Ageing in Place in Disaster Prone Rural Coastal Communities: A Case Study of Tai O Village in Hong Kong

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Rural Coastal Communities at the Forefront of Population Ageing

1.2. Rural Coastal Communities at the Frontline of Climate Change

1.3. Ageing in Place within the Context of Disaster-Prone Rural Coastal Communities

1.4. Knowledge Gap and Situating This Study

- (1).

- In what ways are the older residents (65+) attached to Tai O village as a place to age?

- (2).

- What are the facilitators and challenges to age in place for these residents?

- (3).

- How do disasters impact aging in place for these residents?

- (4).

- What supports do they access and use to reduce the impacts of disasters?

1.5. Conceptual Framework: The Disaster Risk Reduction Cycle

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Site: Tai O Village in Hong Kong

2.2. Recruitment and Sample

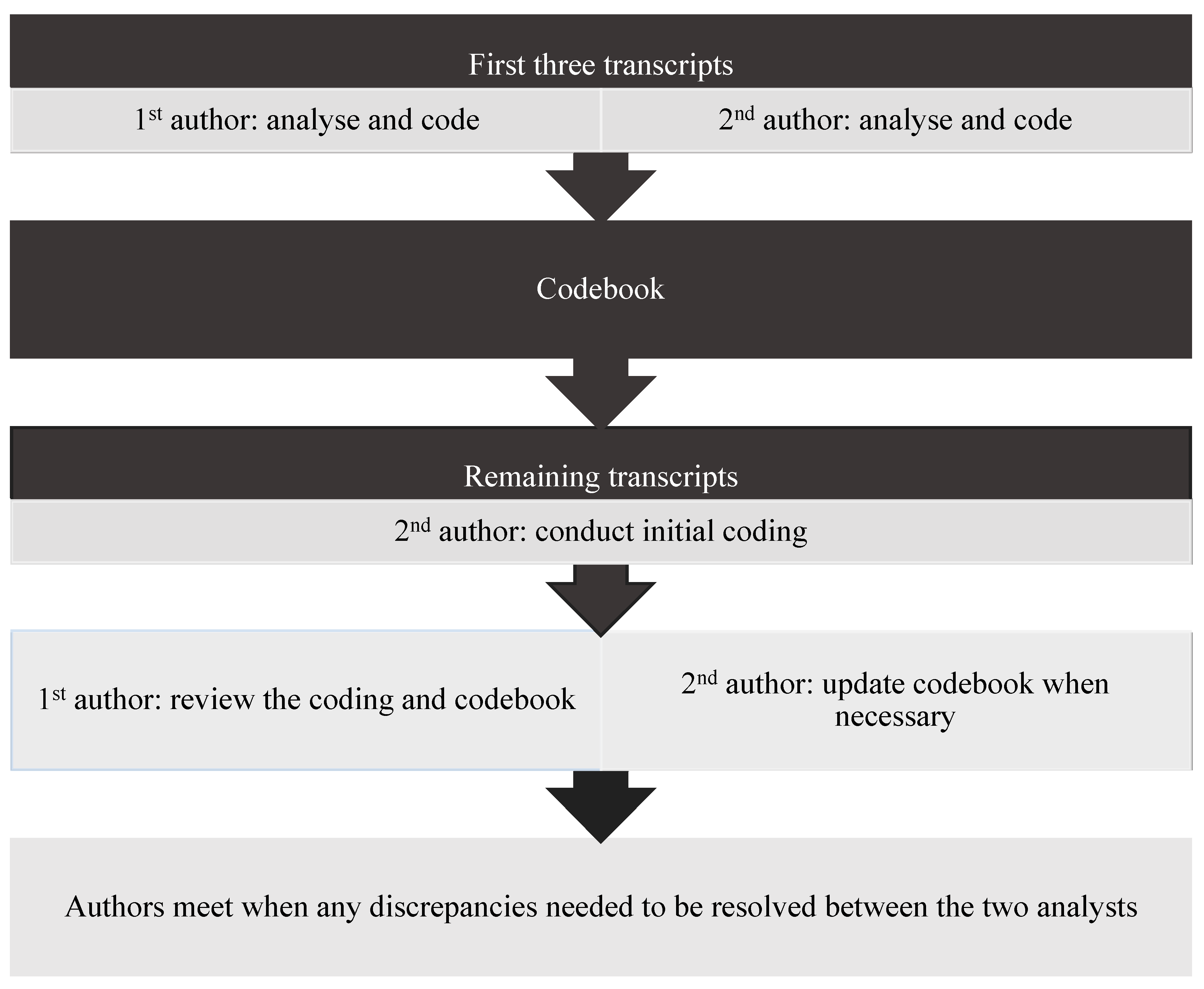

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis Methods

3. Results

3.1. Research Question #1: In What Ways Are the Older Residents (65+) Attached to Tai O Village to Age in Place?

3.2. Research Question #2: What Are the Facilitators and Challenges to Age in Place for Rural Coastal Older Residents?

3.2.1. Theme: “Work Is Inner Sustenance”

3.2.2. Theme: Social Participation

3.2.3. Theme: Health/Mobility Issues and Living in Stilt Houses

Sub-Theme: Need to Travel to the City for Health Services

Sub-Theme: Limited Ability to Refurbish/Maintain Homes

3.2.4. Theme: Social Support during Non-Disaster Times

Subtheme: Family Social Support during Non-Disaster Times

Subtheme: Government

Subtheme: Non-Governmental Organizations

3.3. Research Question #3: How Do Disasters Implicate Aging in Place for These Residents?

3.3.1. Theme: Damages/Losses Related to Home and Work/Livelihood

3.3.2. Theme: Disaster Preparedness Is Physically Taxing

3.3.3. Theme: Disaster Response and Recovery Is Physically Taxing

3.4. Research Question #4: What Resources and Supports Do They Access and Use to Reduce Disasters’ Impacts?

3.4.1. Theme: Resources and Supports for Disaster Preparedness (Pre-Impact)

Sub-Theme: The Third Sector and Civil Service Officers’ Key Role

Sub-Theme: Family Support Limited during This Phase

Sub-Theme: Self-Reliance

3.4.2. Theme: Resources and Supports for Disaster Response and Recovery

Sub-Theme: The Third Sector Plays Key Role in Recovery

Sub-Theme: Government Support Limited

Sub-Theme: Family Support during This Time Is Limited

Sub-Theme: Self-Reliance and Difficult to Ask for Help

3.4.3. Theme: Resources and Support for Mitigation

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. World Population Ageing 2019 (Report No. ST/ESA/SER.A/430). 2019. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/ageing/WorldPopulationAgeing2019-Report.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2021).

