Economic Sustainability of Touristic Offer Funded by Public Initiatives in Spanish Rural Areas

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- -

- What is the sustainable rate of these aids?

- -

- Are there characteristics in the municipalities that determine their success?

- -

- What factors influence the economic sustainability of tourism businesses?

- -

- Is there a type of tourism business that is more successful?

- -

- Is the Leader period in which it was financed influencing the closure of businesses?

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

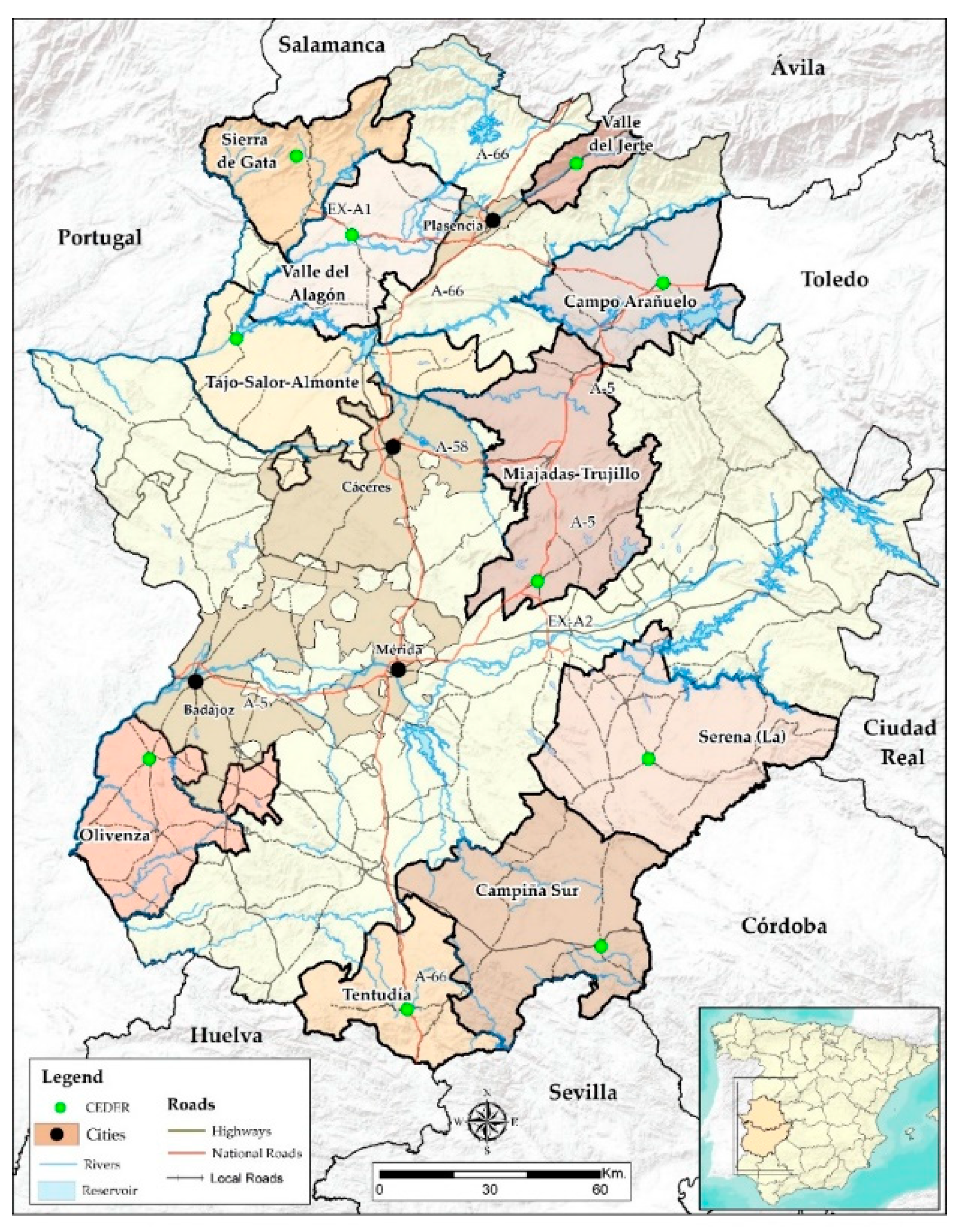

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Database

- -

- Hotel Accommodations: include accommodations classified as hotels, hostels, hotel-apartments, guesthouses and inns.

