1. Introduction

The Central Axis of Beijing, as the epitome of the ancient Chinese axis, is an important part of urban culture and historical accumulation. The report of the 19th Communist Party of China National Congress points out that socialism with Chinese characteristics has entered a new era and has put forward new requirements for the protection of history and culture. As the maintainer of urban spatial order and the carrier of urban historical memory, values and spiritual culture, the protection and development of the Beijing central axis should not be limited to the past, but also consider the extension of the future.

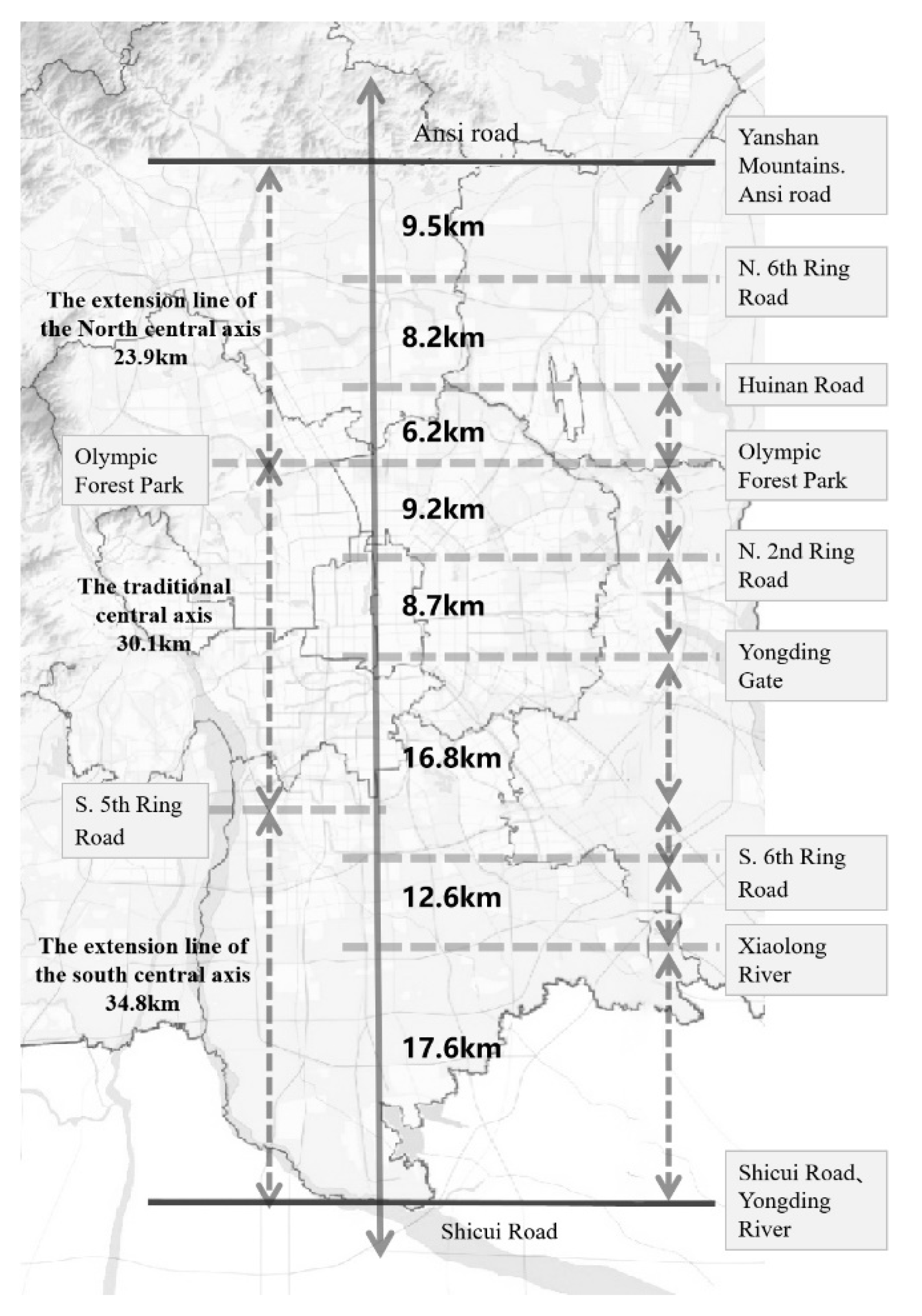

At present, the Central Axis of Beijing is based on the central axis of the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368). Driven by constructions during the Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) dynasties and the Republic of China, as well as the stimulation of the Asian Games, the Beijing Olympic Games and Nanyuan Airport after the founding of the People’s Republic of China, it expanded from 7.7 km in the Yuan Dynasty to 8.7 km in the Ming and Qing dynasties, and 16.2 km in the Republic of China, until 30.1 km nowadays. The Beijing municipal government has decided to extend the central axis southward and northward. It will be extended to 88.8 km long, from the Yanshan Mountains in the north and the new airport and Yongding River system in the south. It will also cover about 480 km2. The extensive extension of the central axis will have a deep impact on the overall structure and function of the central axis as well as the area along the central axis.

The Central Axis of Beijing has always been a hot topic for scholars, involving four research areas. First, the protection and renovation of important historical architectural heritage on the central axis [

1,

2,

3]; second, the protection of the overall style of the key nodes on the central axis [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8], and the style control of the streets along the central axis [

8,

9,

10,

11]; third, the environmental improvement of the areas around the central axis to improve people’s livelihood [

4,

11,

12,

13]; fourth, the industrial function positioning of the area around the central axis, and the tourism planning of it [

9,

14].

Since the 1990s, academia has gradually realized that heritage protection should not be limited to single buildings or historical blocks. It should be investigated systematically and comprehensively from broader regional backgrounds and more diverse social, cultural and ecological backgrounds [

15,

16,

17]. Therefore, the “Historical Urban Landscape” (HUL) came into being as a sustainable heritage protection method in the new century [

18,

19]. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) defines the HUL as a comprehensive method for the overall protection and management of urban areas under the sustainable development framework [

20]. It mainly consists of six critical steps: mapping the distribution of natural and cultural resources, defining the protection value and characteristics of heritage through public participation, vulnerability assessing of characteristics, integrating heritage into overall framework of urban development, prioritizing actions related to protection and development, and establishing a multi-party coordination mechanism for each protection and development project. It consists of four tools: public participation tools, knowledge and planning tools, regulatory system and financial tools [

21,

22,

23]. Since then, relevant scholars have expanded the analysis framework of the HUL from cultural mapping based on the concept of “historical layering” [

24], heritage value assessment based on the perspective of tourists and intangible cultural heritage and so on [

25,

26], and the impact of climate change on heritage vulnerability [

27]. Some scholars have further deepened the HUL analysis framework through the application of Geographic Information System (GIS) and other related technologies in heritage protection [

28], the impact of financial compensation and other policies on heritage protection [

29] and other ways. The HUL analysis framework has been widely used in heritage protection, and has carried out unique practices in Naples [

30], Florence [

31], Pingyao [

32], Taiyuan [

33], Taiwan [

34], etc. However, few scholars use the HUL method to analyze the Central Axis of Beijing.

Based on the HUL analysis framework, the paper constructs the overall framework including the dynamic cognition of the cultural stratification of the Central Axis of Beijing, the relationship between the central axis and Beijing’s macro landscape pattern and its changes, the relationship between the historical and cultural relics of the central axis and urban elements, and the property rights arrangement and public opinion analysis in the central axis governance. The paper also puts forward the overall management and control system of the North–South extension of the central axis, which includes nine aspects: control scope, extension direction, axial space, horizontal space, traffic, water system, green space and leisure system, context protection and governance system (

Figure 1).