- Astill, S. Ageing in remote and cyclone-prone communities: Geography, policy, and disaster relief. Geogr. Res. 2017, 55, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayliss, J.; Sly, F. Ageing across the U.K. Reg. Trends 2010, 42, 2–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawchenko, T.; Keefe, J.; Manuel, P.; Rapaport, E. Coastal climate change, vulnerability and age friendly communities: Linking planning for climate change to the age friendly communities agenda. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 44, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. The aging trend analysis for the rural coastal zone in Shanghai. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Business Management and Electronic Information, Guangzhou, China, 13–15 May 2011; Volume 4, pp. 702–709. [Google Scholar]

- Wiles, J.L.; Leibing, A.; Guberman, M.N.; Reeve, J.; Allen, R.E.S. The Meaning of “Aging in Place” to Older People. Gerontologist 2011, 52, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, M.P.; Simon, B. The ecology of social relationships in housing for the elderly. Gerontologist 1968, 14, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawton, M.P.; Nahemow, L. Ecology and the Aging Process. In the Psychology of Adult Development and Aging; Eisdorfer, C., Lawton, M.P., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1973; pp. 619–674. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton, M.P. Environment and aging: Theory revisited. In Environment and Aging Theory: A Focus on Housing; Scheidt, R.J., Windley, P.G., Eds.; Greenwood Press: Westport, CT, USA, 1998; pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Vasunilashorn, S.; Steinman, B.A.; Liebig, P.S.; Pynoos, J. Aging in Place: Evolution of a Research Topic Whose Time Has Come. J. Aging Res. 2011, 2012, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurjonas, M.D. A Framework for Rural Coastal Community Resilience: Assessing Diverse Perceptions of Adaptive Capacity for Climate Change. Ph.D. Thesis, North Carolina State Univiersity, Raleigh, NC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- International Institute of Rural Reconstruction (IIRR). Participatory Methods in Community-Based Coastal Resource, Volume 1 Introductory Papers; International Institute of Rural Reconstruction: Silang, Philippines, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kapucu, N.; Hawkins, C.V.; Rivera, F.I. Disaster Preparedness and Resilience for Rural Communities. Risk Hazards Crisis Public Policy 2013, 4, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of United Kingdom (GovUK). An Evidence Summary of Health Inequalities in Older Populations in Coastal and Rural Areas. 2019. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/824723/Health_Inequalities_in_Ageing_in_Rural_and_Coastal_Areas-Full_report.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2021).

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Sea level rise and implications for low-lying islands, coasts and communities. In Special Report: Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate; Weyer, N.M., Ed.; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 321–445. [Google Scholar]

