Examining Leadership Capabilities, Risk Management Practices, and Organizational Resilience: The Case of State-Owned Enterprises in Indonesia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Resilience and Dynamic Capabilities

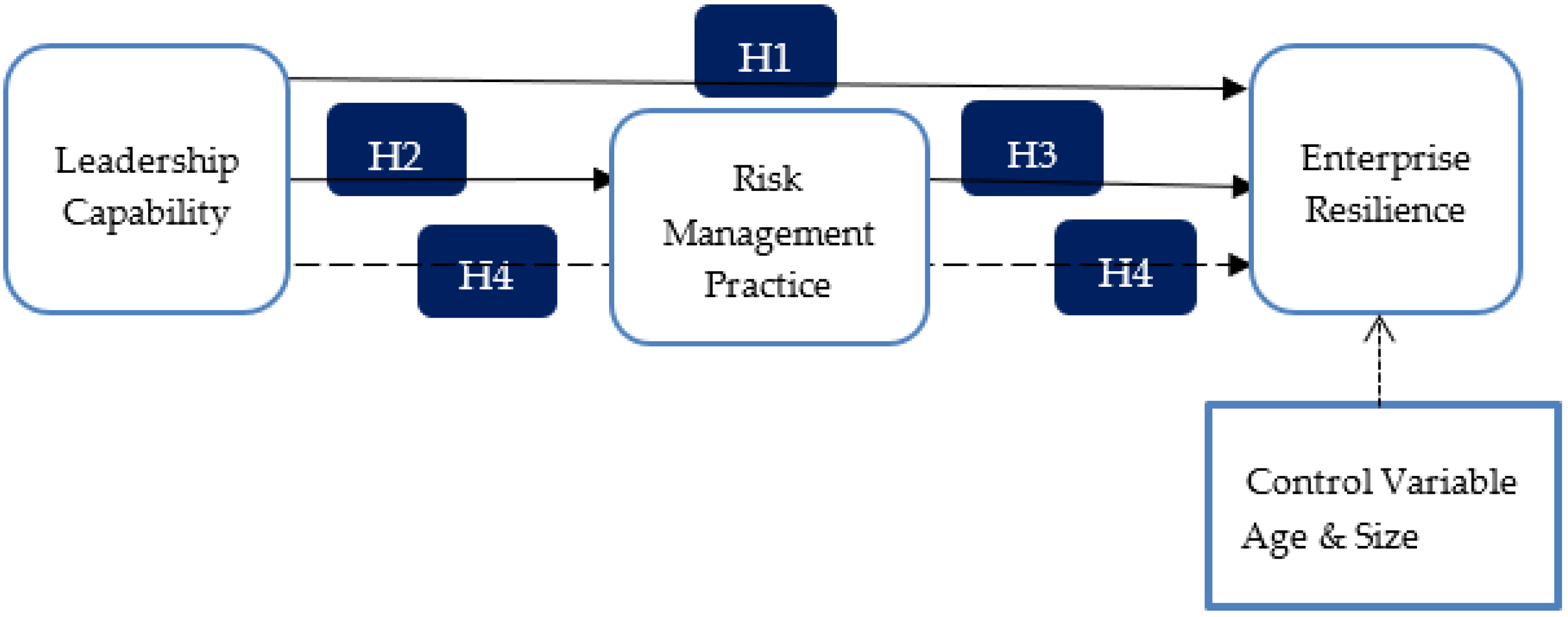

2.2. Leadership Capabilities and Enterprise Resilience

2.3. Leadership Capability and Risk Management

2.4. Risk Management Practice and Enterprise Resilience

2.5. The Mediating Effect of Risk Management Practice on the Relationship between Leadership Capabilities and Enterprise Resilience

