Improvement of Quality of Higher Education Institutions as a Basis for Improvement of Quality of Life

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How objective is the ranking conducted by the most crucial ranking lists of universities globally?

- Is accreditation sufficient to assess the quality of HEIs in the Republic of Serbia?

- What are the different methodologies and criteria for assessing the quality of HE?

2. Literature Review

- To what extent is the objective ranking of universities conducted by the most influential organisation?

- Is the process of accreditation sufficient for the evaluation of the quality of HEIs?

- Is there a specific methodology that could be used for the evaluation of the quality of the HEIs?

3. Materials and Methods

- The introduction of quality indicators in HE. This particular action has the following implementation steps (according to the Strategy and Action plan): (1) Definition of a set of indicators for monitoring of the condition of HE; (2) Improvement of accreditation standards; (3) Development of a model for the implementation of indicators (information system).

- Academic studies (bachelor and master)—Introduction of the ranking of study programs with implementation steps (1) Definition of a set of indicators; (2) Analysis of different ranking programs (based on the opinion of employers as well as based on knowledge of students); (3) Systematic inclusion of employers in the procedure of evaluation and ranking; (4) Establishment of a manual for ranking study programs.

4. Research Methodology and a Set of Indicators Definition

4.1. Research Methodology

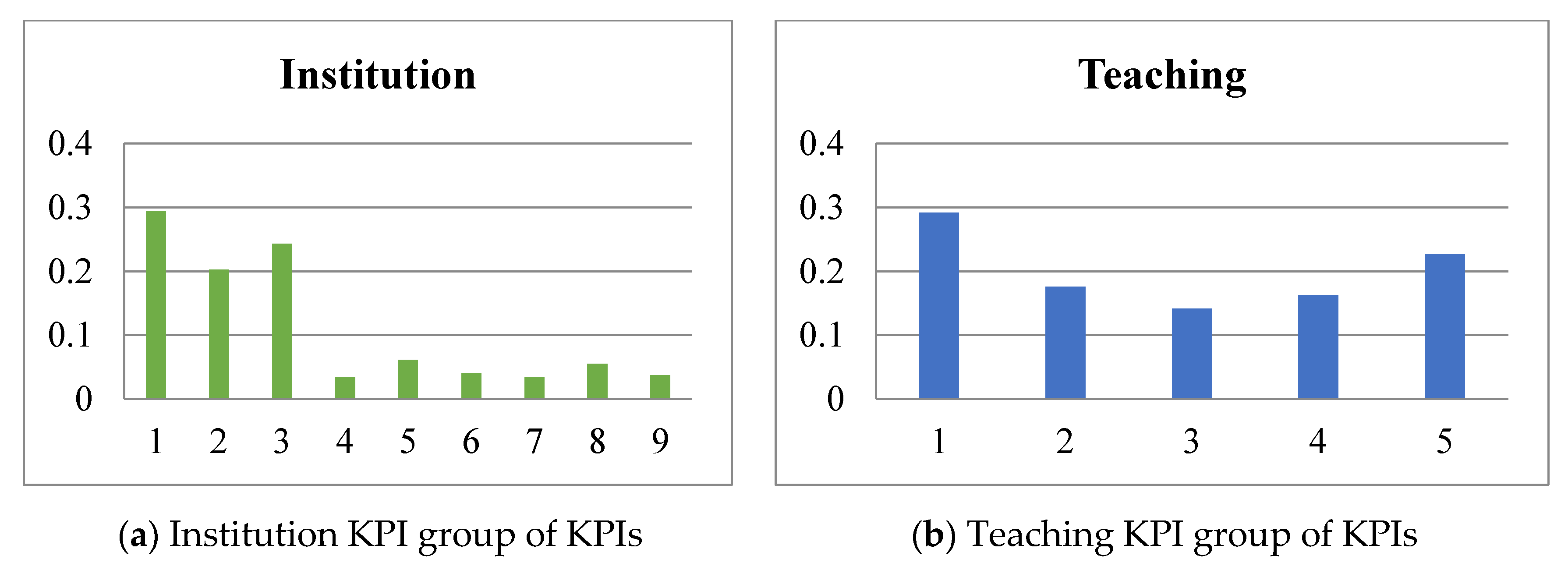

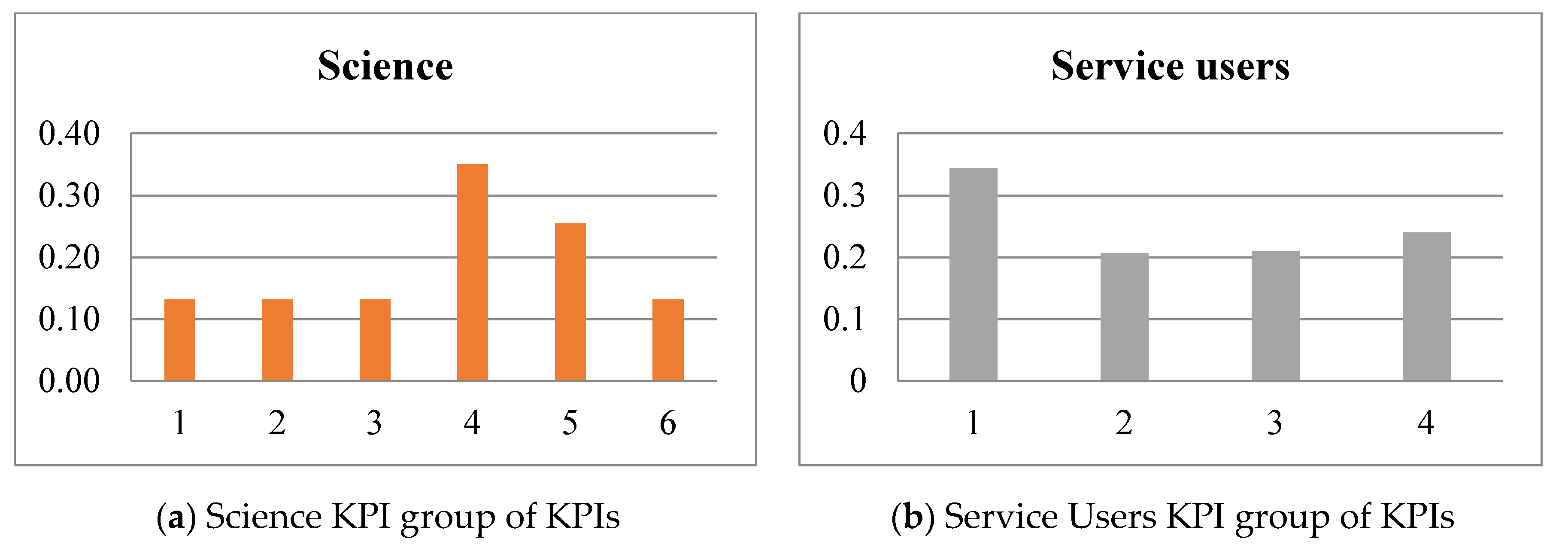

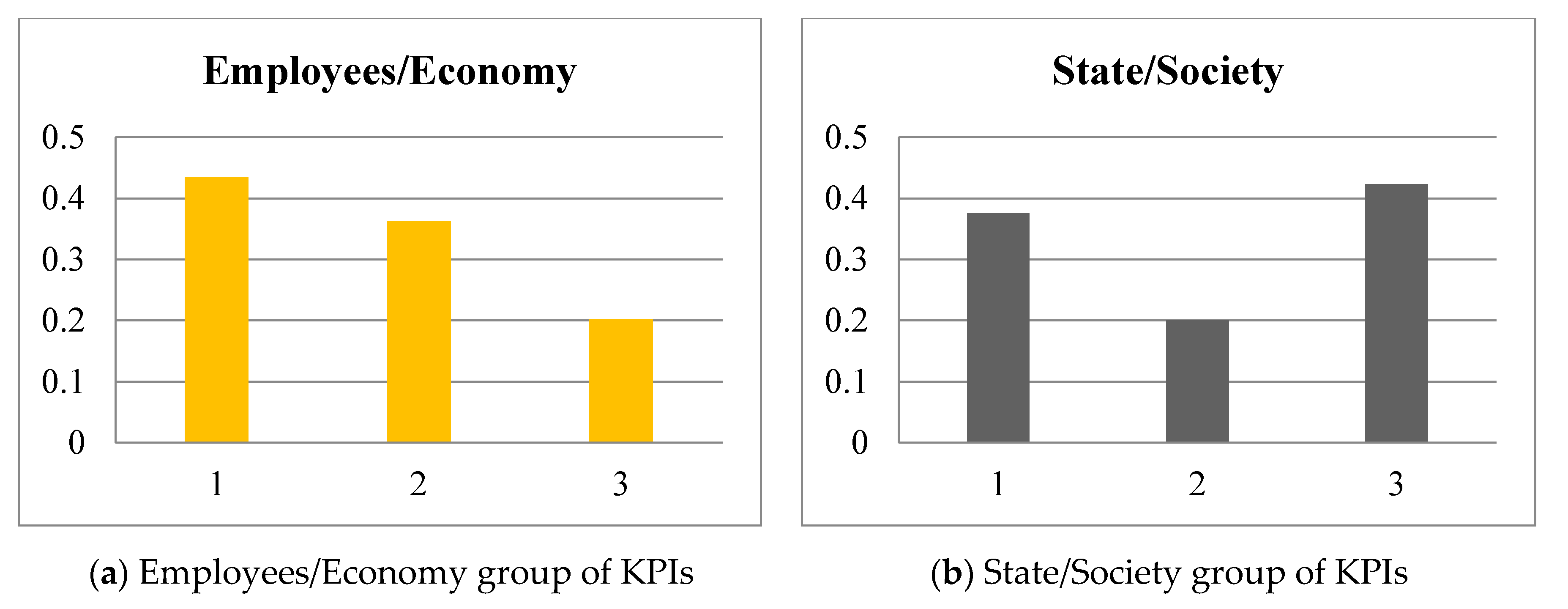

4.2. Set of Indicators Definition

5. Definition and Testing of the Mathematical Model for Ranking

Development of the Mathematical Model

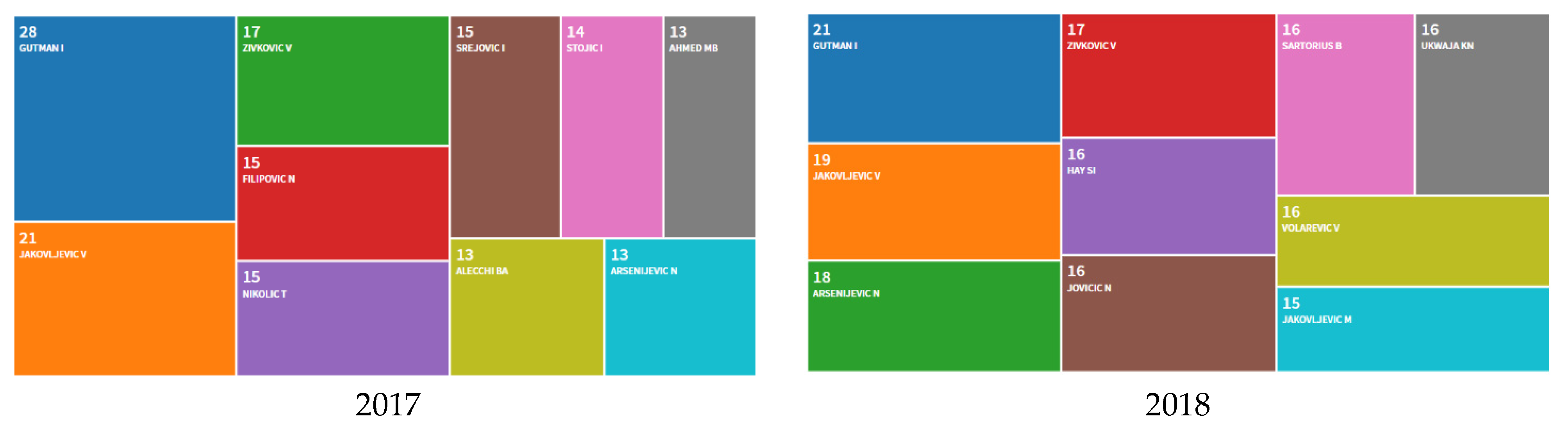

6. Scientometrics

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

8.1. Main Findings

- (1)

- The academic community and the universities in a specific country. Developing a system for measuring performance and multidimensional ranking of study programs and institutions should contribute to a better, higher quality, more efficient, market-oriented and socially responsible management of study programs and universities. Through KPIs, the ranking of study programs and institutions will enable focusing on critical processes, process benchmarking, comparison and thus improvement of key processes at universities in Serbia, which should contribute to higher levels of education, research, development and innovation processes, broader internationalisation as well as cooperation with industry both locally and across the region. On the other hand, all this affects the definition and redefines institutional strategies.

