Typology of Tactile Architectural Drawings Accessible for Blind and Partially Sighted People

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Context of the Discussion and Motivation of the Research Study

1.2. The Subject, State, and Purpose of the Publication

- -

- a determination of the full spectrum of the typhlographic collection;

- -

- a grouping of the types and sub-types depending on various applications, graphic and material solutions, and method of use.

1.3. Materials and Methods of Research

- typhlographics presented in scientific publications;

- products of Polish and foreign producers (including professional companies that mass-produce typhlographics, as well as companies that produce unique single-copy tactile graphics dedicated to specific places and purposes);

- collections of educational centers and support organizations for the visually impaired, both available for use and stored in archives (including numerous works by anonymous authors and visually impaired people);

- typhlographics available in public spaces (squares, streets, and transportation hubs), public facilities (tourist places and institutions of European cities), and cultural institutions (typhlographics made by artists or employees—both unique works and translations of art for tactile reception).

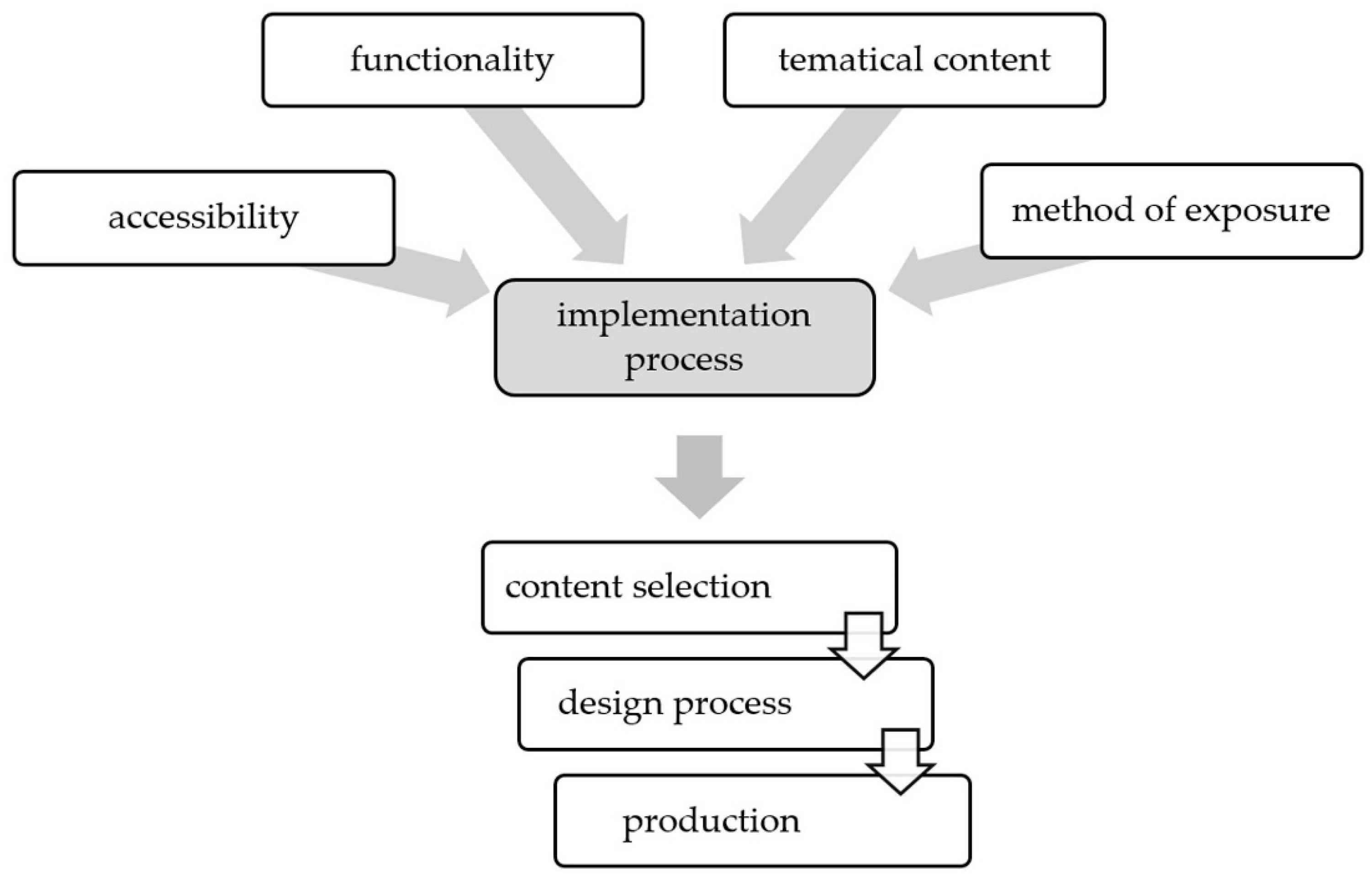

- For whom ?—Who is the recipient of tactile graphics?

- What for ?—What is the purpose and functional scope?

- What ?—What is the content and its cognitive value ?

- Where ?—What is the place and method of use ?

- How ?—What is the scope, and what are the stages and possibilities of the implementation process?

2. Research Results—Typology of Architectural Typhlographs

- sensory accessibility;

- purposefulness (functionality);

- the relation between drawings and the architectural reality;

- content of the drawings;

- method of presentation;

- method of exposition;

- methods of producing typhlographics.

2.1. The Criterion of Sensory Accessibility

- Mono-sensory—tactile drawings—raised-line drawings intended for haptic use (in which visual elements do not constitute the essence of the message), designed mainly for completely blind people.

- Multisensory—raised-line drawings intended for the sense of touch and at least one additional sense to support, complement, or replace the haptic perception, designed for a wider group of users, including visually impaired people. Due to the extended group of users, multisensory typhlographics are also referred to as universal supporting materials.

