1. Introduction

In the past 40 years, with the global labor income share continuously declining, one of Kaldor’s views, namely that factor income share is basically constant [

1], has been heavily challenged by empirical evidence [

2,

3]. Since the mid-1990s, China’s labor income share has also been on a downward trajectory [

4,

5], exemplified by China’s labor income share dropping from 52% in 1993 to 39% in 2007 according to Luo and Zhang [

6]. Behind the decline of the labor income share lies another puzzling phenomenon: the rise in the savings rate. (We have found the same phenomenon in many developing countries. Take India as an example. From 1993 and 2007, India’s labor income share dropped from 64% to 47%. At the same time, the savings rate rose from 21% to 47%. The labor income share data comes from Penn Data Table 9.0, and the savings rate data comes from CEIC data.) As

Figure 1 shows, China’s savings rate showed an upward trend, with an average of 42.5% between 1993 and 2007. Note that China’s savings rate reached a staggering 51% in 2007 when measured by the expenditure method of GDP.

A closer look at

Figure 1 also shows that the decline in China’s labor income share and the rise in its savings rate began around the middle and late 1990s, which coincided with the beginning of China’s financial reform, a large-scale restructuring of China’s financial system conducted in the middle and late 1990s [

7]. Although the reform aimed at strengthening the principle of giving priority to the efficiency of credit issuance, the measures taken were tightening [

8]. One distinguishing feature of the reform is that financial institutions still give priority to state-owned enterprises as their funding targets, while the financing constraint environment of private enterprises has not improved correspondingly [

9]. This phenomenon makes us wonder whether financial constraints are the underlying cause of the decline in labor income share and the rise in the savings rate.

A series of studies have been conducted on the two typical phenomena of a rising savings rate and declining labor income share.

On the one hand, some scholars are committed to finding the causes against the background of the decline in global labor income share. Existing literature mainly focuses on the economic development stage and industrial structure adjustment [

10,

11,

12,

13], globalization [

3,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18] and capital-output ratio [

11,

19], the labor market system [

20,

21,

22], capital-biased technological change [

2,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27], while some scholars believe from the perspective of data that the adjustment of statistical caliber caused the illusion of the decline of labor income share [

28].

On the other hand, scholars mainly study the increase of the savings rate from the perspective of household savings, represented by precautionary saving motivation [

29,

30,

31], liquidity constraints [

32], consumption habits [

33], targeted consumption [

34,

35], fertility policy and structure, and so on [

36,

37,

38]. The literature above is important for interpreting the causes of high household savings in China. However, in terms of national savings, China’s national savings rate rose from 35% to more than 50% in between the 20 years from 1992 to 2012, while its household savings rate remained more or less the same around 20% but corporate savings doubled. It is thus not in line with China’s reality to only analyze the reasons behind the increase of household savings while ignoring the savings of enterprises. (National savings is divided into three parts. In most countries, household savings is the first part, followed by enterprise savings and government savings. However, China’s savings structure is obviously different from that of other countries.)

Unfortunately, the previous literature did not include the two typical phenomena of declining labor income share and rising savings rate into a unified analytical framework. There must be a certain connection mechanism behind the simultaneous existence of two abnormal phenomena in an economy. The motivation for us to study further the coexistence of declining labor income share and rising savings rate comes from the following two publications. First, Song et al. [

5] found that financing difficulties of private enterprises had been an important factor hindering the further development of China’s economy for a long time. Non-state-owned enterprises often have to rely on informal channels such as retained earnings, entrepreneurs’ personal savings and private lending to finance their operations and development. However, this fails to analyze how companies achieve their goals.

Second, Li and Yin [

39], based on the 1992–2003 Chinese capital flow table, found that the enterprise savings rate showed a slowly rising trend, which was not because of the improvement of enterprise profitability, but because of its main expenditure—the labor remuneration expenditure to the resident department was stabilized at a low level. However, it does not say which types of firms (state-owned or non-state-owned) contributed to the increase in the overall corporate savings rate, nor does it analyze what caused such firms to lower labor payments. This study provides a supplement and extension of the two articles above.

