On a Comparative Analysis of Individual Customer Purchases on the Internet for Poland, Turkey and the People’s Republic of China at the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Organizational factors—as a method of preventing the spread of the virus: significant restrictions on movement (e.g., lockdown, use of codes (health code, green pass (with GPS) used on smartphones)—allowing entry to public or private institutions, forced and voluntary mass anti-HCV tests covering selected areas or entire countries in some cases, wearing masks in public places, restrictions imposed on the number of people per square meter allowed to enter restaurants, hairdressing salons, etc., restrictions concerning mass events and private meetings) as well as sometimes inconsistent restrictions (e.g., ban on entering the forest or beaches without masks), online education and teleworking),

- Legal: enforced vaccination of all citizens or selected professional groups at one time or at different times, a total or partial ban on leaving home (lockdown), quarantine of varying lengths, lockdowns and closing cities, closing national borders, restrictions on entry to or exit from various countries, ban on travel/entry to a country or selected countries,

- Economic (purchase and distribution of face masks, vaccines, tests, respirators, drugs and their economic consequences),

- Technological—the availability of hardware/devices and software as well as the skills needed to use them, owning devices to make health codes available on-demand in countries where they are required,

- Security—measures applied to secure the growing need for network services and ensure their correct and secure functioning and use,

- Political—the desire to convince the public that the state administration is taking all available steps to prevent and reduce the spread of the pandemic, mitigate its consequences as well as the need to communicate tangible results in this regard.

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Procedure

- Consultancy regarding the research topic and creating the first pilot survey involving broadly defined international comparisons,

- The share of responses to survey questions across countries and the differences between them,

- E-commerce situation before (early 2020) and during (early 2021) the COVID-19 pandemic,

- Traditional electronic commerce (i-commerce) with mobile electronic commerce (m-commerce),

- Selecting research sample groups at each of the cooperating universities,

- Conducting research (Computer-Assisted Web Interviewing method, CAWI) on a verified and tested questionnaire, hosted on the servers of the University of Warsaw,

- Analysis and discussion of the obtained results,

- Drawing conclusions from the study in all mentioned aspects based on the previous analysis and discussion,

- Description of the limitations and establishing directions for future research.

- Infrastructure information,

- E-commerce operations carried out using mobile and desktop devices,

- Sectors and functions of i-commerce and m-commerce tools used, before and during a pandemic,

- Delivery of services and goods as part of e-commerce transactions, and

- Other e-commerce related information during the pandemic.