- Haptic-visual—colored drawings with raised lines, engaging both the sense of sight and touch, intended for users with both or one of the senses mentioned. Therefore, this group of typhlographics can be included in a wider set of the so-called magnigraphy, that is, graphics designed for the visually impaired [37], as in Figure 3.

- Haptic-auditory—raised-line drawings in which the visual elements are not significantly important, and the content is additionally supported by specially designed audio messages.

- Haptic-visual-auditory—colored drawings with raised lines, in which the transmission of information is supplemented by sound messages.

- integrated—soundtrack permanently built-in and accessible via special buttons (e.g., multimedia board or terminal, “touch it” type, or multimedia devices);

- complementary—sound recording available on a special player (e.g., a player with a headset) or played on the user’s devices (e.g., audio systems using Bluetooth, GPS, beacons, etc.).

2.2. The Criterion Regarding the Purposefulness (Functionality) of Typhlographics

- Spatial orientation and safe locomotion—drawings aimed at making it easier for the visually impaired to obtain a valuable and adequate mental image of urbanized space and to implement a planned route of movement or move according to specific rules (including e.g., evacuation).

- Learning spatial orientation and movement—drawings supporting the acquisition of competencies allowing for the use of architectural space without using the sense of sight, including learning the principles of the structure and function of the urban environment. Such drawings introduce concepts and problems related to moving in urban space and familiarize the blind person with typical situations that will or may appear in real space.

- General knowledge of the architectural space—including materials supporting general education and individual human development in the field of architectural concepts, the history of architecture, the architectural styles, the specific objects, the general construction of the architectural objects, architectural curiosities, etc.

- For tourist purposes—supporting materials that facilitate visiting attractive architectural spaces, including historical and contemporary buildings,

- Other purposes, e.g., advertising (the advertisement and promotion of the organization that implements or provides typhlography), commemoration (occasional editions, e.g., anniversary celebrations or the commemoration of an event related to architecture), decorative (graphics that decorate space, book pages, etc.), fun and relaxation (drawings created to make free time more enjoyable), etc.

