What Can Motivate Me to Keep Working? Analysis of Older Finance Professionals’ Discourse Using Self-Determination Theory

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundations: Self-Determination Theory

3. Method

4. Results

4.1. Need for Autonomy

I will slow down or stop within the next year because it’s clear that I don’t want to continue working at 110%. If the organization allows me to slow down, I’ll take it. I’d like the chance of teleworking, not being compelled to be physically in my office. If the organization can’t meet this need, I’ll have to find a solution elsewhere. (Respondent 11, M, 62 years old, older worker)

When you’re at the end of your career, you should not put all your eggs in that career because there are other things afterward. If your employer doesn’t give you this balance, I think it could be rather tricky. Keeping a work-life balance is a significant success condition; the only one I ask for (...) Yes, we work hard and give it our all, but your life isn’t your job. You need balance, and your employer needs to accept this. If my employer does not take this, I will quit. (Respondent 3, F, 53 years old, older worker)

An important part of employee retention is work-family balance. Young people look for flexibility because their child is in daycare and then at school. For older people, work-family balance is sometimes with an older spouse who is sick and needs care. It varies a lot with age. (Respondent 1, M, 51 years old, older worker)

Since last year, I’ve got a new job that’s a little less demanding. Before, I used to work six days a week. I’ve been given a less demanding job [...], but I’ve still got an interesting challenge, and I’m still learning. (Respondent 13, M, 60 years old, older worker)

If I’m given an interesting challenge with a good work-life balance, and I can enjoy it, I’ll stay. (Respondent 3, F, 53 years old, older worker)

Salary is an incentive because it’s commission-based. If you produce less, your commission percentage is reduced. The more you produce, the higher your percentage. If people start spending more time with their families, their income is reduced. It could be they no longer meet basic scales, and their salary is considerably reduced. In other words, they self-remove: if they don’t work, they don’t meet the minimum standards. (Respondent 7, M, 51 years old, older worker)

For the 15 last years, bonuses have increased overall compensation. This helps retain workers. I would demand a retention bonus to stay longer. I would not stay on any terms. (Respondent 13, M, 60 years old, older worker)

You’ve got insurance for dental care, healthcare, travelling, etc. Many people travel, and they want travel insurance when they’re 62-63 years old. They will lose it when they retire. (Respondent 1, M, 51 years old, older worker)

Employees have generous pension plans in large financial institutions that ensure a comfortable retirement. So, they remain at their job to benefit from its pension plan. (Respondent 15, M, 61 years old, older worker)

4.2. Need for Competence

The Human Resources department offered many training courses regarding competence levels, management, etc. Even at 57-58 years of age, we had access to training programs, just like all staff. (Respondent 16, F, 60 years old, older worker)

I’m lucky in that I have access to training programs. I try to keep informed so that I don’t feel out of touch. (Respondent 6, F, 55 years old, older worker)

I would have liked to have the opportunity of looking at feasible ways of working a few more years. I was willing to continue, but this type of discussion wasn’t available, and I would have liked to have it. (Respondent 10, M, 56 years old, transitional worker)

It is necessary to put in place programs that enable people to say, “I wish to slow down my professional activities while remaining active in the organization.” (Respondent 15, M, 61 years old, retiree)

Since last year, I’ve got a new job that’s a little less demanding. Before, I used to work six days a week. I’ve been given a less demanding job [...], but I’ve still got an interesting challenge. I’m still learning. (Respondent 13, M, 60 years old, older worker)

Sometimes, people can no longer keep up, and if it’s noticed early enough, the situation may be dealt with, and the persons can be directed toward something more suitable for them.(Respondent 6, F, 55 years old, older worker)

I think the possibility of gradually subdividing a position should exist. I could have worked four days a week. Anyhow, resigning was the only way I could manage. They freaked out because I had not given prior notice. I asked to slow down one year before. [..] I asked to slow down, to reduce my duties. I asked to work part-time, but they refused. I left.(Respondent 4, F, 56 years old, retiree)

Regardless of the job you’ve got, if your talent isn’t being used, the countdown has started before you leave, change jobs, or retire. If you’re not put in positions where you can use your talent, you’ll start thinking of retiring. (Respondent 5, F, 53 years old, older worker)

I could have stopped working five years ago [...], but I continue working for pleasure, not by financial obligation. I want to continue. It’s what I’m asked to do that keeps me at work. (Respondent 11, M, 62 years old, older worker)