3. Methodology

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Path Coefficient

4.3. The Measurement Model Assessment

4.4. The Structural Model Assessment

4.5. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morales, S.N.; Martínez, L.R.; Gómez, J.A.H.; López, R.R.; Torres-Argüelles, V. Predictors of organizational resilience by factorial analysis. Int. J. Eng. Bus. Manag. 2019, 11, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annarelli, A.; Nonino, F. Strategic and operational management of organizational resilience: Current state of research and future directions. Omega 2016, 62, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoemaker, P.J.H.; Heaton, S.; Teece, D. Innovation, dynamic capabilities, and leadership. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2018, 61, 15–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teixeira, E.O.; Werther, W.B. Resilience: Continuous renewal of competitive advantages. Bus. Horiz. 2013, 56, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudakova, M.; Lahuta, P. Risk Management as a Tool for Building a Resilient Enterprise. In Proceedings of the 52nd International Scientific Conference on Economic and Social Development, Porto, Portugal, 16–17 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sin, I.S.M.; Ng, K.Y.N. The Evolving Building Blocks of Enterprise Resilience: Ensnaring the Interplays to take the Helm. J. Appl. Bus. Manag. Stud. 2013, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cheese, P. Managing risk and building resilient organisations in a riskier world. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2016, 3, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, A. Why Uncertainty Means Just One Thing to Entrepreneurs: Opportunity. Forbes. 2017. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/alisoncoleman/2017/01/05/why-uncertainty-means-just-one-thing-to-entrepreneurs-opportunity/#3ac54ab51115 (accessed on 18 May 2019).

- Fiksel, J.; Polyviou, M.; Croxton, K.L.; Pettit, T.J. From Risk to Resilience: Learning to Deal with Disruption. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2015, 56, 79–86. Available online: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/from-risk-to-resilience-learning-to-deal-with-disruption/ (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Teece, D.J.; Peteraf, M.; Leih, S. Dynamic capabilities and organizational agility: Risk, uncertainty, and strategy in the innovation economy. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2016, 58, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ishak, A.W.; Williams, E.A. A dynamic model of organizational resilience: Adaptive and anchored approaches. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2018, 23, 180–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. The COVID-19 Crisis and State Ownership in the Economy: Issues and Policy Considerations. 2020. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/772fc3df-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/772fc3df-en (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Büge, M.; Egeland, M.; Kowalski, P.; Sztajerowska, M. State-Owned Enterprises in the Global Economy: Reason for Concern? Vox. 2013. Available online: http://www.voxeu.org/article/state-owned-enterprises-global-economy-reason-concern (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- International Monetary Fund, Fiscal Affairs Dept. State-Owned Enterprises: The Other Government. In Fiscal Monitor; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; ISBN 9781513537511. [Google Scholar]

- PwC’s Public Sector Research Centre State-Owned Enterprises Catalysts for Public Value Creation? 2015. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/gr/en/publications/assets/state-owned-enterprises-catalysts-for-public-value-creation.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Heo, K. Effects of Corporate Governance on the Performance of State-Owned Enterprises; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/523421534424982014/Effects-of-corporate-governance-on-the-performance-of-state-owned-enterprise (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Koch, S. The Secret to Successful State-Owned Enterprises is How They Are Run. The Conversation. 2016. Available online: https://theconversation.com/the-secret-to-successful-state-owned-enterprises-is-how-theyre-run-53118 (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Khatri, Y.; Ikhsan, M. Enhancing the Development Contribution of Indonesia’s State-Owned Enterprises. In Reforms, Opportunities, and Challenges for State-Owned Enterprises; Ginting, E., Naqvi, K., Eds.; Asian Development Bank: Mandaluyong, Philippines, 2020; pp. 84–132. ISBN 978-92-9262-283-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of State-Owned Enterprises—Republic of Indonesia BUMN Untuk Indonesia. Ministry of State-Owned Enterprise Republic of Indonesia. 2020. Available online: https://bumn.go.id/responsible/program/bumn-untuk-indonesia-sn (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- International Finance Corporation and World Bank Group. State-Owned Enterprise. 2018. Available online: https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/topics_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/ifc+cg/topics/state-owned+enterprises (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Ministry of Finance—Republic of Indonesia Pemerintah Jaga Keberlangsungan BUMN dalam Masa Pandemi COVID. 2020. Available online: https://www.kemenkeu.go.id/publikasi/berita/pemerintah-jaga-keberlangsungan-bumn-dalam-masa-pandemi-covid-19-dengan-4-modalitas/ (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Coutu, D.L. How resilience works. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Hamel, G.; Välikangas, L. The quest for resilience. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2003, 81, 52–63, 131. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12964393 (accessed on 13 April 2022). [PubMed]

