1. Introduction

In the literature on the subject, there has been an interesting discussion for years on the importance of seasonality in tourism and its impact on the functioning of tourist enterprises, local markets, economies, and society [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. It provides extensive knowledge about the reasons for the occurrence of seasonality, its course, and the effects it causes. Seasonality is manifested, among others, by difficulties in adjusting the prices of tourist services during the year [

9,

10], the emergence of seasonal employment and unemployment [

1,

5,

11], an excessive burden on the natural environment of tourist destinations during peak season periods, and social tensions [

12]. Empirical analyses use methods that allow for the precise determination of periods of increases and decreases in tourism demand. These studies indicate, inter alia, the negative effects of seasonality on economies and local communities and emphasize that the mechanisms limiting the seasonality of tourism demand are still not very effective [

13,

14,

15]. Discussion on the importance of seasonality in tourism is still relevant and necessary, mainly due to the growing significance of tourism in economies, especially at the local level, and a large number of links between tourism and other industries. An additional motivation is the still-low effectiveness of activities limiting seasonality in the tourism sector.

The seasonality of tourism demand affects the size and structure of the business sector in the tourism industry and is a natural condition for their operation. There is strong evidence that seasonal fluctuations in tourism demand trigger immediate decisions by tourist enterprises, and a large proportion of them make decisions solely based on seasonal information [

10,

16,

17,

18]. Ferrante, Magno, and De Cantis (2018), based on aggregated data, unequivocally indicated that, in European countries, the tourism industry is facing the phenomenon of seasonality [

6]. Andriotis (2005) found that one-third of the tourist enterprises in Crete are enterprises that operate only during the tourist season. Treating seasonality as a natural phenomenon limits their economic activity. The remaining part of the tourist enterprises, i.e., two-thirds of the surveyed group of enterprises, operate all year round [

3]. Joliffe and Farnsworth (2003) pointed out that the seasonality of tourism demand is the main factor considered by tourist companies when defining human resource management strategies on Canada’s east coast [

4]. Martin and Martines (2020), based on data on tourist enterprises in Spain, indicated that, in both mountain and coastal areas, to a similar extent, tourist enterprises decide to operate either year-round or seasonal [

19]. Making decisions to limit or maintain activities during the year is dependent not only on economic factors but also on the consideration of non-economic factors [

19].

From the enterprises’ point of view, the seasonality of tourism demand always complicates economic activity. It causes periods of limitation or shutdown in their functioning, makes it difficult to maintain constant contact with tourists, employees, and suppliers, causes insufficient use of facilities for most of the year, and disrupts the financial economy [

16]. Nevertheless, seasonality is not viewed as an urgent problem by many tourism enterprises [

3,

20]. Getz and Nilsson (2004) examined the impact of the seasonality of tourism demand on the functioning and organization of family businesses in the tourism industry in Bornholm, Denmark. Family tourism enterprises support seasonality, because periods of income growth ensure financial stability, and they use rest periods to relax and balance family life [

21].

Seasonality in tourist areas significantly affects the condition of the labor markets and local entrepreneurship. It leads to both widespread seasonal employment and unemployment, the periodic opening and closure of enterprises serving tourists, and the keeping of jobs in enterprises. Planning employment in the tourism sector requires considering seasonality and a different approach than in other industries to estimate the costs of recruiting, training, retaining, and firing employees. Running a business in the tourism industry is related to the adoption of an appropriate approach to determining the demand for labor by enterprises.

Enterprises operating only in seasonal terms employ workers merely during the tourist season to carry out specific, mostly simple jobs. Their salary is treated as a variable, closely related to seasonal changes in tourist demand. Currently, seasonal workers in these enterprises are mainly young people who are not looking for permanent employment. In their case, seasonal employment is related to the form of spending free time during the break between classes [

22,

23], therefore their salary is not a key issue in this case and may be lower. On the other hand, enterprises operating all year round employ and retain their employees also after the tourist season, i.e., when operating revenues do not cover the costs of their salary. Enterprises then accept the occurrence of periodic inefficiencies and a different degree of work utilization throughout the year. These employees are treated as capital that is kept in storage at times of reduced demand. The salary of year-round employees is treated as quasi-permanent in these enterprises.