4.3. Need for Relatedness

I left because of some misunderstanding with a new manager. I had a new manager, and we could not get along. We both agreed about my quitting, but it was unwanted and unplanned. (Respondent 10, M, 56 years old, transitional worker)

I did not get along with the person who took over the supervision of my group. There were personality conflicts. My old “gang” tried to retain me, to persuade the boss. But what happened, happened. (Respondent 14, M, 65 years old, transitional worker)

It’s more the issue of wanting to be useful, to do and accomplish something. To be useful is important. What makes me want to continue is to make myself useful, to serve a purpose. (Respondent 9, F, 57 years old, older worker)

When you get to a certain age, the most important thing is to feel useful to society. That’s what encourages me to continue working. (Respondent 12, M, 63 years old, older worker)

I am combining freedom and pleasure. I think it’s an interesting period in one’s life. If I can remain healthy and enjoy things, travel a little, and then at the same time be useful because I still want to serve society, to find value. For me, that’s the ideal way to retire. It doesn’t mean doing nothing but doing something else. (Respondent 9, F, 57 years old, older worker)

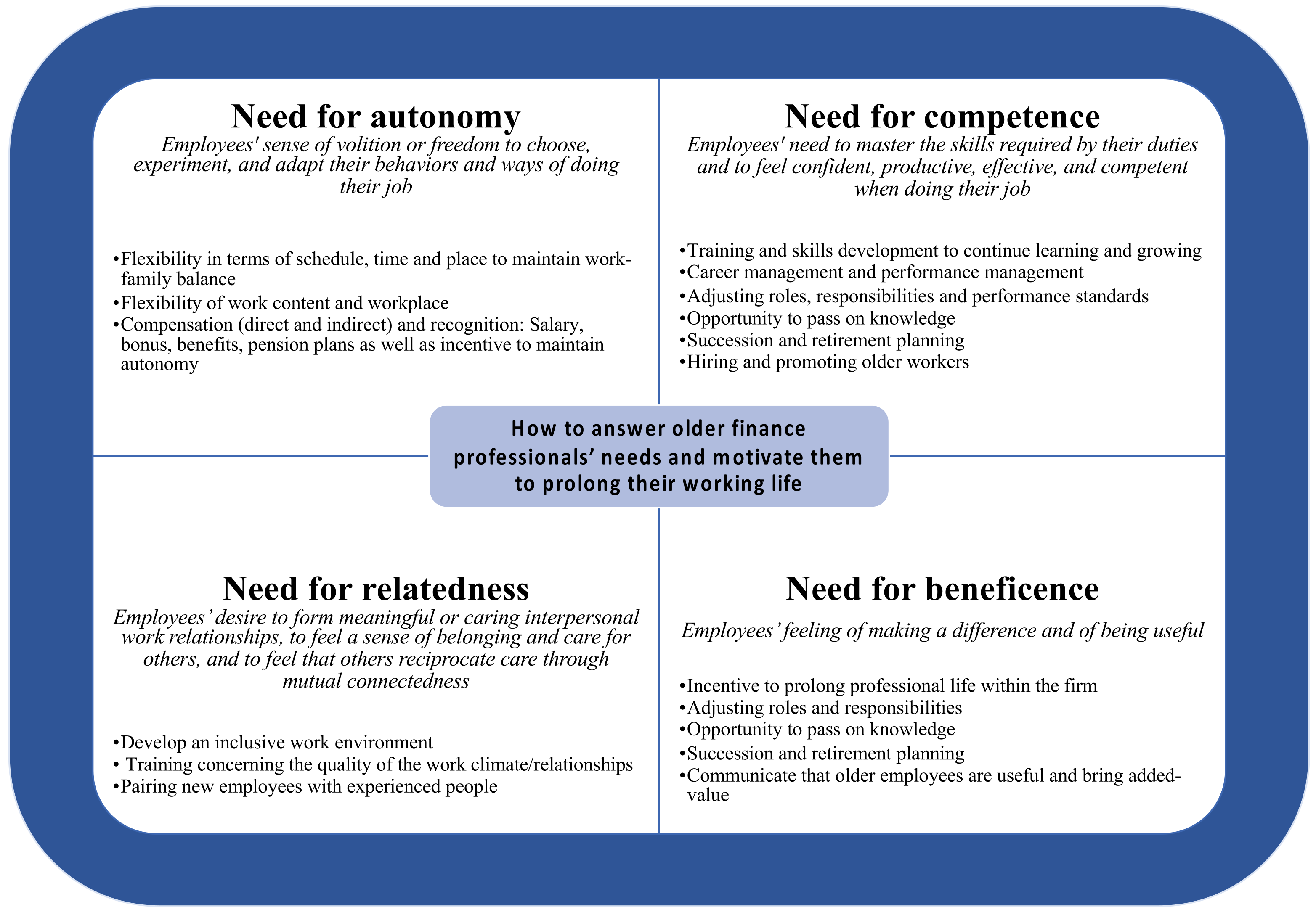

5. Discussion

5.1. Meeting Older Employees’ Autonomy Needs through Flexibility and Compensation

5.2. Meeting Older Employees’ Competence Needs through Skills Development and Use

5.3. Meeting Older Employees’ Relatedness Needs through an Inclusive Culture, Work Climate, or Supervision

5.4. Meeting Older Employees’ Beneficence Needs through Self-Realization and the Sense of a Broader Purpose

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statistics Canada. Population Trends by Age and Sex, 2016 Census of Population. 2016. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627- (accessed on 20 March 2018).

- Latulippe, D.; St-Onge, S.; Gagné, C.; Ballesteros-Leiva, F.; Beauchamp-Legault, M.-È. Le prolongement de la vie professionnelle des Québécois: Une nécessité pour la société, les travailleurs et les employeurs? Retraite Société 2017, 3, 45–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, T.; Bal, P.M.; Jansen, P.G. How do development HR practices contribute to employees’ motivation to continue working beyond retirement age? Work Aging Retire. 2017, 3, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bal, P.M.; de Lange, A.H.; Van der Heijden, B.I.J.M.; Zacher, H.; Oderkerk, F.A.; Otten, S. Young at heart, old at work? Relations between age (meta-) stereotypes, self-categorization, and retirement attitudes. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 91, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pak, K.; Kooij, D.T.; De Lange, A.H.; Van Veldhoven, M.J. Human resource management and the ability, motivation and opportunity to continue working: A review of quantitative studies. