Caring for Things Helps Humans Grow: Effects of Courteous Interaction with Things on Pro-Environmental Behavior

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Interaction with Familiar Things and Consideration for Nature

1.2. Concerns and Values Related to PEB

1.3. Connectedness with Nature and Things

1.4. Interaction with Objects, PEB, and Well-Being

2. Overview of the Studies

3. Study 1

3.1. Method

Free Description Survey

3.2. Results

3.3. Method

Survey for Exploratory Factor Analysis

3.4. Results

3.5. Discussion

4. Study 2

4.1. Method

4.1.1. Participants and Procedure

4.1.2. Measures

4.2. Results

4.2.1. Selected Objects

4.2.2. Interaction with Objects and Connectedness

4.2.3. Correlation between Care and Learn for the Identified Object and for General Objects

4.3. Discussion

5. Study 3

5.1. Method

5.1.1. Participants and Procedure

5.1.2. Measures

5.2. Results

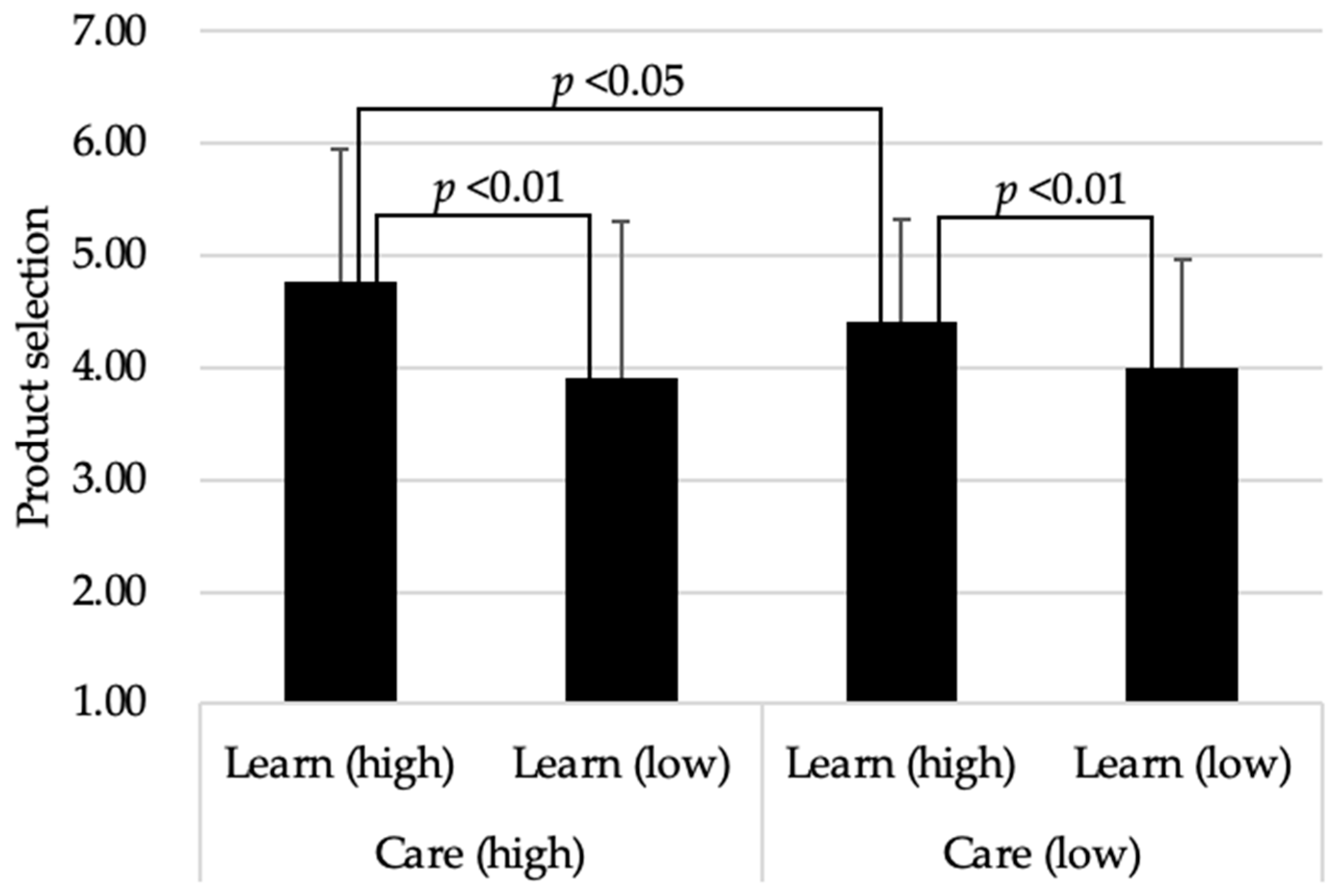

5.2.1. The Effect of Care and Learn on PEBs

5.2.2. The Relationship among Care, Learn, PEB, and Well-Being

5.3. Discussion

6. General Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mori, M.; Kamide, H. Robotics and the Teaching of the Buddha; Kosei-Shuppan: Tokyo, Japan, 2018. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Mori, M. The meaning of the robot-contest for the human education. J. Robot. Soc. Jpn. 2009, 27, 694–966. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Miceli, A.; Hagen, B.; Riccardi, M.P.; Sotti, F.; Settembre-Blundo, D. Thriving, Not Just Surviving in Changing Times: How Sustainability, Agility and Digitalization Intertwine with Organizational Resilience. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeble, B.R. The Brundtland report: ‘Our common future’. Med. War 1988, 4, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2015. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld/publication (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- Di Fabio, A.; Rosen, M.A. An Exploratory Study of a New Psychological Instrument for Evaluating Sustainability: The Sustainable Development Goals Psychological Inventory. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabio, A.; Rosen, M.A. Opening the Black Box of Psychological Processes in the Science of Sustainable Development: A New Frontier. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. Res. 2018, 2, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Fabio, A. Positive Healthy Organizations: Promoting Well-Being, Meaningfulness, and Sustainability in Organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Di Fabio, A. The Psychology of Sustainability and Sustainable Development for Well-Being in Organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations about the Sustainable Development Goals 2018. 2018. Available online: https://www.un.org/ (accessed on 2 April 2020).

