The Transformation of Dorćol Power Plant: Triggering a Sustainable Urban Regeneration or Selling the Heritage?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- High quality urban design;

- Local cultural identity;

- Inclusive and participatory approach.

2. Materials and Methods

3. Case Study

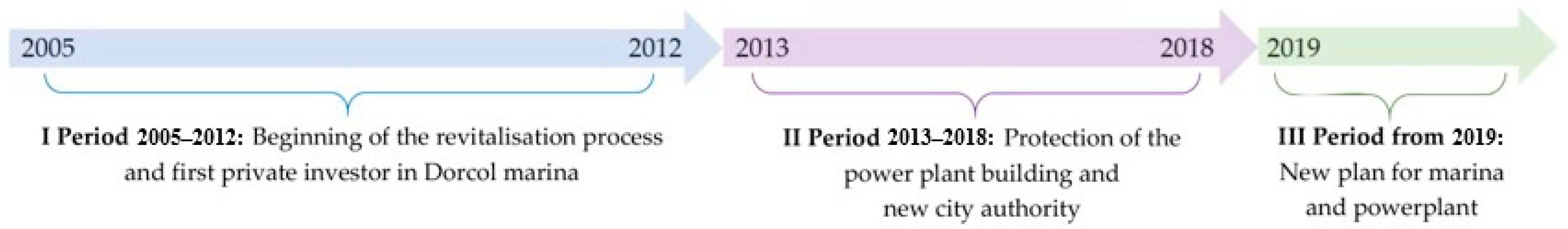

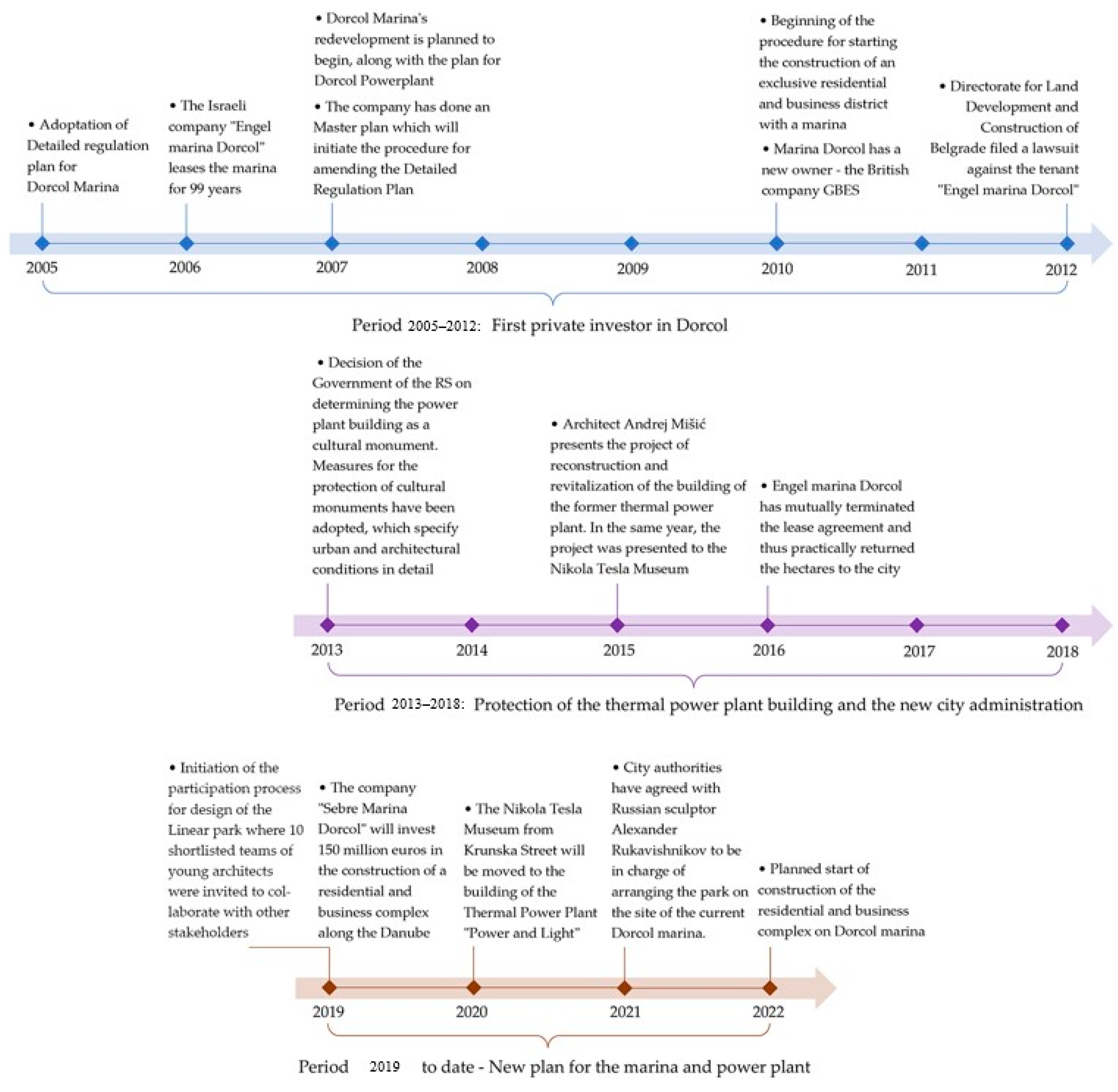

3.1. The Announcement of Private Investments (2005–2012)

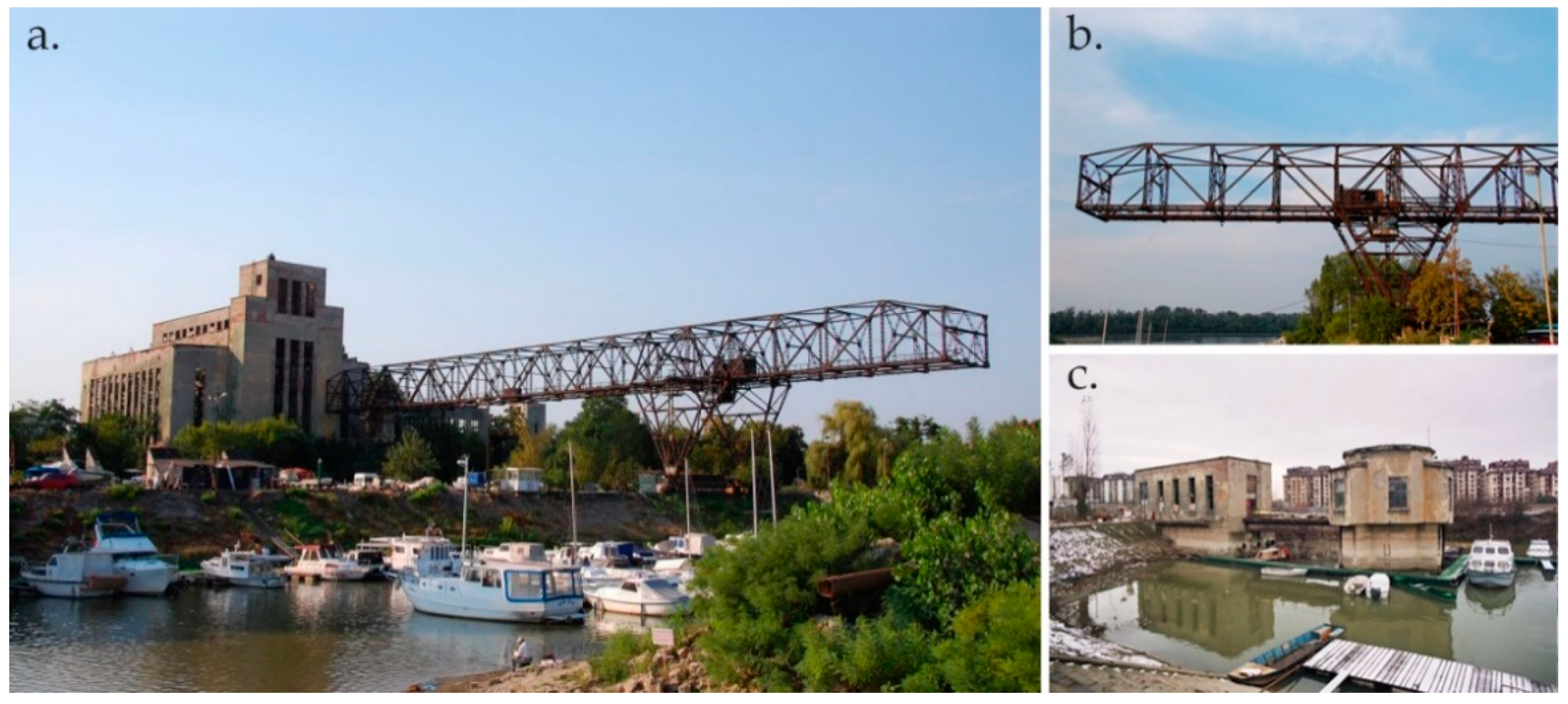

3.2. The Heritage Protection and Governmental Changes (2013–2018)

3.3. New Plans Ahead (2019–2021)

4. Results

4.1. High Quality Urban Design

4.2. Local Cultural Identity

4.3. Inclusive and Participatory Approach

