What Matters for Job Security? Exploring the Relationships among Symbolic, Instrumental Images, and Attractiveness for Corporations in South Korea

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Symbolic, Instrumental Images, and Attractiveness Toward the Organization

2.2. Hypotheses

3. Research Method

3.1. Sampling

3.2. Analytical Method and Measure

3.2.1. Analytical Method

3.2.2. Measure

Instrumental Images

Symbolic Images

Attractiveness Toward an Organization

4. Analyses Results

4.1. Study 1 Findings

4.1.1. Preliminary Findings

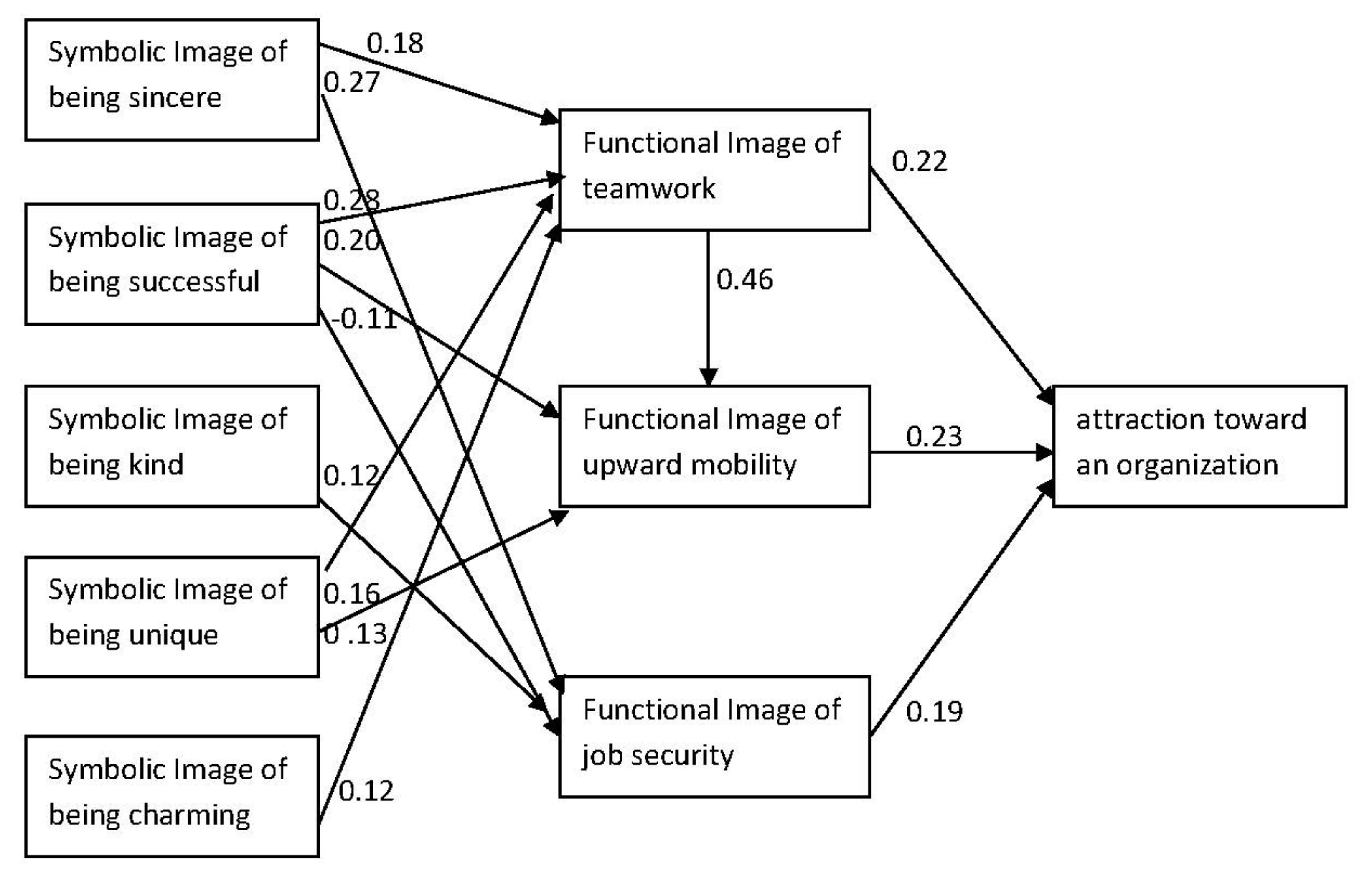

4.1.2. Main Findings

4.2. Study 2 Findings

4.2.1. Preliminary Findings

4.2.2. Main Findings

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Implications

6. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rynes, S.L.; Cable, D.M. Recruitment research in the twenty-first century. In Handbook of Psychology: Industrial and Organizational Psychology; Borman, W.C., Ilgen, D.R., Klimoski, R.J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; Volume 12, pp. 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hoye, G.; Bas, T.; Cromheecke, S.; Lievens, F. The instrumental and symbolic dimensions of organisations’ image as an employer: A large-scale field study on employer branding in Turkey. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 62, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissel, P.; Büttgen, M.J. Using social media to communicate employer brand identity: The impact on corporate image and employer attractiveness. J. Brand Manag. 2015, 22, 755–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlander, G.W.; Snell, S.A. Principles of Human Resource Management, 16th ed.; Thomson South-Western, Cengage Learning: Mason, OH, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lukaszewski, K.M.; Dickter, D.N.; Lyons, B.D. Recruitment and selection in and Internet context. In Human Resource Information Systems: Basics, Applications, and Future Directions, 4th ed.; Kavanagh, M.J., Johnson, R.D., Eds.; SAGE: Los Angeles, LA, USA, 2018; pp. 257–288. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, C.J.; Stevens, C.K. The relationship between early recruitment related activities and the application decisions of new labor-market entrants: A brand equity approach to recruitment. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 1121–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slaughter, J.E.; Stanton, J.M.; Mohr, D.C.; Schoel, W.A., III. The interaction of attraction and selection: Implications for college recruitment and Schneider’s ASA model. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2005, 54, 419–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highhouse, S.; Zickar, M.J.; Thorsteinson, T.J.; Stierwalt, S.L.; Slaughter, J.E. Assessing company employment image: An example in the fast-food industry. Pers. Psychol. 1999, 52, 151–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lievens, F.; Decaesteker, C.; Coetsier, P.; Geirnaert, J. Organizational attractiveness for prospective applicants: A person–organization fit perspective. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2001, 50, 30–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lievens, F.; Highhouse, S. The relation of instrumental and symbolic attributes to a company’s attractiveness as an employer. Pers. Psychol. 