2. Historical Evolution of China’s Central Axis

2.1. Concept of Central Axis

Ancient Chinese documents only provided interpretations and extensions of the word “axle”, the term “axis” is not mentioned clearly. The axis does exist when we are looking at our ancient architecture and capital planning. The original meaning of “axle” in ancient texts of

Cihai, the encyclopedia of the Chinese language, is “wheel axle” [

35], and then gradually extended definitions such as “center” and “pivot”. The Confucian literature

Classified conversations of Zhu Xi also further explained the characteristics of “pivot” such as “centering”, “immobility” and “north-south position”. In modern China, the term “axis” appeared in the

Collected essays of Liang Sicheng. He used the “main middle line” and the “central axis” to refer to the shape and structure of the “middle line” commanding the large building complex in ancient urban construction [

36]. As a linear spatial element that controls the spatial structure in the city [

37], the “axis” is an essential means of organizing the urban space, and it is also a dynamic factor for urban development [

38].

The difference between “central axis” and “axis” lies in the connotation of the word “central”. “Central” is the most core thought in Chinese traditional culture. The thought of worshiping the mean” was placed at the highest position in The Book of Changes, referring to the ability to grasp moderation and the process of making things optimal. Confucius inherited and developed the idea, integrated it with ethics, politics, philosophy, and other content, and brought forward the Doctrine of the Mean: “Equilibrium is the great foundation of the world”. As the basic principle of dealing with people and the highest standard of ethics and morality, the Doctrine of the Mean has influenced the social order of ancient China, and embodied in the concrete form of the “central axis” in the construction of the capital city. The central axis is a crucial means to embody China’s traditional thinking, social order, and spiritual culture to plan and construct the capital.

2.2. Development Stage of China’s Central Axis

The term central axis originated from modern times, but the word middle line has been used since ancient times [

39]. The middle line was used to design the architectural layout at first, and it was developed in the residence such as houses, courtyards and palace complexes, and gradually formed a symmetrical structural system through the central axis, which extended to the urban design level (

Figure 2).

2.2.1. Central Axis Guiding Layout of Buildings and Courtyards

Archaeological data show that architectural sites excavated in the Late Neolithic have already emerged in symmetrical shape through the middle line. The central axis was used to guide settlement layout and house construction [

40]. For example, the buildings unearthed from the later Yangshao Culture Site in Dadiwan had a relatively complete symmetrical shape through the central axis. The axis selected the master room and the backroom as the middle, and the side rooms were placed symmetrically on both sides. The palaces, ancestral temples and other buildings integrated with the social etiquette system, the concept of class, and patriarchal clan system in the Xia (c.21st century–16th century BC), Shang (c.16th century–11th century BC), and Zhou (c.11th century–256 BC) dynasties inherited the symmetrical shape through the middle line. The axis selected the gate courtyard and the palace as the middle, and the chambers or side halls were symmetrically arranged on both sides. Subsequent capitals have inherited this feature [

41].

2.2.2. Central Axis Guiding Layout of Building Complex

Palace complexes in the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties have the axial symmetrical shape. Archaeological data show that several large architectural ruins excavated from the Erlitou site in Yanshi, Henan province, which served as the Xia Dynasty’s capital, are closely related in their orientation, and maintain a unified architectural direction and planning axis [

42]. The axis selected the median line of the single palace building as the center and extended as the central axis of the palace complex, forming an architectural sequence in the axial space.

2.2.3. City’s Central Axis with Imperial Ancestral Temple as the Core

Capital cities of the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties also appeared in symmetrical shapes through the middle line. According to the city ichnography restored by archaeological data, there was a city central axis passing through the palace area in Yanshi Shan city. Its gates, roads, and palaces were laid out symmetrically [

43]. The city central axis during this period selected the ancestral temple as the middle. The basis is as follows:

Rites of Zhou The Artificers’ Record recorded that the most important elements in ancient capital cities were the imperial ancestral temple, the altar of land and grain, the court, and the market. From the

Yizhoushu Zuoluo, the construction sequence of the imperial ancestral temple took precedence over the palace [

44]. Academia generally believes that the palace’s status was lower than that of the imperial ancestral temple in Chengzhou [

45]. The imperial ancestral temples of the Western Zhou Dynasty (c.11th century–771 BC) and before were at the core in space.

Lyv’s Spring and Autumn Annals also pointed out that “the ancient emperors chose the middle of the world to build a country, chose the middle of the country to build a palace, and chose the middle of the palace to build the ancestral temple” [

46]. According to the information obtained from the city ichnography of the Erlitou site of the Xia Dynasty, Yanshi Shang city and other cities, there is only one palace area in the capital city site. It can be inferred that before the Western Zhou Dynasty, palaces and temples were placed together with the imperial ancestral temple as the core. The axis chose the imperial ancestral temple as the center and extended it to the entire capital city.

2.2.4. City’s Central Axis with Palace as the Core

During the Spring and Autumn Period (770–476 BC) and Warring States Period (475–221 BC), it was challenging to meet the demands of military defense only by building palaces outside the ancestral temple due to frequent wars in various countries, establishing another imperial palace and the construction of additional walls began to emerge. After that, the palace and the ancestral temple began to separate. The importance of the palace became more prominent, and the city axis in the capital city planning also began to select the main palace as the center. In the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC–AD 24), Chang’an City first appeared in the city central axis’s embryonic form which chose the palace as the center. The axis passed through the imperial palace with Hengmen Street in the north to the Xi’an Gate in the south. Royal academies, the altar of land and grain, the Twelve Temples of Wang Mang, and other ritual buildings were placed in the southern suburb outside the Peace Gate, locating on both sides of the central axis. However, the city central axis deviated from the city’s central position, and was not based on the main hall. In the Eastern Han Dynasty (AD 25–220), Luoyang City began to form the central axis of the imperial palace with the main hall as the base point, and then extended to the city central axis of the capital. The ritual buildings were still placed on both sides of the central axis in the southern suburb, and the palace axis and the city axis began to merge. During this period, the central axis was not in the center of the entire capital city. From the Western Han Dynasty to the Northern Wei Dynasty (AD 386–534), capital cities were mostly renovated on the sites of the old city, and the planning was constrained to accommodate. It was not until Ye City of the Wei Dynasty (AD 220–265) that the overall layout of city planning with the central axis placed in the middle and rigorous symmetry appeared, and it influenced the design of palaces in successive dynasties. It is worth mentioning that although the ancestral temples and altars in Ye City were placed in the city, they were not on the axis, but in front of the central government office outside Sima Gate on the east side of the axis. Since then, in the planning and construction of Chang’an City in the Sui (AD 581–618) and Tang dynasties (AD 618–907), Dadu City in the Yuan Dynasty, and Beijing City in the Ming and Qing dynasties, important ritual buildings were placed on both sides of the central axis of the city. A more rigorous building sequence of the central axis that better embodied the etiquette system’s fundamental national law was formed.

