1. Introduction

Latino vendor markets (LVM), classified in the U.S. as flea markets or swap meets, are the focus of this paper. The role that city planning plays in supporting, or not, LVM through planning policies is explored in this paper. While recent market studies emphasize the cultural and social value of flea markets and swap meets for immigrant communities [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5], few explore this phenomenon through the lens of urban planning [

6,

7]. Morales explores how economic practices are embedded in the social organization of markets and proposes that planners develop an integrated planning approach for supporting markets [

3,

6]. Following Morales’ work, three studies explored Latinos markets in California and Texas [

4,

8,

9]. These anthropological studies find that LVM produce social and economic benefits, such as human capital, sense of place, cultural identity [

8,

9], as well as access to food and sociocultural benefits for Latinos, mostly of Mexican American decent [

4]. As case studies, they explore the links between the human and economic dimensions of LVM, a far advancement from previous studies. The purpose of this paper is to explore what role urban planning policies play in supporting LVM. The research uses four selected case studies in the states of California and Texas to explore these issues.

Flea markets closely resemble the oldest forms of market in peasant societies [

10,

11,

12]. Early studies of flea markets and swap meets in the U.S. brought attention to markets as “action scenes” where action occurs in situations where people pit themselves against one another in the context of exchange [

13], as the historical leftovers of “archaic marketplaces” in peasant societies [

14] that evolved over time in response to societal needs [

15]. While flea markets and swap meets have been qualified as primitive, archaic, and anachronistic spaces for exchange of used goods [

12], others saw them as opportunities to explore economic activity arguing that they should not be classified as second-order market systems, meaning less than other markets like farmers markets [

16,

17,

18]. The role of marketplaces in the U.S. has indeed shifted in response to societal needs: economic, social and political. In early 20th century New York City, unauthorized street vendors were forced to relocated to locations considered to be “out of the way,” such as underneath the Manhattan, Williamsburg, and Queensboro bridges and eventually to enclosed markets [

19]. Outdoor markets declined during the mid-twentieth century due to the growth of the grocery store industry [

15,

20]. Technological advances allowed for mass distribution of products that, for a long time, were only accessible locally at markets. At the same time, suburban malls emerged as a model of commerce and exchange that tried to replicate elements of urban life [

21], much like New Urbanist developments aim at re-create a nostalgia for city centers [

22].

Much like the New York City street vendors of early 20th century, flea markets and swap meets, today, are facing dilemmas. In a recent study on private markets, Mörtenböck & Mooshammer (2015) state, “unbuilt-on plots of these sizes have come to represent rare and highly valued development opportunities that can achieve huge profits when earmarked for construction of shopping malls, campus expansions, and gated communities” (p. 163). Private property owners operating the markets are reacting to market pressures and evicting vendors using a 30-day notice as they prepare to sell their land for redevelopment purposes [

23]. Private property owners and cities determine the fate of markets as they respond to social needs and market pressures. As land has become more valuable in the city, markets have moved outside the city center to inaccessible and less inhabited areas. Despite this trend, some cities in the U.S. (such as Seattle, Philadelphia, Washington D.C., and Detroit) have maintained a strong market culture allowing their historic markets to remain established in the city center. These cities recognized that as a centrally located institution in a growing city, markets could offer affordable opportunities for small business entrepreneurs, while also serving as a “vital lifeline” to connect consumers to produce [

3,

6,

17,

24,

25].

LVM are the product of the evolution of various building and urban typologies. In the late 20th century, swap meets and markets became hubs and centers for Latino owned businesses [

23]. Until the 1960s, flea markets and swap meets were generally used by white vendors who sold mostly secondhand goods outdoors. In places like southern California, swap meets were temporary outdoor markets that occupied parking lots of drive-in theatres [

26,

27]. Drive-ins defined an American culture that embraced individualism and autonomy granted by automobile ownership. Their decline in the 1980′s gave rise to LVM on these sites [

27]. The atypical adaptive reuse of space gave new meaning to a typology centered on public gathering and socializing. In the 1970s, Latino immigrants started selling goods and affordable services at California swap meets and began to replicate the design and organization of

tianguis, or open-air markets in Mexico [

26]. At the same time, the decline of drive-in movie theaters led to a proliferation of swap meets and flea markets, driven by property owners seeking to bolster flagging profits by renting their properties during the day [

26]. During the 1980s and 1990s, swap meets began to appear as indoor markets in what had become vacant and underutilized industrial buildings or shopping centers [

23,

26].

