Analysis of Corporate Social Responsibility Execution Effects on Purchase Intention with the Moderating Role of Customer Awareness

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. CSR

2.2. Stakeholder View on CSR

2.3. Customer Responses to CSR

2.4. CSR in a Developing Economy

2.5. CSR in Pakistan

3. Conceptual Model and Hypotheses Development

3.1. The Relationship between CSR and Purchase Intention

3.2. The Relationship between CSR and Trust

3.3. The Relationship between CSR and Brand Image

3.4. The Relationship between Trust and Purchase Intention

3.5. The Relationship between Brand Image and Purchase Intention

3.6. Moderating Role of Awareness

4. Research Methodology

4.1. Instruments’ Development

4.2. Sample and Data Collection

5. Data Analysis and Results

5.1. Analysis Techniques and Common Method Bias

5.2. Measurement Model

5.3. Discriminant Validity

5.4. The Structural Model

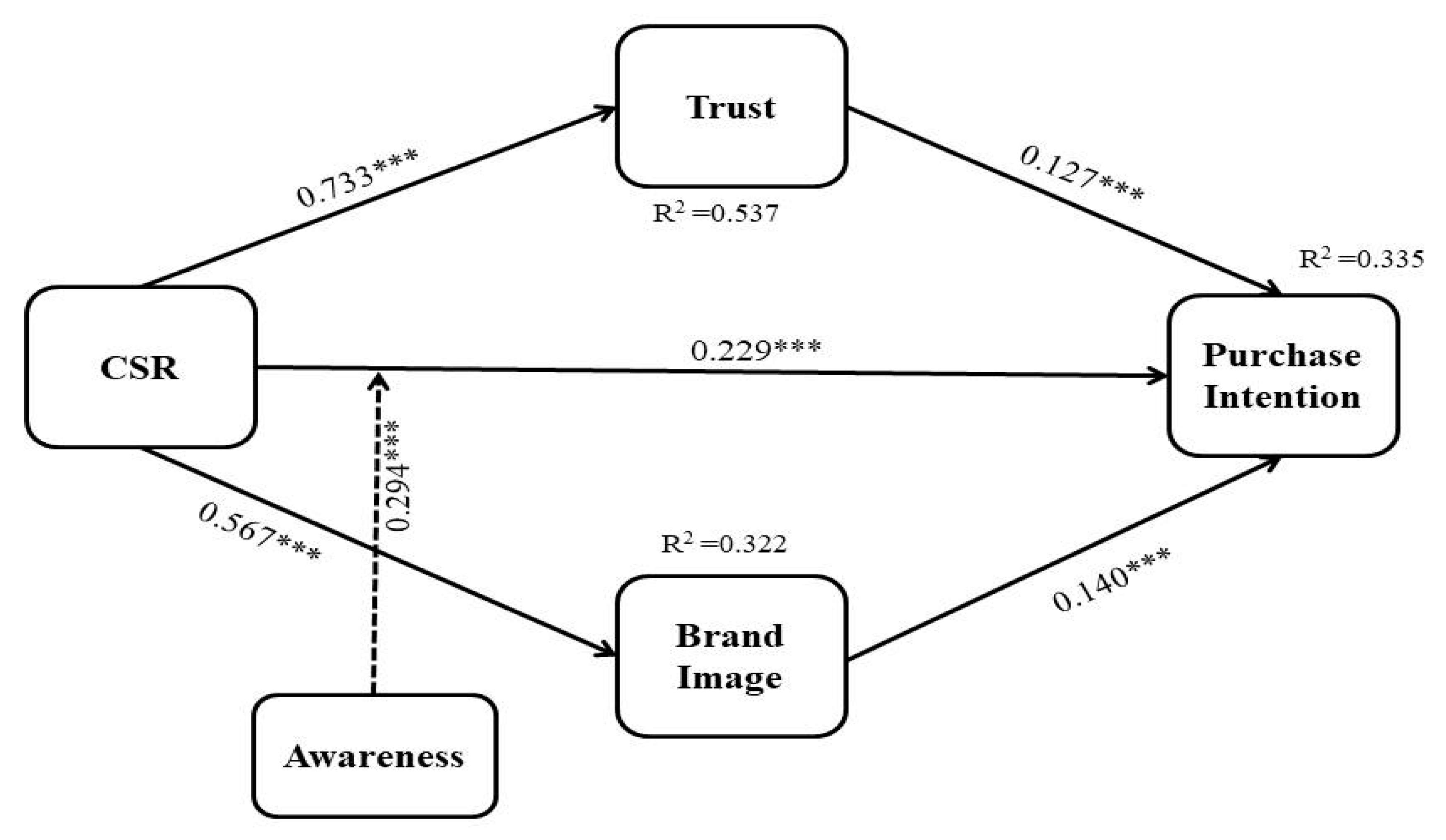

6. Discussion and Implications

7. Conclusions, Limitations, and Direction for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Antonio, M.S.; Nugraha, H.F. Peran intermediasi sosial perbankan syariah: Inisiasi pelayanan keuangan bagi masyarakat miskin. J. Keuang. Dan Perbank. 2012, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolvand, M.; Charsetad, P. Corporate social responsibility and brand equity in industrial marketing. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2013, 3, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Öberseder, M.; Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Gruber, V. “Why don’t consumers care about CSR?”: A qualitative study exploring the role of CSR in consumption decisions. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 104, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Y.; Liu, B.; Huan, T.-C.T. Renewal or not? Consumer response to a renewed corporate social responsibility strategy: Evidence from the coffee shop industry. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fang, S.; Huan, T.-C.T. Consumer response to discontinuation of corporate social responsibility activities of hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2017, 64, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaaland, T.I.; Heide, M.; Grønhaug, K. Corporate social responsibility: Investigating theory and research in the marketing context. Eur. J. Mark. 2008, 42, 927–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caruana, R.; Carrington, M.J.; Chatzidakis, A. “Beyond the attitude-behaviour gap: Novel perspectives in consumer ethics”: Introduction to the thematic symposium. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 215–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Olde, E.M.; Valentinov, V. The moral complexity of agriculture: A challenge for corporate social responsibility. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2019, 32, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Khojastehpour, M.; Jamali, D. Institutional complexity of host country and corporate social responsibility: Developing vs developed countries. Soc. Responsib. J. 2020, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berens, G.; Van Riel, C.B.; Van Bruggen, G.H. Corporate associations and consumer product responses: The moderating role of corporate brand dominance. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar, G.S.; Olkhovikov, K.M. University social responsibility: Notion and phenomena. In Proceedings of the Актуальные прoблемы сoциoлoгии культуры, oбразoвания, мoлoдежи и управления, Yekaterinburg, Russia, 10 November 2016; pp. 39–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk, R.; Kucharska, W. Corporate social responsibility practices incomes and outcomes: Stakeholders’ pressure, culture, employee commitment, corporate reputation, and brand performance. A Polish–German cross-country study. