Research on the Cultural Tracing of the Patriarchal Clan System of Traditional Buildings in the Eastern Zhejiang Province, China, Based on Space Syntax: The Case Study of Huzhai in Shaoxing

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

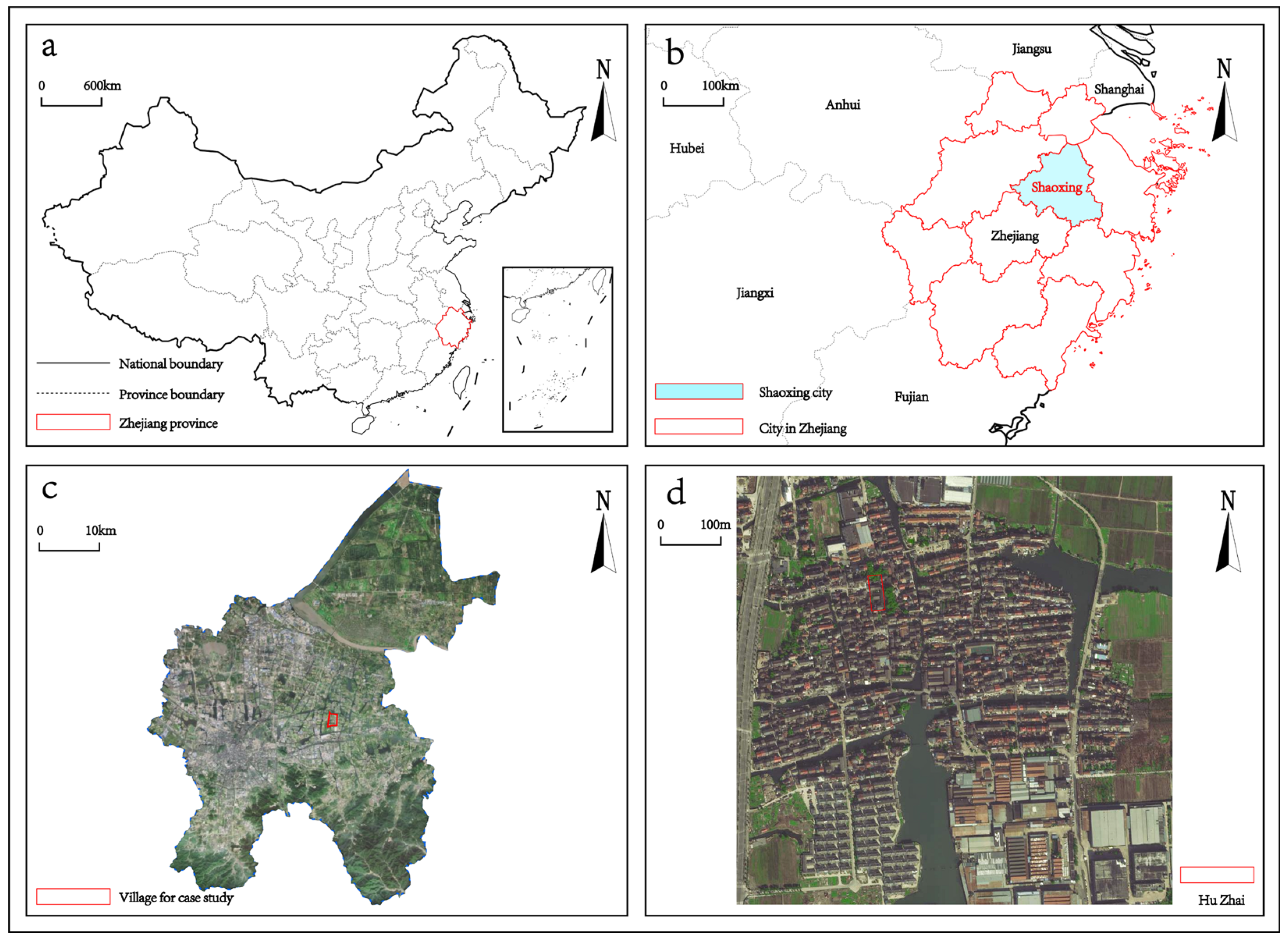

2.1. Sample Selection

2.2. Research Methods

3. Research Process and Findings

3.1. Space Usage Analysis of Huzhai during Daily Activities and Reflected Class Distinctions

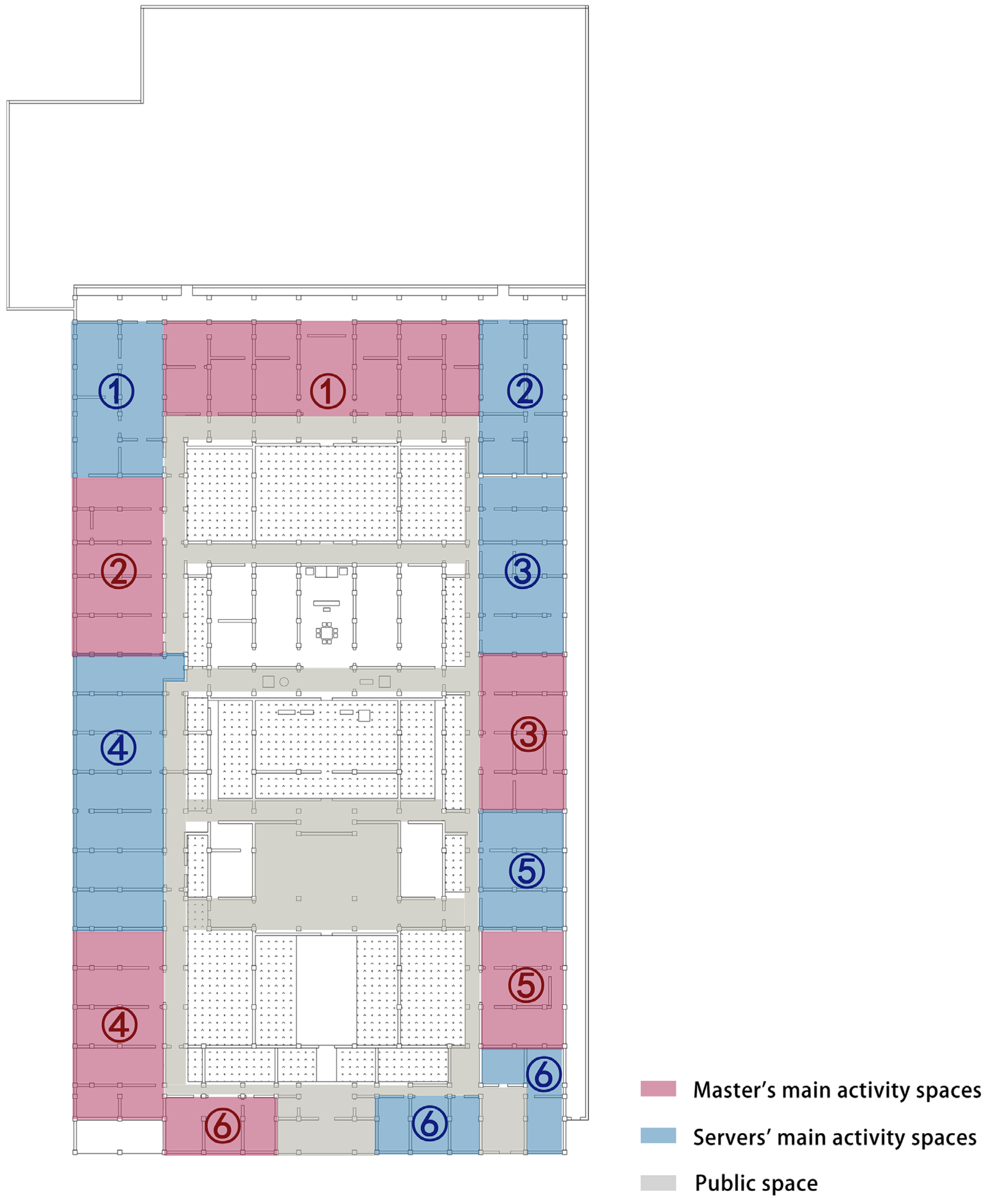

3.1.1. Space Usage Analysis of Huzhai during Daily Activities

3.1.2. Reflection of Class Distinctions in Space Usage of Huzhai during Daily Activities

3.2. Space Usage Analysis of Huzhai under Sacrificial Activities and the Reflected Class Distinctions

3.2.1. Space Usage Analysis of Huzhai under Sacrificial Activities

3.2.2. Reflection of Class Distinctions in the Space Usage of Huzhai during Sacrificial Activities

4. Discussion

4.1. Discussion on Research Methods

4.2. Guidance for the Next Round of Traditional Building Protection and Reuse

4.3. Limitations and Further Research

5. Conclusions

- Spatial organization sequences of traditional buildings have high matching degrees with social hierarchical orders formed by patriarchal culture. Regarding the spatial sequences of the axis symmetry of Huzhai, the corridor space had the highest integration and best accessibility, followed by the public spaces on the central axis, including lobbies, halls, the ancestor’s hall, and the hall of Zuolou. The wing rooms at the two sides and the bedroom spaces had the lowest integration and accessibility. Space division according to superiority, affiliation, and inner–outer relations corresponds to hierarchical family life and family activities under the influence of patriarchal culture. This also reveals the profound influence of the patriarchal clan system on residential buildings in eastern Zhejiang province;

- Space distribution in traditional buildings is determined by the social resource differences of users. Users with different classes, identities, status and wealth have different rights in space control. This is consistent with the results of the space syntax analysis. During the daily activities state, the spaces for the upper class showed a higher overall control value than the spaces for the lower class, reflecting that the upper class had a greater control over the space. During the sacrificial activities, the integration value of the upper class was also significantly higher