3. The Development Process of the Beijing Central Axis and its Core Influencing Factors

Axis is an important part of the construction of ancient capital city, and its development and evolution are closely related to the changes of the city site. The urban construction of Beijing is influenced by its macro landscape pattern. The mountains in Beijing present a basic pattern of mountains on three sides, five rivers flowing through them, and open to the southeast. Moreover, the mountains and water systems intersect, which together constitute an excellent landscape pattern of wind and gas are trapped and mountains are surrounded by water. This is also in line with the principle of site selection in ancient Chinese tradition of Yin and Yang embracing together, back mountain facing water. Under the influence of this excellent geographical advantage, the Liao, Jin, Yuan, Ming and Qing Dynasties successively established their capitals here, and their city central axis also evolved. Throughout the history of development of Beijing, there have been two central axes, namely, the central axis of Nanjing of the Liao Dynasty and Zhongdu of the Jin Dynasty, which are located in the West 2nd Ring Road, and the central axis of Dadu of the Yuan Dynasty and Beijing City in the Ming and Qing dynasties, which run through Drum Tower to Yongding Gate. This chapter selects six typical periods to sort out the evolution process of Beijing’s “city” and “axis”, and summarizes the development process of the Beijing central axis and its influencing factors (

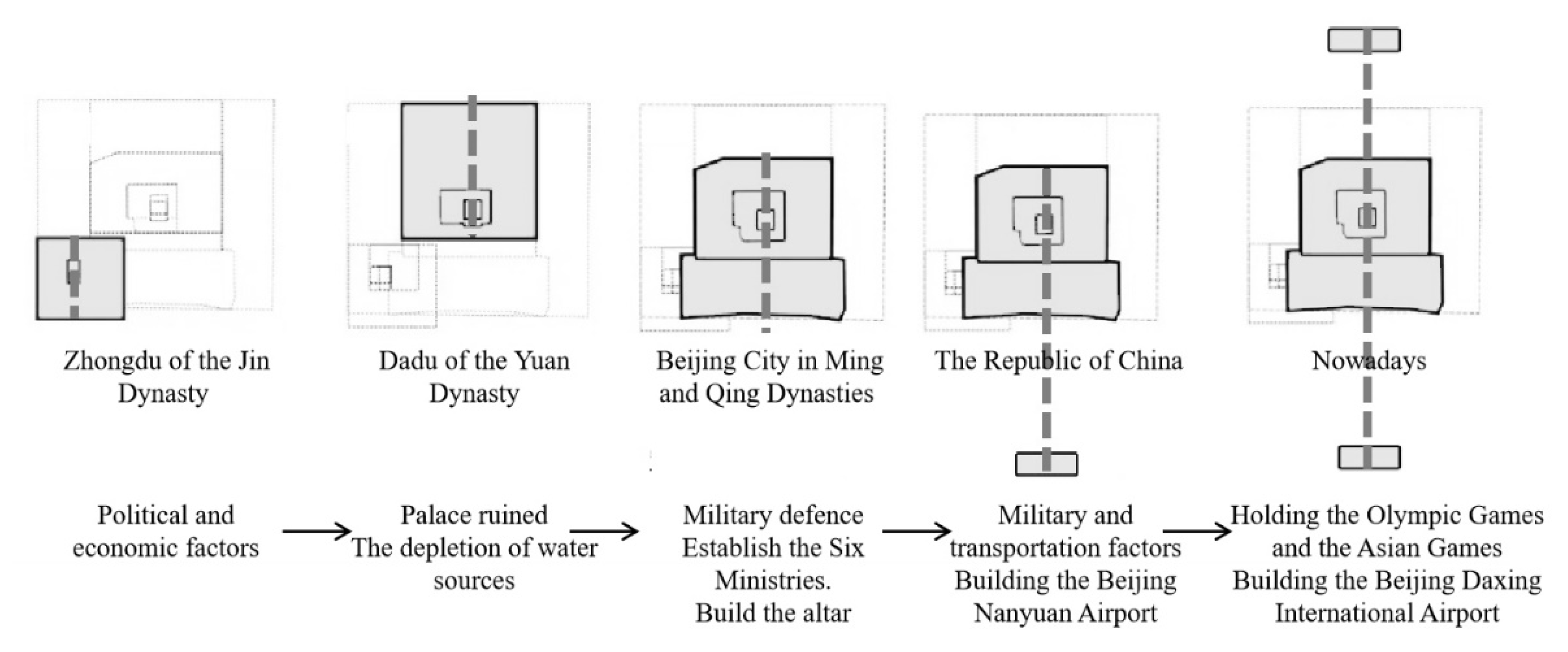

Figure 3).

3.1. Evolution of Jin Dynasty’s Central Axis

Ji City in the Xia and Shang dynasties was the earliest embryonic form of Beijing City’s spatial layout. Ji City was built at the intersection of ancient roads with an excellent pattern of mountains and rivers. It had a very high strategic position, and laid the foundation for the construction of cities of the Liao and Jin dynasties. The history of Beijing’s establishment as the capital can be traced back to the Jin Dynasty. Because Shangjing City of the Liao Dynasty was located in a remote place, which was not conducive to the country’s rule and economic exchanges with the Central Plains area, the rulers of the Jin Dynasty decided to move the capital to Beijing. The Zhongdu City of the Jin Dynasty was built on the West Lake water system (now the Lianhuachi water system). Because the river restricted the development of the north, Zhongdu city could only be expanded to the east, south, and west by 3 li (1500 m) on the basis of Nanjing of the Liao Dynasty. It imitated the Bianliang city of the Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127) with the layout of the palace city in the center, forming the central axis of the Zhongdu of the Jin Dynasty.

3.2. Evolution of Yuan Dynasty’s Central Axis

In the Yuan Dynasty, due to the ruin of the palace in Zhongdu and the exhaustion of water sources, the old site was abandoned, and the new one was moved to the nearby of the Gaoliang River system with abundant water sources, and Dadu of the Yuan Dynasty was established. A central pavilion was set up on the north side of the water system at the same time to establish the initial center point of the central axis, which laid the foundation for the formation of the present Central Axis of Beijing. The central axis of the Yuan Dynasty’s Daduis was about 7.7 km long. It had two sections: the central axis of the palace city and the central axis of the outer city, which do not coincide (

Figure 4). In this period, the city reflected spatial order through wide arterial roads and several city gates, and the symmetrical shape through the central axis presented an orderly spatial layout [

47].

3.3. Evolution of Ming and Qing Dynasties’ Central Axis

The Central Axis of Beijing of the Ming Dynasty was designed and revised based on the central axis of Dadu of the Yuan Dynasty [

48]. Due to military defense, the establishment of the Six Ministries and the construction of temples (the Temple of Heaven and the Temple of Agriculture), city walls of the Ming Dynasty went through three changes. The northern wall retreated 5 li (about 3000 m in Ming Dynasty), the inner-city wall expanded 1 li to the south, and the outer city was built. Eventually, city walls of the Ming Dynasty completed the transformation of the spatial layout from a square shape to a “convex” shape, and the central axis moved southward as a whole (

Figure 5). The city pattern of Beijing City of the Qing Dynasty followed that of the Ming Dynasty and was rarely changed. The spatial structure of the central axis of the imperial palace that ruled the city has also been confirmed. Compared with the traditional central axis of the Yuan Dynasty, the Central Axis of Beijing of the Ming and Qing dynasties extended to 8.7 km. The outer city’s central axis extended from the imperial palace to Yongding Gate, and the traditional central axis of the outer city of the Yuan Dynasty in the north was shortened to Jishuitan. During this period, the two sections of the central axis were unified (

Figure 6), and the six main halls were located on the central axis, making the architectural sequence of the palace city more compact and the spatial layout more rigorous. The establishment of the two rigorously symmetrical etiquette building groups, the imperial ancestral temple and the altar of land and grain, incorporated the entire section between the Meridian Gate and the Chengtian Gate in the south of the imperial city into the overall planning of palace buildings, highlighting the axial road. Symbolic buildings such as the Bell Tower and city gates further enhance the overall architectural sequence of the central axis [

49]. In the end, a spatial order with symmetrical buildings with varying heights, rich and diverse landscapes, and rigorous and varied spatial layout was presented [

47].

