The Impact of Social Media Information Sharing on the Green Purchase Intention among Generation Z

Abstract

:1. Introduction

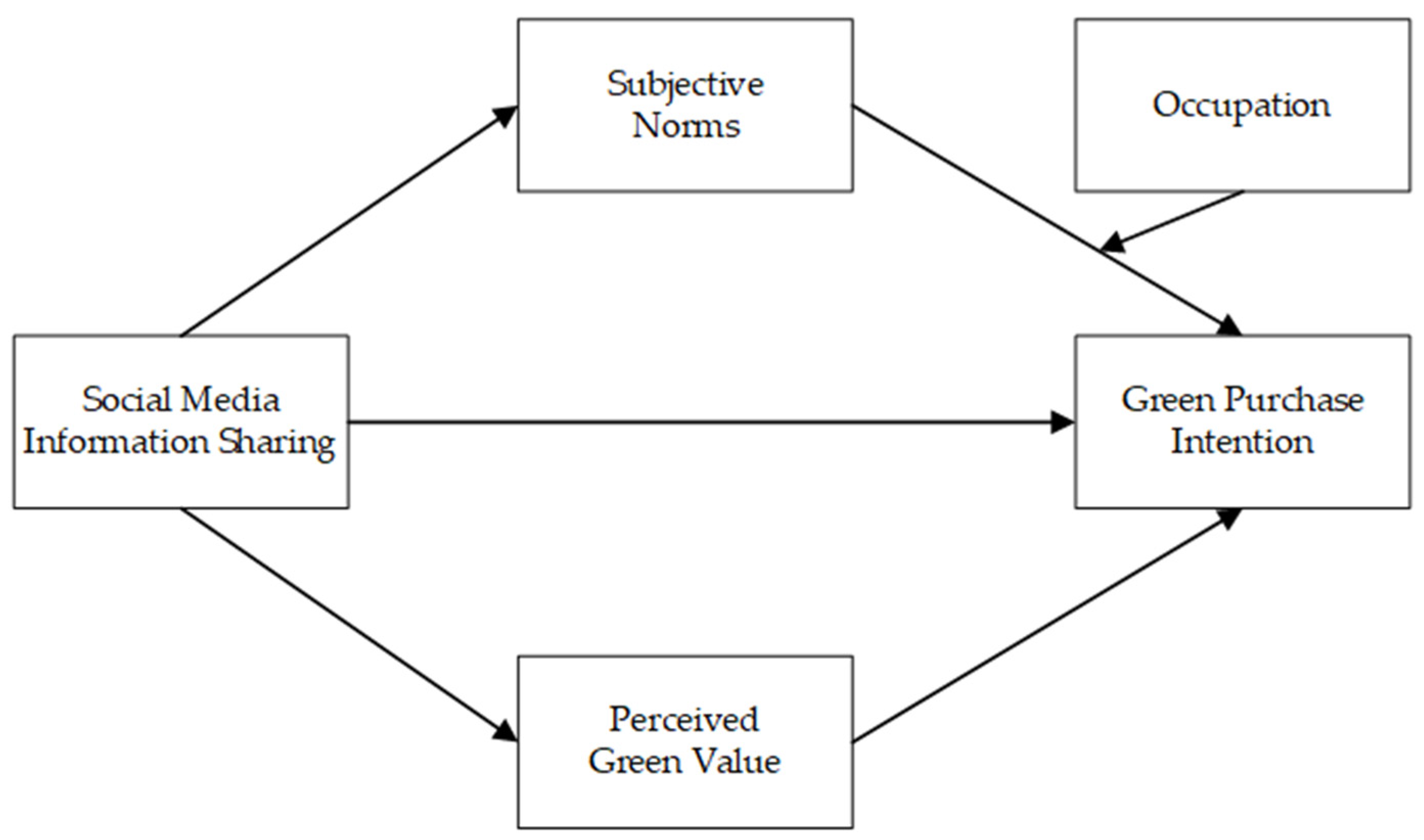

- Is there a positive relationship between social media information sharing and green purchase intention?

- Do subjective norms and perceived green value mediate between them?

- Does occupation play a moderating role in the relationship between subjective norms and green purchase intention?

- Based on SOR theory, this study explains the relationship between social media information sharing, subjective norms, perceived green value, and green product purchase intentions, enriching the research on SOR theory and adding subjective norms and perceived green value as the main mediating drivers and pathways of influence.

