1. Introduction

The aim of this work is to identify the social constraints on the preservation and sustainable development of traditional crafts in a developed society and to propose a sociological model of not only the situation of craftsmen, but also the potential consumers of goods produced by craftsmen using traditional techniques and designs. We rely on data from one country (Poland), but we show how the proposed model can be adapted to the local situations of other countries and we indicate the possibilities of further research and applications.

Creating a sociological model implies the use of a qualitative approach of humanistic sociology and social anthropology (although we also use quantitative data), in which we adapt to modern requirements the classic approach of the renowned Polish scholar Stefan Czarnowski, who belonged to the Durkheim school of thought [

1]. We argue that effective activities aimed at preserving and developing traditional crafts, skills, and products must take into account changes in the social environment of the craftsman, including changes in the potential consumer, a change in the meaning of products from purely instrumental to autotelic motivations related to the pro-ecological approach, local and national identity, positive valuation of cultural diversity, and combining the preservation of intangible heritage and tourism [

2].

We stress that the preservation of traditional crafts cannot be understood as the passive conservation of the “remains of the past” but is an active and, above all, reflexive agency.

In an article published in 2018, Yang et al. indicated several challenges and constraints to the handicraft industry in developing countries [

3]. Many of them are also important in developed countries. They stress the need to collect sufficient data on the handicrafts, highlighting the problem of finding appropriate metrics for activities that are often informal. They point to the challenge of industrialization and mass production for the craftsmen caused by the replacement of the traditional handicrafts by machine-made products and the related problem of the unwillingness of younger generations to continue to work in traditional professions. These kinds of problems also occur in developed countries. Additionally, they note the lack of availability of basic infrastructure, lack of innovation and technology, lack of education and training facilities, and lack of financial resources for craftsmen. The latter group of factors is often different in developed countries, although they also have an impact on the situation of craftsmen. In this work, we use the concepts of traditional craftsmanship and tangible and intangible cultural heritage in the same way as our predecessors quoted above [

2,

3].

In our study, we try not only to show the differences between the situations of craftsmen in developed and developing countries, but also to take the next step in understanding the problems identified by our predecessors by analysing deeper structural and functional determinants visible in changing societies. The constraints on the preservation of traditional crafts do not constitute one permanent list of factors that can be simply enumerated. They emerge from the structural context, the understanding of which may help formulate recommendations and policies regarding the protection of cultural heritage and at the same time may facilitate the formulation of adequate definitions of traditional technologies, which is a frequently indicated problem in the case of intangible heritage. Moreover, constraints in one context may become an opportunity for sustainable development in another.

Using the approach of Czarnowski, we created a model consisting of four levels of analysis for the problem of change and preservation of traditional technologies, accompanied by the “0” level, which is the situation of the loss of a given tradition since, as we argue, we can speak of preservation of cultural heritage not only when the given object or work is preserved, but also when the methods of production and/or use are preserved at least in a form where a return to them in the future is possible. The analysis at level 1 shows the minimum level of preservation of traditional technology, in which it is reduced only to a symbolic sphere (e.g., ritual use). It can be assumed that items directly related to the symbolic layer of culture are not subject to the structural conditions that are visible in areas related to production and the economy. Level 2 examines the structural conditions for the duration, change, and diversification of technology and the economic and social factors influencing the use of traditional or new technologies. Level 3 discusses the functional contexts of using traditional technologies. We examine the problem of the context of using a given technology and we conclude that the key to solving the problem seems to be the creation of conditions for the cultivation of traditional crafts and skills not only as professional work but rather as an “additional” activity supporting other forms of earning and transferring traditional skills from the sphere of purely professional work to the sphere of free time, hobbies, or self-realization for people making conscious life choices, not necessarily at a young age. Level 4 raises the issue of non-economic motivations for the preservation and sustainable development of traditional crafts. In the case of fully autotelic motivations for preserving cultural traditions or motivations related to cultural or national identity, the most important thing is (1) the complete preservation of a given habit and its internal coherence, not its external compliance with the social structure or original functions, or (2) the emphasis of the “familiarity” of a given habit, skill, or object, regardless of the economic, ergonomic, or ecological calculations.

We argue that the preservation of cultural heritage, especially in the form of traditional crafts and technologies, should not be understood in the dichotomic win or lose categories but can be seen at several levels of preservation and change as a continuum of possibilities, which are both a challenge and an opportunity to preserve not only tangible heritage but also intangible cultural heritage.

2. Theoretical Model of Technological Change and the Preservation of Traditional Crafts

Research on changes in traditional crafts has a long tradition in Poland. Their strengths lie in combining considerations of the preservation of traditional crafts and skills with those of technological change. The key figure here is Stefan Czarnowski, a Polish sociologist, folklorist, and cultural historian (1879–1937), who in his classic work “Kultura” (Culture) [

4] deals with the issue of adopting new inventions, tools, and technological solutions and the resistance to changing traditional technologies. As Czarnowski wrote in Polish, his works are little known outside of Poland, although he proposes a very deep and creative approach to the issues of interest to us here, and which we are currently trying to develop and apply to the problem of the preservation of traditional crafts.

From today’s point of view, the weakness of Czarnowski’s deliberations could be seen in his focus on empirical considerations of examples that he considered to be self-evident and not in need of an abstract formulation. His inductive method, due to the passage of time and successive technological changes that have taken place since the time in which he wrote his works, may leave the impression that his examples and explanations sometimes have only historical significance. However, if we translate his considerations into an abstract language and apply them to modern technologies, as is our goal here, and use them to analyse the problems of preserving traditional skills (crafts), we will see that they were precursors to and as profound as the analyses of later, more famous researchers such as Marvin Harris [

5] or, more recently, Tim Dant [

6].

Czarnowski conducts his considerations from the perspective of technological development. His main question in this regard is why certain solutions are not adopted, even if they are more effective and labour-saving. However, his work contributes significantly to the understanding of the problem of the preservation and sustainable development of traditional skills and crafts. The problem of adopting new technologies is the “other side of the coin” of preserving traditional crafts and forms of production. The difference is the evaluation of traditional techniques and methods in favour of new ones, most often coming from a different culture. In this understanding of the problem, we can use, after adaptation, all anthropological knowledge regarding cultural contact (especially the achievements of diffusionism in anthropology) to analyse the problem of preserving cultural heritage [

7].

According to Czarnowski, to understand the process of adopting new technology in a given culture, it is not enough to use the categories of classical economics, i.e., not every solution that will save effort or increase the possibility of exchange will be adopted. In his opinion, the lack of capital to introduce a new technology or the reluctance to lose already invested capital is not a sufficient explanation either. He points to several factors of different kinds that contribute to the lack of acceptance of a given technical solution. Czarnowski’s classic considerations can now be systematized by indicating several levels that are important in the change and preservation of traditional skills and the adoption of new technologies.