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 595–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A. The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Votaw, D. Genius becomes rare: A comment on the doctrine of social responsibility Pt. I. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1972, 15, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, A. Theorising corporate social responsibility as an essentially contested concept: Is a definition necessary? J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maignan, I.; Ferrell, O.C. Measuring corporate citizenship in two countries: The case of the United States and France. J. Bus. Ethics 2000, 23, 283–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Kang, J.; Low, B.S. Corporate social responsibility and stakeholder value maximization: Evidence from mergers. J. Financ. Econ. 2013, 110, 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.L.; Mattila, A.S. Improving consumer satisfaction in green hotels: The roles of perceived warmth, perceived competence, and CSR motive. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 42, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskentli, S.; Sen, S.; Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility: The role of CSR domains. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 95, 502–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Grønhaug, K. The impact of corporate social responsibility on consumer brand advocacy: The role of moral emotions, attitudes, and individual differences. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 95, 514–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Lee, H.; Kim, C. Corporate social responsibilities, consumer trust and corporate reputation: South Korean consumers’ perspectives. J. Bus. Res. 2014, 67, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-Y.; Lee, C.-K.; Kim, H. The influence of corporate social responsibility on travel company employees. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.B.; Ramus, C.A. Corporate social responsibility reputation effects on MBA job choice. SSRN Electron. J. 2003, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Russo, A.; Perrini, F. Investigating stakeholder theory and social capital: CSR in large firms and SMEs. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 91, 207–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, M.E. A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steurer, R.; Langer, M.E.; Konrad, A.; Martinuzzi, A. Corporations, stakeholders and sustainable development I: A theoretical exploration of business–society relations. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 61, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Harrison, J.S.; Wicks, A.C.; Parmar, B.L.; De Colle, S. Stakeholder Theory: The State of the Art; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, D.J.; Jones, R.E. Stakeholder mismatching: A theoretical problem in empirical research on corporate social performance. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 1995, 3, 229–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The four faces of corporate citizenship. Bus. Soc. Rev. 1998, 100, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghian, M.; D’Souza, C.; Polonsky, M. A stakeholder approach to corporate social responsibility, reputation and business performance. Soc. Responsib. J. 2015, 11, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freeman, R.E. The politics of stakeholder theory: Some future directions. Bus. Ethics Q. 1994, 4, 409–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.A.; Forster, W.R. CSR and stakeholder theory: A tale of Adam Smith. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, D. The future of corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2001, 9, 225–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, D.K.; Welford, R.J.; Hills, P.R. CSR and the environment: Business supply chain partnerships in Hong Kong and PRDR, China. