Empirical Analysis of Factors Affecting the Bilateral Trade between Mongolia and China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

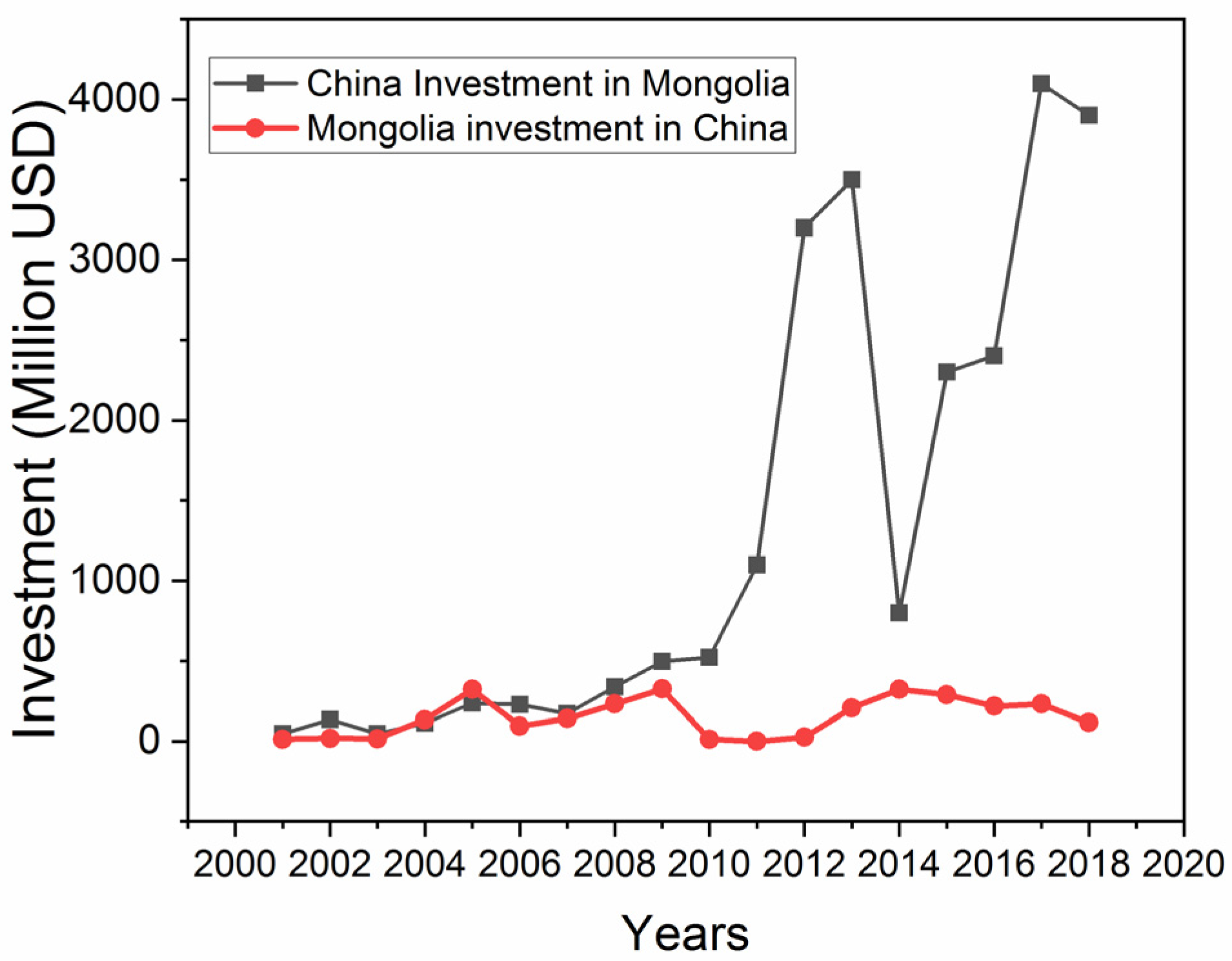

China-Mongolia Economic and Trade Partnership

3. Empirical Model and Variables

3.1. The Model

- = Exports of i country to j country in t period (Mongolia Exports to China);

