1. Introduction

Communication and agriculture find nexus in humanity globally. Nevertheless, indigenous language makes the difference between them. Society cannot but communicate just as man cannot but farm. However, without one, the other fails. That is the compelling reason for goal two of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations Organisation (UNO). The goal emphasises the existential need to end hunger through food security and agriculture [

1]. By 2030, it aims to end hunger and malnutrition and ensure that all people, particularly children and vulnerable individuals, have unfettered and informed access to adequate and nourishing food throughout the year. To achieve this goal, agricultural practices must be improved upon, backed by complementary and accustomed communication channels to reach out to farmers who are the major stakeholders in this sector. Unrestricted access to media, technology and information is needed to grow knowledge, which nurtures farming practices. However, there are doubts whether indigenous language, the right medium and agricultural activities are well mixed to achieve goal two of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG’s) in many parts of Nigeria, especially the north-central region of the country [

2,

3,

4].

Oyero [

5] believes that “combining the potentials of radio stations with the benefits of indigenous language will, to a great extent, bring to realisation the purpose of communicating development messages”. It can be argued, therefore, that at its most basic level, the utilisation of indigenous languages for farmers can guarantee adequate understanding of a stream of information on composts, pesticides, high yield seedlings, proper planting seasons, water supply and conservation, in addition to teaching farmers ways to market their products. Communicating information on these issues would be made less demanding by utilising indigenous languages in agricultural training and extension administration, which bring new agro-technologies to the farmers to expand their yields and profit, upgrading their ways of life. The way forward in achieving this is to encourage languages which farmers know and can easily relate with. References [

6,

7,

8] note that farmers draw information from diverse sources to enhance their expertise. Hence, if farmers are communicated to in their languages, it becomes less demanding for both the facilitator and the farmers themselves.

Nigeria is a multilingual country with over 500 languages and dialects [

9]. Nevertheless, only a small number of these languages are national, regional, or state. A more significant percentage of them are local languages spoken by a few people in minority groups. Only Yoruba, Hausa and Igbo are also in practical terms three regional indigenous languages. They seem to have only achieved regional status with Hausa in the north, Igbo in the south-east and Yoruba in the south-west. English still dominates communications at every level, and, while it is not unique, English can be the actual national language.

As a multilingual nation, the option of languages to be used at national, regional and state levels as “the people’s official language” has been a challenge in implementing language policy in Nigeria. Furthermore, national or regional speakers only belong to a group of individuals or ethnic groups and therefore have a national or regional relevance or none [

10,

11]. It explains why English has taken precedence over the country’s various native languages because it is easier for people to talk openly in English than in their native language. English as a contact medium in formal and informal settings is preferred than the hundreds of Nigerian indigenous languages. For most developing countries, [

12,

13] partially attributes to the colonial past of the population the superiority of foreign languages over the indigenous languages. He notes that relations in indigenous languages were adversely influenced by the fact that they were colonised.

Communicating in indigenous languages has been noted to improve social attachment, encouraging African societies’ conservation [

14,

15]. Refs. [

16,

17] note that language plays a vital role in all areas of human endeavour because it is a conduit through which human beings communicate. Such communication ranges from face-to-face situations to mass mediation tactics. Hence, using indigenous languages to connect with agricultural communities through the media, especially radio, gives the listener a sense of belonging. Studies have demonstrated that indigenous language in radio broadcast is the best conveyor of mass communication since it achieves more with little efforts as against other media of mass communication, and is comprehended by the group of listeners [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22].

Just as the world battles hunger to sustain humanity, so do farmers battle the land for good yields. Without the success of the farmer, the world would lose its battle. Therefore, when the farmer speaks, the world should listen. However, to say, farmers, especially in agricultural settlements in Nigeria, do not have access to all the world’s media. For example, minute power supply renders television ownership and viewership unattractive in the country’s north-central region. Newspapers, mostly published in the English language, become outdated on arrival at the farms, serving as food wrappers. Social media is distant from the farmers, few of who own digital devices with data compatibility or internet access. Radio is affordable, battery-powered, sometimes rechargeable, mobile, and compact. Radio is the farmers’ companion that works without distracting its owner at work. It educates, entertains and enlightens while the farmer sprays the crops at the same time. Radio ownership and listenership are indigenous, at least in agricultural settlements in Nigeria. Nevertheless, there are concerns about whether the languages of radio programmes could be indigenous to support agricultural communication, most notably in influencing productivity [

23,

24].