- McManus, S.; Seville, E.; Vargo, J.; Brunsdon, D. Facilitated Process for Improving Organizational Resilience. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2008, 9, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chowdhury, M.; Prayag, G.; Orchiston, C.; Spector, S. Postdisaster Social Capital, Adaptive Resilience and Business Performance of Tourism Organizations in Christchurch, New Zealand. J. Travel Res. 2018, 58, 1209–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkov, I.; Trump, B.D. Risk, Systems and Decisions: The Science and Practice of Resilience; Linkov, I., Keisler, J., Lambert, J.H., Figueira, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; ISBN 978-3-030-04565-4. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, J.A. Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C.E.; Finkelstein, S.; Mitchell, W.; Peteraf, M.A.; Singh, H.; Teece, D.J.; Winter, S.G. Dynamic capabilities and organizational process. In Dynamic Capabilities: Understanding Strategic Change in Organization; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007; ISBN 9781405159043. [Google Scholar]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jiang, Y.; Ritchie, B.W.; Verreynne, M.L. Building tourism organizational resilience to crises and disasters: A dynamic capabilities view. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2019, 21, 882–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.V.; Vargo, J.; Seville, E. Developing a Tool to Measure and Compare Organizations’ Resilience. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2013, 14, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.Z.A.; Waqas, F.; Haroon, R. Organizational Resilience and Complex Systems. J. Manag. Res. 2019, 6, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kevill, A.; Trehan, K.; Easterby-Smith, M. Leadership Development as a Micro-foundation of Dynamic Capability: A Critical Consideration. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference in Critical Management Studies, Manchester, UK, 10–12 July 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bhamra, R.; Dani, S.; Burnard, K. Resilience: The concept, a literature review and future directions. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011, 49, 5375–5393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponis, S.T.; Koronis, E. Supply Chain Resilience: Definition of Concept and Its Formative Elements. J. Appl. Bus. Res. 2012, 28, 921–930. Available online: https://clutejournals.com/index.php/JABR/article/view/7234 (accessed on 13 April 2022). [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Dynamic Capabilities: Routines versus Entrepreneurial Action. J. Manag. Stud. 2012, 49, 1395–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogodistov, Y.; Wohlgemuth, V. Enterprise risk management: A capability-based perspective. J. Risk Financ. 2017, 18, 234–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giniuniene, J.; Jurksiene, L. Dynamic Capabilities, Innovation and Organizational Learning: Interrelations and Impact on Firm Performance. In Proceedings of the 20th International Scientific Conference Economics and Management—2015 (ICEM-2015), Kaunas, Lithuania, 6–8 May 2015; Volume 213, pp. 985–991. [Google Scholar]

- Bracci, E.; Tallaki, M. Resilience capacities and management control systems in public sector organisations. J. Account. Organ. Chang. 2021, 17, 332–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slagmulder, R.; Devoldere, B. Transforming under deep uncertainty: A strategic perspective on risk management. Bus. Horiz. 2018, 61, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McColl-Kennedy, J.R.; Anderson, R.D. Impact of leadership style and emotions on subordinate performance. Leadersh. Q. 2002, 13, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.M.; Cornelius, C.J.; Colvin, K. Visionary leadership and its relationship to organizational effectiveness. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2014, 35, 566–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wart, M.; Roman, A.; Wang, X.H.; Liu, C. Operationalizing the definition of e-leadership: Identifying the elements of e-leadership. Int. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2016, 85, 80–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, T.; Cäker, M.; Tengblad, S.; Wickelgren, M. Building traits for organizational resilience through balancing organizational structures. Scand. J. Manag. 2019, 35, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalziell, E.P.; McManus, S.T. Resilience, Vulnerability, and Adaptive Capacity: Implications for System Performance. In Proceedings of the 1st International Forum for Engineering Decision Making (IFED), Stoos, Switzerland, 5–8 December 2004; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Sutcliffe, K.M.; Vogus, T.J. Organizing for Resilience. In Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundation of a New Discipline; Cameron, K.S., Dutton, J.E., Quinn, R.E., Eds.; Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc: Oakland, CA, USA, 2003; pp. 94–110. Available online: http://www.bus.umich.edu/Positive/PDF/Dutton-POS-Encyc-of-Career-Devel.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Lengnick-Hall, C.A.; Beck, T.E. Adaptive fit versus robust transformation: How organizations respond to environmental change. J. Manag. 2005, 31, 738–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Dynamic capabilities as (workable) management systems theory. J. Manag. Organ. 2018, 24, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ambrosini, V.; Bowman, C.; Collier, N. Dynamic capabilities: An exploration of how firms renew their resource base. Br. J. Manag. 2009, 20, S9–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ledesma, J. Conceptual frameworks and research models on resilience in leadership. SAGE Open 2014, 4, 2158244014545464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, P.; Rossieta, H. Top management team (TMT) characteristics and profitability: The case of the conflicting objectives of Indonesian SOEs. Pertanika J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2019, 27, 113–129. [Google Scholar]