2.1. Level 0. Object, Use, Production

The starting point is a definition explaining what we can understand by technological borrowing. An inversion of this definition gives us the basis to establish what we can understand by the preservation of traditional crafts, skills, and technologies. Czarnowski points out that “One can speak of technical borrowing only when not only the object is accepted, but also the way it is used” [

4]. He gives a number of examples from traditional cultures where only the object is taken over, but the way it is used is not. In such cases, the item loses its utility value completely, most often becoming only a decoration. The reformulation of this statement in the case of preservation of cultural heritage may take the form of a statement that we can speak of preservation of cultural heritage when not only the given object or work is preserved but also when the methods of production and/or use are preserved, at least in a form where they can possibly be returned to in the future.

Nowadays, we deal with the preservation of objects without traditional use or production methods in at least three contexts. First, we can look at upcycling, i.e., the use of old objects in a decorative function or as a form to create objects with a completely different use. As a rule, upcycling implies reworking to obtain an item of greater value than the original one. This type of treatment can be exemplified by the use of old shoes as flowerpots or the use of the base of old Singer sewing machines as table structures, which is popular in Poland. Such a modification, however, deprives the original object, often irreversibly, of its original function. From the old machine, only the frame remains, and the mechanism is most often thrown away. In this context, a question may be asked of whether such a modification still falls within the category of the preservation of the object (not to mention the ways of using it) if the object is no longer fit for its original purpose. In its extreme form, it may be treated as only the sham preservation of it.

The next form of apparent preservation of old objects is treating them as museum exhibits. In this case, we are not dealing with the processing of a given item, but with a complete change in the way the item is used. Its preservation, not its use, is of paramount importance. In some cases, however, securing an item for exhibition purposes requires depriving it of its functionality, where the safety of visitors and care for the preservation of exhibits push the museum to devoid the objects of their utility.

The third situation is keeping objects unchanged but treating them only as decorations that have no function other than an aesthetic purpose, with possible additional reference to the style or times from which the item originates, for example, the use of old tools, utensils, or everyday objects to achieve a rustic style or the use of buddha statues to achieve an oriental effect in a given space. Such use of objects, deprived of their old context and, above all, of their old functions, cannot be regarded as adequately preserved tradition or adoption of a new cultural element.

Summing up the argument so far, we do not keep traditional crafts as such, we only keep the memory of them. At this point, a gap in Czarnowski’s approach should be emphasized. Czarnowski, dealing with the introduction of new technologies, most often originating from cultures other than the analysed cultures, did not consider directly who the producer of a given item was and how a given item was produced. Such an omission is not significant when we consider the introduction of industrial products, “new technologies”, which, in their finished form, are imported and introduced in new social and cultural conditions. The question of the manufacturer and the methods of production, however, starts to be of significant importance when we consider traditional crafts. In this case, the problem appears in the form of replicas that are supposed to look like traditional items but are created by industrial methods that are often unrelated to their traditional places and methods of production.

In a related art sphere, this is expressed in the difference between an original painting or sculptural work and its industrial reproductions. However, such situations should be distinguished from the process of being inspired by a work of art by folk artists.

In the traditional crafts, another problem arises with innovation. When using traditional techniques and traditional materials, the craftsman produces new products, such as a smartphone holder. It should be remembered that traditional technologies also had dynamic aspects and were subject to external influences and internal innovations, adjusting them to changing social situations. Additionally, not all elements of traditional technologies were produced “on the spot” and black-and-white categories should not be used here. On the other hand, traditional craftsmen are accused of a lack of innovation, but innovation is often treated as a denial of tradition. For a craftsman, it may be safer to limit production only to well-known, traditional patterns and objects. The use of modern tools or chemicals at certain stages of production may also be debatable, although no one requires traditional craftsmen to light their workshops with candles.

2.2. Level 1. Limited Assimilation of Technology and Symbolic Meaning

Czarnowski largely focused on developing new tools, i.e., items that were used to produce other items. He analyses, inter alia, situations when a new technology is so much more effective than the previous technology that its adoption seems inevitable. He gives an old example of the replacement of stone and shell axes used by Hawaiians by steel axes imported from Europe and points out that in this case we are not dealing with completely new technology, but with modernized technology, and only in terms of a more durable, more effective material from which the axe is made while preserving the way of use because the steel and stone axe is held in the hand and used in practically the same way. The limitation we can observe here is the ritual sphere. Traditional axes “started work”; they were used for the first blows, and the whole ritual layer was focused on them, although almost all the work was done by more modern tools. Czarnowski’s example is a good illustration of the minimum level of preservation of traditional technology in which it is reduced only to a symbolic sphere, allowing at the same time the maintenance of the unchanged forms of ritual associated with a given activity. In modern reality, one can find many examples of a similar reduction of traditional technologies (not only tools) to the symbolic sphere (see below).

On the other hand, Czarnowski emphasizes that it is quite easy to adopt new inventions that are not related to the most important spheres of a given culture from an economic point of view. Objects for play, decorations, or objects considered to be signs of dignity are more easily accepted than objects directly related to the economic basis of existence. Interestingly, it seems that in the case of the preservation of old traditions, this regularity can be directly transferred without significant modifications. It can be assumed that such items are directly related to the symbolic layer of culture and that they are not subject to the structural conditions that are visible in the areas related to production and economy. In the case of decorations, items for fun or entertainment, and items that are the basis for building prestige, we can assume that they are complementary to other items that can perform the same functions. Lei Meng rightly notes that contemporary cultural and creative products have gone through the process of gradually detaching from traditional arts and crafts to seeking expression of personality, from seeking market integration to transforming into creative products [

8]. Nevertheless, there is still room for traditional designs as well. The fashion for “folk”, traditional decorative elements do not have to exclude the functionality or creativity of a given item or piece of clothing, although it should be noted that there is a significant difference between a fully traditional garment (production method, materials, methods of use) and elements only stylized, referring to tradition only at the design level, e.g., a t-shirt with an ethnic pattern or a plastic doll dressed in a folk costume. However, traditional toys, for example, that are made of wood, traditional tools for sports, such as bows, or traditional technologies used in the construction of boats, yachts, or houses, which are a sign of prestige, can function alongside similar items made with the help of modern technologies. In this context, attention can be paid, for example, to the renaissance of vinyl records, which were almost completely replaced by more modern forms of sound reproduction. In the categories proposed by Czarnowski, one could speak of the diversifying role of cultural relics which, losing their instrumental value, acquire symbolic values.

Interestingly, the greater the degree of function change, the more important the traditional way of making a given item becomes, often defined as its “originality”, and less important is its use-value, understood as the technical advancement, but also its low price. In the case of the so-called Veblenian goods, we can even see the opposite relationship, that is, the higher price, the more desirable the goods. It seems that in this type of mechanism there is a great chance for the preservation and sustainable development of traditional crafts. Researchers have repeatedly pointed out that traditional and handicraft products are losing the price competition with industrial products. The above considerations indicate, however, that such a loss results from the fact that they are involved in the “wrong game”; they are incorrectly positioned. It is one of the conclusions of Zhu et al.: “Supportive policies such as platform building, organizational exchange, holding competitions, award schemes, and expanding sales channels can all significantly promote price rises among the handicraft products of traditional craftsmen and improve manufacturing skills” [

2]. Products that can be emphasized as being environmentally friendly, made following the principles of sustainable development, as well as products that meet the criteria of vegan or “preservative-free” in the case of food products, can be successfully sold at higher prices than standard industrial products.