2003, 56, 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, S.; Ozer, G. The analysis of antecedents of customer loyalty in the Turkish mobile telecommunication market. Eur. J. Mark. 2005, 39, 910–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, M.H.; Pan, S.L.; Setiono, R. Product-, corporate- and country-image dimensions and purchase behavior: A multicounty analysis. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2004, 32, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.; Chung, T. Relationships among attitude, corporate image, and purchase behavior in Korean running event. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2018, 10, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- David, P.; Kline, S.; Dai, Y. Corporate social responsibility practices, corporate identity, and purchase intention: A dual process model. J. Publ. Relat. Res. 2005, 17, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, D.H. Consumer perception of corporate donations. J. Advert. 2003, 32, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, D.; Coelho, P.S.; Vilares, M.J. Service personalization and loyalty. J. Serv. Mark. 2006, 20, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bloemer, J.; Ruyter, K. On the relationship between store images, store satisfaction and store loyalty. Eur. J. Mark. 1998, 32, 499–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.; Leblanc, G. Corporate image and corporate reputation in consumers’ retention decisions in services. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2001, 8, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y. Service quality, perceived value, corporate image, and customer loyalty in the context of varying levels of switching costs. Psychol. Market. 2010, 27, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim. S., Y. Jae-seok Yoo Joins a Good Shop ‘Paying for Money’ That Gave Free Chicken to His Brothers. Maeil Business News Korea. Available online: https://www.mk.co.kr/news/culture/view/2021/03/262423/ (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Kashive, N.; Khanna, V.T. Study of early recruitment activities and employer brand knowledge and its effect on organization attractiveness and firm performance. Global Bus. Rev. 2017, 18, S172–S190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lievens, F.; Van Hoye, G.; Schreurs, B. Examining the relationship between employer knowledge dimensions and organizational attractiveness: An application in a military context. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2005, 78, 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lievens, F.; Van Hoye, G.; Anseel, F. Organizational identity and employer image: Towards a unifying framework. Br. J. Manag. 2007, 18, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lievens, F. Employer branding in the Belgian Army: The importance of instrumental and symbolic beliefs for potential applicants, actual applicants, and military employees. Human Resour. Manag. 2007, 46, 51–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.Y.; Kim, Y.K. A development of tentative measuring items of Korean corporate symbolic image using brand personality. J. Korea Soc. Ind. Inf. Syst. 2012, 17, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Slaughter, J.E.; Zickar, M.J.; Highhouse, S.; Mohr, D.C. Personality trait inferences about organizations: Development of a measure and assessment of construct validity. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 89, 85–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Hoye, G.; Saks, A.M. The instrumental-symbolic framework: Organizational image and attractiveness of potential applicants and their companions at a job fair. Appl. Psychol. Int. Rev. 2011, 60, 311–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harold, C.M.; Ployhart, R.E. What do applicants want? Examining changes in attribute judgments over time. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2008, 81, 191–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodard, M.S.; Miller, J.K.; Miller, D.J.; Silvernail, K.D.; Guo, C.; Nair, S.; Marx, R. A cross-cultural examination of preferences for work attributes. J. Manag. Psychol. 2016, 31, 702–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lam, S.K.; Ahearne, M.; Schillewaert, N. A multinational examination of the symbolic–instrumental framework of consumer–brand identification. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2012, 43, 306–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aaker, J.L. Dimensions of brand personality. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 34, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreurs, B.; Druart, C.; Proost, K.; Witte, K.D. Symbolic attributes and organizational attractiveness: The moderating effects of applicant personality. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2009, 17, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korac, S.; Saliterer, I.; Weigand, B. Factors affecting the preference for public sector employment at the pre-entry level–A systematic review. Int. Publ. Manag. J. 2018, 22, 797–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentier, M.; Van Hoye, G.; Weijters, B. Attracting applicants through the organization’s social media page: Signaling employer brand personality. J. Voc. Behav. 2019, 115, 130326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Saini, G.K. Do instrumental and symbolic factors interact in influencing employer attractiveness and job pursuit intention? Career Develop. Int. 2018, 23, 444–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waples, C.J.; Brachle, B.J. Recruiting millennials: Exploring the impact of CSR involvement and pay signaling on organizational attractiveness. Corp. Soc. Resp. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 870–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. The Companies That Undergraduate Students Want to Work for the Most. Kyunghyang Newspaper. 2014. Available online: http://bizn.khan.co.kr/khan_art_view.html?artid=201409021452411&code=920507&med=khan (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Kim, C.K. The study of advertising strategy based on brand personality. Korean J. Advert. 1998, 9, 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, C.K.; Ahn, Y.H. The role of brand personality based on the FCB grid model. Korean J. Advert. 2000, 11, 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.K. The study of influencing factors and types of brand personality. Korean J. Advert. 2000, 49, 29–53. [Google Scholar]