- Lengnick-Hall, C.A.; Beck, T.E.; Lengnick-Hall, M.L. Developing a capacity for organizational resilience through strategic human resource management. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2011, 21, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erol, O.; Sauser, B.J.; Mansouri, M. A framework for investigation into extended enterprise resilience. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2010, 4, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, G.C.; Dionne, S.D.; Sayama, H.; Schmid, M. Leadership in the Digital Era: Social Media, Big Data, Virtual Reality, Computational Methods, and Deep Learning. Leadersh. Q. 2019, 30, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, N.; Park, S. Supply chain leadership driven strategic resilience capabilities management: A leader-member exchange perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dartey-Baah, K. Resilient leadership: A transformational-transactional leadership mix. J. Glob. Responsib. 2015, 6, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borgelt, K.; Falk, I. The leadership/management conundrum: Innovation or risk management? Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2007, 28, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharin, S.N.; Yusof, F.; Said, J.; Zahari, A.I. Assessing Organizational Resilience of Private Higher Learning Institutions. Malays. Online J. Manag. 2021, 9, 53–72. Available online: http://journal.kuis.edu.my/attarbawiy/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/1-16.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Suryaningtyas, D.; Sudiro, A.; Eka, A.T.; Dodi, W.I. Organizational resilience and organizational performance: Examining the mediating roles of resilient leadership and organizational culture. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2019, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Ree, E.; Ellis, L.A.; Wiig, S. Managers’ role in supporting resilience in healthcare: A proposed model of how managers contribute to a healthcare system’s overall resilience. Int. J. Health Gov. 2021, 26, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehir, C.; Narcıkara, E. Effects of Resilience on Productivity under Authentic Leadership. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 235, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwick, F.S.; Martini, B.L.; Charney, D.S.; Southwick, S.M. Leadership and Resilience. In Leadership Today, Springer Texts in Business and Economics; Marques, J., Dhiman, S., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 315–333. ISBN 9783319310367. [Google Scholar]