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2009, 16, 250–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, O. Environmental, social and governance reporting in China. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2014, 23, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, L.; Ruiz, S.; Rubio, A. The role of identity salience in the effects of corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 84, 65–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Mirshak, R. Corporate social responsibility (CSR): Theory and practice in a developing country context. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 72, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turker, D. Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 411–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’riordan, L.; Fairbrass, J. Corporate social responsibility (CSR): Models and theories in stakeholder dialogue. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 83, 745–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Korschun, D.; Sen, S. Strengthening stakeholder–company relationships through mutually beneficial corporate social responsibility initiatives. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 257–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Consumer–company identification: A framework for understanding consumers’ relationships with companies. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Doing better at doing good: When, why, and how consumers respond to corporate social initiatives. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2004, 47, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, P.M.; Vasquez-Parraga, A.Z. Consumer social responses to CSR initiatives versus corporate abilities. J. Consum. Mark. 2013, 30, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peloza, J.; Shang, J. How can corporate social responsibility activities create value for stakeholders? A systematic review. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2011, 39, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Sen, S. Maximizing business returns to corporate social responsibility (CSR): The role of CSR communication. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Act: Communication from the Commission to the European...—Google Scholar. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Communication+from+the+Commission+to+the+European+Parliament,+the+Council,+the+Economic+and+Social+Committee+and+the+Committee+of+the+Regions.+A+Renewed+EU+Strategy+2011%E2%80%9314+for+Corporate+Social+Responsibility&author=European+Commission&publication_year=2011 (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Fernández-Guadaño, J.; Sarria-Pedroza, J.H. Impact of corporate social responsibility on value creation from a stakeholder perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rowley, T.; Berman, S. A brand new brand of corporate social performance. Bus. Soc. 2000, 39, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Lee, S. Effects of different dimensions of corporate social responsibility on corporate financial performance in tourism-related industries. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 790–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomvilailuk, R.; Butcher, K. The effect of CSR knowledge on customer liking, across cultures. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2013, 31, 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handelman, J.M.; Arnold, S.J. The role of marketing actions with a social dimension: Appeals to the institutional environment. J. Mark. 1999, 63, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Europe, C.S.R. MORI 2000: The First Ever European Survey of Consumers’ Attitudes towards Corporate Social Responsibility (Kurzfassung). Available online: http://www.csreurope.org/aboutus.CSRfactsandfigures_page397.aspx (accessed on 15 December 2020).

