Domestic and Imported Food Product Recalls in Japan: Trend Analysis and Preventive Measures

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection of Food Product Recall Data

2.2. Classification and Trend Analysis of Food Product Recalls

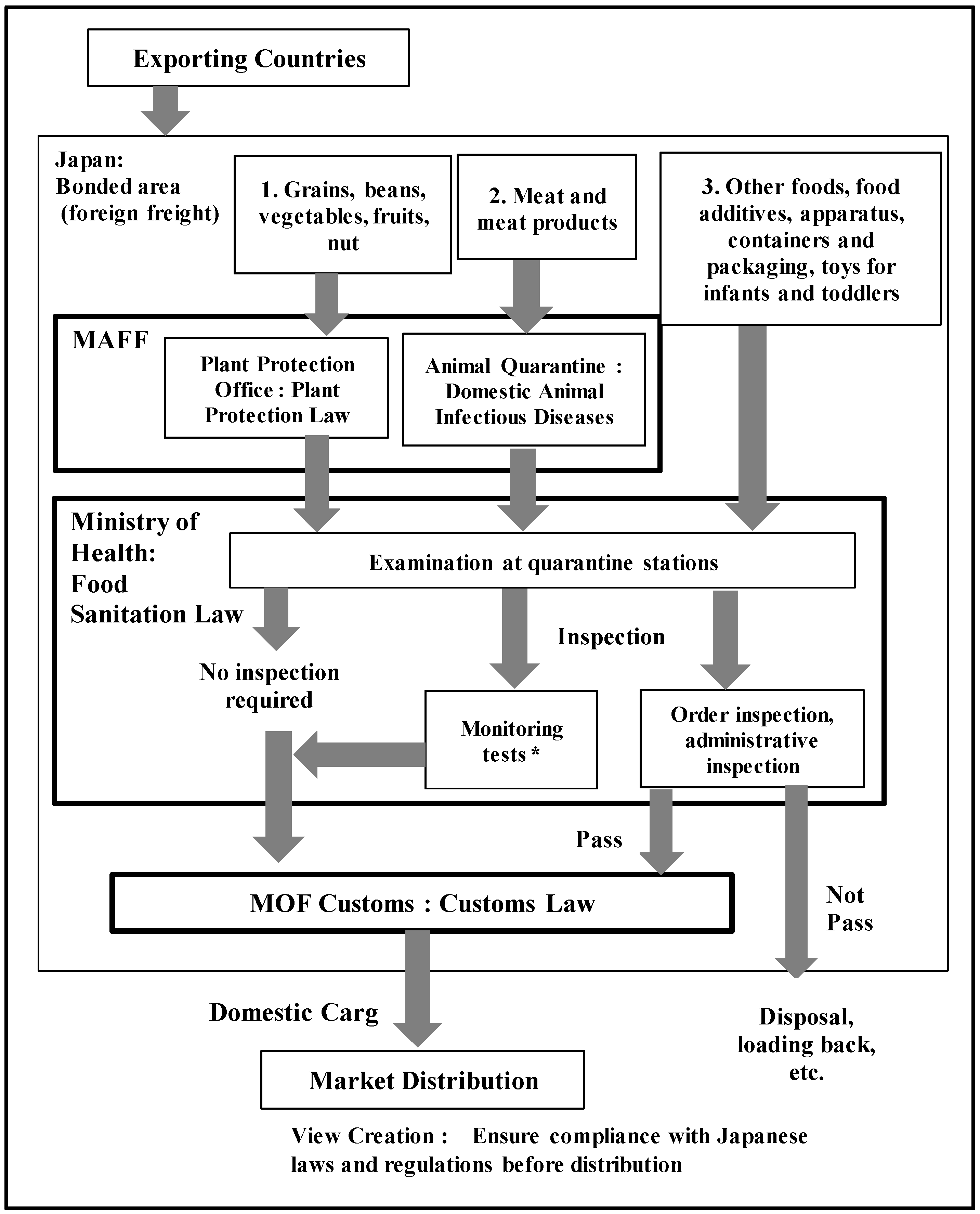

2.3. Domestic Distribution of Imported Foods in Japan

