Social Exclusion and Effectiveness of Self-Benefit versus Other-Benefit Marketing Appeals for Eco-Friendly Products

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Social Exclusion

2.2. Message Appeal Type

2.3. The Present Research

3. Experiment

3.1. Methods

3.2. Results

3.2.1. Manipulation Check

3.2.2. Purchase Intention of Upcycling Products

3.2.3. Perceived Stability of Social Exclusion

4. Discussion

4.1. Research Summary and Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Why Clothes Are so Hard to Recycle. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200710-why-clothes-are-so-hard-to-recycle (accessed on 13 July 2020).

- Singh, J.; Sung, K.; Cooper, T.; West, K.; Mont, O. Challenges and Opportunities for Scaling up Upcycling businesses–The Case of Textile and Wood Upcycling Businesses in the UK. Resource. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 150, 104439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- About 1.7 Billion People Belong to the Global “Consumer Class”. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/consumerism-earth-suffers (accessed on 12 January 2004).

- Baumeister, R.F.; DeWall, C.N.; Ciarocco, N.J.; Twenge, J.M. Social Exclusion Impairs Self-Regulation. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 88, 589–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwilinski, A.; Vyshnevskyi, O.; Dzwigol, H. Digitalization of the EU Economies and People at Risk of Poverty or Social Exclusion. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjåstad, H.; Zhang, M.; Masvie, A.E.; Baumeister, R. Social exclusion reduces happiness by creating expectations of future rejection. Self Identity 2021, 20, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.D. Ostracism. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2007, 58, 425–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primack, B.A.; Shensa, A.; Sidani, J.E.; Whaite, E.O.; yi Lin, L.; Rosen, D.; Colditz, J.B.; Radovic, A.; Miller, E. Social Media use and Perceived Social Isolation among Young Adults in the US. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The Need to Belong: Desire for Interpersonal Attachments as a Fundamental Human Motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeWall, C.N.; Twenge, J.M.; Gitter, S.A.; Baumeister, R.F. It’s the Thought that Counts: The Role of Hostile Cognition in Shaping Aggressive Responses to Social Exclusion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 96, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Baumeister, R.F.; DeWall, C.N.; Ciarocco, N.J.; Bartels, J.M. Social Exclusion Decreases Prosocial Behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, W.L.; Pickett, C.L.; Jefferis, V.; Knowles, M. On the Outside Looking in: Loneliness and Social Monitoring. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2005, 31, 1549–1560. [Google Scholar]

- Maner, J.K.; DeWall, C.N.; Baumeister, R.F.; Schaller, M. Does Social Exclusion Motivate Interpersonal Reconnection? Resolving the “Porcupine Problem”. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 92, 42–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Han, S. The effect of the social exclusion experience on the consumer’s response to the situation where they consume the same product as others. Korean J. Consum. Advert. Psychol. 2014, 15, 555–574. [Google Scholar]

- Mead, N.L.; Baumeister, R.F.; Stillman, T.F.; Rawn, C.D.; Vohs, K.D. Social Exclusion Causes People to Spend and Consume Strategically in the Service of Affiliation. J. Consum. Res. 2011, 37, 902–919. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, K.D.; Cheung, C.K.; Choi, W. Cyberostracism: Effects of being Ignored over the Internet. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 79, 748–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Baumeister, R.F.; Tice, D.M.; Stucke, T.S. If You can’t Join them, Beat them: Effects of Social Exclusion on Aggressive Behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 81, 1058–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, E.W.; Xu, J.; Ding, Y. To be Or Not to be Unique? The Effect of Social Exclusion on Consumer Choice. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 40, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar]