To sum up, the key question this paper aims to answer is: What micro-mechanism and factual logic lead to the simultaneous decline in the labor income share and the rise in the savings rate? This paper intends to build a bridge between the decline of labor income share and the rise of savings rate from the perspective of financial constraints, thus filling a gap in the research with respect to the theoretical integrity and policy feasibility of both related studies.

In order to construct the general theoretical model, this paper first reviews the Chinese economic stylized facts and finds out that since the mid-1990s, the increase in China’s savings rate has mainly come from enterprises, especially private enterprises, rather than, as is commonly believed, from the increase of the household savings rate. The decline in the labor income share also comes from private enterprises. Interestingly, with the increase in the savings rate and labor income share, it has become increasingly difficult for private enterprises to obtain financing. Based on basic economic facts, this paper argues that the imperfection of China’s financial market makes non-state-owned enterprises more inclined toward “crowding out” workers’ remuneration than saving for endogenous financing, which leads to rising savings rates and continuous decline of labor income share.

Summarizing the facts of the economic characteristics, we further expand the diamond model and the overlapping generation model to introduce financing constraint into the cost of obtaining credit for enterprises. Financing constraint makes it difficult for capital to flow to enterprises with high production efficiency. As a result, efficient enterprises tend to crowd out workers’ remuneration to conduct endogenous financing, thus reducing the labor income share.

Following the theoretical models, we adopt the intermediary effect model and use the Chinese Industrial Enterprises Database from 1999 to 2007 to conduct an empirical analysis. We find that the imperfect financial market significantly reduces the labor income share in China: the labor income share will decrease 0.051 percentage points when financial constraints increase by 1 percentage point. In the process of financing constraint affecting labor income share, the increase of savings of non-state-owned enterprises plays the role of an intermediary variable. The above empirical results are consistent with the theoretical analysis and explain the abnormal phenomenon that the rise of the savings rate in China is accompanied by the decline of the labor income share.

Finally, we forecast the trend of the labor income share after the end of China’s economic transformation. The calibration and quantitative prediction based on the theoretical model finds that by the end of China’s economic transformation, the distorted credit constraints will be eased, China’s savings rate will decline after reaching its peak, and the labor income share will bottom out and rise.

The results of this paper explain the imbalance of the rise in China’s savings rate and the fall in labor income share from the perspective of financing constraints, in the context of many developing countries, such as China, which are experiencing a decline in labor income share and an increase in savings rate. It also examines a new potential explanation for the reduction of labor income share in the context of the continuous decline of global labor income share [

2,

3]. Considering the large impact of declining labor income share on income inequality [

40] and the negative effect of income inequality on sustainable development [

41,

42,

43], the results of this paper provide empirical evidence and a policy path for other developing countries with imperfect financial markets to carry out financial system reform and increase labor income share so as to promote sustainable economic development.

The rest of this paper is arranged as follows:

Section 2 is a literature review;

Section 3 provides a mechanism analysis based on China’s economic characteristics;

Section 4 constructs the theoretical model;

Section 5 outlines the empirical design and data descriptions;

Section 6 showcases the empirical results with in-depth discussions, followed by the calibration and prediction in

Section 7, while

Section 8 provides the conclusion.

4. Theoretical Model

In this section, we model the characteristic facts of the third analysis and construct a more general economic model to provide guidance for subsequent empirical research. Suppose that the economy is described in accordance with the diamond model in a two-period framework, and consider the economy as having only two sectors, household and business. First, on the residents’ side, we consider the typical overlapping generation model: we have two phases, the first of which is at work and the second of which passes away and leaves us savings. The total output of both periods is normalized to 1. Any individual works in the first period (each person provides a fixed unit of labor) and divides his income into consumption and savings. The consumption of the individual in the second period is the return brought by the savings in the first period. All individuals enjoy the same utility function, assuming that their preference parameters are expressed in the form of the utility function:

In the above formula, t refers to time, is the discount factor, is the intertemporal elasticity of substitution of the consumption, and c stands for the consumption of the individual. Presume that , namely the individual’s savings, is the non-decreasing function of the rate of the return on savings. Taking a representative individual as an example, stands for the consumption level when the individual is young. stands for the consumption level when the individual is old.