3.2. Description of the Research Sample

4. Analysis of Results

4.1. Infrastructure Information

4.2. E-Commerce Transactions on Mobile and Desktop Devices

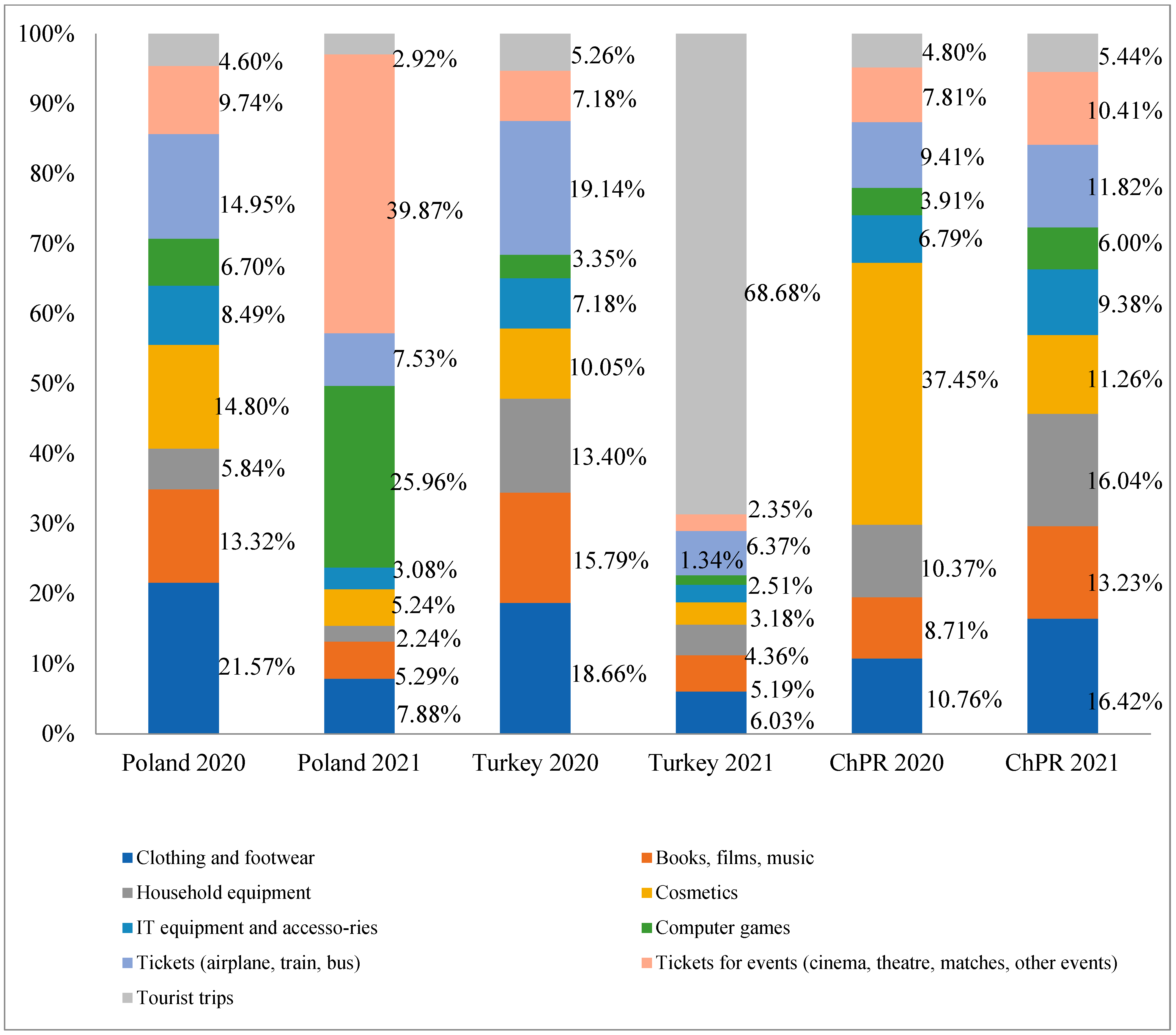

4.3. Sectors and Functions That Used I-Commerce and M-Commerce Tools before and during a Pandemic

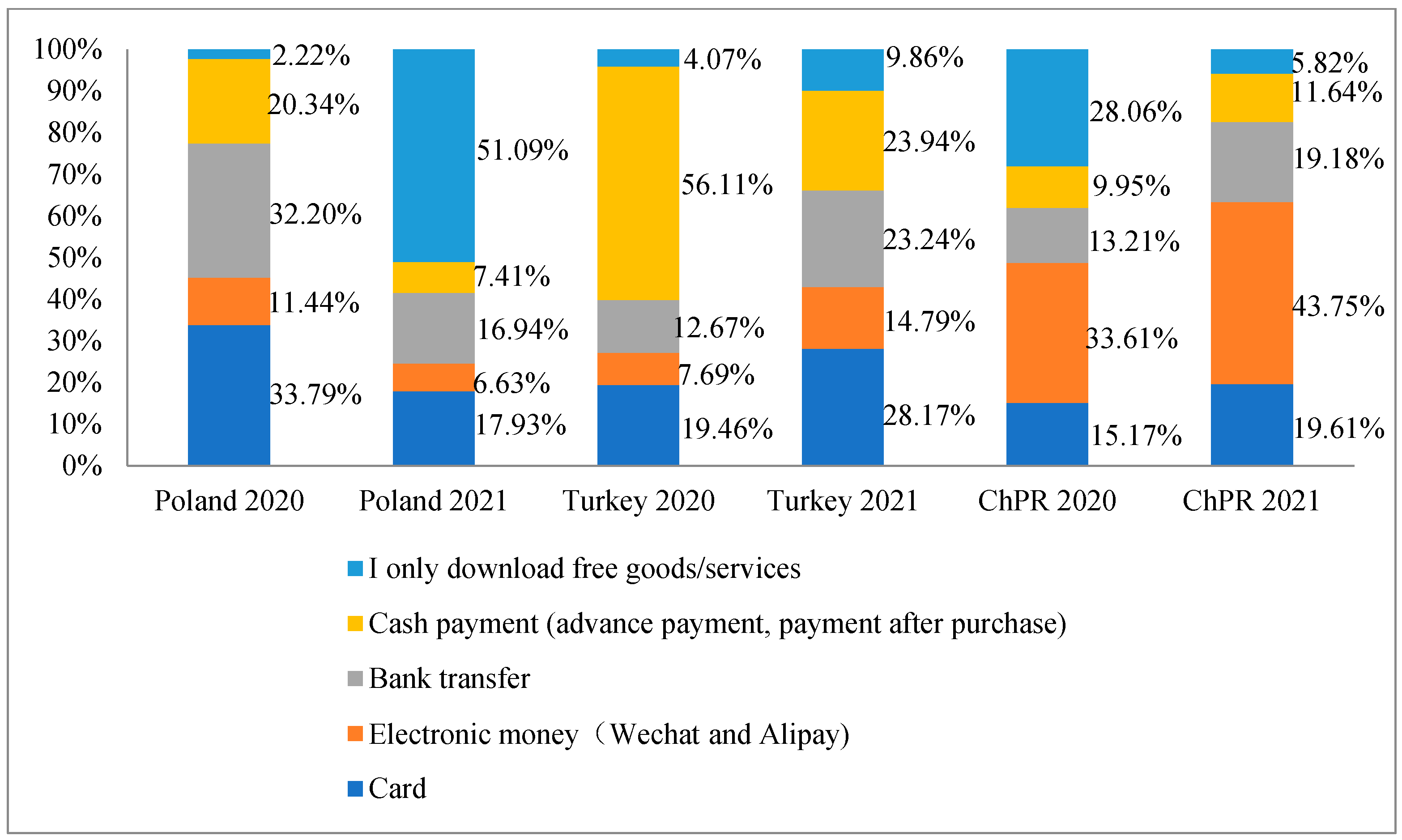

4.4. Methods of Payment and Delivery Regarding E-Commerce Products/Services

4.5. Other E-Commerce-Related Information during the Pandemic Period

5. Discussion of Results

- Mobile purchases of specific products/services during the pandemic,

- The type of devices used to shop online (traditional (online)/mobile/both),

- The type of payment used on mobile devices during the pandemic.

- The type of device used to shop online (traditional (online)/mobile/both),

- Mobile purchases of specific products/services made during the pandemic,

- The relevance of the main functions of websites and mobile applications during the pandemic.

- Traditional (online) purchases of specific products/services during the pandemic,

- Specific products/services one did not buy online using traditional e-commerce solutions before the pandemic,

- Specific products/services that one did not buy online using traditional e-commerce solutions during the pandemic.

- The convenience of using mobile versus traditional online devices during the pandemic [40],

- Mobile purchases of specific products/services during the pandemic,

- Mobile purchases of specific products/services that the respondents would not buy before the pandemic.

- Traditional online purchases of specific products/services prior to the pandemic,

- Specific products/services that the respondents would not buy online (traditionally) during the pandemic [41],

- The primary device used to access the Internet.

