1. Introduction

The research focuses on rural areas, which, according to the Eurostat definition [

1], refer to all areas outside urban clusters (areas with at least 5000 inhabitant and at least 300 per km

2). Based on this definition, rural areas cover 75% of the European Union’s land area and are—obviously—the backbone of Europe’s primary sector [

2]. However, they tend to face a number of significant challenges, such as low access to markets, lack of infrastructure, a limited range of services, limited job opportunities and labour supply, and a higher risk of poverty and social exclusion [

3]. In order to overcome such challenges and boost their economies, rural areas are turning to collaborations between businesses, as well as between businesses and other important institutions (e.g., public authorities, research centres, universities, etc.), which is one of the most efficient tools for rural sustainable growth [

4].

The most relevant types of collaboration for the demands of rural areas are business clusters. Clusters, which have gained increasing prominence in economic development in the last couple of decades, can be viewed as geographical concentrations of interconnected firms and institutions in a certain field and can act as a way for regions to identify and develop their existing regional competitive advantage [

5,

6]. To a large degree, rural clusters arose from the need to address common rural challenges, such as insufficient access to basic services and infrastructure and long distances between actors [

7].

The main aim of this paper is to demonstrate that clusters can support the sustainable development of rural areas through the creation of shared value. Specifically, it is aimed at (a) understanding the patterns of created shared value among clusters in rural areas and (b) exploring how clusters contribute to generate an economic and societal impact in rural areas.

2. Literature Review

Shared value is a concept which first appeared in a 2006 article by Michael Porter and Mark Kramer [

8], elaborated in a 2011 piece [

9], and further defined and clarified in several articles and writings by both authors ever since, which discuss the creation of shared value. Essentially, creating shared value (CSV) refers to “policies and operating practices that enhance the competitiveness of a company while simultaneously advancing the economic and social conditions in the communities in which it operates” [

9]. As defined by the Shared Value Initiative, founded by Porter and Kramer, “shared value is a management strategy in which companies find business opportunities in social problems” [

10].

In short, based on the above, shared value combines a business’s success with increased financial and social capital for the community in which the said business is based. The concept of social capital was developed to reflect the added dimension of trust, relationships, and contact networks between people [

11]. Social capital complements “traditional” resources such as financial capital with the extra resources provided by social networks, trust, norms, and values, producing better outcomes [

12]. In other words, social capital provides a value-added contribution to other types of capital, or functions as a multiplier of their own effect [

13]. It should also be noted that, together with social benefits and as a part of the benefits to society, shared value also comes with clear environmental benefits for the community and promotes sustainable development [

14].

Exactly the same definitions of shared value can also be applied to clusters, which are, as explained, concentrations of businesses [

5]. However, the connection between clusters and shared value is deeper. Enabling cluster development was suggested by Porter and Kramer as one of the three ways in which businesses could create shared value [

8]. More recently, Kramer and Pfizer [

15] have introduced the concept of “shared value ecosystem”, which is even more strongly applicable to the concept of clusters. In short, while research on the exact relationship between CSV and clusters is still in its infancy, current definitions as well as evidence lead to the conclusion that, with their focus on an interrelation between businesses and close connection to the local communities, clusters represent a particularly fitting application of the shared value concept [

16]. In this way, whatever applies to individual businesses can be applied even more emphatically to clusters.

According to Porter and Kramer’s optimistic view, based on observing the launching of shared value initiatives by a number of companies known for their hard-nosed business approach, the concept of shared value—which focuses on the connections between societal and economic progress—has the power to unleash the next wave of global growth and to redefine capitalism [

9]. This perspective has, of course, received criticism [

17]. For example, Beschorner [

18] argues that the concept is too normatively thin and too economically narrow to reconnect businesses with society, explaining that the reinvention of capitalism requires companies to develop moral capabilities and specific skills in order to be “fit” for and contribute to new societal contexts [

18].

Despite the criticism, the concept of shared value has gained considerable ground in the years since the term was coined, and it has become an established strategy. Companies have embraced it, building and rebuilding business models around social good, which sets them apart from the competition and augments their success [

10]. The application and social impact of shared value is assisted by the quadruple helix concept [

19], as the involvement of NGOs, governments, and other stakeholders, offers businesses the power of scale to create real change on major social problems. The realisation that rural businesses and local communities can provide mutual benefits to each other can create a virtuous cycle of increasing value for both [

17].

Understanding shared value requires understanding the earlier concept of corporate social responsibility (CSR), against which CSV was defined in the original paper [

8]. CSR can be generally defined as a form of ethical self-regulation of businesses [

20]. In essence, CSV arose from the limitations of CSR as a novel way to look at the relationship between business and society, which treats corporate success and social welfare as mutually beneficial instead of as a zero-sum game. In their 2011 paper on the topic, Porter and Kramer note that while CSR initiatives “focus mostly on reputation and have only a limited connection to the business, CSV is integral to the company’s profitability and competitive position” [

9] (p. 6). For example, in terms of sustainability, while CSR might mean repairing environmental damage to improve a company’s public profile, CSV has the integral goal of sustainable development.

Creating value and capturing returns from that value are fundamental functions of business and the main reasons for the existence of collaborative relationships [

21]. As Porter and Kramer [

8,

9] note, no company is self-contained. Industrial organisations are naturally related to each other. They are dependent on each other’s production, distribution, and use of goods and services [

22]. Every company’s success depends on the supporting companies and infrastructure around it. Again, the concept of clusters and their success can be taken as proof of this conclusion.