The term resident mentioned in the thesis falls into two kinds. One refers to common workers (

), and the other to managers who have management skills (

) that can be inherited from their father’s generation. Population growth rate is exogenous

. Therefore, the following formula can be established:

in the above formula refers to the changes of the population structure trend, including migration from rural areas to urban areas.

There are three kinds of enterprises existing in the market, namely, Enterprise

S, Enterprise

F and Enterprise

H. The formulas for these enterprises are as follows:

Y in Formulas (4)–(6) refers to the output. K and n stand for capital and labor, respectively. Enterprise S is owned by the intermediary; its model is defined by the typical neo-classic model. Enterprise F is owned by the older entrepreneur. The older entrepreneur has a residual claim to corporation F’s profits and to hand down his position to his sons or daughters. Enterprise H is a self-sufficient enterprise. The model put forward in the thesis is based on two hypotheses. Firstly, the production among enterprises is different. The major difference between Formulas (4) and (5) is that Enterprise F must improve its level of productivity in order to survive in the market, while the F company must improve its production efficiency , . Its production method is to employ other labor; is an endogenous variable number instead of a fixed value. Formula (6) stands for their own production function, in which . An enterprise employing this production model works for itself without employing other people. Therefore, , namely . In the formula, .

In addition, there are financial constraints in the financial market. S enterprises with low production efficiency are not subject to financial constraints. They can easily obtain the funds they use in the financial market and mainly use exogenous financing methods (borrowing from banks or financing in the capital market). However, the F enterprise, with high production efficiency, has relative difficulty in financing. Affected by financial constraints, it finds it difficult to finance in the financial market, and tends to conduct endogenous financing by “crowding out” workers’ remuneration. Among them, the F enterprise can exist in this market mainly because of its high production efficiency. Therefore, compared with Enterprise S, Enterprise F, which is constrained by financing, will invest more in the improvement of production efficiency, and its level can be set as A. Of course, if such a production efficiency level is not invested, enterprises with low production efficiency can hardly survive in the market.

Ordinary individuals without entrepreneur qualifications can choose to work for

F company to get returns

. After receiving the return on their labor, the average individual can spend part of it on current consumption

, and save the rest as money

in the bank or in other financial institutions to obtain a capital return rate. Therefore, the intertemporal budget constraint of common laborers is expressed in Formula (2). Combine Formulas (1) and (2) to maximize the target function, and the following Lagrangian can be written:

From the necessary first-order conditions it can be conducted:

An entrepreneur, in the first phase, takes part in the production of his own enterprise and provides a unit labor or the enterprise’s ability to gain repayment , in which refers to the enterprise’s production profit (general output deducting tax revenue and payment to the employers) and stands for the profit proportion gained by the enterprise manager (). The remaining profit belongs to the older entrepreneur, who is a part of the paternal generation with respect to the young entrepreneur. The hypothesis ensures the principle that the manager and the enterprise have the same goal. At the end of the first phase, the young entrepreneur can deposit savings in the bank or invest in his own enterprise to form capital. In addition, the entrepreneur can obtain a loan from the bank. The sum of the two terms is the total capital of the enterprise in the next term .

The deposits that banks or other financial intermediary institutions obtain from common workers or young entrepreneurs will be either loaned to other domestic enterprises or used to buy foreign bonds. The model mentioned in the thesis presumes that banks or other financial intermediaries run in a completely competitive financial market, which means that interest rates on deposits are equal to the loan interest rate, i.e., the unit funds rate of return is r whether the deposits are used to provide a loan to domestic enterprises or to buy foreign bonds. What is more, it is presumed that the bank cannot provide a loan to domestic enterprises freely due to policy or incomplete information factors. Specifically, the bank sets the loan upper limit in proportion to the personal capital of the entrepreneurs, i.e., it meets the condition that , with the parameter referring to the financial constraints.

Since Enterprise S is not restricted by financial constraints, we will not consider its behavior for the moment. First, we use the reverse thrust of the two-step method to solve the following optimization problems. (1) On the basis of the given current capital inputs (the previous investment level determines the current capital inputs in the process of production), business owners can choose how to adjust the labor inputs and determine their wages, and corporate profits expression is derived. (2) Business owners decide the optimal investment level in the previous period on the basis of knowing the profit returns brought by different capital inputs. (3) While facing financial constraints in the market, business owners must improve their production efficiency in order to survive on a balanced basis in the market.