2.3. Level 2. Structural Conditions for the Duration, Change, and Diversification of Technology

One of the key distinctions introduced by Czarnowski is the distinction between technology change and development within the same technology related to the introduction of better tools while maintaining the main assumptions of a given technology. Using the example of agricultural techniques, he states that the first process (change of technology) may be illustrated by the transition from digging to plough-based coupler farming. In this regard, the cultivation of the land in coupler farming is quite different from digging regardless of the type of force that pulls the plough. The transition from a pickaxe to a hoe or, in the case of plough farming, from a horse-drawn plough to tractors, is an example of the second type of situation, that is, the improvement of a given technology.

Establishing an unambiguous boundary between new technology and the improvement of existing technologies may, of course, be debatable in specific empirical cases, but this distinction turns out to be important from the point of view of limitations in the introduction of new technologies, which Czarnowski points to, and to questions of the preservation of traditional technologies. He notices that in many cases the new technology does not fully replace the earlier technologies, but only creates new divisions or fields of application characteristics for a given technology.

Using the example of a plough and digging, the former did not replace the earlier technologies in the case of small areas or in cases where the use of more mechanical methods of production would reduce the efficiency of crops. In this context, Czarnowski points to two other types of factors: economic and socio-cultural. In the case of economic factors, we are dealing not only with the one-time cost of purchasing “new technology”, but also with issues related to the further maintenance of a given technology, such as the issue of access to a specialist who could repair the equipment, purchase of fuel, or spare parts. Let us note here that complicated tools, because of their price, may turn out to be unprofitable in the case of small-scale production or occasional use. This situation can be seen with a variety of home appliances and DIY equipment that are used sporadically. The choice of manual, not mechanical, combustion-based tools for felling trees for people who only deal with their garden or orchard is a more economical solution, and it is also a solution closer to the principles of sustainable development. In such cases, it is more effective to promote and use more developed tools within traditional technologies, and not to introduce new technologies based on the use of internal combustion or electric engines. The awareness of the challenges of environmental protection and sustainable development takes a step back in some areas of activity rationale. Traditional tools and technologies may turn out to be more economically effective when we consider the overall impact and cost of the production, transportation, use, repair, and disposal of the item on the one hand, and the health benefits of moderate exercise on the other. Resistance to new technologies once stigmatized in traditional societies can be an expression of thinking that considers a broader spectrum of factors. For example, Gajšek et al. argue that there is excellent potential in craft workplaces to increase productivity by adding current technologies while protecting the health of employees and maintaining the flexibility of decision making between manual and robotic processing [

9]. Again, the answer does not seem to be all-or-nothing. What is needed here is a reflective approach to each situation.

Economic factors are closely related to socio-cultural ones. Czarnowski focuses on examples related to gender and the division of labour within the family. He points out that individual activities are often traditionally assigned to a specific gender and resistance to new technology may be related to the need to involve, for example, men in activities that are considered typically feminine or vice versa. Another point is that many family members, including children, are involved in farm activities, and the introduction of new technologies would exclude some people from production activities. These issues seem to be less important nowadays, but on a more general level, they can be related to the issues of division of labour and the time and skills needed to perform a given activity.

New technologies are focused on the faster and effortless execution of a given activity. Reducing the production time was a great achievement of the industrial age, but the results were not equally spectacular in all circumstances. In the case of many activities performed at home, but also in the case of making original products with a small number of copies, the time saved thanks to the use of modern technologies is shrinking. A known problem here is the time not only of the actual performance of the activity but the time spent on setting up machines and devices and their subsequent cleaning and storage. Even if the actual activity is not time-consuming and is efficiently performed, additional activities may cause the overall time to perform a given activity to be longer than with the use of traditional technologies, even assuming that we have the appropriate equipment “to hand” and they do not have to be bought or rented. In many contemporary societies, various types of production and repair activities are delegated outside the household, although by using traditional, simple technologies, they could be performed independently. It is part of the known process of transition from natural consumption to market-mediated consumption [

10]. However, researchers of this problem point out that in households with limited incomes, the time gain does not balance the costs of purchasing a given product or service when a given person has a large amount of time and few financial resources [

10]. In modern market circumstances, it is one of the factors influencing the development of the DIY sector (strongly developed in Poland) or influencing the popularity of retail chains such as Ikea offering furniture prepared for self-assembly. Such products are bought because of the lower price of the final product and not for hobby reasons. For Polish consumers, price, along with quality, is still a key factor in shopping choices. A total of 74.3% of Poles primarily choose a product because of its quality, 69.2% take into account the price, and then the place of origin of the product (34%) or ecological values (22.2%) are taken into account [

11].

As part of this trend, there is considerable potential for the redevelopment of traditional technologies not only in the field of domestic durable goods production, but also in the preparation, processing, and storage of food products. Of course, the use of traditional technologies does not have to be dictated only by economic necessity but may become a conscious choice related not only to pro-ecological attitudes, but also to identity choices. It is worth noting that this approach is the most consistent with the trend of defining sustainable manufacturing practices, as they most often involve low environmental impacts, conserving energy and natural resources, or using them in a sustainable way [

12].

The issue of skills related to the use of modern and traditional technologies is not so clear-cut. It is visible in the example of Ikea furniture presented above. They are prepared in such a way as to make assembly easier for the buyer but also include detailed assembly instructions. In this case, it is not without significance that these are instructions based on well-thought-out, easy-to-understand infographics for a non-specialist and not verbal descriptions or technical drawings that require specialized skills. Many modern tools are designed to automate the performance of activities that previously required the manufacturer to have the technical knowledge and manual skills and thus facilitate the performance of a given activity, but often new technologies require more knowledge and skills than traditional technologies or at least require a different kind of knowledge and skills. Let us use the example given by Kristina Niedderer and Katherine Townsend: “For example, digital technology including 2D and 3D modelling software, CAD/CAM and rapid prototyping have influenced the ways craft practice has developed, particularly in the last decade” [

13] (p. 625). In this context, Czarnowski paid special attention to the role of habit and routine, which cause reluctance toward adopting new, often more rational, solutions, giving the example of the transition from writing with goose feathers to fountain pens and then the use of typewriting. He argued that the new solutions were accepted primarily by the younger generations who were immediately taught to write with the new tools, while the older generations maintained the existing solutions.

2.4. Level 3. Functional Contexts of Using Traditional Technologies

However, habit and routine may in many cases be only apparent explanations that do not consider the overall structure of the experienced world of a given individual or the conditions of using a given tool or object in the broader context of life activities.

Along with the distance from the basic conditions, Czarnowski’s model requires a greater degree of modification in order to explain not only the reluctance to adopt new technologies, but also the chances of the preservation and sustainable development of traditional crafts. In Czarnowski’s considerations, the analysis of the use of the reel in rural areas can be considered an experimentum crucis. He points out that the reel was adopted without problems in a situation where it was used as the basis of a market-oriented cottage production when it was the main production tool on which a person’s livelihood depended, as it was more efficient than the spindles previously used. In his analysis, he considers all the factors mentioned so far to indicate that they were not crucial in explaining the resistance to the reel in rural areas. The key factor was the inability to reconcile sitting work at the reel with the other activities of a woman working on a traditional farm, requiring constant movement and continuous breaks from a given activity to engage in another activity. The reel in rural areas could be used seasonally in the winter when the number of other duties decreased, and it could be used by certain categories of people, such as, for example, young, unmarried women who had relatively few other duties. The reel turns out to be effective in the case of market production, and its efficiency drops significantly when it is part of natural consumption, i.e., a part of production for one’s own needs, in which a large amount of thread is produced, and the degree of its standardization is not so important.