3.4. Evolution of the Republic of China’s Central Axis

Considering factors such as military and transportation during the Republic of China, the Beijing Nanyuan Airport was built at the southern end of the central axis, laying the foundation for the central axis to extend southward. The central axis was 16.2 km long and was divided into four sections (

Figure 7). City walls of the original imperial city were demolished in a large area at this time. The central axis began to break through the closed state, and the original imperial private space was progressively opened to the public.

3.5. Evolution of Central Axis from Founding of the People’s Republic of China to 1976

From the founding of the People’s Republic of China to 1976, the central axis continued the Republic of China’s spatial layout. Landmark buildings such as Yongding Gate and Di’an Gate on the central axis have been demolished due to population growth and traffic congestion. The unique architectural sequence and imperial power attribute of the central axis have been destroyed, and the spatial structure has also been transformed. The widening of old city roads such as Chang’an Avenue and Jingshan Front Street and the construction of ring roads have reduced the control of the central roads’ grid structure. The damage of symbolic landscapes and historical water systems also impaired the central axis’s functionality, continuity, and integrity [

50].

3.6. Evolution of Central Axis since 1976

Since 1976, the extension of the central axis has been mainly driven by remarkable events in the new era such as the Asian Games, the Olympic Games, and Beijing Daxing International Airport’s construction. Based on the central axis after the founding of the People’s Republic of China, it has been extended to Beijing Nanyuan Airport in the south and the Olympic Park in the north, and the total length is about 30.1 km, divided into five sections (

Figure 8). The widening of east-west roads such as Ping’an Avenue, Chang’an Avenue and Liangguang Road reduced the north-south axis’s influence, and the new large-scale public buildings on the axis further destroyed the initial spatial order of the axis and weakened the control of the central axis.

3.7. Summary of Development of Central Axis of Beijing and Prospects

A review of the development of the Central Axis of Beijing reveals that the formation of the initial city axis was mainly based on the city’s planning, characterized by a symmetrical and rigorous spatial sequence. The imperial power and ritual system confined its construction, and its fundamental purpose was to strengthen the feudal regime. With the abolition of the old feudal system, the connotation and meaning of the central axis have also changed. It is no longer a symbol of imperial power but has been given the significance of historical and cultural heritage. Its rigorous spatial sequence combination has become a lively urban characteristic. At the same time, with the development of the times, the core influencing factors of the central axis evolution have also developed from natural dominance to man-driven, from passive transformation to active construction, and from single factor action to multi-factor coupling interaction. In modern times, the influence of traditional natural elements has gradually reduced in the central axis’s evolution. While cities have adopted extensive development methods for land expansion and the extension of the central axis, they have often neglected natural elements such as the macro landscape pattern. In summary, the extension and development of the Central Axis of Beijing in the new era should focus on history and look to the future. On the one hand, it is necessary to study the guidance of the traditional factors, such as water system, greening, politics, traffic, etc., in the formation of the central axis pattern. On the other hand, we should judge Beijing’s future development trend and accurately obtain the possibility and development conditions of the extension of the central axis.

4. The Central Axis and Beijing’s Macro Landscape Pattern

The site selection of the ancient city of Beijing fully considers the regional mountains and rivers. It is located in the macro landscape pattern of Taihang Mountains, Yanshan Mountains and Yongding River. From Jichengof the Shang and Zhou dynasties, to Nanjing of the Liao Dynasty, Zhongdu of the Jin Dynasty, Dadu of the Yuan Dynasty, Beijing City of the Ming and Qing Dynasties, and then to Beijing in modern times, Beijing constantly built water conservancy projects to meet the needs of urban development (

Figure 9). For thousands of years, the Central Axis of has been inextricably linked with urban development and water system changes.

The prehistoric “Yanshan movement” and the invasion and retreat of sea water formed “Beijing bay”, which established the basic landscape pattern of Beijing with mountains on three sides and five rivers flowing through and opening to the southeast. Therefore, ancient Beijing has become an ideal geomantic treasure land for the urban location. From the Shang and Zhou dynasties to the Sui and Tang Dynasties (c.16th century–907), Jicheng was the political, economic and cultural center of the Beijing area. During the development of Jicheng, the water system inside and around the city underwent a series of changes. During the Three Kingdoms (220–280), the construction of Liling weir, the excavation of Chexiang canal, the increase of water channels and other water conservancy projects further enriched the regional water network system in Beijing, laying the foundation for the establishment of the later capital. During the Liao, Jin and Yuan dynasties (916–1368), capitals were built relying on water systems. In Liao Dynasty, “Nanjing” was established with Lianhuachi water system as the water source. In the Jin Dynasty, the city was expanded on the former site of Nanjing and the capital city was officially established. The Taining palace was established on the basis of Bailiantan water system in the northeast corner of the city, laying the foundation for the capital construction in the Yuan Dynasty. The capital city was moved to the Bailiantan water system with abundant water resources because of the water source problem in the Yuan Dynasty. The capital city was established on the basis of this water system. At the same time, a central pavilion was set up on the north side of the water system as the central point of the central axis. This not only formed the foundation of Beijing’s inner city water network system, but also laid the pattern of the traditional central axis. During the Ming and Qing Dynasties (1368–1911), the city of Beijing expanded southward. With the excavation of the moat and the connection of the inner and outer water systems, the water network system of Beijing’s old city of gradually formed. In modern times, driven by the construction of Nanyuan Airport and the holding of the Beijing Olympic Games, the traditional central axis further extended to the north and south, accompanied by the expansion of the water system. With the development of the city and the change of water supply demand, modern Beijing gradually changed the single water supply mode in the Ming and Qing dynasties. Yongding River diversion canal, Jingmi diversion canal and the South-to-North Water Diversion Project have been built step by step to realize water resources transfer in a larger area. The landscape pattern constitutes the natural and cultural background of the Central Axis of Beijing. The extension of the axis should fully consider the macro landscape system of Beijing.

5. Central Axis Governance: Property Rights Arrangement and Public Opinion Analysis

5.1. Housing Property Rights Form and Governance Model of Central Axis of Beijing

Since entering the new millennium, the Beijing government has paid much attention to the governance of the Central Axis of Beijing. The hosting of Beijing Olympic Games, the construction of Beijing Daxing International Airport, the renovation of shantytowns on the central axis and the declaration of the Central Axis of Beijing for world heritage have promoted the renovation of the central axis (

Figure 10).

In its historical evolution, the central axis area has formed a complex form of housing property rights. In the process of governance, relevant government departments put forward different governance strategies and implementation paths in line with different forms of property rights. From the perspective of land ownership, the land in the central axis area has two forms: state ownership and people’s collective ownership. From the perspective of housing ownership, there are three forms: public housing, private housing and collective property housing. Public housing can also be divided into public housing directly managed by the state or by the city government. Private housing can be divided into urban private apartments and apartments through housing reform. In the process of vacating and renovating, it involves the change of the right to use the house. For public housing, the state or Beijing government generally directly have taken back the right to use it. At the same time, monetary compensation is made to users of the original houses. For private housing, the Beijing government generally adopts a housing levy and undertakes shantytown renovation. At the same time, according to the wishes of house owners, monetary compensation or relocation are made. For collective property housing, land expropriation or shantytowns reconstruction are generally adopted. At the same time, the original land owners and housing owners receive compensations for land acquisition and house demolition. The developers also cooperate with the village collective for the unified construction and operation of the land. Let villagers participate in the profit and share the development dividend. From the perspective of governance, the governance model of the central axis has developed from the government-led model in the early years to the enterprise-led model now (

Table 1).