- Brunel, F.F.; Nelson, M.R. Explaining Gendered Responses to “help-Self” and “help-Others” Charity Ad Appeals: The Mediating Role of World-Views. J. Advert. 2000, 29, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.J.; Vandenbosch, M.; Antia, K.D. An Empathy-Helping Perspective on Consumers’ Responses to Fund-Raising Appeals. J. Consum. Res. 2008, 35, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, Y. The Effects of Processing Fluency in Prosocial Campaigns: Effort for Self-Benefit Produces Unpleasant Feelings. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, K.; Peloza, J. Self-Benefit Versus Other-Benefit Marketing Appeals: Their Effectiveness in Generating Charitable Support. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, J.I.; Steg, L. Value Orientations to Explain Beliefs Related to Environmental Significant Behavior: How to Measure Egoistic, Altruistic, and Biospheric Value Orientations. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 330–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C. New Environmental Theories: Toward a Coherent Theory of Environmentally Significant Behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K.; Crane, A. Green Marketing: Legend, Myth, Farce or Prophesy? Qual. Mark. Res. Int. J. 2005, 8, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P. Understanding Household Garbage Reduction Behavior: A Test of an Integrated Model. J. Public Policy Mark. 1995, 14, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, T.H.; Yoon, S.; Kim, S.; Kim, Y. Social exclusion influences on the effectiveness of altruistic versus egoistic appeals in charitable advertising. Mark. Lett. 2019, 30, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, Z.; DeWall, C.N. Social Exclusion and Consumer Switching Behavior: A Control Restoration Mechanism. J. Consum. Res. 2017, 44, 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matz, S.C.; Netzer, O. Using Big Data as a Window into Consumers’ Psychology. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2017, 18, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B. Attribution, Emotion, and Action. In Handbook of Motivation and Cognition: Foundations of Social Behavior; Sorrentino, R.M., Higgins, E.T., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986; pp. 281–312. ISBN 0-89862-667-6. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Shrum, L.J. Conspicuous Consumption Versus Charitable Behavior in Response to Social Exclusion: A Differential Needs Explanation. J. Consum. Res. 2012, 39, 530–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Shrum, L.J.; Yi, Y. The Role of Cultural Communication Norms in Social Exclusion Effects. J. Consum. Psychol. 2017, 27, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molden, D.C.; Lucas, G.M.; Gardner, W.L.; Dean, K.; Knowles, M.L. Motivations for Prevention or Promotion Following Social Exclusion: Being Rejected Versus being Ignored. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2009, 96, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Condition | N | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social exclusion | 97 | 5.9330 | 0.970 |

| Social inclusion | 83 | 3.5904 | 1.845 |

| t (p) | 10.876 (0.000) *** | ||

| Question | Condition | N | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The ad emphasized self-focused benefits | other-benefit appeal | 99 | 2.77 | 1.406 |

| self-benefit appeal | 81 | 4.47 | 1.526 | |

| t (p) | −7.711 (0.000) *** | |||

| The ad emphasized other-focused benefits | other-benefit appeal | 99 | 5.06 | 1.557 |

| self-benefit appeal | 81 | 3.46 | 1.509 | |

| t (p) | 6.993 (0.000) *** | |||

| DV | IV | SS | d.f. | MS | F(p) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purchase intention | Modified Model | 50.334 | 3 | 16.778 | 9.008 | 0.000 |

| intercept | 2582.507 | 1 | 2582.507 | 1400.441 | 0.000 | |

| Appeal type | 16.887 | 1 | 16.887 | 9.157 | 0.003 ** | |

| Social state | 0.120 | 1 | 0.120 | 0.065 | 0.799 | |

| Appeal type × Social state | 28.890 | 1 | 28.890 | 15.666 | 0.000 *** | |

| error | 324.556 | 176 | 1.844 | |||

| sum | 2955 | 180 | ||||

| Modified sum | 374.890 | 179 |

| Appeal Type | N | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upcycling products Purchase intention | Other-benefit appeal | 53 | 3.0802 | 1.3630 |

| Self-benefit appeal | 44 | 4.5057 | 1.4552 | |

| t (p) | −4.9473 (0.000) *** | |||

| Appeal Type | N | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upcycling products Purchase intention | Other-benefit appeal | 46 | 3.9402 | 1.382 |