- E-commerce transactions are carried out using both traditional (PC, desktop computer) and mobile (smartphone, tablet) devices, depending on the product/service. There is also a tendency to reduce the role of both desktop computers and tablets. Such a trend is mainly visible in Poland, which is also shown by statistical data [11,21,22,28],

- An intermediate solution, where for economic reasons and situational necessity (COVID-19 pandemic), consumer trends are shaped similarly to the Chinese model of consumer behavior on the Internet, simultaneously, the solutions are adapted to the previously applied (in relation to the time before the pandemic) ways of using e-commerce—such a situation can be observed in Turkey [43,44].

- Centralized, accessible to all, highly developed electronic payment and courier delivery system in the PRC, which was developed even before the pandemic and accelerated and strengthened local m-commerce during the COVID-19 pandemic and renewed the place and role of electronic money in e-commerce during that time [35,36,47],

- Asymmetries in the development of specific industries and their treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic—many small and medium-sized stores were mostly open during the pandemic, limiting e-commerce in this sector [49],

- Organizational differences in restrictions related to the COVID-19 pandemic: duration of lockdowns and social distancing in houses and homes (specific areas), accessibility to stores (number of people, number of people per store area, restrictions or bans to enter branch stores or service establishments, etc.),

- The distinctive nature of the governmental policies and economic strategies of the state administration,

- External conditions (international trade and services) with a variable frequency of formal restrictions [50].

6. Conclusions

- Regarding the differences in e-commerce product/service sales to individual customers in the three countries analyzed before and during the COVID-19 pandemic; and

- Sales on mobile versus desktop devices along with the resulting differences will be described in subsequent articles.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Becker, A.; Tian, Y.; Stewart, C. History of E-Commerce. In Electronic Commerce: Concepts, Methodologies, Tools, and Applications; Information Science Reference: Melbourne, Australia, 2008; Volume 1, pp. 1–8. ISBN 978-1-59904-944-1. [Google Scholar]

- Savrul, M.; Kılıç, C. E-Commerce as an Alternative Strategy in Recovery from the Recession. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 24, 247–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Turban, E.; Pollard, C.; Wood, G. Information Technology for Management: Driving Digital Transformation to Increase Local and Global Performance, Growth and Sustainability, 12th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; ISBN 978-1-119-70290-0. [Google Scholar]

- Laudon, K.; Traver, C. E-Commerce 2020–2021: Business, Technology and Society, Global Edition, 16th ed.; Pearson Education Limited: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, C. Theoretical Foundations of Defining the Participatory, Co-Operative, Sustainable Information Society. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2010, 13, 23–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Edward Freeman, R. Managing for Stakeholders: Trade-Offs or Value Creation. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 96, 7–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Information Technology (IT) Glossary—Essential Information Technology (IT) Terms & Definitions. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/en/information-technology/glossary (accessed on 16 April 2022).

- How COVID-19 Triggered the Digital and e-Commerce Turning Point. Available online: https://unctad.org/news/how-covid-19-triggered-digital-and-e-commerce-turning-point (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, Tourism and Global Change: A Rapid Assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2021, 29, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wong, Y.D.; Qi, G.; Yuen, K.F. Contactless Channel for Shopping and Delivery in the Context of Social Distancing in Response to COVID-19 Pandemic. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2021, 48, 101075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E-Commerce in Europe. Available online: https://www.postnord.se/en/business-solutions/e-commerce/e-commerce-reports/e-commerce-in-europe (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Qian, J.; Parker, S.K. Achieving Effective Remote Working During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Work Design Perspective. Appl. Psychol. 2021, 70, 16–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilty, L.M.; Hercheui, M.D. ICT and Sustainable Development. In Proceedings of the What Kind of Information Society? Governance, Virtuality, Surveillance, Sustainability, Resilience, Brisbane, Australia, 20–23 September 2010; Berleur, J., Hercheui, M.D., Hilty, L.M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; pp. 227–235. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlich, M. COVID-19 Induced Changes in Consumer Behavior. Open J. Bus. Manag. 2021, 9, 2425–2451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Zhang, Z.; Li, W. Information Technology Solutions, Challenges, and Suggestions for Tackling the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 57, 102287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasiuk, W.; Dłużniewska, J. Wpływ pandemii COVID-19 na rozwój sektora e-commerce w Polsce. Akad. Zarządzania 2021, 5, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Chmielarz, W.; Parys, T.; Szumski, O.; Zborowski, M. The Impact of the Pandemic (COVID-19) on Globalization—The Perspective of Electronic Commerce. Probl. Zarządzania Manag. Issues 2021, 19, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsari, S.; Sari, D.P. Consumer Factors in Deciding to Purchase Online at Shopee E-Commerce During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Proc. Int. Semin. Islamic Stud. 2022, 3, 174–182. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G. The Impact of COVID-19 on China’s E-Commerce. In Proceedings of the IC4E 2021: 2021 12th International Conference on E-Education, E-Business, E-Management, and E-Learning, Tokyo, Japan, 10–13 January 2021; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 333–336. [Google Scholar]