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Petovar, K.; Vujošević, M. Koncept javnog interesa i javnog dobra u urbanističkom i prostornom planiranju. Sociol. Prost. Časopis Istraživanje Prost. Sociokulturnog Razvoja 2008, 46, 24–51. [Google Scholar]

- The Decision of the Government of the Republic of Serbia for Protection of Ex-Power Plant. Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia. No. 35/2013. 2013. Available online: http://www.pravno-informacioni-sistem.rs/SlGlasnikPortal/eli/rep/sgrs/vlada/odluka/2013/33/6/reg (accessed on 20 September 2021).

- Tarazona Vento, A. Mega-project meltdown: Post-politics, neoliberal urban regeneration and Valencia’s fiscal crisis. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, T. Insights in the British Debate about Urban Decline and Urban Regeneration; Working Paper; Leibniz-Institute for Regional Development and Structural Planning: Erkner, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.; Jones, P. Rethinking sustainable urban regeneration: Ambiguity, creativity, and the shared territory. Environ. Plan. A 2008, 40, 1416–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Block, T.; Paredis, E. Urban development projects catalyst for sustainable transformations: The need for entrepreneurial political leadership. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 50, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vujošević, M. Novije Promene u Teoriji i Praksi Planiranja na Zapadu i Njihove Pouke za Planiranje u Srbiji/Jugoslaviji; Institut za Arhitekturu i Urbanizam Srbije (IAUS): Beograd, Srbija, 2002; pp. 98–116. [Google Scholar]