The problem of using a reel can therefore be generalized to the problem of the context of using a given technology. In the case of various projects aimed at preserving traditional crafts, it is assumed that such crafts are to potentially become a profession performed by a given person and therefore they are to become the basic source of income for which a given person is to prepare under the formal education in a specialized vocational school. A closer look at Czarnowski’s analysis, and above all the use of these categories to analyse the chances of preservation and sustainable development of traditional crafts, clearly shows why such activities often have not been very successful in terms of the final products obtained, economic efficiency, and the scale of demand for traditional goods, which results in the necessity of non-market support for the production of traditional products or condemning them only to niche applications, and finally to losing unequal competition with mass-produced goods, where the real production costs and negative environmental consequences are hidden or divided into a large number of reproducible and standard copies.

The key to solving the problem seems to be the creation of conditions for the cultivation of traditional crafts and skills not only and not so much as professional work but rather as an “additional” activity supporting other forms of earning and transferring traditional skills from the sphere of purely professional work to the sphere of free time, hobby, or self-realization for people making conscious life choices, not necessarily at a young age. This approach seems to be in line with what Autio points out that an appropriate solution would be to enable students to acquire the basic skills required in everyday situations in both traditional craftsmanship and technology education [

14].

It is necessary to consider not only situations when it comes to the market sale of manufactured goods but also production for one’s own needs and non-economic motivations for taking up the given activities.

2.5. Level 4. Non-Economic Motivations for the Preservation and Sustainable Development of Traditional Crafts

Czarnowski indicates that technological changes mean that some people lose their jobs. This illustrates the reluctance to introduce a more modern type of plough in French Brittany in the nineteenth century, which resulted in many agricultural workers remaining unemployed and having to seek employment outside agriculture. This, in turn, entailed not only a change in the current professional structure, but also a change in the social structure and the prestige of the farm owner as an employer. Czarnowski was primarily concerned with how a given technology influences the social structure—does it perpetuate it or change it? In this regard, he points out that it is easier to accept technologies that fit into the existing social structure, into already existing social inequalities, often maintaining and strengthening them through the “elite escape” mechanism. The situation is different in the case of “revolutionary” technologies, which will force social change, or at least stimulate it. They will be received unfavourably by the current elite but may be positively received by the disadvantaged.

Nowadays, we can notice successive phases of changes that cause rural areas to not only be suppliers of agricultural products but also to become areas for spending free time, relaxing (which is related to the development of agritourism), and a place for migration from urban areas of both people who (thanks to the development of telecommunications technologies) can perform their professional duties remotely and people who want to change their lifestyle and are starting to be interested in traditional technologies for autotelic, cultural, and/or health and ecology reasons.

If we are talking about “revolutions”, we can mention Thomas Khun and his analysis of scientific revolutions [

15]. Perhaps there is a similar regularity in science and technology. It should be noted, however, that one form of “revolution” may be a return to old patterns (such as the Renaissance). Nowadays, perhaps, traditional technologies and the old way of life (slow life) are a weapon in the revolution related to the ecological trend. Therefore, in the case of interest in traditional technologies, we can distinguish at level 4 the search for solutions in traditional technologies that are environmentally friendly and “sustainable”. This new motivation or “new” value changes the picture (calculation) of factors from previous levels. We add an additional factor influencing the overall assessment, which, however, does not always have to be in favour of traditional technologies, which is visible in the case of using a fireplace or cooking on a fire or a barbeque, and may encourage a selective approach to tradition.

The situation is different in the case of fully autotelic motivations to preserve cultural traditions or motivations related to cultural or national identity. Here, the most important thing is (1) the complete preservation of a given habit, its internal coherence, not external compliance with the social structure or original functions, or (2) emphasizing the “familiarity” of a given habit, skill, or object, regardless of the economic, ergonomic, or ecological calculation. Note that in the latter situation (emphasizing identity), traditional technologies are also treated instrumentally, only the level of this instrumentality changes from pragmatic to symbolic instrumentality—similar to level 1.

One more context is possible here, which is well known and present in the sociology of consumption [

16]. It is a tension between fashion (changeability, the search for constant novelties) proper to modernity and the “patina”, that is, emphasizing the continuity and old roots, which were characteristic of the old nobility, for people who wanted to emphasize their unique roots. Even if today it is no longer necessary to emphasize “nobility”, when we begin to “create an identity”, for example, a national one, a reference to “patina” seems a probable solution. Thus, it will not be a lazy routine or an inability to adapt to the changing world, but the choice of a “cultural pattern” that will emphasize our uniqueness and will emphasize the continuity of certain customs. We will not eat with chopsticks in Europe, not because we cannot use them or because they are inconvenient (when we eat sushi, we accept them), but because they are “not ours”. Eating with a fork and knife, the whole of “savoir vivre” refers not so much to the practical benefits (which are sometimes deceptive and often function as ex post rationalizations), but to our cultural perceptions, to the patterns of how a person is supposed to behave

3. Examples Complementing the Theoretical Model

3.1. Level 0. Object, Use, Production

The essence of keeping an object that is a product of traditional craftsmanship or technology at level 0 is to preserve only its material form without maintaining the methods of use or production in accordance with tradition. However, if an item is used in a new way, it loses its original use-value, which is the defining feature of preservation. This approach is developing quite intensively thanks to the development of new economic models related to the pursuit of the circular economy, including the use of the approach related to the aforementioned upcycling, following the guiding principle of creating a regenerative system that, at the level of long-lasting design, will lead to minimizing or even completely reducing waste [

17]. In this context, it is worth emphasizing the definition of upcycling, which says that it is defined “as transforming waste(d) products, parts or materials into secondary resources as products, parts or materials of at least equal and preferably better technical, economical and societal quality, without burdening people and the environment with hazardous and harmful substances add value and reduce the use of virgin materials in the process” [

18] (p. 4). The essence of this definition is not the preservation of the original item but its transformation. The object itself is not important here but the materials from which it is made.

There are more and more companies on the market that, acting following the principles of sustainable development and ecological responsibility, adopt the creative transformation of other companies’ “waste” as the foundation of their activities. Examples of such activities are start-ups distinguished in the report “Start-ups of positive impact” published in 2019 by the Kozminski Business Hub. Among the awarded companies was, for example, the Deko-eko company, which describes its activities as follows: “We propose an innovative upcycling platform which will completely change the way you think about waste. We turn waste into profit by facilitating the highest possible jump in value—from zero to a market-ready product” [

19]. Another example is the Rec.on brand, which “gives recovered auto parts a new chance to shine again. Using a unique upcycling process, we transform used, unwanted parts into new, high-quality, functional designs, adding style and an industrial aesthetic to any interior” [

20]. These are examples showing what could be considered a creative activity related to the use of old or used objects. It becomes a new approach related to running a business based on the principles of sustainable development but not aimed at preserving cultural heritage. One can refer in this context to an understanding of sustainability from the perspective of Orr, who called it “the arts of longevity” [

21]. Former items are treated here as rubbish or unwanted parts that would otherwise end up in a landfill or would be processed only at the level of the materials from which they were made.