Previous studies on the impact of the seasonality of tourism demand on the choice of employment policy in the tourism industry indicate that employment decisions in tourist enterprises are conditioned by the seasonality of tourism demand. From the point of view of rationality, an immediate adjustment of employment to changes in the size of tourism demand would be the most effective. However, such an approach is not always possible, e.g., due to the limited availability of candidates for seasonal work. Assessing the rationality of employment decisions in the tourism industry requires understanding the conditions of the functioning of enterprises operating in high seasonality and the realities of local labor markets.

The research presented in the article identifies the applied practices of determining the demand for labor in tourism industry enterprises and their determinants. The aim of the study is to determine how tourist enterprises define the demand for labor and what they motivate their employment decisions with. The main research question concerns what prompts tourist enterprises to choose the applied labor demand determination practice and how the opinion on the condition of the local labor market influences this choice. The study identified methods of determining the demand for seasonal and all-year workers. The analysis was based on theoretical models of labor demand. It was assumed that in the tourism industry, seasonal fluctuations can be treated in the same way cyclical fluctuations are treated in the analyses of dynamic labor demand. The results of the survey conducted in the tourism industry enterprises in the seaside region in Poland provided valuable information, in particular in the field of the applied rules of employing seasonal and year-round workers in the tourism industry. The study itself aims to fill a gap in understanding labor demand determination practices in the tourism sector, which is essential for tourism businesses, tourism organizations, and local authorities alike.

The article is divided into three main sections. The first part identifies the characteristics of employment in tourism, i.e., the industry exposed to large seasonal fluctuations in demand. The discussion was based on the assumptions of the labor demand theory. The second section characterizes the sources of information and the research method that was used to assess the impact of seasonality on the selection of practices for determining the labor demand in enterprises operating in the seaside area of Poland. The section describes the questionnaire, data collection procedure, and data analysis procedures. The last part presents and discusses the results of the study and formulates conclusions from the analysis.

2. The Specificity of Employment in Tourism

The most important feature characterizing the activity of tourist enterprises is the seasonality of tourism demand, which occurs in all regions of the world [

3,

8,

20,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28] and concerns various types of tourism [

29,

30,

31]. Seasonality is the regular occurrence of changes in the volume of demand for tourist goods and services throughout the year (In theory, seasonal fluctuations are defined as changes in the time series repeated in certain seasons, or the systematic, though not necessarily exactly regular, movements of a certain size during the year [

32], caused by weather and economic changes and the distribution of religious holidays. The definition of seasonality emphasizes the types of causes of this phenomenon, the annual period of fluctuation, and the relative regularity of its occurrence [

33]). The phenomenon in the tourism market is permanent and has a negative impact on the functioning of tourist enterprises. Enterprises do not fully use the resources that they have at their disposal in the off-season and are unable to meet all the significantly overwhelming demand for tourist goods and services during the season. In a situation of a decrease in demand (after the tourist season), there are or could be goods and services on the market that do not find buyers. On the other hand, in the situation of an increase in seasonal demand in the tourism market, there is a shortage of supply of tourist goods and services, which results in the inability to fully satisfy the emerging demand. In each of these situations, tourist enterprises lose. In the first case, the loss relates to lost revenues related to unused capacity. However, in the second case, it is lost income related to the inability to meet the existing tourism demand. From the point of view of the functioning of tourist enterprises, the situation is difficult to solve, despite the high predictability of changes in tourism demand.

The high seasonality of tourism demand is also a difficult situation for the human resources departments in enterprises. Tourism demand generates labor demand in the tourist season and its total or significantly reduced level in the off-season. The labor demand in tourist enterprises considers the seasonal nature of the demand for tourist goods and services—enterprises regularly experience periods of additional recruitment and layoffs, mainly of seasonal workers.

The general definition of labor demand relates to companies’ decisions about employing, training, and dismissing employees—it comes down to answering the questions of how many employees to employ and how many working hours they should work [

34]. It indicates the total number of employees or working hours that have been filled and the existing demand for employees, i.e., job vacancies [

35]. This decision results directly from the demand for goods and services, i.e., the interaction between the volume of labor demand and the market for goods and services, and the interaction with other production factors [

36,

37]. In a short period, the labor demand illustrates changes in employment and wages, which are the result of changes taking place in the market of goods and services—an important element of this mechanism is the production structure, which, together with the organization of work and technology, determines the level of employment and the number of hours needed. In the long term, the enterprise maximizes its profit when the marginal productivity of the factors of production equals their price, i.e., the marginal productivity of labor equals the wage rate, and the marginal productivity of capital equals the rate of return [

38]. There are two main approaches to determining labor demand in labor demand theory: Static and dynamic [

34,

38].