- Peck, J.; Tickell, A. Neoliberalizing Space. Antipode 2002, 34, 380–404. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, H. The Right to the City. In Henri Lefebvre: Writings on Cities; Kofman, E., Lebas, E., Eds.; Blackwell Publishers Inc.: Malden, MA, USA, 1996; pp. 63–184. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution; Verso: London, UK, 2012; pp. 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Making Social Science Matter: Why Social Inquiry Fails and How It Can Succeed Again; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001; pp. 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Rationality and Power: Democracy in Practice; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- United Nations. New Urban Agenda: Habitat III. 2017. Available online: http://habitat3.org/wp-content/uploads/NUA-English.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Regeneration of European Sites in Cities and Urban Environments (RESCUE). Available online: https://cordis.europa.eu/article/id/83306-manual-for-sustainable-brownfield-regeneration (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Syazwani, A.K.; Jamaludin, M. Sustainable Life and Social Development through Universally Designed Environment. Asian J. Environ.-Behav. Stud. 2018, 3, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- URBACT II Capitalization. Available online: https://urbact.eu/urbact-ii-capitalisation-publications-e-book-format (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- SUR:IM (Sustainable Urban Brownfield Regeneration: Integrated Management). Available online: https://www.claire.co.uk/projects-and-initiatives/36-subr-im/105-subr-im (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Regeneration and Optimisation of Cultural Heritage in Creative and Knowledge Cities ROCK Project. Available online: https://www.heritageresearch-hub.eu/project/h2020-rock-project/ (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Glasson, J.; Wood, G. Urban regeneration and impact assessment for social sustainability. Impact Assess. Proj. Apprais. 2009, 27, 283–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.; Lee, G.K. Critical factors for improving social sustainability of urban renewal projects. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 85, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujang, N.; Zakariya, K. The Notion of Place, Place Meaning and Identity in Urban Regeneration. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 170, 709–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chavis, D.M.; Wandersman, A. Sense of community in the urban environment: A catalyst for participation and community development. Am. J. Community Psychol. 1990, 18, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.H.; Hu, T.S.; Fan, P. Social sustainability of urban regeneration led by industrial land redevelopment in Taiwan. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2019, 27, 1245–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicognani, E.; Pirini, C.; Keyes, C.; Joshanloo, M.; Rostami, R.; Nosratabadi, M. Social participation, sense of community and social well being: A study on American, Italian and Iranian university students. Soc. Indic. Res. 2008, 89, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Detailed Regulation Plan of Marina Dorcol (PDR Marina Dorćol). 2005. Available online: https://www.urbel.com/uploads/Planovi/planska-dokumentacija/4523(sl%20l%2025-05).pdf (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- The Institute for Development Planning of the City of Belgrade. Master Plan of Belgrade for 2021; The Institute for Development Planning of the City of Belgrade: Belgrade, Serbia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- The Institute for Development Planning of the City of Belgrade. The Detailed Regulation Plan of the Linear Park Belgrade (PDR Linijski Park Beograd); The Institute for Development Planning of the City of Belgrade: Belgrade, Serbia, 2021; Available online: https://www.beograd.rs/cir/gradski-oglasi-konkursi-i-tenderi/1783021-javni-uvid-u-nacrt-plana-detaljne-regulacije-za-linijski-park---stari-grad-i-palilula_2/ (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- BELgrade Urban Living LAB. Linijski Park. 2021. Available online: https://bellab.rs/linijskipark/ (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Marina “Dorcol”-(Residential Complex). (Marina “Dorćol”-(Stambeni Kompleks)). [Online Forum Post]. 12 September 2018. Available online: https://beobuild.rs/forum/viewtopic.php?t=371 (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- “Marina Dorcol” on Twice as Many Square Meters (“Marina Dorćol” Na Duplo Više Kvadrata). 13 October 2007. Available online: https://www.blic.rs/vesti/beograd/marina-dorcol-na-duplo-vise-kvadrata/gpvkrg7 (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Who Is Involved in the Resale of the Dorćol Marina (Ko je sve Umešan u Preprodaje Dorćolske Marine). 29 September 2010. Available online: https://www.politika.rs/sr/clanak/150930/Ko-je-sve-umesan-u-preprodaje-dorcolske-marine (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Weeds Instead of Marina Dorcol (Korov Umesto Marine Dorćol). 2 March 2014. Available online: https://www.novosti.rs/vesti/beograd.74.html:480818-Korov-umesto-Marine-Dorcol (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Belgrade Land Development Public Agency. Public Tender for the Location “Marina Dorcol”. (Javno Nadmetanje za Lokaciju “Marina Dorćol”). 2019. Available online: https://www.beoland.com/lat/javno-nadmetanje-za-lokaciju-marina-dorcol/ (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- For the “Marina Dorcol”-150 Million Euros (Za “Marinu Dorćol”-150 Miliona Evra). 8 April 2020. Available online: https://www.politika.rs/scc/clanak/451815/Za-Marinu-Dorcol-150-miliona-evra (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Fonet. Marina Dorcol Is Sold (Prodata Marina Dorćol). 13 September 2019. Available online: https://www.danas.rs/vesti/ekonomija/prodata-marina-dorcol-za-32-miliona-evra/ (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- “Power and Light” Is the New Home of Nikola Tesla (“Snaga I Svetlost” Novi Dom Nikole Tesle). 25 December 2020. Available online: https://www.politika.rs/sr/clanak/469539/ (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Linear Park—From A to Z (Linijski Park: Od A do Š). 23 November 2020. Available online: https://www.gradnja.rs/linijski-park-beograd/ (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Nikola Tesla Museum at the Old Headquarters in Dorcol (Muzej Nikole Tesle Na Staroj Centrali Na Dorćolu). 8 September 2018. Available online: https://www.politika.rs/scc/clanak/410771/Muzej-Nikole-Tesle-u-staroj-centrali-na-Dorcolu (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Fantastic Project for the Marina Dorcol, All in Greenery (Fantastičan Projekat Za Marinu Dorćol, Sve u Zelenilu). 19 May 2021. Available online: https://www.b92.net/biz/vesti/srbija.php?yyyy=2021&mm=05&dd=19&nav_id=1860498 (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Leary, M.E.; McCarthy, J. Emerging Reconceptualizations of Urban Regeneration. In The Routledge Companion to Urban Regeneration; Leary, M.E., McCarthy, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 117–207. [Google Scholar]

