The Influence of CSR Practices on Lebanese Banking Performance: The Mediating Effects of Customers’ Expectations

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data Overview

3.2. Descriptions of Variables

3.3. Methodology

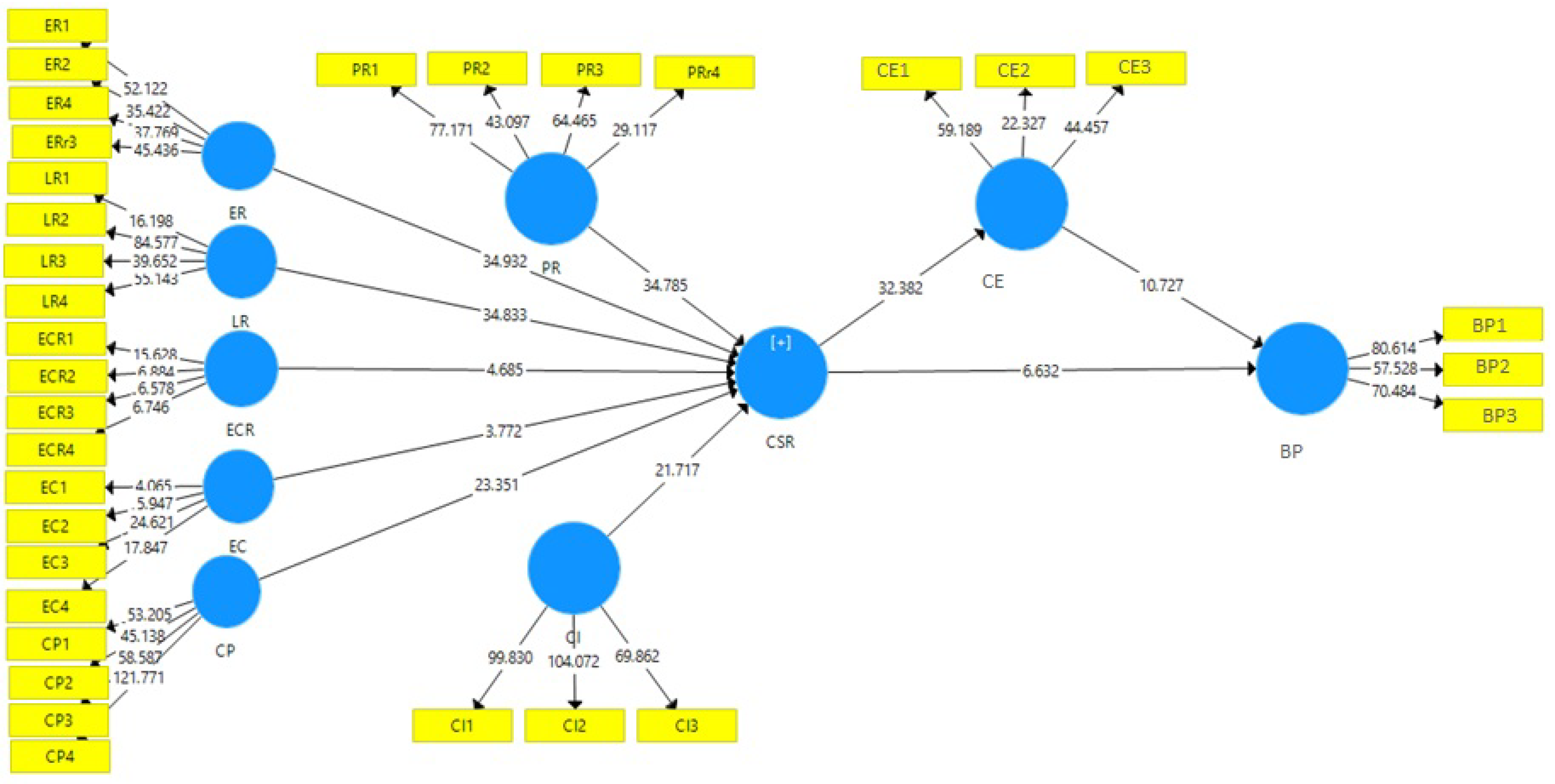

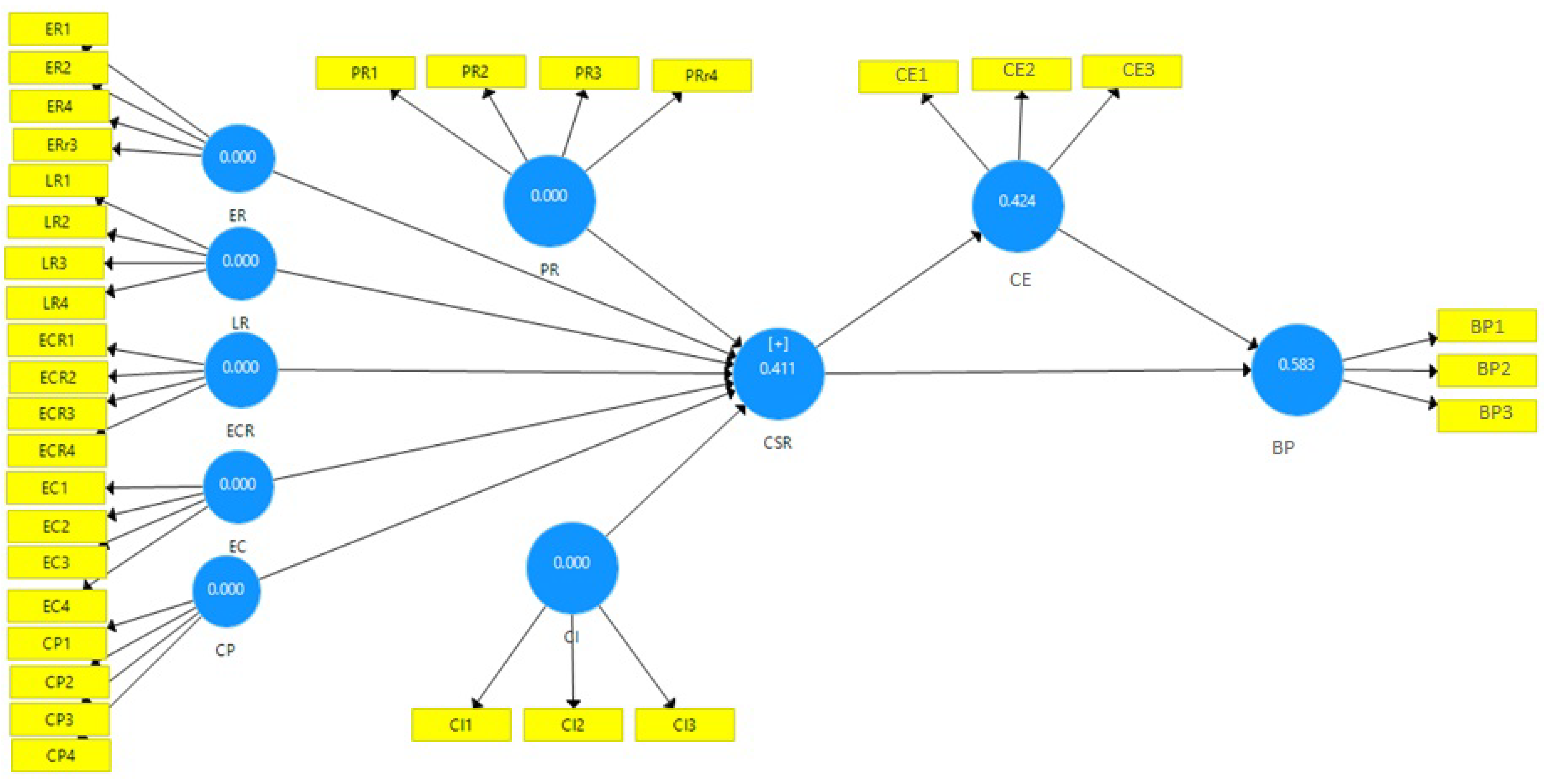

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM)

4. Estimation Results

4.1. Demographic Coverage

4.2. PLS-SEM Results

4.3. Measurement Model Assessment

4.4. Convergent Validity

4.5. Discriminant Validity

4.6. Structural Model Assessment

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Items | VIF |

|---|---|

| CI1 | 1.833 |

| CI1 | 2.520 |

| CI2 | 2.414 |

| CI2 | 1.716 |

| CI3 | 2.480 |

| CI3 | 2.448 |

| BP1 | 2.212 |

| BP2 | 1.941 |

| BP3 | 2.364 |

| CP1 | 2.538 |

| CP1 | 1.801 |

| CP2 | 2.442 |

| CP2 | 2.291 |

| CP3 | 2.610 |

| CP3 | 2.801 |