than that of the lower class, and standing positions of different family members of the upper class also corresponded to different integration values, showing the different control roles over the space depending on the different family members’ statuses. In other words, spatial relationships in traditional buildings comprise the reproduction of user relations in terms of class and social status;

- Except for the spatial layout of buildings, the strict patriarchal clan system is also reflected in the specific detail design of inner spaces. Furniture arrangements in rooms, standing positions, orientations and the line-of-sight direction of people in sacrificial activities are reflected in the integration of the “all lines” analysis. Moreover, the ordered spatial organization and strict furniture arrangements show the strict and ordered hierarchical system in ancient China. These are material reflections of a strict patriarchal system and superiority orders. This research method provides a cultural tracing method for traditional buildings in the future.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zheng, X. The epitome of Chinese traditional culture: After reading Chinese residential architecture. China Book Rev. 2004, 6, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C. On cultural differences in spatial behavior. Archit. J. 1996, 12, 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, W. Arch-patriarch of ancient cultural common sense. Educ. Guide 2021, 37, 36–37. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J. Rites: The ethical intension of Chinese traditional architecture. J. Huaqiao Univ. 2003, 1, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q. Design and Application of Traditional Courtyard Imagery in Contemporary Low-Rise Residential Buildings Case Studies in Yangtze Delta Region; Soochow University: Suzhou, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, J.; Hillier, B. Urban Space 3: Space Syntax and Urban Planning; Southeast University Press: Nanjing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B. Space Is the Machine: A Configurational Theory of Architecture; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B.; Hanson, J. The Social Logic of Space; Cambridge University Press: London, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, P.C. Space syntax analysis of Central Inuit snow houses. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2002, 21, 464–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.-X.; Chiou, S.