- presentation—showing the principles of organization and the realistic features of spatial systems (including adaptations of flat graphics presenting architectural content);

- information and warning—graphics communicating the presence of specific elements considered as important or dangerous;

- preservation of information—drawings aimed at registering space to preserve the possibility of later recreating the existing spatial relations;

- instruction—typhlographics giving practical tips on how to use a given space;

- documentation—technical drawings and views constituting a mutual communication tool in the construction and architectural industry;

- prototype—experimental drawings made to illustrate and verify specific architectural concepts [25].

2.3. Reference Criterion: Drawing versus the Presented Architectural Reality

- direct representations of space—drawings referring to a specific, existing architectural space;

- representations based on another representation—adaptations of “ordinary” drawings of architecture to a form readable by the sense of touch;

- the representations that do not have a prototype in real space and are not adaptations of other visual graphics.

- reconstructive (imitative)—drawings corresponding to a specific architectural reality (duplicating or imitating its features and principles of structure and function).

- processed (modified or transformed)—drawings changed by introducing modifications to the space prototype while maintaining some of its features, or drawings transforming the features taken from many spatial images into one drawing (e.g., abstract drawings of space—an example, model, or typical images),

- creative—drawings of a new concept of a non-existent space, in which we distinguish: imaginary drawings—depicting an invented architectural space, and conceptual design drawings—related to creating a future architectural space.

- on a scale—drawings in which the typhlographic image is a faithful representation, or is a reduction or enlargement of the original (it can be made on an architectural scale or at any other scale);

- in the so-called contaminated scale—drawings made in different scales for different directions of the presented space (which may be dictated by the desire for better tactile readability of the image);

- off-scale—drawings that try to capture the overall impression, without attention to the relative proportions of the elements.

2.4. The Criterion of the Content of Tactile Architectural Drawings

- shape—the geometry of the architectural form;

- proportions—the mutual distance and height relations of architectural objects;

- tectonics—the morphological structure of forms and spaces;

- composition—the arrangement of forms and spaces, and the order of the facade;

- material—information on the construction and finishing materials;

- texture—reflecting the features of the floor surface texture, wall surface, or other elements;

- construction and technology—information on the construction methods and techniques;

- color—information on colors.

- entrances—markings of doors, entrance openings, gates, etc.;

- traffic directions—presentation of proposed, desired, or necessary routes of transport;

- numbering—building address numbers, room order numbers—as in Figure 11a,

- instructions for the use of space—information on the assumed function of the space or interior, as in Figure 11b;

- essential elements and important areas—information on important zones or rooms;

- friendly elements—the arrangement and marking of solutions supporting the use of the space or facility;

- barriers and ways to avoid them—the arrangement and marking of unsafe elements and barriers, the creation of safety system elements, etc.

- an image orientation marker—a symbol supporting the orientation of the observer in the drawing space (usually represented by a triangle or a chamfer in the upper right corner of the graphic);

- a spatial orientation marker—symbols facilitating orientation in physical space (e.g., a north arrow or a compass rose of the winds showing geographical directions);

- a scale marker—symbols that enable an estimation of the size of the objects in the drawing (e.g., human silhouette, numerical scale, or graduation scale);

- an observer position marker—a positioning point showing the current location of the observer (e.g., a raised pin or a human silhouette).

- an ideogram—pictorial abbreviation, simplification, synthesis, or archetype of an architectural form;

- the design process—stages of creative work, changes or transformations made within a space or object;

- a logotype—an ancestral coat of arms, emblem, graphic sign of a space or project, or a logo of an organization;

- labels—additional elements complementing or explaining the content of the drawing;

- auxiliary lines—helping to read and understand the presented shapes of the object (e.g., auxiliary lines showing the invisible edges of the object shown in a three-dimensional view);

- dimensions—dimension lines specifying the size and the estimated time needed to cover a given distance.