| CP4 | 2.464 |

| CP4 | 1.948 |

| CE1 | 1.858 |

| CE2 | 1.452 |

| CE3 | 1.910 |

| EC1 | 1.814 |

| EC2 | 2.140 |

| EC3 | 2.037 |

| EC3 | 2.167 |

| EC4 | 2.028 |

| EC4 | 2.165 |

| ECR1 | 1.119 |

| ECR1 | 1.607 |

| ECR2 | 2.654 |

| ECR2 | 2.543 |

| ECR3 | 2.848 |

| ECR3 | 2.154 |

| ECR4 | 1.479 |

| ER1 | 1.964 |

| ER1 | 2.064 |

| ER2 | 2.140 |

| ER2 | 1.533 |

| ER4 | 2.313 |

| ER4 | 2.571 |

| ER3 | 2.106 |

| ER3 | 2.611 |

| LR1 | 1.383 |

| LR1 | 2.575 |

| LR2 | 2.699 |

| LR2 | 1.838 |

| LR3 | 2.110 |

| LR3 | 2.481 |

| LR4 | 2.898 |

| LR4 | 2.256 |

| PR1 | 2.976 |

| PR1 | 2.914 |

| PR2 | 2.241 |

| PR2 | 2.854 |

| PR3 | 2.460 |

| PR3 | 1.544 |

| PR4 | 2.049 |

| PR4 | 2.791 |

| CI | BP | CP | CE | CSR | EC | ECR | ER | LR | PR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI1 | 0.925 | 0.741 | 0.814 | 0.697 | 0.775 | 0.184 | 0.385 | 0.512 | 0.547 | 0.564 |