-C.; Li, W.-Y. Study on courtyard residence and cultural sustainability: Reading chinese traditional siheyuan through space syntax. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krauth, J. Quantifying the Spatial Evolution of Bai People’s Courtyard Houses. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Hangzhou, China, 17–19 July 2021; IOP Publishing: Hangzhou, China, 2021; p. 032009. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Mohannadi, A.; Furlan, R.; Major, M.D. A cultural heritage framework for preserving qatari vernacular domestic architecture. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Mohannadi, A.S.; Furlan, R. The syntax of the Qatari traditional house: Privacy, gender segregation and hospitality constructing Qatar architectural identity. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2022, 21, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alitajer, S.; Nojoumi, G.M. Privacy at home: Analysis of behavioral patterns in the spatial confisuration of traditional and modern houses in the city of Hamedan based on the notion of space syntax. Front. Archit. Res. 2016, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turgut, H.; Şalgamcıoğlu, M. Changing household pattern, the meaning and the use of home: Semantic and syntactic shifts of a century-old house and its journey through generations. In Proceedings of the 12th International Space Syntax Symposium, Beijing, China, 8–13 July 2019; Beijing JiaoTong University: Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, F. The visibility graph: An approach to the analysis of traditional domestic M’zabite spaces. In Proceedings of the Space Syntax: 4th International Symposium, London, UK, 17–19 June 2003; University College London: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Gao, J.; Li, G. Traditional settlement and regional culture of henan province based on space syntax. Econ. Geogr. 2021, 36, 190–195. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, M. Between inside and outside and the spatial pattern: A study on spatial layout of the Wang Mansion in Suzhou based on space syntax. Archit. J. 2020, 6, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, H.; Chen, C.; Xiao, W. Research on the relationship between residential space pattern and traditional culture based on space syntax: Taking Kejia house as an example. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Hangzhou, China, 17–19 July 2021; IOP Publishing: Hangzhou, China, 2021; p. 032059. [Google Scholar]

