The purpose of our research was based on the literature and the theoretical research model to examine the acceptance of the proposed payment interface to facilitate the payment process, to explain the use of multiple payment systems, and to compare it to an interface payment offered by the GCWB. In this research, the collected data was analyzed, processed, and tested to determine user satisfaction as the critical factor in using the new payment interface, which supports multiple payment systems.

6.1. Discussion of Findings

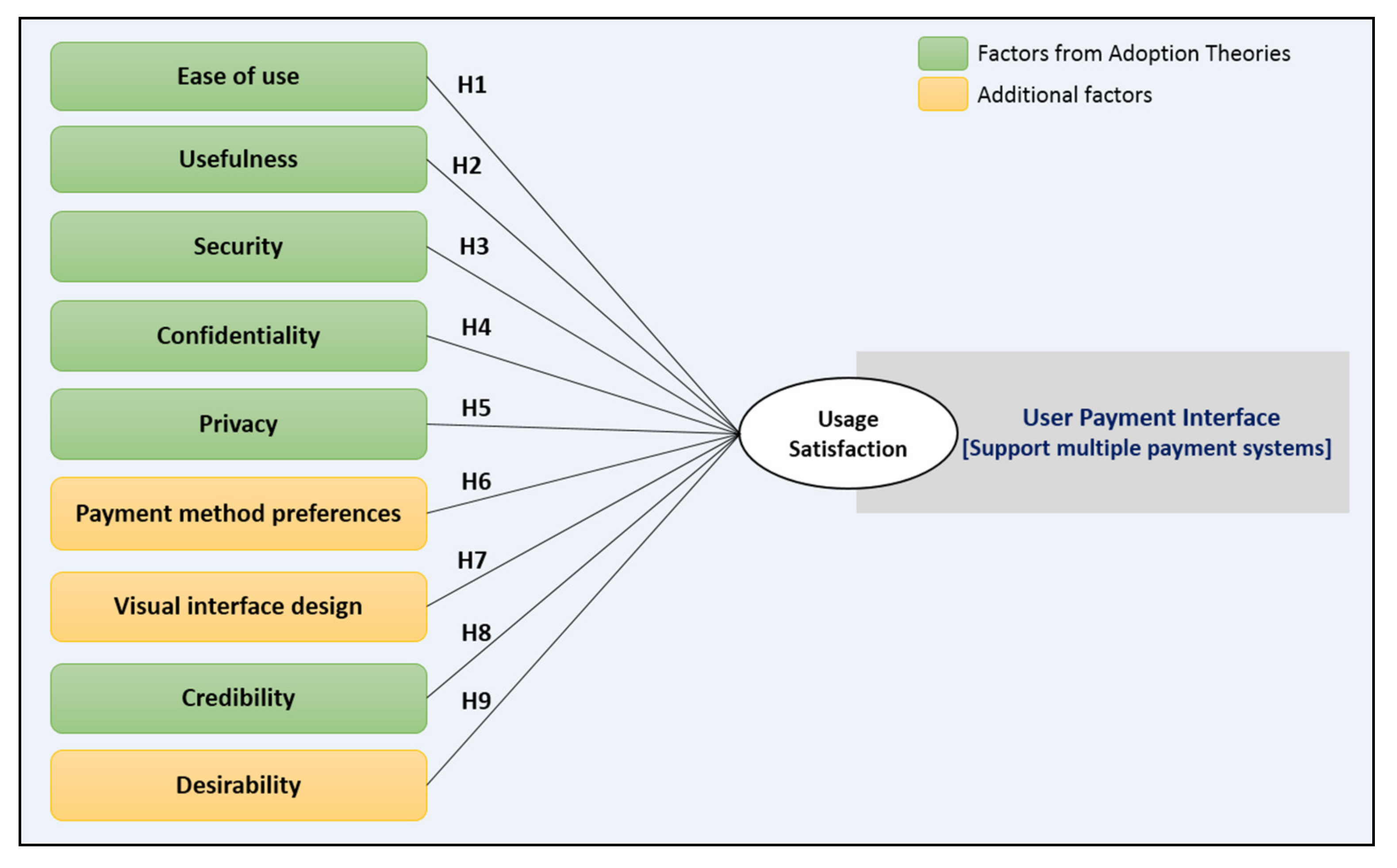

In this study, we tried to identify the characteristics that directly influence the satisfaction and acceptance of the payment interface. The study attempted to deploy the user preference literature in (M)EPS to predict satisfaction using the proposed payment interface. The validation of the use was completed using an online questionnaire and the data collected. Then, an in-depth multivariate statistical analysis was used to confirm the proposed research objective.

A generic sample of 266 responses matching the data, a gender balance (male 41.4% and female 58.6%) can be observed, which means that the gender of the respondents influences the reasons for starting the use of the payment interface. Two age groups dominate in this study, (18–25) (39.8%) and (26–35) (41%), who had a higher education level (secondary and university) (98.1%), which means that these groups are made up of people who are frequent users of (M)EPS. Besides, 5.2% of participants who answered the questionnaire are over 46 years old, confirming that there are people of this age group interested in the (M)EPS (

Table 1). Remarkably, our first result suggests that there is a relationship among demographic characteristics (gender, age, and educational level) and intention to use the new payment interface, as the results found by Tounekti et al. (2019) [

2], that gender, age, and educational level have a significant effect on the choice of payment methods, as well as on online consumer’s behavior. These respondent profiles used the internet (45.5%) to buy products and services between 1 and 2 times per month (

Table 2). Therefore, it can be concluded that the same group of respondents agree to use our proposed payment interface. The same group seeks to have a payment interface that supports more than one payment method and meets their needs and preferences [

2].

On the other hand, our research objective was to compare the current payment interface offered by the GCWB with our new payment interface taking into consideration user satisfaction. The questionnaire results presented in