The basic assumption of the static approach is the smoothness of matching changes in the volume of labor demand to the production volume, assuming that the change in employment does not generate additional costs in enterprises [

34,

39]. The demand for labor describes the quantitative relationship between the level of the labor resource and the volume of production at fixed wages, and at the same time determines the flexibility of substitution between inputs. The use of a statistical approach to estimate the size of employment is useful, but has certain limitations—the most important is ignoring the problem of a partial mismatch between the workforce and the size of production. This problem is solved by the dynamic theory of labor demand.

In the theory of dynamic labor demand, when determining the size of employment, partial mismatches of the labor resource to changes in the size of production are introduced. Thus, the labor demand function determines the level of employment, considering the costs of adjusting the labor demand and its variability to production fluctuations. The costs of matching the labor demand include the costs of job creation, their dismantling, and on-the-job training (formal and informal). Moreover, the loss of labor productivity caused by employing workers with lower qualifications and their incomplete involvement in work may also be a cost for the enterprise. Often, enterprises decide to incur additional costs of maintaining employees during an economic downturn, and in these enterprises, there is labor underutilization and labor hoarding.

Labor hoarding refers to companies’ employment decisions during periods of decline in economic activity [

34,

37,

38,

39]. It is based on the immediate adjustment of employment to changes in the volume of production. Enterprises, when deciding to hoard work, analyze the costs of employment, training, and dismissal of employees as a constant component of costs in a short period. If in the conditions of cyclical decline in production, the costs of dismissals, re-employment, and training exceed the costs of employees’ salaries, then enterprises decide to keep employees [

34,

37,

39]. This decision results from comparing the level of risk related to the dismissal of trained workers in conditions of short-term decline in production with the risk of their unavailability when production starts to increase. Hence, there is a need to perceive employment costs as a fixed factor of production in the short term, at least in relation to selected groups of employees. Labor hoarding may be a practice used more willingly in enterprises when there is a shortage of employees on the labor market, e.g., in a situation where the availability of employees with the desired, unique qualifications is limited [

40]. When enterprises predict only a temporary reduction in the demand for goods and services, they are also more likely to decide to keep working [

41]. Companies in a relatively good financial situation decide to store work [

42,

43].

In the context of the considerations of the labor demand in the tourism industry, an interesting question seems to be whether fluctuations in demand for seasonal goods and services require separate treatment or whether they can be treated in an analogous way to the analyses of dynamic labor demand—the way cyclical fluctuations are treated. An additional motivation for the analysis is the difficult situation in local labor markets. The functioning of enterprises in the conditions of constant shortages of employees, a small number of unemployed, and the lack of or little discipline in the workplace forces them to redefine the principles of human resource management, and sometimes, to apply the practice of seasonal labor hoarding.

3. Materials and Methods

The aim of the study is to determine how tourist enterprises define the labor demand and what motivates their employment decisions. The main research question concerns the identification of the employment practice and how the condition of the local labor market influences this choice.

The following research hypotheses were verified:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Employment practice in tourism industry enterprises divides them into those that hoard labor and not hoard labor.

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Tourist enterprises that hoard labor and do not hoard labor have the same opinions on the availability of seasonal and year-round job candidates in the local labor market.

Hypothesis 3 (H3). Tourist enterprises that hoard labor and do not hoard labor have the same opinions on the availability of seasonal and year-round workers and their preferences in terms of the level of salary and working time.

Hypothesis 4 (H4). Tourism enterprises that hoard labor and do not hoard labor have the same opinions on the productivity of seasonal and year-round workers.

The basis for the inference was the analysis of the results of the survey, which provided information on the applied practices of employing employees and the opinions of tourist enterprises on the features of the local labor market in the Baltic Sea area.