The above examples clearly show that at this level we are not dealing with the preservation of traditional technologies, neither in terms of tangible heritage nor intangible cultural heritage, even though this action should certainly be assessed positively when we consider sustainable growth and ecological responsibility. It should be noted that initiatives such as Rec.om are based on industrial products taking them into a new sphere.

In the context of our considerations, there is no need for a detailed analysis of museum exhibitions containing exhibitions of traditional crafts. We can only pay attention to the fact that the most common place where we can meet traditional crafts are open-air museums, which are scattered throughout Poland, presenting Polish folk art. Many of them try to go beyond the mere preservation of traditional craftsmanship by organizing shows for visitors during which you can see the work of a blacksmith, wicker, or potter. A good example is the Museum of the Mazovian Countryside in Sierpc (Muzeum Wsi Mazowieckiej w Sierpcu) [

22]. In recent years, this type of activity has been hampered by the COVID-19 epidemic, but in 2019 one of the co-authors had the opportunity to observe an event organized by the museum during public holidays in Poland. During such events, visitors to the museum have the opportunity not only to see traditional objects through safety glass but also to touch objects and try, for instance, to create a clay vessel by themselves, play with traditional wooden toys, and try traditional food—as opposed to seeing an artificial replica of it placed on a table in a traditional hut, which can only be viewed through a window. Such an event is an attempt to go beyond level 0, and we can see that this need is also seen by the creators of museum exhibitions. However, most museums are dominated by a static presentation of items, accompanied at most by a verbal description of the item and its methods of use. The authors hope to continue research in this area in the future after the problems caused by the epidemic have been resolved.

3.2. Level 1. Limited Assimilation of Technology and Symbolic Meaning

At level 1, we can use many scattered examples related to the limited use or reduction of traditional technologies that have lost their previous economic importance or have only a limited use today. This level of preservation of traditional technology relies on its reduction only to the symbolic sphere. An important context here is the maintenance of the use of traditional products in the ritual sphere allowing them to maintain the unchanged form of rituals associated with a given activity. In modern reality, it is possible to find many examples of a similar reduction of traditional technologies (not only tools) to the symbolic sphere. In Polish cultural realities, it is visible, among others, in the rituals associated with Easter. Foods that are brought by the Poles to churches for consecration are still placed in wicker baskets, which in traditional rural culture was the usual way of storing and transporting food products. Currently, they are used primarily in the context of Easter. Products for transporting food made of wicker and wood have been replaced in everyday use products made of plastics and other “modern” materials.

Nowadays, a certain return to the old materials can be noticed, but it already has completely new meanings related to pro-ecological thinking or conscious references to the rustic, traditional, and naturalness of products. It can be hypothesized that most wicker products are associated with the rustic style or other styles in interior decoration, which are to be associated with naturalness, slow life, the uniqueness of moments spent with the family, or a conscious choice of products that are not made of plastic. Interestingly, in this regard, many cheap interior design products made of plastic imitate wicker or rattan. This indirectly indicates the connotations associated with the use of such traditional materials, though not necessarily traditional items. In the case of wickerwork, there seems to be great potential not only for preservation, but also for sustainable development because natural wicker products are treated as high-quality products and in some contexts even become luxury products, so-called Veblenian goods.

The sphere of religion is also a place for the preservation of traditional folk art and artistic craftsmanship. In Poland, the devotional market is very well developed, although, unfortunately, a large part of it consists of low-quality reproductions and plastic products. In this regard, the Church could play a major role in promoting higher-quality products made with traditional methods and with natural materials.

The sphere of rituals in contemporary society is, of course, not limited to religious rituals, but is extended to other spheres of activity, not only on festive occasions but also during leisure, social meetings, hobbies, and sports activities, i.e., in spheres strongly related to the use of Veblenian goods, in which the standard economic account is not the most important motivation for consumer choices.

Objects in the field of crafts, including artistic craftsmanship, are treated as interesting decoration, even while maintaining the functions typical for a given object. According to the data of the Polish Central Statistical Office (GUS), in 2020, among products from the area of works of art and antiques purchased by Poles, those made of artistic craftsmanship accounted for only 4.9% [

23].

We could, however, observe that the perspective of buyers changes and affects the use of traditional technology. This is shown, interestingly, in the 2017 Eurobarometer survey in which respondents were asked about their involvement in cultural heritage. Only 8% of EU citizens declared that they have mastered the skills or knowledge related to one or several traditional crafts (e.g., weaving, decorative art, embroidery, making musical instruments or pottery, etc.) [

24]. On the other hand, it seems that “handmade” information increases the value of the item rather than lowers it.

An interesting category of products are those promoted or stylized as traditional Polish crafts, the best example of which are the products sold under the “Cepelia” brand. When analysing the items offered for sale there, often apart from the use of materials such as wood or references to folk culture, through the attire of a doll and traditional design references, they have little to do with traditional handicrafts, especially in terms of their production. The consumer is in their case often thought to be from outside the group in which a given product is created not only on the regional but also national scale. Those kinds of products are considered tourist souvenirs sold in tourist traps. Implications of the growing demand for handicrafts can be seen in different parts of the world. This is reflected in the situation of the craftsmen themselves and the direction in which the crafts are going, as exemplified by the situation of Chinese craftsmen [

25].

3.3. Level 2. Structural Conditions for the Duration, Change and Diversification of Technology

At level 2, a significant problem is the lack of quantitative data or even problems with quantitative methods of measuring the scale of the occurrence of traditional technologies. While in the case of market consumption we can use the data of the Polish Central Statistical Office (GUS), in the case of natural consumption, i.e., household production, or as part of the informal economy, such data must be obtained using other methods, including, above all, qualitative methods. We have indicated above that one of the most important statements at level 2 is that the new technology does not fully replace the earlier technologies, but only creates new divisions or fields of application characteristic of a given technology.

We can recall the category of “bricolage” described first by Lévi-Strauss and readapted by Tim Dant [

6] and compare it to the popularity of DIY activities (Do-It-Yourself). In French, “bricolage” is DIY, but it should be remembered that Lévi-Strauss uses this word to describe a situation in traditional cultures when elements of culture that are available at hand are used and are made to “stick together” to construct something new. To some extent, this is the opposite of industrial production, where materials, resources, and forms are selected for their intended purpose and method of use.

Modern home improvement is significantly different in terms of the materials used. Such materials are “purchased” in industrial form. Most often these are new materials, sometimes already pre-shaped for a given project, for example in the form of templates or prefabricated elements. This is visible in the growing popularity of DIY stores, which is also indirectly related to the situation on the market of selling construction products and interior furnishings. As shown by the data in 2016–2018, the retail DIY market grew in Poland at a rate of 6–7% annually, and in 2018 it was already worth over PLN 34 billion [

26].