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2019, 29, 336–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, A.; Carrière, Y.; Sabourin, P. Understanding employment participation of older workers: The Canadian perspective. Can. Public Policy 2016, 42, 94–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchley, R.C. A continuity theory of normal aging. Gerontologist 1989, 29, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulik, C.T.; Ryan, S.; Harper, S.; George, G. Aging populations and management. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 929–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, D.-G.; Genin, É. Aging, economic insecurity, and employment: Which measures would encourage older workers to stay longer in the labour market? Stud. Soc. Justice 2009, 3, 173–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Armstrong-Stassen, M.; Schlosser, F. Perceived organizational membership and the retention of older workers. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 32, 319–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Truxillo, D.M.; Cadiz, D.M.; Hammer, L.B. Supporting the aging workforce: A review and recommendations for workplace intervention research. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2015, 2, 351–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, R.L.; Nyce, S.; Ritter, B.; Shoven, J. Employer concerns and responses to an aging workforce. J. Retire. 2019, 6, 82–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooij, D.T.; Jansen, P.G.; Dikkers, J.S.; de Lange, A.H. Managing aging workers: A mixed methods study on bundles of HR practices for aging workers. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 2192–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Canada. Système de Classification Des Industries de L’Amérique du Nord (SCIAN) Canada 2012. 2018. Available online: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3VD_f.pl?Function=getVD&TVD=118464&CVD=118465&CPV=52&CST=01012012&CLV=1&MLV=5 (accessed on 20 March 2018).

- Manpower Group. Solving the Talent Shortage. 2015. Available online: https://go.manpowergroup.com/hubfs/TalentShortage%202018%20(Global)%20Assets/PDFs/MG_TalentShortage2018_lo%206_25_18_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2017).

- Crosman, P. How artificial intelligence is reshaping jobs in banking. Am. Bank. 2018, 183, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Langlois, G.; Féral-Pierssens, L.; Leduc, M.-C.; Vézeau, N.; Tagnit, S. Impact de l’intelligence Artificielle sur le Secteur des Services Financiers. 2017. Available online: https://www.finance-montreal.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Finance-Montreal_Rapport-de-l%C3%A9tude_vFINAL.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2019).