2.5. The Criterion of the Method of Presenting the Content of Drawings

- maps—cartographic studies of specific spatial systems and structures;

- diagrams—simplified, strongly reduced space drawings;

- plans—top view, two dimensional flat projections of urban spaces/buildings/rooms;

- facades—front view, two dimensional flat projections of external walls of buildings;

- interior elevations—vertical, two-dimensional drawings of internal walls;

- sections—drawings showing a view of the spaces, buildings, and elements as though they had been sliced or cut inside along an imaginary plane;

- silhouettes—outlines and external contours of a building or a group of buildings;

- panoramas and street frontages—drawings showing larger fragments of the city landscape or building sequences;

- views—drawings showing three-dimensional space, made from an axonometric view, perspective, or with elements of perspective;

- details—additional drawings of selected fragments of urban and architectural spaces or elements of interior architecture;

- additional complimentary drawings—representations of elements related to architecture, such as coats of arms, costumes, props for scenography, spatial installations, and paintings with genre scenes, as in Figure 13.

- realistic—maintaining the highest possible reliability and truthfulness of the image when compared to the original;

- technical—with the highest precision and accuracy possible;

- geometrized—to simplify the objects and reduce them to simple solids and geometric shapes;

- plastic—drawings made intentionally in an impressionable, intuitive way, ensuring aesthetic attractiveness.

- Semi-flat—those in which the content is presented on a plane with raised lines, patterns, areas, symbols, etc.

- Semi-spatial, also called 2.5D drawings—representations in which the content has been developed in the form of raised solid forms, reflecting the actual geometry and position of the objects, as well as their sphericality, curvature, and obliquity. Upon reception, they resemble models.

- Sometimes, embossed solid forms are combined with raised lines, patterns, and symbols.

- raised line tactile drawings (contour or texture);

- embossed shape tactile drawings (raised surface or objects), with different characteristics: single level, multi-level embossed, rounded- (-domed) embossed, or sculpted-embossed;

- mixed (e.g., embossed-textured drawing).

- contour and linear outline—showing the external outline of the object;

- contour-textural—those in which the outer contour is filled with a tactile texture;

- textural—drawings without contours, in which the areas are covered with tactile textures.

- Without spatial depth—semi-flat drawings of spatial objects shown in the top view flat projection.

- With a suggestion of spatial depth—semi-flat drawings of spatial objects captured with such effects as the mutual overlapping of the objects in the scene (showing objects partly hidden one behind another), reducing objects’ size or slightly elevating or side-shifting objects standing further away on the drawing plane, and drawings with shadows (according to the authors, the examined examples are most likely manufacturing mistakes, because these types of plasticizing effects are intended only for visual reception, while their use in typhlographics intended for the visually impaired may disturb the reception of the content and even mislead the recipient).

- Including spatial depth graphic effects—semi-flat or semi-spatial drawings imitating the stereoscopic effects that a sighted person obtains when seeing architectural scenes, and tactile drawings transferring depth effects commonly used in visual graphics, like in painterly, atmospheric, and luminous perspective (where the intensity of the colors, light, and the contrast decreases with the distance of the objects).

- Primary views—raised-line, canonical images of three-dimensional objects presented in two dimensions, in the form of parallel projections on a plane, i.e., plans, elevations, sections, etc.

- Perspective—views showing a three-dimensional effect, including a perspective based on the principles of geometry called linear (one-point, two-point, and three-point); a curvilinear perspective (four-or-above-point), which includes image distortions; and a multipoint perspective that shows objects positioned to each other at a different angle. In addition, there is also a reverse perspective (also called inverted, divergent, or Byzantine perspective), where the point of convergence of the perspective lines is in front of the image plane, and not behind it, as in a linear perspective. [39]

- Semi-perspective—in typhlographs, this is a simplification of a one-point parallel perspective, where the primary view is combined with perspective elements by adding perspective side views.