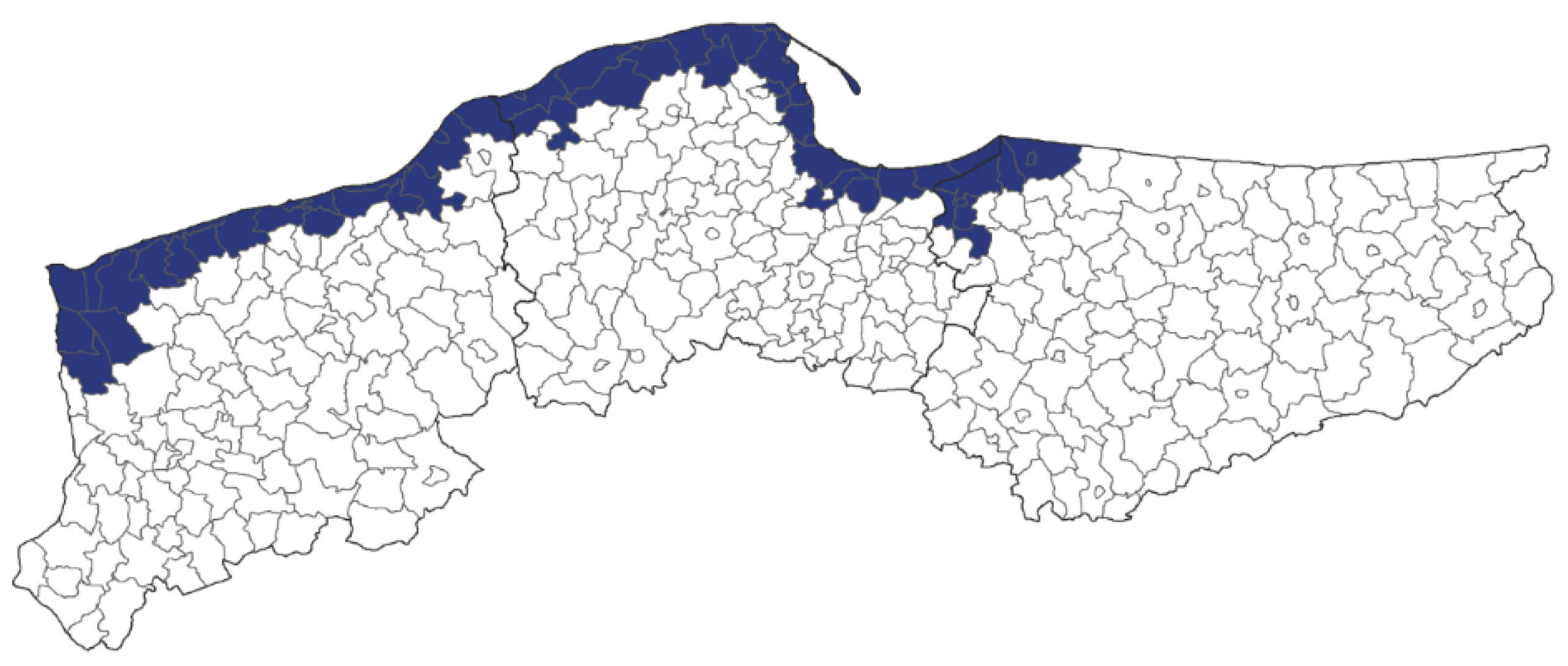

A survey of tourism industry enterprises was conducted in Poland in an area classified as a seaside area [

44], which included 55 communes. The area of communes covered by the study is presented in

Figure 1.

This area is located on the Baltic Sea or in its immediate vicinity. The region of coastal communes is essentially a peripheral area of a tourist nature with a network of small towns and villages—the exception is the Gdańsk–Gdynia–Sopot metropolitan area. Due to the type of tourist attraction and the climatic conditions of the Baltic Sea, this area is characterized by large seasonal fluctuations in tourist demand with one significant tourist season in July–August [

11].

Enterprises in the tourism industry were considered enterprises whose predominant activity was related to accommodation or catering services by the Polish Classification of Activities—PKD 2007 [

45].

During the study, a questionnaire was used, which consisted of three parts and general information. In the first part, the opinions of enterprises on the local economy and labor market, as well as the attitudes of job candidates and employee groups, i.e., seasonal workers and year-round workers, were obtained. The second part of the questionnaire concerned the description of the general conditions for making decisions concerning the reporting of the labor demand by tourist enterprises. In the third section, enterprises defined the conditions of employment of seasonal workers. The general information section contained general characteristics of the surveyed enterprises. The metric data made it possible to examine the structure of the sample according to the place and type of business activity, year of commencement of the business activity, achieved financial results, the specificity of the seasonal activity, and the conditions of employing employees, including hiring seasonal workers. The questionnaire has been validated and pre-tested by academics and experts. Both academic and industry experts refined the final version of the questionnaire.

