracted the attention of Western countries and compelled them to consider emulating all aspects of the Asian model, from curriculum to pedagogy [30]. The reforms in East Asia aim to integrate 21st century competencies into their systems. However, the reforms extend beyond these competencies to emphasize the role of education in society by comprehensively reconceptualizing it. Although these countries differ in polity and ideology, there are many similarities in education philosophies and cultural heritages.

The five counties and their education systems mentioned above are considered among the most advanced economies due to their early awareness of the challenges of the 21st century [31]. These five countries have experienced comprehensive, significant and continuous reforms in their education systems to keep the systems in line with their economic development trajectories. This was accomplished by determining expected competencies and aligning them with their social values to define the features of a successful young person in the 21st century. According to Cheng [32], these societies have been relentlessly trying to continually improve and develop their education systems to meet the changing requirements for the 21st century skills. Since all the related reforms emphasize emotional and social learning by considering knowledge, skills, and attitudes to be only one dimension of the target goals, the five systems mentioned previously have mostly relied on experiential learning and active learning to achieve the intended goals [32]. Thus, the top 5 countries developed the methods used to assess students in a way that encourages them to acquire 21st century skills. This is accomplished by formatting assessments to be better suited for assessing high-order and complex thinking skills. For example, in Japan, the education reform shifted from testing “knowledge acquisition- what students know” to testing “knowledge application—what they can do with the knowledge.” In other words, Asian countries had changed the student assessment from testing their amount of acquired knowledge to testing their ability to use the knowledge [32].

In this study, Singapore is examined since it has become number one in achieving education quality outcomes compared to the wealthiest countries in North America, Europe and Asia. Moreover, although Singapore and Qatar have entirely different geographies, climates, cultures and developmental trajectories, they share similar characteristics such as small and open economies. Hence, Qatar could learn useful lessons from Singapore’s experience regarding its education system in general and its student assessment in particular. Singapore is a model that Qatar and other countries can emulate to develop, attract, and retain human capital and to seek their economies’ diversity into a sustainable growth model.

The education system in Singapore is centralized, meaning it is fully under government control. Singapore is considered one of the best learning governments that has the ability of high self-renewal. Thus, reforming their education system is a continuous process. Compulsory schooling in Singapore starts with a primary stage for seven-year-olds but, for those six years old or younger, pre-schooling is not mandatory. Primary students until their fourth year take the core subjects including Mathematics, English, Mother Tongue (i.e., Malay, Hindu, and Chinese) and Science, along with some of Physical Education, Health Education, Arts and Crafts, Music, Civics and Moral Education classes. In their fifth year of this stage, students take classes based on a scheme called “subject-based banding”. Students spend four years at the secondary stage, which is divided into four tracks, where each student enters one of these tracks based on their primary stage results. Schooling hours in Singaporean schools that follow the Ministry’s guidelines are five hours a day with a 20–40 min daily recess, but, as students advance in age, school hours get longer [33]. According to OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) reports [34], 15-year-old students in Singapore spend 9.4 h a week on homework.

With the beginning of the new millennium, Singapore’s Ministry of Education (MoE) developed an evaluation system known as the “Enhanced Performance Management System (EPMS)”. In addition to the system being used to evaluate observable elements such as instructional skills and classroom management, it also looks at unobservable competencies [35]. This system aims to serve the research and development of competencies by providing evidence of unobservable characteristics to identify and further develop the competency concepts. The second purpose of the EPMS is to serve teachers by identifying their strengths and weaknesses so that they can adjust their teaching style. Singapore MoE’s competencies have been classified into different clusters, where each cluster, consisting of similar competencies, achieves the intended education goal. Having a cluster system provides teachers with a framework for charting and tackling their progress and identifying their weaknesses and strengths. Overall, the EPMS is considered a tight coupling tool that would ideally provide learning development initiatives, ongoing research and monitoring by aligning with each other. The EPMS also offers succession, alignment, and sustainability through consistency within and between generations [36]. In Singaporean schools, one of the principal’s roles is to scrutinize teachers to ensure that they achieve the school educational goals. In the same context, the principal can use exam results to design the curriculum, manage teachers’ professional development, assist them with their problems, and observe their classroom practices [37].

Singapore’s experience indicates that improving the quality of education, creating an environment that encourages innovation, and attracting skilled labor are essential factors in creating more sustainable economic growth. In the context of students’ assessment, the records of Singapore students in Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMMS) [38] were ranked on the top and reached the advanced benchmark. These results are an outcome of developing the Singapore education system curriculum to adapt to 21st century skills and improving the assessment methods by emphasizing the understanding of the material and improving students’ skills instead of relying on memorization. This initiative is known as “Teach Less, Learn More,” and aims to eliminate observed shortcomings in social and critical thinking skills [29,30]. The development of the education system has focused on students’ acquisition of the right skills such as creativity, critical thinking, and life-long learning based on their interests and talents, by making massive changes to the role teachers play in student learning and learning activities [39]. Therefore, the standards for 21st century competencies define what the students should know and be able to do, which have developmental targets for each academic stage. These can provide a reference that allows teachers to be able to improve their plan for teaching and assessing 21st century competencies. The framework of these competencies, which enable students to acquire cognitive skills by teaching them how to apply creativity and critical thinking to real-life situations and synthesize knowledge from different learning areas, aims to prepare students for lifelong learning and challenges. Most of the reforms in Singapore have mainly been based on the science of learning which consist of three principles: (1) students become active learners by an emphasis on developing self-directed learning, one of the primary goals of the “Teach Less, Learn More” initiative; (2) experiential learning, which is attributed to interpersonal relations and a sense of responsibility that can only be acquired from experiential learning, thus, the formal curriculum in Singapore has been reduced to 33% to emphasize the importance of extracurricular activities and out-of-school experiences; and (3) allowing for diverse learning outcomes since students may achieve differently hence learning is enabled by using personalized learning pathways and opportunities. Thus, there is an emphasis on “project learning” which requires learners to creative problem solving and problem-based learning activities, plan their own activities and define their own objective. Singapore also uses “project learning” as a compulsory measurement of its tertiary education entrance examinations [32].