5.2. Public Opinion Analysis on Central Axis Governance

The paper uses big data to investigate the public opinion of the Central Axis of Beijing related governance work. First, the paper collects relevant content and public opinions of 1880 articles from 16 websites including Weibo, NetEase News, Tencent News, Sohu News and Sina News by using web crawlers with the keyword of “the Central Axis of Beijing and renovation”, and uses Rostcm6.0 (2) to undertake sentiment analysis on those texts. It was found that 63% of Chinese public opinion were neutral, 17% were positive and 20% were negative. It can be seen that the public has a certain degree of negative evaluation of the governance model of the Central Axis of Beijing.

The paper also takes four typical projects as keywords, namely “renovation of Bell and Drum Tower Square”, “renovation of shantytowns in Nanyuan village”, “renovation of shantytowns in Qingyundian town” and “renovation of Guanyinsi area in Dashilan” to conduct data collecting and text sentiment analysis. The results show social public opinions vary in different governance projects in the central axis area. In the early years, government-led governance projects such as “renovation of Bell and Drum Tower Square”, “renovation of shantytowns in Nanyuan village” and “renovation of shantytowns in Qingyundian town” received more negative social evaluations. In recent years, the governance mechanism of the central axis has been innovated. For example, projects such as “housing vacating of Guanyinsi area in Dashilan” have taken enterprise governance as the main body of implementation and fully investigated the wishes of residents. This innovative mechanism has gained more positive social evaluation (

Figure 11).

6. Current Situation and Problems of the Central Axis Extension Areas

At present, the length of the central axis will be extended from 30.1 km to 88.8 km. The area affected by the North–South extension of the central axis is 405.08 km

2. The land involved includes: rural land, agriculture, forestry, industry, water area, road traffic, etc. (

Table 2). There are some historical and cultural relics, and there are also some villages in the central axis extension areas. The existing road system is not systematic. The central axis extension areas involve 112 village settlements and 38 industrial areas, involving a population of about 740,000.

At present, the development of the Beijing central axis of and North–South extension line is facing a series of problems and challenges as follows:

First, Beijing’s new version of the master plan stipulates the start and endpoints of the extension of the central axis but does not clarify issues such as delineating the specific extension line control scope and the particular extension direction.

Second, the central axis area’s existing spatial control is mainly based on the longitudinal segmentation, and the land and buildings on both sides of it have not been effectively controlled. The style and features within a certain scope on both sides of the central axis have not been reasonably managed and preserved.

Third, compared with the traditional central axis area in Beijing, the central axis’s extension line area’s spatial organization is relatively blank. Its spatial sequence and functional positioning of different regions have not yet been formed.

Fourth, the traffic and urban grid in the central axis’s extension line area has not effectively coordinated with the traditional central axis of Beijing. On the one hand, the central axis and its extension line have been divided by ring roads; on the other hand, the north-south traffic on the central axis’s vertical extension line has not been essentially coordinated with the central axis.

Fifth, the water system in the central axis’s extension line area has not been effectively coordinated with the historical water system and the central axis. The water system’s organization in the area of the north–south extension line should fully consider the landscape pattern formed by the Central Axis of Beijing and its changes, as well as the spatial relationship between the water system and the central axis.

Sixth, the green space and ecological leisure system in the central axis’s extension line area have not been effectively coordinated with the central axis. On the one hand, they have not made full use of the green resources to form green corridors. On the other hand, the green space resources in the extension line area did not organically contact with the water system in the place and the cultural belt around the place.

Seventh, the context of the central axis and the north-south extension line area lacks systematic organization. On the one hand, the excavation and protection of historical relics and cultural resources of the extension line area have not been effectively carried out. On the other hand, the protection of historical relics and the development of cultural resources in the extension line area have not been effectively coordinated with the central axis.

Eighth, the sustainable governance system of the central axis. Housing vacating in the central axis area are related to the fundamental interests of residents, and there are many stakeholders affected, so it is necessary to establish a sustainable governance system with multi-party participation.

In order to achieve the benign development of the central axis and its extension line area in the future, it is necessary to carry out the corresponding planning and control according to current problems.

7. Overall Positioning of Central Axis of Beijing in New Era

The central axis is an essential context of Beijing’s development, and its extension and spatial layout along the central axis affect the direction of Beijing’s future innovation and growth. In the new historical period, the central axis should adhere to its unique political and cultural connotation, and be endowed with new significance, building it into the axis of metropolitan image, culture, people’s livelihood, and ecology.

7.1. Axis of Metropolitan Image

Political factors influenced the capitals’ planning and construction in the feudal society of ancient China. The formation of the axis was integrated with the will of emperors, and its strict sequence became a symbol of imperial power and a tool to consolidate the regime. In modern times, the Central Axis of Beijing’s grand spatial sequence shows China’s specific urban style and image. The future development of the central axis aims to highlight the metropolitan image of Beijing through the control of the overall style and features and the organization of the spatial sequence.

7.2. Axis of Culture

The central axis has witnessed the development of Beijing and has been endowed with vital cultural attributes. As a typical living heritage, Beijing City has condensed rich cultural connotations in the process of its growth, accumulation, and formation. As a crucial part of its evolution, the Central Axis of Beijing has played an important role in the cultural inheritance. In the new era, the Central Axis of Beijing will extend the urban context to the future in a new form.

7.3. Axis of People’s Livelihood

As the backbone of urban development, the central axis guides the urban spatial order and influences urban construction. The extension and development of the central axis should focus on people’s livelihood and strengthen the residential environment in the region. By integrating the area’s surrounding land and adjusting the functional positioning, the central axis’s overall vitality is enhanced, and the improvement of people’s livelihood is driven by the extension of the axis.

7.4. Axis of Ecology

In recent years, Beijing has strived to build a world-class ecologically livable city. As the city’s development axis, the central axis should be served as the leading area of planning concepts to achieve the city’s development positioning and goals. In the extension and development of the central axis, the organization of the regional rivers and lakes and the green space system should be reinforced, and the blue network and green corridors of the central axis should be remodeled based on the urban macro landscape pattern.

8. Planning and Control on Central Axis of Beijing’s Extension

Based on an in-depth analysis of the historical evolution of the Central Axis of Beijing, the relationship between the central axis and Beijing’s macro landscape pattern and its changes, as well as the governance pattern and public opinion of the community in the central axis area, the paper puts forward nine management and control strategies, including the control scope, extension direction, horizontal space control, axial space control, traffic system control, water system control, green space and ecological leisure system, context control, as well as sustainable governance mechanism.

8.1. Delimitation of Control and Management Scope of Central Axis and Its Extension Line

This study’s central axis continues to extend north and south based on the original section from the Olympic Forest Park to Beijing Nanyuan Airport, with a total length of about 88.8 km. The area spans the north, middle, and south of Beijing, covering an area of about 480 km

2, including seven administrative regions such as Changping, Daxing, Haidian, and Chaoyang districts, involving 54 towns, streets and regions (the southeast includes parts of Langfang) (

Figure 12).