- Schwandt, T.A.; Gates, E.F.F. Case Study Methodology. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, 5th ed.; Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S., Eds.; SAGE Publishing: London, UK, 2017; pp. 600–630. [Google Scholar]

- Wansborough, M.; Mageean, A. The Role of Urban Design in Cultural Regeneration. J. Urban Des. 2000, 5, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Office of the Deputy Prime Minister ODPM. Bristol Accord: Conclusions of Ministerial Informal on Sustainable Communities in Europe; Office of the Deputy Prime Minister: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Porta, S.; Renne, L. Linking urban design to sustainability: Formal indicators of social urban sustainability field research in Perth, Western Australia. Urban Des. Int. 2005, 10, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- EU Ministers. Leipzig Charter on Sustainable European Cities; European Agency: Brussels, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Igloo Footprint TM. 2021. Available online: http://www.iglooregeneration.co.uk/footprint/ (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Colantonio, A.; Dixon, T. Urban Regeneration and Social Sustainability: Best Practice from European Cities (Real Estate Issues); Wiley-Blackwell: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, J. Integrated Urban Regeneration and Sustainability: Approaches from the European Union. In Urban Regeneration and Social Sustainability: Best Practice from European Cities (Real Estate Issues); Colantonio, A., Dixon, T., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: London, UK, 2011; pp. 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs, M. Heritage-Sustainability: Developing a Methodology for the Sustainable Appraisal of the Historic Environment. Plan. Pract. Res. 2004, 19, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agger, A. Involving citizens in sustainable development: Evidence of new forms of participation in the Danish Agenda 21 schemes. Local Environ. 2010, 15, 541–552. [Google Scholar]

- Sharifi, A.; Murayama, A. A critical review of seven selected neighborhood sustainability assessment tools. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2012, 38, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BELgrade Urban Living LAB. Partnerstvo za Urbane Inovacije. 2021. Available online: http://bellab.rs/partnerstvo/ (accessed on 24 June 2021).

- Center for Experimental and Urban Studies (Centar za Eksperimente i Urbane Studije)—CEUS. [Facebook Page]. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/ceus.rs/ (accessed on 24 June 2021).

| Key Principles | Criteria | Indicators | Author(s)/EU Agendas and Projects |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Quality Urban Design | Permeable street network | Permeability and connectivity with urban fabric | Wansborough and Mageean [43] RESCUE Project [15] ODPM [44] Porta and Renne [45] EU Ministers [46] Igloo [47] Colantonio and Dixon [48] Carpenter [49] Ujang and Zakariya [22] UN New Urban Agenda [14] |

| Well-designed and maintained non-commercial public space | Coverage of the area (%) | ||

| Acceptable density and mix of use levels | FAR Index (floor aspect ratio) | ||

| High quality urban design with diverse range of buildings and public space | Diverse types and uses of buildings and public space | ||

| Creation and integration of places with symbolic value and meaning | Spaces that have symbolic value and meaning | ||

| Promotion of greater respect of nature | Areas with nature-based design | ||

| Local Cultural Identity | Sense of place and identity | Spaces for performing arts, museums, festivals, farmers’ markets and local craft fairs, etc. | RESCUE project [15] Stubbs [50] Chan and Lee [21] Colantonio and Dixon [48] Ujang and Zakariya [22] UN Agenda 2030 [13] URBACT [17] |

| Sense of community pride | Landmark buildings, jewel parks, etc. | ||

| Protection of cultural heritage | Buildings and public spaces | ||

| Inclusive and Participatory Approach | Inclusion of diverse marginal groups in decision making, planning and design process | Presence of marginal groups in decision-making activities | RESCUE project, 2002 [15] Stubbs, 2004 [50] ODPM, 2005 [44] Colantonio and Dixon, 2011 [48] Agger, 2010 [51] Sharifi and Murayama, 2012 [52] UN Agenda 2030, 2015 [13] URBACT project, 2015 [17] Chan et al., 2019 [24] SUR:IM/ROCK project, 2019 [18,19] |