The philosophy of assessment in Singapore is built based on three tenets: “Assessment is integral to the learning process,” “Assessment begins with clarity of purpose” and “Assessment should gather information to inform practice.” Singapore has recently applied an initiative called “subject-based banding” where students in the fifth and sixth grades of the primary stage take classes in this scheme based on the scores they obtained in each subject (English, Mother Tongue, Mathematics and Science) at the end of the fourth grade. Then, at the end of the sixth grade, the students take another national exam known as the Primary School Leaving Examinations (PSLE). Based on PSLE scores, high-achieving students can select up to six secondary schools to apply to, while unqualified students are allocated to specific schools according to their location. When students exhibit that they are more talented in arts and sports than in academic studies, there are special secondary schools that support them [32]. At the end of the students’ fourth secondary year, they take another national exam called the General Certificate of Education (GCE). The GCE exam is divided into three levels (O, N(A), N(T)) based on the exam results of PSLE, where each level has a specific track: Cambridge, Normal (Academic), Normal (Technical), respectively. Based on students’ achievement on the exam results of GCE, graduates can enter post-secondary programs, but the highest-performing graduates have more options for self-selection into different programs. Singapore’s national exams (PSLE and GCE), also called Singapore Examinations and Assessment Board (SEAB), are aligned with the national curriculum’s objectives and are primarily used to properly allocate and place students for their next stage of education; they are used for benchmarking purposes, as well. The national exams emphasize thinking skills by asking more questions that make students classify, compare, predict, analyze, interpret, evaluate, utilize judgment, draw conclusions, distinguish between facts, solve problems and make decisions. A variety of question formats are used such as structured, open-ended, source-based, coursework, oral and listening [40]. In Singapore, recent reform intended to reduce unnecessary examination pressure by creating a track that eliminates the need to take high-stake exams. This was done by creating exam-free tracks for entering high school and university. Singapore may also change the use of “one-off paper-and-pencil tests” to “student learning profiles” [32].

3.1.2. Western Countries: Finland

The Nordic countries, including Sweden, Finland and Norway, are similar in their cultures, history and linguistics. They also have a robust amount of cooperation in different areas. One example of this is having a common labor market. Nordic countries provide a decent life by pledging individuals’ rights and ensuring equal opportunities for social promotion, which are usually achieved by quality education [41]. The education systems in these countries have strong commonalities. Nordic countries’ education systems are distinguished by their high-quality education that is based on providing equitable and ensuring well-being and happiness for their students [42].

For our study, the selected country from the Scandinavian welfare state is Finland. One of the reasons for this choice is the significant similarity between Finland and Singapore, given that both countries endured from similar circumstances in their developing years of the 1960s and 1970s. Secondly, the two countries have highly ranked scores on OECD PISA examinations, including problem-solving, mathematics, and language proficiency. Both Singapore and Finland also have incredibly high scores in student resilience a category defined by students’ test results being measured across their expected performance according to socio-economic status [38]. Finally, although Singapore and Finland are both countries that produce favorable education results, their educational systems are vastly different, indicating that students can be educated in a variety of ways and still achieve high-performance levels [33]. Hence, this section focuses on examining differences in education systems between both countries regarding education policies and philosophies, even with the similarities hidden within all the diversity. This would be useful not just for the level of the QES but also for global education systems.

The education in Finland begins at the age of six at pre-school, where education is informal and not mandatory, similar to Singapore. Instead, this stage is used to focus on developing students’ social skills and their interaction skills with other students [43]. In Finland, mandatory basic schooling, which includes the primary and secondary stages, is called a comprehensive school, where the students start at the age of 7 and stay until 16. Finland’s educational strategy places all students with different ability levels in the same class, unlike Singapore, and does not distinguish between them. Instead, students with special needs are provided with support teachers [44].

In contrast to Singapore’s assessment strategy, Finland’s evaluation system is based on teacher-made tests and verbal assessments and does not include any standardized testing. From the first year through the sixth year, all subjects are taught by one homeroom teacher while, for the remaining years, specialized subject teachers teach related subjects. In the tenth year, students have three options and can choose the ones most appropriate for them. The first option is leaving school altogether. The other two options are that students can either go to a vocational school which, depending on their exam results, can lead to entering a university, or go to an upper secondary school where the only standardized test known as the National Matriculation Exam (NME), can be taken. When taking the standardized exam, students choose to be tested on three of the following subjects in their mother tongue: a foreign language, mathematics, the second national language and general studies (includes natural sciences and humanities). Both Finland and Singapore each have the same number of schooling hours a day but differ in the total minutes of recess, whereby students in Finland spend five hours in school with a 75-min daily recess [45].

Between the two countries, there is a large disparity in the amount of homework given. In Finland, 15-year-old students spend 2.8 h a week on their homework, while Singaporean students spend more than twice the amount [34]. This means that not only can the quantity of homework be a success factor, but the quality can also matter in the bigger picture. Thus, the amount of extra work that could be put in by students with the quantity of homework should be taken as well into consideration.

Unlike Singapore, the Finnish education system does not have a formal evaluation system designed to assess its teachers [33]. Nonetheless, assuring teachers’ quality by providing evaluations, feedback, occupation, and career advice is the responsibility of local leaders. This approach is described as dexterous because of its many features [46]. A characteristic of these features is that local authorities are familiar with the needs of students. Since the Finnish system’s philosophy is based on teachers’ trust, more appraisal efforts are spent on the teacher training system. This gives the local authorities an efficient role in developing their teachers by means of empowering the position of a teacher to effectively perform their job with minimum supervision [33].

Since the Finnish system is based on trust and autonomy, it also helps teachers have more authority in the classroom so they can deal with problematic situations independently. Giving Finnish teachers this autonomy allows them to be creative with their job, adjust the curriculum to fit their class, and empowers them in their work. Thus, the Finnish education system benefits from evaluation for the purpose of development, not control. This approach is advantageous because it creates a healthy collaborative teaching environment rather than a peer competition environment and allows people involved in the educational profession to share their best practices and findings [47]. However, according to Wilfred [33], when examining this Finnish approach mentioned above from the perspective of their teachers, it is seen that receiving feedback to improve student learning is not as beneficial as the use of student assessments. Although both Singapore and Finland are entirely different in their approaches to autonomy, both countries have shown success, which means that being successful at reaching academic excellence is not limited to a specific method.

Finnish schools’ educational goals focus more on developing a diversified student potential by providing hands-on classes from an early age, such as art and home economics. This is most likely due to their belief that learning exceeds the normal and traditional academic scientific themes; it is also about learning the meaning of life and community skills, developing a good self-image and sensitivity to others’ feelings, and understanding the responsibility of taking care of others. Moreover, the education system in Finland encourages students to practice self-learning to ensure lifelong learning and enhance the motivation of learning after receiving a degree. It can be indicated that social and interactive skills seem essential for a successful education system [33].

Due to Finnish students’ high performance and results achieved on the PISA, Finland has received global attention. The Finnish educational practices have been used as a benchmark since academics and policymakers assume that high-stakes exams, such as the PISA, are the best indicators of school performance and conditions [48]. The more interesting finding is that Finland has the lowest variance across schools, meaning that Finland’s test scores are equally distributed with no achievement gap among its schools and students [49]. This shows that the Finnish education system is based on providing equal opportunity in learning environment where all students with different capabilities are placed in same classroom. Since exam results are equally distributed, it is indicated that the Finnish approach supports individual differences and enhances human development by focusing on developing the weaker students [33]. Some studies correlate Finnish students’ high performance on the PISA to the lack of high-stakes standardized testing [50].