Table 3 showed the frequency of participants (the group of respondents who choose the new payment interface) satisfied and very satisfied are 96% and 4% neither satisfied nor dissatisfied. Then, the participant frequency (the group of respondents who choose the current payment interface) that were satisfied and very satisfied is 48%, 20% neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, and 32% very dissatisfied/dissatisfied with the current payment interface (

Table 3). Besides, comparing between the present and new payment interface, the number of participants satisfied and very satisfied with the proposed payment interface is higher with 123 (48.04%) responders, over 82 (32.04%) responders dissatisfied and very dissatisfied, and 51 (19.92%) responders neither satisfied nor dissatisfied with using the current payment interface (

Table 4).

This study used direct and indirect questions to examine the preferred payment interface composition. The chi-square independence test was used to determine if there is a relationship between the proposed new payment interface and the different features. Phi and Cramers V discovers the strength of this association (

Table 5). In general, many previous studies [

2,

21] confirm the importance of ease of use, which is one of the characteristics indicated in this study as a determining factor in the satisfaction of using the new payment interface (Pearson chi-square = 53.87, Phi/Cramer’s V = 0.45).

Results in

Table 5 show that other factors could also be important, payment method preferences (Pearson chi-square = 41.84, Phi/Cramer’s V = 0.397), security (Pearson chi-square = 38.9, Phi/Cramer’s V = 0.382), confidentiality (Pearson chi-square = 34.16, Phi/Cramer’s V = 0.350), usefulness (Pearson chi-square = 33.09, Phi/Cramer’s V = 0.353), privacy (Pearson chi-square = 24.78, Phi/Cramer’s V = 0.305), visual interface design (Pearson chi-square = 14.64, Phi/Cramer’s V = 0.235), and credibility (Pearson chi-square = 7.08, Phi/Cramer’s V = 0.163). This study also confirms that ease of use has the strongest relationship with the proposed new user payment interface (

p ≤ 0.001 and Phi/Cramer’s V > 0.25). On the other hand, credibility has the weakest relationship strength (

p > 0.01 and Phi/Cramer’s V = 0.163), explaining why respondents could not guess how the proposed interface is credible. Assessing each variable separately (

Table 6) to test the relationship between the new payment interface and the different characteristics, we can conclude that ease of use (80.82%), security (75.93%), payment method preferences (72.93%), usefulness (67.66%), visual interface design (67.66%), privacy (65.41%), and confidentiality (60.9%) are the most important characteristics for the users to accept using the new payment interface, and, finally, the least valued characteristic is credibility (47.36%).