- = GDP of i country in t period (Mongolia);

- = GDP of j country in t period (China);

- = country i Population in t period (Mongolia);

- = country j Population in t period (China);

- = Distance between China and Mongolia;

- = Cultural Distance;

- = number of regional agreements of China and Mongolia;

- = trade integration dummy for trade agreement between china and Mongolia;

- = Tariffs imposed on Mongolia exports by China;

- = Trade Facilitation Index of China;

- = Mongolia-China Trade Cost index;

- = error term.

3.2. Sample Size, Variables, and Data Source

- (1)

- Exports: Total exports from country i Mongolia to trading partner country j China is our dependent variable. The data on Mongolia exports to China were gained from the World Integrated Trade Solution database for the period 1996–2019.

- (2)

- Gross Domestic Product (GDP): The GDP of exporting country and trading partners represents both the productive and consumption capacity that determines largely the trade flows among them. The GDP of the country represents the market size of the country and it is expected that the coefficient of GDP of both exporting and trading partner country is positive because the trade flows between countries increases with increase GDP of countries. The data on GDP were obtained from the World Bank database.

- (3)

- Population: Population is helpful to calculate the size of the market of each country, which is affecting international trade. In our study, we used both exporting country and trading partner total population, the expected sign of coefficient is negative. The data on population were obtained from the World Bank database.

- (4)

- Geographical Distance: Usually, the higher the geographical distance among two countries, there will be more risk of trade and cost of transportation. The higher cost and risk is not more advantageous for realization of trade collaboration among the countries. Agreeing to the distance calculation method described in previous study [38], the formula of relative distance is:where is the geographical distance between i country and its transaction partner j state in year t. signifies the GDP of country j for the year t. is the gross domestic product (GDP) of country i in year t. is the absolute distance between capitals of two countries (i and j). The GDP data of country i and j were gained from the World Bank database for the period 1996–2019. The distance data between countries i and j were obtained from the Research and Expertise on World Economy (CEPII) database.

- (5)

- Cultural Distance: It means alterations in ideology, such as morals or beliefs of two countries (i and j). Usually, there is inverse relationship between cultural differences and trade collaboration between two countries. The smaller the difference between two countries, the sturdier is the sense of distinctiveness and trust. Thus, this can create the greater possibility of trade cooperation between the trading partner’s countries. However, in order to calculate the cultural distance between Mongolia and China, we adopted the cultural data delivered by Hofstede. Following the methodology of Qi et al. [39], the formula of cultural distance is:where j is trading companion country i.e., China. denotes the cultural distance between Mongolia and its trading companion China. is the index of cultural dimension i of trading partner j and is the cultural dimension index i of Mongolia. is the cultural dimension variance index i, and n denotes the number of cultural dimensions. Generally, the dataset contain six dimensions, including power distance, masculinity, individualism, uncertainty avoidance, long term orientation, and indulgence (Figure 2). represents the number of years from the time when the Belt and Road country j recognized diplomatic relations with China in year t.

- (6)

- Trade agreements Dummy: This study used two regional trade integration dummies; (1) number of trade agreement of China and Mongolia during the sample time period with the rest of the world and trade agreements between China Mongolia. If the country i and j are members of the signed agreement = 1 otherwise 0.

- (7)

- Tariffs (Traiffj): The impact of tariffs on trade flows are essential and significant potential large barriers to trade. An increase in tariffs on exports and imports reduce overall trade due to raising the price of goods relative to domestic products. In this study, we used the tariffs on exports of Mongolia imposed by the trading partner China. The data on tariffs were obtained from the World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS) database for the period 1996–2019.