- Schultz, P.W. Empathizing with nature: The effect of perspective taking on concern for environmental issues. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W. The structure of environmental concern: Concern for self, other people, and the biosphere. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schultz, P.W.; Shriver, C.; Tabanico, J.J.; Khazian, A.M. Implicit connections with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bruni, C.M.; Schultz, P.W. Implicit beliefs about self and nature: Evidence from an IAT game. J Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jugert, P.; Greenaway, K.H.; Barth, M.; Büchner, R.; Eisentraut, S.; Fritsche, I. Collective efficacy increases pro-environmental intentions through increasing self-efficacy . J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 48, 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabernero, C.; Hernandez, B. Self-efficacy and intrinsic motivation guiding environmental behavior. Environ. Behav. 2011, 43, 658–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, I.; Reynolds, D. Predicting green hotel behavioral intentions using a theory of environmental commitment and sacrifice for the environment. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 52, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnocky, S.; Stroink, M.; De Cicco, T. Self-construal predicts environmental concern, cooperation, and conservation. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinds, J.; Sparks, P. Engaging with the natural environment: The role of affective connection and identity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankel, S.; Sellmann-Risse, D.; Basten, M. Fourth graders’ connectedness to nature—Does cultural background matter? J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 66, 101347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; White, M.P.; Hunt, A.; Richardson, M.; Pahl, S.; Burt, J. Nature contact, nature connectedness and associations with health, wellbeing and pro-environmental behaviours. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 68, 1–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen-Hsuan Cheng, J.; Monroe, M.C. Connection to nature: Children’s affective attitude toward nature. Environ. Behav. 2012, 44, 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grønhøj, A.; Thøgersen, J. Why young people do things for the environment: The role of parenting for adolescents’ motivation to engage in pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 54, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, C.; Vagias, W.M.; DeWard, S.L. Exploring additional determinants of environmentally responsible behavior: The influence of environmental literature and environmental attitudes. Environ. Behav. 2010, 42, 420–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T. The value basis of environmental concern. J. Soc. Issues 1994, 50, 65–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.H. Value orientations: Measurement, antecedents and consequences across nations. In Measuring Attitudes Cross-Nationally: Lessons from the European Social Survey; Jowell, R., Roberts, C., Fitzgerald, R., Eva, G., Eds.; Sage Publications, Ltd.: London, UK, 2007; pp. 169–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutte, N.S.; Malouff, J.M. Mindfulness and connectedness to nature: A meta-analytic investigation. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018, 127, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Geng, L.; Schultz, P.W.; Zhou, K.; Xiang, P. The effects of mindfulness on pro-environmental behavior: A self-expansion perspective. Conscious. Cogn. 2017, 51, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, A.; Aron, E.N.; Smollan, D. Inclusion of other in the self scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 63, 596–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.; Czellar, S. Where do biospheric values come from? A connectedness to nature perspective. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 52, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dong, X.; Liu, S.; Li, H.; Yang, Z.; Liang, S.; Deng, N. Love of nature as a mediator between connectedness to nature and sustainable consumption behavior. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmi, N. Caring about tomorrow: Future orientation, environmental attitudes and behaviors. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 19, 430–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prati, G.; Albanesi, C.; Pietrantoni, L. Social Well-Being and Pro-Environmental Behavior: A Cross-Lagged Panel Design. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2017, 23, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.; Kasser, T. Are psychological and ecological well-being compatible? The role of values, mindfulness, and lifestyle. Soc. Indic. Res. 2005, 74, 349–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, L.R.; Lasonde, K.M.; Weiss, J. The relationship between environmental issue involvement and environmentally-conscious behavior: An exploratory study. Adv. Consum. Res. 1996, 23, 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Sudbury-Riley, L.; Kohlbacher, F. Ethically minded consumer behavior: Scale review, development, and validation. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 2697–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ojedokun, O. Development and Psychometric Evaluation of the Littering Prevention Behavior Scale. Ecopsychology 2016, 8, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Gouveia, V.V.; Cameron, L.D.; Tankha, G.; Schmuck, P.; Franěk, M. Values and their relationship to environmental concern and conservation behavior. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 2005, 36, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armel, K.C.; Yan, K.; Todd, A.; Robinson, T.N. The Stanford Climate Change Behavior Survey (SCCBS): Assessing greenhouse gas emissions-related behaviors in individuals and populations. Clim. Chang. 2011, 109, 671–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, M.P.; Ward, M.P. Ecology: Let’s hear from the people: An objective scale for the measurement of ecological attitudes and knowledge. Am. Psychol. 1973, 28, 583–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maloney, M.P.; Ward, M.P.; Braucht, G.N. A revised scale for the measurement of ecological attitudes and knowledge. Am. Psychol. 1975, 30, 787–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilikidou, I.; Adamson, I.; Sarmaniotis, C. The measurement instrument of ecologically conscious consumer behaviour. MEDIT 2002, 1, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, L.R.; Stedman, R.C.; Cooper, C.B.; Decker, D.J. Understanding the multi-dimensional structure of pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brick, C.; Sherman, D.K.; Kim, H.S. “Green to be seen” and “brown to keep down”: Visibility moderates the effect of identity on pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 226–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey, P.J.; Scott, K. Environmental concern and behaviour in an Australian sample within an ecocentric–anthropocentric framework. Aust. J. Psychol. 2006, 58, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.H.; Jan, F.H.; Yang, C.C. Conceptualizing and measuring environmentally responsible behaviors from the perspective of community-based tourists. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 454–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, F.; Dewitte, S. Measuring pro-environmental behavior: Review and recommendations. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 63, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W. Inclusion with nature: Understanding the psychology of human-nature interactions. In Psychology of Sustainable Development; Schmuck, P., Schultz, P.W., Eds.; Kluwer: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 61–78. [Google Scholar]

- Horike, K. A Preliminarily Study for the Individual Differences in Sustainable Mind and Behavior. European Congress on Psychology; University of Trieste: Trieste, Italy, 2012; p. 206. [Google Scholar]

- Bechtel, R.B.; Corral-Verdugo, V. Happiness and Sustainable Behavior. In Psychological Approaches to Sustainability; Corral, V., García, C., Frías, M., Eds.; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 433–450. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The Satisfaction with Life Scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, A.; Glickauf-Hughes, C. Object relations and addiction: The role of “transmuting externalizations”. J. Contemp. Psychother. 1992, 22, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, A. Computer and Video Game Addiction—A Comparison between Game Users and Non-Game Users. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2010, 36, 268–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hargreaves, T. Practicing behaviour change: Applying social practice theory to proenvironmental behaviour change. J. Consum. Cult. 2011, 11, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazar, N.; Zhong, C.-B. Do green products make us better people? Psychol. Sci. 2010, 21, 494–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urban, J.; Bahnik, S.; Kohlová, M.B. Green consumption does not make people cheat: Three attempts to replicate moral licensing effect due to pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 63, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markus, H.R.; Kitayama, S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991, 98, 224–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, T.; Nisbett, R.E. Attending holistically versus analytically: Comparing the context sensitivity of Japanese and Americans. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 81, 922–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, M.; Culture, Learning, and Development and the Natural. World: The Influences of Situative Perspectives. Educ. Psychol. 2015, 50, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourey, J.A.; Oyserman, D.; Yoon, C. One without the other: Seeing relationships in everyday objects. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 2, 1615–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Available online: https://www.stat.go.jp/data/roudou/sokuhou/tsuki/index.html (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Winner, L. The Whale and the Reactor; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Latour, B. We Have Never Been Modern; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mammen, J. A New Logical Foundation for Psychology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeek, P.-P. Moralizing Technology: Understanding and Designing the Morality of Things; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA; London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