Clusters carry even greater potential for the application of shared value. The areas where opportunities for the creation of shared value will be greatest are any potential gaps and deficiencies of clusters that can be addressed by further collaboration [

9]. Initiatives addressing cluster weaknesses that constrain companies will be much more effective than community-focused CSR programs, which often have limited impact because they target too many areas and do not often take value into account. Clusters are crucial in this because efforts to enhance infrastructure and institutions in a region often require collective action. As such, companies should try to enlist partners to share the cost, gain support, and assemble the right skills. The most successful cluster initiatives are those involving not only the private sector but other actors as well, such as trade associations, government agencies, and NGOs. A greater involvement means greater value shared among everyone involved [

9].

The present paper applies a qualitative and explorative approach to understanding the ways in which clusters could contribute to creating shared value in rural areas. This is done via the close examination of six different cases of such clusters across Europe, performed in

Section 4. The cases, as well as the methodology used to examine them, are outlined below. The paper is organised as follows.

Section 2 describes the research materials and methods used in the study.

Section 3 and

Section 4 present the main results and discussion of the study, respectively. Finally,

Section 5 provides the summary and conclusion of the study with remarks for policy features and future research.

3. Materials and Methods

We identified six different clusters across the EU based on the criteria of connection to rural areas; clusters within agro-food, bioenergy and bio-based industry; and clusters that included actors representing rural businesses, knowledge providers, supply chain partners, and public bodies. In addition, it was a criterion that the effect of the clusters’ work would have an impact on the rural community. Primary and secondary data were used for this study. The primary data came from interviewing cluster managers and cluster participants and from workshops in the EC-funded Horizon2020 “RUBIZMO” (N_773621) project. The secondary data were collected from desktop research including reports, statistical data bases, websites, and research on the clusters. The data included:(a) general information on the clusters (location, fields, members, main activities, and how it was founded), (b) how the cluster produces shared value by a strategy or actions, and (c) the cluster’s vision for future actions, plans, expansion, especially in terms of shared value creation. The aim of the data collection was to establish grounds for understanding the ways in which the cluster contributed to the creation of shared value with regard to business opportunities (economic aspect) and improved living conditions in rural areas (societal and environmental impact).

Due to their explorative nature, the case studies only indicated patterns for creating shared value and could not be used for comparisons and benchmarking or, for drawing general conclusions about clusters and shared value. However, the case studies did explore how clusters contributed to generating an economic and societal impact in rural areas. The features of the cases, the ways in which these clusters created shared value for their communities, and the types of quantitative data which could be found to support this assertion were too varied to allow for comparisons between the cases. This can be considered as a shortcoming. However, addressing this shortcoming in an efficient way would have meant finding a way to benchmark the concept of shared value or to create a taxonomic measure for the development of clusters. Such measures did not seem to exist and developing them from scratch would have been extremely ambitious and way beyond the scope of current literature on the topic. While the creation of shared value has been defined in detail in the literature, as mentioned in the introduction, the existing definitions are descriptive in nature. Actually measuring the concept in practice is not a straightforward task.

In order to provide practical examples of how rural clusters and/or networks can create shared value for their surrounding communities, six different case studies are presented in the present paper. Each case is complemented by some general information of the cluster or network, before examining how it creates shared value according to the model put forward by Porter and Kramer and outlined in the introduction above [

8]. The examination of the cases allows some overall conclusions to be drawn about how rural clusters and/or networks create shared value in practice. All the cases examined play an integral part in the sustainable development of their local areas.

The present paper is a qualitative review of case studies, although the main focus is on specific numerical statistical figures in order to avoid subjective conclusions. The six different cases, taken from six different European countries, were selected according to the availability of information and data that are related to the impact of shared value as it is defined in the original model [

9]. The descriptive and statistical information provided in the results section was obtained directly from the records of the clusters/networks themselves, provided in confidential emails from cluster boards or members and belonging to the consortium of the EC-funded H2020 project RUBIZMO. As a result, data collection was mostly limited to the research work conducted within the RUBIZMO project and cannot be attributed to specific sources (e.g., literature references). Where this information was obtained from other sources, such as statistical databases or publications, these sources are clearly referenced in the text.