The term “Latinos” refers to a pan-ethic group that generally identifies with Latin American countries [

28]. In addition to Latino, other common terms such as “Hispanic” or “Chicano” are also used in some cases to refer to more regional specific distinctions [

29]. For the purpose of consistency, this paper uses the term Latino as the common designation. Latinos are one of the largest and fastest growing ethnic minorities in the U.S. [

30], yet there is a need to better understand their role in the shaping of cities. Since 2000, Latino Urbanism has emerged as a theoretical and practical approach to community development and planning policy that seeks to understand how socio-economic and political change affects the nature and functioning of cities with large Latino populations over time [

31,

32]. Specifically, Latino Urbanism is concerned with understanding the extent to which Latino lifestyle preferences and experiences are tied, or not, to a baseline of opportunities, such as standard of living and educational attainment; more specifically, Latino Urbanism explores how classist and racialized public policy and civic practices impact Latinos [

32]. Two pervasive barriers to the inclusion of this demographic in planning is (1) the lack of understanding of the ways in which these communities socially construct place and (2) the contribution that sociocultural infrastructure and support networks afford residents [

28,

32,

33,

34]. Latinos have the highest rate of new entrepreneurs in the U.S. [

35]. In 2018, the roughly 5-million Latino-owned businesses earned approximately

$400 million in revenue and they employed around 3 million people [

35]. If Latinos in the U.S. were an independent country, the Latino Gross Domestic Product (GDP) would be the seventh largest in the world. In 2015, the GDP produced by Latinos in the United States was

$2.13 trillion, larger than the GDPs of India, Italy, or Canada [

35].

At the turn of the 20th century, planning began to implement policies framed through the lens of sustainability, and more recently a focus on equity [

36,

37]. Smart Growth planning, for example, is a comprehensive strategy of regional sustainability that targets economic efficiency, environmental protection, a high quality of life and social equity that is potentially achievable through negotiated land use polices, with an emphasis on transit-oriented land use [

36]. Among other things, smart growth envisions compact development and redevelopment of existing cores, limited suburban sprawl and transit-oriented land use. Although Smart Growth planning assumes development through an equity lens, it has largely failed to engage with communities of color, including Latinos [

38]. Within these contemporary planning frameworks, economic development and quality of life are often prioritized over social equity objectives [

36,

38,

39]. This paper explores the role that city planning plays in supporting, or not, LVM through planning policies, and in turn addressing the economic and social role of Latinos in the U.S. city.

2. Materials and Methods

Human behavior analysis requires context specific study, and case studies are a type of context-dependent form of knowledge production [

40,

41]. As a qualitative method, the use of case studies allows researchers to explore complexities beyond the scope of a more controlled approach [

40]. The closeness of the case study to real-life situations and its multiple wealth of details are important in the development of a nuanced view of reality, including the view that human behavior is not easy to simply [

42]. A key characteristic of case studies is the use of multiple sources of evidence [

40]. Case study is a main method that hold different sub-methods within such as: interviews, observations, document and record analysis, and so on [

40].

Case studies are useful for both generating and testing of hypotheses, but they are not limited to these research activities alone [

42]. One advantage of the case study is that allows for a closing-in of a real-life situations and test views directly in relation to phenomena as they unfold in place [

42]. Ethnographic case studies are often expected to represent larger entities, specifically when researching the urban poor or immigrant groups; nevertheless, the precise relationship between such cases and the larger populations they are expected to represent remains unclear [

43].

There are high concentrations of Latinos along the U.S.-Mexico border, and moving north the number and concentration of Latinos decreases. To capture this fact, this study tested the research design both on border counties (San Diego County, CA, USA and Cameron County, TX, USA), and in more in-land urban contexts (Los Angeles County, CA, USA and Harris County, TX, USA). There are two counties on the U.S.-Mexico border of California: Imperial and San Diego Counties. Imperial County a rural with a total population of approximately 180,000 [

29,

44]. El Centro, its largest city, has a total population of approximately 44,000 [

29]. Given its rural classification, the study did not select Imperial County but selected the more populous San Diego County to ensure the possibility of a larger Latino population sample, and possible markets.

Five conditions were used to select the markets: (1) only registered markets were in a potential sample pool, identifiable through multiple data sources to ensure that only markets operating in the formal sector would be selected, registration was a necessary component of the selection process to ensure that the length of establishment of potential markets could be confirmed; (2) all markets corresponded to the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) code 453310, “used merchandise stores,” the classification for flea markets and swap meets; (3) the markets were open-air as these have been classified as derivatives of traditional market typologies [

9,

14] allowing for the study to address market links to public amenities, the study assumes open-air markets are visited most frequently during the spring and summer months thus markets are observed during temperate weather seasons.; (4) they had to be in operation for more than ten years to explore nuances in length of business operations; and (5) a minimum of 500 vendor stalls to ensure that a critical mass of vendors would be present for observation. To ensure comparable sample groups, the minimum vendor threshold controlled for excluding smaller markets, which were less common.

A total of thirteen markets met the selection criterion: four in Los Angeles County, four in Harris County, four in San Diego County, and one in Cameron County. Following Belk et al., (1988) sample methodology, the markets were visited for preliminary fieldwork to verify the existence of critical mass of customers and vendors; after that pre-selection one market was purposely selected per region. The selected markets were two border case studies: Spring Valley Swap Meet (San Diego County, CA, USA) and the Seventy-Seven Flea Market (Cameron County, TX, SUA); and two in-land case studies: the Roadium Open Air Market (Los Angeles County, CA, USA) and Sunny Flea Market (Harris County, TX, USA).