Knowledge, acceptance and behavioural change towards agricultural radio programmes entails farmers’ comprehension of these programmes and agreeing either expressly or by conduct to align with the programmes and also making efforts to adopt the innovations outlined in the programmes on their farms. Thus, they change their initial attitude towards farming by imbibing lessons learnt from the programmes aired on radio in a language they can easily relate with. Actions and opinions in this context refer to farmers’ knowledge, attitude and acceptance of agricultural radio programmes aired in indigenous languages and their willingness to imbibe lessons learnt from the programmes to improve their agricultural yield.

Thus, this study investigates the influence of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages on farmers’ productivity and its implication for improved farming practices in North-Central Nigeria. The study is guided by three hypotheses: Farmers’ knowledge of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages has significant influence on their productivity; farmers’ acceptance rate of agricultural radio programmes has significant influence on their agricultural yield; behavioural change as a result of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages has significant influence on farmers’ productivity. These hypotheses are presented in the alternate format.

2. Materials and Methods

The use of a survey research method for this study becomes necessary not only because the technique “allows the collection of information from a representative sample of a target population but because it could also capture group dynamics amongst the various categories of the respondents” [

25]. Plateau, Nasarawa and Benue State were selected as the area for this study; the states are located in Nigeria’s north-central geopolitical zone. It has an approximate population of 1,150,000 farmers as indicated by the All Farmers Association. The geopolitical zone under focus is acknowledged as the highest contributor to Nigeria’s foreign exchange earnings in agricultural crop export [

26,

27,

28]. Additionally, the states emphasise radio programmes related to agriculture broadcast in indigenous languages against other states in the geopolitical zone [

29].

A sample of 663 respondents from each of the selected states was chosen randomly for the study. The sample size was ascertained using the Krejcie and Morgan [

30] sample size determination table. Each of the three selected states was further delineated into three agricultural zones. The three zones are zone A, B and C. Each is a senatorial district. Benue State has three zones, made up of Benue North-East, Benue North-West and Benue South. For Nasarawa State, they include Nasarawa West, Nasarawa South and Nasarawa North. Plateau has Plateau South, Plateau Central and Plateau North. The researchers selected two agricultural zones from each of the states under study using the lottery method of simple random sampling. The farming zones’ names were written on paper pieces and then appropriately folded, put in a container and thoroughly shaken before being picked. A volunteer picked out the first two zones for each state.

All the local government areas in each agricultural zone per state are similar in terms of geography. One local government area was randomly selected using the lottery method of simple random sampling as well. The local governments’ names were written on paper pieces and then appropriately folded, put in a container and thoroughly mixed before any picking. A volunteer picked two, which automatically made up the local governments from each zone for the study. Fourthly, the researchers stratified the local governments into two farming communities which amounted to four agriculture communities in each state. These farming communities from the two senatorial zones and local governments in the state were selected to give the researchers a desired study coverage. Hence, 55 farmers per district were selected from the local governments and farming zones through their Farmers’ Co-operative Society from the farming communities. The remaining three questionnaires were randomly distributed in one randomly selected farming community in each of the states, thus making 221 respondents per state as chosen for the study.

The questionnaire was designed to elicit general information about the study objectives from farmers in the selected states. Use of the questionnaire was based on the instrument’s effectiveness to obtain diverse opinions and feelings from the sampled respondents. The questionnaire was designed to measure respondents’ understanding, knowledge, perception and opinions. It consists of sections A, B, C and D, which tapped into information on the social and demographic boundaries to elicit the respondents’ perceptions, attitudes and opinions on the topic. Section A of the questionnaire contained fourteen items meant to generate information on farmers’ knowledge of agricultural radio programmes. Section B is made up of ten questions to generate data on farmers’ attitudes towards agricultural programmes in indigenous languages. Seven items make up section C to elicit information from farmers on their farming practices. Section D contains six items meant to generate data on the respondents’ demographics. In all, the questionnaire contained 34 closed-ended questions to avoid the problems of quantification and categorisation of the responses.