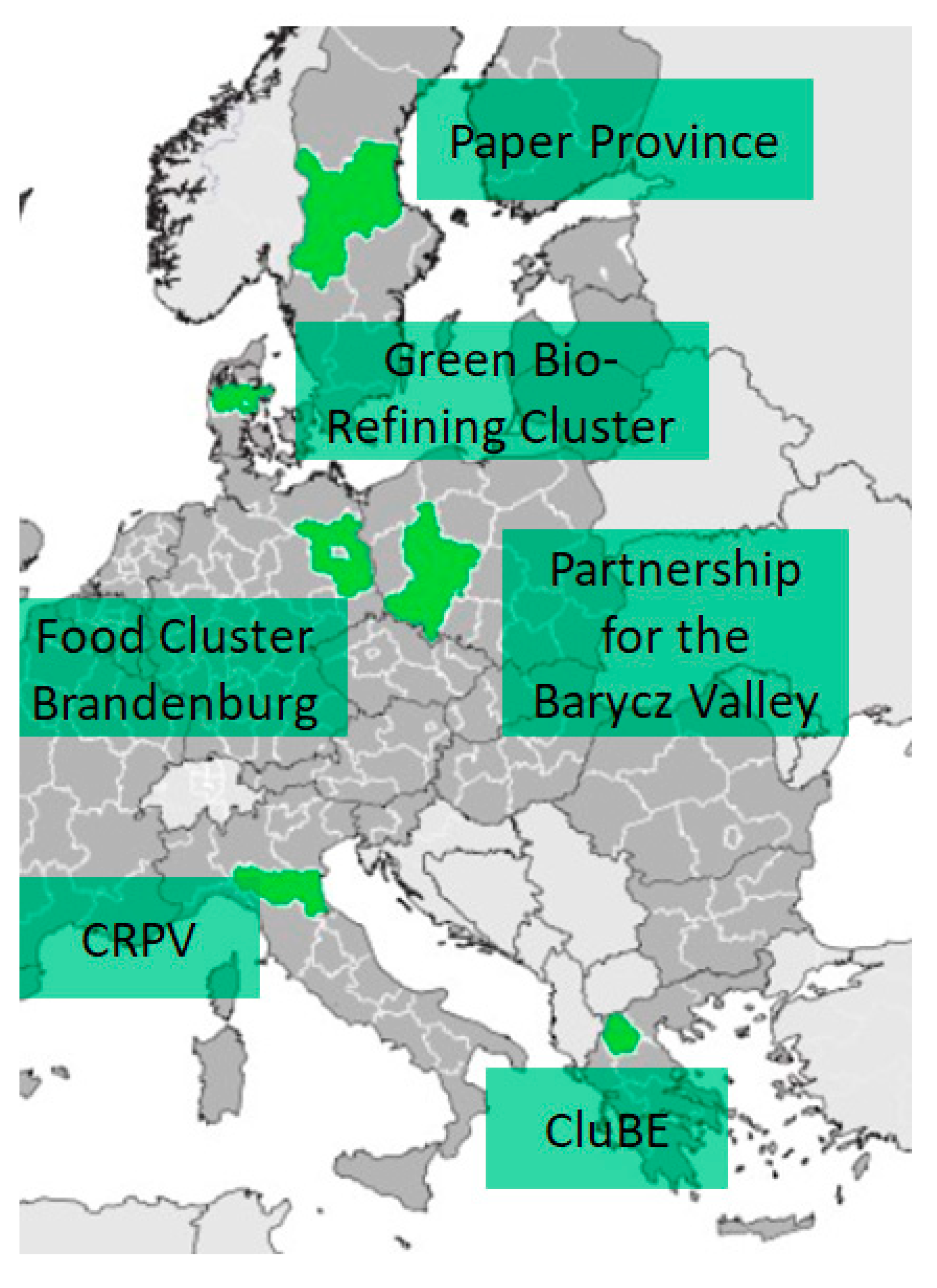

Each set of authors obtained information for one cluster located in their own region and with which they have ongoing contact in the framework of the RUBIZMO project. The information from all clusters was discussed between all authors (who are also researchers on the project) and a short selection of information for inclusion within the present paper was jointly made for each cluster. The six cases, described in detail in the following section and shown on the map in

Figure 1, are the following:

Cluster of Bioeconomy and Environment of Western Macedonia (CluBE), Greece

Food Cluster Brandenburg, Germany

Green Bio-refining Cluster, Denmark

Crop Production Research Centre (CRPV), Italy

Paper Province, Sweden

Association “Partnership for the Barycz Valley”, Poland

It should also be noted that, despite the qualitative nature of the study, a conscious effort was made to obtain quantitative data which demonstrated the clusters’ creation of shared value for the local areas via their economic and/or social impacts. This was sometimes challenging to accomplish. Still, a preference was shown towards quantitative information about the cases, with qualitative information used where it was deemed extremely relevant and interesting, and where a particular impact was, in practice, impossible to quantify.

4. Results

4.1. Cluster of Bioeconomy and Environment of Western Macedonia (CluBE), Greece

CluBE is a non-profit company established in 2014 among local actors and stakeholders of the Region of Western Macedonia in Greece and appears as a cluster. It was created by the initiative of a local champion, based on European expertise of clusters, but it was eventually supported by regional authorities. Its members include regional and local authorities, universities, and research institutes, as well as various enterprises. CluBE is pursuing R&D and business activities in the fields of bioeconomy (originally bioenergy) and environment in order to reinforce the green economy in the region and with the broader aim of decarbonisation in Western Macedonia.

CluBE is creating shared value for the local community through its activities. From 2015 to the end of 2019, 11 EC-funded projects were awarded to the cluster and its members in the area of Kozani, including the Municipality of Kozani it self, as well as some of its members, such as the Regional Development Agency of Western Macedonia, the local branch of the Centre for Research and Technology Hellas, and the companies Alfa Wood, DETEPA, DEYAK, AZ Bioenergia, Matesion, DIADYMA, etc.

The total budget for these projects during this time was EUR 4,915,065 (EUR 1,496,129 or 30.44% for CluBE itself and EUR 3,418,935 or 69.56% for its members). Based on staff costs and average person-month rates, this created 27.78 work positions for qualified people based on full-time equivalent (FTE) positions. Since all of these projects were approved based—largely—on their innovativeness, there is also a considerable gain in technological know-how for the beneficiaries, which is difficult to quantify but extremely important for the transfer of knowledge from and mainly to the region of Western Macedonia and its stakeholders.