- Lee, C.-Y. Does corporate social responsibility influence customer loyalty in the Taiwan insurance sector? The role of corporate image and customer satisfaction. J. Promot. Manag. 2019, 25, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigors, M.; Rockenbach, B. Consumer Social Responsibility. Manag. Sci. 2016, 62, 3123–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manasakis, C. Business ethics and corporate social responsibility. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2018, 39, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visser, W. Corporate social responsibility in developing countries. In The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Simionescu, L.N. The relationship between corporate social responsibility (csr) and sustainable development (sd). Intern. Audit. Risk Manag. 2015, 38, 179–190. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, W.; Frynas, J.G.; Mahmood, Z. Determinants of corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosure in developed and developing countries: A literature review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Karam, C. Corporate social responsibility in developing countries as an emerging field of study. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 32–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mian, S.N. Corporate social disclosure in Pakistan: A Case Study of Fertilizers Industry. J. Commer. 2010, 2, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Waheed, A. Evaluation of the State of Corporate Social Responsibility in Pakistan and a Strategy for Implementation. A Report written for Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan and United Nations Development Program. 2005. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.468.7745&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 13 March 2021).

- Makki, M.A.M.; Lodhi, S.A. Determinants of corporate philanthropy in Pakistan. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. (PJCSS) 2008, 1, 17–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ehsan, S.; Nazir, M.S.; Nurunnabi, M.; Raza Khan, Q.; Tahir, S.; Ahmed, I. A Multimethod approach to assess and measure corporate social responsibility disclosure and practices in a developing economy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R. Perceived corporate social responsibility’s impact on the well-being and supportive green behaviors of hotel employees: The mediating role of the employee-corporate relationship. Tour. Manag. 2019, 72, 437–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supanti, D.; Butcher, K. Is corporate social responsibility (CSR) participation the pathway to foster meaningful work and helping behavior for millennials? Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 77, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, M.-K.; Yi, Y.; Bagozzi, R.P. Effects of customer participation in corporate social responsibility (CSR) programs on the CSR-brand fit and brand loyalty. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2016, 57, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J. Impact of total quality management on corporate green performance through the mediating role of corporate social responsibility. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaderi, Z.; Mirzapour, M.; Henderson, J.C.; Richardson, S. Corporate social responsibility and hotel performance: A view from Tehran, Iran. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 29, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.J.; Kang, K.H. Implementing corporate social responsibility strategies in the hospitality and tourism firms: A culture-based approach. Tour. Econ. 2019, 25, 520–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B.; Shabana, K.M. The business case for corporate social responsibility: A review of concepts, research and practice. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdeen, A.; Rajah, E.; Gaur, S.S. Consumers’ beliefs about firm’s CSR initiatives and their purchase behaviour. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2016, 34, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoroso, D.L.; Roman, F. Corporate social responsibility and purchase intention: The roles of loyalty, advocacy and quality of life in the Philippines. Int. J. Manag. 2015, 4, 25–41. [Google Scholar]

- Mulaessa, N.; Wang, H. The effect of corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities on consumers purchase intention in China: Mediating role of consumer support for responsible business. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2017, 9, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hosmer, L.T. Strategic planning as if ethics mattered. Strateg. Manag. J. 1994, 15, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatma, M.; Rahman, Z.; Khan, I. Building company reputation and brand equity through CSR: The mediating role of trust. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2015, 33, 840–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, M.L.; Anholon, R.; Cooper Ordoñez, R.E.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; Santa-Eulalia, L.A.; Leal Filho, W. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) practices developed by Brazilian companies: An exploratory study. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2018, 25, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. The process model of corporate social responsibility (CSR) communication: CSR communication and its relationship with consumers’ CSR knowledge, trust, and corporate reputation perception. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 154, 1143–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elg, U.; Hultman, J. CSR: Retailer activities vs consumer buying decisions. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2016, 44, 640–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Branding perspectives on social marketing. Acr N. Am. Adv. 1998, 25, 299–302. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.S.; Choe, J.Y.J.; Petrick, J.F. The effect of celebrity on brand awareness, perceived quality, brand image, brand loyalty, and destination attachment to a literary festival. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, N.R.N.A.; Rahman, N.I.A.; Khalid, S.A. Environmental corporate social responsibility (ECSR) as a strategic marketing initiatives. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 130, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arco-Castro, L.; López-Pérez, M.V.; Pérez-López, M.C.; Rodríguez-Ariza, L. How market value relates to corporate philanthropy and its assurance. The moderating effect of the business sector. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2020, 29, 266–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lion, A.; Macchion, L.; Danese, P.; Vinelli, A. Sustainability approaches within the fashion industry: The supplier perspective. Supply Chain Forum Int. J. 2016, 17, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden, D.; Harwood, I.A.; Woodward, D.G. The effects of procurement policies on ‘downstream’corporate social responsibility activity: Content-analytic insights into the views and actions of SME owner-managers. Int. Small Bus. J. 2011, 29, 259–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.-I.; Wang, W.-H. Impact of CSR perception on brand image, brand attitude and buying willingness: A study of a global café. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2014, 6, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, A.; Francis, A.; Kyire, L.A.; Mohammed, H. The effect of corporate social responsibility on brand building. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2014, 6, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, M.T.; Wong, I.A.; Shi, G.; Chu, R.; Brock, J.L. The impact of corporate social responsibility (CSR) performance and perceived brand quality on customer-based brand preference. J. Serv. Mark. 2014, 28, 181–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Pérez, A.; Del Bosque, I.R. CSR influence on hotel brand image and loyalty. Acad. Rev. Latinoam. De Adm. 2014, 27, 267–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricks, J.M. An assessment of strategic corporate philanthropy on perceptions of brand equity variables. J. Consum. Mark. 2005, 22, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, K.; Saha, R.; Goswami, S.; Dahiya, R. Consumer’s response to CSR activities: Mediating role of brand image and brand attitude. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.; Rashid, B. A conceptual model of corporate social responsibility dimensions, brand image, and customer satisfaction in Malaysian hotel industry. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2018, 39, 358–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coles, T.; Fenclova, E.; Dinan, C. Tourism and corporate social responsibility: A critical review and research agenda. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2013, 6, 122–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hassan, M.; Iqbal, Z.; Khanum, B. The role of trust and social presence in social commerce purchase intention. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. (PJCSS) 2018, 12, 111–135. [Google Scholar]