| CI1 | 0.925 | 0.741 | 0.814 | 0.697 | 0.775 | 0.184 | 0.385 | 0.512 | 0.547 | 0.564 |

| CI2 | 0.923 | 0.792 | 0.792 | 0.791 | 0.764 | 0.220 | 0.361 | 0.533 | 0.524 | 0.545 |

| CI2 | 0.923 | 0.792 | 0.792 | 0.791 | 0.764 | 0.220 | 0.361 | 0.533 | 0.524 | 0.545 |

| CI3 | 0.895 | 0.740 | 0.797 | 0.706 | 0.736 | 0.182 | 0.297 | 0.502 | 0.496 | 0.522 |

| CI3 | 0.895 | 0.740 | 0.797 | 0.706 | 0.736 | 0.182 | 0.297 | 0.502 | 0.496 | 0.522 |

| BP1 | 0.785 | 0.891 | 0.812 | 0.779 | 0.758 | 0.191 | 0.349 | 0.562 | 0.554 | 0.569 |

| BP2 | 0.669 | 0.860 | 0.646 | 0.735 | 0.651 | 0.135 | 0.267 | 0.533 | 0.512 | 0.480 |

| BP3 | 0.732 | 0.892 | 0.726 | 0.714 | 0.681 | 0.217 | 0.233 | 0.493 | 0.500 | 0.508 |

| CP1 | 0.692 | 0.710 | 0.875 | 0.656 | 0.767 | 0.252 | 0.293 | 0.585 | 0.575 | 0.579 |

| CP1 | 0.692 | 0.710 | 0.875 | 0.656 | 0.767 | 0.252 | 0.293 | 0.585 | 0.575 | 0.579 |

| CP2 | 0.723 | 0.694 | 0.867 | 0.636 | 0.743 | 0.243 | 0.344 | 0.510 | 0.548 | 0.538 |

| CP2 | 0.723 | 0.694 | 0.867 | 0.636 | 0.743 | 0.243 | 0.344 | 0.510 | 0.548 | 0.538 |

| CP3 | 0.833 | 0.735 | 0.870 | 0.690 | 0.738 | 0.207 | 0.335 | 0.484 | 0.492 | 0.505 |

| CP3 | 0.833 | 0.735 | 0.870 | 0.690 | 0.738 | 0.207 | 0.335 | 0.484 | 0.492 | 0.505 |

| CP4 | 0.840 | 0.785 | 0.917 | 0.793 | 0.834 | 0.207 | 0.417 | 0.600 | 0.598 | 0.640 |

| CP4 | 0.840 | 0.785 | 0.917 | 0.793 | 0.834 | 0.207 | 0.417 | 0.600 | 0.598 | 0.640 |

| CE1 | 0.710 | 0.726 | 0.726 | 0.867 | 0.707 | 0.205 | 0.283 | 0.557 | 0.536 | 0.540 |

| CE2 | 0.574 | 0.642 | 0.538 | 0.768 | 0.508 | 0.120 | 0.164 | 0.436 | 0.324 | 0.349 |

| CE3 | 0.717 | 0.753 | 0.704 | 0.879 | 0.722 | 0.235 | 0.278 | 0.553 | 0.601 | 0.566 |

| EC1 | 0.079 | 0.046 | 0.082 | 0.058 | 0.109 | 0.535 | 0.106 | 0.063 | 0.083 | 0.098 |

| EC2 | 0.059 | 0.046 | 0.092 | 0.092 | 0.092 | 0.679 | 0.056 | 0.013 | 0.096 | 0.042 |

| EC3 | 0.232 | 0.244 | 0.288 | 0.239 | 0.297 | 0.906 | 0.058 | 0.209 | 0.220 | 0.182 |

| EC3 | 0.232 | 0.244 | 0.288 | 0.239 | 0.297 | 0.906 | 0.058 | 0.209 | 0.220 | 0.182 |

| EC4 | 0.184 | 0.167 | 0.207 | 0.207 | 0.225 | 0.853 | 0.004 | 0.127 | 0.203 | 0.114 |

| EC4 | 0.184 | 0.167 | 0.207 | 0.207 | 0.225 | 0.853 | 0.004 | 0.127 | 0.203 | 0.114 |

| ECR1 | 0.436 | 0.408 | 0.481 | 0.330 | 0.529 | 0.099 | 0.845 | 0.351 | 0.436 | 0.414 |

| ECR1 | 0.436 | 0.408 | 0.481 | 0.330 | 0.529 | 0.099 | 0.845 | 0.351 | 0.436 | 0.414 |

| ECR2 | 0.119 | 0.051 | 0.090 | 0.099 | 0.185 | -0.032 | 0.690 | 0.155 | 0.115 | 0.174 |

| ECR2 | 0.119 | 0.051 | 0.090 | 0.099 | 0.185 | -0.032 | 0.690 | 0.155 | 0.115 | 0.174 |

| ECR3 | 0.138 | 0.107 | 0.129 | 0.148 | 0.181 | -0.001 | 0.680 | 0.118 | 0.105 | 0.138 |

| ECR3 | 0.138 | 0.107 | 0.129 | 0.148 | 0.181 | -0.001 | 0.680 | 0.118 | 0.105 | 0.138 |

| ECR4 | 0.153 | 0.070 | 0.114 | 0.076 | 0.148 | 0.006 | 0.616 | 0.042 | 0.127 | 0.104 |

| ER1 | 0.522 | 0.554 | 0.564 | 0.526 | 0.765 | 0.109 | 0.280 | 0.838 | 0.655 | 0.773 |

| ER1 | 0.522 | 0.554 | 0.564 | 0.526 | 0.765 | 0.109 | 0.280 | 0.838 | 0.655 | 0.773 |

| ER2 | 0.437 | 0.478 | 0.491 | 0.483 | 0.717 | 0.139 | 0.270 | 0.846 | 0.717 | 0.655 |

| ER2 | 0.437 | 0.478 | 0.491 | 0.483 | 0.717 | 0.139 | 0.270 | 0.846 | 0.717 | 0.655 |