- Jurjonas, M.; Seekamp, E. Rural coastal community resilience: Assessing a framework in eastern North Carolina. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2018, 162, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B. Climate Change Impacts on Rural Poverty in Low-Elevation Coastal Zones. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2015, 165, A1–A13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astill, S.; Miller, E. ‘The trauma of the cyclone has changed us forever’: Self-reliance, vulnerability and resilience among older Australians in cyclone-prone areas. Ageing Soc. 2016, 38, 403–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukvic, A.; Gohlke, J.; Borate, A.; Suggs, J. Aging in Flood-Prone Coastal Areas: Discerning the Health and Well-Being Risk for Older Residents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwan, C.; Walsh, C.A. Seniors’ disaster resilience: A scoping review of the literature. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2017, 25, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coetzee, C.; van Niekerk, D. Tracking the evolution of the disaster management cycle: A general system theory approach. J. Disaster Risk Stud. 2012, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. 2015. Available online: https://www.undrr.org/publication/sendai-framework-disaster-risk-reduction-2015-2030 (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Stake, R.E. The Art of Case Study Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Islands District Council (IDC). Paper T&TC 55/2019. In Minutes of Meeting of Traffic and Transport Committee 22 July 2019. Available online: https://www.districtcouncils.gov.hk/island/doc/2016_2019/en/committee_meetings_minutes/TTC/TTCmin0722.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (GovHK). Preventing Coastal and Low-Lying Locations from Being Affected by Storm Surges and Flooding. 2018. Available online: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/201810/24/P2018102400648.htm (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- GovHK. Hong Kong Poverty Situation Report 2019. 2020. Available online: https://www.statistics.gov.hk/pub/B9XX0005E2019AN19E0100.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- De Silva, M.; Kawasaki, A. Socioeconomic Vulnerability to Disaster Risk: A Case Study of Flood and Drought Impact in a Rural Sri Lankan Community. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 152, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sixsmith, J.; Fang, M.L.; Woolrych, R.; Canham, S.; Battersby, L.; Ren, T.H.; Sixsmith, A. Ageing-in-Place for Low-Income Seniors: Living at the Intersection of Multiple Identities, Positionalities, and Oppressions. In The Palgrave Handbook of Intersectionality in Public Policy; Hankivsky, O., Jordan-Zachery, J.S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2019; pp. 641–664. [Google Scholar]

- White, G.; Singh, T.; Caine, K.; Connelly, K. Limited but satisfied: Low SES older adults experiences of aging in place. In Proceedings of the PervasiveHealth’15: Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare, Istanbul, Turkey, 20–23 May 2015; pp. 121–128. [Google Scholar]

- GovHK. Table 1A: Population by Sex and Age Group. Census and Statistics Department. 2021. Available online: https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/web_table.html?id=1A&download_csv=1 (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- GovHK. Hong Kong Annual Digest of Statistics. Census and Statistics Department. 2020. Available online: https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/en/data/stat_report/product/B1010123/att/B10101232020AN20B0100.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- Clarke, V.; Braun, V. Thematic analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017, 12, 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Laboy, M.; Severson, N.; Perry, A.; Guilamo-Ramos, V. Differential Impact of Types of Social Support in the Mental Health of Formerly Incarcerated Latino Men. Am. J. Mens Health 2014, 8, 226–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heisler, W.; Bandow, D. Retaining and engaging older workers: A solution to worker shortages in the U.S. Bus. Horizons 2018, 61, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, C. Factors and processes in the pre-disaster context that shape the resilience of older women in poverty. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 48, 101610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, A.; Durepos, G.; Wiebe, E. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research. In Encyclopedia of Case Study Research; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kohn, R.; Levav, I.; Garcia, I.D.; Machuca, M.E.; Tamashiro, R. Prevalence, risk factors and aging vulnerability for psychopathology following a natural disaster in a developing country. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2005, 20, 835–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Huang, W.; Huang, C.; Hwang, H.; Tsai, L.; Chiu, Y. The impact of the Chi-Chi earthquake on quality of life among elderly survivors in Taiwan—A before and after study. Qual. Life Res. 2002, 11, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pietrzak, R.H.; Southwick, S.M.; Tracy, S.; Galea, F.H. Posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and perceived needs for psychological care in older persons affected by Hurrican Ike. J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 138, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Participants (n = 12) | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 9 |

| Male | 3 |

| Age | |

| Young-old (65–74) | 5 |

| Middle-old (75–84) | 5 |

| Old-old (85+) | 2 |

| Place of birth | |

| Hong Kong | 11 |

| Macau | 1 |

| Language spoken | |

| Cantonese | 12 |

| Living arrangements | |

| With spouse | 7 |

| With spouse and kin | 3 |

| With friends and other | 2 |

| Housing type | |

| Privately-owned houses | 12 |

| Subsidized public housing | 1 * |

| Marital Status | |

| Married | 10 |

| Single | 1 |

| Widowed | 1 |

| Education level | |

| No formal education | 7 |

| Less than primary (less than six years) | 3 |

| Primary | 1 |

| Secondary | 1 |

| On government social assistance | |

| SSA Scheme | 11 |

| OPS | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kwan, C.; Tam, H.C. Ageing in Place in Disaster Prone Rural Coastal Communities: A Case Study of Tai O Village in Hong Kong. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4618. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094618

Kwan C, Tam HC. Ageing in Place in Disaster Prone Rural Coastal Communities: A Case Study of Tai O Village in Hong Kong. Sustainability. 2021; 13(9):4618. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094618

Chicago/Turabian StyleKwan, Crystal, and Ho Chung Tam. 2021. "Ageing in Place in Disaster Prone Rural Coastal Communities: A Case Study of Tai O Village in Hong Kong" Sustainability 13, no. 9: 4618. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094618

APA StyleKwan, C., & Tam, H. C. (2021). Ageing in Place in Disaster Prone Rural Coastal Communities: A Case Study of Tai O Village in Hong Kong. Sustainability, 13(9), 4618. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094618