- The moderating effect of occupation is verified by the influence of subjective norms on the purchase intention of green products, thus enriching the research on green purchase intention and the research on the consumption field of Generation Z.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Generation Z

2.2. Stimulus–Organism–Response-Based View

2.3. Social Media Information Sharing

2.4. Social Media Information Sharing and Green Purchase Intention

2.5. The Influence of Perceived Green Value on Social Media Information Sharing and Green Purchase Intention

2.6. The Influence of Subjective Norms on Social Media Information Sharing and Green Purchase Intention

2.7. The Moderating Role of Consumer Occupation

3. Research Design

3.1. Sample and Data Selection

3.2. Analysis Techniques

4. Results

4.1. Reliability and Validity Analysis

4.2. Validation Factor Analysis

4.3. Common Method Deviation Test

4.4. Hypothesis Testing and Model Analysis

4.5. Mediating Effects Test

4.6. Test for Adjustable Mediating Effects

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

- There is a significant positive effect of social media information sharing on the direct path to green purchase intention. This finding supports the notion that “sharing and viewing positive information about the environment on social media can help increase the intention of Generation Z consumers to purchase green products” [35]. One reason for this result is that China is currently placing a lot of emphasis on environmental protection and encouraging the public to consume green products. Social media, as a public sharing platform, can meet the needs of internet users for social needs such as social interaction and information sharing. At the same time, companies are using social media as a sales channel to promote green ideas and green products. Most studies on green consumption focus on consumers’ reasons, examining the influence of consumer attitudes and environmental responsibility on green purchasing behavior. Biswas uses the TAM technology acceptance model as a framework and uses social media information sharing such as advertising, blogs, news, and mainstream opinions as mediating variables to investigate the influence of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use on consumers’ green purchasing behavior. The results show that when consumers’ perceived value is optimized, they can be motivated to promote green products on social media information sharing platforms, thereby increasing green product consumption behavior [45]. Based on SOR, this study uses social media information sharing as an external stimulus, confirming that social media information sharing has a positive impact on Generation Z’s green purchase intention, and to a certain extent inherits and expands previous research. It provides certain support for the successful implementation of China’s formulation of green consumption policies and related enterprises’ green product sales promotion with the help of Internet social media information sharing.

- Based on the results of the mediating effect, this study shows that social media information sharing influences the relationship between it and green purchase intention through two mediating variables: perceived green value and subjective norms, which in turn influence it. According to the results of the study, the direct effect of social media information sharing on green product purchase intention is significant, while there is an indirect effect of mediating variables. The mediating effect of social media information sharing–subjective norms–green purchase intention accounted for 59.90% of the total mediating effect; the mediating effect of social media information sharing–perceived green value–green purchase intention accounted for 40.10% of the total mediating effect, while the mediating effect of subjective norms and perceived green value in the two mediating effects of social media information sharing on green purchase intention was not significant. The difference between subjective norms and perceived green value in the two mediating effects of social media information sharing on green purchase intention was not significant. Therefore, when consumers have strong subjective norms and perceived green value for sharing environmental information on social media, both can increase consumers’ willingness to consume green products. On the one hand, perceived green value partially mediates the relationship between social media information sharing and green purchase intention. Previous studies have shown that consumers’ perceived green value has a positive effect on green product purchase intention [11]. In addition to the perceived functional value of the product, consumers’ purchase of green products also stems from their perception of environmental ecology [25]. Furthermore, Lee [69] pointed out that altruism helps Hong Kong youths engage in green purchasing behavior in the social environment of the Internet. Green product retailers can make use of social media information sharing communication channels to promote environmental information and increase the public’s perceived green value, thus increasing green purchase intention [61]. Therefore, green messages appearing in social media information sharing can help to enhance consumers’ perception of environmental ecology and their willingness to pay for it, thus leading to green consumption. Although previous studies were conducted in a different context than the present study, they overlap with the current results in that perceived green value mediates the relationship between social media information sharing and green purchase intention. On the other hand, subjective norms partially mediated the relationship between social media information sharing and green product purchase intentions. Consumers’ subjective norms have a positive effect on green purchase intention [65,66]. In previous studies on the causes and consequences of subjective norms, on the one hand, collectivist values are an important contributing factor to subjective norms. At the same time, environmental behaviors on social media can serve as a model to help shape public awareness of environmental protection. However, the potential impact of subjective norms as an effective mediator of green purchase intention is ignored. This study correlates the sharing and dissemination of environmental protection information in social media with subjective norms and green product purchase intentions, confirming that subjective norms have a certain mediating effect. In conclusion, this study aims to explore the influence of social media information sharing on green product purchase intention under the dual mediation effect of perceived green value and subjective norms through the SOR framework. The state and related enterprises can continuously tap the potential of social media to provide green environmental protection information, improve consumers’ perceived green value and subjective norms of green products, increase their purchasing intentions for green products, and achieve the goal of overall green consumption in society.