- Pseudo-perspective/empirical perspective—projections that differ significantly from the laws of vision and are not based on the principles of geometry. These are views that are a free drawing of space, often without preserving the three-dimensionality of objects and the principles of scaling them in space. Such representations can be found especially in pre-Renaissance visual works before the principles of the geometric perspective were learned. Examples of the pseudo-perspective appear in prehistoric cave paintings, Egyptian art, children’s art, and contemporary pseudo-primitive graphics. In these works, we find various spatial compositions that are used to provide the impression of space. Additionally, we can distinguish perspectives: overlapping composition (objects cover each other, creating an impression of depth), vertical perspective (more distant elements are placed higher), strip perspective (figures are grouped into a system of horizontal rows/stripes), topographic perspective (primary side views are freely arranged around the drawing of a plan, which resembles a map), or an intentional/hierarchical perspective (the most important object is presented on a larger scale than the surroundings) [40,41].

- A “contaminated” or deformed perspective—completely arbitrary use of spatial effects, often used only on selected elements of the image to highlight depth, relief, or curvature, not reflecting the real geometry of the object.

- Mixed projection perspective—a spatial drawing containing a compilation of various known variants of perspectives, often freely distributed in the drawing area.

- Axonometric view—a type of parallel projection of space using the coordinate axes system, corresponding to three dimensions. Axonometric drawings are created according to specific geometric rules. Depending on the angle of inclination of the axis, many sub-types of axonometric views can be distinguished (including auxiliary multi-view projection; isometric, dimetric, trimetric, and oblique projection; and cabinet, cavalier, and military projections). This is a type of drawing in which the real dimensions of objects are preserved in at least one selected direction, which makes this type of space representation widely used in technical drawing and architecture.

- Primary multi-view projection—a non-photorealistic multi-element drawing, created by showing views arranged next to each other obtained from carefully selected canonical observation points. The image of the object is projected onto the sides of a geometric cube located around the object. One can draw six different sides, but typically three views are used to represent a three-dimensional object (front, top, and end view) [42,43].

- epitomic—presenting the most characteristic approach to a given architectural or urban space [44] (pp. 210–212);

- faithful/precise—showing the object in a reliable way, systematized way, comprehensive way, correct way, and so on;

- accenting—drawings that emphasize and highlight some elements and features and spatial phenomena for better visibility and understanding;

- iconic—simplifying objects or spaces and synthesizing their most important features [45];

- symbolic—drawings representing broader cognitive content in architecture;

- conventional—in which the approach to space does not play a significant role.

2.6. The Criterion of the Method of Exposure

- stationary—permanent displays, available only on-site and set in a strictly defined place (sometimes changed), often directly next to the presented space, as in Figure 16a–d;

- portable—materials enabling easy transport from place to place, taking on the road or flexible positioning in different places, as in Figure 16e,f.

- self-functioning images;

- drawings installed on various types of spatial displays (boards, tables, pedestals, stands, posts, poles, or pylons), as in Figure 16a–d;

- surface images, made on the surfaces of planes and various objects (e.g., on planes of space—floors, walls; on elements of equipment—city furniture; elements of road infrastructure, etc.).

- separate single drawings—individual cards, sheets, signs, forms, boards, molds, engravings, and so on;

- single drawings grouped into sets—folders, binders, and briefcases that can be freely expanded with new images or divided depending on the user’s needs (with the possibility of taking any set of drawings for a trip, for visiting the museum, etc.), as in Figure 16f;

- fixed, permanently stapled sets—predefined, inseparable sets of tactile drawings, for example, book publications (manuals, guides, albums, atlases, playbooks, calendars, etc.);

- series—sets of several publications forming a coherent whole (e.g., thematic series), as in Figure 16e.

2.7. The Criterion for Producing Tactile Drawings

- Handmade—(made by hand or with the use of some utensils) for example, drawn, painted, formed, sculpted, molded, glued, imprinted, pressed, stitched, embroidered, knitted, stretched, bent, stacked, poured, scratched, grooved, woven, cut, torn, etc., as shown in Figure 18a.