- (8)

- Trade Facilitation Index of China (TWTFIj): Trade facilitation is a concept used to eliminate barriers to flows of trade and reduce trade costs (OECD/WTO, 2015) [40]. The WTO (2015) define it as the explanation and coordination of the universal trade procedure. Trade facilitation is simply relating to the border procedures, including the customs and procedures of port as well as transport formalities. In this study, we used the trade facilitation as quality, clearness, and efficacy of border administration of the trading partner country, China. We used the indicators composed by the World Economic Forum (WEF) Enabling Trade Index (ETI). These indicators were evaluated by different data sources including the Doing Business and logistic performance of the World Bank and survey of WEF [41]. Definition of variables and data sources are presented in Table 1. The main indicators of the trade facilitation index are shown in Table 2. The missing data were collected from the different reports of IMF, WB, and WEF reports over the period 1996–2019.

- (9)

- Mongolia-China Trade Cost (MCTCIij): In this study, we generated the index of the Mongolia China trade cost index by using the principle component analysis (PCA) [42]. The data were collected from the World Bank Doing Business Database. The missing value are filled by mean interpolation method. This database provides comprehensive country data on relevant information related to trade cost, including time to exports, cost to exports, and the number of documents required to exports, time to imports, cost to imports, and documents required to exports. Using the PCA approach, composite Mongolia China trade cost index is created. The indicators of trade cost index and Mongolian China trade cost relationship were determined and shown in Table 2.

3.3. Data Description Empirical Analysis

4. Results of Empirical Analysis and Discussion

4.1. Principle Component Analysis (PCA)

4.2. Unit Root Test

4.3. Bound Test for the Level Relationship

4.4. Long Run and Short Run Coefficients

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Policy Implementation

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Soni, S.K. China–Mongolia–Russia economic corridor: Opportunities and challenges. In China’s Global Rebalancing and the New Silk Road; Deepak, B.R., Ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 101–117. [Google Scholar]

- Mavidkhaan, B. Research on China Mongolia economic and trade cooperaton. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Econ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munkherdene, G.; Sneath, D.J.C.A. Enclosing the gold-mining commons of Mongolia. Curr. Anthropol. 2018, 59, 814–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Tavitiyaman, P.; Chen, D. How “belt and road” initiative affects tourism demand in China: Evidence from China-Mongolia-Russia economic corridor. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2020, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Jia, J.; Liu, H.; Lin, Z. Relative importance of climate change and human activities for vegetation changes on China’s silk road economic belt over multiple timescales. Catena 2019, 180, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugesan, S. New perspectives on China’s foreign and trade policy. Asian J. Ger. Eur. Stud. 2018, 3, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavidkhaan, B. Empirical analysis of impacts on China and Mongolian transport service trade of international competitiveness. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Econ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasrullah, M.; Chang, L.; Khan, K.; Rizwanullah, M.; Zulfiqar, F.; Ishfaq, M. Determinants of forest product group trade by gravity model approach: A case study of China. For. Policy Econ. 2020, 113, 102117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.E.; van Wincoop, E. Gravity with gravitas: A solution to the border puzzle. Am. Econ. Rev. 2003, 93, 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yao, X.; Yasmeen, R.; Li, Y.; Hafeez, M.; Padda, I.U. Free trade agreements and environment for sustainable development: A gravity model analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, E.; Lu, M.; Chen, Y. Analysis of China’s importance in “belt and road initiative” trade based on a gravity model. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, K. Bayesian model averaging and jointness measures: Theoretical framework and application to the gravity model of trade. Stat. Trans. N. Ser. 2017, 18, 393–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beck, K. What drives international trade? Robust analysis for the European Union. J. Int. Stud. 2020, 13, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debaere, P. Relative factor abundance and trade. J. Polit. Econ. 2003, 111, 589–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gosh, S.; Yamarik, S. Are Regional trading arrange& ments trade creating? An application of extreme bounds analysis. J. Int. Econ. 2004, 63, 369–395. [Google Scholar]