When filling in the questionnaires, enterprises were assured full anonymity, and the possibility of withdrawing from participation in the study was given. The overwhelming majority of responses were qualitative. In most cases, enterprises were asked to choose one of the answers provided. In selected questions, the scaling of answers with a 5-point Likert scale was used.

The survey was conducted in September–November 2019, i.e., the last tourist season before the pandemic, using the CATI (computer-assisted telephone interview) method. The respondents were people representing tourist enterprises who knew the level of demand for labor reported by the enterprise and its conditions.

In the analysis of the results of the survey, the methods of statistical inference analysis were used. As the set of enterprises turned out to be heterogeneous in their approach to determining labor demand, they included enterprises belonging to two separate subsets, i.e., enterprises that hoard labor and do not hoard labor. Therefore, the set of responses was analyzed with the significance of the differences test. Considering the nature of the comparative groups, the number of comparative groups, and the measurement scale of the dependent variable, the Chi-square test was used to verify the statistical hypotheses.

In total, 360 enterprises from the tourism industry, which conducted activities related to accommodation or catering services in the area of coastal communes, participated in the study. Before starting the analysis, the questionnaires were checked for completeness of information important from the point of view of their usefulness in determining the mechanism of reporting the labor demand—all 360 questionnaires turned out to be useful.

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the surveyed group of enterprises.

All the surveyed enterprises were enterprises that conducted activities related to accommodation and catering services. In total, 60.8% of the surveyed sample of tourist enterprises are enterprises whose predominant activity concerned accommodation related to, inter alia, hotels and similar accommodation, lodging and short-stay accommodation, camping sites, and campsites. The remaining part—39.2%—was constituted by enterprises conducting gastronomic activity, i.e., restaurants and other permanent gastronomic establishments, mobile gastronomic establishments, catering, and other gastronomic services. The spatial distribution of enterprises participating in the survey was consistent with the adopted research area. The largest area of coastal communes was constituted by the communes of the West Pomerania province and the smallest of the Warmia-Masuria province. Hence, 49.4% of the surveyed enterprises were enterprises whose place of business activity was in the communes of the West Pomerania province. A similar percentage of enterprises—47.5%—were enterprises located in the Pomerania province. Only 3.1% of the studied sample are enterprises from the Warmia-Masuria province. This state is related to the geographical location of the municipalities classified as seaside tourist areas. Moreover, it was observed that 66.4% of all surveyed entities were micro-enterprises, i.e., enterprises employing up to 9 people. Small enterprises, employing from 10 to 49 people, accounted for 29.7% of the surveyed sample. Furthermore, 2.5% and 1.4% of enterprises, respectively, were medium and large enterprises. The structure of enterprises according to the size measured by the number of employees is consistent with the trends observed in the tourism sector of the seaside area in Poland. Small enterprises—the sector of micro and small enterprises—dominate in the coastal tourist areas. When analyzing the financial situation of tourist enterprises, it was observed that 81.6% of enterprises replied to the financial result, including 64.7% who declared a positive financial result, 11.1% who declared zero, and 5.8% who declared a gross loss. A significant percentage of enterprises, 18.3%, refused to provide an answer about their financial situation. Moreover, 60.3% of the surveyed enterprises were enterprises that declared running year-round activity, while 38.5% indicated seasonal activity and 1.1% refused to answer this question. Questionnaires from companies that refused to reply were analyzed in terms of their suitability. The analysis of the replies to the remaining questions they gave resulted in the decision to leave these questionnaires in the dataset. Enterprises running seasonal and year-round operations mostly indicated seasonal increases in sales in the months of the summer season, i.e., July and August.

4. Results

The opinion of the tourist enterprises regarding the increase in revenues in the tourist season and its impact on the seasonal demand for employees was the basis for determining the employment practice. In total, 68.1% of enterprises conducting tourist activity declared employing seasonal workers, including 24.4% of enterprises employing only seasonal workers and 43.6% of enterprises employing both seasonal workers and year-round workers. Furthermore, 31.9% of enterprises indicated that, during the analysis period, they employed only full-year employees, despite the observed increase in revenues in selected months of the year.

Treating seasonal fluctuations in the same way cyclical fluctuations are treated in the analysis of dynamic labor demand and the analysis of answers to the question regarding the type of employment forms used (seasonal, seasonally year-round, all-year-round employment) allowed for the classification of enterprises into two groups: (i) The group of enterprises hoarding labor (272 enterprises—75.6%) and (ii) enterprises that do not use the practice of labor hoarding (88 enterprises—24.4%).