It is also worth mentioning that CluBE was established during the economic crisis in Greece and thus has worked as an alternative to the overarching “business as usual” model. Although there are some good examples of cooperative spirit in Western Macedonia, the prevailing business approach has been one of individualism. In the framework of CluBE, the personal connections and relations developed among local stakeholders allowed a cooperative spirit to flourish, bringing hope to desperate regional actors.

Finally, CluBE initiated a procedure to improve the devastated environment of Western Macedonia: The shift from fossil fuels to bioenergy and other renewable forms of energy is expected to significantly reduce the CO2 released in the atmosphere. Additionally, its campaign to better and more actively manage the forest and agricultural residues is expected to play a major role in decreasing the wildfires in forests as well as the fires set by farmers to their fields, and therefore minimising the relevant emissions but also the risks to human life and infrastructure deterioration.

In addition, CluBE could play a significant role in the energy transition and post-lignite era of the region. The knowledge transfer from EU funded projects towards key stakeholders of the region together with the enhancement of the collaboration spirit between entrepreneurship and R&D will play a significant role and will be two of the developmental pillars towards a just and fair regional transition.

4.2. Food Cluster Brandenburg, Germany

The Food Cluster of Brandenburg was established to enable collaboration between companies in a region in which the food sector is key. Members include small- and medium-sized enterprises as well as large national and international companies in fields that involve the production and processing of food as well as its delivery to consumers. Member companies are active in agriculture, the food and beverage industry, logistics, and trade. One of its main activities is creating networks between research organizations, in particular for small- and medium-sized enterprises.

The Food Cluster has been creating shared value for the region in various ways. Overall, it is a major employer in the region, has boosted the regional economy, and positively impacted on regional R&D and know-how. Specific data are listed below.

Since its establishment in the year 2008 and until 2017, the turnover of the enterprises in the cluster has increased by 23.5%, which is above the average of other enterprises and even clusters in Brandenburg. A comparison of the cluster with the rest of the economy shows that the turnover per employee is more than 10% higher in the cluster economy.

In terms of turnover and employment subject to social insurance contributions, the food industry cluster is the largest of the four Brandenburg specific clusters. In the fiscal year 2016, the companies of the overall cluster accounted for 10.5% of the total turnover of all companies in Brandenburg. In 2018, with over 57,000 employees, it was one of the most employment-intensive clusters. The number of employees in 2017 was 50,714.

There is an increasing tendency to initiate R&D projects involving several companies, which can be interpreted as evidence of a growing awareness of the cluster’s common value. Currently, one in four projects initiated by companies in the cluster is the result of intensive cooperation between the member companies.

The number of newly initiated projects increased from 9 in 2017 to 22 in 2018. This represents an increase of almost 145%. While funding of around EUR 11 million was acquired for players in the region in 2017, this figure will rise to just under EUR 53 million in 2018—an increase of more than 380%.

One in ten farms in the region, including those belonging to or connected to cluster members, operates under strict ecological guidelines, making the region Germany’s leader in environmental farming.

The cluster is having an increasing impact on strategic orientation of enterprises in the food and bioeconomy sector, the cooperation between stakeholders in the sector, and the creation of steering structures and proper processes.

4.3. Green Bio-Refining Cluster, Denmark

The Green Bio-Refining Cluster came about due to a strategy announced by the regional government of Central Denmark for developing into a leading region for bio-refining, with particular emphasis on green biomass. The overall aim of the cluster is valorisation of green biomass, particularly grass, which grows well in Denmark. The cluster is new, and there is no formal organisation yet. Aarhus University together with the local incubator Agrobusiness Park established the interdisciplinary Centre for Circular Bioeconomy (CBIO). Activities come from different involved stakeholders as projects, conferences, and contracted production. So far, a demonstration program was funded with the aim of establishing networks and initiating innovation projects.

The cluster dynamics are rooted in projects about developing and commercializing new value chains centred around the production and processing of organic clover grass [

23]. The projects are funded by the regional government or the Danish government though innovation grants and private co-financing. The outcomes to date have demonstrated that it is possible to process grass into a feed concentrate that works in praxis; that grass protein concentrate matches the nutritional value of presently used feed protein sources; and that if a proper and feasible value chain can be established there would be new opportunities for farmers and businesses for generating an income from growing and processing grass. It has been demonstrated that the organic feed protein seems to be competitive to the price of imported soybean cakes [

24].

The projects have increased practical knowledge about the growing and processing of the biomass, logistics, how to use the protein paste as feed, and the feasibility of the value chain. Another important outcome of the projects has been to identify and connect those actors that would need to collaborate for realising green bio-refining activities. Research about the development of the green bio-refining cluster has shown that value chain actors share a common goal of realising value chains for production and marketing of grass protein and that actors are willing to engage in this new value chain [

24]. The projects have provided much detailed knowledge and practical experiences about how the new grass-protein value chain should be organised, and stakeholders with commercial interests have identified new business opportunities.