- The regression results of the moderating effect show that consumers’ green purchase intention and the interaction term between occupation and subjective norms are significant, which demonstrates that there is a difference in the effect of subjective norms on the green purchase intention between student and non-student consumers. The results of the study confirm that the mediating effect of subjective norms on green purchase intention varies across different occupational groups of Generation Z. Previous studies have analyzed the impact of social media information sharing on consumers’ green purchase intention [31], but no research has been conducted to discuss basic consumer characteristics. The study limited the use of green products to female consumers, who were confirmed to be more likely to purchase green products than men [93]. However, the sample was not further categorized by occupation. This study is inconsistent with the methodology of previous studies, as this paper focuses on dividing Generation Z into non-student and student groups, due to the use of a dichotomous definition of dummy variables (non-student = 0; student = 1). The negative moderating effect of occupation on the relationship between subjective norms and green purchasing intentions was highlighted, i.e., non-student groups were more strongly driven by subjective norms than student groups. In a further moderating effect test, the non-student Generation Z cohort showed a significant positive moderating effect on the relationship between subjective norms and green purchase intention. The student Generation Z cohort, on the other hand, did not have a significant moderating effect on the relationship between subjective norms and green purchase intention. Under the moderating effect of low subjective norms, students had greater green purchase intention than non-students; while under the moderating effect of high subjective norms, non-students had greater green purchase intention than students. It is clear that increasing the moderating effect of subjective norms significantly increased the non-student group’s green purchase intention, while the student group shows no significant change in their green purchase intention. One possible explanation is that consumers make product purchase decisions that are consciously tailored to the expectations of their group. Non-student consumers are more sensitive to the moderating effect of subjective norms than students due to their different social roles. This group with high subjective norms is more concerned with social acceptance and wants to increase their acceptance and reputation in the social group through their green consumption behavior. Another explanation is that, although green products are relatively more expensive than non-green products, the effect of income on occupation is not significant. As China’s overall economic level increases, students have relatively ample pocket money, which is mainly used for personal expenses, while their families are less burdened and their household living expenses are relatively smaller than those of non-student groups. As a result, students’ green purchase intention is generally at a medium to a high level, and, overall, this group has a strong intention to consume green products.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

- Based on stimulus–organism–response (SOR) theory, this study emphasizes the important mechanism of action of stimuli from social media information sharing combined with individual consumers’ perceived green value and subjective norms as the external–internal combination of green purchase intention, takes perceived green value and subjective norms as dual mediating variables, enriches the path of social media information sharing–green purchase intention, studies the moderating role of occupation, and enriches the research perspective in the field of green consumption. Previous research on green consumption mainly focused on the driving role of the external macro-environment, such as consumer attitudes, personal responsibility, or policies, ignoring the influence of internal and external interactions. Based on SOR, this study contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the role of social media information sharing in facilitating the purchase intention of green products.

- The consumer behavior of Generation Z is becoming an important research topic; however, past research has focused on this age group as a demographic characteristic and has rarely examined this group as a subject of study. In contrast, this article focuses on the influence of social media information sharing, subjective norms, and perceived green value on the purchase of green products from the perspective of the young Z generation, which can effectively fill the gap in this area of research.

- To further examine Generation Z, this study also explores the moderating effect of occupation on subjective norms and green purchase intention, and the pathway of subjective norms–green purchase intention from a consumer perspective. To our knowledge, no research has examined the moderating power of Generation Z’s occupations in the context of green purchase intention and subjective norms. This study fills this gap and enriches the research on green consumption in this group.

5.3. Practical Implications

- The government should actively respond to the guiding policies for green, low-carbon, and circular development issued by the state. On the one hand, it should strengthen the guidance and subsidies for enterprises and residents to purchase green products and encourage the consumption of green products. Mainstream media should focus on building online green communities, creating green consumption-oriented topical bloggers, WeChat public accounts, and other opinion leaders to spread the correct concept of green consumption to the audience, which is conducive to the formation of Generation Z green consumer group norms, and actively guide green consumption behavior and lifestyle. Through publicity and education on green consumption of all employees, awareness of green consumption in the whole society will be improved, a green and low-carbon lifestyle will be advocated, the perception and recognition of green products will be improved, and a social atmosphere of green consumption will be created. On the other hand, improve the production system of green, low-carbon, and circular development. Through fiscal and taxation support, the development of green and environment-protecting industries will be promoted, and enterprises will be encouraged to take green products as a new direction for future product development and transformation, meeting the market demand for green and environmentally friendly products, improving and introducing green production technology, improving existing products and services, and reducing environmental pollution.

- For their part, companies should take the initiative to seize the opportunity for green innovation and promote the green transformation of their industries to cope with the increasingly severe environmental challenges and the relevant environmental regulations introduced by the state. As Generation Z is generally more environmentally conscious and pays attention to brands’ senses of social responsibility and social performance when shopping for goods, companies should focus on integrating green concepts into their branding, improve green product attributes, and develop green products that meet customer needs to achieve both economic and ecological benefits. Social media information sharing is a powerful carrier of green product information and can be an important channel for promoting green topics and motivating green consumption. Proper use of social media information-sharing platforms to promote green products can boost consumers’ purchase intention for green products. Furthermore, research findings show that consumers’ occupations impact their green purchase intention, so companies should target different consumer groups when developing marketing plans in order to achieve precise marketing.

