2.1. Supply Chain

For companies today, supply chain strategy has become more prominent in overall strategic plans: “the competitive advantages from an adequate Supply Chain Management are hardly imitable” [

18]. Thus, developing and maintaining constructive relationships with suppliers is a determinant of the competitive position and financial sustainability of companies. Van Weele [

19] defines supply chain management as “the management of all activities, information, knowledge and financial resources associated with the flow and transformation of goods and services from the raw materials suppliers, component suppliers and other suppliers, in such a way the expectations of the end-users of the company are being met or surpassed. “For Christopher [

20], supply chain management is the “management of relationships upstream and downstream with suppliers and customers to deliver a higher value to the customers at a lower cost to all supply chain” [

18].

The electronic era is completely present in the current business world, and purchases are no exception. This may be in the form of supplier search and contact, but more importantly, the company–supplier relationship. Van Weele [

19] argues that electronic networks are a key success factor in most companies and that easy access to information by both parties is highly valued. The same author supports Håkansson [

21] and Wijnstra (1998, as cited in Van Weele [

19]) on the learning relationship between suppliers and producers, which is not only influenced by the characteristics of goods or services being produced or provided but also by the relationship between both organizations and between the other parts of the supplier network.

Regarding consumption patterns, there are big differences between B2B and business-to-consumer (B2C) customers. In the B2B environment, the buying group is complex, being different in each organization and with different roles [

21]; the B2C environment, however, is much simpler and depends on a small number of individuals, sometimes even depending on a single individual. Relationships differ in these two environments in that B2B long-term relationships between supplier and customer require continuous relationship management, which usually proves to be a success factor [

22]. In addition, for successful supply chain collaboration, sharing resources and knowledge about internal activities and market insights is crucial [

23]. However, both B2B and B2C have evolved, and the value concept has expanded out of the quality-price relationship, and there are many other buying decision factors, such as convenience, after-sales service, dependency, singularity, and customization [

19]. This enlargement of requirements made producers continuously look for opportunities that would allow them to reduce costs and/or improve efficiency, while at the same time, innovate their offerings as upstream collaborations—a great opportunity that can be even more profitable than downstream [

24]. Thus, the main idea behind collaborative relationships is to address market demand by examining market behavior [

23] and developing solutions as needed. However, there are different views on this issue. One of the results that Kumar [

23] finds with his recent study is that a highly collaborative downstream relationship is not always profitable to the company.

As mentioned above, purchases play an important role in the supply chain. According to Van Weele [

19], “the management of the company’s external resources in such a way that the supply of all goods, services, capabilities, and knowledge, which are necessary for running, maintaining, and managing the company’s primary and support activities, is secured at the most favorable conditions.” However, Van Weele [

19] states that planning and programming of resources, stock management, inspection, and quality control should be interconnected with purchases in the best possible way, and the buyer should support these activities as indispensable to reach efficiency. However, all of these tasks are difficult to fulfill [

23], and the differences among organizations, along with the need for them to collaborate, are also a challenge [

23]. Van Weele [

19] notes that supply chain-related terms, such as buying and supply, have different meanings in the management literature. For example, there are clear differences in the use of the term supply in Europe and America: “In America, ‘supply’ covers the stores function of internally consumed item such as office supplies, cleaning materials, etc. However, in Europe, the term supply seems to have a broader meaning, which includes at least purchasing, stores, and receiving” [

19]. Therefore, a supply strategy should refer to the number of suppliers the company has for each category, the type of relationship with each one, and the type of negotiations to be carried out. Buying management refers to all activities needed to manage the suppliers’ relationships, with a focus on the structure and the continuous improvement of processes both inside the organization and between the organization and its suppliers. Van Weele [