Solving the challenges of developing green bio-refining required collaboration and knowledge sharing across stakeholder groups. For example, a company producing equipment for harvesting grass developed a new harvesting machine to improve the grass yield, and this machine is now in the market. A compound feed producer tested the protein paste in existing compound feed and is interested in buying more of the paste on commercial terms. Furthermore, a survey [

25] carried out among farmers revealed that there is genuine interest in growing more organic clover grass for bio-refining and that producers of organic pigs and poultry are willing to use the protein paste in the feed. The potential market demand for feeding organic pigs in Denmark with grass protein was calculated to beca. 12,000 tons of protein. This would require 10,000–13,000 hectares of clover grass fields [

24]. Because grass is a good strategy for preventing nitrogen leaching, policies on water protection could stimulate a new business model for grassland owners.

The case study of the green bio-refining cluster in Central Denmark demonstrates that there is a motivation in diverse stakeholder groups for working towards developing the green bio-refining venture. The shared values that could be gained from producing grass protein exist at three different levels: economic, social, and environmental.

Economic benefits for the local community include improved income opportunities for farmers and businesses; patented bio-refining technologies that could be scaled up; new machines and feed products available in the market; and improved self-sufficiency with organic feed protein. Social benefits include new jobs created in rural areas; sustaining organic farms; provision of organic pork, poultry meat, and eggs to satisfy consumer demands in Denmark and selected export markets; and collaboration across stakeholder groups with a common goal. Finally, environmental benefits include: reducing environmental impact because grass prevents N-leaching into the water; eliminating transportation of imported soybean concentrates; keeping local production in line with the principles of organic agriculture; and sustaining of biodiversity.

4.4. Crop Production Research Centre (CRPV), Italy

CRPV is a cooperative located in Cesena (Northern Italy), operating in the development of research on crop production, including fruit, vegetables, cereals, seeds, and bioenergy. It is essentially functioning as an agricultural cluster, and it is focused on sustainable crop protection, genetic improvements, production optimisation, application of ICT (Information and Communication Technologies), bioenergy production, supporting farmers’ development, and dissemination of research results and technology transfer. The CRPV members are producers’ associations, institutes for technical assistance and professional education, provincial administrations, and the main economic organisations. The technical and scientific results of the research are expressed through annual and multi-annual programmes involving associative, cooperative, and consortium bodies and companies and other bodies whose institutional aims include the planning and enhancement of plant production sectors.

CRPV transforms the needs of market players into research projects involving universities, other research institutions, farms, and associations of farmers. The direct involvement of farms in projects and the dissemination of research data reduce the sense of alienation and detachment between researchers and technicians/farmers and make the farmer an informed subject, and therefore more aware and responsible for the effect of his actions.

In order for farmers to be able to respond to market needs, the CRPV has always carried out a genetic improvement activity by constituting new plant varieties in collaboration with national and world institutions. Through the projects coordinated by the CRPV, the research activity also focuses on aspects related to plant pathology and defence, insect monitoring and weather protection systems, irrigation, and economic aspects of farm management. In addition to the design and coordination of projects, CRPV is currently engaged in the construction of a “data supply chain” that allows the elaboration of big data from the agri-food chains in order to create and improve new tools and services in the agricultural field, aimed at technicians and farmers but also at consumers.

It participates in regional and European projects (H2020 and LIFE+). In 2018, about 240 operational units (such as public and private research institutes, consultants, and members of the CRPV as cooperative agricultural companies) were involved in the 70 projects managed by the CRPV. It publishes the results of research and experimentation in sector magazines, organizes conferences and training courses, and constantly updates internal databases, which are also linked to external databases.

To date, most of the projects carried out were financed by public funds. One of the main objectives of the CRPV is to increase funding from third-party entities that market and process plant products and to increase funding from other stakeholders. Over recent years, CRPV has aimed to spread the concept of agriculture as a protector of the public good, and hence their objective of stimulating international thematic networks and multi-actors that could facilitate the transfer of good practices from more developed realities, with the aim of spreading as much as possible the cultivation of agriculture and its role as protector of the public good.

4.5. Paper Province, Sweden

The decline of the paper and pulp industries in the region of Värmland, followed by severe structural challenges in Värmland during the 1990s, motivated Karlstad Municipality and other regional actors, both public and private, to join forces and establish the “Paper Province” cluster organisation. The Paper Province was later reorganised into an economic association, which today has more than 100 member companies [

26]. Among its members are now various world leaders in packaging material and packaging solutions, specialty paper, cardboard, paper and pulp and tissue machines, coating machines, and barriers (e.g., Stora Enso, Valmet Paper, SOMAS, and BTG). There are also a large number of SMEs, which provide the sector’s largest share of employment and turnover and provide key competencies [

26,

27]. The vision of the Paper Province is to be a leading competence node for a forest-based bioeconomy by using natural feedstock as an industrial processing input and expending minimum amounts of energy and waste, as all materials discarded by a process should be utilized as inputs for another process. An important part of the strategy is to create a large-scale demonstration project in which Paper Province—from a service perspective—can verify, test, and support development of new business models, services, and products derived from the forest-based industries value chain. The long-term aim is to create a transition from an industrial community to an innovative society [

28].

The European Cluster Observatory recognised Paper Province as one of seven “Top European Clusters in High Innovation Regions”, the only one in Sweden, after auditing2110 clusters in Europe. The cluster coordinates and develops collaborations between actors within the paper and pulp industry in the region. The competence is unique [

27]. The proximity to the raw material, modern infrastructure, and the central location in Northern Europe has made the cluster into a world leading area in the pulp and paper industry [

27]. The yearly turnover was higher than SEK 17 billion in 2010, and the export was worth SEK13.5 billion [

27]. The members of the cluster have invested SEK 1 billion yearly in the region since 1999. The Paper Province collaborates with a variety of partners to retain and enhance the competitiveness of the pulp and paper industry. In addition to the member companies, this cluster includes universities and a variety of public actors, such as municipalities, “Region Värmland”, VINNOVA, and the Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth (Tillväxtverket).