When determining the north-south scope of the control area, this research referred to the central axis’s urban design scope in the Urban Design Scheme of the Central Axis of Beijing carried out in 2002 to achieve effective connection with previous related work. The north-central axis’s extension line starts from the north of the Olympic Forest Park in the south (Qinghe Road, Qinglin Road, Hongjunying South Road) to Yanshan Mountains in the north. The south-central axis’s extension line starts from the South 5th Ring Road in the north, and Beijing Daxing International Airport in the south with Shicui road in the south of the airport as the research boundary. When determining the east–west scope of the control area, on the one hand, we should respect the texture of natural features such as rivers and mountains, and the current situation of roads, railways, and transportation facilities. For example, when defining the extension line of the southcentral axis, consider the more important Beijing–Taipei Expressway and Beijing–Kowloon Railway in the area. On the other hand, we should fully consider the integrity of functional regions or affected areas that are of great significance to economic development and ecological protection in the areas of the central axis and its extension line. For example, when determining the north-central axis’s extension line, Litang Road has divided the Tiantongyuan community into two. Considering that Tiantongyuan, as a large-scale residential area, plays an important role in regional functions, its integrity should be maintained, so it should be all included in the research scope. The requirements of the overall research area of the central axis should also be considered, and the east–west width should be adjusted appropriately according to the research needs of different sections.

8.2. Control and Management Strategy of Central Axis’s Extension Direction

It is a fact that the Central Axis of Beijing deviates from the meridian. Some scholars have studied the difference between ancient and modern measurement techniques and geological changes caused by pole motion, precession, and nutation. Nonetheless, the results are not enough to prove the phenomenon of the central axis’s deviation [

51]. From the perspective of architectural geomantic omens, some current viewpoints believe that people deliberately carried out the deviation of the central axis in the Yuan Dynasty to grab auspicious positions. The direction of the deviation points to Shangdu of the Yuan Dynasty, the place of origin for Kublai Khan, the founder of the Yuan Dynasty [

52]. However, this view is controversial. Whether it was deliberate or coincidental by the ancients, the deflection angle has become a fact. Its influence on the future development of the central axis should be fully considered.

The Central Axis of Beijing is not a mechanical line. It encompasses the will of ancient rulers, the skills of city builders and the imprint of urban culture in its formation and development. Its significance has enlarged from physical remains to cultural symbols, including society and history. Looking back at the extension of the Central Axis of Beijing in modern times, no matter the construction of Beijing Nanyuan Airport or the Olympic Forest Park, drifting about two degrees from southeast to northwest has been maintained. It can be seen that respect for the central axis’s history is far more important than the beauty of the pure spatial design. We cannot fully understand the measuring technology used by the ancients when designing the central axis and the geomantic omen concept considered. Therefore, we should respect the history and retain its original form and cultural core. The extension and development of the axis in the future is a collision of history, culture, humanistic spirit, and design skills, so people should not limit the focus to the north and south of the geographical position. At present, the declination angle of Beijing’s north-south axis is a reality and is the result of historical precipitation. Therefore, this research should respect the history and explore the control strategy of the north–south extension of the Central Axis of Beijing with facts of the deflection angle.

8.3. Control and Management Strategy of Central Axis’s Horizontal Space

The central axis area’s spatial control is mainly based on vertical sections, namely the south-central axis section, the north-central axis section, and the traditional central axis section of the old city. After the central axis is extended, the area of the central axis’s extension line is also included in the control scope of the longitudinal segments. However, the lack of study and definition of the central axis’s horizontal space control scope has resulted in the fact that the style within a certain scope on both sides of the central axis has not been reasonably controlled and protected.

The “line” in the central axis includes the physical remains of buildings and structures, as well as invisible elements such as historical culture and place spirit and so on, which are spatially distributed on both sides. Therefore, in the planning and study of the extension line of the central axis, the “line”, a virtual boundary with only position and no scope, should be expanded into a plane, and a specific control scope should be defined, which will guide the development and protection of the area.

The research team tried to delimit the horizontal space control scope of the central axis’s extension line. We proposed dividing the space horizontally into core area, sub-area, and radiation area (

Figure 13). The core area is centered on the extension line of the Yongding Gate- Bell and Drum Tower, with an extension of 800 m on both sides. The core area’s management and control requirements should be based on each district’s development positioning vertically, combined with the central axis’s development elements, and implement differentiated management and control requirements. The north-central axis’s core area should implement its functional positioning for international exchange, sports, and culture. The south-central axis’s core area should implement its functional positioning as a new engine for promoting the southern city. The traditional central axis’s core area should be strictly protected while the horizontal space’s management and control should be implemented to achieve horizontal and vertical control.

The scope of the sub-area is based on the boundaries on both sides of the central axis’s core area, extending 1.6 km respectively in the east–west direction. The focus of sub-area management and control is mainly on the transition between the axis space and the non-axis space with protection and development as the leading management and control requirements. The radiation area refers to the place that extends outward based on the boundaries on both sides of the sub-area with no specific limited scope, and ecological control is the main focus.

8.4. Control and Management Strategy of Central Axis’s Axial Space

The central axis is vital to Beijing’s spatial organization. Based on the current resources and planning prospects of the central axis’s different areas, this study proposes management and control requirements of the central axis’s axial space and finally implements the overall positioning (

Figure 14).

The area from Ansi Road to North 6th Ring Road relies on the Xiaotangshan Hot Spring Resort to create the axis of ecological vacation, leisure, and wellness. The area from North 6th Ring Road to Huinan Road relies on Beiqing Road’s cutting-edge technological development to create the axis of scientific and technological innovation in the new era. The area from Huinan Road to the Olympic Forest Park relies on the Taiping Suburb Park, the Dongxiaokou Forest Park, Banjie Tower, Niangniang Temple and other ecological and cultural resources. Itfocus on constructing the forest park of the north-central axis to create the axis of ecological and cultural. The area of the north-central axis from the Olympic Forest Park to the North 2nd Ring Road takes the Asian Games and the Beijing Olympic Games as an opportunity to combine modern sports culture with the central axis to create the axis of leisure and international communication. The central axis of the old city from the North 2nd Ring Road to Yongding Gate combines existing cultural resources and continues the historical context to forge the axis of the image of global power, and the axis of culture and people’s livelihood. The area of the south-central axis from Yongding Gate to South 5th Ring Road and the area between the South 5th Ring Road to South 6th Ring Road rely on cultural and ecological resources such as the Liangshui River, Beijing Camping Park, Taoyuan Park, Nanyuan Park, and Nanhaizi Park. Combining the Nanyuan Park as the first royal garden in the Qing Dynasty and the relocation of the Beijing Nanyuan Airport to build the forest park of the south-central axis and create the axis of ecology and leisure. The area from South 6th Ring Road to Xiaolong River relies on the strategic advantages of the southern high-tech manufacturing and strategic emerging industry development belts, and the town’s ongoing work of “remediation and improvement” to create the axis of technological innovation. The area from Xiaolong River to Shicui Road relies on Beijing Daxing International Airport, and its functional layout should be improved to achieve a good connection with the new airport, simultaneously combining the Dalong River, Xiaolong River, Xintiantang River and other water systems to create the axis of ecology and leisure.

According to the characteristics of different areas of the central axis, the divisional spatial organization and functional positioning are carried out. The overall strategic positioning of the axis of the metropolitan image, culture, people’s livelihood, and ecology will be finally implemented.

8.5. Control and Management Strategy of Central Axis’s Traffic

The current roads in the area of the traditional central axis are mainly a grid system composed of the 5th Ring Road and its arterial and secondary trunk roads. The area of the north-south extension line connects multiple horizontal roads based on the southcentral axis road, the new Airport Expressway and the Litang Road. Its road network density is low, and there is no grid system.