19], regarding buying management, argues that if suppliers are poorly managed by the customers, those relationships will be managed by the suppliers. In other words, the buying policies of an organization impact its success in various ways, being able to improve sales margins by efficient cost savings, better deals with suppliers regarding quality or logistics, and even innovate its products/services portfolio through suppliers’ inputs. Being able to work with more competitive suppliers and develop strong relationships with them must be one of the core tasks of the buyer because it will leverage the competitiveness of the organization, once “these lasting relationships also form a barrier against supplier’s competitors getting into contact with the customer” [

19], which would benefit both the company and the customer. At present, it is still essential that a buyer is capable of having a global approach in the search and the relationship with suppliers, being able to communicate with different cultures, and negotiate in different languages. Moreover, there is a significant increase in the organization and their final customers’ demand for environmentally and socially sustainable policies [

5].

The buying process encompasses a variety of goods that can be categorized as follows: raw materials, supplementary materials, semi-produced products, components, commercial or finished products, investment goods or capital equipment, maintenance materials, repair, and operations and services [

19]. The author also categorizes the buying processes in three types: “the new-task situation,” “the modified rebuy,” and “the straight rebuy”. Most purchases are “straight rebuys”—repeat purchases from the same suppliers—with the lowest risk of all the purchase types. Some factors increase risk, such as the novelty factor, an increase in the value of the purchase, an increase in technical complexity, and an increase in the number of people involved in the process [

19]. Nonetheless, the buying process must be well organized among the buying group, minimizing possible problems, because “the strategic management of purchases has a positive impact on financial performance in big and small companies (Carr and Pearson, 2002)” [

18].

The fact that buying groups are so diversified and extensive in B2B means that the roles encompassed in them are not limited to the buying department [

21]. This department is especially responsible for operational tasks, such as quote requests and placing orders, but many other departments are involved according to their functions in the organizational framework [

22]. However, organizations should be aware that the administrative burden given to the purchasing department can reduce the time spent on strategy and tactics essential to success [

19]. Holmberg [

25] argues that companies that successfully implement supply chains think about them strategically and look for a high volume of sales (more value to the customer), better use of assets, and reduction in costs. “Bowersox et al. (2003) say that it is expected ‘to obtain competitive superiority as a result of a precise resource allocation that generates scale economies, reduces redundant and duplicate operations, and increases customer loyalty through a personalised service” [

18]. Therefore, it is important to understand the four main dimensions of the purchasing functions [

19]: technical, commercial, logistical, and administrative. The first is in charge of determining aspects such as the specifications of the goods and services that are to be purchased, select the suppliers and draw up contracts, while auditing supplier’s organization, value and quality control. The second, the commercial dimension, is in charge of conducting research of the supply market, receiving supplier visits and requests, and evaluating and negotiating quotations to and from suppliers. The third, the logistical dimension, is responsible for optimizing the ordering policy along with inventory control, expediting order and follow-up, and inspecting incoming products and monitoring delivery reliability. Finally, the fourth and last dimension, the administrative, oversees handling and filling, checking non-marketing supplier invoices, as well as monitoring payments to suppliers.

Thus, for efficient management of the supply chain, it is necessary to have “a concertation with involved partners (…) (customers, suppliers, logistic services providers, etc) and a greater capacity to integrate information and planning” [

18]. Moreover, companies capable of this successful integration of the supply chain “have demonstrated a superior performance” [

18].

2.2. The Sustainable Supply Chain and Its Impact on Purchasing Policies

In 1987, the concept of sustainable development was mentioned in the World Commission on Environment and Development report “Our Common Future” [

2]. The concept was defined as the satisfaction of the necessities of the current time without compromising the satisfaction of future generations’ necessities. This kind of economic growth is only possible with a proper connection between technology and social organization, being perceived as a changing process and not a fixed state [

2]. This is because sustainability requires a balance between social, environmental, and economic interests [

26]. The triple bottom-line approach, developed by John Elkington in 1994, corroborates the abovementioned discussion by giving great importance to social and environmental impact as well as profit [

27]. Later, Elkington [

27] redefined the three dimensions as people, planet, and profit. With the growing awareness of how human activity impacts climate change, much research has been conducted on sustainability, green marketing, ecology, environment, and pollution [

4,

8,

9,

10,

11].