In line with this, Tounekti et al. (2019) [

2] found in their recent research that there is a relationship between the most convenient web browsers, the payment method on desktop and mobile phone and the payment features. Then, many researchers have observed that consumers’ factors were the active guide for using a payment method [

2]. Therefore, results in

Table 7 show that a large number of respondents (89.8%) are satisfied and very satisfied with using the new payment interface, and they are also ready and willing to use this new payment interface in their future payment transactions (

Table 7). Therefore, 37.6% of respondents use and wish to use the current payment interface offered by the GCWB in their future payment transactions. Additionally, 35% of this group of respondents were dissatisfied with the use of this payment interface. We can conclude that some participants are currently using the GCWB payment interface and that they are satisfied with using it and want to continue using it in the future, but, with the same percentage of other groups, they are not satisfied with the use of the current payment interface. They do not wish to use it in the future (

Table 8). The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) values were 0.7, consecutively greater than 0.5, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (

Table 9), which is significant at 0%, the use of factor analysis and principal component analysis (PCA) was justified. The eigenvalues were greater than 1, which proved each component variable’s adequacy to explain the variance of the dependent variable (intention to use the new payment interface) (

Table 10).

A recent study by Tounekti et al. (2019) [

2], has determined that many people who support and use more than one payment method want to see their preferred payment method when shopping online. Consistent with this, our results showed that we have the highest frequency of group participants who used at least three types of payment systems (54.14%) satisfied with our proposed payment interface and willing to using it in their future online transactions (

Table 11). Besides, we found that there is a relationship between payment interface user satisfaction, participant supporting multiple (M)EPS, and payment method preference factors by 93.75% of groups of a participant who support various payment systems (144 out of 266 participants), confidentiality (90.27%), usefulness (88.88%), visual interface design (84.72%), ease of use (83.33%), credibility (76.38%), security (58.33%), and finally privacy with 47.22% of this group of participants (

Table 12).

The model summary for multiple regression analysis is illustrated in

Table 13, was developed to identify the value of R square, which explains the explainability of the model. In this model, the value of R square is 0.546 for the construct usage satisfaction for the new proposed payment interface, which interprets that ease of use, usefulness, security, privacy, confidentiality, payment method preferences, visual interface design, and credibility variables can explain the variance towards predicting usage satisfaction to the extent of 54.6%; therefore, this model is accepted. The results in

Table 13 show that the adjusted R-square was 0.529, or 52.9% of the variance was explained by the nine factors (ease of use, usefulness, security, payment method preferences, privacy, confidentiality, visual interface design, and credibility), which is treated a good fit scale for the regression model.

Based on the regression analysis (

Table 14), eight of the independent variables (ease of use (B = 0.232,

p = 0.002), usefulness (B = 0.232,

p = 0.002), confidentiality (B = 0.329,

p = 0), visual interface design (B = 0.14,

p = 0.059), security (B = 0.329,

p = 0), payment method preferences (B = 0.183,

p = 0.009), credibility (B = 0.147,

p = 0.048), and privacy (B = 0.149,

p = 0.045)), are statistically significant predictors of users’ acceptance to use the new payment interface, and the consecutive assumptions are accepted (

Table 15). The desirability factor is not statistically significant (negative relationship) with the standardized regression coefficient B = −0.107 (

p = 0.148); the hypothesis is rejected, that means, desirability is not seen as a major challenge for the potential customer on (M)EPS (

Table 15).