- Boin, A.; Kuipers, S.; Overdijk, W. Leadership in times of crisis: A framework for assessment. Int. Rev. Public Adm. 2013, 18, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kane, G.C.; Nanda, R.; Phillips, A.N.; Copulsky, J. Leading through the Fog of Disruption: The Strength of Purpose, Values, and Mission. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/topics/leadership/enterprise-resilience-leading-through-disruption.html (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Leslie, K.; Canwell, A. Leadership at all levels: Leading public sector organisations in an age of austerity. Eur. Manag. J. 2010, 28, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd Aziz, M.A.; Rahman, H.A.; Alam, M.M.; Said, J. Enhancement of the Accountability of Public Sectors through Integrity System, Internal Control System and Leadership Practices: A Review Study. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 28, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alam, M.M.; Johari, R.J.; Said, J. An empirical assessment of employee integrity in the public sector of Malaysia. Int. J. Ethics Syst. 2018, 34, 458–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, S.; Bryce, C.; Ring, P. Risk and the Strategic Role of Leadership. 2018. Available online: www.accaglobal.com (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Fernández-Muñiz, B.; Montes-Peón, J.M.; Vázquez-Ordás, C.J. Safety leadership, risk management and safety performance in Spanish firms. Saf. Sci. 2014, 70, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boin, A.; Hart, P. Public Leadership in Times of Crisis: Mission Impossible? Public Adm. Rev. 2003, 63, 544–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing-gui, C.; Kai, L.; Ye-jiao, L.; Qi-hua, S.; Jian, Z. Risk management and workers’ safety behavior control in coal mine. Saf. Sci. 2012, 50, 909–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebenberg, A.P.; Hoyt, R.E. The Determinants of Enterprise Risk Management: Evidence From the Appointment of Chief Risk Officers. Risk Manag. Insur. Rev. 2003, 6, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, S.; Sodhi, M.M.S. Managing risk to avoid: Supply-chain breakdown. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2004, 46, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Nauck, F.; Pancaldi, L.; Poppensieker, T.; White, O. The Resilience Imperative: Succeeding in Uncertain Times. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/risk-and-resilience/our-insights/the-resilience-imperative-succeeding-in-uncertain-times (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Marsh Building Stronger Manufacturing and Automotive Companies: A Resilience Planning Guide. 2021. Available online: https://www.marsh.com/us/industries/manufacturing-automotive/manu-auto-enterprise-risk-resiliency-strategies.html (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Parker, H.; Ameen, K. The role of resilience capabilities in shaping how firms respond to disruptions. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 88, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwak, D.-W.; Seo, Y.-J.; Mason, R. Investigating the relationship between supply chain innovation, risk management capabilities and competitive advantage in global supply chains. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2018, 38, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louisot, J.-P. Risk and/or Resilience Management. Risk Gov. Control Financ. Mark. Inst. 2015, 5, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkov, I.; Bridges, T.; Creutzig, F.; Decker, J.; Fox-Lent, C.; Kröger, W.; Lambert, J.H.; Levermann, A.; Montreuil, B.; Nathwani, J.; et al. Changing the resilience paradigm. Nat. Clim. Change 2014, 4, 407–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.; Rustambekov, E.; Mcshane, M.; Fainshmidt, S. Enterprise Risk Management as a Dynamic Capability: A test of its effectiveness during a crisis. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2014, 35, 555–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, M.M.; Rabechini, R., Jr. Impact of risk management on project performance: The importance of soft skills. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 321–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Abrrow, H.; Alnoor, A.; Abbas, S. The Effect of Organizational Resilience and CEO’s Narcissism on Project Success: Organizational Risk as Mediating Variable. Organ. Manag. J. 2018, 16, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambulkar, S.; Blackhurst, J.; Grawe, S. Firm’s resilience to supply chain disruptions: Scale development and empirical examination. J. Oper. Manag. 2015, 33–34, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, J.M.; Klein, R.; Miller, J.; Sridharan, V. How internal integration, information sharing, and training affect supply chain risk management capabilities. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2016, 46, 953–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durach, C.F.; Wieland, A.; Machuca, J.A. Antecedents and dimensions of supply chain robustness: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2015, 45, 118–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kantur, D.; Iseri-Say, A. Measuring Organizational Resilience: A Scale Development. J. Bus. Econ. Financ. 2015, 4, 456–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ericksen, E.P. A regression method for estimating population changes of local areas. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1974, 69, 867–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, A.H.A.; El-Demerdash, S.M. The Relationship between Professional Values and Clinical Decision Making among Nursing Student. IOSR J. Nurs. Health Sci. 2017, 6, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.S.; Zhou, A.J.; Feng, J.; Jiang, S. Dynamic capabilities and organizational performance: The mediating role of innovation. J. Manag. Organ. 2019, 25, 731–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Erol, O.; Henry, D.; Sauser, B.; Mansouri, M. Perspectives on measuring enterprise resilience. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Systems Conference Proceedings, SysCon 2010, San Diego, CA, USA, 5–8 April 2010; pp. 587–592. [Google Scholar]

- McManus, S. Organisational Resilience in New Zealand, University of Canterbury. 2008. Available online: https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/handle/10092/1574 (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Stephenson, A.; Seville, E.; Vargo, J.; Roger, D. Benchmark Resilience: A Study of the Resilience of Organisations in the Auckland Region; Resilient Organisations: Christchurch, New Zealand, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson, A.; Vargo, J.; Seville, E. Measuring and comparing organisational resilience in Auckland. Aust. J. Emerg. Manag. 2010, 25, 27–32. [Google Scholar]

- Maruhun, E.N.S.; Atan, R.; Yusuf, S.N.S.; Said, J. Developing Enterprise Risk Management Index for Shariah Compliant Companies. Glob. J. Al Thaqafah 2018, 8, 189–205. [Google Scholar]