- Khudiyev, M.; Szabó, Z. Consumer behavior in sports marketing in the context of football. Studia Mundi–Econ. 2020, 7, 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, C.Y.; Baker, J.A.; Wagner, J. The effects of appropriateness of service contact personnel dress on customer expectations of service quality and purchase intention: The moderating influences of involvement and gender. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 1164–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, M.M.; Parvez, N. Impact of service quality, trust, and customer satisfaction on customers loyalty. Abac J. 2009, 29, 24–38. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.-Z.; Hsu, T.-H. Designing a model of FANP in brand image decision-making. Appl. Soft Comput. 2011, 11, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L.; Lehmann, D.R. Brands and branding: Research findings and future priorities. Mark. Sci. 2006, 25, 740–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, M.; Liu, F.; Lee, J.; Soutar, G. The influence of negative publicity on brand equity: Attribution, image, attitude and purchase intention. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2018, 27, 440–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cretu, A.E.; Brodie, R.J. The influence of brand image and company reputation where manufacturers market to small firms: A customer value perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2007, 36, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, B.; Donthu, N.; Lee, S. An examination of selected marketing mix elements and brand equity. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2000, 28, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Hyun, Y.J. A model to investigate the influence of marketing-mix efforts and corporate image on brand equity in the IT software sector. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2011, 40, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-H.; Shin, D. Consumers’ responses to CSR activities: The linkage between increased awareness and purchase intention. Public Relat. Rev. 2010, 36, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tian, Z.; Wang, R.; Yang, W. Consumer responses to corporate social responsibility (CSR) in China. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 101, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigley, S. Gauging consumers’ responses to CSR activities: Does increased awareness make cents? Public Relat. Rev. 2008, 34, 306–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, M.J.; Neville, B.A.; Whitwell, G.J. Why ethical consumers don’t walk their talk: Towards a framework for understanding the gap between the ethical purchase intentions and actual buying behaviour of ethically minded consumers. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Luo, Y.; Wang, S.L. Moral degradation, business ethics, and corporate social responsibility in a transitional economy. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 120, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B.; Korschun, D. The role of corporate social responsibility in strengthening multiple stakeholder relationships: A field experiment. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 158–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeurissen, R. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; JSTOR: Capstone, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Servaes, H.; Tamayo, A. The impact of corporate social responsibility on firm value: The role of customer awareness. Manag. Sci. 2013, 59, 1045–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pomering, A.; Dolnicar, S. Assessing the prerequisite of successful CSR implementation: Are consumers aware of CSR initiatives? J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 85, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, A.; Zhang, Q.; Rashid, Y.; Zaman Khan, S. The impact of corporate social responsibility on buying tendencies from the perspective of stakeholder theory and practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 1307–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.; Del Bosque, I.R. CSR and customer loyalty: The roles of trust, customer identification with the company and satisfaction. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 35, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, E.; Bruno, J.M.; Sarabia-Sanchez, F.J. The impact of perceived CSR on corporate reputation and purchase intention. Eur. J. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2019, 28, 206–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fatma, M.; Rahman, Z. The CSR’s influence on customer responses in Indian banking sector. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 29, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.K.-K. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) techniques using SmartPLS. Mark. Bull. 2013, 24, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, M.; Agarwal, R. Through a glass darkly: Information technology design, identity verification, and knowledge contribution in online communities. Inf. Syst. Res. 2007, 18, 42–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Bookstein, F.L. Two structural equation models: LISREL and PLS applied to consumer exit-voice theory. J. Mark. Res. 1982, 19, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henseler, J.; Sarstedt, M. Goodness-of-Fit Indices for Partial Least Squares Path Modeling. Comput. Stat. 2013, 28, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Chin, W.W.; Marcolin, B.L.; Newsted, P.R. A partial least squares latent variable modeling approach for measuring interaction effects: Results from a Monte Carlo simulation study and an electronic-mail emotion/adoption study. Inf. Syst. Res. 2003, 14, 189–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 546–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Yi, Y. On the evaluation of structural equation models. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1988, 16, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Matthews, L.M.; Matthews, R.L.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated guidelines on which method to use. Int. J. Multivar. Data Anal. 2017, 1, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Data Analysis Multivariate; Pearson Education: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial least squares structural equation modeling. Handb. Mark. Res. 2017, 26, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rönkkö, M.; Evermann, J. A critical examination of common beliefs about partial least squares path modeling. Organ. Res. Methods 2013, 16, 425–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Bae, J. Cross-cultural differences in concrete and abstract corporate social responsibility (CSR) campaigns: Perceived message clarity and perceived CSR as mediators. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2016, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Popoli, P. Linking CSR strategy and brand image: Different approaches in local and global markets. Mark. Theory 2011, 11, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongpitch, S.; Minakan, N.; Powpaka, S.; Laohavichien, T. Effect of corporate social responsibility motives on purchase intention model: An extension. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 37, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Polonsky, M.J.; Polonsky, M.J.; Scott, D. An empirical examination of the stakeholder strategy matrix. Eur. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 1199–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, A.; Zhang, Q. Effect of CSR and ethical practices on sustainable competitive performance: A case of emerging markets from stakeholder theory perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Cao, M.; Zhang, F.; Liu, J.; Li, X. Effects of corporate social responsibility on customer satisfaction and organizational attractiveness: A signaling perspective. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2020, 29, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J. The effects of corporate social responsibility and price on consumer responses. J. Consum. Aff. 2005, 39, 121–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Item | Source |