Since its founding in 1999 and its reorganization as an economic association in 2003, the Paper Province has created shared value for the region in various ways. Initially, the cluster activities were concentrated primarily on marketing the pulp and paper industry and on providing competence in addressing the need to improve the supply of qualified workforce in the area. Many initiatives were ventured for attracting students to various programmes and for developing capacity-building solutions according to company specifications, often in close cooperation with Karlstad University and Karlstad Municipality.

In 2004, the Paper Province started The Packaging Greenhouse AB20—an industrial research and development company engaged with base paper for packaging. The reason behind these activities is to create a meeting place, to enhance cooperation between the pulp and paper cluster and the University of Karlstad, and to attract new companies to the region. This has culminated in new investments in the region totalling approximately EUR 200 million, 300 new jobs, and significant research projects within the Seventh Framework Programme [

29].

In 2007, the Paper Province launched the Energy Square, the world’s first international centre for energy efficiency in the pulp and paper industry. Its aim was to simplify the process for developing new products and services that reduce energy consumption within the global pulp and paper industry [

25].

A big operational shift happened in 2013 when the Paper Province switched from traditional pulp and paper operations to a bioeconomy approach, “aiming to become a competence leader in Europe and a best practice example of the forest-based bioeconomy on a global scale”. This is expected to be achieved by developing a large-scale demonstration project that emphasises utilisation and a systemic approach. From a service perspective, the goal is to realise and industrialise new products and services based on new value chains within the forestry sector, as well as within other sectors [

30]. Furthermore, the Paper Province 2.0 intends to set the stage for 1000 new jobs and 25 new businesses during one decade [

31]. The strategy includes broader collaborations and a more efficient and complete innovation system, which is expected to lead to an increased number of innovations, start-ups, and establishments; increased equality; and increased knowledge in the surrounding world about how forests play a major role in the transition to a fossil-fuel-free society. This initiative will lead in the end to a reduced carbon footprint [

31].

The bioeconomy focus has resulted in decreased greenhouse gas emissions for the pulp and paper industry (−39% from 2008 to 2017) and at the same time an increase in processing value (+22% from 2008 to 2017) [

28]. The region now has more than 200 companies working in the forest-based bioeconomy. No other place in the world has such a high concentration of competence and expertise in pulp, paper, and packaging. There are 102 members in the cluster with 53 SMEs and 48 larger companies [

28].

The Paper Province initiative was established and financed in a triple helix arrangement. In addition to private companies, various other partners from the public sector, research, and civil society have supported the initiative. These include universities (mainly Karlstad University) and public actors, i.e., municipalities such as Region Värmland, VINNOVA, and the Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth (Tillväxtverket). VINNOVA, the Swedish Governmental Agency for Innovation Systems finances 50% of Paper Province activities, while the remaining 50% is co-financed by all the other public and private partners. Although the Paper Province member companies compete with each other, their cooperation is an added value, which allows for the development of the bioeconomy in the region (by concentrating knowledge and expertise and allowing regional growth) to benefit all.

The shared values created by the cluster for the local community can be identified at an economic, social, and environmental level, according to a survey of cluster members. More specifically, economic benefits include increased sales (creating increased profit) and the attraction of investors to the regions. Social benefits include increased collaboration regionally, nationally, and internationally; capacity building; hundreds of new jobs; an increase in research projects in collaboration with municipalities, universities, and technology centres; and increased equality and diversity. Environmental benefits include expending minimum amounts of energy and waste because all materials discarded by a process are utilised as inputs for another process and continuous improvements of the products reduce the impact from production and disposal.

Finally, it should be added that the Paper Province has a transformative project running to adapt to the effects of Corona. Paper Province, Compare, IUC/Steel and Workshop, and Karlstad Innovation Park offer support to small- and medium-sized companies in Värmland that have been affected by the COVID-19 crisis. Through the EU project “Adjust”, together with Karlstad Innovation Park, Compare and IUC/Steel and Workshop, they provide help to companies with up to 49 employees who wish to set up and innovate new products and services. The goal is to improve the conditions for companies in Värmlandin coping with the COVID-19 crisis in the short term. This is done by companies developing and strengthening their digital adaptability, their processes, and their products and expanding their customer offering for increased earning opportunities. In the longer term, the goal is to help companies strengthen their competitiveness and create the conditions for sustainable regional development. The project enables direct advisory and support efforts and includes three work packages designed according to identified needs in different industries.

4.6. Association “Partnership for the Barycz Valley”, Poland

The Partnership for the Barycz Valley (PDDB—“PartnerstwoDlaDolinyBaryczy”) is a Polish non-governmental organisation, active since 2008. It operates in eight communes located in the area of the BaryczRiver Valley, at the junction of the Lower Silesia and Wielkopolskie regions. This association is also a local action group, which brings together representatives of the public, economic, and social sectors as well as individuals. The association “Partnership for the Barycz Valley” is a spatially concentrated group of public institutions, enterprises, non-governmental organizations, and private individuals who work together to strengthen economic potential, increase tourist attractiveness, and increase the competitiveness of local business. Strong cluster connections have been created between these entities, making the association a cluster in all but name. The association deals with and shares its organizational experience in the activation of the local community, the development of entrepreneurship in accordance with its natural potential and respect for the principles of sustainable development, and environmental education [

32]. In addition, it manages the system of local promotion and quality assurance of products and services characteristic of the region called “Dolina BaryczyPoleca” (Eng. “The Barycz Valley Recommends”) [

32].