- St-Onge, S.; Magnan, M.; Vincent, C. The digital revolution in financial services: New business models and talent challenges. In Handbook of Banking and Finance in Emerging Markets; Nguyen, D.K., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham/Camberley, UK, 2022. (In press) [Google Scholar]

- Lagacé, M.; Terrion, J.L. Gestion des travailleurs âgés: Les stéréotypes à contrer. Gestion 2013, 38, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, S.E.; Rook, M.L. Using a total rewards strategy to support your talent management program. In The Talent Management Handbook; Berger, L., Berger, D., Eds.; McGraw Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 343–357. [Google Scholar]

- St-Onge, S. Gestion de la Rémunération: Théorie et Pratique, 4th ed.; Chenelière Éducation: Montréal, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Worldat Work. The Worldat Work Handbook of Compensation, Benefits and Total Rewards: A Comprehensive Guide for HR Professionals; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Olafsen, A.H.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The ’What’ and ’Why’ of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cooman, R.; Stynen, D.; Van Den Broeck, A.; Sels, L.; De Witte, H. How job characteristics relate to need satisfaction and autonomous motivation: Implications for work effort. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 46, 1342–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, E.; Bailey, T.; Berg, P.; Kalleberg, A.L.; Bailey, T.A. Manufacturing Advantage: Why High-Performance Work Systems Pay off; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Boxall, P.; Purcell, J. An HRM perspective on employee participation. In The Oxford Handbook of Participation in Organizations; Wilkinson, A., Gollan, P., Marchington, M., Lewin, D., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 29–51. [Google Scholar]

- Van De Voorde, K.; Paauwe, J.; van Veldhoven, M. Employee well-being and the HRM–organizational performance relationship: A review of quantitative studies. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2012, 14, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, F.; Riekki, T.J.J. Autonomy, competence, relatedness, and beneficence: A multicultural comparison of the four pathways to meaningful work. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gagné, M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and work motivation. J. Organ. Behav. 2005, 26, 331–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gagné, M.; Forest, J.; Gilbert, M.H.; Aubé, C.; Morin, E. The motivation at work scale: Validation evidence in two languages. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2010, 21, 628–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-Determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vallerand, R.J.; O’Connor, B.P. Motivation in the elderly: A theoretical framework and some promising findings. Can. Psychol. Psychol. Can. 1989, 30, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Church, A.T.; Katigbak, M.S.; Locke, K.D.; Zhang, H.; Shen, J.; de Jesús Vargas-Flores, J.; Ibáñez-Reyes, J.; Tanaka-Matsumi, J.; Curtis, G.; Cabrera, H.F.; et al. Need satisfaction and well-being: Testing self-determination theory in eight cultures. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2013, 44, 507–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Hannon, P.A.; Laing, S.; Kohn, M.J.; Clark, K.; Pritchard, S.; Harris, J.R. Perceived workplace health support is associated with employee productivity. Am. J. Heal. Promot. 2015, 29, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeCharms, R. Personal Causation: The Internal Affective Determinants of Behavior; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Van Den Broeck, A.; Ferris, D.L.; Chang, C.H.; Rosen, C.C. A review of self-determination theory’s basic psychological needs at work. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1195–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olafsen, A.H.; Niemiec, C.P.; Halvari, H.; Deci, E.L.; Williams, G.C. On the dark side of work: A longitudinal analysis using self-determination theory. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2017, 26, 275–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.W. Motivation reconsidered: The concept of competence. Psychol. Rev. 1959, 66, 297–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R.F.; Leary, M.R. The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 117, 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlow, H.F. The nature of love. Am. Psychol. 1958, 13, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olafsen, A.H.; Halvari, H.; Forest, J.; Deci, E.L. Show them the money? The role of pay, managerial need support, and justice in a self-determination theory model of intrinsic work motivation. Scand. J. Psychol. 2015, 56, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preenen, P.T.Y.; Oeij, P.R.A.; Dhondt, S.; Kraan, K.O.; Jansen, E. Why job autonomy matters for young companies’ performance: Company maturity as a moderator between job autonomy and company performance. World Rev. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 12, 74–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trépanier, S.-G.; Forest, J.; Fernet, C.; Austin, S. On the psychological and motivational processes linking job characteristics to employee functioning: Insights from self-determination theory. Work Stress 2015, 29, 286–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Broeck, A.; Vansteenkiste, M.; De Witte, H.; Lens, W. Explaining the relationships between job characteristics, burnout, and engagement: The role of basic psychological need satisfaction. Work Stress 2008, 22, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henning, G.; Stenling, A.; Tafvelin, S.; Hansson, I.; Kivi, M.; Johansson, B.; Lindwall, M. Preretirement work motivation and subsequent retirement adjustment: A self-determination theory perspective. Work Aging Retire. 2019, 5, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, Y.; Fouquereau, E.; Fernandez, A. The relation between self-determination and retirement satisfaction among active retired individuals. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2008, 66, 329–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong-Stassen, M. Human resource practices for mature workers—And why aren’t employers using them? Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2008, 46, 334–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong-Stassen, M.; Ursel, N.D. Perceived organizational support, career satisfaction, and the retention of older workers. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2009, 82, 201–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettache, M. Les Pratiques de Gestion Des Ressources Humaines Favorisant le Maintien en Emploi et L’engagement Organisationnel Des Travailleurs Vieillissants. Ph.D Thesis, Université de Montréal, Montreal, QC, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Guérin, G.; Saba, T. Efficacité des pratiques de maintien en emploi des cadres de 50 ans et plus. Relat. Ind. Ind. Relat. 2003, 58, 590–619. [Google Scholar]