| Self-benefit appeal | 37 | 3.7500 | 1.190 | |

| t (p) | 0.673 (0.503) | |||

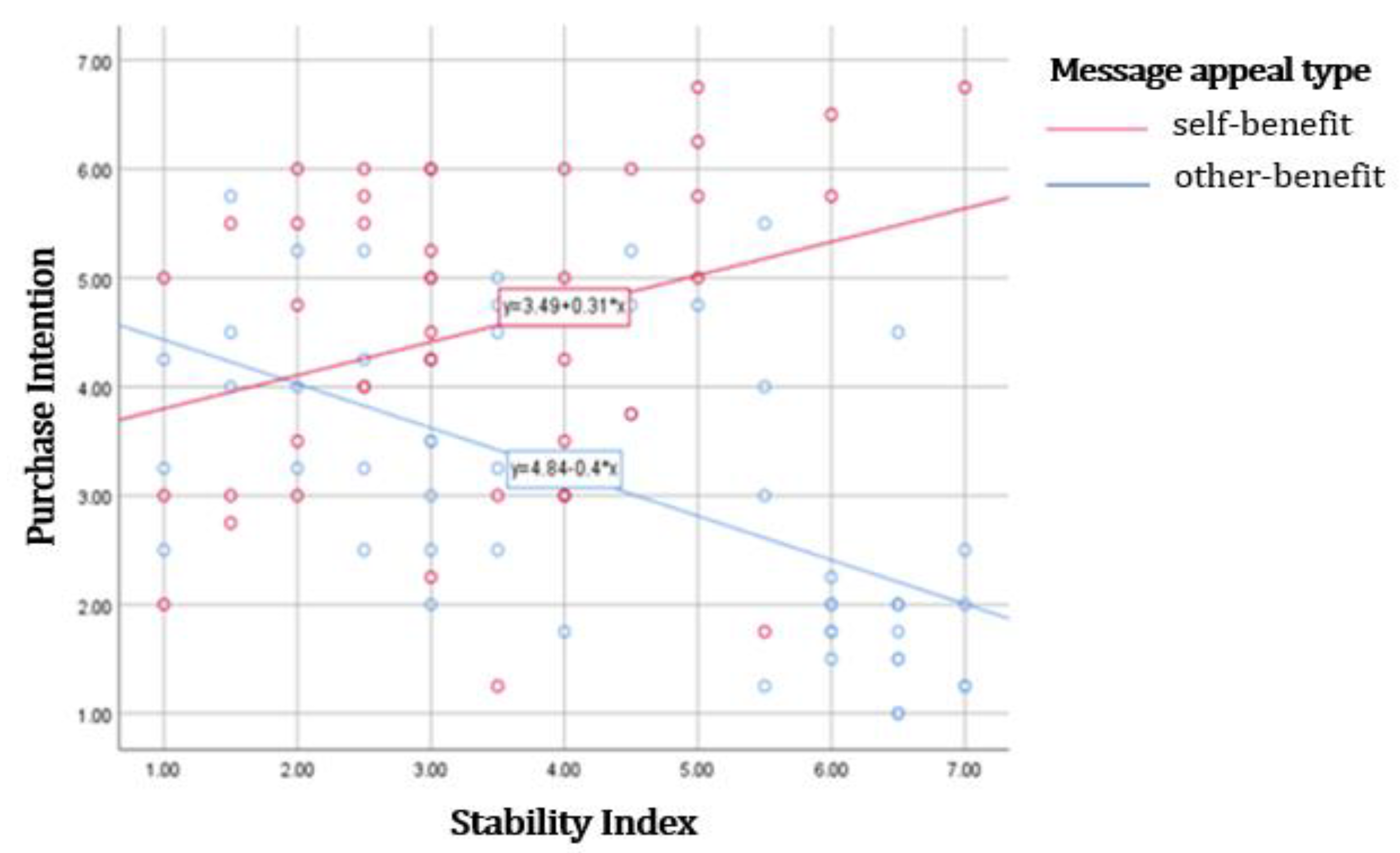

| Coefficient | Se | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appeal type | −1.3426 | 0.6431 | −2.0876 | 0.0396 | −2.6198 | −0.0655 |

| Perceived stability | −1.1152 | 0.2243 | −4.9713 | 0.000 | −1.5607 | −0.6697 |

| Interaction | 0.7108 | 0.1610 | 4.4147 | 0.000 | 0.3911 | 1.0305 |

| Perceived Stability | Effect | Se | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0000 | −0.6319 | 0.5013 | −1.2604 | 0.2107 | −1.6274 | 0.3637 |

| 2.0000 | 0.0789 | 0.3753 | 0.2103 | 0.8339 | −0.6663 | 0.8242 |

| 3.5000 | 1.1451 | 0.2689 | 4.2577 | 0.000 | 0.6110 | 1.6792 |

| 4.6000 | 1.9270 | 0.3102 | 6.2117 | 0.000 | 1.3109 | 2.5430 |

| 6.0000 | 2.9221 | 0.4662 | 6.2672 | 0.000 | 1.9962 | 3.8479 |

| 7.0000 | 3.6328 | 0.6051 | 6.0038 | 0.000 | 2.4312 | 4.8344 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, A.; Han, S. Social Exclusion and Effectiveness of Self-Benefit versus Other-Benefit Marketing Appeals for Eco-Friendly Products. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5034. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095034

Yu A, Han S. Social Exclusion and Effectiveness of Self-Benefit versus Other-Benefit Marketing Appeals for Eco-Friendly Products. Sustainability. 2021; 13(9):5034. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095034

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Ahyoung, and Seunghee Han. 2021. "Social Exclusion and Effectiveness of Self-Benefit versus Other-Benefit Marketing Appeals for Eco-Friendly Products" Sustainability 13, no. 9: 5034. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095034

APA StyleYu, A., & Han, S. (2021). Social Exclusion and Effectiveness of Self-Benefit versus Other-Benefit Marketing Appeals for Eco-Friendly Products. Sustainability, 13(9), 5034. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13095034