First of all, under the condition that the total amount of the corporate capital

is set, the corporate manager can choose the wage rate

and the number of workers

to achieve the maximum profit. Corporate owners will not quote wages higher than

in a relatively labor rich environment. The wages will not be lower than

. Therefore, the result is

. In this formula,

refers to the production function meeting their own small-scale production. As this production model only involves working for themselves, its purpose is to meet their own needs.

stands for capital tax. Aziz and Li [

77] hold that the role of capital tax on corporations levied by the government is the same as financial constraints. Considering that

F-type enterprises are subject to financial constraints

and the expenditure of technology efficiency

, the wages must meet both the needs of common workers and the company’s own constraints. What is more, both Enterprise

F and Enterprise

H are subject to financial constraints. Therefore, the optimization problem of the enterprise can be written as

Put Formula (11) into Formula (10) and it can be concluded:

Put Formula (12) into

, and it can be known that

Put Formulas (12) and (13) into Formula (10), and the profit expression can be drawn:

can be seen as the rate of the capital return corporate sectors, the specific form of which is:

Formula (15) clearly shows that the profit rate of the corporate sector is the increasing function of technical efficiency investment and the decreasing function of the financial constraints.

Part of the enterprise profit is taken as the remuneration of the corporate managers, namely . Therefore, the profit the corporate owners can obtain is , part of which must be paid to the bank, namely . Therefore, from the point view of the young entrepreneur (namely from the point of view of the manager in the t − 1 term), all of his deposit can bring him rate of return in the future. These can also be used for the loan from the banks. Only when does the young manager have motivation to continue to work in the next phase.

According to Formula (15), it can be known that when , . In this case—speaking exactly, the situation is expected—the young entrepreneurs will not deposit in the banks and other financial institutions. Rather, they will choose to invest in their own enterprises to conduct endogenous financing.

Furthermore, if the young entrepreneur spends deposits

on investing his own enterprises and obtain loans

from the bank, his income in the next phase is

. Shown by consumption, this is:

Also, when

, namely

, the entrepreneur will borrow as much money from the bank as possible. This meets the condition that

Put Formula (18) into Formula (19), and the following formula can be obtained:

Put Formulas (16) and (19) into Formula (1), and it can be obtained:

Combine Formulas (20) and (21) to solve the maximization of the objective function, and the Lagrangian can be written:

From its necessary first-order conditions, the deposit propensity function of the entrepreneur is as follows:

In which

is the saving propensity of the entrepreneur, which is as follows:

From the above contents, the transfer equation of intertemporal private investment can be obtained:

When

,

, so that when

, the following can be obtained:

, namely:

From the combination of Formulas (15) and (26), it can be known that exists. When , . To sum up, when and ,. Finally, it can be concluded from observation (25): and .

It can be known from Equation (19) that . At this point, the following two propositions can be obtained. Therefore, the more serious the financing constraint, the higher the production efficiency of F enterprise. When the financial constraints in the section are serious, Enterprise F must improve its efficiency in order to survive in the market. When , the young entrepreneurs can obtain savings in phase t by occupying workers’ remuneration in order to increase endogenous financing. They will invest all the capitals in their own enterprises. At the same time, they can also obtain the upper limit of the lendable funds through the bank. Under this condition, the savings propensity is higher than that of the common labor, i.e., . What is more, the savings propensity of entrepreneurs will increase with the increase of financial constraints. Thus proposition 1 is proposed.

Proposition 1. Corporate savings are positively correlated with financial constraints; corporate savings will rise as financial constraints increase.

Proposition 1 can be understood as follows. When the financing constraint intensifies, the saving tendency of entrepreneurs will increase. They tend to increase their savings by “crowding out” the remuneration of workers so as to achieve the purpose of endogenous financing to provide the next stage of production investment. In this case, the saving tendency of entrepreneurs will be greater than that of ordinary workers. Moreover, the propensity of entrepreneurs to save will increase with the increase of the expected return on capital of the enterprise sector in the future.