However, our analysis shown in

Table 15 indicates that in using the (M)EPS interface, eight factors such as ease of use, usefulness, security, privacy, confidentiality, payment method preferences, visual interface design, and credibility have more significant impacts. Subsequently, it was also identified that the remaining desirability factor had lesser effects.

Therefore, the hypothesis surrounding constructs such as ease of use, usefulness, security, privacy, confidentiality, payment method preferences, visual interface design, and credibility was significantly associated with user’s perception towards interface payment solutions. The significance value of this hypothesis was less than 0.05. Therefore, hypotheses such as H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, H6, H7, and H8 were accepted. However, the desirability (H9) hypothesis was not accepted because the

p-value of this relationship was more significant than 0.05. The result of the regression analysis is illustrated in

Table 14 and

Table 15.

On the other hand, first, security and confidentiality have the highest coefficient (B = 0.329,

p = 0), which reveals that it has an essential impact on the user preferred new payment interface, ease of use, and usefulness (B = 0.232,

p = 0.002) has the second rank in the importance for the user selection of his/her preferred payment interface. These results are consistent with similar research on accepting (mobile) electronic payments [

2,

16,

45,

46]. Most respondents mentioned security as an important feature of the new payment interface because security was associated with a specific trusted interface. Overall, 239 responses out of 266 responses (89.8% of respondents) mentioned the capacity to provide the predetermined service as a satisfactory characteristic of the new user payment interface.

6.3. Limitations and Future Research

The aim of our document is for the interface to facilitate the online payment process when the user supports multiple payment systems and, presumably, has a preferred payment system. For this reason, we designed questions to compare both the payment interface offered by the GCWB band our proposed payment interface. However, this question did not attempt to reach the usability of the two interfaces on a browser since our interface was offered as a static web mockup. Our research work has several limitations, which we mention below: 266 responses were collected. We applied survey analysis techniques and multivariate analysis, and we had limited control of the participants’ cultural and demographic backgrounds. This group of participants favors the new technologies and people accustomed to paying on the Internet, which uses (M)EPS, and therefore is less representative of users who can use these digital payment platforms less frequently. Besides, the survey (

Appendix A) was drafted in the English language because it was presented to a universal public. Therefore, these limitations should be resolved by providing questionnaires in multiple languages to respond to most people who speak languages other than English; to gain more participants, the questionnaire should be kept open for several weeks or months.

Thus, there are limits to using an online questionnaire as a data selection method because the survey is self-administered. As an outcome, the researcher has no control over the participants and cannot propel in-depth answers. We propose in our future research to make a dynamic and functional mockup where users can interact with the interface to check if their opinion would be the same as that of a simple mockup. A more specific feature might require a more detailed analysis. Future research could also further investigate the sources of satisfaction/dissatisfaction identified using qualitative methods and could further examine what constitutes the attributes of a new usable payment interface. It would also explore what elements are devoted to the perception of security in the context of (M)EPS. Future research should also consider the processing time of different payment methods, and it might be necessary to have more demographic variables on the questionnaire to provide more reliable results. The questionnaire could also be alternated to give some respondents more information, for example, on security issues related to payment methods.

In contrast, other respondents are expected to rely on their own experience and knowledge. Methodologically, the approach highlighted can be used in future studies for exploring theoretical models’ validation. This would exceptionally be relevant if data-driven inductive research is undertaken to contribute to the domain of (M)EPS. Future research can also improve upon this approach methodologically by developing strategies whereby better internal and external validity measures can be demonstrated.

Given its limitations, our research provides a vital launching pad for future research in different backgrounds investigating the aspects influencing consumers’ intentions to use (M)EPS. Our study opens up the possibility of sharing our results with the W3C payment and web standardization group to further improve the online payment domain, which accordingly with the current global COVID-19 situation, assuming people start using (M)EPS more than before, and subsequently demographic issues and preferences, with higher use of (M)EPS, may change. Therefore, it would be interesting to carry out further studies regarding the number of payment systems used, the number of transactions carried out occasionally, more payment systems, and the same problems and needs.