Sustainability Perspectives of the Sharing Economy: Process of Creating a Library of Things in Finland

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Process of Creating an LoT in Finland

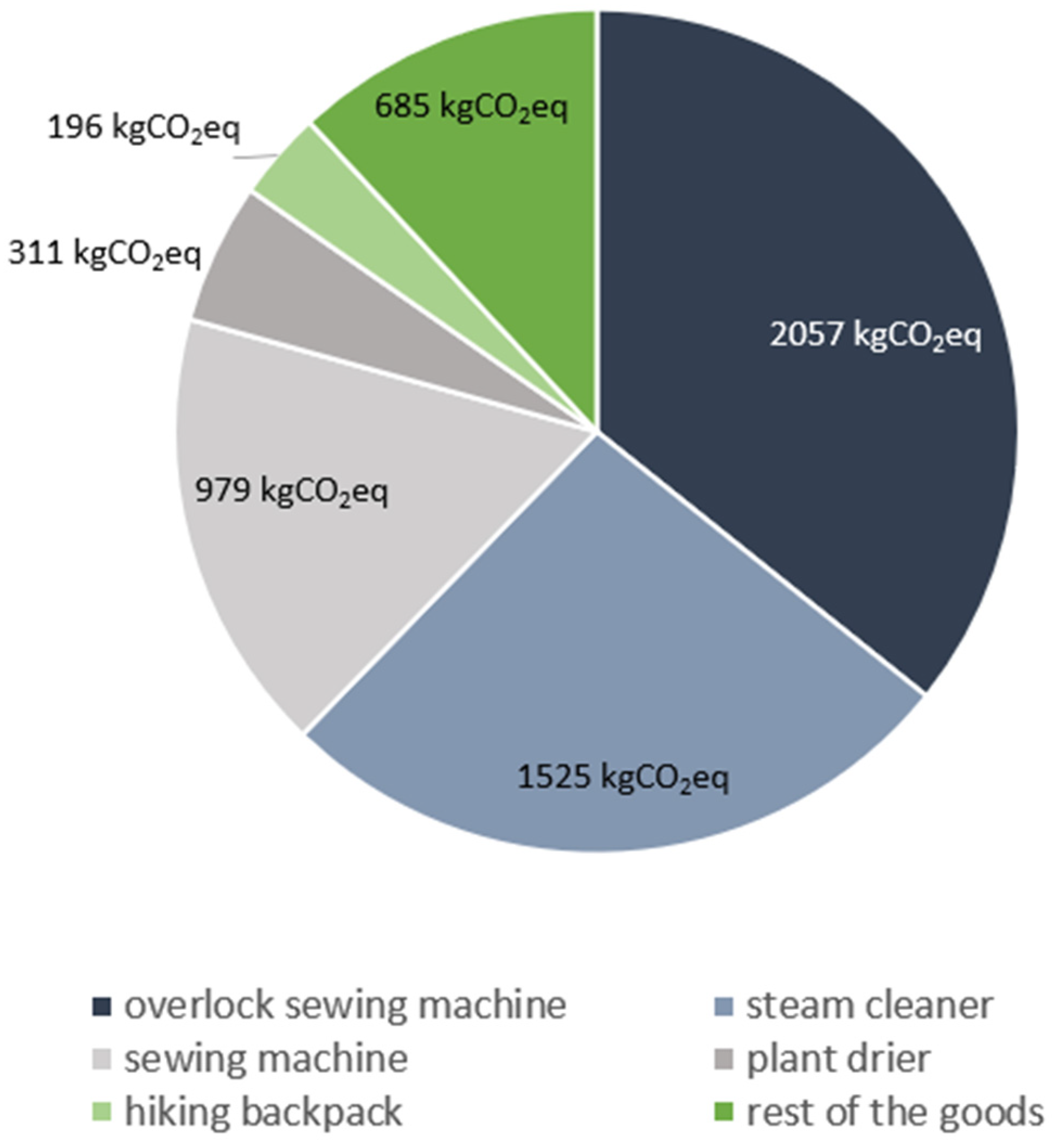

3.2. Assessing GHG Emission Reductions of the LoT

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- I am…

- Summer resident in Asikkala

- Summer resident in Hollola

- Resident of Asikkala

- Resident of Hollola

- I live elsewhere in a city

- I live elsewhere in rural areas

- Could you offer something for people living nearby? In the following questions we are mapping out which goods/spaces/skills you could offer to others, either for free or for a fee? Answering options include no/for free/for a fee.