- Goh, S.; Richards, G. Benchmarking the Learning Capability of Organizations. Eur. Manag. J. 1997, 15, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivipõld, K.; Vadi, M. A Tool for Measuring Institutional Leadership and Its Implementation for the Evaluation of Organizational Leadership Capability. 2008. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:ttu:wpaper:172 (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Kivipõld, K.; Vadi, M.; Kivipold, K.; Vadi, M.; Kivipõld, K.; Vadi, M. A measurement tool for the evaluation of organizational leadership capability. Balt. J. Manag. 2010, 5, 118–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youndt, M.A.; Snell, S.A.; Dean, J.W.; Lepak, D.P. Human resource management, manufacturing strategy, and firm performance. Acad. Manag. J. 1996, 39, 836–866. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, J.R.; Mathur, A. The value of online surveys. Internet Res. 2005, 15, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, F.G.S.; Schiele, H.; Hüttinger, L. Supplier satisfaction: Explanation and out-of-sample prediction. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 4613–4623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Podsakoff, N.P. Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2012, 63, 539–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G.S. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 546–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. Int. J. e-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- O’Sullivan, D.; Abela, A.V. Marketing performance measurement ability and firm performance. J. Mark. 2007, 71, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, G.; Lampert, C.M. Entrepreneurship in the large corporation: A longitudinal study of how established firms create breakthrough inventions. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 521–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, T. Firm growth, size, age and behavior in Japanese manufacturing. Small Bus. Econ. 2005, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, J.; Liu, Y.; Hall, A.; Ketchen, D. How much do high-performance work practices matter? A meta-analysis of their effects on organizational performance. Pers. Psychol. 2006, 59, 501–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C.E.; Peteraf, M.A. The dynamic resource-based view: Capability lifecycles. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Huang, Q.; Wei, S.; Huang, L. The impacts of IT capability on internet-enabled supply and demand process integration, and firm performance in manufacturing and services. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2015, 26, 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2018, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J., Jr.; Hult, G.T.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd ed.; Sage Publication Asia-Pacific Pte. Ltd.: Singapore, 2017; ISBN 9781483377445. Available online: http://study.sagepub.com/hairprimer2e (accessed on 13 April 2022).

- Ramayah, T.; Cheah, J.; Chuah, F.; Ting, H.; Memon, M.A. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using SmartPLS 3.0: An Updated and Practical Guide to Statistical Analysis; Pearson Malaysia Sdn Bhd: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Siguaw, J.A. Formative versus reflective indicators in organizational measure development: A comparison and empirical illustration. Br. J. Manag. 2006, 17, 263–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gold, A.H.; Malhotra, A.; Segars, A.H. Knowledge management: An organizational capabilities perspective. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2001, 18, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: New York, NY, USA, 1988; ISBN 0-8058-0283-5. [Google Scholar]

- Shmueli, G.; Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Cheah, J.H.; Ting, H.; Vaithilingam, S.; Ringle, C.M. Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLSpredict. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 2322–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, N.; Park, S. Evidence-based resilience management for supply chain sustainability: An interpretive structural modelling approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Teece, D.J. Dynamic capabilities and entrepreneurial management in large organizations: Toward a theory of the (entrepreneurial) firm. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2016, 86, 202–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahari, A.I.; Mohamed, N.; Said, J.; Yusof, F. Assessing the mediating effect of leadership capabilities on the relationship between organisational resilience and organisational performance. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2022, 49, 280–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Constructs | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistic | Std. Error | Statistic | Std. Error | |||

| RMP | 5.855 | 0.752 | −0.676 | 0.136 | 0.423 | 0.271 |

| LC | 6.336 | 0.570 | −0.757 | 0.136 | 0.194 | 0.271 |

| ER | 5.510 | 0.780 | −0.670 | 0.136 | 0.854 | 0.271 |

| Variables | Categories | Frequency (n: 322) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ENTERPRISE PROFILE | |||

| Enterprise age | 1–10 years | 73 | 22.67 |

| More than 10–20 years | 47 | 14.60 | |

| More than 20–30 years | 46 | 14.29 | |

| More than 30–40 years | 24 | 7.45 | |

| More than 40–50 years | 44 | 13.66 | |

| More than 50 years | 88 | 27.33 | |

| Number of Employees | Less than and equal to 500 | 157 | 48.76 |

| 501–1000 | 39 | 12.11 | |

| 1001–10,000 | 99 | 30.75 | |

| More than 10,000 | 27 | 8.39 | |

| Type of SOEs | SOEs—Persero Listed | 31 | 9.63 |

| SOEs—Persero | 94 | 29.19 | |

| SOEs—Perum | 7 | 2.17 | |

| Subsidiary of SOEs | 190 | 59.01 | |

| Core Business | Agriculture, forestry, and fishery | 27 | 8.39 |

| Mining and excavation | 13 | 4.04 | |

| Processing industry | 50 | 15.53 | |

| Electricity and gas supply | 13 | 4.04 | |

| Water and waste management | 3 | 0.93 | |

| Construction | 42 | 13.04 | |

| Trade and retail | 14 | 4.35 | |

| Transportation and warehousing | 61 | 18.94 | |

| Provision of accommodation | 4 | 1.24 | |

| Information and communication | 10 | 3.11 | |

| Financial and insurance | 54 | 16.77 | |

| Real Estate | 20 | 6.21 | |

| Professional scientific and technical services | 11 | 3.42 | |

| Average revenue in the last 3 years (in Billion IDR) | Less than and equal to 1000 | 154 | 47.83 |