There has been growth in the importance of green topics in research, showing that marketing and communication should induce more responsible consumer and producer behaviors. In the agri-food industry, concepts such as quality are being “surpassed and replaced by the concept of sustainability, in environmental, social and, of course, economic terms” [

24]. This action highlights the importance of corporate social responsibility on consumers’ perceptions and on corporate performance, which, in turn, impacts their emotions and ecological commitment [

4]. “It is often repeated that consumer demand is the impetus behind green supply chain development (e.g., Carter and Carter, 1998; Bhaskaran et al., 2006; Grunert et al., 2014). Research into factors predicting green supply expectations finds that a consumer’s lifestyle (e.g., consumption style and green commitment) may play a greater role than demographic profile (Haanpää, 2007; Penaloza and Mish, 2011). Moreover, motivation often plays a key role in determining the comprehension of a specific eco-label’s meaning, as both motivation and understanding are significant predictors of eco-label usage (Grunert et al., 2014)” [

28].

However, recent data from the State of Supply Chain Sustainability 2020 [

29] report notes a significant mismatch between both sides of the sustainable supply chain: social sustainability is the “top of mind” goal, but environmental sustainability goals receive more investment. Meanwhile, Bager and Lambin [

30] conclude that companies are more dedicated to adopting socio-economic practices than environmental ones. Notwithstanding, the sustainable approach based on the three pillars has seen global growth. For example, the recycling trend redirected some consumption to certain brands, products, and materials. In this way, a sustainable behavior program that benefits both customers and the environment can generate more satisfaction for the program than only for personal benefit [

4]. Nevertheless, it is necessary to consider that the implementation of a sustainable supply chain is a transformative task that involves organizational learning [

1]. Therefore, companies make commitments toward sustainable management (through adequate strategies and institutional structures) that lead to sustainable development [

7] and make efforts to adapt their sustainability practices to each stakeholder, once each one could have varying degrees of sustainability issues across their network or be influenced by the local sustainability issues in which they operate [

30].

Focusing on the supply chain, since the supply chain involves all activities connected with goods and services transactions, there are factors (e.g., legislation and regulations, ethics, stakeholders pressure, and economic opportunity) that also contribute to the concern and importance of sustainability [

31] that should be reviewed in a more sustainable way. For example, in 2019 the products labeled as “farm to table,” “fair trade,” and “ethically sourced” saw growing sales, with an estimated annual growth of 7% until 2025 [

29]. In addition to these labels, product innovation through collaborations between companies and suppliers, such as biotechnology companies, have helped to address the risk of dependence on key customers [

24] and thus prevent a price war with competitors.

According to the Industrial Marketing and Purchasing (IMP) interaction approach [

22,

32,

33], the focus must be on the various actors of the network without any assumption, regardless of the control of any actor over the others or about their centrality. Instead, we should try to understand how companies commit to sustainability through their supply chains [

34]. Håkansson and Ford [

35] mention that attempts to control networks might reduce their effectiveness. However, companies should know their supply chain and try to influence direct and indirect suppliers in various locations where sustainability comprehension is weak. Furthermore, we can argue that a sustainable supply chain is essential for competitiveness in current times. Its creation is dependent on both internal and external operations of the organization, with the latter being more impactful (as the supply chain and network) owing to the strong influencing power the organization has toward its suppliers and customers. Proença and Santos [

36] argue that most sustainable practices among companies are related to activities and resources that involve learning processes that can leverage and develop relationships that still do not exist in the current business network. Furthermore, top management is essential in this process, as they must spread and teach the mission and vision through the entire company, as supply chains are cross-disciplinary and cross-functional [