- -

- Rural Accommodations: rural houses, rural hotels and rural apartments.

- -

- Non-hotel Accommodations: hostels, camping sites and tourist apartments.

- -

- Catering Service: cafeterias, pubs and restaurants.

3.3. Data Analysis

Clustering Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Description of Data

4.2. Clustering Analysis

- -

- Group 1: it groups a total of 34 municipalities, 91.1% of them located in the province of Cáceres. It has a high percentage of projects and active financing, 80.6% and 91.5% on average, respectively. These 34 municipalities are the ones that have invested the most with an average of 959 euros per inhabitant and 11 projects per thousand inhabitants, because their population size is small (the average is 768 inhabitants, with 76.4% with less than 1000 inhabitants, and only 8.8% with more than 2000). In other words, these municipalities have managed significant economic resources in relation to the size of their population. On the contrary, they are municipalities with a high aging, an old age index of 33.1 and an economic income similar to the average (10,000 euros). These municipalities are mainly located in mountainous areas or in the peneplain; in areas with poor soils that have hindered the development of a productive agricultural sector related to irrigation or vineyards and olive groves, as in the most dynamic areas of the region. As for access to the highways, the average is 17 min, although there are differences between the nuclei of this group. On the one hand, there are the municipalities near the cities of Cáceres and Plasencia (main tourist destinations in the region) which have an access time to the highways of less than 15 min, and on the other hand, those located in the border areas of Portugal with a minimum time of 40 min. With regard to investments, the main investment has been in rural-type accommodation, 70%, with 62 establishments open, financed mainly in the last two periods. They are characterized by their high natural and scenic value, since most of them are located in mountain areas and have water resources. This group has a “High” success rate, as active projects exceed 80% and 91.5% of the investment made is still active. It should also be noted that 92% of private investment in the municipalities in this group is active. Although these investments in tourism are not being sufficiently decisive to curb the regressive demographic variables or to considerably increase their economic income.

- -

- Group 2: composed of 43 municipalities with an average population of 4000 inhabitants (they are large municipalities, some of them with more than 10,000 inhabitants, so their demographic losses are less pronounced than in the other groups), their old age index is the lowest, although their economic incomes are among the lowest in the region (less than 10,000 euros in many of them). It presents a success rate rated high—moderate, since the number of active projects is equal to those of group 1, but the active investment and average active private investment are lower, at 84.8 and 78.9% respectively, as well as the investment made per inhabitant, 176 euros. It is a group whose financing has been mainly destined to catering services and rural accommodation during the last two Leader periods. Two typologies can also be presented: those that have destined their investments fundamentally to the accommodations and that are developing a new infrastructure of rural tourism and that are located in the Valley of the Jerte; (main receiver of tourists only behind the 3 main cities of the region: Badajoz, Cáceres and Mérida and in the distance radius to Madrid of less than 2 h) and related to the natural resources of mountain and water; and in Tajo-Salor-Almonte and Miajadas-Trujillo where the proximity to the city of Cáceres (main tourist city of the region and receiver of travelers), as well as the existence of important cultural attractions such as the medieval city of Trujillo or the Museum and Natural Monument of Los Barruecos influencing the maintenance of their tourist businesses. On the other hand, in the LAGs located in the province of Badajoz, the resources financed by the catering sector, which in most cases are not focused on the development of the tourism sector, and the existence of some places with a high value on cultural resources, such as Olivenza or Tentudía, have been maintained. In addition, all the municipalities where the Rural Development Centers of all the LAGs are located appear, which shows that the location of the Rural Development Centers has a positive influence on the investments and maintenance in the nuclei where they are located in all the economic sectors.