| Social mixing, inclusion and cohesion activities | Events and cultural activities encouraging interaction between people of varying ages, incomes, ethnicities and abilities | ||

| Involvement of local residents in decision making, planning and design process | Number of meetings | ||

| Network of local community associations | Number of organizations | ||

| Accessibility of public services | Number of services |

| Key Principles | Criteria/Indicator | 2005–2012 | 2013–2018 | 2019–2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Quality Urban Design | Permeable street network/Permeability and connectivity with urban fabric | Semi-permeable in the mixed-use complex; power plant connected with urban fabric | Semi-permeable in the mixed-use complex; power plant connected with urban fabric | Semi-permeable in the mixed-use complex; marina and power plant connected with urban fabric and linear park |

| Well designed and maintained non-commecial public space/Coverage of area (%) | 12% in the immediate surrounding of power plant | 12% in the immediate surrounding of power plant | 32% around the power plant and linear park | |

| Acceptable density and a mix of use levels/FAR Index (floor aspect ratio) | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | |

| High quality urban design with diverse range of buildings/Diverse types and uses of buildings and public space | no | yes/in the immediate surrounding of power plant | yes/in the immediate surrounding of power plant and linear park | |

| Creation and integration of places with symbolic value and meaning/Space with integrated symbolic value and meaning | no | yes | yes | |

| Promotion of greater respect of nature/Areas with nature-based design | no | no | yes/linear park | |

| Local Cultural Identity | Sense of place and identity/Spaces for performing arts, museums, festivals, farmers’ markets and local craft fairs, etc. | no | yes/plan for the Museum Nikola Tesla | yes/plans for Museum Nikola Tesla and multi-functional linear park |

| Sense of community pride/Landmark buildings, jewel parks, etc. | Power plant complex | Power plant complex, Museum Nikola Tesla(revitalized power plant) | Power plant complex, landmark residential complex, Museum Nikola Tesla (revitalized power plant) | |

| Protection of cultural heritage/Buildings and public spaces | General protection measures of the area by the detailed regulation plan of Marina Dorćol | Protection of the power plant complex—declaration of cultural monument | Protection of power plant complex—declaration of cultural monument | |

| Inclusive and Participatory Approach | Inclusion of diverse marginal groups in, decision making process/Presence of marginal groups in decision-making activities | no | no | yes/inclusion of some organizations in the design process of linear park |

| Social mixing, inclusion and participatory activities/Events and cultural activities encouraging interaction between people of varying ages, incomes, ethnicities and abilities | no | no | yes/design workshops and discussion panels | |

| Involvement of local residents in decision making process/Number of meetings | 0 | 0 | >10 | |

| Network of local community associations/Number of organizations | 0 | 0 | >5 | |

| Accessibility of public services/Number of services | 0 | 0 | 2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Simic, I.; Stupar, A.; Grujicic, A.; Mihajlov, V.; Cvetkovic, M. The Transformation of Dorćol Power Plant: Triggering a Sustainable Urban Regeneration or Selling the Heritage? Sustainability 2022, 14, 523. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010523

Simic I, Stupar A, Grujicic A, Mihajlov V, Cvetkovic M. The Transformation of Dorćol Power Plant: Triggering a Sustainable Urban Regeneration or Selling the Heritage? Sustainability. 2022; 14(1):523. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010523

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimic, Ivan, Aleksandra Stupar, Aleksandar Grujicic, Vladimir Mihajlov, and Marija Cvetkovic. 2022. "The Transformation of Dorćol Power Plant: Triggering a Sustainable Urban Regeneration or Selling the Heritage?" Sustainability 14, no. 1: 523. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010523

APA StyleSimic, I., Stupar, A., Grujicic, A., Mihajlov, V., & Cvetkovic, M. (2022). The Transformation of Dorćol Power Plant: Triggering a Sustainable Urban Regeneration or Selling the Heritage? Sustainability, 14(1), 523. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010523