| 1001–10,000 | 114 | 35.40 | |

| More than 10,000 | 54 | 16.77 | |

| INFORMANT PROFILE | |||

| Gender | Male | 274 | 85.09 |

| Female | 48 | 14.91 | |

| Age | Below 30 years | 4 | 1.24 |

| 30–40 years | 41 | 12.73 | |

| 41–50 years | 120 | 37.27 | |

| Above 50 years | 157 | 48.76 | |

| Position | CEO | 99 | 30.75 |

| Finance & Risk Director | 59 | 18.32 | |

| Others Director | 56 | 17.39 | |

| Senior Manager | 108 | 33.54 | |

| Education | Doctor/PhD | 12 | 3.73 |

| Master | 173 | 53.73 | |

| Degree/Bachelor | 134 | 41.61 | |

| Diploma 3 or below | 3 | 0.93 | |

| Length of Service in Current SOEs | Less than one year | 46 | 14.29 |

| 1–5 years | 135 | 41.93 | |

| 5–10 years | 33 | 10.25 | |

| More than ten years | 108 | 33.54 | |

| Length of Service in Previous SOEs | 0 year (Never) | 129 | 40.06 |

| Less than one year | 3 | 0.93 | |

| 1–5 years | 27 | 8.39 | |

| 5–10 years | 22 | 6.83 | |

| More than ten years | 141 | 43.79 | |

| Length of Service in non-SOEs | 0 year (Never) | 140 | 43.48 |

| Less than one year | 35 | 10.87 | |

| 1–5 years | 75 | 23.29 | |

| 5–10 years | 22 | 6.83 | |

| More than ten years | 50 | 15.53 | |

| Background | Professional | 250 | 77.64 |

| Politician | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Bureaucrat | 10 | 3.11 | |

| Academician | 24 | 7.45 | |

| Others | 38 | 11.80 |

| Internal Consistency | Convergent Validity | Model Fit | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability | AVE | SRMR | |

| LC | 0.941 | 0.949 | 0.630 | 0.065 |

| ER | 0.940 | 0.948 | 0.567 | |

| RMP | 0.942 | 0.950 | 0.635 | |

| CV Age | CV Rev | ER | LC | RMP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV Age | |||||

| CV Rev | 0.199 | ||||

| ER | 0.051 | 0.039 | |||

| LC | 0.076 | 0.063 | 0.689 | ||

| RMP | 0.141 | 0.066 | 0.741 | 0.716 |

| R2 | f2 | Q2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ER | 0.572 | 0.315 | |

| RMP | 0.458 | 0.287 | |

| LC 🡢 RMP | 0.845 | ||

| RMP 🡢 ER | 0.281 | ||

| LC 🡢 ER | 0.158 |

| Direct Effects | β | SD | t-Value | p-Value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1: LC 🡢 ER | 0.354 | 0.059 | 6012 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H2: LC 🡢 RMP | 0.677 | 0.037 | 18,489 | 0.000 | Supported |

| H3: RMP 🡢 ER | 0.475 | 0.053 | 8915 | 0.000 | Supported |

| Mediating Effects | Beta | S.E. | t-value | p-value | Decision |

| H4: LC 🡢 RMP 🡢 ER | 0.322 | 0.048 | 6759 | 0.000 | Supported |

| (PLS) | RMSE | MAE | MAPE | Q²_ Predict | (LM) | RMSE | MAE | MAPE | Q²_ Predict |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER1 | 0.703 | 0.552 | 10,770 | 0.396 | ER1 | 0.729 | 0.575 | 11,251 | 0.351 |