To measure knowledge, acceptance, behavioural change and productivity, the researchers developed the measurement instruments into 31 items representing the four domains mentioned above. Each of the domains were measured with a number of items on a 5-point Likert scale of strongly agree (5), agree (4), undecided (3), disagree (2) and strongly disagree (1). Based on the response options categorisation, the higher total scores on the scale indicate respondents’ opinion on knowledge, acceptance, behavioural change and productivity viz-a-viz agricultural radio programmes in the states under investigation. The questionnaire is provided as extended data.

For ethical consideration, eligible respondents were given a chance to comprehend the study’s goals and ask questions about the research and participants’ rights. Each respondent selected has the right to engage in this research voluntarily and the right to withdraw from the study at any point without any penalty whatsoever. Furthermore, respondents were not required to disclose their names or any other traceable identity to ensure that the information they gave cannot be traced to them. Thus, verbal consent was obtained from respondents.

The research route’s validity and reliability were established using the pre-test reliability method and Cronbach’s alpha. Cronbach’s alpha was used for all items’ overall value, and it resulted in a score of 0.969. The indicators for critical variables in the study, including knowledge, acceptance, behavioural change and productivity were higher than 0.70. The justification for using Cronbach’s alpha is that it is the generally accepted reliability test. Therefore, the thesis trajectory is considered satisfactory for the study. Data gathered were coded using Statistical Package for Social Sciences while hypotheses were tested using regression analysis and structural equation modelling.

3. Results

The focus of this section is on a statistical analysis of the formulated research hypotheses. The formulated hypotheses were tested through regression and structural equation modelling to determine the dependent variable’s significant influence. The hypothesis test helps determine whether there is adequate statistical proof or evidence in favour or against the proposed hypotheses. Most of the time, the hypotheses are stated in a null form. The goal is to either reject or accept a null hypothesis.

From the various age grades identified in this study and as seen in

Table 1 above, those within 18 and 50 had the highest distribution and fall within the economically viable range. This category of respondents forms the majority of the population of this study. Hence, it would be appropriate to infer that respondents for this study are viable for the kind of farming desired as a nation, i.e., the type of agriculture that will adopt innovations for improved Nigerian productivity and increase farm produce export to other countries across the globe. Providing information to these farmers in indigenous languages is a panacea to achieving this goal.

The gender distribution of respondents from all the three selected states, Benue, Nasarawa and Plateau, is presented in

Table 1. The gender distribution shows that more males are involved in farming in Benue and Nasarawa states than females. However, the situation is different in Plateau State, where the number of female respondents outnumbers males. This implies that both men and women are involved in farming in the three states under investigation. From the total number of respondents sampled, there is not much difference in males and females.

Moreover, there are more female respondents from Plateau than their male counterparts. This shows that women are not left out of the farming business but are willing to contribute their quota to the agricultural sector’s development. The states’ cultural differences may be another reason for the high number of women farmers in Plateau State compared to Nasarawa and Benue. Women in Plateau are more engaged in farming than their male counterparts.

Table 2 shows farmers’ knowledge of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages on farmers’ productivity. R in the model shows the strength of the relationship. The R value is 0.677. This suggests a significant relationship between farmers’ knowledge of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages and farmers’ productivity. The R

2 depicts the proportion of the farmers’ productivity variance that is predictable from farmers’ knowledge of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages. The R

2 value is 0.458, which if expressed in percentages, is 45.8%. This indicates that 45.8% of the farmers’ productivity variance can be explained by the variation in the farmers’ knowledge of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages.

Table 3 shows the influence of farmers’ acceptance rate of agricultural radio programmes on their agricultural yield. R in the model shows the strength of the relationship. The R value is 0.702. This implies a highly significant relationship between farmers’ acceptance rate of agricultural radio programmes and their agricultural yield. The R

2 depicts the variance in the agricultural return that is predictable from farmers’ acceptance rate of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages. The R

2 value is 0.493 which if expressed in percentage is 49.3%. This signifies that 49.3% of the agricultural yield variance can be explained by the variation in the farmers’ acceptance rate of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages.

The significant level for the p-value is below 0.05, which implies that the null hypothesis should be rejected. Still, if it is above 0.05, the null hypothesis will be accepted, following from the p-value of 0.000, which is less than the 0.05 threshold coupled with the fact that the F value is 558.358 at the 0.000 significant level. This suggests that farmers’ acceptance rate of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages significantly influences agricultural yield.