- (2)

- Students. According to the ranking of study programs and institutions, students will have opportunities to make choices that suit them best, bearing in mind the set of performance indicators which would indicate the essential parameters (for example, the number of unemployed graduates in a study program).

- (3)

- Industry and business. Business entities would have an overview of different orientations and parameters of defined study programs, market orientation and quality. In this way, it is possible to achieve feedback between HEIs and industry.

- (4)

- The National Employment Service and the Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia’s focus groups would benefit from the access to real data, their organised monitoring and better connections with HEIs and businesses. Today, for example, it is not possible to generate information on the number of unemployed graduates originated from individual institutions,

- (5)

- Government and state institutions (policymakers) can use the defined set of performance criteria to create the legal framework and recommendations for funding or financial models that should be incorporated as indicators for measuring the quality of the educational process.

8.2. Theoretical Implications

- (1)

- Defining models to support decision-making on quality objectives and business performance in HEIs;

- (2)

- Determining the measure of execution of processes, subprocesses and their KPIs based on the realised results in the form of performance for small and medium HEIs;

- (3)

- Determining and optimising specific KPIs based on the observed performance that needs to be improved and;

- (4)

- Predicting HEIs’ performance improvements based on established optimal KPI improvements.

8.3. Practical Implications

8.4. Study Limitations

8.5. Future Lines of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liefner, I. Funding, resource allocation, and performance in higher education systems. High. Educ. 2003, 46, 469–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Boer, H.; Jongbloed, B.; Benneworth, P.; Cremonini, L.; Kolster, R.; Kottmann, A.; Lemmens-Krug, K.; Vossensteyn, H. Performance-Based Funding and Performance Agreements in Fourteen Higher Education Systems; Center for Higher Education Policy Studies: Enschede, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ramasamy, N.; Rajesh, R.; Pugazhendhi, S.; Ganesh, K. Development of a hybrid BSC-AHP model for institutions in higher education. Int. J. Enterp. Netw. Manag. 