The Barycz Valley has been famous for many centuries for its large complexes of fish ponds (nowadays the largest in Europe), where the dominant direction of production is carp farming [

33]. This is a very valuable environmental territory, where the Landscape Park and NATURE 2000 area are located. Thanks to the large fishing ponds with fresh water fish production, valuable bird habitats unique on a European scale are located there [

32]. For this reason, this territory is particularly suitable for the development of sustainable tourism (understood as achieving economic benefits for the local community but with respect for wildlife and the protection of natural resources and human heritage [

34,

35,

36]), and carp and dishes made of it are the flagship products of the region and hold an important place among the products promoted by the “Dolina BaryczyPoleca” system. Currently, there is a growing group of consumers interested in combining tourism with the purchase of local dishes and regional products with unique features [

37,

38], so from the point of view of creating shared value, it should be noted that actions of PDDB linked with the “Barycz Valley Recommends” system are an excellent response to this market trend. It is worth adding that the EU introduced the legal and institutional framework for the development of the regional product market and shortening the supply chains [

39], and the “Barycz Valley Recommends” system as a local and bottom-up initiative fits perfectly into these assumptions and favours the creation of added value in the area of PDDB operations.

Bearing in mind the nature of local resources, the activities of PDDB create shared value for the region in the form of supporting the development of entrepreneurship, increasing local competitiveness, creating educational campaigns for residents, and promoting the region. This is done mainly by conducting calls for proposals, as well as advice and consultation for people interested in subsidies, co-financing of local events, and promotional materials.

For example, in 2018 the quantifiable effects of PDDB in terms of creating shared value in the region were: (1) 93 trainings for 1484 people (topics: information on grant programs, guidelines for writing business plans and the procedure for submitting applications for financial support); (2) individual consultations at work on the grant application (a total of 856 h during 103 contacts with applicants); (3) distribution of the educational grant “Education for the BaryczValley” for 17 NGOs, which carried out 257 trainings for 7554 participants (target group: teachers and students living in the Barycz Valley); (4) distribution of subsidies for 17 local enterprises for the creation and development of economic activity in the amount of PLN 2.413 million(funds from Rural Development Program for 2014–2020); (5) distribution of subsidies to21 entities from the fisheries sector for the development of economic activity, increasing the sector’s competitiveness and pro-environmental measures in the amount of PLN 3.389 million(funds from Fisheries and Sea Operational Program for 2014–2020); (6) transfer of PLN 0.5 million for establishing a local business incubator (funds from Rural Development Program for 2014–2020); (7) support for 51 exhibitors in the form of co-financing the costs of promotion and organization of “Carp Days” for the sum of PLN 43,000 (30% of the total cost of the event); (8) granting rights to use the “Dolina BaryczyPoleca” sign when promoting and selling 57 products and 101 services offered by local entrepreneurs; and (9) support for the promotion of the region and the development of the local brand by co-financing the production of promotional materials about the Barycz Valley (movie, leaflets, maps) in the amount of PLN86,000 [

40].

5. Discussion

As should be evident by their specialisation, all the case study clusters are primarily rural in nature. All of them are based on a mobilisation of local resources, whether to produce renewable energy or to produce food with added value by environmentally friendly agricultural methods. The most important common feature with regard to the main topic of this paper, however, is that all of these clusters are already creating shared value [

9] because their operating practices are designed to enhance their competitiveness and are simultaneously advancing economic, social, and environmental conditions in the communities in which they operate.

The cases presented above and summarised in

Table 1 demonstrate elements of shared value creation in all three different ways specified by Porter and Kramer [

9] (i.e., reconceiving products and markets, redefining productivity in the value chain, enabling local cluster development). Societal needs are served by developing better quality, healthier, or sustainable final products, whether they are energy or food products. The cases redefine productivity in the value chain by better utilisation of resources, employees, and business partners. Finally, the clusters in question clearly improve available skills, supplier bases, and supporting institutions in the communities where they operate to boost productivity, innovation, and growth [

10]. This is achieved both by their own nature as clusters, bringing different stakeholders and enterprises together and closer to society in the quadruple helix model, and by further networking actions that they perform in their regions, bringing R&D organisations closer to companies and professionals or closer to local authorities.

Virtually all of the cluster cases provide important benefits in terms of know-how, technology, or market reach to their members and this also tends to spill over to the local communities. This seems to be a result of the original plan which led to the creation of these clusters. Whether their creation was a public initiative or the result of the efforts of a local champion, the original actions were top-down and were aimed at boosting regional R&D activities and making the local economy more competitive and more sustainable.