While most countries, including Qatar, have been aiming to raise their rankings on international assessments by having students take more high-stakes exams, the Finnish education system justifies its reforms using only the PISA. The assessment system in Finland is based on three types that take place in different periods: during the classroom activities, the final comprehensive exams, and the matriculation examination for tertiary education admission. While the National Core Curriculum for Basic Education 2004 guides student evaluation and aligns assessments with national criteria, assessing student behavior and tasks is the duty of teachers. Assessment in the Finnish education system primarily aims to improve the learning of students and instructors. Therefore, formative assessment is used in early comprehensive schools to assist students who need exceptional education support or have learning difficulties [50]. Classroom formative assessment is also used to measure behavior, educational progress and work skills to ensure that students are meeting desired objectives. Using formative assessment encourages students to self-evaluate performance, helping them become more aware of their progress and thinking and directing them to set personal goals. The Finnish National Board of Education encourages students to learn how to self-assess, a skill that also requires teacher guidance because it is a critical skill that enhances a learner’s ability to better understand their own strengths and weaknesses for their future work. Through the results of classroom assessments, students receive feedback from teachers regarding their learning progress and suggestions for improvement. Student progress reports are frequently shared with both parents and students, so they are both aware of the student’s strengths and areas that need improvement. The second assessment of the National Core Curriculum is the final comprehensive exams of basic education and it is carried out by subject teachers. The final assessment for each subject must be aligned with national criteria. Although test scores are used to ensure that students have met the desired objectives of courses, it is not acceptable to use them as the only assessment criteria. The last assessment, the matriculation examination, is the only high-stakes standardized exam. It is not included in the National Core Curriculum because Finland’s assessment strategy avoids formal and high-stakes assessments to reduce pressure on teachers who otherwise would have to prepare their students for assessments [49].

Finland is an excellent example of an almost exam-free education system and philosophy, whereas Singapore heavily emphasizes its assessments by using different modes of examinations at different stages of education. While both countries perform relatively high on international assessments such as the PISA and TIMMS (Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study), the differences in their educational approaches primarily stems from their differences in culture, social values, demographic structures and economic developmental histories. Finland has a relatively homogenous society with similar cultural, ethnic and geographical backgrounds, whereas Singapore has a heterogeneous society composed of local Malays, immigrant Chinese, and Indian communities of merchants and businessmen. Finland is also known as an equalitarian society, whereas differences in society are accepted norms in Singapore; hence, the Finnish education system, following its social norms, emphasizes equity and equality in resource allocation and achievements.

3.2. Theoretical Analysis of Current PA in the QES

The purpose of this section is to analyze and reveal the current issues and challenges of PA practices in the QES in comparison to SDGs and EGs. This theoretical analysis was used to modify the preliminary assessment framework by increasing focus on the assessments’ practice alignment with sustainable competencies. The main findings of this analysis are highlighted in this section and more details are available in the paper that is under revision for publication [5].