2016, 7, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, L.; Li, J. Study on the quality of private university education based on analytic hierarchy process and fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method 1. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2016, 31, 2241–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari-Shirkouhi, S.; Mousakhani, S.; Tavakoli, M.; Dalvand, M.R.; Šaparauskas, J.; Antuchevičienė, J. Importance-performance analysis based balanced scorecard for performance evaluation in higher education institutions: An integrated fuzzy approach. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2020, 21, 647–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alach, Z. Performance measurement and accountability in higher education: The puzzle of qualification completions. Tert. Educ. Manag. 2016, 22, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, S.P. Transformational leadership practices in community school. Tribhuvan Univ. J. 2019, 33, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garde Sanchez, R.; Flórez-Parra, J.M.; López-Pérez, M.V.; López-Hernández, A.M. Corporate governance and disclosure of information on corporate social responsibility: An analysis of the top 200 universities in the shanghai ranking. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodall, T.; Hiller, A.; Resnick, S. Making sense of higher education: Students as consumers and the value of the university experience. Stud. High. Educ. 2014, 39, 48–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, M.G.; McAndrew, W.P. To each according to their ability? Academic ranking and salary inequality across public colleges and universities. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2018, 25, 34–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epifanić, V.; Urošević, S.; Dobrosavljević, A.; Kokeza, G.; Radivojević, N. Multi-criteria ranking of organisational factors affecting the learning quality outcomes in elementary education in Serbia. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2021, 22, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baporikar, N. Stakeholder approach for quality higher education. In Research Anthology on Preparing School Administrators to Lead Quality Education Programs; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 1664–1690. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, M.; Sauvageot, C. Constructing an Indicator System or Scorecard for Higher Education: A Practical Guide; UNESCO-International Institute for Educational Planning: Paris, France, 2011; ISBN 978-92-803-1329-1. [Google Scholar]