- Soflaei, F.; Shokouhian, M.; Zhu, W. Socio-environmental sustainability in traditional courtyard houses of Iran and China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 69, 1147–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, J. A comparison analysis of spatial structure of traditional Chinese and Korean residences based on spatial syntax. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 242, 62079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Ma, S. Comparative analysis of habitation behavioral patterns in spatial configuration of traditional houses in Anhui, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang provinces of China. Front. Archit. Res. 2020, 9, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Liu, Y. A comparative study on the spatial characteristics of traditional residential houses in Zhangguying and Laodong Villages based on space syntax. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Hangzhou, China, 17–19 July 2021; IOP Publishing: Hangzhou, China, 2021; p. 032078. [Google Scholar]

- Hillier, B.; Leaman, A.; Stansall, P.; Bedford, M. Space syntax. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 1976, 3, 147–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Xu, K.; Liu, P.; Jiang, R.; Qiu, J.; Ding, K.; Fukuda, H. Space as sociocultural construct: Reinterpreting the traditional residences in jinqu basin, china from the perspective of space syntax. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamu, C.; Van Nes, A.; Garau, C. Bill Hillier’s legacy: Space syntax—A synopsis of basic concepts, measures, and empirical application. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, J. Talk about space syntax again. The Architect 2004, 3, 33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y. The Analysis of Space and Its Configurations Based on Visibility; Southeast University: Nanjing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fouillade-Orsini, H. Belgrade’s urban transformation during the 19th century: A space syntax approach. Geogr. Pannonica 2018, 22, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T. On Application of Space Syntax in Research of Spatial Structure of the Residential Park: Hefei as Example; Anhui Jianzhu University: Hefei, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, R. Research on Traditional Chinese Garden’s Space Syntax and Insights into Contemporary Regional Reconstruction; Tsinghua University: Beijing, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, X.; Lu, Z. Rereading environmental image in terms of spatial syntax. Archit. J. 2014, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, B.; Nasu, S. CCRC common facility spatial structure: A study by space syntax. Asian J. Environ. Behav. Stud. 2017, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, F.; Chen, Y. The study of configuration analysis in art gallery based on space syntax: Comparison of washington national gallery and the shanghai art gallery. In Proceedings of the 2015 4th International Conference on Sustainable Energy and Environmental Engineering, Shenzhen, China, 20–21 December 2015; Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2016; pp. 1165–1171. [Google Scholar]

- Braga, N.; De Saboya, R.T. Analysing the Mutual Influences between Spatial Distribution and Thermal Performance of Tropical Contemporary Brazilian Dwellings. In New Urban Configurations; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 263–271. [Google Scholar]

- Khalesian, M.; Pahlavani, P.; Delavar, M.R. A GIS-based traffic control strategy planning at urban intersections. IJCSNS 2009, 9, 166. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, S.; Liu, J. An comparation study of space character on southern courtyard residence: Based on xiangxi yinzi buildings, huizhou traditional residence, yunnan traditional residence. Chin. Overseas Archit. 2018, 9, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H. Stratum dwelling and the regimen of blood relationship: Analysis of the preliminary characteristics of ancient chinese traditional architecture. J. Southeast Univ. 1998, 28, 97–100. [Google Scholar]

| Corridor | Hall | Bedrooms and Wing Rooms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| corridor 1# | Max: 6.05 | hall 10# | Max: 5.57 | bedroom 13# | Max: 4.48 |