Similarly, the coefficient table shows the model that expresses how farmers’ acceptance rate of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages influences agricultural yield. The significance level below 0.05 implies a statistical confidence above 95%. This means that farmers’ acceptance rate of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages significantly influences agricultural yield. As above, the null hypothesis was rejected, and the alternative was accepted. Therefore, farmers’ acceptance rate of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages significantly influences agricultural yield.

Table 4 shows farmers’ behavioural changes due to agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages on farmers’ productivity. R in the model shows the strength of the relationship. The R value is 0.696. This suggests a significant relationship between farmers’ behavioural changes due to agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages and farmers’ productivity. The R

2 depicts the proportion of the farmers’ productivity variance that is predictable from farmers’ knowledge of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages. The R

2 value is 0.484 which if expressed in percentage is 48.4%. This indicates that 48.4% of the farmers’ productivity variance can be explained by the variation in the farmers’ behavioural changes as a result of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages.

The significant level for the p-value shows that it is below 0.05, which implies that the null hypothesis should be rejected. Still, if it is above 0.05, the null hypothesis will be accepted, following from the p-value of 0.000, which is less than the 0.05 threshold coupled with the fact that the F value is 558.358 at the 0.000 significant level. This suggests that farmers’ behavioural changes resulting from agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages greatly influence farmers’ productivity.

In the same vein,

Table 4 shows the model that expresses how farmers’ behavioural changes resulting from agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages influence farmers’ productivity. The significance level below 0.05 implies statistical confidence of above 95%. This means that farmers’ behavioural changes resulting from agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages have a significant influence on farmers’ productivity. As above, the null hypothesis was rejected and the alternative was accepted. Therefore, farmers’ behavioural changes resulting from agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages have a significant influence on farmers’ productivity.

Agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages have no significant influence on farmers’ productivity in North-Central Nigeria. This looks at all the measures of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages and how they affect farmers’ productivity using multiple regression. This allows us to see the contribution of each construct in the prediction of productive action.

Table 5 shows the influence of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages on farmers’ productivity. R in the model shows the strength of the relationship. The R value is 0.787. This suggests that there is a tremendous significant relationship between agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages and farmers’ productivity. The R

2 depicts the proportion of the variance in the farmers’ productivity that is predictable from agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages. The R

2 value is 0.619 which if expressed in percentage is 61.9%. This suggests that 61.9% of the farmers’ productivity variance can be explained by variations in indigenous language agricultural radio programmes.

The significant level for the p-value shows that it is below 0.05, which implies that the null hypothesis should be rejected. Still, if it is above 0.05, the null hypothesis will be accepted, following from the p-value of 0.000 which is less than the 0.05 threshold coupled with the fact that the F value is 558.358 at the 0.000 significant level. This suggests that agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages have a significant influence on farmers’ productivity.

In a related development, the coefficient table shows the model that expresses the extent to which respondents’ agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages influence farmers’ productivity. The significance level below 0.05 implies statistical confidence of above 95%. This means that agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages have a significant influence on farmers’ productivity.

To know the contribution of each measure of agricultural radio programmes, the beta value was used. It was discovered from the co-efficient table that behavioural change records the highest beta value of (beta = 0.320, p < 0.01, Sig. 0.000) followed by acceptance rate which recorded (beta = 0.300, p < 0.01, Sig. 0.000) followed by knowledge with (beta = 0.273, p < 0.01, Sig. 0.000). The findings imply that farmers’ behavioural change due to agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages has contributed significantly to the level of productivity of the farmers in the selected states. Further to the above, the null hypothesis was rejected and the alternative was accepted. Therefore, agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages have a significant influence on farmers’ productivity.