- I could offer…

- (a)

- Extra living space, also for spending nights

- (b)

- Extra living space during daytime

- (c)

- Extra storage space (incl. vehicles)

- (d)

- Space for eg. woodworking or vehicle repairing

- (e)

- Space in the garden

- (f)

- Sauna

- I could offer…

- (a)

- A car

- (b)

- A boat

- (c)

- A motorcycle

- (d)

- An ATV

- (e)

- Gardening tools

- (f)

- Trailer

- (g)

- Tools

- (h)

- Cooking tools such as plant drier or juicer

- (i)

- Cleaning tools such as steam cleaner

- Which goods you would like to loan for yourself? Answering options include no/for free/for a fee.

- c.

- A car

- d.

- A boat

- e.

- A motorcycle

- f.

- An ATV

- g.

- Gardening tools

- h.

- Trailer

- i.

- Tools

- j.

- Cooking tools such as plant drier or juicer

- k.

- Cleaning tools such as steam cleaner

References

- Henry, M.; Schraven, D.; Bocken, N.; Frenken, K.; Hekkert, M.; Kirchherr, J. The Battle of the Buzzwords: A Comparative Review of the Circular Economy and the Sharing Economy Concepts. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2021, 38, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Closing the Loop—An EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52015DC0614 (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- A New Circular Economy Action Plan. For a Cleaner and More Competitive Europe. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1583933814386&uri=COM:2020:98:FIN (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Fitch-Roy, O.; Benson, D.; Monciardini, D. Going around in circles? Conceptual recycling, patching and policy layering in the EU circular economy package. Environ. Politics 2020, 29, 983–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vanhamäki, S.; Virtanen, M.; Luste, S.; Manskinen, K. Transition towards a circular economy at a regional level: Case study on closing biological loops. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 156, 104716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towards the Circular Economy Vol. 1: An Economic and Business Rationale for an Accelerated Transition. Available online: https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/assets/downloads/publications/Ellen-MacArthur-Foundation-Towards-the-Circular-Economy-vol.1.pdf (accessed on 9 March 2022).

- Ghisellini, P.; Cialani, C.; Ulgiati, S. A review on circular economy: The expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 114, 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchherr, J.; Reike, D.; Hekkert, M. Conceptualizing the circular economy: An analysis of 114 definitions. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 127, 221–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrichs, H. Sharing economy: A potential new pathway to sustainability. GAIA Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2013, 22, 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, H. Sharing Economy: Promote Its Potential to Sustainability by Regulation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Merli, R.; Preziosi, M.; Acampora, A. How do scholars approach the circular economy? A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korhonen, J.; Honkasalo, A.; Seppälä, J. Circular economy: The concept and its limitations. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 143, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarevic, D.; Valve, H. Narrating expectations for the circular economy: Towards a common and contested European transition. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2017, 31, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.J. Sharing Economy: A Pathway to Sustainability or a Nightmarish Form of Neoliberal Capitalism? Ecol. Econ. 2016, 121, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belk, R. Sharing Versus Pseudo-Sharing in Web 2.0. Anthropologist 2014, 18, 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markman, G.D.; Lieberman, M.; Leiblein, M.; Wei, L.Q.; Wang, Y. The Distinctive Domain of the Sharing Economy: Definitions, Value Creation, and Implications for Research. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 927–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boar, A.; Bastida, R.; Marimon, F. A Systematic Literature Review. Relationships Between the Sharing Economy, Sustainability and Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlagwein, D.; Schoder, D.; Spindeldreher, K. Consolidated, systemic conceptualization, and definition of the “sharing economy”. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2020, 71, 817–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mi, Z.; Coffman, D. The sharing economy promotes sustainable societies. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sutherland, W.; Jarrahi, M.H. The sharing economy and digital platforms: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 43, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuster Morell, M.; Espelt, R.; Renau Cano, M. Sustainable Platform Economy: Connections with the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; He, Y.; Ji, Q. Collaborative logistics network: A new business mode in the platform economy. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2022, 25, 791–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobble, M.M. Regulating innovation in the new economy. Res. Technol. Manag. 2015, 58, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.P.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy—A New Sustainability Paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- World Commission on Environment and Development. Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. United Nations. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Ober, J.; Karwot, J. Pro-Ecological Behavior: Empirical Analysis on the Example of Polish Consumers. Energies 2022, 15, 1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, O.; Kibbe, A.; Hartig, T.; Kaiser, F.G. Capturing the Environmental Impact of Individual Lifestyles: Evidence of the Criterion Validity of the General Ecological Behavior Scale. Environ. Behav. 2018, 50, 350–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Factors Affecting Green Purchase Behaviour and Future Research Directions. Int. Strategy Manag. Rev. 2015, 3, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cherry, C.E.; Pidgeon, N.F. Is sharing the solution? Exploring public acceptability of the sharing economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 195, 939–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelinkova, M.; Tetrevova, L.; Vavra, J.; Munzarova, S. The Sharing Economy in the Context of Sustainable Development and Social Responsibility: The Example of the Czech Republic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plewnia, F.; Edeltraud, G. Mapping the Sharing Economy for Sustainability Research. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 570–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M.; Foroudi, P.; Khodayari, M.; Fashami, R.Z.; Shahabaldini, Z.; Shahriari, E. Sharing Your Assets: A Holistic Review of Sharing Economy. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 140, 604–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussyadiah, I.P.; Pesonen, J. Impacts of peer-to-peer accommodation use on travel patterns. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 1022–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schor, J. Debating the sharing economy. J. Self-Gov. Manag. Econ. 2016, 4, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Makov, T.; Shepon, A.; Krones, J.; Gupta, C.; Chertow, M. Social and environmental analysis of food waste abatement via the peer-to-peer sharing economy. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deleøkonomiens Klimapotentiale. Available online: https://concito.dk/files/dokumenter/artikler/deleoekonomi_endelig_100615_2.pdf (accessed on 29 March 2022).