| corridor 2# | Max: 5.70 | hall 11# | Max: 5.66 | bedroom 14# | Max: 5.38 |

| corridor 3# | Max: 5.66 | hall 12# | Max: 4.84 | bedroom 15# | Max: 4.13 |

| corridor 4# | Max: 6.02 | bedroom 16# | Max: 4.33 | ||

| corridor 5# | Max: 6.28 | bedroom 17# | Max: 5.24 | ||

| corridor 6# | Max: 6.50 | bedroom 18# | Max: 5.38 | ||

| corridor 7# | Max: 6.28 | ||||

| corridor 8# | Max: 6.05 | ||||

| corridor 9# | Max: 8.21 | ||||

| Upper Class Maximum Control Value of the Entire Area: 3.75 | Lower Class Maximum Control Value of the Entire Area: 4.51 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Control Value of a Single Corridor | Ratio of to the Maximum Control Value of the Entire Area | Maximum Control Value of a Single Corridor | Ratio of to the Maximum Control Value of the Entire Area |

| corridor 1#: 3.17 | 0.85 | corridor 1#: 3.41 | 0.76 |

| corridor 2#: 2.80 | 0.75 | corridor 2#: 2.58 | 0.57 |

| corridor 3#: 2.56 | 0.68 | corridor 3#: 2.49 | 0.55 |

| corridor 4#: 2.88 | 0.77 | corridor 4#: 2.80 | 0.62 |

| corridor 5#: 3.01 | 0.80 | corridor 5#: 2.89 | 0.64 |

| corridor 6#: 3.28 | 0.87 | corridor 6#: 3.58 | 0.79 |

| corridor 7#: 2.48 | 0.66 | corridor 7#: 2.42 | 0.54 |

| corridor 8#: 2.72 | 0.73 | corridor 8#: 2.75 | 0.61 |

| corridor 9#: 3.75 | 1 | corridor 9#: 4.51 | 1 |

| hall 10#: 2.80 | 0.75 | hall 10#: 2.53 | 0.56 |

| hall 11#: 3.01 | 0.80 | ||

| wing room 12#: 1.85 | 0.49 | wing room 13#: 1.84 | 0.41 |

| wing room 14#: 2.17 | 0.58 | wing room 15#: 2.15 | 0.48 |

| wing room 16#: 2.20 | 0.59 | wing room 17#: 1.57 | 0.35 |

| wing room 18#: 1.85 | 0.49 | wing room 19#: 1.44 | 0.32 |

| No. | Sacrificial Vessels and Furniture | The Purpose of These Vessels and Furniture |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Square table | Placing the ancestral tablets |

| 2 | Chair | The ancestors’ seat, which is required for the ceremony |

| 3 | Incense table | Placing the incense burner and the candlestick |

| 4 | A pot | Sand is placed in a pot, which is then filled with thatch, which is used for sacrifices |

| 5 | Square table | Placing food for the ancestors |

| 6 | Square table | Placing the board or cardboard on which congratulations will be written |

| 7 | The round table | Placing the incense stove, incense spoons, fire bars, soup bottles, etc., on the table. |

| 8 | The wine rack | The place where the wine is displayed |

| 9 | Square table | Placing wine sets, tea sets, vinegar bottles, salt saucers, and so forth. |

| 10 | The rack for a basin | Placing the wash basin and towels |

| 11 | Basin and towels | Washing hands |

| 12 | Square table | Placing the sacrificial items |

| Space No. | “All Lines” Analysis | Convex Space Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| corridor 1# | max: 6.50 average: 4.41 | 1.94 |

| corridor 2# | max: 6.28 average: 4.74 | 1.66 |

| corridor 3# | max: 6.02 average: 4.32 | 1.44 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rao, X.; Zhou, J.; Ding, K.; Wang, J.; Fu, J.; Zhu, Q. Research on the Cultural Tracing of the Patriarchal Clan System of Traditional Buildings in the Eastern Zhejiang Province, China, Based on Space Syntax: The Case Study of Huzhai in Shaoxing. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7247. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127247

Rao X, Zhou J, Ding K, Wang J, Fu J, Zhu Q. Research on the Cultural Tracing of the Patriarchal Clan System of Traditional Buildings in the Eastern Zhejiang Province, China, Based on Space Syntax: The Case Study of Huzhai in Shaoxing. Sustainability. 2022; 14(12):7247. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127247

Chicago/Turabian StyleRao, Xiaoxiao, Junda Zhou, Kangle Ding, Jifeng Wang, Jiaqi Fu, and Qinghong Zhu. 2022. "Research on the Cultural Tracing of the Patriarchal Clan System of Traditional Buildings in the Eastern Zhejiang Province, China, Based on Space Syntax: The Case Study of Huzhai in Shaoxing" Sustainability 14, no. 12: 7247. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127247