The selected markets were visited over a four-month period during the spring and summer of 2015. Primary collected data for the four cases included: numerous on-site observations, 198 vendor and customer surveys, four key informant interviews with market management and city planning officials, and three focus group sessions with vendors and city officials. Secondary data included: U.S. Census data, Reference USA, Yelp, business websites, vendors and market-related Facebook pages, and local, county, and state policies. Policy analysis focused on profiling policy for the markets and vendors. The analysis documented both restrictions and support for market management in their operations of LVMs in California and Texas, in addition to regulations enforced for vendors operating at LVMs. The aforementioned methodologies of this mixed-methods case study research represent the scope of the larger project on LVMs. In this paper, findings extracted focus only presenting a basic profile of the marketplace and people, both customers and vendors, followed by a synthesis of the policy analysis.

Two survey instruments were designed, based on questions from previous market studies [

12,

17], one for customers and one for vendors; surveys were administered in person in English and Spanish. A total of 120 vendors and 78 customers surveys, were collected. The consumer survey consisted of 29 questions focusing on the following areas: spatial (12), social (9), economic (7), and general demographics (8). Customers were approached in rest areas or pedestrian corridor intersections at each market where customers tend to cluster and selected at random by counting every fourth person encountered. Even though there were more customers than vendors at all of the markets, customers were less willing to stop and answer the survey questionnaire.

The vendor survey consisted of 57 questions focusing on these topics: spatial (12), social (5), institutional (13), economic (18), and general demographics (9). A stratified random sampling method was applied to ensure vendors were sampled evenly across the actual vendor population and spatial distribution at the market. Markets are typically organized along multiple rows of vendor stalls. After identifying the number of rows in each of the markets (11 in Los Angeles County, 3 in Harris County, 10 in San Diego County, and 9 in Cameron County), an equal but random number of vendors were sampled per row by choosing every fifth vendor stall. If the randomly selected vendor did not wish to participate in the survey, the selection was substituted by proceeding to the following vendor stall number. Based on the stratified sample and the potential sample pool, the vendor survey response rate ranged from 10% (Cameron County) to 25% (Los Angeles County). The study attributes vendors’ willingness to participate in the survey to two factors: there is a level of perceived trust with the interviewer as a Spanish speaking Latina, and vendors’ desire to address the operations of the market. Quantitative and qualitative data were extracted from the survey dataset in support of a mix-methods analysis of case studies. The study uses descriptive statistics to infer the general profile of the population at each market. The qualitative analysis focuses on documenting site conditions, and the role of the city in facilitating their operation.

Three focus groups were designed as a tool to gain a deeper understanding of institutional frameworks shaping the operation of LVM. As the pilot study site, Cameron County was selected for in-depth analysis through the focus groups. Planning for the focus groups began through conversations with the city’s planning department. The study proposed facilitating one focus group with all stakeholders at the table. The city’s planning department, however, recommended that three separate meetings take place: one for vendors, one for city leaders, and a third where both sides could come together and discuss views. They city saw the focus groups as an opportunity to help portray issues of perception in relation to planning frameworks for the city from all sides of the spectrum. Participant stakeholders included: local market vendors, market management, and city leaders. The same set of questions was presented at the first two focus groups, and a synthesis of the responses from both sessions was discussed at the third session. The aim of this third session was to synthesize the response of vendors and city leaders. Each focus group session ran for two hours. A total of 40 people participated in the three focus groups. The focus groups were moderated by the primary investigator. Key findings from the focus groups are presented in a separate forthcoming publication.

This study was limited in scope by focusing on specific geographic contexts; however, the methodology could potentially be applied in different geographic contexts, helping to triangulate findings from the wider U.S. Latino population. Some may consider the relatively small sample size, somewhere between forty to fifty vendors and customers survey per market a potential limitation. To address this, the survey findings were triangulated with observations and secondary data. Studies with small samples have the capacity to provide meaningful contributions to knowledge, provided the language and assumptions through which they are interpreted differ [

43]. The significance of case studies is in what they tell us about society as a whole rather than about the population of similar cases [

43,

45]. Statistical generalizability about a wider, at large population group, should not be intent of case study; the purpose is to understand the case, not to generalize [

43]. One way to address the problem of generalization in case studies is the use of the extended case method, which requires that a case study be analyzed in relation to its broader social forces [

43,

45,

46]. In the context of this study, the mixed-method approach of the case study analysis allows for an exploration of context-specific knowledge for LVMs in California and Texas.

3. Results: Overview of Case Studies

3.1. Los Angeles County Market

The Los Angeles County market case study is approximately 15 miles from Downtown Los Angeles, California in the city of Torrance. According to the study survey, however, all of the vendors and customers sampled live in surrounding cities within L.A. County, and none reside in Torrance. The market is located off W. Redondo Beach Boulevard, a primary arterial connecting to Highway 405 half a mile west of the market. It is surrounded by low-density development, predominately single family residential typical of a sprawling landscape. According to the study survey, all of the customers sampled arrived at the market in their personal vehicle.

The Los Angeles County market operates onsite a debunked drive-in theatre, a common practice of many California swap meets. The drive-in opened in 1953, and during the 1960s the site began hosting swap meets during the day as a secondary activity when the theatre was not in operation [

47]. During the 1980s the drive-in theater industry saw a decline and like many across the country, the drive-in was closed. The site’s secondary program of a swap meet became its primary use. The Los Angeles County market has been operating as a swap meet for over 50 years and has been managed by the same market owner since 1981 [

48].