- -

- Group 3: group formed by 35 municipalities, 60% in the province of Cáceres. This group has an average population of 1200 inhabitants, 60% of the municipalities have less than 1000 inhabitants and a high old age index close to 30. The loss of population is very pronounced in this group, with municipalities that have lost almost 50% of their population since 2000. Municipalities with a population of more than 2000 inhabitants have an economic activity linked to industry, granite quarries, or the irrigated agricultural sector. In terms of investment in tourism businesses, it is a group with an investment of 295 euros per inhabitant and the average number of projects is 4 per thousand inhabitants, so its indicators are not relatively far from the average, but being municipalities that have a small population size has not been sufficient to create an attractive offer in the places where they are located. In the case of this group, rural accommodations and catering services are the business categories with the largest number of active funded establishments with 18, although the most successful category is non-hotels establishments with 3 active establishments (75%). It is a group with a low survival success rate, with 20% of the active projects despite the fact that some of them are in ideal locations (mountain areas), due to their remoteness from the main urban centers of the region and from Madrid. In addition, although in terms of population, they have received funding and number of projects with optimal values and close to the average, having such a small population size, in the end they have focused on funding one or two projects per municipality and this does not generate enough synergies to attract tourists. They may present values similar to Group 1 with a high success rate in terms of location, natural resources or wealth, but they fail in the values of the number of projects and investments made. This group has been categorized as ″Low″.

- -

- Group 4: a total of 7 municipalities located in the province of Cáceres. Only one municipality exceeds 1000 inhabitants (Almaraz), the rest does not exceed 500 inhabitants. These are areas with high incomes (over 13,000 euros), the most dynamic demographic data of the 4 groups (lower population loss and old age index) and an economic sector linked to the industrial sector, which is why their incomes are higher and they have high unemployment rates in the service sector. This group, although showing a high average investment of 701 euros per inhabitant and an average of 5 projects per thousand, has not succeeded in making any of the funded establishments last. They are municipalities that do not have natural or cultural resources, their economic activity is linked to the proximity of nuclear or hydroelectric power plants and the establishments that have been funded have not survived because these municipalities have neither tradition nor tourist infrastructure complementary to those funded by Leader. This group was cataloged as “Unsuccessful” in Leader.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albaladejo Pina, I.P.; Díaz Delfa, M.T. Rural tourism demand by type of accommodation. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 951–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busby, G.; Rendle, S. The transition from tourism on farms to farm tourism. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, J. Farm accommodation and the communication mix. Tour. Manag. 1996, 17, 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppermann, M. Rural tourism in Southern Germany. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciolac, R. Tourism in European rural area-case study Austria. Agric. Manag. Lucr. Stiintifice Ser. I Manag. Agric. 2011, 13, 109–112. [Google Scholar]

- Cazes, G. Tourism in France. Tour. Fr. 1984, 128. [Google Scholar]

- Randelli, F.; Romei, P.; Tortora, M. An evolutionary approach to the study of rural tourism: The case of Tuscany. Land Use Policy 2014, 38, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicharro Fernández, E.; Galve Martín, A. Alojameintos rurales en España: Entre el crecimiento acelerado y el peligro de una sobredimensión. Geogr. Ser. 2009, 15, 125–137. [Google Scholar]

- Pulina, M.; Giovanna Dettori, D.; Paba, A. Life cycle of agrotouristic firms in Sardinia. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1006–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Riesco, J.C. Un freno a la estacionalidad. Rev. Desarro. Rural 2002, 18, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Comisión Europea. El futuro del Mundo Rural. Comunicación de la Comisión al Parlamento Europeo y al Consejo; Ministro de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación: Madrid, Spain, 1992.

- Álvarez Gómez, J.; Gómez Gil, J.L.; Rodríguez Blanco, J.; Martín Díaz, J.A.; Rodríguez Fraguas, J.A.; Cebrián Calvo, E.; Gómez-Escolar, J.U. El turismo rural abre nuevos caminos. Rev. Desarro. Rural 2002, 18, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Encuesta de Ocupación en Alojamientos de Turismo Rural. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176963&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735576863 (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- PICTE. Plan de Integral de Calidad del Turismo Español. Secretería de Espado de Comercio y Turismo; Ministerio de Economía: Madrid, Spain, 2000.