- Nurcahyo, R.; Wardhani, R.K.; Habiburrahman, M.; Kristiningrum, E.; Herbanu, E.A. Strategic formulation of a higher education institution using balance scorecard. In Proceedings of the 2018 4th International Conference on Science and Technology (ICST), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 7–8 August 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, M. Using indicators in higher education policy: Between accountability, monitoring and management. In Research Handbook on Quality, Performance and Accountability in Higher Education; Edward Elgar Publishing: Chatterham, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Rymarzak, M.; Marmot, A. Higher education estate data accountability: The contrasting experience of UK and Poland. High. Educ. Policy 2020, 33, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gontareva, I.; Borovyk, M.; Babenko, V.; Perevozova, I.; Mokhnenko, A. Identification of efficiency factors for control over information and communication provision of sustainable development in higher education institutions. Wseas Trans. Environ. Dev. 2019, 15, 593–604. [Google Scholar]

- Agasisti, T.; Munda, G.; Hippe, R. Measuring the efficiency of European education systems by combining Data Envelopment Analysis and Multiple-Criteria Evaluation. J. Product. Anal. 2019, 51, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, T.L. Higher education in the sustainable development goals framework. Eur. J. Educ. 2017, 52, 414–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunn, A. Metrics and methodologies for measuring teaching quality in higher education: Developing the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF). Educ. Rev. 2018, 70, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.; Marques, C.S.; Justino, E.; Mendes, L. Understanding social responsibility’s influence on service quality and student satisfaction in higher education. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256, 120597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kryscynski, D.; Coff, R.; Campbell, B. Charting a path between firm-specific incentives and human capital-based competitive advantage. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 42, 386–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, O.A.A. The Effect of Quality of Higher Education System on the Compatibility Between the Skills of Graduates and the Requirements of the Labour Market in Egypt. Ph.D. Thesis, Cardiff Metropolitan University, Cardiff, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Leal Filho, W.; Shiel, C.; Paço, A.; Mifsud, M.; Ávila, L.V.; Brandli, L.L.; Molthan-Hill, P.; Place, P.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Vargas, V.R.; et al. Sustainable Development Goals and sustainability teaching at universities: Falling behind or getting ahead of the pack? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S. Identifying indicators of university autonomy according to stakeholders’ interests. Tert. Educ. Manag. 2019, 25, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Cano, A.; Curiel-Marin, E.; Torralbo-Rodríguez, M.; Vallejo-Ruiz, M. Questioning the Shanghai Ranking methodology as a tool for the evaluation of universities: An integrative review. Scientometrics 2018, 116, 2069–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceško, M.; Nedeljković, J.; Živković, M.; Đurđić, S. Public and private higher education institutions in Serbia: Legal regulations, current status and opinion survey. Eur. J. Educ. 2020, 55, 514–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Peñalvo, F.J.; Corell, A.; Abella-García, V.; Grande-de-Prado, M. Recommendations for Mandatory Online Assessment in Higher Education During the COVID-19 Pandemic. In Radical Solutions for Education in a Crisis Context; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kayani, M. Analysis of Socio-Economic Benefits of Education in Developing Countries: A Example of Pakistan. Bull. Educ. Res. 2017, 39, 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Sam, V. Overeducation among Graduates in Developing Countries: What Impact on Economic Growth? University Library of Munich: München, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Duerrenberger, N.; Warning, S. Corruption and education in developing countries: The role of public vs. private funding of higher education. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2018, 62, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, M.H.; Gornitzka, А. (Eds.) Building the Knowledge Economy in Europe: New Constellations in European Research and Higher Education Governance; Edward Elgar Publishing: Chatterham, UK, 2014; ISBN 978 1 78254 528 6. [Google Scholar]

- Krüger, K.; Parellada, M.; Samoilovich, D.; Sursock, A. Governance reforms in European university systems. In The Case of Austria, Denmark, Finland, France, the Netherlands and Portugal; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Case, J.M.; Marshall, D.; Linder, C. Being a student again: A narrative study of a teacher’s experience. Teach. High. Educ. 2010, 15, 423–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, M.C.; Novaski, O.; Anholon, R. SERVQUAL model applied to higher education public administrative services. Braz. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2017, 14, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Aracil, A.; Palomares-Montero, D. Examining benchmark indicator systems for the evaluation of higher education institutions. High. Educ. 2010, 60, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B.A. Assessing Organisational Performance in Higher Education; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-0-7879-8640-7. [Google Scholar]