1], involving a great number of people and collaborations. Additionally, three approaches are presented that can help companies make their supply chains more sustainable. These include identifying critical problems in the supply chain (e.g., coffee plantations may tend to hire underage workers to grow and harvest coffee), linking the supply chain sustainability goals of the company with the global sustainability agenda, and helping suppliers manage their impact [

37]. Beamon [

38] argues that to accomplish a green supply chain, organizations must follow the principles of ISO 14000 (norms and guidelines for environmental sustainability businesses). The first step is to rethink the current structure (which is usually unidirectional) towards a closed loop that includes supply chain operations at the end of the product lifecycle and packaging recovery, collection, and reuse (through recycling and/or remanufacturing). Thus, environmental concerns must always be a focus to marketers at the industrial and regulatory level and packaging, which, for example, should be ecological [

4]. “Specifically, sustainable supply chain management involves the integration of environmentally and financially viable practices into the complete supply chain life cycle, ranging from product design and development to materials selection (including raw materials extraction or agricultural production) manufacturing, packaging, transportation, warehousing, distribution, consumption, return, and disposal” [

28].

The integrated supply chain contains all elements of the traditional one (which usually is unidirectional, as follows: Supply → Manufacturing → Distribution or Retail → Consumer). However, the integrated supply chain also includes recycling, reuse and/or remanufacture processes and operations of both products and packaging, with a clear focus on sustainability [

28].

Within our scope, it is also important to understand that a sustainable supply chain must include sustainable purchasing policies. According to Hasan [

39], green purchasing can be based on two components: the environmental performance evaluation of the suppliers and the willingness to help suppliers improve their performance. Those responsible for purchases and the supply chain are in a strategic position to influence the size of the company’s environmental footprint, namely, with the selection and evaluation of suppliers, relationship development, and purchasing processes. This means that they can have a big impact on the capacity of the company to stand out and maintain competitive advantages by reducing costs, strengthening ties with customers, and creating a positive reputation in the market.

There is still the concept of green procurement (associated with green purchasing), which refers to a set of organizational practices to efficiently select suppliers with technical capabilities, eco-design, environmental performance, and that can support the environmental goals of the company [

40]. In summary, green procurement is the integration, in a company acquisition and buying criteria, of environmental and social concerns beyond economic ones. Nonetheless, the implementation of sustainable practices requires new activities and/or resources, involving different staff of various functions and probably of various new business relationships and organizations [

5].

The practical implementation guide of sustainable procurement, published by the Business Council for Sustainable Development (BCSD Portugal) [

41], states that there is not a single path to achieve a sustainable procurement process in an organization. However, there are five common elements among the successful programs: (i) define and disseminate the sustainable purchasing policy; (ii) involve the organization; (iii) establish measurable objectives and goals; (iv) identify the priority products/services and evaluate the impacts and risks associated with them; and (v) build partnerships with suppliers.

In addition, the use of smart technologies and tools, such as the Internet of Things, remote sensing, and blockchain, have the potential to develop sustainability [

42], particularly the use of blockchain to ensure traceability of raw materials, materials, products, and processes [

43]. However, the use of such technologies should not reduce the amount of contracted labor in order to be sustainable from a social point of view.

In this way, focusing on the coffee sector, the development of a sustainable supply chain and a respective purchasing policy, ideally, should follow the recommendations based on the literature, focusing importantly on its adaptation to the coffee industry.

2.3. Sustainability in the Coffee Industry

Coffee is one of the most consumed beverages in the world, with significant importance on the daily routines of many people. Thus, it has a significant social and environmental impact. Approximately 90% of world coffee production comes from 45 developing countries, involving 25 million farmers, and employing more than 100 million people. This is associated with a very complex global coffee supply chain which involves: producers, commodity traders, mill, transport, exporters, shippers, brokers, importers, roasters, packagers, distributors, and end consumers [

44]. However, to date, few studies have focused on sustainability practices in the coffee industry with special attention to the supply chain. Our literature review leads us to Nguyen and Sarker’s [

45] research with an interesting approach to sustainable coffee supply chain management—involving viewpoints of all related stakeholders—where they state that the coffee sector is facing enormous challenges influencing sustainable supply chain management. Bager and Lambin [

30] concur, arguing that even though actors have ambitious commitments addressing sustainability, our knowledge remains incomplete, and despite the long journey, only a few progressive companies are leading the way.