Tourist enterprises that used labor hoarding in their activities used it in two different ways, i.e., they applied (i) a complete labor hoarding strategy or (ii) a selective labor hoarding strategy. Complete labor hoarding applied to enterprises that, despite the significant seasonality of tourism demand, demanded only year-round workers. On the other hand, selective labor hoarding concerned the simultaneous employment of year-round workers and, in periods of increased tourist demand, also seasonal workers. Businesses that do not use labor hoarding are those that only employ seasonal workers. These enterprises reacted immediately to the seasonal change in tourism demand. They reported the demand for labor only during the tourist season. The above-discussed approaches of enterprises in the tourism industry of coastal regions in Poland are presented in

Figure 2.

The presented results allow for positive verification of Hypothesis 1: Employment practice in tourism industry enterprises divides them into those that hoard labor and do not use the practice of labor hoarding. The labor demand and the decision to hoard or not hoard workers are related to the characteristics of the enterprises. Moreover, it has been observed that tourism enterprises have the skills to accurately predict tourism demand and its seasonal and cyclical increases. The considerable regularity of changes allows for assuming that tourist enterprises make decisions regarding seasonal employment simply and flexibly. However, in the conditions of labor market shortages, an important issue in adjusting employment to seasonal changes in tourism demand is estimating the costs of the recruitment, training, payment, and dismissal processes. Knowledge of the specificity of the functioning of the local labor market and economy, i.e., knowledge of the availability of a workforce with appropriate characteristics, facilitates the identification of these costs and prompts tourist enterprises to adopt one of two approaches to employment practice.

The study assumed that the practice of employing workers in tourist enterprises depends on the opinions of enterprises on the features of the local labor market, i.e., (i) the availability of job candidates, (ii) opinions on the characteristics of seasonal and year-round workers, particularly the acceptance of the level of wages and extended working time during the season, and (iii) opinions on the difference in labor productivity of seasonal and year-round employees between groups of enterprises.

As shown by the results presented in

Table 2, there is a statistically significant difference in probability between the enterprises hoarding labor and those not using labor hoarding in the perception of the candidates’ willingness to undertake seasonal or permanent work in the coastal region. Enterprises that use labor hoarding indicated that there are applicants for year-round work available on the local labor market. On the other hand, in enterprises that did not use labor hoarding, there was a belief that seasonal workers were more accessible. A significant part of tourist enterprises did not have an opinion on the availability of job candidates and their preferences as to the durability of employment, while 20.6% of enterprises hoarded labor as compared to 23.9% of those who did not hoard workers.

The responses of tourist enterprises with labor-hoarding practices also significantly differed from the responses of enterprises that do not hoard labor in terms of opinions on the tendency of seasonal and year-round workers to accept the average wage and working time in tourism (

Table 3 and

Table 4). In the opinion of enterprises that hoard labor, year-round employees were more likely to accept a salary at the level of the average wage in the tourism sector or lower—41.2% of these enterprises, compared to the indications of 15.9% of enterprises that did not use labor-hoarding practices. On the other hand, 19.5% of enterprises that hoard labor, compared to 40.9% of enterprises that do not use labor hoarding, thought that the group of seasonal workers is more willing to accept lower wages than those applicable to the industry. As in the case of the opinion on the availability of job candidates in the local labor market, a significant number of enterprises, i.e., 18.0% of enterprises with labor-hoarding practices and 28.4% of those who do not use labor hoarding, did not have an opinion on the willingness of employees to accept the average wage in the tourism industry or lower.

In the opinion of enterprises that hoard labor, year-round workers (23.2% of responses) were more likely to accept a working time of more than 8 h during the tourist season, compared to 1.1% of responses of enterprises that do not use labor hoarding. At the same time, they indicated (32.7% of enterprises with labor-hoarding practices) that, during the tourist season, seasonal workers would be more willing to give such consent. The same opinion was expressed by tourist enterprises not hoarding labor—44.4% of enterprises not hoarding labor expressed the opinion that seasonal workers are more likely to accept extended working hours in the tourist season. As many as 27.2% of enterprises that hoard labor and 51.1% of those who do not hoard labor did not have an opinion about the tendency of employee groups to accept extended working hours during the tourist season.