- Lettenmeier, M.; Liedtke, C.; Rohn, H. Eight Tons of Material Footprint—Suggestion for a Resource Cap for Household Consumtion in Finland. Resources 2014, 3, 488–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Makov, T.; Font Vivanco, D. Does the Circular Economy Grow the Pie? The Case of Rebound Effects from Smartphone Reuse. Front. Energy Res. 2018, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar, J.P.; Sayeras, J.M.; Rocafort, A.; Galiana, J. The irruption of Airbnb and its effects on hotel profitability: An analysis of Barcelona’s hotel sector. Intang. Cap. 2017, 13, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden, D.; Peattie, K.; Oke, A. Access Over Ownership: Case Studies of Libraries of Things. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lax, B. What Are These Things Doing in the Library? How a Library of Things Can Engage and Delight a Community. OLA Q. 2020, 26, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Söderholm, J. Borrowing Tools from the Public Library. J. Doc. 2016, 72, 140–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameli, N. Libraries of Things as a new form of sharing. Pushing the Sharing Economy. Des. J. 2017, 20, S3294–S3304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinku Network—Towards Carbon Neutral Municipalities. Available online: https://www.hiilineutraalisuomi.fi/en-US/Hinku (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- Ilmastotyö. Available online: https://asikkala.fi/asuminen-ja-ymparisto/ymparistonsuojelu/ilmastotyo/ (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Maallemuuttajat 2030. Available online: https://www.lab.fi/en/project/maallemuuttajat-2030 (accessed on 18 March 2022).

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 5th ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E. Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lune, H.; Berg, B.L. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences; Pearson: Harlow, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Nissinen, A.; Savolainen, H. Julkisten Hankintojen ja Kotitalouksien Kulutuksen Hiilijalanjälki ja Luonnonvarojen Käyttö; Finnish Environment Institute: Helsinki, Finland, 2019; p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego-Schmid, A.; Mendoza, J.M.F.; Jeswani, H.K.; Azapagic, A. Life cycle environmental impacts of vacuum cleaners and the effects of European regulation. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 559, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Schmid, A.; Mendoza, J.M.F.; Jeswani, H.K.; Azapagic, A. Life cycle environmental evaluation of kettles: Recommendations for the development of eco-design regulations in the European Union. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 625, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Brommer, E.; Stratmann, B.; Quack, D. Environmental impacts of different methods of coffee preparation. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2011, 35, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudelin, A.; Uusitalo, V.; Kareinen, E.; Callahan, S.; Efe, M.; Hakan, M. The Carbon Footprint Calculation Model for the CAMPAIGNers app. Deliverable 2.1 of the CAMPAIGNers Project Funded under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme; GA No: 101003815; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2022; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Finland. Population and Society. Available online: https://www.stat.fi/tup/suoluk/suoluk_vaesto_en.html#Population%20structure%20on%2031%20December (accessed on 22 May 2022).