| ER2 | 0.708 | 0.559 | 10,728 | 0.384 | ER2 | 0.696 | 0.573 | 10,815 | 0.404 |

| ER3 | 0.752 | 0.597 | 11,743 | 0.362 | ER3 | 0.758 | 0.606 | 11,818 | 0.352 |

| ER4 | 0.841 | 0.652 | 13,574 | 0.299 | ER4 | 0.859 | 0.671 | 13,890 | 0.268 |

| ER5 | 0.917 | 0.701 | 16,082 | 0.253 | ER5 | 0.963 | 0.720 | 16,672 | 0.177 |

| ER6 | 0.810 | 0.625 | 14,018 | 0.396 | ER6 | 0.812 | 0.634 | 14,051 | 0.394 |

| ER7 | 1.075 | 0.791 | 19,066 | 0.176 | ER7 | 1.105 | 0.809 | 19,502 | 0.128 |

| ER8 | 0.879 | 0.679 | 14,978 | 0.280 | ER8 | 0.899 | 0.699 | 15,437 | 0.248 |

| ER9 | 0.857 | 0.649 | 14,666 | 0.319 | ER9 | 0.879 | 0.672 | 15,088 | 0.283 |

| ER10 | 1.197 | 0.957 | 25,188 | 0.088 | ER10 | 1.211 | 0.970 | 25,212 | 0.065 |

| ER11 | 1.215 | 0.968 | 27,303 | 0.069 | ER11 | 1.217 | 0.973 | 27,266 | 0.067 |

| ER12 | 1.124 | 0.879 | 22,355 | 0.083 | ER12 | 1.134 | 0.892 | 22,560 | 0.066 |

| ER13 | 1.065 | 0.822 | 20,378 | 0.170 | ER13 | 1.063 | 0.834 | 20,376 | 0.173 |

| ER14 | 1.101 | 0.882 | 23,008 | 0.098 | ER14 | 1.100 | 0.886 | 22,972 | 0.098 |

| RMP1 | 0.728 | 0.509 | 9803 | 0.279 | RMP1 | 0.757 | 0.527 | 10,086 | 0.221 |

| RMP2 | 0.691 | 0.522 | 9442 | 0.283 | RMP2 | 0.713 | 0.536 | 9714 | 0.238 |

| RMP3 | 0.742 | 0.582 | 10,892 | 0.325 | RMP3 | 0.771 | 0.594 | 11,143 | 0.271 |

| RMP4 | 0.757 | 0.596 | 11,141 | 0.294 | RMP4 | 0.774 | 0.612 | 11,427 | 0.261 |

| RMP5 | 0.766 | 0.607 | 11,503 | 0.278 | RMP5 | 0.789 | 0.616 | 11,696 | 0.233 |

| RMP6 | 0.757 | 0.604 | 11,429 | 0.342 | RMP6 | 0.770 | 0.604 | 11,416 | 0.319 |

| RMP7 | 1.007 | 0.776 | 16,440 | 0.198 | RMP7 | 1.030 | 0.793 | 16,829 | 0.161 |

| RMP8 | 0.917 | 0.719 | 15,409 | 0.306 | RMP8 | 0.937 | 0.729 | 15,644 | 0.277 |

| RMP9 | 1.066 | 0.828 | 19,657 | 0.230 | RMP9 | 1.060 | 0.816 | 19,482 | 0.238 |

| RMP10 | 0.809 | 0.616 | 12,089 | 0.286 | RMP10 | 0.814 | 0.626 | 12,180 | 0.277 |

| RMP11 | 0.728 | 0.554 | 10,521 | 0.312 | RMP11 | 0.731 | 0.552 | 10,393 | 0.307 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lisdiono, P.; Said, J.; Yusoff, H.; Hermawan, A.A. Examining Leadership Capabilities, Risk Management Practices, and Organizational Resilience: The Case of State-Owned Enterprises in Indonesia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6268. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106268

Lisdiono P, Said J, Yusoff H, Hermawan AA. Examining Leadership Capabilities, Risk Management Practices, and Organizational Resilience: The Case of State-Owned Enterprises in Indonesia. Sustainability. 2022; 14(10):6268. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106268

Chicago/Turabian StyleLisdiono, Purwatiningsih, Jamaliah Said, Haslinda Yusoff, and Ancella Anitawati Hermawan. 2022. "Examining Leadership Capabilities, Risk Management Practices, and Organizational Resilience: The Case of State-Owned Enterprises in Indonesia" Sustainability 14, no. 10: 6268. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106268