- Mechanically manufactured—printed with a braille dot-printer, printed with 3D printers, printed on heat-sensitive capsule paper, using screen printing, using flock printing, formed with stamping machines or presses, thermoformed, layered, sprayed, varnished, cast, engraved, milled, etc., as shown examples in Figure 18b–d.

3. Discussion

- a systematized, comprehensive overview of the full spectrum of solutions in the field of architectural typhlographics;

- the unification of nomenclature concerning the features of architectural typhlographs;

- the creation of a basis for conducting qualitative research in the field of architectural typhlographics (including constructing precise and systematized descriptions of any typhlography, conducting comparative and evaluative research, and testing the effectiveness of the given solutions depending on the adopted variables).

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mashburn, A.J.; LoCasale-Crouch, J.; Pears, K.C. Kindergarten Transition and Readiness: Promoting Cognitive, Social-Emotional, and Self-Regulatory Development; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; p. 212. ISBN 9783319902005. [Google Scholar]

- Kłopotowska, A.; Kłopotowski, M. Dotykowe Modele Architektoniczne w Przestrzeniach Polskich Miast (Tactile Architectural Models in the Spaces of Polish Cities); Vol. I. Standardy; Oficyna Wydawnicza Politechniki Białostockiej: Białystok, Poland, 2018; pp. 9, 47. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Vesely, D. Architecture in the Age of Divided Representation: The Question of Creativity in the Shadow of Production; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004; p. 50. ISBN 9780262220675. [Google Scholar]

- Polski Związek Niewidomych. Wybrane Zagadnienia z Orientacji Przestrzennej Niewidomych (Selected Issues of Spatial Orientation of the Blind); Vol. I, Vol. II.; PZN: Warsaw, Poland, 1974. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Jakubowski, M. Tyflografika-ksero dla niewidomych (Tyflografika-Photocopying for the Blind); Foundation Institute for Regional Development: Poland, Krakow, 2009; Volume 2, pp. 3–7. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Więckowska, E. Zasady Redagowania Tyflografiki (Principles of Editing Typhlographics); Foundation Institute for Regional Development: Poland, Krakow, 2009; Volume 3, pp. 7–13. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Edman, P. Tactile Graphics; AFB Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992; ISBN 9780891281948. [Google Scholar]

- Braille Authority of North America; Canadian Braille Authority L’Autorité Canadienne du Braille. Guidelines and Standards for Tactile Graphics; Web Version—February 2012; The Braille Authority of North America. 2010. Available online: https://www.brailleauthority.org/tg/web-manual/index.html (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Jakubowski, M. Tyflografika-Historia i Współczesność, Metody i Technologie (Typhlographics-History and Modern Times, Methods and Technologies); Foundation Institute for Regional Development: Poland, Krakow, 2009; Volume 1, pp. 36–40. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Wysocki, M. Projektowanie Otoczenia dla osób Niewidomych. Pozawzrokowa Percepcja Przestrzeni8 (Designing the Environment for the Blind. Non-Visual Perception of Space); Wydawnictwa Politechniki Gdańskiej: Gdansk, Poland, 2010. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Steinfeld, E.; Maisel, J.L. Universal Design: Creating Inclusive Environments; John Wiley & Sons: Singapore, 2012; ISBN 9780470399132. [Google Scholar]

- Maisel, J.L.; Steinfeld, E.; Basnak, M.; Smith, K.; Tauke, M.B. Inclusive Design: Implementation and Evaluation; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 9781317494928. [Google Scholar]