|---|---|---|

| CSR | The company tries to sponsor pro-environmental programs. The company tries to protect the environment. The company tries to carry out programs to reduce pollution by controlling emissions. The company has established ethical guidelines for business activities. The company tries to become an ethically trustworthy company. The company provides a wide range of indirect benefits to improve the quality of their employees’ lives. The company emphasizes the importance of their social responsibilities to society. The company contributes to campaigns and projects that promote the well-being of society. | [115] |

| Trust | The services of the company make me feel a sense of security. I trust the quality of the company. Hiring services of this company guarantees quality assurance. This company is interested in its customers. This company is honest with its customers. | [116] |

| Brand Image | Using the company’s products is a good thing to do. Using the company’s products is valuable for me. The company offers a high level of service. | [117] |

| Awareness | Are you aware of any initiatives the company is involved in that are aimed at improving the social conditions in the community? Are you aware of any initiatives the company is involved in that are aimed at improving the environmental condition? | [118] |

| Purchase Intention | I shall continue considering the company as my main brand. I would keep being a customer of the company. I would recommend the company if someone asked my advice. | [117] |

| Respondents | Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 610 | 60.8% |

| Female | 392 | 39.12% | |

| Age | 18 to 30 years old | 391 | 39.02% |

| 31 to 40 years old | 265 | 26.44% | |

| 41 to 50 years old | 230 | 22.95% | |

| 51 years old and above | 116 | 11.57% | |

| Education | Primary Education or Lower | 70 | 6.98% |

| Middle School Education | 145 | 14.47% | |

| High School Education | 235 | 23.45% | |

| Bachelor Degree | 215 | 21.45% | |

| Diploma/Certificate | 135 | 13.47% | |

| Postgraduate Degree | 202 | 20.15% | |

| Profession | Students | 545 | 54.39% |

| Self Employed | 157 | 15.66% | |

| Job Holders | 135 | 13.47% | |

| Businessmen | 165 | 16.46% | |

| Income | 0–15,000 Rs. | 570 | 54.39% |

| 15,001–30,000 Rs. | 181 | 18.06% | |

| 30,001–50,000 Rs. | 151 | 15.06% | |

| 50,001–80,000 Rs. | 55 | 5.48% | |

| 80,001–100,000 Rs. | 28 | 2.79% | |

| More than 100,000 Rs. | 17 | 1.69% |

| Items | VIF |

|---|---|

| Awr1 | 1.310 |

| Awr2 | 1.310 |

| Brd1 | 1.517 |

| Brd2 | 1.510 |

| Brd3 | 1.569 |

| CSR * Awareness | 1.000 |

| CSR2 | 2.352 |

| CSR3 | 1.650 |

| CSR4 | 2.548 |

| CSR5 | 1.790 |

| CSR6 | 1.724 |

| CSR7 | 1.818 |

| CSR8 | 1.895 |

| PI1 | 1.942 |

| PI2 | 2.204 |

| PI3 | 1.831 |

| Tr1 | 1.769 |

| Tr2 | 1.919 |

| Tr3 | 1.632 |

| Tr4 | 1.643 |