The popularity of DIY stores, along with the popularity of stores with furniture or other articles for one’s own assembly, can be treated as an indirect indicator of the maintenance of various skills necessary to perform, even partially, certain activities independently. Of course, this will not be an indicator of keeping traditional crafts in their entirety, but an indicator of the diffusion of a variety of life-wide learning skills.

Paradoxically, a high level of skills in a given field within the entire population will not have a positive effect on the dissemination and the possibility of the economic success of specialized craftsmen. Only the disappearance of skills in a given area or the change from natural to market consumption may be the reason for the emergence of new craft specialities. A good example in this regard is the emergence of companies dealing with tailoring services, or rather sewing corrections, in recent years. This is, of course, a positive trend from a sustainability point of view, as otherwise such clothes could end up in the garbage. The same problem with “disposable” products is visible in the case of footwear and the decreasing interest in the services of shoemakers. A similar analysis could be done with other traditional technologies. In each case, we would probably find different situations related to the structural conditions of a given technology, but we would notice similar regularities.

3.4. Level 3. Functional Contexts of Using Traditional Technologies

As we indicated above, the disappearance of a given skill in a simple form within the entire population (within households) may become an impulse for the diversifying development of craft specialities, often at a higher level of technological advancement or higher handicraft efficiency, in which the production is directed toward the market. This type of tendency may also have been the origin of traditional crafts in the past. Furthermore, in many historical contexts, we have dealt with the regulation or corporation of craft professions, for example in the form of guilds or other associations aimed at regulating production and caring for the quality of products. Specialization and the growing division of labour is a phenomenon that has been identified for a long time (even since the Neolithic revolution). This apparently obvious context is sometimes forgotten in considerations related to the preservation of traditional crafts. They, too, had to be innovative and specialize at some point. For example, coopers, a job which seemed to be completely obsolete, can find outlets for barrels that are used in the increasingly popular Russian type saunas, where cold water baths are assumed after using the sauna. Such saunas often appear in homes that use other traditional technologies related to wood processing. Building a wooden house for a second residence is one of the trends noticeable in the upper classes of society. It may not be visible quantitatively, but it is qualitatively significant and creates new trends in consumption related to prestige.

The cultivation of traditional crafts and skills indicated at level 3 is indirectly related to the systemic approach to regulating what a craft is and who can be called it. According to the legal regulations, there are 141 craft professions in Poland and not all are associated with the traditional understanding of this area of activity. Apart from an engraver, amber craftsman, or embroiderer, an electrician, a roofer, or a bricklayer are also considered to be craftsmen. The latter may include traditional skills or individual units cultivating traditional technologies, although in the case of an electrician it is rather unlikely, and it would be difficult to define (at least so far) what “traditional electrics” would be. In the case of the former, there are also more or less traditional production techniques. Often in this respect, censorship becomes the use of mechanical and electric tools to facilitate the work of a given craftsman, although it is obviously arbitrary, controversial, and depends on the specialization.

Traditional craftsmanship or its use for economic purposes is connected, for example, with the establishment of theme villages. These are programs focused on targeting the profile of a given locality in terms of a specific product, referring to, inter alia, history, environment, or a focus on the promotion of traditional crafts [

27].

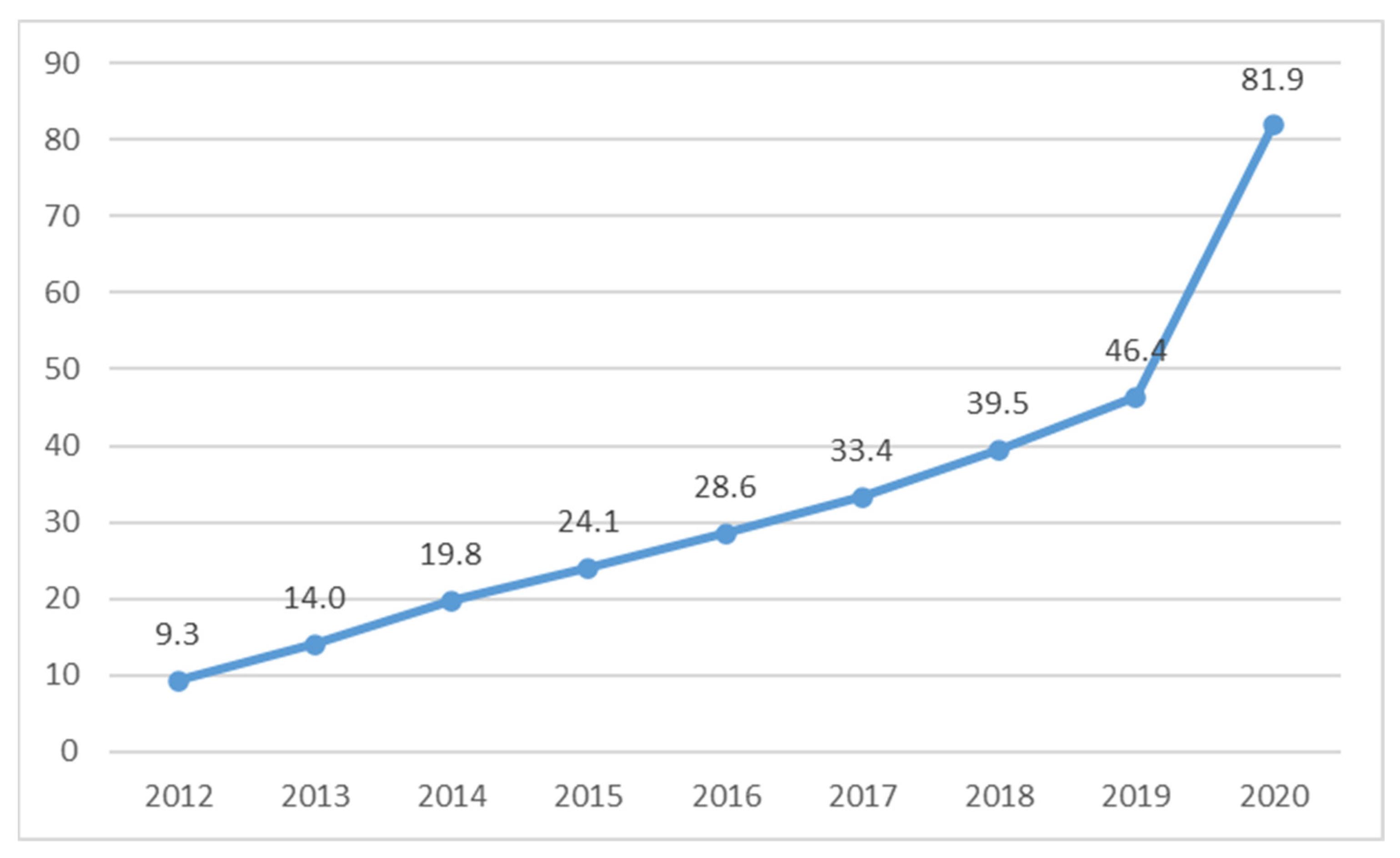

The trend of commercialization of handicrafts is also visible, and the global handicrafts market reached a value of US

$718 Billion in 2020 [

28]. Websites such as etsy.com and the Polish pakamera.pl are gaining popularity all the time. According to statistics, the number of active Etsy buyers from 2012 to 2020 grew dynamically from 9.32 million in 2012 to 81.9 million in 2020 [

29] (

Figure 1).