- Yamarik, S.; Ghosh, S. A sensitivity analysis of the gravity model. Int. Trade J. 2005, 19, 83–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrère, C.; Masood, M. Cultural proximity: A source of trade flow resilience? World Econ. 2018, 41, 1812–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.R.; Weinstein, D.E. An account of global factor trade. Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 1423–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, C.; Wei, Y.; Liu, X. Determinants of bilateral trade flows in OECD countries: Evidence from gravity panel data models. World Econ. 2010, 33, 894–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frankel, J.; Rose, A. An estimate of the effect of common currencies on trade and income. Quart. J. Econ. 2002, 117, 437–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rose, A.K.; Van Wincoop, E. National money as a barrier to international trade: The real case for currency union. Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frankel, J.; Stein, E.; Wei, S.-J. Trading blocs and the Americas: The natural, the unnatural, and the super-natural. J. Dev. Econ. 1995, 47, 61–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, H.L.; Linders, G.J.; Rietveld, P.; Subramanian, U.J.K. The institutional determinants of bilateral trade patterns. Kyklos 2004, 57, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, M.W.; Shambaugh, J.C. Fixed exchange rates and trade. J. Int. Econ. 2006, 70, 359–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCallum, J. National borders matter: Canada-US regional trade patterns. Am. Econ. Rev. 1995, 85, 615–623. [Google Scholar]

- Shahriar, S.; Qian, L.; Kea, S.; Abdullahi, N.M. The gravity model of trade: A theoretical perspective. Rev. Innov. Compet. J. Econ. Soc. Res. 2019, 5, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, I.H.; Wall, H.J. qControlling for heterogeneity in gravity models of trade and integration, rFederal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Rev. 2005, 87, 49o63. [Google Scholar]

- Banik, B.; Roy Chandan, K. Effect of exchange rate uncertainty on bilateral trade performance in SAARC countries: A gravity model analysis. Int. Trade Polit. Dev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahniser, S.S.; Pick, D.; Pompelli, G.; Gehlhar, M.J. Regionalism in the western hemisphere and its impact on US agricultural exports: A gravity-model analysis. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2002, 84, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundmark, R. Analysis and projection of global iron ore trade: A panel data gravity model approach. Min. Econ. 2018, 31, 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Buongiorno, J. Gravity models of forest products trade: Applications to forecasting and policy analysis. Forestry 2016, 89, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M. Intensification of geo-cultural homophily in global trade: Evidence from the gravity model. Soc. Sci. Res. 2011, 40, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.A. Imagined territory: The Republic of China’s 1955 veto of Mongolian membership in the United Nations. J. Am. East Asian Relat. 2018, 25, 263–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponka, T.; Ponomarenko, L.; Belchenko, A.; Li, X. Relations between China and Mongolia: Cultural and educational dimensions. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Contemporary Education, Social Sciences and Ecological Studies (CESSES 2019), Moscow, Russia, 5–6 June 2019; pp. 1102–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Dorj, T.; Yavuuhulan, D. Mongolian economic development strategy. Int. J. Asian Manag. 2003, 2, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeves, J. Mongolia’s place in China’s periphery diplomacy. In International Relations and Asia’s Northern Tier: Sino-Russia Relations, North Korea, and Mongolia; Rozman, G., Radchenko, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 175–189. [Google Scholar]

- Enkhbold, V.; Nomintsetseg, U.-O. Analyzing the impacts of Mongolia’s trade costs. Northeast Asian Econ. Rev. 2016, 4, 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Soloaga, I.; Wintersb, L.A. Regionalism in the nineties: What effect on trade? N. Am. J. Econ. Financ. 2001, 12, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Li, L.; Yang, L. Location choice of Chinese OFDI: Based on the threshold effect and test of cultural distance. J. Int. Trade 2012, 12, 137–147. [Google Scholar]