| ER4 | 0.454 | 0.505 | 0.533 | 0.564 | 0.760 | 0.195 | 0.259 | 0.867 | 0.742 | 0.728 |

| ER4 | 0.454 | 0.505 | 0.533 | 0.564 | 0.760 | 0.195 | 0.259 | 0.867 | 0.742 | 0.728 |

| ER3 | 0.500 | 0.507 | 0.513 | 0.524 | 0.728 | 0.133 | 0.232 | 0.847 | 0.667 | 0.677 |

| ER3 | 0.500 | 0.507 | 0.513 | 0.524 | 0.728 | 0.133 | 0.232 | 0.847 | 0.667 | 0.677 |

| LR1 | 0.394 | 0.416 | 0.402 | 0.404 | 0.615 | 0.179 | 0.208 | 0.644 | 0.690 | 0.572 |

| LR1 | 0.394 | 0.416 | 0.402 | 0.404 | 0.615 | 0.179 | 0.208 | 0.644 | 0.690 | 0.572 |

| LR2 | 0.514 | 0.565 | 0.590 | 0.557 | 0.791 | 0.197 | 0.336 | 0.743 | 0.915 | 0.691 |

| LR2 | 0.514 | 0.565 | 0.590 | 0.557 | 0.791 | 0.197 | 0.336 | 0.743 | 0.915 | 0.691 |

| LR3 | 0.490 | 0.446 | 0.497 | 0.477 | 0.710 | 0.159 | 0.289 | 0.661 | 0.841 | 0.631 |

| LR3 | 0.490 | 0.446 | 0.497 | 0.477 | 0.710 | 0.159 | 0.289 | 0.661 | 0.841 | 0.631 |

| LR4 | 0.496 | 0.535 | 0.583 | 0.521 | 0.767 | 0.203 | 0.373 | 0.677 | 0.867 | 0.706 |

| LR4 | 0.496 | 0.535 | 0.583 | 0.521 | 0.767 | 0.203 | 0.373 | 0.677 | 0.867 | 0.706 |

| PR1 | 0.556 | 0.528 | 0.625 | 0.541 | 0.803 | 0.155 | 0.338 | 0.726 | 0.687 | 0.902 |

| PR1 | 0.556 | 0.528 | 0.625 | 0.541 | 0.803 | 0.155 | 0.338 | 0.726 | 0.687 | 0.902 |

| PR2 | 0.466 | 0.517 | 0.546 | 0.518 | 0.745 | 0.111 | 0.289 | 0.732 | 0.663 | 0.848 |

| PR2 | 0.466 | 0.517 | 0.546 | 0.518 | 0.745 | 0.111 | 0.289 | 0.732 | 0.663 | 0.848 |

| PR3 | 0.565 | 0.537 | 0.583 | 0.509 | 0.783 | 0.165 | 0.361 | 0.708 | 0.681 | 0.873 |

| PR3 | 0.565 | 0.537 | 0.583 | 0.509 | 0.783 | 0.165 | 0.361 | 0.708 | 0.681 | 0.873 |

| PR4 | 0.465 | 0.459 | 0.462 | 0.461 | 0.723 | 0.126 | 0.287 | 0.727 | 0.679 | 0.834 |

| PR4 | 0.465 | 0.459 | 0.462 | 0.461 | 0.723 | 0.126 | 0.287 | 0.727 | 0.679 | 0.834 |

Appendix B

| Age _______ Gender Male □ / Female □ | |||||||

| Variables | Items | Coded | Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

| Limit object of the study | 1. Are you living or working in Lebanon? | -- | |||||

| 2. Have you ever used banking services in Lebanon? | -- | ||||||

| Corporate image and understanding of CSR | 3. Have you ever heard of the concept ‘corporate social responsibility’? | -- | |||||

| 4. Corporate social responsibility is tax responsibility. | CSR01 | ||||||

| 5. Corporate social responsibilities include environmental protection, customer-centric policies, philanthropy and other aspects that society expects from corporations. | CSR02 | ||||||

| 6. Corporate social responsibility is about the maximisation of profits and dividends. | CSR03 | ||||||

| Environmental Contribution | 7. Bank X reduces electricity and power consumption. | EC01 | |||||

| 8. Bank X uses environmentally friendly products. | EC02 | ||||||

| 9. Bank X uses recyclable materials. | EC03 | ||||||

| 10. Bank X has the proper pollution control measures. | EC04 | ||||||

| 11. Bank X keeps the internal environment neat and clean. | EC05 | ||||||

| 12. Bank X keeps the external environment neat and clean. | EC06 | ||||||

| Customer Expectations | 13. Bank X’s staff are efficient, reliable, competent and well dressed. | CE01 | |||||