There is a growing recognition that funding or a shift towards crafts has the potential to reconfigure the economic system on its way to becoming more sustainable, including by valuing craft practices in terms of their impact on strengthening local identity but also the resilience of local and regional communities [

30]. Craft is also beginning to be considered as a “modern way of thinking” that teaches a kind of ecological wisdom, a certain holistic approach to the philosophy of responsible creating [

31].

3.5. Level 4. Non-Economic Motivations for the Preservation and Sustainable Development of Traditional Crafts

At level 4, we discuss the broadest contexts of the preservation and sustainable development of traditional crafts. We reflect on how a given technology influences the social structure—does it perpetuate it or change it? The hypothesis is that it is easier to accept technologies that fit into the existing social structure, into already existing social inequalities. The situation is different in the case of technologies which force social change or at least stimulate it. They will be received unfavourably by the current elite but may be positively received by the disadvantaged. Do activities aimed at the preservation of traditional crafts fall into the first or second category?

As we indicated above, nowadays we can see successive phases of changes that are causing rural areas to cease to be only suppliers of agricultural products and to become areas for spending free time, relaxing (which is related to the development of agritourism), and migration from urban areas of both people who (thanks to the development of telecommunications technologies) can perform their professional duties remotely and people who want to change their lifestyle and are starting to become interested in traditional technologies for autotelic, cultural and/or health or ecology reasons.

Rural areas are predominant in the EU and currently cover around 83% of its land area. They are inhabited by 30.6% of the EU’s population. These areas attract the most tourists in the EU [

32]—“at the EU level, the number of tourism nights per inhabitant in rural regions is three times higher than in urban regions” [

33]. This is related to the change in tourist preferences and the suppression of mass tourism. This indicates that tourists are now looking for other experiences related to a “return to nature and a renewed awareness of the environment, the rediscovery of local identity, and the search for both physical and psychological well-being (…)” [

34]. Places that emphasize contact with nature or promote food in the slow style or related to local traditions, such as the traditional production of cheese, cold meats, or regional alcoholic beverages, known as craftsmanship, are interesting destinations. Closely related to these tourist destinations are the terms “agro-”, “agri-”, and “rural”, which are related to local culture-based services. This trend refers to cultural heritage, cultural tourism, and community-based tourism [

35].

In recent decades, we can observe the formation of a new social structure in rural areas, especially those that are within the reach of larger urban agglomerations. In addition to the “former” inhabitants who make a living from agriculture, we see the emergence of a new category of inhabitants who earn their living from working in urban areas. This process is not directly related to traditional crafts. Although newcomers often also deal with agritourism, they become customers of local craftsmen and they create a new atmosphere in the countryside. They are often more aesthetic oriented, seek and support local traditions, get involved in local associations, and are more oriented towards the possibilities of obtaining external support for local cultural heritage activities. They are often interested in traditional, wooden houses that were not attractive to rural residents oriented primarily towards improving the quality of life that was associated with urban areas and modern “city-like” buildings. This is a change that can potentially promote the renaissance of traditional crafts. Of course, it is only one of the trends, and it does not describe all rural areas’ new inhabitants but only those who are more oriented towards post-materialistic values. We will come back to this question below.

Nowadays, perhaps, traditional technologies and the old ways of life (slow life) are a weapon in the revolution related to ecological trends. We can distinguish the search for solutions in traditional technologies that are environmentally friendly and sustainable. This new motivation or “new” value changes the calculation of factors from previous levels. We add an additional factor influencing the overall assessment, which does not always have to be in favour of traditional technologies and may encourage a selective approach to tradition.

The interest in traditional technologies in connection with a healthy lifestyle and ecology is especially visible in the context of purchasing products that have a direct impact on us. Interesting results are provided by the Accenture report, in which more than 25,000 consumers across 22 countries took part with follow-up focus groups in five countries. The report indicates that the period of the pandemic changed the approach of customers to purchasing. The authors of the report indicate that a new category of consumers, the “Reimagined”, is emerging. Furthermore, research shows that they are a group that no longer follows the typical division of product quality and price but also highlights other features that distinguish the product, including health and safety, product origin, trust and reputation, service and personal care, and ease and convenience [

36].

The change in consumer attitudes is most evident in the product category of food. Sustainability is of increasing importance for Europeans when shopping for food, especially in Portugal, Italy, and Spain. An increasing number of consumers in the European Union are starting to pay attention not only to affordability when shopping for food but also to sustainability. This approach is declared by almost half of Poles (45%), followed by Italians (39%) and Spaniards (35%) [

37].

As we indicated above, the situation is different in the case of fully autotelic motivations to preserve cultural traditions or motivations related to cultural or national identity. Here, the most important thing is the complete preservation of a given habit—its internal coherence—and not external compliance with the social structure or original functions or emphasizing the “familiarity” of a given habit, skill, or object, regardless of the economic, ergonomic, or ecological calculations.

One example of this is the program EtnoPolska founded by the National Center for Culture in Poland [

38]. In the description of the project, we read: “The program serves the development of activities in the field of regional education and dissemination of knowledge about traditional values present in the material and non-material culture of communities away from large centres of cultural life. The undertaken initiatives may refer directly to cultural traditions, be inspired by them, as well as present them in contemporary contexts. The program includes tasks in the field of folk and amateur creativity in many areas, taking into account traditional handicrafts and crafts, as well as unique phenomena of rural and urban folklore, which significantly affect the growth of cultural capital, activation and raising the level of social integration in areas with difficult access to cultural goods” [

38]. This program is interesting for two reasons. First, it takes almost completely traditional crafts from the economic sphere and transfers them to the sphere of national identity and culture. Secondly, it emphasizes locality and diversity, which is the basis for building a national identity. However, it cannot be ignored that it folklorizes traditional craftsmanship, placing it next to folk costumes or folk songs and dances performed on stage by local bands. Such a juxtaposition shows that traditional craftsmanship is understood to have only “folkloric”, historical, and not practical significance. From this perspective, this program can be considered a continuation of the thinking that each region should have its folk costume, which will be specific to it, but at the same time will be standard within the region. The collection of standard costumes will create a “canon of national culture” at the national level. The processes of the folklorization of folk art, crafts, and traditional garments in Poland were brilliantly described by Józef Burszta [

39]. He emphasizes the differences between folk art and traditional products created as part of peasant culture and products of “folklore”, which are consciously subordinated to formal patterns of folk art, in which the creator tries to maintain or master the folk style and to cultivate in this style the folk themes. The above-described “Cepelia” dealt with the sale of such products.

We find another situation in the above-noticed tension between fashion (changeability, the search for constant novelties) proper to modernity, and the “patina”, that is, emphasizing the continuity and old roots, which were characteristic of the old nobility, for people who wanted to emphasize their unique roots. We concluded that even if today it is no longer necessary to emphasize “nobility” in the strict sense, a reference to “patina” seems a probable solution when we begin to “create an identity”. Thus, it will not be a lazy routine or an inability to adapt to the changing world, but the choice of a “cultural pattern” that will emphasize our uniqueness and will emphasize the continuity of certain customs.