In the last step of the analysis, similar opinions of tourist enterprises about the work productivity of seasonal and year-round workers were examined. The opinions of enterprises using labor hoarding and not using labor hoarding on the work productivity of employee groups differed significantly, which was presented in

Table 5. The enterprises that used labor hoarding assessed the productivity of work of year-round workers as higher. In the opinion of labor-hoarding enterprises, year-round workers compared to seasonal workers were characterized by higher labor productivity (41.2% of enterprises expressed such an opinion, compared to 5.7% of indications by the group of enterprises not hoarding labor). On the other hand, the perception of labor productivity of seasonal workers as being higher than that of year-round workers was higher among enterprises that did not hoard labor. In fact, 34.1% of enterprises not hoarding labor believed that seasonal workers were characterized by higher labor productivity than year-round workers, and 9.6% of enterprises that hoard labor believed that seasonal workers were characterized by higher labor productivity. As in the case of the opinion on the availability of job candidates in the local labor market, the level of salary, and extending the working time of employees during the tourist season, a significant number of enterprises did not have an opinion on the labor productivity of seasonal and year-round workers. As many as 24.2% of labor-hoarding enterprises and 53.4% of those who do not hoard labor did not have an opinion about the productivity of the analyzed employee groups.

The analysis of enterprises’ responses allows for the rejection of hypotheses 2 to 5 entirely. The responses of enterprises that apply the practice of labor hoarding significantly differ from the responses of enterprises that do not apply the practice of labor hoarding in terms of opinions on the availability of seasonal and year-round jobs candidates, employees’ preferences in terms of the level of wage and working time, and their labor productivity.

Enterprises using the practice of labor hoarding indicated that the job candidates available on the labor market are more likely to be employed for a year-round job (38.6% of responses), while enterprises that do not use labor-hoarding practices indicate that candidates available on the local labor market are more likely to be employed for seasonal jobs (46.6%).

Tourist enterprises using labor-hoarding practices indicated that year-round workers are more likely to accept wages at the level of the average wage in the industry or lower (41.2%), while enterprises that do not use labor-hoarding practices indicate seasonal workers to be more likely to accept wages at the level of the average wage or below in the tourism sector are (40.9%). The hypothesis referring to the same opinions on preferences in terms of working time among tourism industry enterprises that do and do not keep jobs was rejected, even though both enterprises using the practice of labor hoarding and enterprises not using the practice of labor hoarding indicated that seasonal workers are more inclined to work longer than 8 h a day in the tourist season (32.7% of responses vs. 44.4% of responses).

Enterprises in the tourism industry that hoard and do not hoard labor have significantly different opinions on the labor productivity of seasonal workers and the labor productivity of year-round workers. Enterprises using the practice of labor hoarding indicated that year-round employees achieve higher labor productivity (41.2% of responses), while enterprises that do not use labor-hoarding practices indicate that seasonal workers achieve higher labor productivity (34.1%).

5. Discussion

The seasonality of tourism demand is a ubiquitous feature of the tourism industry that affects the degree of labor utilization throughout the year. Material, financial, and human resources are used by some tourist enterprises for only a dozen or so weeks a year. Actions aimed at extending the tourist season and limiting the seasonality in tourism have not brought satisfactory results so far.

Thus, the seasonality of tourism demand is a natural condition for the functioning of tourist enterprises and affects the choice of employment practice. There are enterprises operating all year round and enterprises operating only in the tourist season. Regardless of the adopted business model, work in the tourism sector is seasonal. It is observed that tourist enterprises seasonally increase either (i) the number of working hours employed, (ii) the number of employees, (iii) or both of these categories simultaneously. Enterprises meet the increased seasonal tourism demand by engaging additional working hours of employees all year round and/or by employing seasonal workers. In the first case, enterprises employ only year-round workers, treating them as capital that is hoarded during the low season. They organize their work during the year in such a way as to meet the increased tourism demand in the high season, and in the low season, they accept their incomplete use. The second, extremely different, employment practice represents the traditional approach to determining the labor demand. In response to changes in demand for goods and services, enterprises immediately hire and fire workers—they use the practice of employing seasonal workers. In the tourism industry, there is also a third approach to the practice of employment, as there are enterprises in which the employment structure, during a periodic increase in tourism demand, consists of both year-round workers and seasonal workers. These companies adopt a selective approach to labor-hoarding practices.