The market operates on an 11-acre facility, is open seven days a week and sees an average of 10,000 shoppers on weekends with an additional 30,000 during the week [

49]. The market has the capacity to host approximately 617 vendors. On site inventory found the market at 91.7% occupancy. Entry to the market costs

$0.75 per person; children under five receive free admission.

3.2. Harris County Market

The Harris County market case study is located 11 miles north of downtown Houston, Texas, outside the city limits boundary of Houston, in an unincorporated area of Harris County. It is part of the Airline Improvement District created in 2005 by the Texas Legislature (79 (R) HB 1458). The purpose of the district is to supplement services to Harris County. The Airline Improvement District is approximately 4 square miles; it has a population of approximately 16,500 residents, more than 60% of which is Latino [

50].

The Harris County market operates on a 23-acre facility. It is open Saturdays and Sundays, and sees an average of 50,000 visitors every weekend. According to the study inventory, the market has capacity for 717 vendors and was found to be at 93% occupancy. Entrance to the market is free, however customer parking cost

$2 per vehicle. The market has been owned and operated by an Asian American family since opening in 1984 [

51]. In 1998, the same family incorporated the market as a business under the Sunny Flea Market Investment Inc. but remain the market managers.

The Harris County market is located on Airline Drive, a primary arterial road running parallel to Interstate 45 and Hardy Toll Road. There are six flea markets along Airline Drive, all of which are within the Airline Improvement District. The Harris County market is the largest market in the improvement district and is adjacent four other markets: Tia Pancha Flea Market is located north of the site; Sin Ta Flea Market is located north of Tia Pancha Flea Market; and Mercado Sabadomingo is located across Airline Drive, east of the Harris County market. Land uses for properties along Airline Drive are commercial and industrial; those to the east and west of Airline are primarily single-family residential.

3.3. San Diego County Market

The San Diego County market is approximately 13 miles from the central business district in downtown San Diego, California. It is located off State Highway 54 and connects to both Highway 5 and Highway 805, which bridge over into Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico. It is located Spring Valley, California an unincorporated area of San Diego County. Spring Valley is a census-designed place with a population of approximate 28,000 people [

52].

The San Diego County market began operating as an auction yard in 1969 before converting to operate as a swap meet in 1970 after the owners obtaining a swap meet business license. The market has been owned and operated by the same family since its opening; in addition to this location, the family owns other swap meets in San Diego County, some operating on debunked drive-in theatre sites.

Development surrounding the market is low density, predominately single-family residential. A series of big-box developments anchoring K-Mart and Albertsons are located along Highway 54 north of the market. Adjacent properties west and south of the market, between the market and the highway, are vacant. The properties north of the market are a pre-school, a community center, and a park. The San Diego market occupies approximately 37 acres: 11 are for the market vending area; and the remaining are used for customer parking. It is open Saturdays and Sundays and is visited by approximately 20,000 people every weekend [

53]. The market has a leasing capacity to host up to 1110 vendors. According to the on-site inventory, it is estimated to have a 70% occupancy rate. Customers are required to pay a

$1.00 fee to enter the market.

3.4. Cameron County Market

The Cameron County market is located in the city of Brownsville, Texas, and approximately 8 miles from the downtown. The market is located off U.S. Highway 77, the primary arterial road connecting the market to the city and south into Mexico. Union Pacific freight rail lines border the market to the west. Immediately south of the market is a residential subdivision, and light industrial properties neighbor the market to the north. This is predominately a suburban spatial landscape: low density development, and big box shopping centers located off the highway to the south of the market. According to the study survey and backed by observations, all of the customers sampled arrived at the market in their personal vehicle.

The Cameron County market is a family owned and operated business since 1981 [

54]. In the 1970′s a husband and wife from Mexico immigrated to the United States with eight children and decided to start a sheet metal business that remains in operation today. The family would spend weekends visiting flea markets across the Rio Grande Valley, many of which no longer exist. Following a decade long business analysis, in 1981 the parents decided to open their own flea market and used the sheet metal from their first business as the primary material for the construction of the market. 35 years later, the Seventy-Seven Flea Market is the largest flea market in Cameron County. According to the tax appraisal district, the current market rate value for the property is approximately 3.9 million dollars [

55].

The market operates on a 74-acre site; it is open on Saturdays and Sundays and is visited by approximately 30,000 every weekend. According to the market management, approximately 5000 cars enter the market on a typical Sunday. Based on this estimate and observed group sizes based on walk-in observations, the study estimates the number of people at the market. According to the study inventory, the market has a capacity of 1461 leasable vendor stalls. Based on the market inventory, on a typical weekend the market occupancy is estimated at 87% of its capacity.