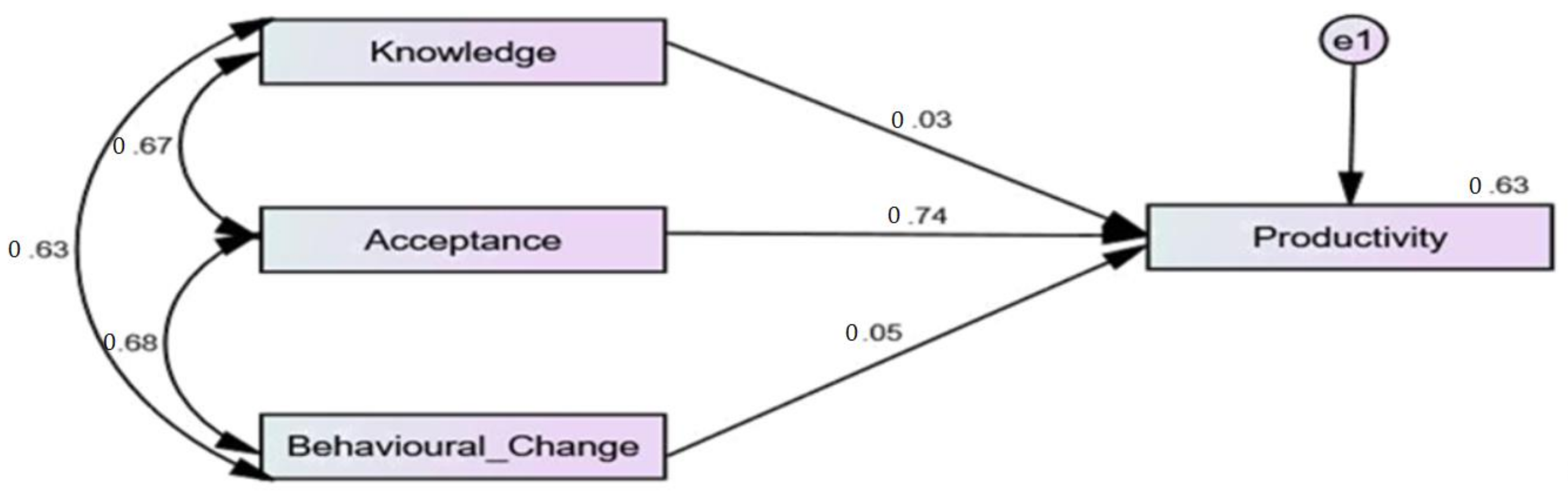

Figure 1 shows the output of the model of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages to predict farmers’ productivity. The model fit shows that NFI = 0.950, GFI = 0.873, CFI = 0.921, RFI = 0.921, RMSEA = 0.585 and Chi-Square = 227.786. The result shows that the minimum benchmarks were attained. Standardised estimates of the structural model of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages in predicting farmers’ productivity are depicted in

Figure 1 and

Table 6.

Table 6 shows the covariance between agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages (Knowledge, Acceptance and Behavioural Change) and farmers’ productivity. It was discovered that agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages co-varies positively with farmers’ productivity and it is estimated to be r = 0.026, 0.54 and 0.741 (

p < 0.05). This suggests that when agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages (Knowledge, Acceptance and Behavioural Change) go up by one standard deviation, accounting methods will go up by 0.026, 0.54 and 0.741, respectively.

To re-examine the construct validity, discriminant validity was used. Discriminant validity decision role states that the square root of AVE for each construct should not be less than the correlation of that construct [

31]. The output of discriminant validity shows that the square root of AVE for each construct exceeds that construct’s correlation under consideration, as depicted in

Table 7.

4. Discussion

As highlighted in the introductory part of the study, three alternate hypotheses were formed to guide the study. They include: farmers’ knowledge of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages has significant influence on their productivity; farmers’ acceptance rate of agricultural radio programmes has significant influence on their agricultural yield; behavioural change as a result of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages has significant influence on farmers’ productivity.

Findings show that farmers’ knowledge of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages influences their productivity. R in the model shows the strength of the relationship. The R value is 0.677; this suggests a significant relationship between farmers’ knowledge of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages and farmers’ productivity, which affirms the first hypothesis. The R

2 depicts the proportion of farmers’ productivity variance that is predictable from farmers’ knowledge of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages. The R

2 value is 0.458 which, if expressed in percentage, is 45.8%. This indicates that the variance can explain 45.8% of the variance in farmers’ productivity in the farmers’ knowledge of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages. The coefficient table also shows the model that expresses how farmers’ knowledge of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages influences farmers’ productivity. The significance level below 0.05 implies statistical confidence of above 95%. This means that farmers’ knowledge of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages significantly influences farmers’ productivity. As the above, the alternate hypothesis was accepted and the null was rejected. Therefore, farmers’ knowledge of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages significantly influences farmers’ productivity. A study by [

32] pointed out that a good number of community radio listeners had a very high level of listening behaviours. The profile characteristics, namely time spent of household, farm activities, economic activities and traditional media exposure, correlated significantly with listening behaviour of community radio listeners and give credence to this study. Thus, it can be argued that farmers’ knowledge of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages has significant influence on their productivity.