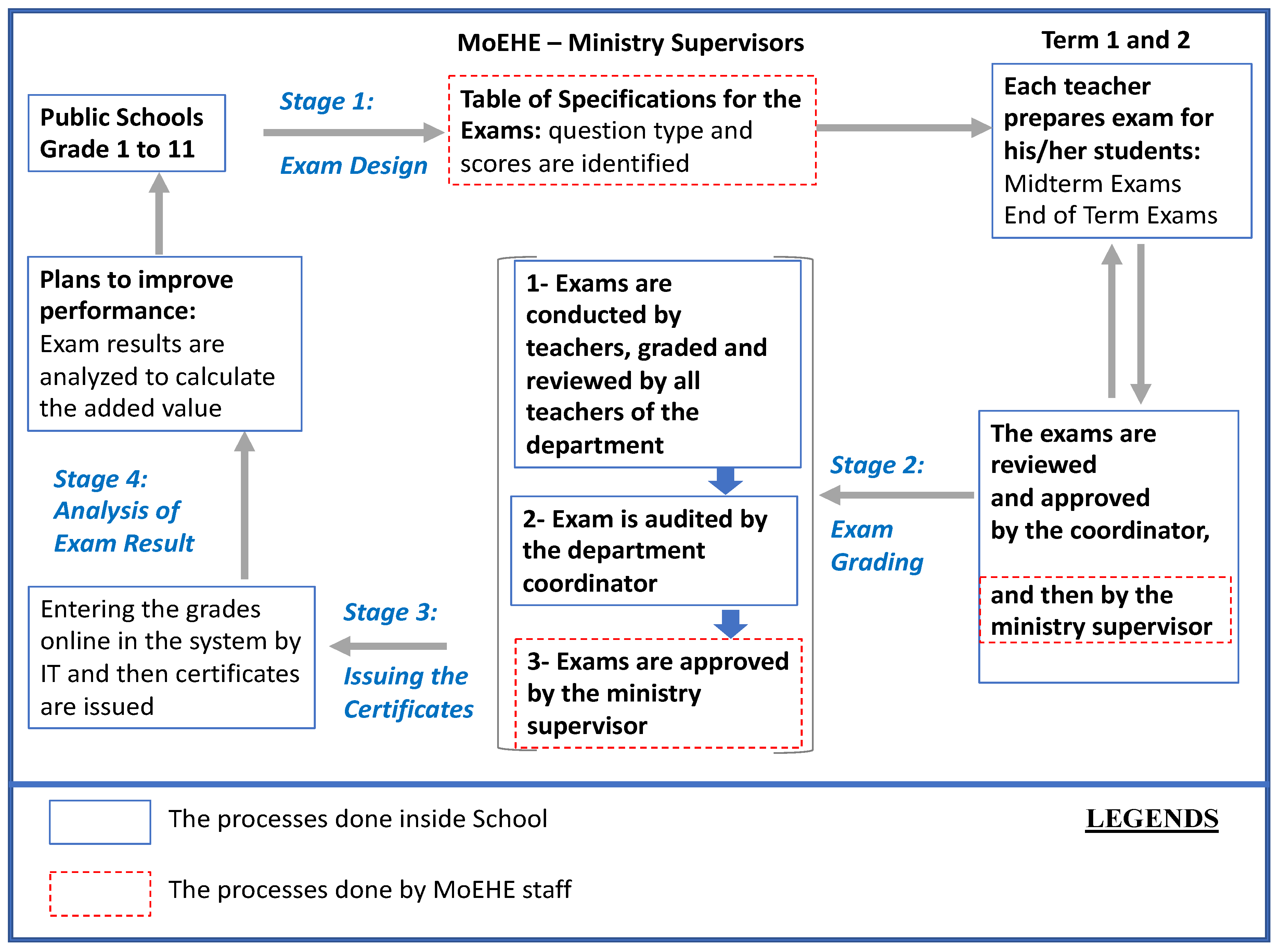

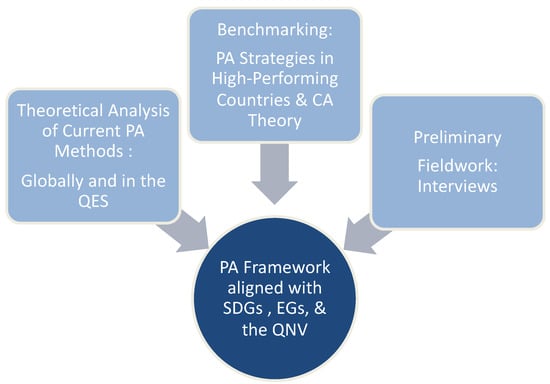

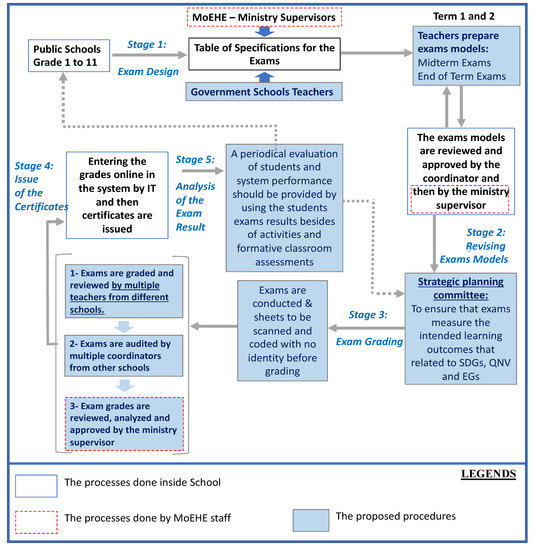

Improving the current PA approach requires, firstly, to identify the needs and gaps in the current assessment system particularly in its relation to achieving SDGs, EGs transparency and alignment of learning goals. Currently, in government schools (a.k.a. independent schools), the assessment process is divided into many stages, as depicted in Figure 2. Assessments are conducted four times during the two academic terms in a year: mid-term and final exams for each term [51]. The first stage is the exam design, for which the teachers prepare the exam for their classes per the MoEHE guidelines called “Table of Specifications for the Exams (TOS)” [18]. Each subject and grade have a TOS for the exams that provides a listing of the subject content areas and includes a number of items, type of each question, and its score to ensure that the teacher covers all the subject curriculum areas. The TOS is provided by the MoEHE supervisors only without involving the coordinators or teachers. The exam sheets and questions prepared by teachers are reviewed and approved by a coordinator in each school, and then by the MoEHE supervisor. In the second stage, after an exam is conducted by the teacher in their class, students’ answer sheets are graded and then reviewed by committees that usually comprise department teachers from the same school including the students’ teacher and sometimes teachers from the outside school (each subject has one department includes one coordinator and some teachers). For each answer sheet, the student’s name is covered, and each answer is graded by a different teacher, and then the same answer is reviewed by another teacher. The department coordinator then randomly selects some answer sheets and reviews them again to audit the grading procedure. After grading all the answer sheets, the MoEHE supervisor reviews and approves the grades by signing the exam/answer sheet envelopes. The third stage is entering the grades online into the system by the MoEHE IT at the end of term, and by the teacher at the middle of term. The last stage is sending students exam results for their teachers to analyze and calculate the “added values”. The teacher should, then, make a plan to improve their students’ performance based on the “added value” by calculating the number of students passing the exam, for which the scores are classified into three categories (low, medium, high).

Figure 2.

Students’ Performance Assessment Process for the academic year 2020–2021.

Many gaps that were revealed at different stages of the current PA process in the above description and some of these gaps were confirmed by the practitioners [17,18]. Teachers are not involved in setting up the table of specifications for the exam; this step requires input from the practitioners who teach the subject curriculum. However, this table of specifications is built based on the curriculum content but not the EGs, while the purpose of using it is measuring the thinking skills beside the knowledge of the subject. Furthermore, the table of specifications should be used to ensure that the exam measures the intended learning outcomes. Another problem emerges since usually the teaching materials including the books put together by the ministry for each level are not suitable for more than half of the class [17]. Procedures for exam grading, such as covering the student’s name and grading each exam sheet by a committee consisting of department teachers are supposed to make the evaluation more transparent and less biased. However, even when teachers get the exam sheets with covered names of students, teachers who are grading the same classes they teach can easily identify who are the students by looking at their handwriting [17,18]. In the last stage of the assessment process, the system provides teachers with the exam results to calculate the added value and the number of students passing the finals becomes higher. It is about quantity and not about quality and it does not reflect these students’ actual level, whereas it is better to spot the exact issue with the students’ level and work on fixing it.

The QES urgently needs to find ways to improve its education quality since several academic studies, government reports, and strategies have highlighted some of the core challenges in the system [11,13]. One of these challenges is presented by the education Global Positioning System (GPS). The GPS shows that the international assessment results for Qatar student performance are below the average when compared to other countries. Al-Khater et al. [52] emphasized this point by indicating that student performance on national assessments was deficient over the years as most of them did not reach 18% of the subjects’ requirements in most subjects. She mentioned that national and international assessments are the primary tool that can be used to measure any school’s performance and the overall education system [52]. This issue leads to basic education students not meeting higher education requirements since the students are not well prepared for post-secondary study. The vast growth of Qatar population with the number of expatriates, and the increasing demand for education could be one of many reasons for questionable education quality, as the demographic influx of a country plays an important role in sustaining the educational outcomes.

The national exam prepared by schools for grades 1–11 and prepared by the MoEHE for grade 12 relies on a summative exam format that focuses on memorization rather than skills such as analysis and critical thinking. This was exposed by MoEHE reports when it was mentioned that 90% of two terms’ final total scores were calculated from these exam results and only 10% was calculated from class activities such as projects and quizzes. As a result, most students are not taking the classroom activities seriously because the time and effort needed for these activities are not accurately reflected by the percentage of their overall score (10%). According to Brewer et al. [53], only relying on summative exams as the main method used for measuring student performance is not sufficient for measuring 21st century skills. Moreover, this kind of assessment leads to students struggling to improve themselves during the academic year since exams are taken at the end of each term, contrary to the formative assessment method.