- Nieto Masot, A.; Cárdenas Alonso, G. El método Leader como política de desarrollo rural en Extremadura en los últimos 20 años (1991–2013). Boletín Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cànoves, G.; Villarino, M.; Herrera, L. Políticas públicas, turismo rural y sostenibilidad: Difícil equilibrio. Boletín Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 2006, 41, 199–217. [Google Scholar]

- Castellano-Álvarez, F.J.; del Río-Rama, M.C.; Álvarez-García, J.; Durán-Sánchez, A. Limitations of Rural Tourism as an Economic Diversification and Regional Development Instrument. The Case Study of the Region of La Vera. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Saraceno, E. The Evaluation of Local Policy Making in Europe:Learning from the LEADER Community Initiative. Evaluation 1999, 5, 439–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loscertales, B. El turismo rural como forma de desarrollo sostenible. El caso de Aragón. Geographicalia 1999, 37, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto Masot, A.; Cárdenas Alonso, G. 25 Años de políticas europeas en Extremadura: Turismo rural y método LEADER. Cuad. Tur. 2017, 39, 386–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharpley, R.; Vass, A. Tourism, farming and diversification: An attitudinal study. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 1040–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto Masot, A.; Cárdenas Alonso, G. The Rural Development Policy in Extremadura (SW Spain): Spatial Location Analysis of Leader Projects. Isprs Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2018, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brezzi, M.; Dijkstra, L.; Ruiz, V. OECD Extended Regional Typology: The Economic Performance of Remote Rural Regions. OECD Publ. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OCDE. Placed-Based Policies for Rural Development. Extremadura. Spain (Case Study). In Proceedings of the 6th Session of the Working Party on Territorial Policy in Rural Areas, Paris, France, 7 December 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto Masot, A.; Gurría Gascón, J.L. Análisis de la población de los programas de desarrollo rural en Extremadura mediante sistemas de información geográfica. Cuad. Geogr. 2005, 36, 479–495. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, J.I.P. Territorio, geografía rural y políticas públicas. Desarrollo y sustentabilidad en las áreas rurales. Boletín Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 2006, 69–95. [Google Scholar]

- MAPA. El estado de la cooperación en LEADER +. Mucho en común. Rev. Desarro. Rural 2004, 26, 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Medio Rural y Marino. Leader en España (1991–2011). Una Conatribución Activa al Desarrollo Rural; Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Medio Rural y Marino: Madrid, Spain, 2011.

- Ministerio de Economía. Plan Integral de Calidad del Turismo Español (PICTE). Secretaría de Estado de Comercio, Turismo y de la Pequeña y Mediana Empresa; Centro de Publicaciones y Documentación del Ministerio de Economía y Hacienda: Madrid, Spain, 1999.

- Nieto Masot, A. El Desarrollo Rural en Extremadura: Las Políticas Europeas y el Impacto de los Programas Leader y Proder; Universidad de Extremadura: Cáceres, Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Plaza Gutiérrez, J.I. Desarrollo y diversificación en las zonas rurales de España: El programa PRODER. BAGE Boletín Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 2005, 39, 399–422. [Google Scholar]

- Cárdenas Alonso, G.; Nieto Masot, A. Towards Rural Sustainable Development? Contributions of the EAFRD 2007–2013 in Low Demographic Density Territories: The Case of Extremadura (SW Spain). Sustainability 2017, 9, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Apostolopoulos, N.; Liargovas, P.; Stavroyiannis, S.; Makris, I.; Apostolopoulos, S.; Petropoulos, D.; Anastasopoulou, E. Sustaining Rural Areas, Rural Tourism Enterprises and EU Development Policies: A Multi-Layer Conceptualisation of the Obstacles in Greece. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, A.; Jansson, T.; Verburg, P.H.; Revoredo-Giha, C.; Britz, W.; Gocht, A.; McCracken, D. Policy reform and agricultural land abandonment in the EU. Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 446–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotiadis, A.; Nuryyev, G.; Achyldurdyyeva, J.; Spyridou, A. The Impact of EU Sponsorship, Size, and Geographic Characteristics on Rural Tourism Development. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Giannakis, E. The role of rural tourism on the development of rural areas: The case of Cyprus. Rom. J. Reg. Sci. 2014, 8, 38–53. [Google Scholar]