| Activity | Topic | Date | Stakeholder Included |

|---|---|---|---|

| Survey | Sharing and service economy needs in rural Päijät-Häme | July–September 2019 | Permanent and temporary residents (n = 175) |

| Meeting | Discussion about survey results | 17 October 2019 | Asikkala municipality staff |

| Desktop research | Different lending services in Finland and internationally | October–December 2019 | Project team |

| Workshop | Lending service planning | 20 November 2019 | Asikkala residents |

| Meeting | Discussion on placing the lending service in a municipal main library | 11 December 2019 | Asikkala municipality and main library staff |

| Project-steering group meeting | Discussion and decision on the plans | 7 February 2020 | Project-steering group |

| Survey | More detailed survey about the content of the lending service | 17 February–9 March 2020 | Municipal library customers and residents (n = 25) |

| Meeting | Discussion about survey results, follow-up measures and lending service operation model | 25 March 2020 | Asikkala municipality and main library staff |

| Donation campaign | Goods for the lending service were collected through donation campaign | 6 April–15 May 2020 | Residents |

| Practical implementation | Building a shelf for the LoT | 19–20 May 2020 | Project team |

| Preparations of service implementation and content creation | Instructions and visual material were completed | 9 June 2020 | Project team and main library staff |

| Practical implementation | The shelf and the content were transported to the main library | 10 June 2020 | Project team, main library staff |

| Administrative activities at the municipal library | The goods were added to the library’s lending system and arranged on a shelf | 11–17 June 2020 | Main library staff |

| Opening ceremony | LoT was opened for municipal library customers | 18 June 2020 | Municipal library staff, residents and local media |

| Maintenance discussion via e-mail | Focus on how the maintenance of the goods will be assured | September 2020 | Main library director, the project team |

| Communication meeting | Discussion about communication activities to strengthen customers’ awareness of the LoT | 2 February 2021 | Main library director, project team |

| Meeting about continuation of operations | Discussion about how the municipal library will continue maintenance and possibly upgrade the LoT | 12 October 2021 | Main library director, the project team |

| COICOP 1 Class | Factor (kg CO2eq/EUR) | Good | Price (EUR) | Number of Loans |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C053 Household appliances | 0.4 | ice cream maker | 65.95 | 7 |

| plant drier | 55.50 | 15 | ||

| juicer | 79 | 6 | ||

| steam juicer | 59.90 | 1 | ||

| food processor | 92.15 | 1 | ||

| blender | 39.90 | 0 | ||

| C055 Tools and equipment for house and garden | 0.7 | drill | 89.90 | 2 |

| steam cleaner | 99 | 23 | ||

| sander | 29.95 | 6 | ||

| tree pruner | 92.15 | 0 | ||

| sewing machine | 99.90 | 17 | ||

| overlock sewing machine | 209.90 | 15 | ||

| C093 Other recreational equipment, gardens and pets | 0.4 | tent | 64 | 4 |

| FigureTwister | 6 | 2 | ||

| sleeping pad | 21.9 | 3 | ||

| travel bed | 78.90 | 1 | ||

| Monopoly | 38 | 1 | ||

| Pictionary | 34 | 1 | ||

| miniature chess game | 14.30 | 3 | ||

| doorway pull-up bar | 32 | 2 | ||

| hiking backpack | 69.90 | 8 | ||

| Trangia stove | 49.90 | 5 | ||

| exercise wheel | 6 | 0 | ||

| Total | 123 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Claudelin, A.; Tuominen, K.; Vanhamäki, S. Sustainability Perspectives of the Sharing Economy: Process of Creating a Library of Things in Finland. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6627. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116627

Claudelin A, Tuominen K, Vanhamäki S. Sustainability Perspectives of the Sharing Economy: Process of Creating a Library of Things in Finland. Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6627. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116627

Chicago/Turabian StyleClaudelin, Anna, Kaisa Tuominen, and Susanna Vanhamäki. 2022. "Sustainability Perspectives of the Sharing Economy: Process of Creating a Library of Things in Finland" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6627. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116627

APA StyleClaudelin, A., Tuominen, K., & Vanhamäki, S. (2022). Sustainability Perspectives of the Sharing Economy: Process of Creating a Library of Things in Finland. Sustainability, 14(11), 6627. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116627