- World Trade Organization. Aid for Trade at a Glance 2015: Reducing Trade Costs for Inclusive, Sustainable Growth; OECD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hanouz, M.D.; Geiger, T.; Doherty, S. The Global Enabling Trade Report 2014; WEF: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Li, F.; Liu, Y.; Cheng, B. An Assessment of trade facilitation’s impacts on China’s forest product exports to countries along the “belt and road” based on the perspective of ternary margins. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, C.-Y.; Lai, A.-C.; Wang, Z.-A.; Hsu, Y.-C. The preliminary effectiveness of bilateral trade in China’s belt and road initiatives: A structural break approach. Appl. Econ. 2019, 51, 3890–3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanh, S.D.; Canh, N.P.; Doytch, N. Asymmetric effects of U.S. monetary policy on the U.S. bilateral trade deficit with China: A Markov switching ARDL model approach. J. Econ. Asymmet. 2020, 22, e00168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.M.; Thai, V.V.; Vu, T.P. Port service quality (PSQ) and customer satisfaction: An exploratory study of container ports in Vietnam. Marit. Bus. Rev. 2020, 6, 72–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, J.; Morris, S.; Portelance, G. Examining the debt implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a policy perspective. J. Infrastruct. Policy Dev. 2019, 3, 139–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Definition | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Importing country population in million at time t | WB | |

| Exporting country population in million at time t | WB | |

| Importing country GDP measured in million US$ at time t | WB | |

| Exporting country GDP measured in million US$ at time t | WB | |

| Geographical distance from exporting country to importing country in Kilometer | CEPII | |

| Cultural Distance | Hofstede Database | |

| Regional trade agreement by the importing and exporting country in numbers | RTAD-WTO | |

| Trade agreements between i and j country | RTAD-WTO | |

| (%) | Percentage of tariffs imposed by the importing country | WITS |

| Mongolia China trade cost total Index | ESCAP-WBDBD | |

| Trade Facilitation index | ESCAP-WBDBD |

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 13.879 | 1.388 | 11.238 | 15.688 | |

| 24 | 20.998 | 0.041 | 20.920 | 21.058 | |

| 24 | 14.796 | 0.105 | 14.656 | 14.987 | |

| 24 | 29.142 | 0.638 | 28.115 | 30.077 | |

| 24 | 22.609 | 0.485 | 21.955 | 23.365 | |

| 24 | 13.922 | 0.156 | 13.573 | 14.124 | |

| 24 | 0.126 | 0.132 | 0.133 | 0.131 | |

| 24 | 10.669 | 3.264 | 6.389 | 18.223 | |

| (numbers) | 24 | 2.125 | 1.825 | 0.000 | 6 |

| (dummy) | 24 | 0.542 | 0.509 | 0.000 | 1 |

| ASEAN (dummy) | 24 | 0.791 | 0.414 | 0 | 1 |

| GFC (dummy) | 24 | 0.125 | 0.337 | 0 | 1 |

| Trade Facilitation Index Indicators | |||||

| TF_1 | 24 | 3.186 | 0.505 | 2.16 | 3.67 |

| TF_2 | 24 | 3.209 | 0.434 | 2.16 | 3.62 |

| TF_3 | 24 | 3.039 | 0.554 | 2.12 | 3.7 |

| TF_4 | 24 | 2.923 | 0.385 | 2.19 | 3.31 |

| TF_5 | 24 | 3.375 | 0.573 | 2.33 | 3.91 |

| TF_6 | 24 | 3.177 | 0.530 | 2.18 | 3.75 |

| TF_7 | 24 | 3.819 | 0.783 | 2.45 | 4.60 |

| Mongolia China Trade Cost Indicators | |||||

| TRC_ex1 | 24 | 22.917 | 2.320 | 21 | 26 |

| TRC_ex2 | 24 | 96.465 | 0.786 | 95.177 | 97.9 |

| TRC_ex3 | 24 | 35.060 | 2.094 | 33.333 | 37.9 |

| TRC_im1 | 24 | 26.000 | 2.341 | 24 | 29 |

| TRC_im2 | 24 | 96.185 | 1.204 | 94.174 | 98.6 |

| TRC_im3 | 24 | 74.546 | 3.704 | 69.231 | 77.70 |

| Principle Component Analysis of Trade Facilitation Index | |||||

| Eigen Values | Proportion Explained | Primary Variables | Eigen Vectors | Correlation Coefficients | |