- On the consumer side, consumers are an important part of society, and their willingness to purchase green products is an important manifestation of participating in improving environmental issues. It is not only the government and its relevant departments that need to actively educate consumers on environmental protection but also enterprises to make the green transition to supply green products to the market, on the basis of which the green consumption behavior of consumers also has an exemplary role to play. Social media information sharing is not only a social communication channel but can also influence consumers’ purchasing decisions through the information it carries. When consumers share their experiences of using green products or retweet positive environmental topics on social media, it enhances the perceived green value of green products to other users on social media sharing and creates a subjective normative effect that encourages other users to emulate green consumption behavior, thus contributing to a positive social atmosphere. This requires consumers to take the initiative to recognize the importance of their own consumption behavior to the cause of environmental protection and to take on the responsibility and mission of social citizenship in sustainable development planning.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

- The article takes the Z generation as the research object, and conducts research in the form of questionnaires. For the whole country, there may be some deviations in the data. Further research can be carried out by taking the region where the consumer is located or the specific industry the consumer is engaged in as an influencing factor for green product purchases.

- The dependent variable of the study is the purchase intention of green products, but the negative interference of social approval bias on the data analysis results cannot be completely avoided. The next step of research can consider conducting controlled experiments or observing consumers who have implemented purchasing behaviors to further analyze purchasing motivation.

- The link between social media and corporate performance has not been studied in-depth in this paper, and future research could try to start from the perspective of knowledge sharing and knowledge management, which may provide more insights.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cai, W.G.; Zhou, X.L. On the drivers of eco-innovation: Empirical evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 79, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jian, Y.; Yu, I.Y.; Yang, M.X.; Zeng, K. The impacts of fear and uncertainty of COVID-19 on environmental concerns, brand trust, and behavioral intentions toward green hotels. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratianu, C.; Bejinaru, R. COVID-19 induced emergent knowledge strategies. Knowl. Process Manag. 2021, 28, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Global Sustainable Development Report. 2019. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/24797GSDR_report_2019.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Rex, E.; Baumann, H. Beyond ecolabels: What green marketing can learn from conventional marketing. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qi, G.Y.; Shen, L.Y.; Zeng, S.X.; Jorge, O. The drivers for contractors’ green innovation: An industry perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1358–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, H.; Galle, W.P. Green purchasing strategies: Trends and implications. Int. J. Pur. Mater. Manag. 1997, 33, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumers who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Groot, J.I.; Steg, L. Relationships between value orientations, self-determined motivational types and pro-environmental behavioural intentions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniëls, M.C.J.; Lambrechts, W.; Platje, J.; Motylska-Kuźma, A.; Fortuński, B. 50 Shades of Green: Insights into Personal Values and Worldviews as Drivers of Green Purchasing Intention, Behaviour, and Experience. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gärling, T.; Fujii, S.; Gärling, A.; Jakobsson, C. Moderating effects of social value orientation on determinants of proenvironmental behavior intention. J. Environ. Psych. 2003, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, J.; Tang, Y.; Qing, P.; Li, H.; Razzaq, A. Donation or Discount: Effect of Promotion Mode on Green Consumption Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murwaningtyas, F.; Harisudin, M.; Irianto, H. Effect of Celebrity Endorser Through Social Media on Organic Cosmetic Purchasing Intention Mediated with Attitude. Knowl. Soc. Sci. 2020, 6, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbert, R.L.; Kwak, N.; Shah, D.V. Environmental concern, patterns of television viewing, and pro-environmental behaviors: Integrating models of media consumption and effects. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2003, 47, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keng, C.J.; Ting, H.Y. The acceptance of blogs: Using a customer experiential value perspective. Int. Res. 2009, 19, 479–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C.; Lin, C.P. Understanding the effect of social media marketing activities: The mediation of social identification, perceived value, and satisfaction. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 140, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangold, W.G.; Faulds, D.J. Social media: The new hybrid element of the promotion mix. Bus. Horiz. 2009, 52, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974; pp. 86–108. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Ph. Rhetoric; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1977; Volume 10, pp. 130–132. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.K. A comparative study of green purchase intention between Korean and Chinese consumers: The moderating role of collectivism. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abrams, D.; Ando, K.; Hinkle, S. Psychological attachment to the group: Cross-cultural differences in organizational identification and subjective norms as predictors of workers’ turnover intentions. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 24, 1027–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Podoshen, J.S.; Li, L.; Zhang, J. Materialism and conspicuous consumption in China: A cross-cultural examination. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2011, 35, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waugh, C.E.; Fredrickson, B.L. Nice to know you: Positive emotions, self–other overlap, and complex understanding in the formation of a new relationship. J. Posit. Psychol. 2006, 1, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalas, J.E.; Stern, B.B. Sympathy and empathy: Emotional responses to advertising dramas. J. Consum. Res. 2003, 29, 566–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Enhance green purchase intentions: The roles of green perceived value, green perceived risk, and green trust. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.S.; Chen, C.Y.; Chen, H.K.; Hsieh, T. A study of relationships among green consumption attitude, perceived risk, perceived value toward hydrogen-electric motorcycle purchase intention. Aasri Procedia 2012, 2, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Huang, Q.; Zhong, X.; Davison, R.M.; Zhao, D. The influence of peer characteristics and technical features of a social shopping website on a consumer’s purchase intention. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2016, 36, 1218–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, R.Y.; Lau, L.B. Explaining green purchasing behavior: A cross-cultural study on American and Chinese consumers. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2002, 14, 9–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelkar, M.; Coleman, L.J.; Bahnan, N.; Manago, S. Green consumption or green confusion. J. Strateg. Innov. Sustain. 2014, 9, 41. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, L.J.; Bahnan, N.; Kelkar, M.; Curry, N. Walking the walk: How the theory of reasoned action explains adult and student intentions to go green. J. Appl. Bus. Res. (JABR) 2011, 27, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pop, R.A.; Săplăcan, Z.; Alt, M.A. Social media goes green—The impact of social media on green cosmetics purchase motivation and intention. Information 2020, 11, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffett, R. The YouTube marketing communication effect on cognitive, affective and behavioural attitudes among Generation Z consumers. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. 57 Fascinating and Incredible YouTube Statistics. Available online: https://www.brandwatch.com/blog/youtube-stats (accessed on 17 April 2022).