| 14. Bank X’s staff have a polite attitude and behaviour. | CE02 | ||||||

| 15. Bank X is recruiting more staff for customer service. | CE03 | ||||||

| 16. Bank X focuses on opening new branches and increasing its services range. | CE04 | ||||||

| 17. Bank X gives customers high returns and charges lower fees on various transactions. | CE05 | ||||||

| 18. Banks should introduce new ways of convenient banking, such as mobile or internet banking. | CE06 | ||||||

| Philanthropic Responsibility | 19. Bank X is involved in organising different funds. | PR01 | |||||

| 20. Bank X raises funding for art exhibitions. | PR02 | ||||||

| 21. Bank X takes measures to deliver free financial planning knowledge to the public. | PR03 | ||||||

| 22. Bank X opens accounts for regularly donating money to orphanages. | PR04 | ||||||

| 23. Bank X provides poor children in remote areas with school supplies and nutritional lunches. | PR05 | ||||||

| 24. Bank X opens accounts in case of disaster for collecting and donating money in disasters. | PR06 | ||||||

| Bank Performance | 25. I choose bank X because it enacts environmental protection procedures. | BP01 | |||||

| 26. I choose bank X because it takes care of customers’ benefits. | BP02 | ||||||

| 27. I choose bank X because it is actively involved in philanthropic activities. | BP03 | ||||||

| 28. Corporate social responsibility influences my decision when considering a bank. | BP04 | ||||||

| 29. I do not choose banks based on whether they carry out their corporate social responsibilities. | BP05 | ||||||

| Ethical Responsibility | I think banking organisations should conduct risk assessment of financial products. | ER01 | |||||

| I think frontline staff of banking organisations should deeply understand complex financial services before offering them to customers. | ER02 | ||||||

| I feel banking organisations should protect the rights of customers when providing details of financial products. | ER03 | ||||||

| I think banking organisations should strengthen business ethics training for staff. | ER04 | ||||||

| Legal Responsibility | I think banking organisations should strengthen business ethics training for staff. | LR01 | |||||

| I think banking regulators should examine the suitability of advertisements of financial products to ensure the fulfilment of social responsibility. | LR02 | ||||||

| I think transparency regarding the monitoring of financial products by banking organisations to the public is lacking. | LR03 | ||||||

| I think banking organisations should show a bad attitude toward supporting greener industries. | LR04 | ||||||

| Economic Responsibility | I think banking organisations should provide lending options to low-income individuals and small businesses. | ER01 | |||||

| I think banking organisations should engage in community development. | ER02 | ||||||

| I think banking organisations should bring forth programs and policies to enrich the finance knowledge of banking service staff. | ER03 | ||||||

| I think banking organisations should be accountable for their performance. | ER04 | ||||||

| Consumer Protection | The Iinformation provided is clear and understandable. | CP01 | |||||

| The bank does not deduct money from hidden charges. | CP02 | ||||||

| The bank sends all necessary information to the customer. | CP03 | ||||||

| I think banking regulators should examine the suitability of advertisements of financial products to ensure the fulfilment of social responsibility. | CP04 | ||||||

References

- Vogler, D.; Gisler, A. The effect of CSR on the media reputation of the Swiss banking industry before and after the financial crisis 2008. UmweltWirtschaftsForum 2016, 24, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, L.M.; Rundle-Thiele, A.S. Corporate social responsibility and bank customer satisfaction: A research agenda. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2008, 26, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bravo, R.; Matute, J.; Pina, J.M. Corporate Social Responsibility as a Vehicle to Reveal the Corporate Identity: A Study Focused on the Websites of Spanish Financial Entities. J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 107, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocan, M.; Rus, S.; Draghici, A.; Ivascu, L.; Turi, A. Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility Practices on the Banking Industry in Romania. Proc. Econ. Finance 2015, 23, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kilic, M. The Effect of Board Diversity on the Performance of Banks: Evidence from Turkey. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcadell, F.J.; Aracil, E. European Banks’ Reputation for Corporate Social Responsibility. Corporate Soc. Respons. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W.; Frynas, J.G.; Mahmood, Z. Determinants of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Disclosure in Developed and Developing Countries: A Literature Review. Corporate Soc. Respons. Environ. Manag. 2017, 24, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benlemlih, M.; Girerd-Potin, I. Corporate social responsibility and firm financial risk reduction: On the moderating role of the legal environment. J. Bus. Finance Account. 2017, 44, 1137–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platonova, E.; Asutay, M.; Dixon, R.; Mohammad, S. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure on Financial Performance: Evidence from the GCC Islamic Banking Sector. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 451–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Orazalin, N. Corporate governance and corporate social responsibility (CSR) disclosure in an emerging economy: Evidence from commercial banks of Kazakhstan. Corporate Govern. 2019, 19, 490–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chedrawi, C.; Osta, A.; Osta, S. CSR in the Lebanese banking sector: A neo-institutional approach to stakeholders’ legitimacy. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2020, 14, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.; Kottasz, R. Public attitudes towards the UK banking industry following the global financial crisis. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2012, 30, 128–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayadi, M.A.; Kusy, M.I.; Pyo, M.; Trabelsi, S. Corporate Social Responsibility, Corporate Governance, and Managerial Risk-Taking. In Proceedings of the Canadian Academic Accounting Association (CAAA) Annual Conference 2015, Toronto, ON, Canada, 28–31 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chedrawi, C.; Osta, S. ICT and CSR in the Lebanese Banking Sector, towards a Regain of Stakeholders’ Trust: The Case of Bank Audi. 2018. Available online: http://www.unep.org/ (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Macaron, L.F. Impact of CSR activities on Organizational Identification (OI) and Job Satisfaction (JS) in Lebanese Commercial Banks. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Manag. Sci. 2019, 5, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiwo Adewale, M.; Adeniran Rahmon, T. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Improve an Organization’s Financial Performance?—Evidence from Nigerian Banking Sector. IUP J. Corporate Govern. 2014, XIII, 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Dujmović, M.; Vitasović, A. Tourism product and destination positioning. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 5, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- 19. Brunk, K H. Exploring origins of ethical company/brand perceptions—A consumer perspective of corporate ethics. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 255–262. [CrossRef]