Recently, some studies revealed that some Qatari students suffer from low motivation, which leads to them to passing terms without making actual academic progress, and eventually losing their interest in learning. Based on the QES analysis findings, the reason behind this issue is the lack of variety with both assessment practices and teaching activities which do not support the students’ interests. Another issue is that the QES components, such as teaching activities and assessment methods, are misaligned with each other and with both EGs and SDGs. Another challenge that the QES faces is having fewer qualified teachers. Around 95% of the teachers in public schools from Arab countries with varying degrees of academic backgrounds and professional and social aspirations [15]. Many of those teachers got their degrees from not well known institutions, unlike Qatari teachers, who mostly received their Qualified Teacher Status (QTS) from the College of Education at Qatar University, a regionally accredited institution of higher education. Therefore, to apply appropriate pedagogical practices, qualified teachers with QTS are needed to ensure having a better and improved educational system. According to Biggs and Tang [54], teachers’ capabilities are reflected in both the pedagogic approaches and assessment techniques and their abilities to use the constructive alignment theory for system components.

4. Qualitative Data Analysis: Interviews

In this section, results and findings from a qualitative analysis based on interviews are presented and discussed to ensure a full and first-hand understanding of the QES’s challenges and identify the local improvement needs. This section also represents the discussions of the results from various comparative aspects from a local and global perspective.

4.1. Demographics

The sample considered for this research consists of different participants including 20 teachers, 5 parents and 4 administrators from government preparatory schools. The sample of this study is distributed homogenously as half of the sample was from two girls’ schools and the other half from two boys’ schools. Half of the teachers’ nationality was Qatari, and the rest were Arab (non-Qatari), which added a valuable comparative perspective. Therefore, during the interview, teachers were interviewed separately based on their nationality: Qatari, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC), Arab (non-GCC) since teachers from the GCC or other Arab countries may face different issues to the teachers from Qatar. More than 70% of teachers had 10 years or more of experience teaching in public schools. While almost half of the interviewees had a certificate from a College of Education from different institutions, only one case had QTS. The rest did not have a professional degree in teaching. The interviews were conducted with all teachers of all subjects (Arabic, English, Islamic studies, Mathematics, Science, Social Studies) as they may have specific concerns related to subject they teach. Of the sample, 25% of the teachers held a Master’s or PhD degree, while the rest of the interviewees had Bachelor’s degree. The results of the qualitative data analysis will be reported under the following categories.

4.2. The QES Overall

This part of the study aims to measure the overall satisfaction level of the QES and the awareness level about EGs, SDGs or sustainability, and the QNV 2030. More importantly, it emphasizes on identifying the overall needs, challenges and constraints in the QES.

- Awareness of EGs, SDGs and the QNV:

The teachers were asked to indicate whether they were aware of EGs and SDGs and were asked to comment on the current situation of the QES and the relationship between education in Qatar, SDGs, and the QNV. Teachers’ answers revealed that the education goals are clear, including critical and analytical thinking and communication skills, but they mentioned that the traditional pedagogy and curriculum are not motivating the students. Most interviewees noted that the SDGs are not clear and that the learning/teaching activities are not explicitly related to sustainability. One teacher added “some projects and activities may relate to sustainability but need to be with clear and explicit goals”.

- Challenges:

Teachers were asked to explain their views about the current level of Qatar’s Education System and student achievements in terms of investments and reforms Qatar has made so far in education. Moreover, they were asked to determine their views about the role of each factor in education, such as schools, teachers, parents and PA, focusing on the overall quality of education. Additionally, teachers were asked to identify overall issues and/or barriers in the education system.

The majority of teachers emphasized that all factors in education together play an essential role in the education system, but some believed that the teacher’s role is the most significant and effective in the system because teachers are the core of the system. For the most part, teachers reported similar opinions about issues and barriers that teachers in the QES face. Common issues stated are low intrinsic motivation and ambition among students and weakness in supporting parents in helping with their kids’ learning process, where parents expect them to only pass to the next grade. Some teachers added “there are many students who do not have ambitious”, and that “the parents have a powerful role in educational process and in motivation their kids.“ In addition to these obstacles, grade 7 teachers faced a problem with students transferring from the primary stage, as a critical transformation stage from primary to preparatory, where they noted that the outputs of the primary stage are not eligible for the next stage due to being weak in literacy. Some teachers additionally reported that there is a lack of qualified teachers in all the educational stages. Finally, the heavy homework load and long school hours were identified as barriers to achieving better outcomes.

4.3. Current PA Practices in the QES

This aspect aims to identify issues and barriers in terms of assessment practices and strategy. It also measures the participants’ overall knowledge of the PA system and its effectiveness role in improving the outcomes parallel with teaching practices.

- Challenges:

Teachers were asked to discuss the significant concerns about performance assessment practices and their opinions about the correcting and grading/reporting process of student PAs. They were also asked to identify the issues and/or barriers that prevent students from achieving their full potentials. Almost all the teachers reported that the score distribution is unfair since the total score assigned to classroom activities and research is extremely low (5%). According to teachers’ discussion, this problem leads to an unreasonable teacher responsibility load since these types of activities take a large amount of effort to grade, an effort that is not reflected in the students’ final grades since these activities make up such a small percentage. One of the teachers pointed out that, “Most students assign someone else to do their research or projects, such as private tutors or writing services. They are avoiding any efforts in doing such activities because they account for such a low percentage of their final scores and they can succeed without doing them.” Some teachers stated that the assessment methods primarily focus on the quantity of knowledge rather than the quality of skills. Teachers argued that they are not involved in the assessment process and do not have the power to distribute such grades because they only receive the timelines and exam criteria, such as the form of exam questions and the grades for each type of question, from the MOEHE. Moreover, the teachers reported another problem with the MOEHE, a low number of supervision regarding assessment practices processes such as the writing and evaluation of exams, since some teachers leak the exam questions to their students. Finally, the lack of consideration of individual differences and focus being placed on raising school performance for the sake of the school’s reputation rather than improving the outcomes and skills of its students were identified as obstacles preventing students from achieving acceptable academic performance.

- Potential improvements:

Teachers were asked to make suggestions and discuss their perspective of the improvements needs for the current PA system based on their observations and experiences (How to assess methods and contents and in what dimensions/directions student achievements levels can be improved). Teachers provided many suggestions for assessment strategy for the QES. Some teachers suggested developing examination formats because most questions in the current exam format were based on rote memorization as mentioned above, so they suggested that the types of questions focus on critical thinking and skills acquisitions more. A recurring suggestion was to “involve the teachers in setting up the assessment criteria and the whole process of student evaluation itself”. Other teachers identified a need for aligning the assessment criteria with EGs and skills.

4.4. Summary of Findings

The qualitative data analysis reveals that an education system cannot be separated from its elements because it is an integrated complex system, where some parts impact others. Teachers from different public schools and nationalities share similar concerns about the QES overall and current assessment practices.