- McAreavey, R.; McDonagh, J. Sustainable Rural Tourism: Lessons for Rural Development. Sociol. Rural. 2011, 51, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tirado Ballesteros, J.G.; Hernández Hernández, M. Assessing the Impact of EU Rural Development Programs on Tourism. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2016, 14, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pitarch, M.D.; Arnandís, R. Impacto en el Sector Turístico de las Políticas de Desarrollo Rural en la Comunidad Valenciana (1991–2013). Análisis de las estrategias de fomento y revitalización del turismo rural. Doc. D’anàlisi Geogr. 2014, 60, 315–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Márquez Fernández, D.; Galindo Pérez de Azpillaga, L.; García López, A.M.; Foronda Robles, C. Eficacia y eficiencia de Leader II en Andalucía: Aproximación a un índice-resultado en materia de turismo rural. Geographicalia 2005, 47, 137–152. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Borja, M.A.; Monsalve Serrano, F.; Mondéjar Jiménez, J.A. Impacto de los Programas de Innovación Rural Sobre el Turismo Rural en Cuenca: Un Enfoque de Marketing. In Proceedings of the El Patrimonio Cultural Como Factor de Desarrollo: Estudios Multidisciplinares; Academic Press: Cuenca, Spain, 2006; pp. 375–394. [Google Scholar]

- Toledano Garrido, N.; Gessa Perera, A. El turismo rural en la provincia de huelva. Un análisis delas nuevas iniciativas creadas al amparo de los programas leader ii y proder. Rev. Desarro. Rural Coop. Agrar. 2002, 6, 107–122. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro Valverde, F.A.; Cejudo García, E.; Cañete Pérez, J.A. Análisis a largo plazo de las actuaciones en desarrollo rural neoendógeno. Continuidad de las empresas creadas con la ayuda de LEADER y PRODER en tres comarcas andaluzas en la década de 1990. Ager. Rev. Estud. Sobre Des. Desarro. Rural 2018, 25, 189–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.; Neto, P.; Serrano, M.M. A long-term mortality analysis of subsidized firms in rural areas: An empirical study in the Portuguese Alentejo region. Eurasian Econ. Rev. 2016, 6, 125–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabatzis, G.; Aggelopoulos, S.; Tsiantikoudis, S. Rural development and LEADER+ in Greece: Evaluation of local action groups. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2010, 8, 302–307. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto Masot, A.; Cárdenas Alonso, G.; Costa Moreno, L.M. Principal Component Analysis of the LEADER Approach (2007–2013) in South Western Europe (Extremadura and Alentejo). Sustainability 2019, 11, 4034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Observatorio de Turismo. Boletines Trimestrales de Oferta y Demanda. Available online: https://www.turismoextremadura.com/es/pie/observatorio.html (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- Díaz Aguilar, A.L. Sobre límites, espacios sociales y dialécticas territoriales en el sur de Extremadura (España). Etnicex: Rev. Estud. Etnográficos 2014, 6, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Engelmo Moriche, Á.; Nieto Masot, A.; Mora Aliseda, J. La sostenibilidad económica de las ayudas al turismo rural del Método Leader en áreas de montaña: Dos casos de estudio españoles (Valle del Jerte y Sierra de Gata, Extremadura). Boletín Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 2021, 88, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Hortelano Mínguez, L.A. Desarrollo Rural y Turismo en Castilla y León: Éxitos y Fracasos; Universidad de Salamanca: Salamanca, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mantino, F. L’anomalia Nella PAC: Eterogeneità e Dinamiche del Leader in Italia; Istituto Nazionale di Economia Agraria: Roma, Italy, 2009.