Although sustainable production is a relatively recent concern in the coffee industry, there is a growing number of customers willing to buy certified sustainable coffee [

45]. Certified coffees focus on at least one facet of sustainability, and there is evidence that they increase the profitability of coffee farms, with the most common certifications being Organic, Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance, Bird Friendly, UTZ, Starbucks C.A.F.E. Practices, and 4C [

45]. Nguyen and Sarker [

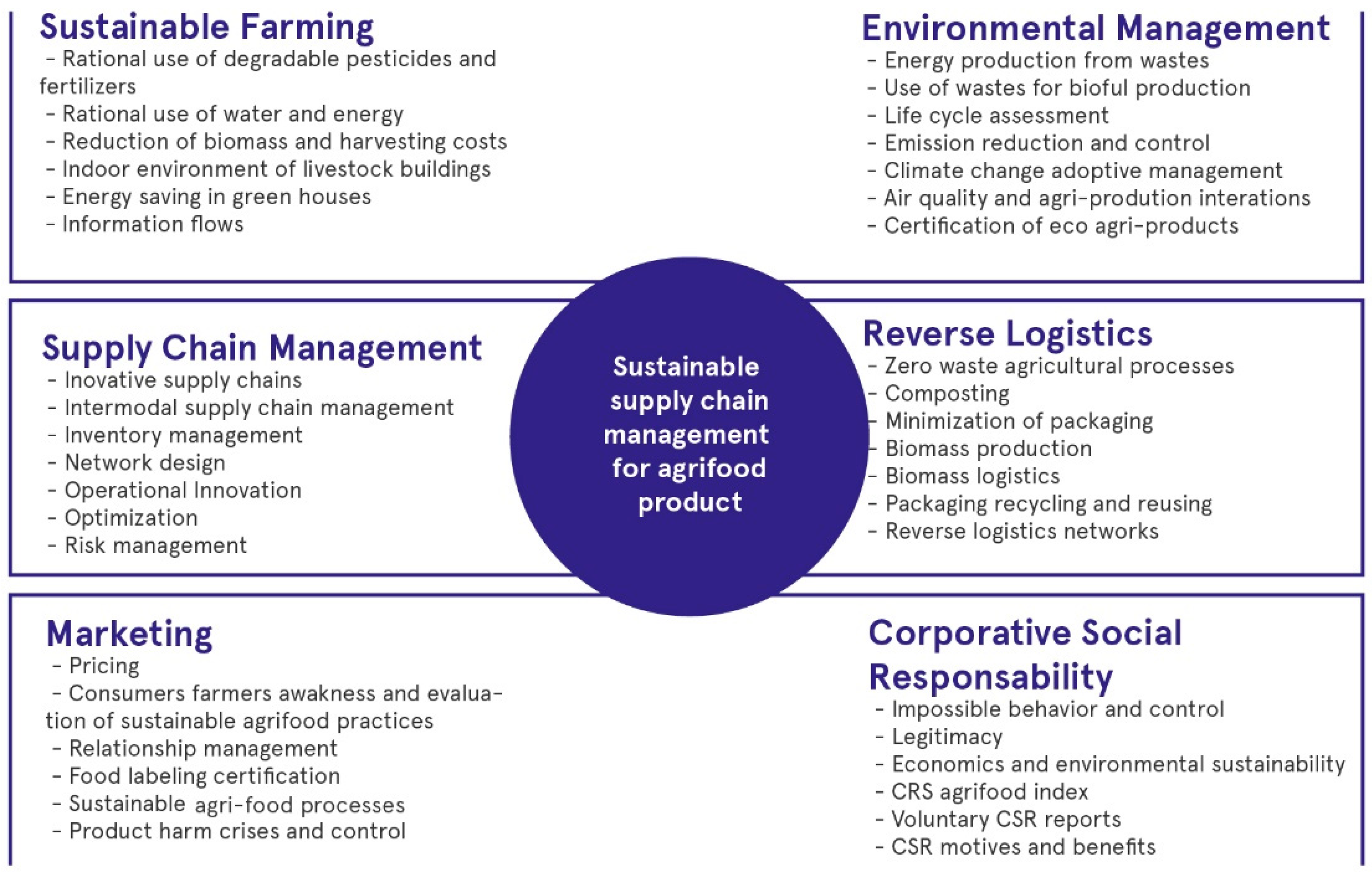

45] propose a holistic approach to a more sustainable coffee supply chain that encompasses six main factors influencing sustainability in the agri-food sector: sustainable farming, environmental management, supply chain management, reverse logistics, marketing, and corporate social responsibility (

Figure 1). This tool should be considered and used to adapt to the goals of each organization.

According to the literature review, we can conclude that corporate social responsibility and the focus on sustainability might not have an immediate visible impact. Nevertheless, it influences relationship management, increases customer satisfaction and confidence, efficiency, quality of life, and innovation promotion [

4,

27,

35,

39,

44,

45].

2.5. The ARA Model as an Important Tool to Analyze Sustainable Supply Chains and Purchasing Policies

The ARA model was developed by Håkansson and Johanson [

48] and Håkansson and Snehota [

22]. This model identifies interactions in business networks according to three elements: actors, resources, and activities (ARA). The three entities relate to each other not only using key aspects of relationships between organizations, but also at all levels inside the organizations, including the relationships among individuals [

49]. The ARA model represents a crucial tool for conceptualizing B2B relationships, and it aids understanding of how networks and supply chains may merge or connect at different levels of a company’s sustainable purchasing policies. Therefore, it is important to be aware of the main role of each element.

Actors can be individuals or collectives of people, such as groups, parts of companies, or companies, and are those who carry out activities or control resources. Actors invest and develop relationships with other actors to access, use, and combine resources to enhance the performance of their activities [