3.5. Synthesis of Case Study Profiles

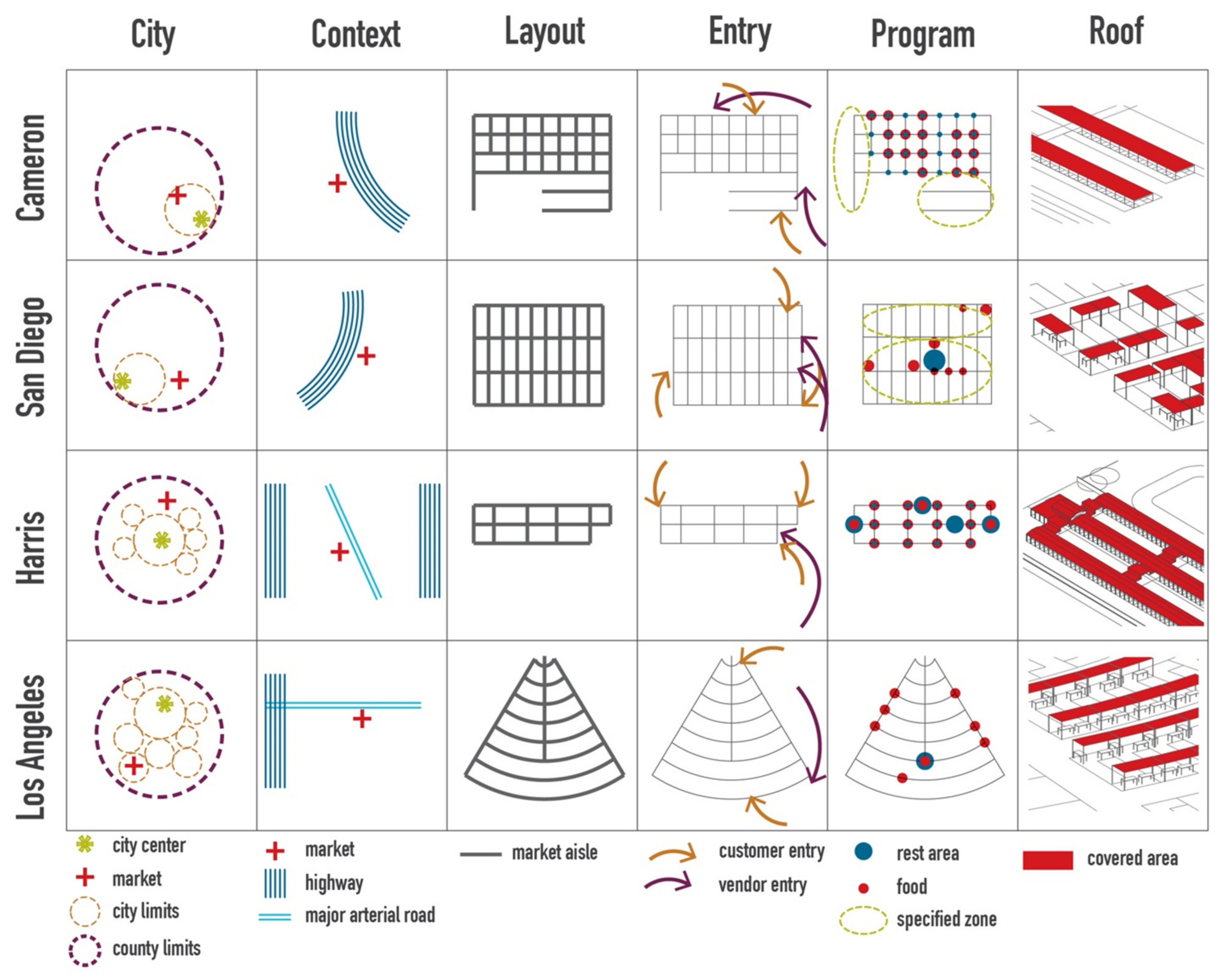

The language of place of LVM do not come together haphazardly; on the contrary, they are planned, and they share similarities in their spatial composition and ordering structures (See

Figure 1). The market layouts resemble a lattice type, which relies on the crossing of people through various path options. Access to the markets is controlled, however a sense of arrival for pedestrian requires improvement. The mixing of leisure and food is typical at all four cases; however, it is a more typical practice of the Texas markets. Weather protection through roofing structures contributes to the sense of place and each market prioritizes different levels of coverage for both vendor and customers. With the exception of the Los Angeles County market, which is open daily, the markets open only on weekends with typical hours of 7 a.m. to 6 p.m. All are located off highways and major arterial roads, and on properties ranging from 12 to 74 acres. 97% of all customers sampled arrived using their private vehicle. The markets were observed to be busy places with weekend visitors ranging from 10,000 to 50,000; each market has the capacity to host 700 to 1400 vendors, and they were found at high occupancy.

All four markets are all privately owned and operated. The four selected markets are established businesses that have been operating for thirty to forty years; the Los Angeles County market has been operating for over fifty years. They operate under an umbrella of a number of complex regulatory provisions complying with federal, state, and municipal policies. In addition to these, on site management enforce rules that guide the functioning of each market. Overall, the study shows the market management acts as a filter to checks that vendors are in compliance with the aforementioned regulations. For example, one of the ways in which the management filters are by checking that vendors entering the market have a federal tax I.D. number to ensure they are operating a registered business. Furthermore, the local municipalities have policing power of enforcement. According to the study survey, 86% of vendors stated they need a permit to operate a business at the market, and of these 97% stated they had a permit and were in compliance.

As shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2, the markets serve a predominately Latino population. While the majority of customers and vendors are immigrants, U.S. born Latinos also use the markets. The study found a more homogeneous population, predominately Mexican, on the border; while the in-land population is comprised of a broader immigrant pool including people from El Salvador, Honduras, Ecuador, and Guatemala. Additionally, LVMs attract vendors of a wide age range (See

Table 1). There is a larger portion of 18 to 29 years old at all of the selected markets except the Los Angeles County case. According to the survey, the two major metropolitan markets have vendors over the age of 60, retirees vending for additional income.

These markets service customers from a variety of income levels. A larger portion of customers in the border markets, 18% on San Diego County and 29% in Cameron County, have an income that is below the estimated

$12,000 poverty line in comparison to the in-land cases. Nevertheless, the markets attract Latinos from a variety of income levels and for the in-land markets a larger portion of customers, 45% (Los Angeles County) and 33% (Harris County), have incomes higher than

$40,000 per year as seen in

Table 2. The study found that over 50% of customers in the California cases have been coming to the selected markets for over ten years. Customers typically visit one weekend per month, during an average of one to six months out of the year. Market visits are most frequent on Sundays; some vendors speculate families like to visit the markets after church. Harris County customers are an exception, with 75% of the sample stating they typically visit the market both Saturdays and Sundays. LVM provide income opportunities for a predominantly low-income vendor population. This study found 23% of the vendors are below the national poverty line, and 78% have a per capita income of

$40,000 or less as seen in

Table 1. The economic dependence by vendors at the market is reinforced by 61% of the sample stating that vending at the market is their primary source of income.

The length that vendors have been operating at the markets indicates stories of success. For example, 35% of vendors in the Los Angeles County market have been operating for ten or more years (See

Table 1), a survival rate on par to national statistics. About one third of new businesses survive ten years or more years. In some cases, there were businesses that exceeded the ten-year threshold. At the Los Angeles County market, the study interviewed a vendor that has been operating his business for 32 years. Vending at the market has been his primary source of income since losing his job in 1990 outside the market. Many times, operational costs from leasing a commercial space are a reason for why businesses fail. However, renting a vendor booth is affordable making it easier to sustain a business at the market. The daily rental fee for a standard stall ranges among the markets:

$15 at the two border markets,

$24 at the Harris County market, and

$58 at the Los Angeles County market.

3.5.1. Risk of Redevelopment

A critique of Smart Growth planning is that ‘planning with markets’ presents a serious restriction on local governments to serve diverse community interests and to pursue social equity objectives [

36]. LVM present an insight to the disconnect of between sustainability and planning through an exploration of their risk of redevelopment. The greatest risk is the possibility of closure due to property redevelopment, as owners potentially await the right economic conditions to sell their property. As supported by the literature on flea markets a swap meets [

23,

26], the study found the case studies at risk of redevelopment. The markets have been family owned and operated businesses for thirty to fifty years, making their operation precarious; operating in the private sector means they are not publicly controlled and thus have the potential to disappear as institutions when their owners give in to property market pressures and sell. Each of the four markets is zoned for commercial or industrial uses and all four are surrounded by commercial, industrial, and single-family residential land uses. In addition to these uses, the San Diego County market is also surrounded by vacant, undeveloped land. While they may have been at the edge of the city in their inception, today the cities have grown beyond the sites of the markets. The markets are off a major thoroughfare or highway and occupy properties with few or no improvements.

Table 3 shows a breakdown of the case study market areas, appraised property value, and improvement value. The physical improvements at each market are associated with enclosed permanent buildings, which for most have little value compared to the land. Although the markets vary in scale, their appraised values are all in the millions, making it quite clear that they are a financial asset to the city and region. Looking at the per unit value, and consequential property taxes, the Los Angeles County market, in particular, could be under great pressure to sell.

The study found evidence of potential redevelopment offers in the two selected border counties, San Diego and Cameron County. Private developers had approached the market landowners and made offers to acquire the land for redevelopment. However, neither of the properties has been sold to date. Beginning in San Diego County, one family has owned the San Diego County market for nearly five decades. This same family also own two other swap meets in the county including one of the preliminary market sites for this study. In 2009, the property owner partnered with a Sudberry Properties to redevelop a 26-acre market site into a 270,000 square feet retail and commercial center with a Lowes Home Improvement store to be their anchor tenant [

57]. The site was noted as a “prime location” [

57], as it is two miles from the San Diego Bay front and 8 miles from Downtown San Diego. The development project was stalled in the negotiation phase between the property owner and the developing company, and a planning application has not been made to this date. The City Council and City Manager’s Office both supported the site redevelopment as part of their “aggressive economic development strategy” [

58]. Furthermore, at a city’s strategic planning meeting for their 2011 General Plan, the city manager stated that building a Lowes Home Improvement store on the National City Swap Meet site would bring 200 jobs to the city [

58]. Counter to this figure, the market has the capacity to host 400 small owners every weekend. A second case study earmarked for redevelopment is the Cameron County case study market. According to the City of Brownsville’s Planning Department, the property owners of the Cameron County market case study have been approached on several occasions to sell their 74-acre land to the Texas based grocery store, HEB [

59]. Although HEB’s bids to acquire the property have been unsuccessful, the potential for redevelopment remains, as does the vulnerability of the market’s future operation.