- Lukić, A.; Obad, O. New actors in rural development-the LEADER approach and projectification in Rural Croatia. Sociol. I Prost. Časopis Za Istraživanje Prost. I Sociokulturnog Razvoja 2016, 54, 71–90. [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt, D.; Möllers, J.; Buchenrieder, G. Social Networks and Rural Development: LEADER in Romania. Sociol. Rural. 2012, 52, 398–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, L.; Blank, G.; Gruber, C. Desktop Analysis with SYSTAT; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hamed, M.A.R. Application of Surface Water Quality Classification Models Using Principal Components Analysis and Cluster Analysis. SSRN 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez-Ramíreza, I.; Moreno-Macías, H.; Gómez-Humarán, I.M.; Muratad, C. Conglomerados como solución alternativa al problema de la multicolinealidad en modelos lineales. Rev. Cienc. Clínicas 2014, 15, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, H.; LeDrew, E. Spectral Discrimination of Healthy and Non-Healthy Corals Based on Cluster Analysis, Principal Components Analysis, and Derivative Spectroscopy. Remote Sens. Environ. 1998, 65, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.D.A.C.; Emmett, P.M.; Newby, P.K.; Northstone, K. A comparison of dietary patterns derived by cluster and principal components analysis in a UK cohort of children. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, 1102–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ballas, D.; Kalogeresis, T.; Labrianidis, L. A comparative study of typologies for rural areas in Europe. In Proceedings of the 43rd European Congress of Regional Science Association, Jyvaskyla, Finland, 27–30 August 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Vantas, K.; Sidiropoulos, E. Intra-Storm Pattern Recognition through Fuzzy Clustering. Hydrology 2021, 8, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Pérez, M.; López-Benítez, A.; Rodríguez-Herrera, S.A.; Borrego-Escalante, F.; Ramírez-Meraz, M.; López Benítez, S.R. Análisis conglomerado de 15 cruzas de chile para variables fenológicas y de rendimiento. Agron. Mesoam. 2011, 22, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderberg, M.R. The Broad View of Cluster Analysis; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1973; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Cañete Pérez, J.A.; Cejudo García, E.; Navarro Valverde, F.A. Proyectos fallidos de desarrollo rural en Andalucía. Boletín Asoc. Geogr. Esp. 2018, 270–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cejudo García, E.; Navarro Valverde, F.A. La inversión en los programas de desarrollo rural. Su reparto territorial en la provincia de Granada/Investment in rural development programmes. Its territorial distribution in the province of Granada. An. Geogr. Univ. Complut. 2009, 29, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Cánoves, G.; Villarino, M.; Priestley, G.K.; Blanco, A. Rural tourism in Spain: An analysis of recent evolution. Geoforum 2004, 35, 755–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Henche, B. Características diferenciales del producto turismo rural. Cuad. Tur. 2005, 15, 113–133. [Google Scholar]

- Neumeier, S.; Pollermann, K. Rural tourism as promoter of rural development-Prospects and limitations: Case study findings from a pilot projectpromoting village tourism. Eur. Countrys. 2014, 6, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nieto Masot, A.; Ríos Rodríguez, N. Rural Tourism as a Development Strategy in Low-Density Areas: Case Study in Northern Extremadura (Spain). Sustainability 2021, 13, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| LAG | Municipalities | Population (2019) | Density of Population (Km2) | Old-Age Index 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campiña Sur | 21 | 29,886 | 11.1 | 24.3 |

| Campo Arañuelo | 21 | 35,992 | 24.1 | 17.5 |

| Miajadas-Trujillo | 20 | 30,581 | 13.2 | 24.8 |

| Olivenza | 11 | 31,639 | 19.2 | 20.1 |

| La Serena | 19 | 38,974 | 14.0 | 25.3 |

| Sierra de Gata | 20 | 20,873 | 16.6 | 29.0 |

| Tajo-Salor-Almonte | 15 | 25,858 | 11.9 | 25.4 |

| Tentudía | 9 | 19,886 | 15.5 | 22.2 |

| Valle del Alagón | 27 | 36,649 | 20.2 | 24.4 |

| Valle del Jerte | 11 | 10,786 | 28.8 | 26.6 |

| Total | 174 | 281,124 | 15.8 | 23.5 |

| Typology | Variable | Source of Data |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic | Population 2019 | |