- Galhotra, B.; Dewan, A. Impact of COVID-19 on Digital Platforms and Change in E-Commerce Shopping Trends. In Proceedings of the 2020 Fourth International Conference on I-SMAC (IoT in Social, Mobile, Analytics and Cloud) (I-SMAC), Palladam, India, 7–9 October 2020; pp. 861–866. [Google Scholar]

- Alcedo, J.; Cavallo, A.; Dwyer, B.; Mishra, P.; Spilimbergo, A. E-Commerce during COVID: Stylized Facts from 47 Economies. Int. Monet. Fund Work. Pap. Res. Dep. 2022, WP/22/19, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier, S. COVID-19: In-Store to e-Commerce Switch by Country 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1105597/coronavirus-e-commerce-usage-frequency-change-by-country-worldwide/ (accessed on 16 April 2022).

- Pantelimon, F.-V.; Georgescu, T.M.; Posedaru, B.-S. The Impact of Mobile E-Commerce on GDP: A Comparative Analysis between Romania and Germany and How COVID-19 Influences the e-Commerce Activity Worldwide. Inform. Econ. 2020, 24, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaunoyer, E.; Dupéré, S.; Guitton, M.J. COVID-19 and Digital Inequalities: Reciprocal Impacts and Mitigation Strategies. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2020, 111, 106424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Hargittai, E.; Marler, W. Digital Inequality in Communication during a Time of Physical Distancing: The Case of COVID-19. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2021, 120, 106717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemba, E. Towards a Sustainable Information Society: People, Business and Public Administration Perspectives; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-83-7875-114-4. [Google Scholar]

- Waizenegger, L.; McKenna, B.; Cai, W.; Bendz, T. An Affordance Perspective of Team Collaboration and Enforced Working from Home during COVID-19. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2020, 29, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirimanne, S.N. COVID-19 and e-Commerce: A Global Review; UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pollák, F.; Konečný, M.; Ščeulovs, D. Innovations in the Management of E-Commerce: Analysis of Customer Interactions during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agus, A.A.; Yudoko, G.; Mulyono, N.; Imaniya, T. E-Commerce Performance, Digital Marketing Capability and Supply Chain Capability within E-Commerce Platform: Longitudinal Study Before and after COVID-19. Int. J. Technol. 2021, 12, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardjono, W.; Selviyanti, E.; Mukhlis, M.; Tohir, M. Global Issues: Utilization of e-Commerce and Increased Use of Mobile Commerce Application as a Result of the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1832, 012024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, M.; Hayakawa, K. Impact of COVID-19 on Trade in Services. Jpn. World Econ. 2022, 62, 101131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodbod, A.; Hommes, C.; Huber, S.J.; Salle, I. The COVID-19 Consumption Game-Changer: Evidence from a Large-Scale Multi-Country Survey. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2021, 140, 103953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, J.; Weekx, S.; Beutels, P.; Verhetsel, A. COVID-19 and Retail: The Catalyst for e-Commerce in Belgium? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 62, 102645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Shi, X.; Guo, H.; Liu, Y. To Buy or Not Buy Food Online: The Impact of the COVID-19 Epidemic on the Adoption of e-Commerce in China. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Liu, Y.; Shi, X.; Chen, K. The Role of E-Commerce in the Urban Food System under COVID-19: Lessons from China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2021, 13, 436–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, P.R.; McMurray, I.; Brownlow, C. SPSS Explained, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; ISBN 978-0-415-27409-8. [Google Scholar]