The identification of employment practices allows us to assume that companies in the tourism industry treat seasonal fluctuations in determining the employment practice in the same way cyclical fluctuations are treated in the analyses of labor demand. Enterprises considering the possibilities of increasing employment in the tourist season are guided by the principle of profit maximization. They compare the cost of maintaining year-round workers with the costs of the hiring, training, salary, and dismissal of seasonal workers. When the costs of maintaining employees throughout the year are lower than the costs related to employing employees in periods of seasonal increases, then enterprises decide to hire full or partial employees all year round. Otherwise, enterprises flexibly adjust the size of employment to changes in the volume of tourism demand—they do not decide to employ year-round employees. This approach to employment practice refers to the theory of dynamic demand for labor, in which enterprises, when determining the amount of labor demand, consider the costs of recruitment, training, and dismissal as a constant component of costs in a short period.

The analyses aimed to understand how tourist enterprises determine the labor demand and what motivates their decisions. The results of the analysis carried out in the tourist region of the Polish Baltic Sea showed that 75.6% of tourist enterprises use the practices of complete or selective labor hoarding. These enterprises employ year-round workers, complementing the tourist season by adjusting their working hours for year-round workers and/or employing additional seasonal workers to perform additional seasonal work. In total, 24.4% of enterprises immediately adjusted their employment to seasonal changes in demand. Reductions in tourism demand resulted in a reduction in the working hours of seasonal workers or a complete reduction in seasonal employment.

Moreover, we analyzed the impact of the opinions of tourist enterprises about the features of the local labor market on the practices of labor hoarding or not labor hoarding (This was defined by the opinion of tourism enterprises on the tendency of job candidates for year-round and seasonal work, the tendency of year-round and seasonal workers to accept an average salary in the tourism industry or lower, and the tendency of year-round and seasonal workers to extend the working time in the tourist season by more than 8 h, as well as the opinions on work productivity of year-round and seasonal workers). It was shown that opinions on the tendency of job candidates to accept year-round and seasonal work, the tendency of year-round and seasonal workers to accept wages at the average level in the tourism industry or lower and extended working hours in the tourist season, and opinions on the productivity of year-round and seasonal workers are significantly different.

Tourism enterprises that practice labor hoarding thought that:

- -

More often in the local labor market, one can meet candidates willing to be hired for a year-round job.

- -

Full-year workers are more likely to accept a salary at the level of the average salary in the tourism industry or lower.

- -

Year-round employees are characterized by higher labor productivity.

Tourist enterprises that do not apply the practice of labor hoarding expressed the opinion that:

- -

More often in the local labor market, one can meet job candidates willing to be hired for seasonal work.

- -

Seasonal workers are more likely to accept a salary at the level of the average salary in the tourism industry or lower.

- -

Seasonal workers are characterized by higher labor productivity.

Only in the case of the opinion on the willingness to accept an increased workday exceeding 8 h in the tourist season were both enterprises using the practice of labor hoarding and those not applying labor-hoarding practices consistent that seasonal workers are more likely to accept a more than 8-h working day in the season. The analysis of the remaining answers to this question led us to finally decided to reject the hypothesis regarding enterprises that hoard and do not hoard labor having the same opinions about the preferences of seasonal and year-round workers in terms of the level of working time.

The results of the study presented in the article propose the identification of employment practices in tourism industry enterprises. They identify employment practices depending on the speed of adjusting the size of employment to changes in tourism demand volume, assuming that tourism industry enterprises treat seasonal fluctuations in a similar way to cyclical fluctuations in analyses of dynamic labor demand. A significant number of tourist enterprises treat their employees as capital that is hoarded after the tourist season. The opinion of tourist enterprises on the situation of local labor markets may be a potential motivation to choose the practice of labor hoarding. The presented content is the first major attempt at research carried out by the authors, the aim of which is to understand the determinants of the choice of employment practice in tourist enterprises, i.e., enterprises operating in high seasonality.

One limitation of the analysis is the large number of questions to which tourist enterprises, both those hoarding labor and those not hoarding labor, did not answer, indicating the lack of opinion on the situation of the local labor market. The aim and concept of the research of the presented article did not allow us to present many interesting issues, i.e., the impact of the size of enterprises, the PKD classification, or their financial condition on the choice of employment practice, i.e., the practice of labor hoarding or not using the practice of labor hoarding. The proposed approach should be treated as introductory, introducing a broader study of seasonal determinants of labor demand in the tourism industry, including research on the characteristics of seasonal and year-round workers, i.e., recruitment costs, salary, employment flexibility, working conditions, qualifications, positions, and the type of work performed.