- Murugkar, K.; Mullick, A. Can touch substitute vision? An empirical study about how the visually impaired comprehend shapes. In Universal Design 2014: Three Days of Creativity and Diversity: Proceedings of the International Conference on Universal Design, UD 2014 Lund, Sweden, June 16–18, 2014; Caltenco, H.A., Hedvall, P.O., Larsson, A., Eds.; IOS Press: Amsterdam, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 35–43. ISBN 9781614994039. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, J.M. Drawing & the Blind: Pictures to Touch, 1st ed.; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1993; ISBN 300054904. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, J.M.; Juricevic, I. Foreshortening, Convergence and Drawings from a Blind Adult. Perception 2006, 35, 847–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, J.M.; Juricevic, I. Blind Man Draws Using Diminution in Three Dimensions. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2006, 13, 506–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Heller, M.A.; Kennedy, J.M.; Clark, A.; Mc Carthy, M.; Borgert, A.; Fulkerson, E.; Wemple, L.; Kaffel, N.; Duncan, A.; Riddle, T. Viewpoint and Orientation Influence Picture Recognition in the Blind. Perception 2006, 35, 1397–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kaneko, T.; Fujiyoshi, M.; Oouchi, S. Comprehending and Making Drawings of 3D Objects by Visually Impaired People: Research on Drawings of Geometric Shapes by Various Methods of Projection. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs; ICCHP 2010. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 6180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanni, N.; Furferi, R.; Governi, L.; Volpe, Y. Tactile 3D bas-relief from single-point perspective paintings: A computer based method. J. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2014, 11, 5667–5680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reichinger, A.; Carrizosa, H.G.; Travnicek, C. Designing an Interactive Tactile Relief of the Meissen Table Fountain. In Computers Helping People with Special Needs; ICCHP 2018. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; Volume 10897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kłopotowska, A. Brajlon jako metoda zapisu przestrzeni architektonicznej w edukacji uczniów z dysfunkcją widzenia (Braille as a method of recording architectural space in the education of visually impaired students). In Definiowanie Przestrzeni Architektonicznej. Zapis Przestrzeni Architektonicznej (Defining the Architectural Space. Record of Architectural Space); Vol. II; Misiągiewicz, M., Kozłowski, D., Eds.; Politechnika Krakowska: Krakow, Poland, 2013; pp. 229–233. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Kłopotowska, A. Detal Architektoniczny w Poznaniu Bezwzrokowym (Architectural Detail in Extravisual Cognition); Technical Transactions. Architecture; Cracow University of Technology: Cracow, Poland, 2012; pp. 269–273. [Google Scholar]

- Kłopotowska, A. Doświadczanie Przestrzeni w Rehabilitacji Osób z Dysfunkcja Wzroku. Sztuka a Tyflorehabilitacja (Experiencing Space in the Rehabilitation of Visually Impaired People. Art and Typhlo-Rehabilitation); Oficyna Wydawnicza PB: Bialystok, Poland, 2016. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Kłopotowska, A.; Magdziak, M. Tactile Architectural Drawings—Practical Application and Potential of Architectural Typhlographics. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misiągiewicz, M. O Prezentacji Idei Architektonicznej (about Presentation of an Architectural Idea); Politechnika Krakowska: Kraków, Poland, 1999. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Schaller, T.W. The Art of Architectural Drawing: Imagination and Technique; John Wiley & Sons: Singapore, 1997; ISBN 9780471284659. [Google Scholar]

- Yee, R. Architectural Drawing: A Visual Compendium of Types and Methods; John Wiley & Sons: Singapore, 2012; ISBN 9781118012871. [Google Scholar]

- Ching, F.D.K. Architectural Graphics; John Wiley and Sons: Singapore, 2012; ISBN 9781118041499. [Google Scholar]

- Row, D.; Reid, T.J. Geometry, Perspective Drawing, and Mechanisms; World Scientific Publishing Company: Singapore, 2012; ISBN 9789814343824. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amelio, J. Perspective Drawing Handbook; Tudor Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 9780486317304. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning, W.V. Changing Images of Pictorial Space: A History of Spatial Illusion in Painting; Syracuse University Press: Syracuse, NY, USA, 1991; ISBN 9780815625087. [Google Scholar]

- Bouleau, C. The Painter’s Secret Geometry: A Study of Composition in Art; Dover Publications, Inc.: Mineola, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 9780486780405. [Google Scholar]