- Çebi Karaaslan, K. Determinants of Online Shopping Attitudes of Households in Turkey. J. Model. Manag. 2022, 17, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, S.P. The Era of Digital Transformation: Visualizing the Geography of e-Commerce Usage in Turkey. Environ. Plan. A 2021, 53, 1241–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, I.K.; Liu, Y.; Luo, C. Factors Influencing the Continued Acceptance of Wechat Mobile Payments by Chinese Vendors. Inf. Resour. Manag. J. 2021, 34, 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünver, Ş.; Alkan, Ö. Determinants of E-Commerce Use at Different Educational Levels: Empirical Evidence from Turkey e-Commerce Use at Different Educational Levels. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2021, 12, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwald, M. Live Streaming E-Commerce Is the Rage in China. Is the U.S. Next? Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/michellegreenwald/2020/12/10/live-streaming-e-commerce-is-the-rage-in-china-is-the-us-next/ (accessed on 16 April 2022).

- Chmielarz, W.; Zborowski, M.; Fandrejewska, A.; Atasever, M. The Impact of E-Commerce on Globalization Processes: Comparison of Poland and Turkey. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2021, XXIV, 682–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Ma, B.; Zhang, C. Poverty Alleviation through E-Commerce: Village Involvement and Demonstration Policies in Rural China. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 998–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling Ge, Y. Research on the Influence of Mobile E-Commerce Webcast on Users’ Online Shopping Intentions. In Proceedings of the ICEMC ‘21: 2021 the 6th International Conference on E-Business and Mobile Commerce, Seoul, Korea, 27–29 May 2021; pp. 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y. Influence of Cultural Differences on the Establishment of Consumer Trust in a Socialized Cross-Border E-Commerce. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2022, 2022, 9952335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Huang, Y.; Huang, R.; Guojie, X.; Cai, W. Factors Influencing Returning Migrants’ Entrepreneurship Intentions for Rural E-Commerce: An Empirical Investigation in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Zhao, H.; Li, T. The Role of Live-Streaming E-Commerce on Consumers’ Purchasing Intention Regarding Green Agricultural Products. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielarz, W.; Zborowski, M.; Fandrejewska, A.; Atasever, M. Poland–Turkey Comparison of Mobile Payments Quality in Pandemic Time. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2021, 14, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumanska, I.; Hrytsyna, L.; Kharun, O.; Matviiets, O. E-Commerce and m-Commerce as Global Trends of International Trade Caused by the COVID-19 Pandemic. WSEAS Trans. Environ. Dev. 2021, 17, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographics | Poland | Turkey | The PRC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Women | 67.18% | 54.00% | 60.56% |

| Men | 32.82% | 46.00% | 39.44% |

| Age | |||

| >18 | 4.65% | 6.00% | 9.39% |

| 19–24 | 91.99% | 80.00% | 37.09% |

| 25–34 | 3.10% | 14.00% | 31.46% |

| 35–55 | 0.26% | 0.00% | 18.31% |

| 55+ | 0.00% | 0.00% | 3.76% |

| Education | |||

| Bachelor’s degree, undergraduate | 10.59% | 92.00% | 62.44% |

| Primary | 0.78% | 0.00% | 0.47% |

| Secondary | 87.60% | 2.00% | 1.41% |

| Higher | 0.52% | 6.00% | 32.86% |

| Basic vocational | 0.52% | 0.00% | 2.82% |

| Place of origin * | |||

| Large city over 200,000 inhabitants (PRC 20+ million) | 67.18% | 4.00% | 36.15% |

| Large city 51–200 thousand inhabitants (PRC 11–20 million) | 6.20% | 16.00% | 14.55% |