- Bolton, R.N. Understanding Generation Y and their use of social media: A review and research agenda. J. Serv. Manag. 2013, 24, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bedard, S.A.N.; Tolmie, C.R. Millennials’ green consumption behaviour: Exploring the role of social media. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 1388–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelman, H.C. Compliance, identification, and internalization three processes of attitude change. J. Confl. Resolut. 1958, 2, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacoby, J. Stimulus-organism-response reconsidered: An evolutionary step in modeling (consumer) behavior. J. Consum. Psychol. 2002, 12, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Kim, Y.G. Application of the stimuli-organism-response (SOR) framework to online shopping behavior. J. Internet Commer. 2014, 13, 159–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, L.N. Creating a satisfying internet shopping experience via atmospheric variables. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2004, 28, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lennon, S.J. Effects of reputation and website quality on online consumers’ emotion, perceived risk and purchase intention: Based on the stimulus-organism-response model. J. Res. Int. Mark. 2013, 7, 33–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D.M.; Ellison, N.B. Social network sites: Definition, history, and scholarship. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2007, 13, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greer, C.F.; Ferguson, D.A. Using Twitter for promotion and branding: A content analysis of local television Twitter sites. J. Broadcasting Electron. Media 2011, 55, 198–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, G. Understanding the appeal of user-generated media: A uses and gratification perspective. Internet Res. 2009, 19, 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.Y.M.; Kim, J. Online customer relationship marketing tactics through social media and perceived customer retention orientation of the green retailer. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. Int. J. 2017, 21, 298–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, K.; Chen, Y.; Kaplan, A.M.; Ognibeni, B.; Pauwels, K. Social media metrics—A framework and guidelines for managing social media. J. Int. Mark. 2013, 27, 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, L.P. Does social media influence consumer buying behavior? An investigation of recommendations and purchases. J. Bus. Econ. Res. (JBER) 2013, 11, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luqman, A.; Masood, A.; Shahzad, F.; Feng, Y. Untangling the adverse effects of late-night usage of smartphone-based SNS among University students. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2021, 40, 1671–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista. YouTube—Statistics & Facts. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/2019/youtube/ (accessed on 17 April 2022).

- Statista. Number of Social Network Users Worldwide from 2017 to 2025. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/278414/number-of-worldwide-social-network-users/ (accessed on 17 April 2022).