CluBE, for example, has the key aim of developing R&D and business activities in the fields of bioenergy and environment in order to reinforce the green economy and aid its region’s transition, while CRPV was founded to advance research on crop production and protection as well as bioenergy and to modernise agriculture via ICT tools, development in genetics, and other state-of-the-art methods. Creating networks between research organisations is also one of the original objectives of the Cluster Food Industry. In every case, however, the clusters have reached a stage where private initiative driven by private interests has taken over or is taking over a major part of the responsibilities and energy needed for moving forwards. In essence, all the case study clusters were designed top-down in a way that was intentionally planned to meet the region’s economic, social, and environmental needs. This is one of the potential benefits of this top-down design process and one that makes it inherently well suited for the creation of shared value. The fact that these clusters went on to grow and flourish regardless of public support shows that meeting the region’s economic, social, and environmental needs successfully coincides with the target of the clusters’ own development and profitability.

This means that shared value [

8] (defined as a combination of economic competitiveness with beneficial social consequences) is essentially a direct result of the primary aims set by the clusters’ founders, but in doing so they have formed an agenda or framework which the cluster members, including private enterprises, are also willingly pursuing on their own, propagating the creation of shared value. Still, in these cases, this combination is also facilitated by the fact that the sectors in which these clusters operate (i.e., bioenergy, bioeconomy, sustainable agro-food) are sectors which are predisposed towards producing environmental and social benefits. Unsurprisingly, size and geographical coverage also play a key role in this. Larger clusters, with more members, more employees, more public authorities, NGOs, and research organisations involved, and covering a wider geographical area, will have a greater social and environmental impact in their regions.

The problem, however, is that measuring the result in order to measure shared value “objectively” is dependent on each individual case. There is no specific set of indicators or measurement scale in the literature which can be used to measure shared value. Porter et al. [

41] provide a comprehensive list of business and social results which can be used for the assessment of shared value per level (reconceiving products and markets, redefining productivity in the value chain, or enabling cluster development), but the list of results comes with two different challenges. First of all, some of the results, especially the social ones, are difficult to measure numerically (e.g., improved job skills or improved nutrition). Second, even with the results which are straight forward to measure (e.g., increased revenue for enterprises or increases incomes for local residents), it is difficult to demonstrate the extent to which they are the direct result of shared value as opposed to external variables.

With regard to the six case studies of clusters creating shared value presented in this paper, the benchmarking of the economic and social results they produce would entail the development of a specific set of indicators for each cluster, according to its specific impacts in terms of shared value, and then obtaining suitable data in order to assess the indicators over a specific length of time in order to demonstrate impact. This would mean developing a whole new taxonomic measure. In addition, broadening the scope of the study to include more case studies of clusters and networks from Europe would allow for the collection of quantitative data which would show how the network structure, location, size, and activity domain of each case can affect the efficiency of its cluster, the needs of its members, and the creation of shared value. This can result in the development of a new model or measure of cluster shared value based on specific “diagnostic” variables.

Finally, another factor holding back the present paper from producing more specific measures of shared value is that, as acknowledged, the research on the exact relationship between shared value and clusters is still in its infancy [

16]. This means that, at least, the conclusions of this paper could add to the existing body of research on this topic and gradually lead to a better understanding which would also allow for precise benchmarking.

6. Conclusions

Overall, the theory on shared value, its application on clusters and networks, and the overview of the selected case studies shows that clusters have an extremely promising potential for the creation of shared value in rural areas. First of all, clusters, due to their collective nature and collective action, are in the ideal position to meet several of the prerequisites for creating shared value, especially when they involve not only the private sector, but other actors as well, such as trade associations, government agencies, and NGOs [

9]. This is the case for the clusters studied above. Apart from being well suited for the creation of shared value, clusters are also inherently well suited for the creation of rural prosperity and sustainability [

42]. The type of data obtained for the six case clusters are data which demonstrate the creation of shared value according to the definition created by Kramer [

9] (i.e., advancing the economic and social conditions in the communities in which the cluster operates). Moreover, clusters, with their multi-actor approach along the rungs of the triple and quadruple helixes, can be ideal for covering the more geographically sparse rural areas.

Second, the sectors in which the case study clusters are active—namely, agro-food, bioenergy and bioeconomy in general—are extremely innovative sectors. They belong to the priority sectors set by the European Cluster Observatory, making them ideal for Porter and Kramer’s [

9] original (and highly ambitious) premise of using shared value to reinvent capitalism and unleash a wave of innovation and growth. In addition, these sectors are extremely well suited for the creation of shared value, since value for society is created through the fulfilment of such social needs as health, better housing, and environmentally friendly products and operations [

9]. Regarding the specialisation of the cases examined here, the environmental benefits of bioenergy should be extremely clear [

43], while research also shows that agriculture can have major social benefits, especially in terms of health [

44].

Finally, the role of clusters in the creation of shared value is also demonstrated by the six case studies examined. The clusters in question produce several social and environmental benefits as an integral part of their business strategies. This should be clear by their contributions to the education and training of the local workforce, the creation of new jobs, the improvement of local incomes, the production of sustainable energy, and the production of healthy, sustainable, and additive-free food, etc.

The present paper is, as far as the authors are aware, the first instance of shared value being assessed in several different cases of clusters. Of course, as the discussion pointed out above, there are still considerable research gaps, and a whole new benchmarking methodology needs to be developed in order for shared value to be assessed in greater detail in practice.

In short, however, the present paper demonstrates that rural areas offer the right conditions in which to develop clusters, especially within the sectors of bioenergy, bioeconomy, and agro-food. These in turn are ideal for the creation of shared value. This means that clusters, with their potential for shared value creation, can constitute a powerful engine for the sustainable revitalisation and development of rural areas in the EU (and the world), addressing the significant challenges which these areas are currently facing [

3].