| Medium city 21–50 thousand inhabitants (PRC 6–10 million) | 7.49% | 4.00% | 18.31% |

| Small city up to 20,000 inhabitants (PRC up to 5 million) | 4.65% | 50.00% | 12.21% |

| Village | 14.47% | 26.00% | 18.78% |

| Specialization | |||

| Humanities, including philology, history, cultural studies, art history | 0.52% | 2.00% | 15.02% |

| Medical | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.94% |

| Social sciences, including psychology, sociology, economics, pedagogy, administration, law, management | 77.30% | 30.00% | 48.83% |

| Science, including mathematics, computer science, physics, chemistry | 11.11% | 4.00% | 13.15% |

| Natural sciences, including biology, environmental studies, geography | 0.00% | 0.00% | 2.35% |

| Agricultural, forestry and veterinary | 0.00% | 6.00% | 1.41% |

| Arts, including music, visual arts, theater | 0.00% | 2.00% | 4.69% |

| Technical | 0.00% | 10.00% | 2.82% |

| Other | 28.42% | 46.00% | 11.27% |

| Respondents’ material situation | |||

| Very good (I can afford everything; I can save some money) | 21.71% | 2.00% | 9.86% |

| Good (I am not complaining, but it could be better) | 43.67% | 18.00% | 41.78% |

| Sufficient (I still make ends meet) | 1.03% | 10.00% | 4.69% |

| I am a student; I am not financially independent | 24.81% | 30.00% | 9.39% |

| Average (I have enough to lead a frugal life) | 8.53% | 26.00% | 33.80% |

| Bad (I cannot afford basic goods and services) | 0.26% | 14.00% | 0.47% |

| Professional status | |||

| I am a student | 69.25% | 86.00% | 48.36% |

| I work on a casual basis (contract work/contract of mandate) | 12.14% | 2.00% | 1.41% |

| I work on a full-time or part-time contract | 10.59% | 4.00% | 38.97% |

| Other | 5.68% | 0.00% | 0.47% |

| I am self-employed | 1.81% | 4.00% | 3.76% |

| I am running a household/raising child | 0.00% | 0.00% | 1.41% |

| I am unemployed/currently without a permanent job | 0.26% | 4.00% | 1.88% |

| I am a pensioner | 0.26% | 0.00% | 3.76% |

| No. | Indicator | City Distance | Fisher-Snedecor Inverse Test for Pairwise Comparisons of Individual Countries | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question/Difference between Countries | Poland-Turkey | Poland-PRC | Turkey-PRC | Poland-Turkey | Poland-PRC | Turkey-PRC | |

| 1 | Frequency of Internet use during the pandemic | 49.31% | 67.65% | 73.09% | 1.3996 | 0.6766 | 0.4834 |

| 2 | A basic device used to access the Internet | 79.76% | 55.12% | 32.54% | 2.0404 | 1.7113 | 0.8387 |

| 3 | The impact of the pandemic on the change of the device used to access the Internet | 20.11% | 54.60% | 43.55% | 0.9383 | 1.7877 | 1.9053 |

| 4 | Change in the frequency of use of the device that the respondent uses to access the Internet during the pandemic | 42.48% | 54.73% | 67.29% | 1.4258 | 1.0065 | 0.706 |

| 5 | Frequency of online purchases before the pandemic | 43.70% | 58.85% | 63.77% | 0.4898 | 0.5295 | 1.0809 |

| 6 | Changes in shopping frequency during a pandemic | 37.04% | 29.12% | 33.78% | 1.0735 | 1.1595 | 1.0802 |

| 7 | Type of device used for online shopping (traditional/mobile/both) | 93.24% | 133.07% | 39.83% | 0.8319 | 1.901 | 2.2852 |

| 8 | Changing role of the showroom during a pandemic | 61.37% | 30.16% | 42.37% | 1.3996 | 0.6766 | 0.4834 |

| 9 | Convenience of using mobile devices versus traditional devices during a pandemic | 73.72% | 58.44% | 130.40% | 2.0404 | 1.7113 | 0.8387 |