All of the interviewees pointed out that the existing assessment practices have many issues such as narrow scope, focusing on a single dimension of education goals (i.e., knowledge gains), disregarding or discounting other dimensions (such as skills, values, purpose), lacking the right tools and misaligning with teaching and learning activities, EGs, QNV and SDGs. Most teachers believed in the importance of having qualified teachers at all educational stages and parent support/involvement to improve student performance and their acquisition of cognitive skills. Regarding the performance assessment process, teachers identified similar issues and obstacles such as the distribution of scores being unfair and poor supervision of the assessment practices process. Therefore, most teachers mentioned that involving them in the strategy of PA is essential since they work in the fields of learning and teaching practices and are considered the core of the education process. These results will be used to develop the preliminary PA framework and fill the gaps missed in the QES from the perspective of assessment strategy and its relation to SDG/EGs.

4.5. Overview of Results

The previous analysis of Singapore, Finland, and Qatar’s education systems and assessment strategies have been investigated to distill schooling policy differences between them such as schooling hours, desired objectives, and educational philosophy. The comparison focuses on basic education from age 7 to 16 since skills are more easily and much more quickly acquired in early education. This is also the most critical educational stage since students are being prepared for future skilled labor and for the upcoming next stages.

The quality of any education system can be affected by a multitude of factors. This study primarily focused on factors related to education system policy issues in the three countries, and any non-education factors that contribute to immigration and economic performance were isolated. Most of the research has addressed specific education elements such as principals, administrators’ staff, and teachers, without integrating these elements or considering indirect factors, contrary to the research done in the present paper. Some literature has also criticized the use of assessment scores as a metric of student achievement since these scores focus more on the academic side than the assumed social and personal development successes of the education system.

Continuing to use exam results as a dominant indicator of school and system performance can negatively impact the future of education and it may lead to biased evaluation of student as well. Doing so can affect teachers’ primary role because their focus shifts away from student development and engagement to raising the student test results which leads to biased or unfair grading just to increase the score of students to pass the exams. This also leads to skew the education system far away from improving the outcomes of students. Because of this, we chose to avoid entirely relying on international or national assessment results as a main indicator used to measure the desired education goals and SDGs.

Singapore, Finland and Qatar’s education systems are different in many ways but are all similar in that their social, political and economic statuses are stable. This common denominator between the three countries provides a healthy and appropriate environment for schools to exist and students to develop. Furthermore, providing financial and social security in these countries allows students to focus on learning and creates more secure jobs for teachers and school staff. As mentioned earlier, Qatar and many other countries spend a large amount of money on educational policies, training and administration costs, an amount unfeasible without some level of economic stability.

The interesting point of conflict between Finland and Singapore, although both countries have been lauded, is vastly different education systems. This indicates that there are multiple ways to educate students and produce positive outcomes. The obvious conclusion to be made here is that the Singaporean system is exam-heavy and extremely strict while also being well-formulated and systematic. In contrast, the Finnish education system emphasizes equality in standards and lacks standardized testing [55]. The Finnish education system is based on trust and self-learning, while the Singaporean system is based on a guided approach that provides constant monitoring and tweaking.

Like many Asian countries, Singapore is considered to have a pressure-cooker education system, but this type of system is not the only way to produce good education results. In the context of Qatar, the QES has passed many reforms that rely upon national and international high-stakes testing in attempts to raise student achievement at the national and international levels. According to literature, this way of assessing student achievement may result in “teaching to the test”. Indeed, many Asian countries are also accused of following this approach, whereby teachers adjust classroom practices to prepare students for assessments [56]. Following this approach does not assist students in becoming well-adjusted citizens.

Even though Singapore, Finland and Qatar have different EGs, they all seek to produce confident, intelligent and well-minded students. Because Qatar has directed an immense amount of attention toward high stakes national and international assessments, further consideration should be given to educational policies, assessment practices and pedagogical approach. While Qatar aims to improve its students’ performances in international and national assessments, the Finnish education system has proven that there is no need for large-scale assessments.

This work compares three countries’ education systems by finding similarities and differences in what assessment strategies they use to assist in fostering high levels of student achievement. The results revealed that each country has a philosophical stance that reflects its policies and education system. Taking this into consideration, it would be better for Qatar not to copy and implement the policies of others such Singapore or Finland and expect the same outcomes since each country has a different culture and geographic influx. Besides, some studies suggest to beware imitating any country’s entire educational system as the nation’s politics and culture cannot be easily transferred [44,49]. While Finland, Singapore and Qatar are all small countries, Finland’s reforms work with an almost homogenous population. Such reforms would be difficult to implement in Qatar because the country has a large disparity in demographics and immigrants. Moreover, each phenomenon has different impacts depending on the society they are appeared in. Table 1 shows a comparison among the three countries in terms of demography, economy, energy and environment, and education system.

Table 1.

Examining different indicators at the demography, economics and education levels to get a more in-depth perspective of Qatar, Finland and Singapore.

Thus, presenting a model that details policy measures can lead to the proposal of a PA framework specific to each education system because it considers unique extraneous factors and challenges. Since the literature suggests that each country’s education system must be adapted according to the country’s circumstances and the overarching philosophy governing the country, the next section offers a customized and unique PA framework for the QES.