| Tr5 | 1.235 |

| Loadings | CA | rho_A | CR | AVE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness | Awr1 | 0.840 | 0.713 | 0.710 | 0.852 | 0.742 |

| Awr2 | 0.882 | |||||

| Brand Image | Brd1 | 0.801 | 0.759 | 0.762 | 0.861 | 0.674 |

| Brd2 | 0.827 | |||||

| Brd3 | 0.834 | |||||

| CSR | Csr1 | 0.811 | 0.851 | 0.862 | 0.885 | 0.524 |

| Csr2 | 0.780 | |||||

| Csr3 | 0.662 | |||||

| Csr4 | 0.793 | |||||

| Csr5 | 0.720 | |||||

| Csr6 | 0.691 | |||||

| Csr7 | 0.683 | |||||

| Csr8 | 0.729 | |||||

| Purchase Intentions | PI1 | 0.864 | 0.837 | 0.836 | 0.902 | 0.754 |

| PI2 | 0.885 | |||||

| PI3 | 0.855 | |||||

| Trust | Tr1 | 0.798 | 0.807 | 0.814 | 0.867 | 0.569 |

| Tr2 | 0.814 | |||||

| Tr3 | 0.757 | |||||

| Tr4 | 0.776 | |||||

| Tr5 | 0.609 | |||||

| Awareness | Brand Image | CSR | Moderating Effect | Purchase Intentions | Trust | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness | 0.862 | |||||

| Brand Image | 0.172 | 0.821 | ||||

| CSR | 0.216 | 0.567 | 0.724 | |||

| Moderating Effect | −0.010 | 0.063 | −0.071 | 0.0851 | ||

| Purchase Intentions | 0.394 | 0.400 | 0.466 | −0.025 | 0.868 | |

| Trust | 0.202 | 0.634 | 0.733 | 0.011 | 0.443 | 0.754 |

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p-Values | Confidence Intervals | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.5% | 97.5% | ||||||

| CSR → Purchase Intentions | 0.229 | 0.231 | 0.054 | 4.255 *** | 0.000 | 0.127 | 0.336 |

| CSR → Trust | 0.733 | 0.736 | 0.016 | 45.007 *** | 0.000 | 0.699 | 0.766 |

| CSR → Brand Image | 0.567 | 0.570 | 0.029 | 19.783 *** | 0.000 | 0.514 | 0.622 |

| Trust → Purchase Intention | 0.127 | 0.125 | 0.059 | 2.159 *** | 0.031 | 0.007 | 0.235 |

| Brand Image → Purchase Intention | 0.140 | 0.139 | 0.050 | 2.775 *** | 0.006 | 0.042 | 0.236 |

| Awareness → Purchase Intention | −0.016 | −0.017 | 0.033 | 0.472 | 0.637 | −0.079 | 0.045 |

| CSR*Awareness → Purchase Intention | 0.294 | 0.294 | 0.037 | 8.033 *** | 0.000 | 0.226 | 0.363 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Q.; Ahmad, S. Analysis of Corporate Social Responsibility Execution Effects on Purchase Intention with the Moderating Role of Customer Awareness. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4548. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084548

Zhang Q, Ahmad S. Analysis of Corporate Social Responsibility Execution Effects on Purchase Intention with the Moderating Role of Customer Awareness. Sustainability. 2021; 13(8):4548. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084548

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Qingyu, and Sohail Ahmad. 2021. "Analysis of Corporate Social Responsibility Execution Effects on Purchase Intention with the Moderating Role of Customer Awareness" Sustainability 13, no. 8: 4548. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13084548