Findings further show the influence of farmers’ acceptance rate of agricultural radio programmes on their agricultural output. R in the model shows the strength of the relationship. The R value is 0.702; this implies a tremendous significant relationship between farmers’ acceptance rate of agricultural radio programmes and their agricultural yield. The R2 depicts the variance in the agricultural return that is predictable from farmers’ acceptance rate of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages. The R2 value is 0.493, if expressed in percentage, is 49.3%. This signifies that the variance can explain 49.3% of the variance in agricultural yield in the farmers’ acceptance rate of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages.

Similarly, the coefficient table shows the model that expresses how farmers’ acceptance rate of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages influences agricultural yield. The significance level below 0.05 implies statistical confidence of above 95%. This means that farmers’ acceptance rate of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages significantly influences agricultural yield. As above, the alternate hypothesis was accepted, and the null was rejected Therefore, farmers’ acceptance rate of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages significantly influences agricultural yield. This finding aligns with [

33,

34] who concluded that attitudes towards farm extensive participation in farm broadcasts, belief in radio and knowledge about farm broadcasts had a significant relationship with dependent variables on the effectiveness of farm broadcast at the 1% level of probability.

A study conducted in Northern California by Jenkins and his contemporaries gave credence to this and showed that mass communication has supplied a lot of helpful agricultural information. The experience has been quite significant [

35]. Radio programmes are a powerful and effective medium for disseminating agricultural information and expertise in developing nations [

36]. According to [

37], the benefit of radio programmes as a means of communication is that its transmission, presentation and portability are cost effective. Radio can be an essential tool for teaching farmers if it attracts them to new programmes utilising modern farming techniques. However, to correctly understand and execute such programmes, indigenous language use is crucial in ensuring that farmers are educated on contemporary practices in agricultural development because the use of indigenous languages fosters an understanding of what is required [

38,

39]. As rural farmers participate in radio programmes, they become more exciting and efficient because of the sensation of ownership. This readily gets through the message and information. Reference [

40] confirms that information on enhanced agriculture, seed improvement, planting, agricultural forestry, improved harvesting methods, soil preservation, marketing, processing and diversification after harvest is key to agricultural development. Reference [

41] discovered that acceptance of radio programmes has contributed to strengthening social unity, improving communicative capacity, providing historical understanding, maintaining the environment and solving community issues. These findings affirm that farmers’ acceptance rate of agricultural radio programmes has significant influence on their agricultural yield as identified by this study.

The influence of farmers’ behavioural changes resulting from agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages on farmers’ productivity was shown in

Table 3. R in the model shows the strength of the relationship. The R value is 0.696; this suggests a highly significant association between farmers’ behavioural changes resulting from agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages and farmers’ productivity. The R

2 depicts the proportion of the farmers’ productivity variance that is predictable from farmers’ knowledge of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages. The R

2 value is 0.484 which, if expressed in percentage, is 48.4%. This indicates that the variance can explain 48.4% of the variance in farmers’ productivity in the farmers’ behavioural changes as a result of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages. Reference [

42] found that the respondents’ social participation was positively correlated with the respondents’ listening behaviour and affirms the findings of this study. This is because behavioural changes as a result of agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages influence farmer productivity.

Thus, the coefficient table shows the model that expresses how farmers’ behavioural changes resulting from agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages influence farmers’ productivity. The significance level below 0.05 implies statistical confidence of above 95%. This means that farmers’ behavioural changes resulting from agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages significantly influence farmers’ productivity. As above, the alternate hypothesis was accepted, and the null was rejected. Therefore, farmers’ behavioural changes resulting from agricultural radio programmes in indigenous languages significantly influence farmers’ productivity.