| Category | Examples of Obtained Descriptions | N | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maintenance | C: After using my brush and my ink stone, I wash them clean. | 8 | 67 |

| T: After using the bowls, I dry them well and then put them back in the right place in the right order. | 8 | ||

| F: I wipe the scissors’ blade with a dry cloth after use to prevent it from rusting. | 9 | ||

| J: I always keep my Judo uniform and mats clean. | 6 | ||

| K: When a bamboo sword is flaked, I cut it off. | 18 | ||

| W: I clean and manage (computer, shaver, etc.) daily. | 18 | ||

| Change in view of things | C: I came to value things. | 2 | 44 |

| T: I learned the importance of things in general. | 4 | ||

| F: I understand that if I handle it carefully, I can use it for a long time. | 8 | ||

| J: I now know to appreciate it including other things. | 1 | ||

| K: I learned to appreciate it as well as other things. | 5 | ||

| W: If I take care of glasses, they will last longer. | 24 | ||

| Treatment | C: I use it so that the tip of the brush does not have a strange shape. | 2 | 39 |

| T: I do not wear a ring so as not to damage the tea ware. | 8 | ||

| F: I treat the vase with care so as not to break it. | 5 | ||

| J: I take care of how to move my legs on the tatami mat. | 1 | ||

| K: (No applicable answer) | 0 | ||

| W: I take care not to get the suit dirty. | 23 | ||

| Change in view of the self or humans | C: I learned that treating tools carefully is reflected in calligraphy works. | 7 | 38 |

| T: I got to know about respect for each other. | 12 | ||

| F: I found that those who treat their tools with care improved quickly. | 8 | ||

| J: I learned self-control. | 3 | ||

| K: I learned not to give up and to get things done to the end. | 6 | ||

| W: I acquired new knowledge. | 2 | ||

| Other | F: I prepared flowers so that they are easy to arrange. J: I prepared many Judo uniforms and belts. K: Safety. W: I have come to save money. | 8 | |

| Total | 196 |

| Items | Factor 1: Learn | Factor 2: Care |

|---|---|---|

| I have learned how to be nice to other people using the tool (object). | 0.96 | −0.09 |

| Using the tool (object) builds my mental strength. | 0.94 | −0.06 |

| I have learned how to control myself by using the tool (object). | 0.92 | −0.08 |

| I have built a respectful attitude toward objects by using the tool (object). | 0.91 | −0.01 |

| Using the tool (object), I have come to treat other objects thoughtfully. | 0.90 | 0.03 |

| I have come to use other tools carefully by using the tool (object). | 0.84 | 0.10 |

| Using the tool (object), I have come to appreciate objects more. | 0.78 | 0.13 |

| Using this tool (object), I have acquired good manners of physical operation toward other objects. | 0.76 | 0.07 |

| I make it a point to handle the tool (object) carefully. | −0.03 | 0.93 |

| I take great care not to break the tool (object). | −0.07 | 0.91 |

| I try not to handle the tool (object) roughly. | −0.04 | 0.88 |

| After using the tool (object), I keep it tidy and in complete order. | −0.09 | 0.85 |

| I keep things organized when using the tool (object). | 0.04 | 0.83 |

| I try to keep the tool (object) clean. | 0.07 | 0.80 |

| I use the tool (object) neatly so that it does not get dirty. | 0.07 | 0.78 |

| I try to use the tool (object) gently. | 0.15 | 0.77 |

| Inter-factor correlation | Factor 1 | Factor 2 |

| Factor 1 | 1.00 | 0.52 |

| Factor 2 | 0.52 | 1.00 |

| Reliability | 0.97 | 0.95 |

| Mean (SD) | 4.37 (1.36) | 5.24 (1.17) |

| Learn for an Identified Object | Care for General Objects | Learn for General Objects | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Care for an identified object | 0.45 ** | 0.73 ** | 0.49 ** |