- Willats, J. Art and Representation: New Principles in the Analysis of Pictures; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1997; ISBN 9780691087375. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, J.M. A Psychology of Picture Perception; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Jolley, R.P. Children and Pictures: Drawing and Understanding; John Wiley & Sons: Singapore, 2009; ISBN 9781405105439. [Google Scholar]

- Willats, J. Making Sense of Children’s Drawings; Psychology Press, Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2006; ISBN 9781135624989. [Google Scholar]

- Kalbarczyk, A. Widzieć Dotykiem i Słuchem. Dźwięk, Tyflografika i Magnigrafika. Kompendium; (See by touch and hearing. Sound, Typhlographics and Magnigraphy. Compendium); Fundacja Szansa dla Niewidomych: Warsaw, Poland, 2008. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Ammon, S.; Capdevila-Werning, R. The Active Image: Architecture and Engineering in the Age of Modeling; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; p. 75. ISBN 9783319564661. [Google Scholar]

- Raynaud, D. Optics and the Rise of Perspective; Bardwell Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero, R.; Díaz Vera, J.E. Sensuous Cognition: Explorations into Human Sentience: Imagination, (E)motion and Perception, Applications of Cognitive Linguistics [ACL]; Walter de Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2013; Volume 22, pp. 142–143. ISBN 9783110300772. [Google Scholar]

- Arnheim, R. Art and Visual Perception: A Psychology of the Creative Eye; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1965; pp. 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- Pipes, A. Foundations of Art and Design; Laurence King Publishing: London, UK, 2003; pp. 102–103. ISBN 9781856693752. [Google Scholar]

- Panotopoulou, A.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, T.; Yang, X.-D.; Whiting, E. Tactile Line Drawings for Improved Shape Understanding in Blind and Visually Impaired Users. ACM Trans. Graph. 2020, 39, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, J.W.; Poortinga, Y.H.; Segall, M.H.; Dasen, P.R. Cross-Cultural Psychology: Research and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; pp. 210–212. ISBN 9780521646178. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, D. Images in Mind: Statues in Archaic and Classical Greek Literature and Thought; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 89–90. ISBN 9780691094885. [Google Scholar]

| Initial Research Questions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| For Whom ? | What for ? | What ? | Where ? | How ? | ||

| Various groups of recipients | Possibility of practical use | Thematic content in the field of architectural knowledge | Forms of presentation | Precision and fidelity of information transfer | Various drawing conventions | Different production methods |

| Accessibility to specific human senses | For various tasks related to the functioning of blind people in physical and social spaces | Types of space and objects including cognitive elements of drawing | Various ways of using and locating of typhlographs depending on the expected cognitive results and number of users | Relation to the original information (relationship between the object of representation and tactile drawing) | Drawing conventions used intentionally to obtain the appropriate cognitive values of a drawing, supporting specific tasks | Production methods leading to different final effects and characterized by different economics |

| PRIMARY CRITERIA → 1 | IMPLEMENTATION CRITERIA | |||||

| Content Selection→ 1 | Design Process→ 1 | Production | ||||

| Criterion of sensory accessibility | Criterion of purposefulness (functionality) | Criterion of the content | Criterion of the method of exposure | Reference criterion | Criterion of the method of presenting the content | Criterion for producing tactile drawings |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Duniewicz, A.; Magdziak, M. Typology of Tactile Architectural Drawings Accessible for Blind and Partially Sighted People. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7847. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137847

Duniewicz A, Magdziak M. Typology of Tactile Architectural Drawings Accessible for Blind and Partially Sighted People. Sustainability. 2022; 14(13):7847. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137847

Chicago/Turabian StyleDuniewicz, Agnieszka, and Monika Magdziak. 2022. "Typology of Tactile Architectural Drawings Accessible for Blind and Partially Sighted People" Sustainability 14, no. 13: 7847. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137847

APA StyleDuniewicz, A., & Magdziak, M. (2022). Typology of Tactile Architectural Drawings Accessible for Blind and Partially Sighted People. Sustainability, 14(13), 7847. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137847