- Saba, T.; Guerin, G. Extending employment beyond retirement age: The case of health care managers in Quebec. Public Pers. Manag. 2005, 34, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veth, K.N.; Emans, B.J.M.; Van der Heijden, B.I.J.M.; Korzilius, H.P.L.M.; De Lange, A.H. Development (f)or Maintenance? An Empirical Study on the Use of and Need for HR Practices to Retain Older Workers in Health Care Organizations. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2015, 26, 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches; Sage: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kirchherr, J.; Charles, K. Enhancing the sample diversity of snowball samples: Recommendations from a research project on anti-dam movements in Southeast Asia. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0201710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Blais, M.; Martineau, S. L’analyse inductive générale: Description d’une démarche visant à donner un sens à des données brutes. Rech. Qual. 2006, 26, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, D.R. A General Inductive Approach for Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data. Am. J. Eval. 2006, 27, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Sauzend Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers; Sage Publications Ltd.: Sauzend Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong-Stassen, M.; Schlosser, F. Benefits of a supportive development climate for older workers. J. Manag. Psychol. 2008, 23, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mansour, S.; Tremblay, D.-G. What strategy of human resource management to retain older workers? Int. J. Manpow. 2019, 40, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. Health factors and early retirement among older workers. Perspect. Labour Income 2010, 22, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Remery, C.; Henkens, K.; Schippers, J.; Ekamper, P. Managing an aging workforce and a tight labor market: Views held by Dutch employers. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2003, 22, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcover, C.-M.; Topa, G. Work characteristics, motivational orientations, psychological work ability and job mobility intentions of older workers. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beier, M.E.; Torres, W.J.; Fisher, G.G.; Wallace, L.E. Age and job fit: The relationship between demands–ability fit and retirement and health. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2019, 25, 227–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burmeister, A.; Deller, J. Knowledge retention from older and retiring workers: What do we know, and where do we go from here? Work Aging Retire. 2016, 2, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ng, E.S.; Law, A. Keeping up! Older workers’ adaptation in the workplace after age 55. Can. J. Aging Rev. Can. Vieil. 2014, 33, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josten, E.; Schalk, R. The effects of demotion on older and younger employees. Pers. Rev. 2010, 39, 195–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, D.G.; Larivière, M. Les défis de fins de carrière et la retraite: Le cas du Québec. Manag. Avenir 2009, 10, 127–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templer, A.; Armstrong-Stassen, M.; Cattaneo, J. Antecedents of older workers’ motives for continuing to work. Career Dev. Int. 2010, 15, 479–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canduela, J.; Dutton, M.; Johnson, S.; Lindsay, C.; McQuaid, R.W.; Raeside, R. Ageing, skills and participation in work-related training in Britain: Assessing the position of older workers. Work Employ. Soc. 2012, 26, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Karpinska, K.; Henkens, K.; Schippers, J. Retention of older workers: Impact of managers’ age norms and stereotypes. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2013, 29, 1323–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooij, D.T.A.M.; Jansen, P.G.W.; Dikkers, J.S.E.; De Lange, A.H. The influence of age on the associations between HR practices and both affective commitment and job satisfaction: A meta-analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 2010, 31, 1111–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.K.-L.; Gardiner, E. Supporting older workers to work: A systematic review. Pers. Rev. 2019, 48, 1318–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beehr, T.A.; Bennett, M.M. Working after retirement: Features of bridge employment and research directions. Work Aging Retire. 2015, 1, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda-Chan, T.; Nakamura, J. A generativity track to life meaning in retirement: Ego-integrity returns on past academic mentoring investments. Work Aging Retire. 2016, 78, 24–37. [Google Scholar]