| Population Growth 2019–2000 | National Statistics Institute | |

| Old-Age Index 2019 Population density 2018 | ||

| Economic | Average Income per Capita 2019 | Experimental Atlas of the Spanish National Statistical Institute |

| Unemployment Rate 2018 Percentage of Unemployment Agricultural Sector 2018 Percentage of Unemployment Tertiary Sector 2018 | State Public Employment Service (SPES). It is the ratio between the unemployed population and the potential working age population, 16–65 years old. | |

| Accessibility | Accessibility to motorway | National Geographic Institute (NGI) |

| Variables |

|---|

| Investment per inhabitant |

| Projects per 1000 inhabitants |

| Percentage of Active Projects |

| Percentage of Active Investment |

| Percentage of Active Private Investment |

| Percentage of active non-hotels accommodations |

| Percentage of active hotel accommodations |

| Percentage of active catering service |

| Percentage of active rural accommodations |

| Percentage of financed companies Active in EAFRD |

| Percentage of financed enterprises Active in Leader + |

| Percentage of financed enterprises Active in Leader II |

| LAGs | Investment in Tourism | % Investment in Tourism Supply as a Total | %Private Investment | Projects | % with Respect to Total Projects | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campiña Sur | 3118,315 | 12.2% | 25,584,869 | 61.8 | 34 | 4.6% | 735 |

| Campo Arañuelo | 2464,825 | 10.2% | 24,128,922 | 65.5 | 22 | 4.9% | 448 |

| Miajadas-Trujillo | 3484,672 | 13.3% | 26,284,369 | 68.7 | 44 | 5.4% | 817 |

| Olivenza | 4393,019 | 17.3% | 25,336,804 | 64.2 | 30 | 8.2% | 366 |

| Serena, La | 2825,715 | 8.5% | 33,403,775 | 57.7 | 38 | 5.9% | 645 |

| Sierra de Gata | 5220,789 | 21.8% | 24,003,461 | 65.2 | 99 | 14.6% | 675 |

| Tajo-Salor-Almonte | 5199,020 | 17.3% | 30,063,810 | 72.2 | 53 | 8.6% | 617 |

| Tentudía | 4924,447 | 20.7% | 23,829,479 | 66.6 | 39 | 9.6% | 405 |

| Valle del Alagón | 5017,349 | 18.2% | 27,577,741 | 60.0 | 45 | 6.9% | 656 |

| Valle del Jerte | 4563,585 | 20.3% | 22,440,377 | 64.8 | 76 | 9.7% | 786 |

| Total | 41,211,740 | 15.7% | 263,199,071 | 65.0 | 480 | 7.8% | 6150 |

| LAG | Municipalities | Municipalities with Investment |

|---|---|---|

| Campiña Sur | 21 | 13 (61.9%) |

| Campo Arañuelo | 21 | 12 (57.1%) |

| Miajadas-Trujillo | 20 | 9 (45.0%) |

| Olivenza | 11 | 7 (63.6%) |

| Serena, La | 19 | 13 (68.4%) |

| Sierra de Gata | 20 | 18 (90.0%) |

| Tajo-Salor-Almonte | 15 | 11 (73.3%) |

| Tentudia | 9 | 9 (100%) |

| Valle del Alagón | 27 | 18 (66.7%) |

| Valle del Jerte | 11 | 9 (81.8%) |

| Total | 174 | 199 (68.4%) |

| Variable | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population 2019 | 100 | 4159 | 4597 | 1744 |