This approach is well represented in a recent book by Katarzyna Młynarczyk and Bartłomiej Rak Rzemieślnicy—

10 Inspirujących Historii o Pracy Ludzkich Rąk. (Craftsmen. 10 Inspiring Stories about the Work of Human Hands) [

40]. As the title suggests, this is not a scholarly study but a transcript of interviews with ten “modern” craftsmen. “Being a modern artisan is not just about work. It is a lifestyle that is determined by passion, sensitivity to materials, pro-ecological attitude and respect for the customer”, write the authors of

Rzemieślnicy. They propose a very interesting definition of a craftsman that goes beyond the official legal definitions in force in Poland. They propose six criteria that they used to choose whom to interview. These are individualism, authenticity, uniqueness, durability, reliability (associated with good quality), and awareness. According to them, individualism is associated with courage and the will to change, often born out of rebellion against the current perception of a given industry, product area, or idea. Authenticity is associated with the person, but also with the created product, which should be characterized by social and ecological responsibility and the use of the goods of the craftsman’s region, which is to be an expression of credibility and respect. Uniqueness is not directly related to innovation but to the uniqueness of the approach and the personality of a given person, which makes a given item different than those made by other manufacturers. They define durability in a very interesting way because they pay attention not only to the literal durability of materials and long-term operation of the product, but also to the metaphorical durability of the idea behind a given product. This is directly related to the integrity and good quality of the products, which they consider to be self-explanatory concepts. The last is the awareness of the needs of a modern client, but also the awareness of the craftsman’s own business strategy, which is included in the answers to the question of whom he creates for, what he expects, and whether he knows contemporary forms of communication and the possibilities of reaching out with his products and actions to the customer.

They are aware and make it clear that their definition is subjective, but they emphasize that it is inspired by the history of craftsmanship. As we can see, they are not concerned with the antiquarian accuracy of preserving a given craft but with giving it a new spirit that will correspond to modern times—but at the same time they retain the essence of being a craftsman. They place craftsmanship in direct opposition to the exuberant consumerism that seems to be mainstream in modern times. They emphasize that some of the craftsmen they talked to are people who continue their family traditions but that there are also people who have quit their job in corporations to find individual fulfilment. We can see here a change from the assigned status of a craftsman related to the intergenerational inheritance of a profession to an attained status related to a conscious life choice not necessarily (as is often assumed) at an early stage in life and less related to the economic necessity associated with low prestige and negative choices within the educational system (crafts as a way for less talented students who cannot continue their education), and more and more related to positive choices of non-mainstream life paths of people who have experienced the negative sides of life in big cities and working in capitalist corporations and businesses.

4. Conclusions

In our study, we argue that we can speak of preservation of cultural heritage when not only the given object or work is preserved, but also when the methods of production and/or use are preserved, at least in the potential form of a possible return to them in the future. The preservation of objects without traditional use or production methods can be seen, for instance, in the contexts of upcycling, museum exhibits, and decorations. We claim that these are insufficient for the preservation of traditional crafts because they do not keep traditional crafts alive as such—but only the memory of them.

The essence of upcycling is not the preservation of the original item but its transformation. Not even the object itself is important here, but the materials from which it is made. Former items are treated here as rubbish or unwanted parts that would otherwise end up in a landfill or would be processed only at the level of the materials from which they were made. It becomes a new way of running a business based on the principles of sustainable development but not aimed at preserving cultural heritage. At this level, we are not dealing with the preservation of traditional technologies either in terms of tangible heritage or intangible cultural heritage, even though this action should certainly be assessed positively when we take into account sustainable growth and ecological responsibility.

The question of the manufacturer and the methods of production understood as an intangible cultural heritage is of significant importance when we consider traditional crafts. The most common place where we can meet traditional crafts in developed societies is at museum exhibitions. Many museums try to go beyond the mere preservation of traditional craftsmanship by organizing shows for visitors during which the visitor can see the work of a craftsman. Such displays are an opportunity to see not only objects but also the ways in which objects are made and used, which is one of the keys to preserving traditional crafts understood as intangible heritage.

Figure 2 shows the key elements of our model in a graphical form. The analysis at level 1 shows the minimum level of preservation of traditional technology, in which it is reduced only to the symbolic sphere (for ritual use). It can be assumed that items directly related to the symbolic layer of culture are not subject to the structural conditions that are visible in areas related to production and the economy. This sphere in contemporary societies is, of course, not limited to religious rituals but is extended to other spheres of activity, not only on festive occasions but also during leisure, social meetings, hobbies, and sports activities, i.e., in spheres strongly related to the use of Veblenian goods, in which the standard economic account is not the most important motivation for consumer choices.

Level 2 examines structural conditions for the duration, change, and diversification of technological, economic, and social factors influencing the use of traditional or new technologies.

Economic factors include the one-time cost of purchasing “new technology” but also issues related to the further maintenance of a given technology, such as the issue of access to a specialist who could repair the equipment or the purchase of fuel or spare parts. The complicated tools, due to their price, may turn out to be unprofitable in the case of small-scale production or occasional use. Here, traditional technologies have the advantage.

Social factors include the activities being performed at home and the case of making original products in small batches, while the time saved thanks to the use of modern technologies is shrinking. The use of traditional technologies dictated not only by economic necessity but perhaps also by a conscious choice related not only to pro-ecological attitudes but also to identity choices.

Level 3 discusses the functional contexts of using traditional technologies. We examined the problem of the context of using a given technology and we concluded that the key to solving the problem seems to be the creation of conditions for the cultivation of traditional crafts and skills not only and not so much as professional work, but rather as an “additional” activity—supporting other forms of earning and transferring traditional skills from the sphere of purely professional work to the sphere of free time, hobbies, or self-realization for people making conscious life choices, and not necessarily at a young age.

Level 4 raises the issue of non-economic motivations for the preservation and sustainable development of traditional crafts. In the case of fully autotelic motivations to preserve cultural traditions or motivations related to cultural or national identity, the most important thing is (1) the complete preservation of a given habit and its internal coherence—not external compliance with the social structure or original functions, or (2) the emphasis of the “familiarity” of a given habit, skill, or object, regardless of the economic, ergonomic, or ecological calculations.

We emphasize that the formulation of recommendations and policies for the preservation of cultural heritage should be based on the analysis of a given case on these four levels. We must take into account not only the method of production itself, but also its symbolic dimension, its location in a wider cultural framework, changes in the perception of a given craft in a changing society, and changes in the perception of crafts related to the challenges faced by the entire modern world, such as the need to protect the environment, fight climate change, and the non-economic motivations of modern man.

In light of Igor Kopytoff’s anthropological analysis of the commodification process, we can even consider whether the essence of cultural heritage is not its de-commoditization or its singularization. He points out that works of art (such as paintings by Rembrandt or Picasso) or historical objects have market value but are also superior to the world of commerce. In his opinion, the singularity is in opposition to commodity [

35]. Following this line of thinking, one could say that the more we try to commodify traditional craftsmanship, the less unique it becomes. The more it belongs to cultural heritage, the more it becomes priceless—but not worthless.