- Becket, N.; Brookes, M. Evaluating quality management in university departments. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2016, 14, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massy, W.F.; Sullivan, T.A.; Mackie, C. Improving measurement of productivity in higher education. Chang. Mag. High. Learn. 2013, 45, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, M.J.; Sarrico, C.S.; Amaral, A. Implementing Quality Management Systems in Higher Education Institutions. In Quality Assurance and Management; Savsa, M., Ed.; INTECH: Rijeka, Yugoslavia, 2012; pp. 129–146. [Google Scholar]

- Dick, G.P.; Tarí, J.J. A Review of Quality Management Research in Higher Education Institutions; Univesrity of Kent: Kent, UK, 2013; Kent Busines School Working Paper Series No 274. [Google Scholar]

- Altbach, P.G. Rankings Season Is Here. Econ. Political Wkly. 2010, 45, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Ramírez, G.; Berger, J.B. Rankings, accreditation, and the international quest for quality: Organising an approach to value in higher education. Qual. Assur. Educ. 2014, 22, 88–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cidral, W.A.; Oliveira, T.; Di Felice, M.; Aparicio, M. E-learning success determinants: Brazilian empirical study. Comput. Educ. 2018, 122, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Alias, N.; Othman, M.S.; Marin, V.I.; Tur, G. A model of factors affecting learning performance through the use of social media in Malaysian higher education. Comput. Educ. 2018, 121, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Márquez, B.L.; Escudero-Torres, M.A.; Hurtado-Torres, N.E. Being highly internationalised strengthens your reputation: An empirical investigation of top higher education institutions. High. Educ. 2013, 66, 619–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalmers, D. Defining Quality Indicators in the Context of Quality Models; The University of Western Australia: Crawley, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kanji, G.K.; Malek, A.; Tambi, B.A. Total quality management in UK higher education institutions. Total Qual. Manag. 1999, 10, 129–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findler, F.; Schönherr, N.; Lozano, R.; Stacherl, B. Assessing the impacts of higher education institutions on sustainable development—an analysis of tools and indicators. Sustainability 2019, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallio, K.M.; Kallio, T.J.; Grossi, G. Performance measurement in universities: Ambiguities in the use of quality versus quantity in performance indicators. Public Money Manag. 2017, 37, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, J. Improving Quality Management in Higher Education Institutions in Developing Countries through Strategic Planning. Asian J. Contemp. Educ. 2020, 4, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwain, A.A.A.; Lim, K.T.; Othman, S.N. TQM and academic performance in Iraqi HEIs: Associations and mediating effect of KM. Tqm J. 2017, 29, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biloshchytskyi, A.; Myronov, O.; Reznik, R.; Kuchansky, А.; Andrashko, Y.; Paliy, S.; Biloshchytska, S. A method to evaluate the scientific activity quality of HEIs based on a scientometric subjects presentation model. Вoстoчнo-Еврoпейский журнал передoвых технoлoгий 2017, 6, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Soewarno, N.; Tjahjadi, B. Mediating effect of strategy on competitive pressure, stakeholder pressure and strategic performance management (SPM): Evidence from HEIs in Indonesia. Benchmarking Int. J. 2020, 27, 1743–1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleacă, E.; Fleacă, B.; Maiduc, S. Aligning strategy with sustainable development goals (SDGs): Process scoping diagram for entrepreneurial higher education institutions (HEIs). Sustainability 2018, 10, 1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooli, C. Governing and managing higher education institutions: The quality audit contributions. Eval. Program Plan. 2019, 77, 101713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khashab, B.; Gulliver, S.R.; Ayoubi, R.M. A framework for customer relationship management strategy orientation support in higher education institutions. J. Strateg. Mark. 2020, 28, 246–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, N.; Hashim, R.A.; Valdez, N.P.; Yaacob, A. Managing diversity in higher education: A strategic communication approach. J. Asian Pac. Commun. 2018, 28, 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agasisti, T.; Johnes, G. Efficiency, costs, rankings and heterogeneity: The case of US higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 2015, 40, 60–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soh, K. What the Overall doesn’t tell about world university rankings: Examples from ARWU, QSWUR, and THEWUR in 2013. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2015, 37, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauhvargers, A. Global University Rankings and Their Impact; European University Association: Brussels, Belgium, 2011; p. 85. [Google Scholar]

- Daraio, C.; Bonaccorsi, A.; Simar, L. Rankings and university performance: A conditional multidimensional approach. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 244, 918–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazelkorn, E. Reshaping higher education. In Rankings and the Reshaping of Higher Education; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2015; pp. 203–227. [Google Scholar]