- Gao, Q.; Abel, F.; Houben, G.J.; Yu, Y. A Comparative Study of Users’ Microblogging Behavior on Sina Weibo and Twitter. In Proceedings of the International Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization, Montreal, QC, Canada, 16–20 July 2012; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zafar, A.U.; Shen, J.; Shahzad, M.; Islam, T. Relation of impulsive urges and sustainable purchase decisions in the personalized environment of social media. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 25, 591–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idowu, S.O.; Capaldi, N.; Zu, L.; Gupta, A.D. Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 56–102. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, P.H.; Lin, G.Y.; Zheng, Y.L.; Chen, Y.C.; Chen, P.Z.; Su, Z.C. Exploring the effect of Starbucks’ green marketing on consumers’ purchase decisions from consumers’ perspective. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 56, 102162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junsheng, H.; Akhtar, R.; Masud, M.M.; Rana, M.S.; Banna, H. The role of mass media in communicating climate science: An empirical evidence. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 238, 117934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.N.; Newman, B.I.; Gross, B.L. Why we buy what we buy: A theory of consumption values. J. Bus. Res. 1991, 22, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kustono, A.S.; Nanggala, A.Y.A.; Mas’ud, I. Determinants of the Use of E-Wallet for Transaction Payment among College Students. J. Econ. Bus. Account. Ventur. 2020, 23, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, A.; Tang, Y.; Qing, P. Towards Sustainable Diets: Understanding the Cognitive Mechanism of Consumer Acceptance of Biofortified Foods and the Role of Nutrition Information. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaman, L. Opportunities for green marketing: Young consumers. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2008, 26, 573. [Google Scholar]

- Van Boven, L.; Kane, J.; McGraw, A.P.; Dale, J. Feeling close: Emotional intensity reduces perceived psychological distance. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- De Lenne, O.; Vandenbosch, L. Media and sustainable apparel buying intention. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2017, 21, 483–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, M.; Isherwood, B. The World of Goods, 1st ed.; Routledge Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 3–146. [Google Scholar]

- Elahi, E.; Zhang, H.; Lirong, X.; Khalid, Z.; Xu, H. Understanding cognitive and socio-psychological factors determining farmers’ intentions to use improved grassland: Implications of land use policy for sustainable pasture production. Land Use Policy 2021, 102, 105250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K. Mass communication and pro-environmental behaviour: Waste recycling in Hong Kong. J. Environ. Manag. 1998, 52, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer “attitude–behavioral intention” gap. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, U.C.; Ndubisi, N.O. Green buyer behavior: Evidence from Asia consumers. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2013, 48, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A.L.; Olsen, J.E.; Granzin, K.L.; Burns, A.C. An investigation of determinants of recycling consumer behavior. ACR N. Am. Adv. 1993, 20, 481–487. [Google Scholar]

- Chwialkowska, A. How Sustainability Influencers Drive Green Lifestyle Adoption on Social Media: The Process of Green Lifestyle Adoption Explained through the Lenses of the Minority Influence Model and Social Learning Theory. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 11, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K. The green purchase behavior of Hong Kong young consumers: The role of peer influence, local environmental involvement, and concrete environmental knowledge. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2010, 23, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.H.; Gao, Q.; Wu, Y.P.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, X.D. What affects green consumer behavior in China? A case study from Qingdao. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, E.; Khalid, Z.; Zhang, Z. Understanding farmers’ intention and willingness to install renewable energy technology: A solution to reduce the environmental emissions of agriculture. Appl. Energy 2022, 309, 118459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamundo, P.J.; Kopelman, R.E. The moderating effects of occupation, age, and urbanization on the relationship between job satisfaction and life satisfaction. J. Vocat. Behav. 1980, 17, 106–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, D.; Hogg, M.A. Social Identifications: A Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations and Group Processes, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2006; pp. 175–223. [Google Scholar]

- Bettman, J.R.; Luce, M.F.; Payne, J.W. Constructive consumer choice processes. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 25, 187–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmiento, C.V.; El Hanandeh, A. Customers’ perceptions and expectations of environmentally sustainable restaurant and the development of green index: The case of the Gold Coast, Australia. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 15, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, P.; Hansen, E.N.; Kangas, J.; Laukkanen, T. How national culture and ethics matter in consumers’ green consumption values. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 265, 121754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Long, R.; Chen, H.; Sun, K.; Li, Q. Exploring public attention about green consumption on Sina Weibo: Using text mining and deep learning. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 30, 674–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Chen, H.; Long, R.; Wang, Y.; Hou, C.; Liu, B. Will the public pay for green products? Based on analysis of the influencing factors for Chinese’s public willingness to pay a price premium for green products. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 61408–61422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Tsai, C.F. The relationship between brand image and purchase intention: Evidence from award winning mutual funds. Int. J. Bus. Financ. Res. 2014, 8, 27–40. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Muller, D.; Judd, C.M.; Yzerbyt, V.Y. When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 89, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Chan, J.; Tan, B.C.; Chua, W.S. Effects of interactivity on website involvement and purchase intention. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2010, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Kallgren, C.A.; Reno, R.R. A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1991; pp. 201–234. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. Adv. Int. Mark. 2009, 20, 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson Education International: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelezny, L.C.; Chua, P.P.; Aldrich, C. Elaborating on gender differences in environmentalism. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 443–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Occupation | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Non-student | 143 | 0.522 |