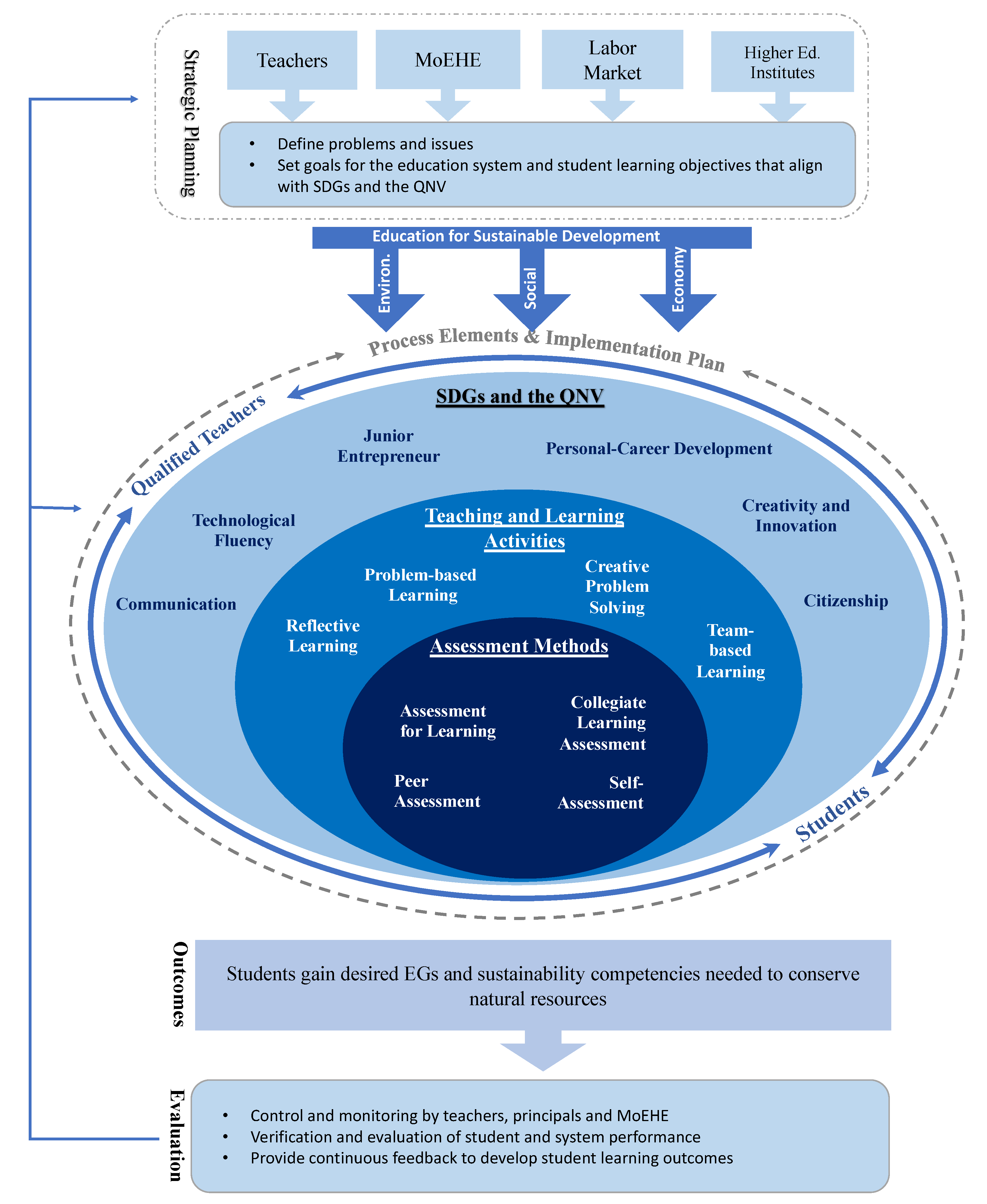

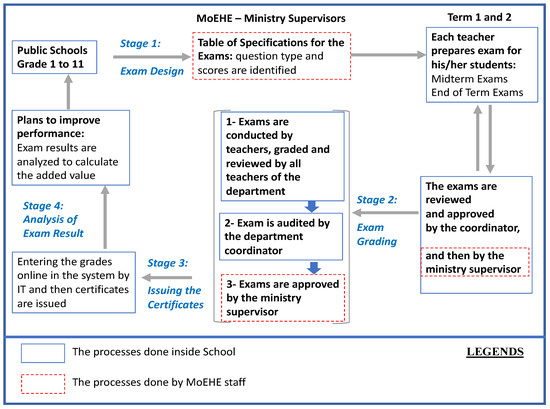

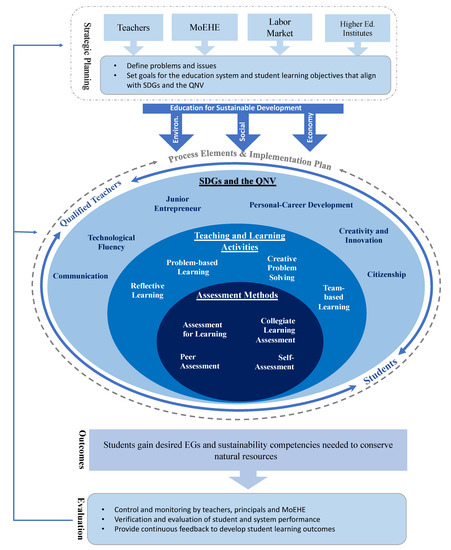

5. Modified PA Framework

This study has a significantly improved and detailed PA framework for QES based on the preliminary findings of a previous study by the co-authors [5]. This improvement is also based on using the constructive alignment theory to align all education elements that directly or indirectly affect the PA (Figure 3). The proposed PA framework aims to improve the learning process and assessment strategy and align them with SDGs and EGs. The development of the PA framework was based on a theoretical analysis of the QES, comparative analysis of high performing countries and qualitative data collected from public schools. This PA framework also aims to improve teaching and learning practice and assessment practices so that the education system can ensure that all students are qualified for life, college entrance, and workforce readiness for a competitive and innovation-driven economy and move to a more sustainable future. The locally developed PA framework provides recommendations for the assessment tasks and learning processes best practices specifically considering the social, cultural, economic, demographical and governance context of the QES in terms of SDGs and EGs.

Figure 3.

Structural framework—adapted from [5].

The design of the developed PA framework draws on a group of principles to improve the effectiveness of procedures related to performance assessment and its evaluation. These include relying on teachers’ capabilities, focusing on students and their outcomes throughout the educational process, building a more resilient educational system that accepts such changes to adopt and ensuring continuous improvement of student evaluation process. Transparency is also a must in monitoring and reporting of PA results to ensure that the framework and its core components are aligned for resilient development and scalability [57].

The ultimate objectives of the proposed PA framework are to enhance student outcomes and meet the desired skills and sustainability competencies. This can be achieved by improving teaching and learning practices and assessment strategy, and setting clear goals and intended learning outcomes that align with the QNV and SDGs.

5.1. The Components of the Framework

The main components of the PA framework (Figure 3) proposed in this study are presented with details as follows:

- Strategic Planning

Responsibility for the strategic planning of the PA framework should be shared among a wide range of stakeholders, including teachers and members of the MoEHE, labor market, and higher education institutes. This main role of the strategic planning committee is to identify issues related to assessment practices and students’ outcomes. From these findings, the committee should set SDG- and QNV-aligned goals for meeting intended learning outcomes.