| Learn for an identified object | 0.39 ** | 0.75 ** | |

| Care for general objects | 0.64 ** |

| Factor (Alpha Reliability; Factor Contribution) | Items |

|---|---|

| General PEB (0.89; 6.99) Mean = 4.40 (SD = 1.28) |

|

| Social life (0.91; 10.90) Mean = 3.79 (SD = 1.10) |

|

| Product selection (0.82; 10.63) Mean = 4.34 (SD = 1.16) |

|

| Power saving (0.83; 8.91) Mean = 4.73 (SD = 1.09) |

|

| Waste avoidance (0.84; 8.63) Mean = 5.15 (SD = 0.91) |

|

| Disposal avoidance (0.86; 7.89) Mean = 4.60 (SD = 1.58) |

|

| Recycling (0.89; 6.65) Mean = 3.78 (SD = 1.53) |

|

| Variables | Care | Learn | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | High | Low | |||

| General PEB | M | 4.70 | 4.10 | 4.70 | 4.10 | 4.40 |

| SD | 1.37 | 1.11 | 1.18 | 1.24 | 1.28 | |

| Social life | M | 3.96 | 3.62 | 3.96 | 3.62 | 3.79 |

| SD | 1.19 | 0.96 | 1.05 | 1.01 | 1.10 | |

| Product selection | M | 4.56 | 4.12 | 4.56 | 4.12 | 4.34 |

| SD | 1.29 | 0.97 | 1.13 | 1.09 | 1.16 | |

| Power saving | M | 5.01 | 4.44 | 5.02 | 4.40 | 4.73 |

| SD | 1.13 | 0.96 | 1.03 | 1.06 | 1.09 | |

| Waste avoidance | M | 5.56 | 4.73 | 5.49 | 4.77 | 5.15 |

| SD | 0.78 | 0.85 | 0.80 | 0.88 | 0.91 | |

| Disposal avoidance | M | 4.86 | 4.32 | 4.91 | 4.24 | 4.60 |

| SD | 1.71 | 1.37 | 1.51 | 1.58 | 1.58 | |

| Recycling | M | 3.90 | 3.66 | 4.05 | 3.48 | 3.78 |

| SD | 1.70 | 1.33 | 1.59 | 1.41 | 1.53 | |

| Predictors | df | Sum Sq | Mean Sq | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General PEB | Care | 1 | 7.11 | 7.11 | 4.91 | 0.03 |

| Learn | 1 | 62.83 | 62.83 | 43.41 | 0.00 | |

| Care*Learn | 1 | 5.85 | 5.85 | 4.04 | 0.05 | |

| Residuals | 596 | 862.67 | 1.45 | |||

| Social life | Care | 1 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.78 |

| Learn | 1 | 63.76 | 63.76 | 60.62 | 0.00 | |

| Care*Learn | 1 | 13.71 | 13.71 | 13.04 | 0.00 | |

| Residuals | 596 | 626.96 | 1.05 | |||

| Product selection | Care | 1 | 2.15 | 2.15 | 1.75 | 0.19 |

| Learn | 1 | 46.27 | 46.27 | 37.72 | 0.00 | |

| Care*Learn | 1 | 5.44 | 5.44 | 4.43 | 0.04 | |

| Residuals | 596 | 731.15 | 1.23 | |||

| Power saving | Care | 1 | 14.43 | 14.43 | 13.55 | 0.00 |

| Learn | 1 | 24.66 | 24.66 | 23.17 | 0.00 | |

| Care*Learn | 1 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.56 | 0.46 | |

| Residuals | 596 | 634.48 | 1.07 | |||

| Waste avoidance | Care | 1 | 45.14 | 45.14 | 72.11 | 0.00 |

| Learn | 1 | 21.63 | 21.63 | 34.55 | 0.00 | |

| Care*Learn | 1 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.53 | 0.47 | |

| Residuals | 596 | 373.10 | 0.63 | |||

| Disposal avoidance | Care | 1 | 8.40 | 8.40 | 3.56 | 0.06 |

| Learn | 1 | 35.25 | 35.25 | 14.93 | 0.00 | |

| Care*Learn | 1 | 3.73 | 3.73 | 1.58 | 0.21 | |

| Residuals | 596 | 1407.25 | 2.36 | |||

| Recycling | Care | 1 | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.17 | 0.68 |

| Learn | 1 | 42.79 | 42.79 | 18.94 | 0.00 | |

| Care*Learn | 1 | 8.75 | 8.75 | 3.87 | 0.05 | |

| Residuals | 596 | 1346.56 | 2.26 |

| Predictors | df | Sum Sq | Mean Sq | F | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General PEB | age | 1 | 29.24 | 29.24 | 21.27 | 0.00 |