| Student | 131 | 0.478 |

| Education | ||

| Below high school | 8 | 0.029 |

| High school | 8 | 0.029 |

| Bachelor | 228 | 0.832 |

| Master and above | 30 | 0.110 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 134 | 0.489 |

| Female | 140 | 0.511 |

| Age | ||

| <18 | 8 | 0.029 |

| 18–21 | 206 | 0.752 |

| 22–24 | 41 | 0.150 |

| 25–27 | 19 | 0.069 |

| Income | ||

| <1000 | 6 | 0.022 |

| 1000–4000 | 91 | 0.332 |

| 4001–7000 | 149 | 0.544 |

| Above 7001 | 28 | 0.102 |

| Items |

|---|

| Social media information sharing (SMIS) |

| 1. I can use social media information sharing to interact with others about green products. |

| 2. My engagement with environmental topics on social media sharing has influenced my green product purchases. |

| 3. The eco-friendly information shared in social media messages was able to give me easier access to information or feedback on green products. |

| 4. On social media, information sharing content about green products is worthwhile and trusted. |

| Green purchase intention (GPI) |

| 1. I will gather and learn more about this green product. |

| 2. I would recommend this green product to others. |

| 3. I will consider purchasing this green product when needed. |

| 4. Sharing information on social media will prompt me to buy a green product. |

| Perceived green value (PGV) |

| 1. Buy green products because of the better environmental benefits. |

| 2. The eco-friendly features of the green product are value for the money for me. |

| 3. The environmental performance of the green product meets my expectations. |

| Subjective norms (SN) |

| 1. I think green and energy-efficient products are more in line with social development. |

| 2. I think green and energy-efficient products are more in line with my family’s wishes. |

| 3. I think green and energy-efficient products are more in line with national policy. |

| Variables | Items | Factor Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMIS | SMIS1 | 0.771 | 0.924 | 0.893 | 0.676 |

| SMIS2 | 0.869 | ||||

| SMIS3 | 0.841 | ||||

| SMIS4 | 0.805 | ||||

| GPI | GPI1 | 0.829 | 0.912 | 0.892 | 0.675 |

| GPI2 | 0.792 | ||||

| GPI3 | 0.859 | ||||

| GPI4 | 0.804 | ||||

| PGV | PGV1 | 0.742 | 0.782 | 0.787 | 0.557 |

| PGV2 | 0.867 | ||||

| PGV3 | 0.606 | ||||

| SN | SN1 | 0.872 | 0.919 | 0.891 | 0.733 |

| SN2 | 0.863 | ||||

| SN3 | 0.833 |

| Education | Age | Gender | SMIS | GPI | PGV | SN | Occupation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education | ||||||||

| Age | 0.191 ** | |||||||

| Gender | −0.144 ** | 0.0851 | ||||||

| Income | −0.015 | 0.223 *** | 0.117 * | |||||

| SMIS | 0.106 ** | 0.009 | 0.104 * | 0.822 | ||||

| GPI | 0.049 | 0.085 | 0.215 ** | 0.566 *** | 0.821 | |||

| PGV | 0.099 * | 0.044 | 0.111 * | 0.592 *** | 0.502 *** | 0.746 | ||

| SN | 0.059 | −0.114 * | 0.218 *** | 0.534 *** | 0.538 *** | 0.496 *** | 0.856 | |

| Occupation | −0.07 | 0.247 | −0.074 | −0.145 ** | −0.102 * | −0.076 | −0.485 *** | |

| Mean | 2.022 | 1.259 | 0.489 | 5.764 | 6.008 | 6.257 | 5.462 | 0.478 |

| SD | 0.506 | 0.625 | 0.501 | 1.053 | 0.905 | 0.766 | 1.141 | 0.5 |

| Model | X2 | df | X2/df | RMSEA | CFI | GFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-factor model | 108.971 | 57 | 1.912 | 0.058 | 0.983 | 0.949 |

| Three-factor model | 156.887 | 60 | 2.615 | 0.077 | 0.968 | 0.926 |

| Two-factor model | 212.291 | 64 | 3.317 | 0.092 | 0.950 | 0.898 |

| One-factor model | 300.020 | 65 | 4.616 | 0.115 | 0.921 | 0.862 |

| Variable | GPI | PGV | SN | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | M8 | M9 | M10 | |

| Control | ||||||||||

| Constant | 5.332 *** | 3.021 *** | 2.512 *** | 1.997 *** | 2.150 *** | 5.629 *** | 3.567 *** | 4.585 *** | 1.932 *** | |

| Education | 0.133 | 0.001 | −0.037 | −0.017 | 0.031 | 0.180 | 0.063 | 0.297 ** | 0.146 | |