- Goals and Intended Learning Outcomes (SDGs and the QNV)

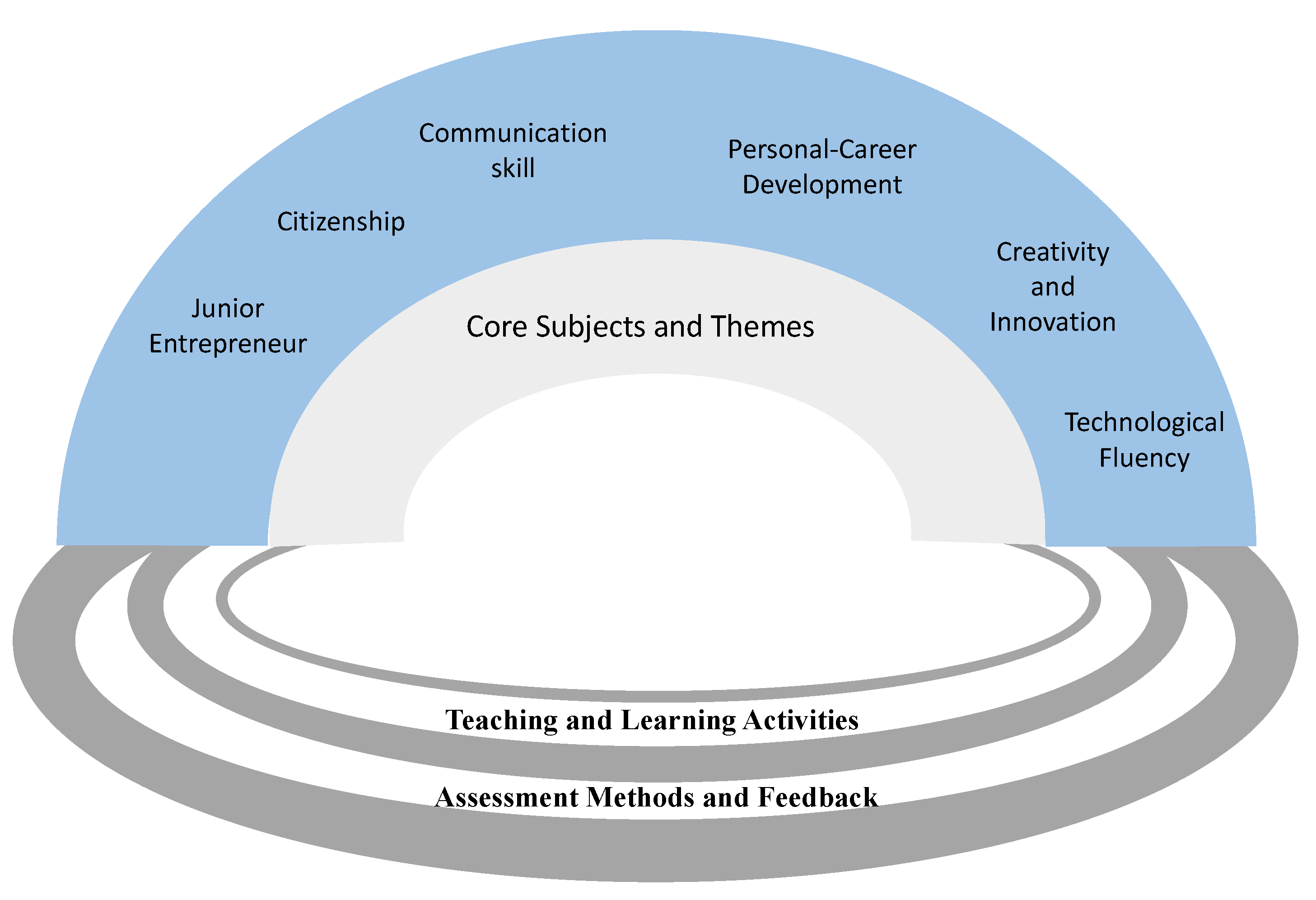

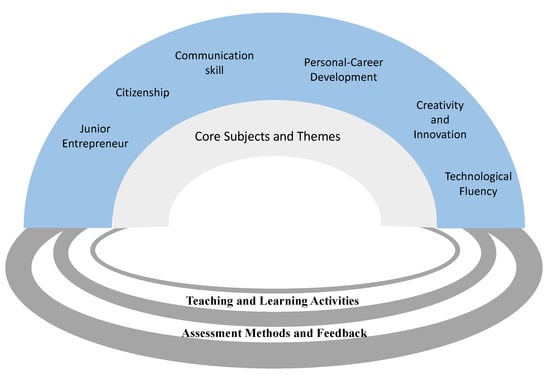

It is essential to align sustainability competencies with the intended learning outcomes by adapting the sustainability issues with teaching and learning activities. Further, the goals of both the QNV and SDGs should be merged with those of the intended learning outcomes and EGs. To do so, student knowledge and skills should be built on competencies that are related to 21st century skills and should align with the interdisciplinary themes (core subjects and themes) listed below (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The main education system components that have a direct impact on education goals (EGs).

Citizenship (also known as civil literacy): students should contribute to the sustainability of the environment, communities and society by analyzing environmental, economic, cultural and social issues; solving problems; making decisions and judging at a local and global level.

Personal career development: enables students to become self-aware and self-directed individuals by setting and pursuing goals aligned with sustainability and the QNV and making decisions regarding wellness and health, and career pathways. Moreover, social and cross-cultural skills are essential for students to interact effectively with others, enabling them to work with diverse teams. Two of the principles previously referred to in the text are accepting learning process changes and continuous improvement; these principles require flexibility and adaptability skills. Students must learn to be flexible to ideas that are not their own and adapt to change. Students should be able to demonstrate productivity and accountability when managing projects. Additionally, the students must be able to show responsibility to others, for example, to take responsibility for their role in teamwork.

Creativity and innovation skills: students show openness to new experiences and generate new and dynamic ideas by gathering information and collaborating to create and innovate. Students learn from errors, accept critical feedback and take responsible risks in this matter.

Communication skill: students can express their ideas about issues surrounding human rights and environmental sustainability effectively by participating and interacting purposefully and respectively in debates and conferences.

Junior entrepreneur: one of the essential goals of the QNV that emphasizes diversity in the economy as well as preventing the economic imbalance by enabling students to participate in the strong local and international market competitions, develop and apply creative abilities to communicate ideas and use critical thinking skills. Furthermore, entrepreneurship can develop the leadership and responsibility skills of the students.

Technological fluency: students interact with technology to collaborate, communicate, create new knowledge, innovate and share information. This becomes a very important factor to sustain the progress of learning nowadays where most of students have experienced a sudden move to virtual environments and virtual learning due to the pandemic.

- Teaching and Learning Activities

Choosing appropriate learning activities is essential to helping students achieve these learning outcomes and support sustainability competencies by adequately addressing SDGs and EGs in a timely manner.

- Assessment Methods and Feedback

Assessment methods and feedback aim to measure students’ abilities and how well they achieve their intended outcomes and develop students’ learning process by providing continuous feedback. According to Clarke [10], effective assessment tools use a feedback loop to offer both quantitative and qualitative information to stakeholders so that they can improve student learning. Taking this into consideration, learning and teaching activities and assessment practices need to work together to support the quality of achieving the outcomes. In Qatari public schools, analysis of the QES exposed that assessment practices rely heavily on summative assessments. Thus, this framework focuses on using various class activities and formative assessments to assist students with improving in their areas of weaknesses and give teachers feedback on student progress. Moreover, Tan [58] indicated that formative assessment can be used to enhance student learning in the short term since it provides them with feedback that allows them to improve their work.

5.2. The Implementation Strategy of Framework