| gender | 1 | 10.03 | 10.03 | 7.30 | 0.01 | |

| occupation or working status | 1 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.43 | 0.51 | |

| Care | 1 | 7.15 | 7.15 | 5.21 | 0.02 | |

| Learn | 1 | 51.76 | 51.76 | 37.67 | 0.00 | |

| Care*Learn | 1 | 4.89 | 4.89 | 3.56 | 0.06 | |

| Residuals | 593 | 814.93 | 1.37 | |||

| Social life | age | 1 | 25.99 | 25.99 | 26.00 | 0.00 |

| gender | 1 | 8.95 | 8.95 | 8.96 | 0.00 | |

| occupation orworking status | 1 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.65 | 0.42 | |

| Care | 1 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.81 | |

| Learn | 1 | 52.91 | 52.91 | 52.92 | 0.00 | |

| Care*Learn | 1 | 12.54 | 12.54 | 12.54 | 0.00 | |

| Residuals | 593 | 592.90 | 1.00 | |||

| Product selection | age | 1 | 19.32 | 19.32 | 16.96 | 0.00 |

| gender | 1 | 31.39 | 31.39 | 27.55 | 0.00 | |

| occupation orworking status | 1 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.80 | |

| Care | 1 | 1.86 | 1.86 | 1.64 | 0.20 | |

| Learn | 1 | 39.14 | 39.14 | 34.35 | 0.00 | |

| Care*Learn | 1 | 5.04 | 5.04 | 4.42 | 0.04 | |

| Residuals | 593 | 675.67 | 1.14 | |||

| Power saving | age | 1 | 14.85 | 14.85 | 14.78 | 0.00 |

| gender | 1 | 20.83 | 20.83 | 20.73 | 0.00 | |

| occupation orworking status | 1 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.79 | |

| Care | 1 | 13.85 | 13.85 | 13.78 | 0.00 | |

| Learn | 1 | 20.15 | 20.15 | 20.05 | 0.00 | |

| Care*Learn | 1 | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.47 | 0.49 | |

| Residuals | 593 | 595.87 | 1.01 | |||

| Waste avoidance | age | 1 | 7.96 | 7.96 | 13.46 | 0.00 |

| gender | 1 | 5.93 | 5.93 | 10.03 | 0.00 | |

| occupation orworking status | 1 | 1.65 | 1.65 | 2.79 | 0.10 | |

| Care | 1 | 44.39 | 44.39 | 75.07 | 0.00 | |

| Learn | 1 | 18.40 | 18.40 | 31.11 | 0.00 | |

| Care*Learn | 1 | 0.22 | 0.22 | 0.36 | 0.55 | |

| Residuals | 593 | 350.64 | 0.59 | |||

| Disposal avoidance | age | 1 | 16.11 | 16.11 | 7.90 | 0.01 |

| gender | 1 | 160.84 | 160.84 | 78.83 | 0.00 | |

| occupation orworking status | 1 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.46 | 0.50 | |

| Care | 1 | 6.22 | 6.22 | 3.05 | 0.08 | |

| Learn | 1 | 31.20 | 31.20 | 15.30 | 0.00 | |

| Care*Learn | 1 | 4.08 | 4.08 | 2.00 | 0.16 | |

| Residuals | 593 | 1209.84 | 2.04 | |||

| Recycling | age | 1 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.32 | 0.57 |

| gender | 1 | 8.95 | 8.95 | 3.99 | 0.05 | |

| occupation orworking status | 1 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.24 | 0.63 | |

| Care | 1 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.25 | 0.62 | |

| Learn | 1 | 41.40 | 41.40 | 18.44 | 0.00 | |

| Care*Learn | 1 | 8.74 | 8.74 | 3.89 | 0.05 | |

| Residuals | 593 | 1331.78 | 2.25 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kamide, H.; Arai, T. Caring for Things Helps Humans Grow: Effects of Courteous Interaction with Things on Pro-Environmental Behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3969. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073969

Kamide H, Arai T. Caring for Things Helps Humans Grow: Effects of Courteous Interaction with Things on Pro-Environmental Behavior. Sustainability. 2021; 13(7):3969. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073969

Chicago/Turabian StyleKamide, Hiroko, and Tatsuo Arai. 2021. "Caring for Things Helps Humans Grow: Effects of Courteous Interaction with Things on Pro-Environmental Behavior" Sustainability 13, no. 7: 3969. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13073969