- Alrumaihi, A.; Aaro, H. Corporate Social Responsibility in the Banking Industry in Kuwait Item Type Thesis. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10454/14866 (accessed on 4 October 2021).

- Dusuki, A.W. Corporate Social Responsibility of Islamic Banks in Malaysia: A Synthesis of Islamic and Stakeholders’ Perspectives. Ph.D. Thesis, Loughborough University, Loughborough, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; Chang, J. Corporate social responsibility and firm performance: The mediating role of marketing competence and the moderating role of market environment. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2015, 32, 505–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, A. The Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility on Customer Loyalty: A Study of the Banking Industry. Ph.D. Thesis, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Arja, A. The Role of Jordanian Multinationals in Countering Terrorism and Enhancing Security: A Stakeholder Approach. Ph.D. Thesis, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lourenço, I.C.; Branco, M.C.; Curto, J.D.; Eugénio, T. How does the market value corporate sustainability performance? J. Bus. Ethics 2012, 108, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, T.; Islam, R.; Pitafi, A.H.; Xiaobei, L.; Rehmani, M.; Irfan, M.; Mubarak, M.S. The impact of corporate social responsibility on customer loyalty: The mediating role of corporate reputation, customer satisfaction, and trust. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 25, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garriga, E. Corporate Social Responsibility Theories: Mapping the Territory. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 53, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maon, F.; Lindgreen, A.; Swaen, V. Organizational stages and cultural phases: A critical review and a consolidative model of corporate social responsibility development. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burianova, L.; Paulik, J. Corporate Social Responsibility in Commercial Banking—A Case Study from the Czech Republic. J. Compet. 2014, 6, 50–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cheema, S.; Afsar, B.; Javed, F. Employees’ corporate social responsibility perceptions and organizational citizenship behaviors for the environment: The mediating roles of organizational identification and environmental orientation fit. Corporate Soc. Respons. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menichini, T.; Rosati, F. A Fuzzy Approach to Improve CSR Reporting: An Application to the Global Reporting Initiative Indicators. Proc.-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 109, 355–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mosca, F.; Civera, C. The Evolution of CSR: An Integrated Approach, Symphonya. Emerg. Issues Manag. 2017, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, Y.; Liu, B.; Huan, T.C. Renewal or not? Consumer response to a renewed corporate social responsibility strategy: Evidence from the coffee shop industry. Tourism Manag. 2019, 72, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Saeed, A.; Iqbal, M.K.; Saeed, U.; Sadiq, I.; Faraz, N.A. Linking corporate social responsibility to customer loyalty through co-creation and customer company identification: Exploring sequential mediation mechanism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luu, T.T. CSR and Customer Value Co-creation Behavior: The Moderation Mechanisms of Servant Leadership and Relationship Marketing Orientation. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 155, 379–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, W.M.; Kim, H.; Kim, H.K. Does customer engagement in corporate social responsibility initiatives lead to customer citizenship behaviour? The mediating roles of customer-company identification and affective commitment. Corporate Soc. Respons. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1258–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, O.; Markovic, S.; Bagherzadeh, M.; Singh, J.J. Co-creation: A Key Link Between Corporate Social Responsibility, Customer Trust, and Customer Loyalty. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 163, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, S.; Sale, C. An analysis of corporate social responsibility, trust and reputation in the banking profession. In Professionals Perspectives of Corporate Social Responsibility; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, M.A.A.; Othman, M.; Mohamad, S.F.; Lim, S.A.H.; Yusof, A. Piloting for Interviews in Qualitative Research: Operationalization and Lessons Learnt. Int. J. Acad. Res. Business Soc. Sci. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kumar, N. Corporate Social Responsibility: An Analysis of Impact and Challenges in India. Int. J. Social Sci. Manag. Entrepreneur. 2019, 3, 53–63. [Google Scholar]