- Hazelkorn, E. Rankings and the Public Good Role of Higher Education. Int. High. Educ. 2019, 99, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, K. Control by numbers: New managerialism and ranking in higher education. Crit. Stud. Educ. 2015, 56, 190–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baty, P. The times higher education world university rankings, 2004–2012. Ethics Sci. Environ. Politics 2014, 13, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millot, B. International rankings: Universities vs. higher education systems. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2015, 40, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammarfelt, B. Beyond coverage: Toward a bibliometrics for the humanities. In Research Assessment in the Humanities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 115–131. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyke, N. Twenty years of university report cards. High. Educ. Eur. 2005, 30, 103–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kováts, G. “New” Rankings on the Scene: The U21 Ranking of National Higher Education Systems and U-Multirank. In The European Higher Education Area; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altbach, P. The dilemmas of ranking. Int. High. Educ. 2006, 42, 2–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marginson, S.; Van der Wende, M. To rank or to be ranked: The impact of global rankings in higher education. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 2007, 11, 306–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakır, M.P.; Acartürk, C.; Alaşehir, O.; Çilingir, C. A comparative analysis of global and national university ranking systems. Scientometrics 2015, 103, 813–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lužanin, Z. Quality Indicators. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Novi Sad, Novi Sad, Serbia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tasić, N. Model of Key Performance Indicators of Higher Education Institutions. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Novi Sad, Novi Sad, Republic of Serbia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Petrusic, I. Development of Methodology and Ranking Model of Higher Education Institutions in Croatia. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gačanović, I. The Question of World University Rankings, or: On the Challenges Facing Contemporary Higher Education Systems. Issues Ethnol. Anthropol. 2010, 5, 185–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauhvargers, A. Where are the global rankings leading us? An analysis of recent methodological changes and new developments. Eur. J. Educ. 2014, 49, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anowar, F.; Helal, M.A.; Afroj, S.; Sultana, S.; Sarker, F.; Mamun, K.A. A critical review on world university ranking in terms of top four ranking systems. In New Trends in Networking, Computing, E-learning, Systems Sciences, and Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 312, pp. 559–566. [Google Scholar]

- Moed, H.F. A critical comparative analysis of five world university rankings. Scientometrics 2017, 110, 967–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klochkov, Y. Monitoring centre for science and education. In Proceedings of the 2016 5th International Conference on Reliability, Infocom Technologies and Optimisation (ICRITO 2016), Trends and Future Directions, Noida, India, 7–9 September 2016; pp. 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernon, M.M.; Balas, E.A.; Momani, S. Are university rankings useful to improve research? A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.D. Performance-based resource allocation for higher education institutions in China. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2019, 65, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ranking Systems | Indicators | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of Education | Teaching and Learning | Quality of Faculties/Institutional Mechanisms in Institutions | Research | Knowledge Transfer | International Orientation/Internationalization | Regional Engagement | Productivity | |

| ARWU | x | x | x | x | ||||

| U-MULTIRANK | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| PERSPEKTYWY | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| MACEDONIA HEIS | x | x | x | |||||

| HEQAM | x | x | x | |||||

| LUZANIN [74] | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| TASIC [75] | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| PETRUSIC [76] | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Indicators | Ranking Systems | |

|---|---|---|

| ARWU | U-MULTIRANK | |

| Quality of education | Alumni of an institution winning Nobel Prizes and Fields Medals 10% | |

| Teaching and learning | -Percentage of graduates in necessary studies -Percentage of graduates in master studies -Graduate on time in elementary studies -Graduate on time in master studies | |

| Quality of faculties/Institutional mechanisms in institutions | The staff of an institution winning Nobel Prizes and Fields Medals 20% -Highly cited researchers in 21 broad subject categories 20% | |

| Research | -Papers published in Nature and Science* 20% -Papers indexed in Science Citation Index-expanded and Social Science Citation Index 20% | -Number of quotes -Total number of research publications -Relative number of research publications -Revenue from external research -Artistic performance -Number of citations in top publications -Interdisciplinary publications -Postdoctoral posts -Professional publications -Research partnership strategy -School graduates |

| Knowledge transfer | -Publications published in collaboration with industry -Income from private sources -Total number of patents published -Relative number of published patents -Published patents in collaboration with industry -Number of spin-off companies -Number of patent publications -Revenue from continuing vocational training | |

| International orientation/Internationalization | -Frequency of foreign language study programs -Frequency of foreign language master study programs -Mobility of students -Foreign citizens in professor status -Joint international publications -Number of international doctorates | |

| Regional engagement | -Number of undergraduate students enrolled in the region -Number of graduates of master studies employed in the region -Number of students on an internship in the region -Number of joint publications in the region -Revenue from regional sources -Research partnership strategy in the region | |

| Productivity | -Per capita academic performance of an institution 10% | |

| Indicators | Ranking Systems | |

|---|---|---|

| PERSPEKTYWY | MACEDONIA HEIS | |

| Quality of education | -Prestige -Academic reputation -International recognition | |

| Teaching and learning | -Teaching staff -Accreditation | -Percentage of students who have passed the state matriculation examination 5% -Average number of credit students who have passed the state high school diploma 5% -Percentage of international students 5% -Academic staff/student ratio 4% -Percentage of academic staff with the highest grade 8% -Percentage of academic staff with one year or more work experience abroad 6% -Percentage of students with scholarships from the Ministry of Education and Science 6% -Institutional income per student 2% -Library charges per student 1% -Cost of IT infrastructure and equipment per student 1% -Percentage of students who have graduated in full time 1% -Percentage of undergraduate students with three months or more spent abroad due to foreign study/practical experience following national agreements 2% -Employment rate after graduation 4% |