Further, when the financial constraint is serious, Enterprise F has to improve efficiency. When , the total output in the region will increase with the improvement of the needed efficiency . The ratio of the enterprise sector revenue to GDP is higher and higher, while the ratio of the income of the household sector to GDP is getting lower and lower. Thus proposition 2 is proposed.

Proposition 2. Labor income share is negatively correlated with financial constraints; financing constraints ultimately reduce the share of labor income by raising corporate savings.

Proof of proposition 2: From the model setting, we can know the expression of regional total output

from the model set. From the combination of Formulas (15) and (16) it can be known that:

Put Formula (27) into the expression of the total output, and Formula (28) can be concluded:

Throughout the process, the total income of ordinary workers is . From its combination with Formula (27) it can be known that the proportion of the income to the total capital output will decrease with the increase of . In addition, is the increasing function of . The proportion of the sum of entrepreneurs’ income and common people’s income to the total output is set as . When the proportion of common people’s income decreases, the proportion of entrepreneurs’ income increase.

Proportion 2 can be understood in this way. With the increasing financial constraints, the enterprise will improve technology efficiency in order to survive. The increase of employment will also lead to larger capital investment in itself. Hence labor will gradually shift from family-style production to large-scale production. Compared with the former production pattern, the latter one pays more attention to capital investment, and the corresponding proportion of labor income will become smaller and smaller. It also can be observed from Formula (15) that, when , the capital return rate of the corporate sector is higher than the savings return rate of common laborers r. What is more, with the increase of , the increasing speed of will be faster than the increasing speed of common workers’ wages. The combination will lead to a wider gap of income between the entrepreneurs and the common people.

7. Model Calibration and Fitting

Next, based on the theoretical model, we will make predictions through model calibration and fitting. The empirical results verify the view proposed in this paper based on the economic facts of China: that is, the imperfection of China’s financial market makes non-state-owned enterprises more inclined to use savings for “crowding out” workers’ remuneration for endogenous financing, thus increasing the savings rate and reducing the labor income share. Considering that financing constraint is the focus of China’s market-oriented economic transformation, we are concerned about whether, with the acceleration and completion of China’s economic transformation, after the improvement of China’s financing constraint, the declining trend of labor income share can be alleviated. Can a more equitable distribution be achieved?

Before discussing dynamic equilibrium, it is necessary for us to further explain S,and F enterprise based on the Chinese background. The difference between these three types of enterprises lies in their production efficiency and financing constraints. To be specific, S is a state-owned enterprise with low production efficiency, but it is not restricted by financing constraints. On the contrary, enterprises F are non-state-owned enterprises, and their production efficiency is relatively high, but they are restricted by financing constraints. Non-state-owned enterprises F have higher production efficiency because their property rights structure can improve their production efficiency, but it faces a credit market that is difficult to finance-this market is controlled by state-owned banks. As a result, the capital accumulation of non-state-owned enterprises F mainly relies on endogenous financing obtained by “crowding out” labor compensation. In contrast, although the production efficiency of state-owned enterprise S is low, it is easy to obtain exogenous financing from the credit market, which actually produces a completely different distribution effect.

It is assumed that

S enterprise,

F enterprise and

H enterprise all have positive employment in the economic transformation. Because enterprise

F and

H are subject to financial constraints, compared with enterprise

S, they choose a lower capital-output ratio in the equilibrium. To get a clearer picture of this idea, the capital output ratio is set as

(

i =

S,

F,

H), as

, so:

In the meantime, as from Formula (15) the capital output ratio can be concluded:

After observing Formulas (34) and (35), it can be known that .

The following section will consider the model equilibrium dynamics. There are two key variables.

and

are state variables. The effective labor to capital of the two enterprises

and

are constant numbers. The savings rate (

) of the entrepreneurs in phase t is linear to

. These three features mean that the employment, capital and output in the economy transformation period increase at the rate of constant numbers. In the equilibrium, the capital stock of enterprise

S is as follows:

Referring to the study by Song et al. [

5], we regard China’s economic privatization and financial liberalization as economic transformation. Formula (36) means that in the economic transformation period, Enterprise

S will employ all labor except that which is employed by Enterprise

F. It will realize a capital–labor ratio by adjusting

. Therefore, with the transformation of the economy, enterprise

H will withdraw from the economy. In the meantime, with the increase of the employment of enterprise

F,

will decrease constantly. In the transformation period, the total capital accumulation of enterprise

S is hump shaped. In the initial stage, Enterprise

F has a lower employment and

is increasing positively. However, with the transformation of the economy, the increase rate will decrease constantly, and finally turn to negative.