The study found that in some cases planners’ views of LVM aligned with the way the literature has prioritized farmers markets and not flea markets. For example, from interviews with city officials in Cameron County, a planner stated, “[Planners] provide free tables and tents for the local farmers market, but when it comes to the flea market, our role is simply to enforce public health and safety codes.” Conversations during the focus group sessions in Cameron County also revealed vendors’ stated need for support from city planning. Vendors expressed concerns for fees applied by the Public Health Department for food permitting. For example, according to a vendor a six-month operating permit can cost up to $1200. Lowering this fee would help support the survival of micro businesses at the market. Another critique by vendors of the city’s regulatory provisions for businesses was that the city “demands too much.” This critique was prevalent amongst market vendors operating food businesses. However, an assessment of this is that strict food regulations are necessary for health and safety reasons. Nevertheless, vendors stated that it should be easier to get through the permitting process to run and operate a food related business at the market. For example, health code standards from the city require vendors with older food trucks to upgrade their equipment. Vendors suggested that equipment upgrading be granted a flexible window to make required changes for compliance. Permit denials place a larger monetary burden on the vendors, so being flexible with them to be sure they become compliant under one permit application could be a financial support to the vendors.

3.5.2. LVM Lack Accessibility

The study spatial analysis showed that the selected case studies lack accessibility for pedestrian. Infrastructure impacts both the physical connections, and the character of spaces linking the market to its context. Political jurisdictions impact the public transit and infrastructure improvement project process. Looking at the four cases, the Harris and San Diego County case studies fall under county jurisdiction, whereas the Cameron and Los Angeles County locations are governed by city jurisdiction. This is important as a city usually has stricter ordinances than a county, in addition to there being a difference in potential resource availability for markets and business owners.

The San Diego County market, located within county jurisdiction, is not directly accessible via public transit. On the other hand, the Los Angeles County market, an example of an urban case, that can be accessed via public transit a few blocks away, but the market itself remains inaccessible to pedestrians. Customers park on the market grounds in designated parking lots north and south of the vending area. The immediate market grounds have the capacity to park 600 vehicles on the visitor’s parking lot. When the parking lot is at capacity, overflow vehicles must park at the El Camino College parking lot located a quarter mile from the market grounds and utilize a free shuttle service provided by the market management (See

Figure 2). Repurposed city buses are used as shuttles to drive people from the parking lot to the market. On site security guards, staffed by the management, direct the loading and offloading of people at the parking lot and at the market entrance. Customer walk-ins are not allowed (See

Figure 3); customers can only enter the market by driving into the market or by using the shuttle (See

Figure 4). The lack of pedestrian access to customers presented challenges during the fieldwork; being turned away and asked to walk from the market back to the shuttle pickup was disorienting, and potentially dangerous as both Redondo Beach Boulevard and Crenshaw Boulevard are highly trafficked roads.

3.5.3. Reinforcement through Improvement Districts

The Harris County market is part of the Airline Improvement District enacted by the State Legislature in 2005. The district is in an unincorporated area of Harris County; it was created as a means to supplement the county’s public funding capacity [

60]. The district generates revenue through a 1% retail sales tax within the district boundary; the sales tax revenues have been used to fund the addition of sidewalks and pedestrian crossings along what the district has called “Market Mile” on Airline Drive (See

Figure 5). The Harris County Market is one of five Latino markets along Airline Drive. The community recognized the need to support their local businesses, and the Latino markets were recognized as anchors in the capital generation of the business corridor. Airline Drive is a heavily trafficked five-lane road, and the need to calm the traffic to improve walkability and access to the market was identified by the community [

60]. Following this study, the improvement district funded the building of new sidewalks and pedestrian light signals for safe crossing between the markets (See

Figure 6). The street improvement project also included the addition of a fenced median along Airline Drive to ensure that pedestrians only cross at the designated crossings. Addressing the need to calm traffic along Airline Drive, City of Houston reduced the street limit of this major thoroughfare to 35 mph (City of Houston Ordinance No. 2009–1023, 2009). The Los Angeles County market currently uses the El Camino College parking lot to shuttle customers to and from the market. Customers are not allowed to walk to the market; there is need to improve the pedestrian infrastructure surrounding the market and increase walkability for local residents.

4. Conclusions

Using four case studies to explore how urban planning policies have impacted Latino vendor markets (LVM), this paper provides lessons that could be adapted by cities in order to support these markets as increasingly significant community places. Lessons from the place analysis show that the markets are part of an emerging city landscape, not about centrality, but a potential new nexus in U.S. cities. The location of the selected Latino markets is a product of U.S. development patterns of the 20th century; they anchor edges of major transit infrastructure and are auto dominant. The four case studies host a diverse demographic of vendors and customers of a wide age range and incomes. Nevertheless, the majority of both customers and vendors are low-income with earnings less than $24,000 per year. Many of the people that are serviced by the market keep coming back as the survey showed a large portion of vendors and customers have been visiting the markets for over ten years. As cities push to advance social equity objectives, planners should see LVMs are important places in that bring together a marginalized population. The market profile analysis showed that LVM are at risk of potential redevelopment; they lack accessibility and perpetuate car dependence; and yet there are opportunities to support LVM through planning tools such as improvement districts. Planning policy should encompass physical frameworks, in addition to social, institutional and cultural infrastructure that sustains the city. Planning offers a set of tools through strategies, designs and regulations that serve communities broadly.