- Zacher, H.; Yang, J. Organizational climate for successful aging. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kunze, F.; Boehm, S.; Bruch, H. Age, resistance to change, and job performance. J. Manag. Psychol. 2013, 28, 741–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.W.; Feldman, D.C. Evaluating six common stereotypes about older workers with meta-analytical data. Pers. Psychol. 2012, 65, 821–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snape, E.; Redman, T. Too old or too young? The impact of perceived age discrimination. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2003, 13, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bal, A.C.; Reiss, A.E.; Rudolph, C.W.; Baltes, B.B. Examining positive and negative perceptions of older workers: A meta-analysis. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2011, 66, 687–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carr, E.; Hagger-Johnson, G.; Head, J.; Shelton, N.; Stafford, M.; Stansfeld, S.; Zaninotto, P. Working conditions as predictors of retirement intentions and exit from paid employment: A 10-year follow-up of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Eur. J. Ageing 2016, 13, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- St-Onge, S.; Beauchamp Legault, M.; Ballesteros-Leiva, F.; Haines, V.; Saba, T. Exploring the Black Box of Managing Total Rewards for Older Professionals in the Canadian Financial Services Sector. Can. J. Aging Rev. Can. Vieil. 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, F.; Ryan, R. The benefits of benevolence: Basic psychological needs, beneficence and the enhancement of well-being. J. Personal. 2015, 84, 750–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchet, D.; Debrand, T. Souhaiter prendre sa retraite le plus tôt possible: Santé, satisfaction au travail et facteurs monétaires. Econ. Stat. 2007, 403, 39–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, E.M.M.; Van Der Heijden, B.I.J.M.; Flynn, M. Job satisfaction, retirement attitude and intended retirement age: A conditional process analysis across workers’ level of household income. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kautonen, T.; Hytti, U.; Bögenhold, D.; Heinonen, J. Job satisfaction and retirement age intentions in Finland: Self-employed versus salary earners. Int. J. Manpow. 2012, 33, 424–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, B.D.; Dekas, K.H.; Wrzesniewski, A. On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Res. Organ. Behav. 2010, 30, 91–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.W.; Mitchell, T.R. An alternative approach: The unfolding model of voluntary employee turnover. Acad. Manag. J. 1994, 19, 51–89. [Google Scholar]

- Mobley, W.H. Intermediate linkages in the relationship between job satisfaction and employee turnover. J. Appl. Psychol. 1977, 62, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobley, W.H.; Griffeth, R.W.; Hand, H.H.; Meglino, B.M. Review and conceptual analysis of the employee turnover process. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 493–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, L.W.; Steers, R.M. Organizational, work and personal factors in employee turnover and absenteeism. Psychol. Bull. 1973, 80, 151–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolino, M.C.; Grant, A.M. The bright side of being prosocial at work, and the dark side, too: A review and agenda for research on other-oriented motives, behavior, and impact in organizations. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2016, 10, 599–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanno, K.; Sakata, K.; Ohsawa, M.; Onoda, T.; Itai, K.; Yaegashi, Y.; Tamakoshi, A. Associations of ikigai as a positive psychological factor with all-cause mortality and cause-specific mortality among middle-aged and elderly Japanese people: Findings from the Japan Collaborative Cohort Study. J. Psychosom. Res. 2009, 67, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martela, F.; Pessi, A.B. Significant work is about self-realization and broader purpose: Defining the key dimensions of meaningful work. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dudovskiy, J. The Ultimate Guide to Writing a Dissertation in Business Studies: A Step-by-Step Assistance, Business Research Methodology; Research-Methodology.net, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bal, P.M.; de Jong, S.B.; Jansen, P.G.W.; Bakker, A.B. Motivating employees to work beyond retirement: A multilevel study of the role of ideals and unit climate. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 306–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, B.A.; Autin, K.L.; Duffy, R.D. Self-determination and meaningful work: Exploring socioeconomic constraints. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posthuma, R.A.; Campion, M.A. Age stereotypes in the workplace: Common stereotypes, moderators, and future research directions. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 158–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Felps, W.; Mitchell, T.R.; Hekman, D.R.; Lee, T.W.; Holtom, B.C.; Harman, W.S. Turnover contagion: How coworkers’ job embeddedness and job search behaviors influence quitting. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 545–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grotto, A.R.; Hyland, P.K.; Caputo, A.W.; Semedo, C. Employee turnover and strategies for retention. In The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of the Psychology of Recruitment, Selection and Employee Retention; Goldstein, H.W., Pulakos, E.D., Passmore, J., Semedo, C., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 443–472. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, M. Job market signaling. In Uncertainty in Economics; Diamond, P., Rothschild, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1978; pp. 281–306. [Google Scholar]