- Rigdon, E.E. The equal correlation baseline model for comparative fit assessment in structural equation modeling. Struct. Equat. Model. 1998, 5, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babin, B.J.; Joseph, F.H.; Boles, J. Publishing research in marketing journals using structural equation modeling. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2008, 16, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Bookstein, F.L. Two structural equation models: LISREL and PLS applied to consumer exit-voice theory. J. Mark. Res. 1982, 19, 440–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wold, H. Causal flows with latent variables: Partings of the ways in the light of NIPALS modelling. Eur. Econ. Rev. 1974, 5, 67–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albers, S. PLS and Success Factor Studies in Marketing. In Handbook of Partial Least Squares; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 409–425. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, K.-H.; Yu, J.-E.; Choi, M.-G.; Shin, J.-I. The Effects of CSR on Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty in China: The Moderating Role of Corporate Image. J. Econ. Bus. Manag. 2015, 3, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Straub, D.W. Editor’s comments: A critical look at the use of PLS-SEM in MIS Quarterly. MIS Quart. 2012, 36, iii–xiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anderson, J.C.; Kellogg, J.L.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, Y.; Brossier, R.; Operto, S.; Ribodetti, A.; Virieux, J. Which parameterization is suitable for acoustic vertical transverse isotropic full waveform inversion? Part 1: Sensitivity and trade-off analysis. Geophysics 2013, 78, R81–R105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Hubona, G.; Ray, P.A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: Updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, O.; Aldholay, A.; Abdullah, Z.; Ramayah, T. Online learning usage within Yemeni higher education: The role of compatibility and task-technology fit as mediating variables in the IS success model. Comp. Educ. 2019, 136, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, V.R.; Tan, K.C. Just in time, total quality management, and supply chain management: Understanding their linkages and impact on business performance. Omega 2005, 33, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Sarstedt, M.; Fuchs, C.; Wilczynski, P.; Kaiser, S. Guidelines for choosing between multi-item and single-item scales for construct measurement: A predictive validity perspective. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 434–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Correll, J.; Mellinger, C.; McClelland, G.H.; Judd, C.M. Avoid Cohen’s ‘Small’, ‘Medium’, and ‘Large’ for Power Analysis. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2020, 24, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgiic, A.; Huizinga, H. Determinants of Commercial Bank Interest Margins and Profitability: Some International Evidence. World Bank Econ. Rev. 1999, 13, 379–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, M.W.; Shen, C.H. Corporate social responsibility in the banking industry: Motives and financial performance. J. Bank. Finance 2013, 37, 3529–3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, C. Corporate Social Responsibility Practices in the Lebanese Banking Sector: A Reality or a Myth? Ph.D. Thesis, Notre Dame University-Louaize, Zouk Mosbeh, Lebanon, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristics | Total | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 620 | 62.0 |

| Female | 380 | 38.0 | |

| Qualification | Undergraduate | 522 | 52.2 |

| Graduate | 328 | 32.8 | |

| Post-graduate | 150 | 15.0 | |

| Association | 2–4 years | 176 | 17.6 |

| 5–7 years | 410 | 41.0 | |

| 8–10 years | 263 | 26.3 | |

| 10+ years | 151 | 15.1 | |

| Age (years) | 25–30 | 298 | 29.8 |

| 31–35 | 250 | 25.0 | |

| 36–40 | 145 | 14.5 | |

| 41–45 | 136 | 13.6 | |

| 46–50 | 98 | 9.8 | |

| 50+ | 73 | 7.3 |

| Constructs | Code | FD | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Philanthropic Responsibility | 0.887 | 0.922 | 0.748 | ||

| PR1 | 0.902 | ||||

| PR2 | 0.848 | ||||

| PR3 | 0.873 | ||||

| PR4 | 0.833 | ||||

| Ethical Responsibility | 0.872 | 0.912 | 0.722 | ||

| ER1 | 0.838 | ||||

| ER2 | 0.846 | ||||

| ER3 | 0.847 | ||||

| ER4 | 0.867 | ||||

| Legal Responsibility | 0.848 | 0.899 | 0.693 | ||

| LR1 | 0.690 | ||||

| LR2 | 0.915 | ||||

| LR3 | 0.841 | ||||

| LR4 | 0.867 | ||||

| Economic Responsibility | 0.756 | 0.803 | 0.508 | ||

| ECR1 | 0.844 | ||||

| ECR2 | 0.688 | ||||

| ECR3 | 0.680 | ||||

| ECR4 | 0.622 | ||||

| Environmental Contribution | 0.775 | 0.838 | 0.574 | ||

| EC1 | 0.554 | ||||

| EC2 | 0.695 | ||||

| EC3 | 0.898 | ||||

| EC4 | 0.846 | ||||

| Consumer Protection | 0.905 | 0.934 | 0.779 | ||

| CP1 | 0.874 | ||||

| CP2 | 0.867 | ||||

| CP3 | 0.871 | ||||

| CP4 | 0.917 | ||||

| Corporate Image | 0.902 | 0.939 | 0.837 | ||

| CI1 | 0.925 | ||||

| CI2 | 0.923 | ||||

| CI3 | 0.895 | ||||

| Customer Expectation | 0.790 | 0.877 | 0.704 | ||

| CS1 | 0.867 | ||||

| CS2 | 0.768 | ||||

| CS3 | 0.878 | ||||

| Bank Performance | 0.856 | 0.912 | 0.776 | ||

| BP1 | 0.892 | ||||

| BP2 | 0.859 | ||||

| BP3 | 0.892 |

| CI | CL | CP | CS | CSR | EC | ECR | ER | LR | PR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI | 0.915 | |||||||||