| Age | 0.056 | 0.096 | 0.177 ** | 0.089 | 0.063 | −0.012 | 0.023 | −0.354 ** | −0.308 ** | |

| Gender | 0.389 *** | 0.275 ** | 0.168 | 0.253 ** | 0.288 ** | 0.180 | 0.078 | 0.536 *** | 0.406 ** | |

| Income | 0.085 | 0.007 | −0.040 | −0.005 | 0.023 | 0.111 | 0.04 | 0.267 ** | 0.176 ** | |

| Independent variable | ||||||||||

| SMIS | 0.471 *** | 0.329 *** | 0.351 *** | 0.421 *** | 0.541 *** | |||||

| Mediator variable | ||||||||||

| PGV | 0.264 *** | 0.565 *** | ||||||||

| SN | 0.287 *** | 0.426 *** | ||||||||

| R2 | 0.059 | 0.349 | 0.387 | 0.422 | 0.28 | 0.319 | 0.035 | 0.357 | 0.103 | 0.343 |

| ∆R2 | 0.290 | 0.038 | 0.363 | 0.221 | 0.259 | 0.322 | 0.240 | |||

| F | 4.252 | 28.790 | 28.140 | 32.495 | 20.891 | 25.083 | 2.416 | 29.728 | 7.717 | 28.003 |

| Path | Effect | SE | Bootstrapping | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bias-Corrected | Percentile | |||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||

| GPI | 0.472 | 0.062 | Total Effect | |||

| 0.3488 | 0.5941 | 0.3488 | 0.5941 | |||

| PGV | 0.207 | 0.048 | Indirect Effect | |||

| SN | 0.1215 | 0.3102 | 0.1177 | 0.3004 | ||

| SMIS | 0.265 | 0.078 | Direct Effect | |||

| 0.1104 | 0.4193 | 0.1104 | 0.4193 | |||

| SIE | Effect | SE | Bias-Corrected | Percentile | Result of Hypothesis Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | ||||

| SMIS-PGV-GPI | 0.083 | 0.034 | 0.023 | 0.156 | 0.02 | 0.155 | Accept H6 |

| SMIS-SN-GPI | 0.124 | 0.03 | 0.072 | 0.192 | 0.065 | 0.185 | Accept H7 |

| Difference | −0.042 | 0.043 | −0.127 | 0.043 | −0.122 | 0.048 | - |

| Variable | GPI | SN | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M1 | M2 | M3 | M4 | M5 | M6 | M7 | |

| Control | |||||||

| Constant | 5.332 *** | 5.737 *** | 5.845 *** | 5.475 *** | 5.498 *** | 4.585 *** | 5.05 *** |

| Education | 0.133 | 0.001 | −0.037 | 0.006 | −0.034 | 0.297 ** | 0.146 |

| Age | 0.056 | 0.096 | 0.177 ** | 0.086 | 0.107 | −0.354 ** | −0.308 ** |

| Gender | 0.389 *** | 0.275 ** | 0.168 | 0.159 | 0.036 | 0.536 *** | 0.406 ** |

| Income | 0.085 | 0.007 | −0.04 | 0.102 | 0.084 | 0.267 ** | 0.176 * |

| Independent variable | |||||||

| SMIS | 0.471 *** | 0.329 *** | 0.303 *** | 0.229 *** | 0.541 *** | ||

| Moderator variable | |||||||

| Occupation | 0.330 * | 0.330 ** | |||||

| Mediator variable | |||||||

| SN | 0.263 *** | 0.329 *** | 0.611 *** | ||||

| Interaction term | |||||||

| Occupation × SN | −0.447 *** | ||||||

| R2 | 0.059 | 0.349 | 0.422 | 0.435 | 0.486 | 0.103 | 0.343 |

| ∆R2 | 0.059 | 0.29 | 0.072 | 0.014 | 0.051 | 0.103 | 0.24 |

| F | 4.252 | 28.79 | 32.476 | 29.306 | 31.376 | 7.717 | 28.003 |

| Subjective Norms | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderator Variable | Conditional Mediation | Boot SE | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

| Non-student | 0.353 | 0.051 | 0.259 | 0.462 |

| Student | 0.087 | 0.049 | −0.009 | 0.187 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, Y.; Xing, J. The Impact of Social Media Information Sharing on the Green Purchase Intention among Generation Z. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6879. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116879

Sun Y, Xing J. The Impact of Social Media Information Sharing on the Green Purchase Intention among Generation Z. Sustainability. 2022; 14(11):6879. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116879

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Yongbo, and Jiayuan Xing. 2022. "The Impact of Social Media Information Sharing on the Green Purchase Intention among Generation Z" Sustainability 14, no. 11: 6879. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14116879