| 10 | Relevance of the main functions of websites and mobile applications during a pandemic | 28.12% | 110.29% | 82.17% | 0.9383 | 1.7877 | 1.9053 |

| 11 | Products/services purchased using a mobile channel before the pandemic | 29.76% | 57.19% | 54.78% | 1.3996 | 0.6766 | 0.4834 |

| 12 | Products/services purchased using a mobile channel during the pandemic | 135.74% | 126.47% | 98.82% | 2.0404 | 1.7113 | 0.8387 |

| 13 | Products/services that the respondent would not buy using a mobile channel before the pandemic | 76.71% | 36.26% | 101.10% | 0.9383 | 1.7877 | 1.9053 |

| 14 | Products/services that the respondent would not buy using a mobile channel during the pandemic | 45.04% | 32.17% | 40.45% | 1.4258 | 1.0065 | 0.706 |

| 15 | Products/services purchased using a traditional online channel before the pandemic | 37.67% | 21.67% | 34.24% | 0.4898 | 0.5295 | 1.0809 |

| 16 | Products/services purchased using a traditional online channel during the pandemic | 18.56% | 15.84% | 17.46% | 1.0735 | 1.1595 | 1.0802 |

| 17 | Products/services that the respondent would not buy using a traditional online channel before the pandemic | 43.87% | 18.41% | 34.47% | 0.8319 | 1.901 | 2.2852 |

| 18 | Products/services that the respondent would not buy using a traditional online channel during the pandemic | 18.56% | 15.84% | 17.46% | 1.3996 | 0.6766 | 0.4834 |

| 19 | Type of payment used on mobile devices before the pandemic | 75.23% | 100.89% | 96.00% | 2.0404 | 1.7113 | 0.8387 |

| 20 | Type of payment used on mobile devices during the pandemic | 82.46% | 57.92% | 90.54% | 0.9383 | 1.7877 | 1.9053 |

| 21 | Type of payment used on traditional devices before the pandemic | 78.67% | 106.62% | 73.53% | 0.1921 | 0.5529 | 2.878 |

| 22 | Type of payment used on traditional devices during the pandemic | 75.23% | 100.89% | 96.00% | 3.8968 | 16.5424 | 4.2451 |

| 23 | Preferences regarding delivery methods for mobile shopping before the pandemic | 39.18% | 32.42% | 33.42% | 0.1691 | 0.6345 | 3.7523 |

| 24 | Preferences regarding delivery methods for mobile shopping before the pandemic | 49.85% | 30.73% | 35.89% | 3.9389 | 0.9391 | 0.2384 |

| Fisher-Snedecor inverse test values for the analyzed sample of indicators | 1.6331 | 1.1862 | 0.7263 | ||||

| Fisher-Snedecor inverse test limits for the sample analyzed | 1.4679 | 1.2245 | 1.4866 | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chmielarz, W.; Zborowski, M.; Jin, X.; Atasever, M.; Szpakowska, J. On a Comparative Analysis of Individual Customer Purchases on the Internet for Poland, Turkey and the People’s Republic of China at the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7366. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127366

Chmielarz W, Zborowski M, Jin X, Atasever M, Szpakowska J. On a Comparative Analysis of Individual Customer Purchases on the Internet for Poland, Turkey and the People’s Republic of China at the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability. 2022; 14(12):7366. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127366

Chicago/Turabian StyleChmielarz, Witold, Marek Zborowski, Xuetao Jin, Mesut Atasever, and Justyna Szpakowska. 2022. "On a Comparative Analysis of Individual Customer Purchases on the Internet for Poland, Turkey and the People’s Republic of China at the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic" Sustainability 14, no. 12: 7366. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127366

APA StyleChmielarz, W., Zborowski, M., Jin, X., Atasever, M., & Szpakowska, J. (2022). On a Comparative Analysis of Individual Customer Purchases on the Internet for Poland, Turkey and the People’s Republic of China at the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability, 14(12), 7366. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14127366