- Cable, D.M.; Turban, D.B. The value of organizational reputation in the recruitment context: A brand-equity perspective. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 33, 2244–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blau, P. Exchange and Power in Social Life; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Hom, P.W.; Tsui, A.S.; Wu, J.B.; Lee, T.W.; Zhang, A.Y.; Fu, P.P.; Li, L. Explaining employment relationships with social exchange and job embeddedness. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotterell, N.; Eisenberger, R.; Speicher, H. Inhibiting effects of reciprocation wariness on interpersonal relationships. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1992, 62, 658–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cropanzano, R.; Mitchell, M.S. Social exchange theory: An interdisciplinary review. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 874–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Resick, C.J.; Hargis, M.B.; Shao, P.; Dust, S.B. Ethical leadership, moral equity judgments, and discretionary workplace behavior. Hum. Relat. 2013, 66, 951–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, L.; Eisenberger, R. Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 698–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant | Gender | Age | Type of Position | Number of Employees in Their Organization 1 | Number of Years in the Labor Market |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Man | 51 | Director | Over 1000 | 27 |

| 2 | Man | 58 | Director | Over 47,500 | 35 |

| 3 | Woman | 53 | Director | Over 47,500 | 30 |

| 4 | Woman | 56 | Retired | Over 47,500 | 34 |

| 5 | Woman | 53 | Director | Over 47,500 | 30 |

| 6 | Woman | 53 | Director | 2000 | 33 |

| 7 | Man | 51 | Self-employed | 44,000 | 24 |

| 8 | Man | 60 | Executive/senior professional | Over 37,000 | 37 |

| 9 | Woman | 57 | Executive/senior professional | 5000 | 35 |

| 10 | Man | 56 | In search of employment | n/a | 33 |

| 11 | Man | 60 | Executive/senior professional | 47,500 | 36 |

| 12 | Man | 53 | Executive/senior professional | Over 47,500 | 31 |

| 13 | Man | 60 | Executive/senior professional | Over 47,500 | 37 |

| 14 | Man | 65 | Retired/Consultant | n/a | 45 |

| 15 | Man | 61 | Retired/Consultant | n/a | 20 |

| 16 | Woman | 60 | Retired | 2700 | 25 |

| 17 | Man | 65 | Retired/Consultant | n/a | 39 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

St-Onge, S.; Beauchamp Legault, M.-È. What Can Motivate Me to Keep Working? Analysis of Older Finance Professionals’ Discourse Using Self-Determination Theory. Sustainability 2022, 14, 484. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010484

St-Onge S, Beauchamp Legault M-È. What Can Motivate Me to Keep Working? Analysis of Older Finance Professionals’ Discourse Using Self-Determination Theory. Sustainability. 2022; 14(1):484. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010484

Chicago/Turabian StyleSt-Onge, Sylvie, and Marie-Ève Beauchamp Legault. 2022. "What Can Motivate Me to Keep Working? Analysis of Older Finance Professionals’ Discourse Using Self-Determination Theory" Sustainability 14, no. 1: 484. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010484

APA StyleSt-Onge, S., & Beauchamp Legault, M.-È. (2022). What Can Motivate Me to Keep Working? Analysis of Older Finance Professionals’ Discourse Using Self-Determination Theory. Sustainability, 14(1), 484. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010484