| Trade Facilitation Index | 7.81755 | 0.9772 | (i) Ability to track and trace consignments | 0.3527 | 0.9861 |

| (ii) Competence and quality of logistics services | 0.3489 | 0.9757 | |||

| (iii) Ease of arranging competitively priced shipments | 0.3544 | 0.9910 | |||

| (iv) Efficiency of customs clearance process | 0.3561 | 0.9956 | |||

| (v) shipments reach consignee within scheduled or expected time | 0.3493 | 0.9766 | |||

| (vi) Quality of trade and transport-related infrastructure | 0.3539 | 0.9895 | |||

| (vii) Quality of port infrastructure | 0.3561 | 0.9956 | |||

| Principle Component Analysis of Mongolia China Trade Cost | |||||

| Eigen Values | Proportion Explained | Primary Variables | Eigen Vectors | Correlation Coefficients | |

| Trade Cost Index | 2.17226 | 0.6954 | (i) Time to exports | 0.4583 | 0.9361 |

| (ii) Cost to export | 0.3661 | 0.7477 | |||

| (iii) Number of documents required to exports | 0.4714 | 0.9628 | |||

| (iv) Time to imports | 0.471 | 0.962 | |||

| (v) Cost to imports | 0.4529 | 0.9252 | |||

| (vi) Number of documents required to imports | −0.0826 | −0.1686 | |||

| Level | First Difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | Trend and Intercept | Intercept | Trend and Intercept | Decision | |

| 0.469 | −2.336 | −7.126 | −6.821 | ||

| (0.982) | (0.400) | (0.000) ** | (0.000) *** | I(1) | |

| −0.429 | −2.297 | −2.432 | −2.337 | ||

| (0.886) | (0.416) | (0.146) | (0.097) * | I(1) | |

| 1.718 | −3.609 | −2.740 | −3.751 | ||

| (0.999) | (0.055) ** | (0.086) ** | (0.047) ** | I(0) | |

| −1.322 | −1.269 | −1.191 | −1.546 | ||

| (0.601) | (0.869) | (0.659) | (0.081) * | I(1) | |

| 0.653 | −3.048 | −3.241 | −3.161 | ||

| (0.988) | (0.143) | (0.032) * | (0.119) | I(1) | |

| −2.831 | −2.749 | −4.354 | −4.213 | ||

| (0.070) | (0.228) | (0.003) | (0.016) *** | I(1) | |

| −3.187 | −3.147 | −5.182 | −5.092 | ||

| (0.035) ** | (0.121) | (0.004) ** | (0.001) *** | I(0) | |

| % | −6.054 | −5.992 | −8.204 | −7.776 | |

| (0.001) * | (0.000) * | (0.000) ** | (0.000) *** | I(0) | |

| −1.705 | −0.544 | −1.751 | −2.416 | ||

| (0.414) | (0.972) | (0.092) *** | (0.036) *** | I(1) | |

| −0.864 | −2.155 | −5.248 | −5.115 | ||

| (0.781) | (0.491) | (0.000) ** | (0.003) *** | I(1) | |

| Estimated F-Test Values | Critical Values Bound Test, Unrestricted Intercept and Trend | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10% | 5% | 1% | |||||||

| Model | K | N | F-Statistics | I(1) | I(0) | I(1) | I(0) | I(1) | I(0) |

| 9 | 24 | 10.55 * | 2.99 | 1.18 | 3.3 | 2.14 | 3.97 | 2.65 | |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 4.425 | 2.973 | 1.488 | 0.144 |