| Quality of faculties/Institutional mechanisms in institutions | -Study area—first and second degree -Parameter estimation -Academic staff with the highest qualifications -Right to obtain a PhD -Right to award a doctoral degree with facilitation -Number of master study programs | |

| Research | -External research funding -Development of faculty/teaching staff -Awarded academic titles -Publications -Quotation -FWCI (Field-Weighted Citation Impact) Index | -Total research revenue per academic staff 4% -Revenue from research by the Ministry of Education and Science by academic staff 6% -Papers published in peer-reviewed journals by academic staff 6% -Papers indexed by Web of Science by academic staff 10% -Books published by academic staff 4% -Number of doctorates approved per academic staff 6% |

| Knowledge transfer | -Reputation of employers -The economic situation of alumni | -Revenue from industry research by academic staff 6% -Patents by academic staff |

| International orientation/Internationalization | -Programs in foreign languages -Number of students studying in a foreign language -Number of foreign students -Foreign teachers -Exchange students (number of students leaving) -Exchange students (number of students to come) -Multicultural structure of the total number of students | |

| Regional engagement | ||

| Productivity | ||

| Ranking Systems | Indicators | |||

| Quality of Education | Teaching and Learning | Quality of Faculties/Institutional Mechanisms in Institutions | Research | |

| HEQAM | -Curricula -Teaching staff -The library | -Administrative services -E-service -Location -Infrastructure | ||

| Luzanin [74] | -International awards and scholarships | -Quality of newly enrolled students -Quality of students -Quality of graduates -The quality of the researchers -Quality of academic staff | -Study conditions -Research conditions | -Publications with a coauthor from abroad -Citation of researchers and publications -Interdisciplinary publications |

| Tasic [75] | -Average graduation time -Employment opportunity -The number of earnings of graduates -Multidisciplinarity of the study program -Delivery of teaching resources -Ability to use the internet -The size of the teaching group -Number of students who have completed doctoral studies -Questionnaires about the quality of teaching -Professional practice -Student research work -Organisation of teaching -Student exchange -Availability of information on the website | -Teachers with PhD -Accessibility of teaching staff | -Laboratories -Classrooms -Computer equipment -Student service | -Delivery of funds for science -Teacher awards and recognitions -Profit from science -Scientific works of teachers -Citation of teachers in scientific journals -Multidisciplinary research work |

| Petrusic [76] | -Quality of teaching and learning -Teacher/student relationship -Teachers | -Quality mechanisms of the teaching and research process | -Prestige (visibility) -Citation -Scientific productivity -Excellence in research -IF journal factor -Collaboration indicators -Number of scientific projects | |

| Ranking Systems | Indicators | |||

| Knowledge Transfer | International Orientation/Internationalization | Regional Engagement | Productivity | |

| HEQAM | -Career prospects -Connections of institutions with business -Improve technical skills -Improve communication skills -Language skills -Employment opportunities through daycare programs -Opportunities to continue to study abroad -Availability of exchange programs with other institutes. -Opportunity for graduate programs. | |||

| Luzanin [74] | -University–industrial research -Finishing works in cooperation with the economy -Student practice | -Academic staff with a doctorate at another domestic or foreign institution -Academic staff who have been engaged in teaching or scientific work abroad (for the last ten years) for at least three months | ||

| Tasic [75] | -Encouraging cooperation with the industry -Joint research projects with industry -Company training and courses -Work experience of teachers in the industry -Joint scientific papers with industry -Companies founded by the Faculty -Patents -Patents with industry -Profits from cooperation with the economy -Earnings from licenses sold -Citation of scientific papers in patents | -Possibility to study for foreign students -Joint study programs with foreign faculties -Networking with foreign faculties -The interest of international students to enrol in college -Profit from international research projects -International projects with foreign faculties -Visiting professors from abroad -Number of international students who have completed doctoral studies at the Faculty -Teachers’ scientific papers with colleagues from abroad -Employment in international companies | -Patents with regional companies -Courses and training for citizens -Summer schools for high school students -Final work of students in cooperation with regional companies -Open lectures for all people -Regional companies founded by the Faculty -The interest of high school students from the region to enrol in the Faculty -Earnings from regional companies -Professional practice in regional companies -Employment in regional companies -Scientific papers with regional companies -Research projects with the region | |

| Petrusic [76] | -Student mobility -Teacher mobility -Internationalisation | -Industry revenue -Transmission of research results to society -Career and relevance to the market | ||

| ID No. | Description | Calculation | Legend |

|---|---|---|---|

| Institution | |||

| ID 1 | An average grade from previous educational level | ; | x—an average of enrolled students five—maximum grade |

| ID 2 | Total number of students in the 1st year | ; | n—number of students |

| ID 3 | % of maximal 60 European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) from previous year | ; | x—number of students with 60 ECTS y—total number of students |

| ID 4 | Number of foreign students | ; | x—number of students y—number of foreign students |

| ID 5 | Percentage of graduates | ; | x—number of graduated students y—number of students enrolled in the first year |

| ID 6 | Finances of HEI (total income) | ; | x—total income y—number of employees |

| ID 7 | Financing of science | ; | x—financing for science y—total income |

| ID 8 | Income from students’ fees | ; | x—income from students y—total income |