This study proposes to organize the road network, rail transit and slow traffic with the central axis as the core for the regional traffic’s control and management strategy (

Figure 15). First, the road network in the central axis area should be extended northward and southward, and the road network density in the north–south extension area should be increased to establish a road grid system. The Beijing-Tongliao Railway, the Beijing-Baotou Railway, the Beijing-Shanhaiguan Railway, and Huangxu Highway in the region split the longitudinal traffic in the central axis area. The impact of external traffic facilities on the vertical road network should be minimized to ensure the road network’s continuity. Transformand construct existing or future railways and highways by crossing the area into the ground or overhead. Secondly, rail transit has an irreplaceable role in connecting functional areas and easing people’s flow in megalopolis. The research should consider setting up rail transit stations based on important nodes in the central axis and extending rail transit lines vertically, such as extending Beijing subway Line 5 in the north and the subway Line 8 in the south along Litang Road, and increasing the density of rail transit. This will connect the functional areas along the central axis as a whole through rail transit. Finally, slow roads can strengthen the central axis’s existence. At present, the slow lane traffic system in the area of the Central Axis of Beijing is not perfect, and there are problems such as fragmentation of slow-moving traffic by large buildings. This study attempts to restore slow lanes in some sections, and organize the slow lane traffic system in the area of the north-south extension line. According to the zoning in the spatial management and control strategy mentioned above, the sub-areas on both sides should continue slow lane traffic to ensure the traffic system’s continuity in the central axis and its north–south extension line. At the same time, important public spaces on the axis should establish slow-moving nodes to enhance the observers’ experience on the axis.

8.6. Control and Management Strategy of Water System of Central Axis

The central axis has complex connotations, and its evolution is closely related to Beijing’s macroscopic landscape. The extension of the central axis is often accompanied by the water system’s changes, and urban areas are also spatially connected through dense river networks. Through the investigation and analysis of three major river systems (Wenyu River system, Chaobai River system, and Yongding River system) and 15 major rivers within the area of the central axis, we found that the water networks density is relatively large and the water networks systems have become a scale in the current area of the traditional central axis. The water networks are mostly east–west and lack insufficient vertical connections and the systems of the water networks lack effective management in the area of the central axis’s extension line.

Based on this, given the disappearance of microscopic water systems such as Longxu Ditch, Jinyu Pond, and the east, west, south moats of the outer city filled as underground rivers, the study considers combining the traditional river channels and restoring the original water system, forming a water network sequence that echoes the central axis. On the one hand, slow walking trails should be set up along rivers to form riverside ecological parks; on the other hand, the existing water system should be combined with historical context to create a cultural corridor along rivers. There are three crucial water systems, namely, the Jingmi Diversion Canal, Wenyu River, and Qinghe River, and two tributaries of Xiaocun River and Hulu River in the area of the north-central axis’s extension line. The water networks are well developed. The planning should consider relying on the three major water systems in the region to explore historical context and cultural connotation, and creating a space of vitality by selecting nodes that connect with the water systems on the axis. Simultaneously, the planning should improve the landscape along the Xiaocun River and Hulu River and use the existing hot spring palace culture to build the northern hot spring cultural industry cluster and promote the development of surrounding areas. The area of the southcentral axis’s extension line relies on the Xinfeng River, Dalong River, Xiaolong River, Xintiantang River, and other water systems and cultural resources of Nanyuanto organize the water system. Based on the north–south flow direction of the Xiaolong River, it is considered to combine the central axis to create a characteristic linear area. The characteristic water area at the confluence of the Dalong River will create the landscape node and vitality center. Also, the Xintiantang River, as a landmark landscape at the gateway of the new airport, can be combined with the construction of the new airport to create a riverfront science and cultural park or a recreational park (

Figure 16).

8.7. Control and Management Strategy of Central Axis’s Green Space and Ecological Leisure System

As an ecological corridor connecting urban landscape green spaces, the central axis has an important impact on the development of urban green spaces and environmental leisure systems. There are 28 green parks and three forest parks in the study area. They have problems such as uneven spatial distribution and a weak sense of the linear sequence of green space combined with axis arrangement.

At present, the construction of the first green partition in the traditional central axis has been basically completed. The central axis’s north-south extension line area is located between the nine wedge-shaped green spaces proposed in the new version of the Beijing master plan and the ongoing second green partition, and its green space construction needs to be further improved. The study suggests that the future green space planning and construction in the central axis area should base on the planning of the two green isolation belts, optimize the layout of parks’ green lands in the area along the line and the combination with the central axis. The area of the traditional central axis should be combined with the existing green ecological landscape system to create a characteristic green space layout. Part of green lands should be rebuilt and expanded to create a more comfortable living space. The possibility of comprehensively building a heritage park should be considered. The current area of the north-central axis’s extension line has more green areas in the south than north, and lacks important nodes. The planning should combine the two green partitions and wedge-shaped greens place, integrate the existing park green space, and consider expanding the existing green space. The water front green belts of the three important water systems are used as the regional core landscape node to enhance the central axis and their axial sequence. The area of the south-central axis’s extension line has a small amount of green space and scattered layout. The planning should consider combining the important landscape nodes, such as Tuanhe Palace Relic Park and Banbidian National Forest Park, and joint characteristic industrial bases to optimize the landscape and strengthen connection with water systems. The radiation area of Tuanhe Palace on the north side is combined with the ecological resources of the Nanyuan area to create a forest park of the south-central axis corresponding to the north one. Riverside parks and regional suburb parks should be built according to the current water system and green space. Other scattered micro green spaces should expand their spatial scope within the allowable land use and realize the organic combination of flaky green space and dotted green space in the area (

Figure 17).