| −0.310 | 0.125 | −2.473 | 0.005 ** | |

| −6.885 | 3.475 | −1.981 | 0.053 ** | |

| −4.323 | 2.150 | −2.011 | 0.043 ** | |

| 2.069 | 0.868 | 2.384 | 0.038 * | |

| 3.706 | 2.033 | 1.822 | 0.098 * | |

| 0.751 | 0.416 | 1.807 | 0.101 * | |

| −0.180 | 0.483 | −0.373 | 0.717 | |

| (%) | −0.244 | 0.117 | −2.090 | 0.016 *** |

| 0.079 | 0.021 | 3.721 | 0.004 *** | |

| 0.107 | 0.219 | 0.489 | 0.635 | |

| −0.183 | 0.049 | −3.733 | 0.022 ** | |

| 0.278 | 0.136 | 2.042 | 0.080 *** | |

| R-squared | 0.997 | Adjusted R-squared | 0.994 | |

| S.E. of regression | 0.099 | Akaike info criterion | −1.478 | |

| Sum squared resid | 0.099 | Schwarz criterion | −0.836 | |

| F-statistic | 310.19 | Durbin–Watson stat | 2.187 | |

| Prob(F-statistic) | 0.0000 | |||

| Dignostic Tests | ||||

| χ2 Normal | 0.923 | χ2 ARACH | 0.190 | |

| χ2 RESET | 2.488 | χ2 SERIAL | 1.362 |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 2.491 | 0.378 | 6.587 | 0.050 ** |

| −6.885 | 3.475 | −1.981 | 0.053 ** | |

| −8.372 | 4.779 | −2.003 | 0.031 ** | |

| 1.710 | 0.681 | 2.511 | 0.051 ** | |

| 3.063 | 1.645 | 1.862 | 0.092 *** | |

| −0.621 | 0.332 | −1.870 | 0.091 *** | |

| −0.149 | 0.395 | −0.377 | 0.714 | |

| (%) | −0.244 | 0.117 | −2.090 | 0.009 * |

| 0.065 | 0.017 | 3.890 | 0.008 * | |

| 0.088 | 0.178 | 0.498 | 0.629 | |

| −0.168 | 0.041 | −4.097 | 0.024 ** | |

| 0.264 | 0.114 | 2.315 | 0.036 ** | |

| Error Correction Representation- Short Run Coefficients | ||||

| −6.885 | 6.475 | −1.063 | 0.313 | |

| −4.823 | 2.850 | −1.6911 | 0.093 ** | |

| 2.069 | 0.868 | 2.384 | 0.038 ** | |

| 3.706 | 2.033 | 1.822 | 0.098 *** | |

| −0.751 | 0.416 | −1.807 | 0.101 *** | |

| −0.180 | 0.483 | −0.373 | 0.717 | |

| (%) | −0.044 | 0.117 | −0.374 | 0.716 |

| 0.079 | 0.021 | 3.721 | 0.004 ** | |

| 0.107 | 0.219 | 0.489 | 0.635 | |

| −0.083 | 0.049 | −1.690 | 0.122 *** | |

| 0.278 | 0.136 | 2.044 | 0.008 * | |

| −1.210 | 0.135 | −8.945 | 0.000 * | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ganbaatar, B.; Huang, J.; Shuai, C.; Nawaz, A.; Ali, M. Empirical Analysis of Factors Affecting the Bilateral Trade between Mongolia and China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4051. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074051

Ganbaatar B, Huang J, Shuai C, Nawaz A, Ali M. Empirical Analysis of Factors Affecting the Bilateral Trade between Mongolia and China. Sustainability. 2021; 13(7):4051. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074051

Chicago/Turabian StyleGanbaatar, Bayarmaa, Juan Huang, Chuanmin Shuai, Asad Nawaz, and Madad Ali. 2021. "Empirical Analysis of Factors Affecting the Bilateral Trade between Mongolia and China" Sustainability 13, no. 7: 4051. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074051

APA StyleGanbaatar, B., Huang, J., Shuai, C., Nawaz, A., & Ali, M. (2021). Empirical Analysis of Factors Affecting the Bilateral Trade between Mongolia and China. Sustainability, 13(7), 4051. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074051