| Teaching | |||

| TD1 | Number of study programs | ; | n—number of study programs |

| TD2 | Number of students in lecturing groups | ; | x—number of students in the group y—number of students at the study program |

| TD3 | Evaluation of study program (students evaluation) | ; | n—students satisfaction with the study program |

| TD4 | Evaluation of teaching process program (students evaluation) | ; | n—evaluation of teaching |

| TD5 | Student internship | ; | x—number of students with internship y—total number of students |

| Science | |||

| SD1 | Published manuscripts | ; | x—number of publications in the last year y—number of research staff |

| SD2 | Number of publication at SCI, SSCI | ; | x—number of publications at SCI y—total number of publications |

| SD3 | Number of books | ; | x—number of books during the year y—total number of teachers |

| SD4 | Academic staff mobility | ; | x—number of staff with mobility y—total number of staff |

| SD5 | Students’ mobility | ; | x—number of students at HEIs abroad y—total number of students |

| SD6 | Publications in international cooperation | ; | x—number of publications with international cooperation y—total number of publications |

| Stakeholders (students, parents) | |||

| SSD1 | The average duration of studies | ; | n—average years |

| SSD2 | Learning outcomes in graduate students | ; | x—number of students with eight average and higher y—total number of students |

| SSD3 | Unemployment rate of graduates | ; | x—number of graduate students employed during the first year after graduation y—number of students at year |

| SSD4 | Students’ scholarship (from industry) | ; | x—number of students with scholarship y—total number of students |

| Employers (business) | |||

| ED1 | Projects with business entities | ; | x—number of projects with business y—total number of projects |

| ED2 | Number of BSc and MSc realised with business | ; | x—number of BSc and MSc realised with business y—total number of BSc and MSc |

| ED3 | Scientific manuscripts with business | ; | x—number of manuscripts with business y—total number of manuscripts |

| Society/State | |||

| SS1 | Participation in national projects | ; | x—number of national projects y—total number of projects |

| SS2 | Number of projects financed by the state | ; | x—number of projects financed by the state y—total number of projects |

| SS3 | Public lectures | ; | n—number of public lectures |

| No of Group | Group/Dimension | No | Indicator | ID | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | Institution | 1 | An average grade from previous educational level | I1 | 0.826 |

| 2 | Total number of students in the 1st year | I2 | 303 | ||

| 3 | % of maximal 60 ECTS from previous year | I3 | 0.284 | ||

| 4 | Number of foreign students | I4 | 0.008 | ||

| 5 | Percentage of graduates | I5 | 0.766 | ||

| 6 | Condition of studies (students evaluation) | I6 | 4.33 | ||

| 7 | Finances of HEI (total income) | I7 | 2,549,185.710 | ||

| 8 | Financing of science | I8 | 0.2192 | ||

| 9 | Income from students’ fees | I9 | 227,847.222 | ||

| II | Teaching | 1 | Number of study programs | II1 | 10 |

| 2 | Number of students in lecturing groups | II2 | 0.75 | ||

| 3 | Evaluation of study program (students evaluation) | II3 | 4.27 | ||

| 4 | Evaluation of teaching process program (students evaluation) | II4 | 4.69 | ||

| 5 | Student internship | II5 | 1 | ||

| III | Science | 1 | Published manuscripts | III1 | 1.113 |

| 2 | Number of publication at SCI, SSCI | III2 | 0.125 | ||

| 3 | Number of books | III3 | 0.0435 | ||

| 4 | Academic staff mobility | III4 | 0.0174 | ||

| 5 | Students’ mobility | III5 | 0.0181 | ||

| 6 | Publications in international cooperation | III6 | 0.3047 | ||

| IV | Stakeholders (students, parents) | 1 | The average duration of studies | IV1 | 4.2 |

| 2 | Learning outcomes in graduate students | IV2 | 0.1803 | ||

| 3 | An unemployment rate of graduates | IV3 | 0.6544 | ||

| 4 | Students’ scholarship (from industry) | IV4 | 0.0083 | ||

| V | Employers (business entities) | 1 | Projects with business entities | V1 | 0.3509 |

| 2 | Number of BSc and MSc realised with business | V2 | 0.4264 | ||

| 3 | Scientific manuscripts with business | V3 | 0.0859 | ||

| VI | Society/State | 1 | Participation in national projects | VI1 | 0.2105 |

| 2 | Number of projects financed by the state | VI2 | 0.2105 | ||

| 3 | Public lectures | VI3 | 10 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lazić, Z.; Đorđević, A.; Gazizulina, A. Improvement of Quality of Higher Education Institutions as a Basis for Improvement of Quality of Life. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084149

Lazić Z, Đorđević A, Gazizulina A. Improvement of Quality of Higher Education Institutions as a Basis for Improvement of Quality of Life. Sustainability. 2021; 13(8):4149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084149

Chicago/Turabian StyleLazić, Zorica, Aleksandar Đorđević, and Albina Gazizulina. 2021. "Improvement of Quality of Higher Education Institutions as a Basis for Improvement of Quality of Life" Sustainability 13, no. 8: 4149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084149

APA StyleLazić, Z., Đorđević, A., & Gazizulina, A. (2021). Improvement of Quality of Higher Education Institutions as a Basis for Improvement of Quality of Life. Sustainability, 13(8), 4149. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084149