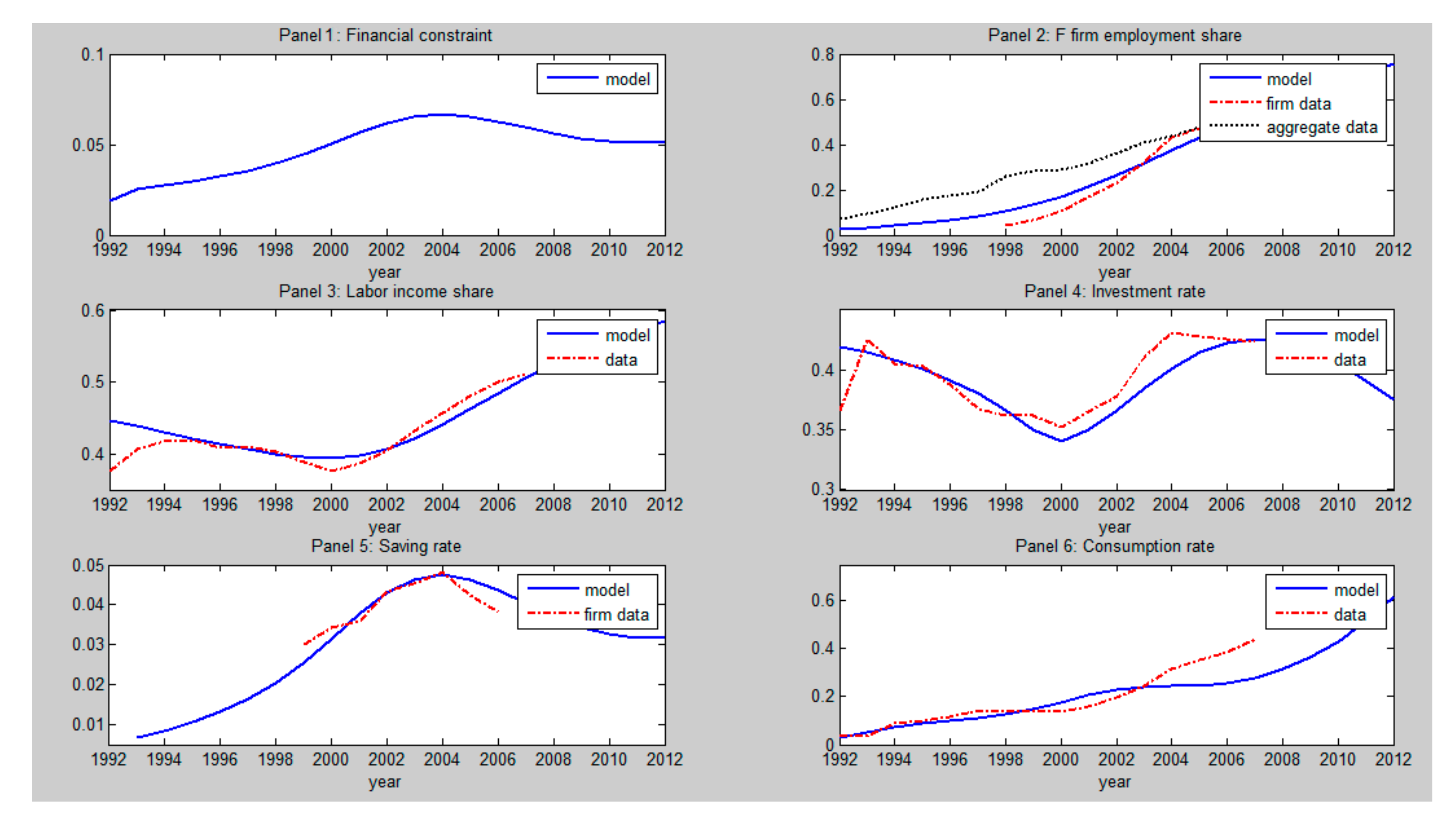

Figure 10 describes the transformation dynamic path of employment, wage, investment, labor income share, savings rate and foreign reserve. Due to the financial constraint, Enterprise