- Highhouse, S.; Lievens, F.; Sinar, E.F. Measuring attraction to organizations. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2003, 63, 986–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Korea. Economically Active Population Survey in February 2018. Available online: http://kostat.go.kr/portal/eng/pressReleases/5/2/index.board?bmode=read&aSeq=366650&pageNo=4&rowNum=10&amSeq=&sTarget=title&sTxt= (accessed on 10 May 2020).

- Jang. Y., H. [General] Naver Rises to the No. 1 Company That College Students Most Want to Work for. Joongang Daily. Available online: http://news.joins.com/article/20276972 (accessed on 7 July 2016).

- Kim, S.S. JenniferSoft’s ‘Ideal Welfare Culture’. Available online: https://jennifersoft.com/en/news/2012-08-09/ (accessed on 9 August 2012).

- Is Jennifer Soft a Dream Company? Noone is Told What to Do, and Swimming is Regarded as Working Time. Available online: https://jennifersoft.com/en/news/2018-01-12/ (accessed on 12 January 2018).

- Oh, H.; Weitz, B.; Lim, J. Retail career attractiveness to college students: Connecting individual characteristics to the trade-off of job attributes. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 31, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.G.; Min, K.B.; Chang, S.J.; Kim, H.C.; Min, J.Y. Job stress and depressive symptoms among Korean employees: The effects of culture on work. Int. Ach. Occup. Environ. Health 2009, 82, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentier, M.; Van Hoye, G.; Stockman, S.; Schollaert, E.; Van Theemsche, B.; Jacobs, G. Recruiting nurses through social media: Effects on employer brand and attractiveness. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 2696–2708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Valuables | Index | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 20 to 24 years old | 7 | 2.19 |

| 25 to 30 years old | 71 | 22.26 | |

| 31 to 39 years old | 157 | 49.22 | |

| 40 to 49 years old | 78 | 24.45 | |

| 50 or older | 6 | 1.88 | |

| Education Level | High School graduates | 26 | 8.15 |

| Currently attending a 2-year college | 5 | 1.57 | |

| 2-year college graduates | 17 | 5.33 | |

| Currently attending a 4-year college | 14 | 4.39 | |

| 4-year college graduates | 194 | 60.50 | |

| Currently attending a graduate school | 5 | 1.57 | |

| Graduate degree holder | 59 | 18.50 | |

| Job Type | Sales/Marketing | 55 | 17.24 |

| Accounting/Finance | 11 | 3.45 | |

| HR/IR | 16 | 5.02 | |

| Institute of Technology | 42 | 13.17 | |

| Technical Support | 65 | 20.38 | |

| Customer Support | 62 | 19.44 | |

| Production | 5 | 1.57 | |

| Planning/Strategy | 40 | 12.54 | |

| Management Support/Secretary | 11 | 3.45 | |

| etc. | 12 | 3.76 | |

| Job Position | Staff | 74 | 23.20 |

| Chief | 18 | 5.64 | |

| An assistant manager | 108 | 33.86 | |

| A deputy general manager | 81 | 25.39 | |

| A department manager or higher | 38 | 11.81 | |

| Working years at the current organization | Less than 1 year | 31 | 9.72 |

| 1 to 3 years | 50 | 15.67 | |

| 4 to 6 years | 50 | 15.67 | |

| 7 to 9 years | 47 | 14.73 | |

| 10 or more years | 141 | 44.20 |

| Variables | χ2 | NFI | CFI | IFI | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1 | Instrumental images (three factors) | 451.17 | 0.94 | 0.95 | 0.95 | 0.062 |

| Symbolic images (five factors) | 781.51 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.057 | |

| Organizational attractiveness | 120.68 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.033 | |

| Study 2 | Instrumental images (three factors) | 253.48 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.077 |

| Symbolic images (five factors) | 4.84 | 0.95 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.070 | |

| Organizational attractiveness | 31.69 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.031 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oh, J.; Myeong, S. What Matters for Job Security? Exploring the Relationships among Symbolic, Instrumental Images, and Attractiveness for Corporations in South Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4854. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094854

Oh J, Myeong S. What Matters for Job Security? Exploring the Relationships among Symbolic, Instrumental Images, and Attractiveness for Corporations in South Korea. Sustainability. 2021; 13(9):4854. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094854

Chicago/Turabian StyleOh, Juyeon, and Seunghwan Myeong. 2021. "What Matters for Job Security? Exploring the Relationships among Symbolic, Instrumental Images, and Attractiveness for Corporations in South Korea" Sustainability 13, no. 9: 4854. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094854

APA StyleOh, J., & Myeong, S. (2021). What Matters for Job Security? Exploring the Relationships among Symbolic, Instrumental Images, and Attractiveness for Corporations in South Korea. Sustainability, 13(9), 4854. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094854