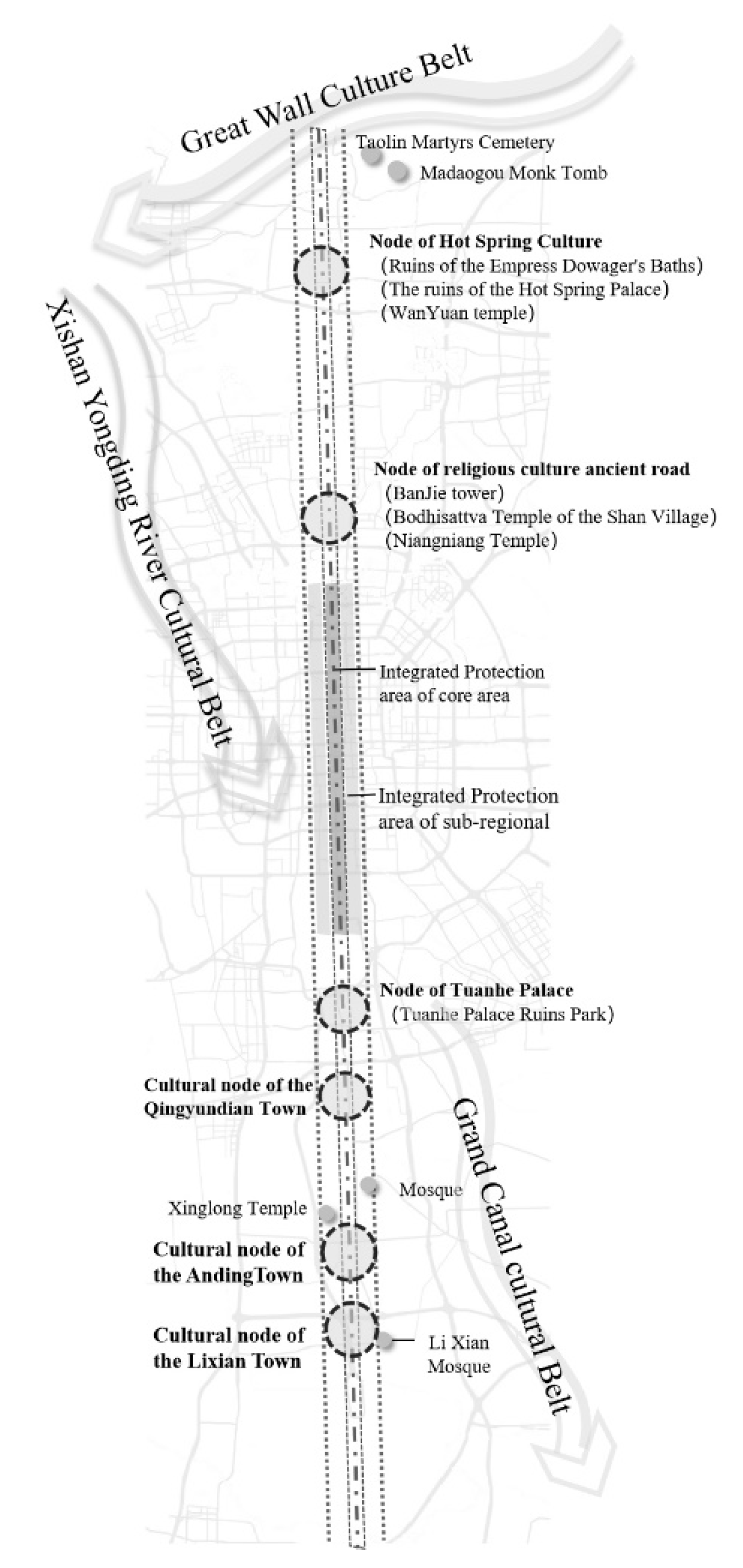

8.8. Control and Management Strategy of Central Axis’s Context

Given the control and management strategy of the central axis’s context, we should grasp the status quo of traditional houses, historical resources, and important historical junctions within the region, and study the methods of historical and cultural inheritance and resource protection in areas along the central axis (

Figure 18).

The historical and cultural resources of the area of the traditional central axis are vibrant. In particular, there are 33 historical and cultural protection districts in the old city, most of which are distributed in the core area (20 districts) and sub-area (11 districts) of the central axis. The planning should study the feasibility of designating the overall protection and control area. It is necessary to strengthen the renewal and protection of the existing traditional residential and commercial districts, demolish some large public buildings that affect its artistic style, retain the attributes of “habitation” and “culture”, and reflect the features of the axis of people’s livelihood and culture. Moreover, we should also consider repairing and rebuilding important buildings and structures on the central axis such as the imperial city walls and gates to continue the heritage of the area.

The area of the north-central axis’s extension line relies on Jundu Mountain, Yanshan Mountains, and the three vital water systems in the macroscopic view. It is adjacent to the Great Wall cultural belt on the north side and the Xishan-Yongding River cultural belt on the west side. First of all, we should explore its cultural connotation to create a characteristic cultural landscape area. Secondly, the connection and response between the six historical and cultural relics within the site and the surrounding cultural belts should be considered so as to make functional connections and accelerate the spread of the regional culture. In the central area where historical relics are relatively concentrated, combined with the hot spring palace ruins, we should create a characteristic hot spring cultural area. In the south area, we should rely on historical relics (Niangniang Temple and Banjie Tower) to form a religious and cultural road.

The area of the south-central axis’s extension line is adjacent to the Grand Canal cultural belt on the east side. There are four historical and cultural relics, and three historical towns and villages within the area. However, its existing cultural resources have not formed a cultural node and the shaping of its cultural node should be strengthened. Taking the Tuanhe Palace as an example, on the one hand, the development and construction activities around its current remains should be managed and controlled to fully protect its historical features. On the other hand, we should strengthen the cultural inheritance of the Tuanhe Palace, and further build its tourist area combined with the water system. At the same time, relying on the three important historic and cultural towns of Anding Town, Lixian Town and Qingyundian Town, we should create important historical and cultural nodes in the area and form an organic connection with the Grand Canal cultural belt in general.

8.9. Establishing a Sustainable Governance Mechanism of Central Axis Based on Property Rights

At present, the central axis area has formed a set of governance mechanisms including housing vacating, repair and management, environmental renovation, residents’ resettlement compensation and so on. Through the analysis of public opinion of central axis governance based on big data, we find that there are more negative public opinions in the government-led governance model. In the process of governance, there are still some problems such as insufficient consideration of opinions of the local community and insufficient coordination of the interests of multiple stakeholders.

Therefore, it is necessary to set up a sustainable governance mechanism of the central axis based on property rights. First, it is necessary to fully protect the interests of land and housing ownership and the right holders. It is suggested that the value of land and housing should be evaluated independently by a third party. Second, based on the market mechanism, the transfer system of property rights (development rights) should be established. Third, we should give full consideration to the wishes of the residents. Fourth, we should establish the multi-subject coordination mechanism, including property owners, relevant government departments, communities, the public, developers and other multiple stakeholders. Fifth, the public sector should fully protect public interests. Sixth, we should establish the appeal arbitration mechanism for the central axis governance.

9. Conclusions and Research Prospects

The Central Axis of Beijing is not only the carrier of Beijing’s history and culture, but also the core element of its spatial order. The Beijing government has decided to extend the central axis southward and northward, ushering in new opportunities for its protection and development and cultural inheritance. The large extension of the central axis this time will profoundly affect its overall structure and function. Based on the HUL analysis framework, the paper constructs an overall analysis framework including the historical evolution of the central axis, the relationship between the central axis and Beijing’s macro landscape pattern and its changes, the relationship between the central axis and urban elements such as land utilization, transportation, water system, green space and leisure system, and the property rights arrangement and public opinion analysis in the central axis governance. Under the analysis framework above, the paper expands the overall positioning of the new central axis, and puts forward the overall control strategy system of it on the basis of comprehensive historical and cultural heritage, natural ecological elements and urban elements. First of all, the paper puts forward the overall positioning which is different from the traditional central axis. That is to say, the overall positioning of Beijing’s new central axis is expanded from the traditional cultural axis to the axis of culture, city image, people’s livelihood and ecology. Second, the paper puts forward the overall management and control system of the new central axis, which includes nine aspects: control scope, extension direction, horizontal space, axial space, traffic system, water system, green space and leisure system, context protection and governance system.

In addition, there are still many deficiencies in this paper, which need to be further studied. First, the paper emphasizes the historical evolution of the Central Axis of Beijing, the relationship between the central axis and Beijing’s macro landscape pattern, and the integration of the central axis and urban elements, which weakens the evaluation of the value of historical and cultural relics and intangible cultural relics on the micro level. The follow-up research needs to strengthen these researches at the micro level, so as to enrich the overall analysis framework of the Central Axis of Beijing and the overall control strategy system of the North–South extension of it. Second, the research on property rights and the governance mechanism of central axis needs to be further deepened. At present, the paper uses the public opinion analysis based on big data to conclude that the market-oriented governance model of the central axis has higher efficiency and public satisfaction than the government-led governance model. It also proposes to establish a sustainable governance mechanism of the central axis based on property rights. However, it is a challenge to build a system and mechanism for the protection and development of the Central Axis of Beijing with public participation and multi-stakeholder coordination, which needs further study.