F can only obtain endogenous financing by occupying the laborers’ remuneration, which leads to the decrease of the labor income share. Thus, in the transformation, the labor income share is decreasing constantly (shown in Panel 3 of the

Figure 10). After the transformation, all laborers will be employed by Enterprise

F. In the transformation stage, the employment of Enterprise F will increase (shown in Panel 2 of

Figure 10). In the meantime, the total savings rate

(

) increases constantly (shown in Panel 5 in

Figure 10). The opposite investment rate

(

) will decrease (shown in Panel 4 in

Figure 10).

During the period of economic transformation, employment personnel are constantly allocated to F enterprise, and state-owned banks’ investment in S enterprise is constantly declining, which leads to a decline in the number of domestic loans. However, due to financial constraints, the number of loans to F enterprise is small. With the end of economic transformation, all the labor force is employed by F enterprise. With the continuous improvement of the financial market and the removal of financial constraints, F enterprise is no longer inclined to conduct endogenous financing by “crowding out” the remuneration of workers, and the savings rate will gradually decrease. In the stage of economic transformation, the continuous improvement of financial market will change the current situation in which non-state-owned enterprises mainly use endogenous financing. This is reflected in the increasing borrowing share of non-state-owned enterprises, because non-state-owned enterprises can make more use of exogenous financing. In this process, the proportion of the non-state-owned sector is increasing, and will absorb more and more resources; as a result, its returns are rising.

When the economic transformation is over and all labor is absorbed by the non-state-owned enterprise sector, the increase in its investment will lead to a decline in the investment rate (as shown in Panel 4 in

Figure 10). The exogenous financing proportion of non-state enterprises increases during the economic transformation will reduce the proportion of non-state enterprise endogenous financing, and lower funding costs will lead the saving rate of the non-state enterprises to drop year by year. The non-state-owned enterprises do not tend toward “crowding out” of laborers’ remuneration for endogenous financing. This will increase the share of workers’ remuneration in non-state-owned enterprises (Panel 3 in

Figure 10). Finally, the obvious result is that as financial markets mature, wages of non-state-owned enterprises will rise and their reduced dependence on endogenous financing will lead to a decline in the savings rate (see Panel 5 in

Figure 10).

Next, we turn to the prediction and numerical analysis of the model to explain the characteristics of China’s economy from 1990 to 2014. The model predicts well the high rise in China’s savings rate, the inverted U-shaped change of the investment rate, the U-shaped change of the labor income share, and the continuous increase in employment in the non-state-owned enterprise sector. Parameter settings are shown in

Table 6. The parameters are set as follows: one phase is one year, so that an individual, at the age of 28, will begin to work and then retire at the age of 78 (T = 50). In general, Chinese people work for 30 years and retire at the age of 58. The thesis presumes that r = 0.175, which refers to the one-year deposit rate between 1998–2005 (after deducting the CPI level). According to Bai et al. [

69], the capital share is set as 0.5 and the capital depreciation rate is

(World Bank Development Index report). Workers’ growth rate is v, and v = 0.03. Finally, the intertemporal elasticity of substitution is set as

. According to Song at el. [

5], the discount factor

.

Dynamic simulated economy based on the above parameter settings is shown in

Figure 10. Panel 1–Panel 6 is the data fitting of the key macroeconomic variables of the model. First, we simulate the financial constraints (see Panel 1 in

Figure 10); it can thus be seen that, with the massive restructuring of China’s financial system since the mid-1990s [

7], gradually tightening measures were taken(though the purpose of the reform was to strengthen credit efficiency first), the tendency of “centralization” appears in the financial sector [

8] which has accompanied the trend of decentralization in the real economy. Due to the lack of substantial progress in the financing environment of China’s financial market, financial institutions give priority to state-owned enterprises as the target of capital delivery, while the financing environment or financial constraints of non-state-owned enterprises have not been improved accordingly. Tighter financial constraints have led to a decline in China’s labor income share.