| Population Growth 2019–2000 | −16.6 | 10.4 | −10.4 | 12.0 |

| Population density 2018 | 3.4 | 34.8 | 19.9 | 30.6 |

| Old-Age Index 2019 | 40.0 | 17.6 | 18.3 | 16.8 |

| Average Income per Capita 2019 | 11,168 | 8654 | 8951 | 16,482 |

| % Unemployment Agricultural Sector 2018 | 0 | 18.7 | 6.4 | 4.4 |

| % Unemployment Tertiary Sector 2018 | 66.7 | 64.2 | 68.9 | 63.4 |

| Unemployment Rate 2018 | 5.9 | 11.9 | 23.2 | 12.5 |

| Accessibility to motorway | 13.4 | 23.0 | 23.2 | 0.9 |

| Investment per inhabitant | 2604 | 171.7 | 189.5 | 0.8 |

| Projects per 1000 inhabitants | 10 | 0.2 | 1.3 | 0.5 |

| Percentage of Active Projects | 100 | 100 | 40 | 0.0 |

| Percentage of Active Investment | 100 | 100 | 21.2 | 0.0 |

| Percentage of Active Private Investment | 100 | 100 | 12.5 | 0.0 |

| Non-hotels | 0.0 | 0.0 | 50 | 0.0 |

| Hotels | 0.00 | 100 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Catering Service | 0.0 | 0.0 | 50 | 0.0 |

| Rural | 100 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| EAFRD | 0.0 | 100 | 21.6 | 0.0 |

| Leader + | 100 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Leader II | 0.0 | 0.0 | 20.9 | 0.0 |

| Variable | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. Municipalities | 34 | 43 | 35 | 7 |

| Population 2019 | 768 | 3988 | 1246 | 484 |

| Population Growth 2019–2000 | −19.1 | −10.3 | −22.3 | −9.8 |

| Population density 2018 | 7.6 | 19.4 | 10.3 | 8.6 |

| Old-Age Index 2019 | 33.1 | 23.4 | 29.2 | 28.8 |

| Average Income per Capita 2019 | 10,659 | 9794 | 9722 | 13,448 |

| % Unemployment Agricultural Sector 2018 | 10.9 | 14.6 | 12.4 | 6.5 |

| % Unemployment Tertiary Sector 2018 | 68.7 | 63.3 | 63.7 | 77.6 |

| Unemployment Rate 2018 | 14.1 | 15.9 | 15 | 16.1 |

| Accessibility to motorway | 17.2 | 19.4 | 22 | 6.7 |

| Investment per inhabitant | 960 | 177 | 295 | 701 |

| Projects per 1000 inhabitants | 11 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

| Percentage of Active Projects | 81.0 | 81.0 | 19.8 | 0 |

| Percentage of Active Investment | 91.5 | 84.8 | 15.5 | 0 |

| Percentage of Active Private Investment | 92.0 | 78.9 | 16.8 | 0 |

| Non-hotels | 100 (7) | 88.2 (15) | 75.0 (3) | 0 |

| Hotels | 100 (2) | 74.0 (20) | 50.0 (1) | 0 |

| Catering Service | 69.2 (18) | 72.0 (49) | 38.0 (8) | 0 |

| Rural | 80.5 (62) | 71.6 (48) | 23.2 (10) | 0 |

| EAFRD | 94.7 (36) | 82.1 (69) | 50.0 (7) | 0 |

| Leader + | 84.6 (33) | 78.5 (33) | 23.5 (4) | 0 |

| Leader II | 38.4 (20) | 49.1 (30) | 17.7 (11) | 0 |

| Success Rate | High | High-Moderate | Low | Unsuccessful |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Engelmo Moriche, Á.; Nieto Masot, A.; Mora Aliseda, J. Economic Sustainability of Touristic Offer Funded by Public Initiatives in Spanish Rural Areas. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4922. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094922

Engelmo Moriche Á, Nieto Masot A, Mora Aliseda J. Economic Sustainability of Touristic Offer Funded by Public Initiatives in Spanish Rural Areas. Sustainability. 2021; 13(9):4922. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094922

Chicago/Turabian StyleEngelmo Moriche, Ángela, Ana Nieto Masot, and Julián Mora Aliseda. 2021. "Economic Sustainability of Touristic Offer Funded by Public Initiatives in Spanish Rural Areas" Sustainability 13, no. 9: 4922. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094922