| BP | 0.829 | 0.881 | ||||||||

| CP | 0.876 | 0.829 | 0.883 | |||||||

| CE | 0.8 | 0.844 | 0.788 | 0.839 | ||||||

| CSR | 0.829 | 0.793 | 0.874 | 0.778 | 0.684 | |||||

| EC | 0.214 | 0.206 | 0.257 | 0.227 | 0.274 | 0.758 | ||||

| ECR | 0.381 | 0.323 | 0.395 | 0.293 | 0.467 | 0.06 | 0.713 | |||

| ER | 0.564 | 0.602 | 0.619 | 0.618 | 0.875 | 0.17 | 0.307 | 0.85 | ||

| LR | 0.571 | 0.593 | 0.628 | 0.592 | 0.87 | 0.222 | 0.367 | 0.819 | 0.832 | |

| PR | 0.595 | 0.591 | 0.643 | 0.587 | 0.884 | 0.162 | 0.37 | 0.835 | 0.783 | 0.865 |

| CI | CL | CP | CS | CSR | EC | ECR | ER | LR | PR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CI | ||||||||||

| BP | 0.419 | |||||||||

| CP | 0.424 | 0.517 | ||||||||

| CE | 0.517 | 0.575 | 0.275 | |||||||

| CSR | 0.498 | 0.32 | 0.498 | 0.651 | ||||||

| EC | 0.214 | 0.2 | 0.259 | 0.24 | 0.343 | |||||

| ECR | 0.337 | 0.27 | 0.321 | 0.275 | 0.498 | 0.124 | ||||

| ER | 0.635 | 0.695 | 0.694 | 0.739 | 0.27 | 0.169 | 0.27 | |||

| LR | 0.653 | 0.693 | 0.712 | 0.707 | 0.293 | 0.241 | 0.319 | 0.256 | ||

| PR | 0.663 | 0.675 | 0.713 | 0.69 | 0.224 | 0.169 | 0.333 | 0.739 | 0.694 |

| Hypothesis | Relationships | Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | T Statistics | p Values | Discussion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSR -> BP | 0.577 | 0.577 | 11.067 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| CSR -> CI | 0.829 | 0.829 | 37.244 | 0.002 | Supported | |

| CSR -> BP | 0.344 | 0.344 | 6.500 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| CSR -> CP | 0.874 | 0.874 | 52.548 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| CSR -> CE | 0.778 | 0.777 | 30.537 | 0.010 | Supported | |

| CSR -> EC | 0.274 | 0.279 | 4.536 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| CSR -> ECR | 0.467 | 0.471 | 9.462 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| CSR -> ER | 0.875 | 0.873 | 52.095 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| CSR -> LR | 0.870 | 0.868 | 44.621 | 0.003 | Supported | |

| CSR -> PR | 0.884 | 0.881 | 61.081 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| CP -> CSR -> CE -> BP | 0.119 | 0.118 | 9.526 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| EC -> CSR -> CE | 0.041 | 0.041 | 3.746 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| LR -> CSR -> CE -> BP | 0.087 | 0.087 | 10.268 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| CP -> CSR -> CE | 0.211 | 0.211 | 24.688 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| ER -> CSR -> BP | 0.075 | 0.076 | 6.633 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| PR -> CSR -> BP | 0.077 | 0.077 | 6.598 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| CSR -> CS -> BP | 0.442 | 0.441 | 10.592 | 0.002 | Supported | |

| ER -> CSR -> CE -> BP | 0.093 | 0.092 | 10.021 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| PR -> CSR -> CE -> BP | 0.095 | 0.094 | 10.174 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| LR -> CSR -> BP | 0.071 | 0.072 | 6.397 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| ECR -> CSR -> CE | 0.049 | 0.049 | 4.755 | 0.001 | Supported | |

| ER -> CSR -> CE | 0.165 | 0.165 | 23.872 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| PR -> CSR -> CE | 0.168 | 0.167 | 23.579 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| EC -> CSR -> CE -> BP | 0.023 | 0.023 | 3.536 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| CI -> CSR -> CE -> BP | 0.094 | 0.094 | 9.479 | 0.004 | Supported | |

| CI -> CSR -> BP | 0.076 | 0.077 | 6.568 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| ECR -> CSR -> BP | 0.022 | 0.023 | 3.826 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| LR -> CSR -> CE | 0.155 | 0.156 | 22.124 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| EC -> CSR -> BP | 0.019 | 0.019 | 3.305 | 0.001 | Supported | |

| ECR -> CSR -> CE -> BP | 0.027 | 0.028 | 4.340 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| CP -> CSR -> BP | 0.096 | 0.097 | 6.737 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| CI -> CSR -> CE | 0.167 | 0.167 | 22.625 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| CP -> CSR -> CE -> BP | 0.119 | 0.118 | 9.526 | 0.000 | Supported | |

| EC -> CSR -> CE | 0.041 | 0.041 | 3.746 | 0.000 | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hassanein, Z.; Yeşiltaş, M. The Influence of CSR Practices on Lebanese Banking Performance: The Mediating Effects of Customers’ Expectations. Sustainability 2022, 14, 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010268

Hassanein Z, Yeşiltaş M. The Influence of CSR Practices on Lebanese Banking Performance: The Mediating Effects of Customers’ Expectations. Sustainability. 2022; 14(1):268. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010268

Chicago/Turabian StyleHassanein, Zeina, and Mehmet Yeşiltaş. 2022. "The Influence of CSR Practices on Lebanese Banking Performance: The Mediating Effects of Customers’ Expectations" Sustainability 14, no. 1: 268. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010268