However, with the improvement of China’s financial market, the degree of financing constraint will be reduced. Second, the labor share in the model’s simulation is consistent with its decline since the 1990s and is U-shaped. In particular, the labor income share has fallen sharply since 2002, coinciding with a disproportionate rise in the saving rate (see Panel 3 in

Figure 10). Thirdly, compared with the actual employment, the simulated economy shows accelerated employment transfer and allocation (as shown in Panel 2 in

Figure 10). Finally, the total savings rate shows an inverted U-shape because our simulation here matches the average savings rate. The falling savings rate since the 1990s has been accompanied by China’s low consumption rate (see Panel 6 in

Figure 10). Financial constraints on non-state-owned enterprises led to an increase in the corporate savings rate, which ultimately contributed to China’s high savings rate. The year-on-year rise since 2000 has coincided with a steady decline in the labor share (see Panel 5 in

Figure 10).

From the analysis above, it can be seen that the important feature of the distribution mechanism of the model we constructed is that the existence of financial constraints makes it difficult for capital to flow to enterprises with high production efficiency, and they tend to conduct endogenous financing by “crowding out” workers’ remuneration. With the development of China’s economic transformation, the level of financial development continues to improve, financing constraints continue to ease, entrepreneurs can obtain exogenous financing at a lower cost, and are not inclined to financing through “crowding out” laborers remuneration, causing labor income share decline to ease or even increase.

Model calibration and quantitative prediction show that with the acceleration and completion of China’s economic transformation, China’s savings rate will reach its peak and then decline, while the labor income share will bottom out and rise.

8. Conclusions

The general decline in labor income share is one of the major problems confronted by the global economy today. This paper used firm-level micro-data to explore the reasons for the decline in labor income share from the novel perspective of financial constraints and corporate savings.

In theory, we review the typical facts of the Chinese economy, sort out the possible economic link between the rise in the savings rate and the fall in the labor share, and put forward the viewpoints to be tested. In other words, the existence of financial constraints in China’s imperfect financial market makes non-state-owned enterprises with higher efficiency more inclined to conduct endogenous financing by “crowding out” workers’ remuneration. This is the deep cause for the continuous decline of labor income share since the mid-1990s. Subsequently, based on the diamond model and overlapping generation model, a theoretical model is constructed to introduce financial constraints into the cost of obtaining credit. Proposition 1 and Proposition 2 are then proposed to be tested. Specifically, Proposition 1 is that corporate savings will increase with the increase of financial constraints, and Proposition 2 is that the share of labor income declines as financial constraints increase.

Empirically, based on data from the Chinese Industrial Enterprises from 1999 to 2007, the empirical research finds that, consistent with the theoretical Proposition 1 and Proposition 2, the existence of financial constraints in China’s financial market makes more efficient non-state-owned enterprises more inclined to conduct endogenous financing by “crowding out” workers’ remuneration. This is directly responsible for the steady decline in the labor share since the mid-1990s.

Finally, we carry on the numerical simulation and make a forecast whose results show that in the process of China’s financial market continuing to improve, the financing method of non-state-owned enterprises will gradually be transformed from endogenous financing to exogenous financing, so that enterprises’ “crowding out” labor remuneration will gradually disappear. This will further reduce China’s savings rate, and the labor income share will bottom out eventually.

These research results theoretically explain the imbalance phenomenon that rising savings rate is accompanied by declining labor income share from the perspective of financial constraints in China. The model calibration and fitting prediction show that with the improvement of financing constraints, the labor income share will stop falling and will rise. In the past four decades, the labor income share in the global macro primary distribution of national income has declined significantly [

2,

3]. This research provides a new possible explanation for the decline of the global labor income share. Considering the large impact of declining labor income share on income inequality [

40] and sustainable development caused by income inequality [

41,

42,

43], the empirical results of this paper provide empirical evidence and policy paths for other developing countries with imperfection financial markets [

65,

66] to carry out financial system reform, increase labor income share and promote sustainable economic development.

This paper is a preliminary study on how financial constraints reduce labor income share, and the impact of financial market imperfections on the economy is comprehensive. Credit constraints may also distort industrial structure and induce technological progress bias, and ultimately affect labor income share, which will be our future research direction. In the context of financing constraints in most developing countries [

65], this series of studies will help these countries speed up financial reform and promote sustainable economic development.