The study examined the implications of potential redevelopment scenarios for the sites, possible closure of the market due to competing private interests and addresses these risks in the context of potential redevelopment schedule explored for some of the selected case studies. What planning lacks is a tool or language to protect these types of environments that operate within the private sector. Economic development planner could learn from planning working in areas of housing and explore mechanism such as community land trusts (CLTs) that have the potential to protect key and vulnerable assets within the community over time. CLT is a model that effectively creates community control of property used primarily for affordable housing and community development [

62]. A key component of CLTs is the element of stewardship, which ensures that their properties provide lasting benefits to the community and that residents are engaged and supported beyond sale or occupancy of their home [

62]. Protecting low-income and marginalized Latinos that operate micro-businesses at these markets would require a similar approach to stewardship to ensure the benefits provided by LVMs are long lasting. Cities could engage in public-private partnerships between the local governments and private property owners as a way to support the communities that LVMs host.

The study found that LVM could more accessible via public transit. Communities should plan for equitable distribution of public services, including transportation access [

37,

63,

64]. Cities could, therefore, support the building of markets as more robust city places by improving access. The long commute times, and length of walking required between the transit stops and the market is problematic for a number of reasons. Accessing the market during harsh climatic conditions could limit the days which family without a personal vehicle could travel to the market comfortably. Mothers with young children would find it challenging to leave the market with bulky items and bags of groceries; walking along side of a highway would be dangerous given the lack of pedestrian sidewalks to the market. The study showed through the Los Angeles County market case study how prioritizing automobile access marginalized the pedestrian experience. To improve the pedestrian experience, the Los Angeles County market could learn from the Harris County market’s model of using improvement districts to upgrade pedestrian infrastructure and increase walkability between businesses.

Improvement districts are a type of public-private partnership that align with the increasing trend towards high quality urban infrastructure as a strategy to stimulate economic growth and create jobs, remediate environmental problems, and promote social equity [

65]. Improvement districts fund a variety of services for the betterment of public environments [

66]. In California they are referred to as Business Improvement Districts (BID), while in Texas they are Public Improvement Districts (PID). Although their names differ slightly, their basic methods of operation are similar. The designation of improvement districts occurred in the 1980s in both California and Texas. Improvement districts are considered to be an effective tool to enhance both the business and physical environment of retailing; they also allow private business owners to engage in the district revitalization process [

67]. In Texas, improvement districts typically fund landscaping, district lighting, sidewalk improvements, art installations, pedestrian crossings, transportation facilities, and water and wastewater drainage improvements among others [

68]. Texas and California allow cities and counties to enact improvement districts to levy annual assessments of the tax base within a defined district boundary for the benefit of the businesses in the area. To create a BID, owners of 50 percent of the appraised value of taxable property within the proposed district must agree to the creation of the improvement district [

68].

Improvement districts are thus a possible regulatory funding mechanism to improve public easements in recommending potential market business districts, and a wider use of this tool could allow for planners to forecast the reinforcement of LVM and its surrounding areas. Improvement districts are a planning tool that mutually support private and public interests. In the case of markets, private property owners would benefit from the improved access that infrastructure projects could bring, and local municipalities are relieved from the economic burden of funding public works projects on a limited budget. The Harris County market presents lessons for markets that operate in similar contexts and that are adjacent to other businesses. The Market Mile created by the Airline Improvement District allowed for market visitors to cross safely between the markets and local businesses flanking the road. If other markets developed improvement districts with surrounding partners, the improved infrastructure would increase access and porosity in the urban realm.

As planning continues its shifts towards implementing sustainability and equity focused policies [

36,

37], the reality is that equity is often de-emphasized in practice [

37]. Fundamentally, equity is about distributing public resources in favor of those who are less well-off, expand choice, and increase agency [

37,

69]. Planning should prioritize the development of plans that identify vulnerable people and geographic areas and ensure equitable protection from hazards and equitable distribution of amenities [

37,

39]. LVM are important places in the emerging American city landscape. In considering the future of the 21st century U.S. city, it is important that key components of American city culture be valued and understood. LVMs are a significant city places for many Latinos. Disparities across cities can be explained by examining investment and financial priorities on the part of a city. Economic development strategies targeting large scale investments and businesses on the part of the city government continue to be a common practice. For example, government’s investment on airports and financial support to sports and private commercial entities are seen as an important mechanism in support of a local economy. However, the study found little evidence that LVM receive any form of protection, or fiscal support in these case studies. Planning must take hold of a central responsibility to plan for all people, to support all economic causes, perhaps particularly microbusinesses, to help daily life, and at the same time promote careful and incremental improvement of their city’s amenity and fabric.

This research applied a case study methodology and therefore does not present findings that are statistically generalizable about a wider population group; the purpose was to understand the case not to generalize [

43]. While the previous discussion focuses on lessons for city planning officials in the selected cities; cities with LVMs of similar profile can learn from these findings as planners consider ways to support markets and the Latino community. Further research would be required for context-specific knowledge when addressing the needs of other markets.