50]. These activities are usually performed with other actors involved (due to the relationship developed), with the main purpose of reaching strategic goals to benefit the organization or networks of organizations of which they are a part [

49].

Resources are available as heterogeneous means used by actors to achieve goals throughout activities [

50]. They can be tangible or intangible, meaning they can be raw materials, facilities, human knowledge, experience and skills, operating systems, etc. Combined with other resources, they can be increasingly valuable because the connection to activities (developed by all actors involved that have relationships bonds) leads to new knowledge and more opportunities [

50,

51]. Because of this, resources can be changed, developed, reused, and recombined in networks, and it is an interaction process that creates value for all parts involved [

51].

Activities bring life to businesses and their networks They can arise from different departments in an organization, such as producing goods, processing information, paying bills, providing services, etc., aiming to create all kinds of different effects and promote better relationships between all parts involved. The activities are influenced by actors and resources at any level of the organizational network, so any change creates different impacts [

49,

50,

51]. Hence, the ability of companies or actors to adapt their activities, using their resources, to other strategic organizations or partner structures is crucial. This enables the design of activities that would help achieve the outcomes needed to reach the ultimate goals [

50]. Therefore, it is fair to say that activities are interdependent, being part of an interactive ecosystem that involves actors and resources in the business landscape.

In summary, it is important that the ARA model perspective plays a key role in business relationships and commitment between counterparties [

22,

48]. Applied to our study, this approach aids in understanding how these three entities work together, giving us a holistic view of how the organization works to achieve a sustainable supply chain and green purchasing policy.