2.4. Collection of Data on Cases of Violations of Imported Foods in Quarantine Inspection

3. Results

3.1. Approximate Food Loss

3.2. Manufacturer-Attributed Recalls

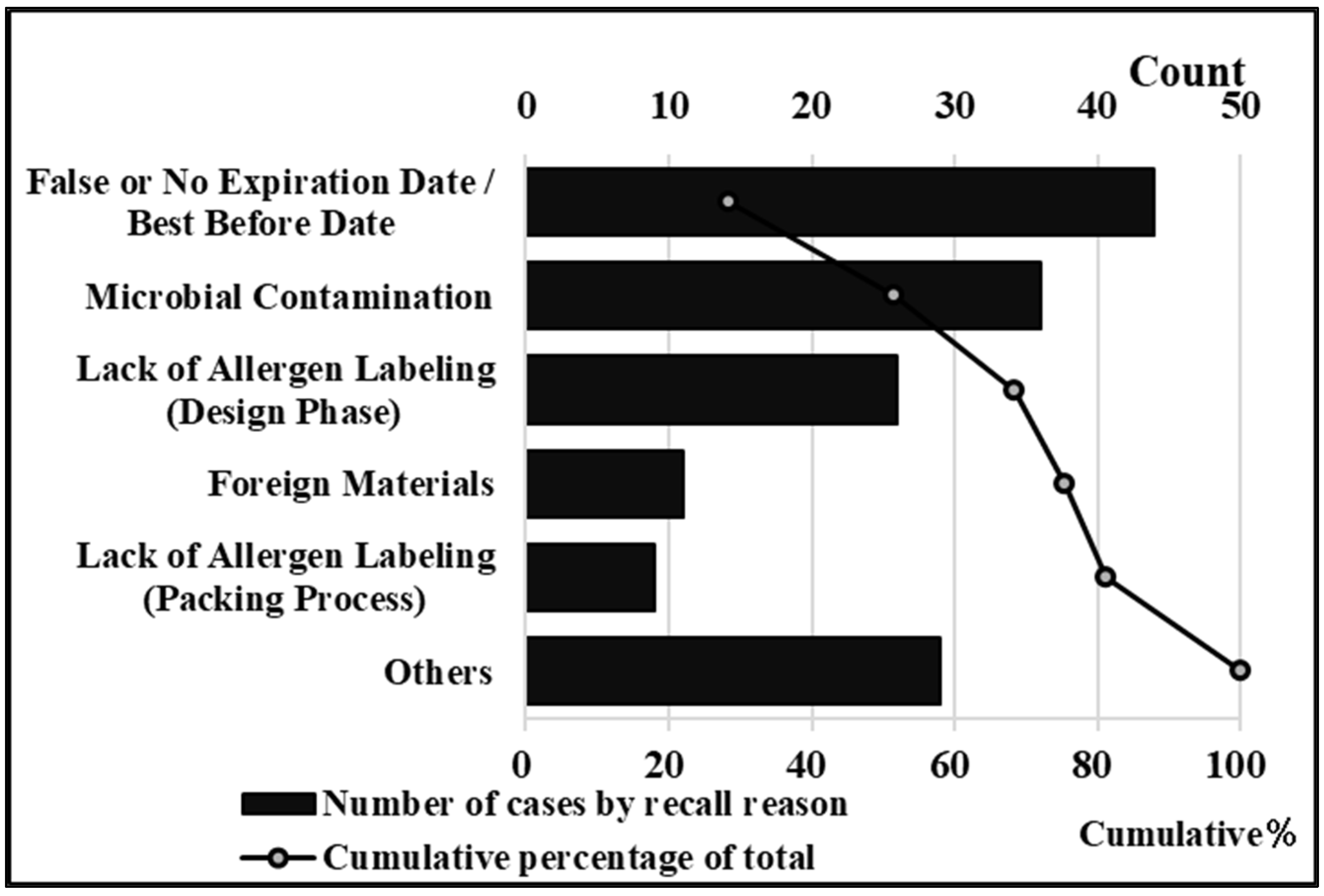

3.2.1. Trend Analysis Based on Violation of Relevant Laws and Regulations and Causes of Recalls

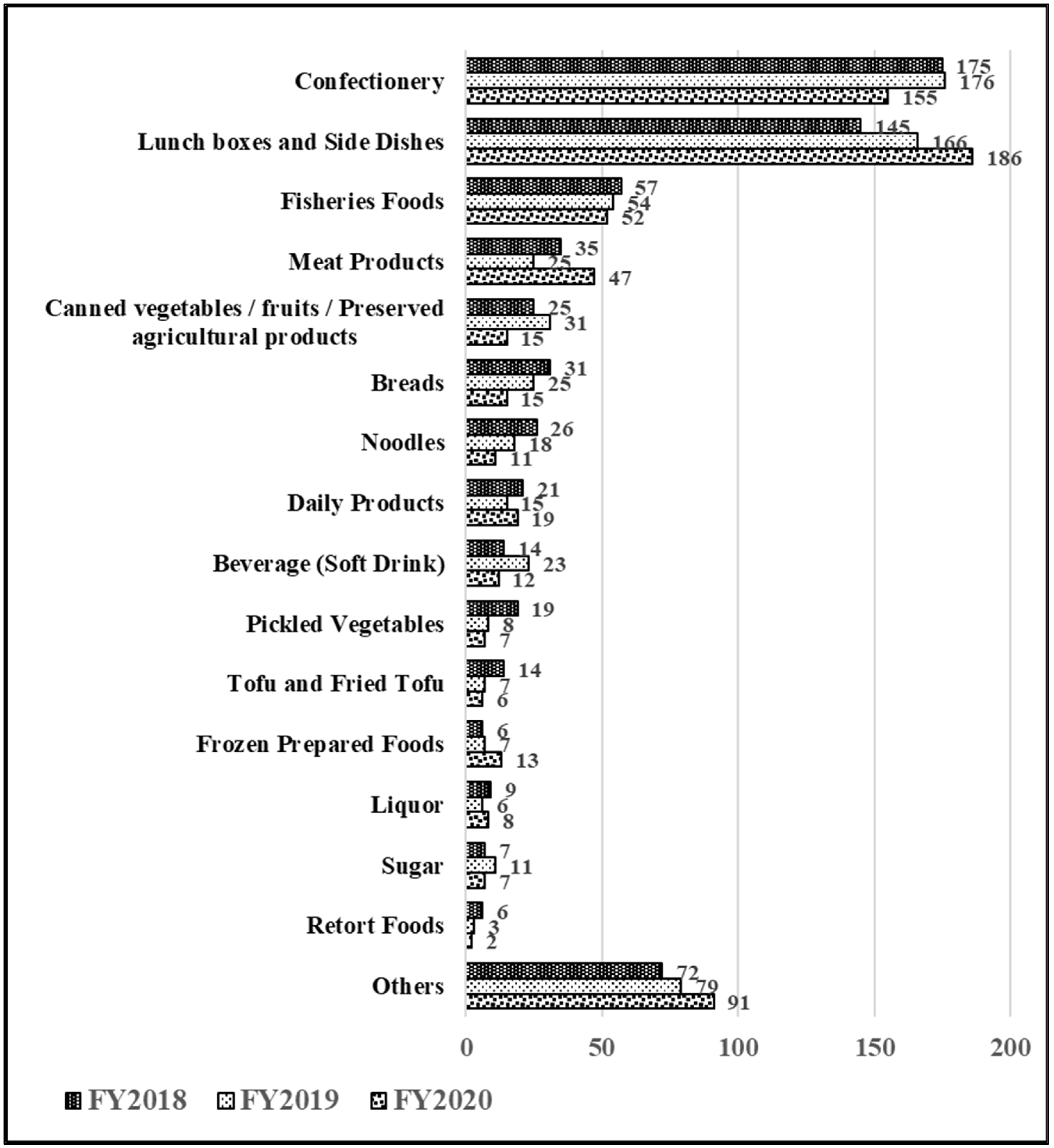

3.2.2. Trend Analysis for the Classification of Recalls by Food Category

- Confectionery category

- Lunch boxes/side dishes category

3.2.3. Measures to Prevent Recalls by Manufacturers

3.3. Importer-Attributed Recalls

3.3.1. Overview of Imports in Japan

3.3.2. Trend Analysis of Quarantine Violations

3.3.3. Relationship between Quarantine Violations and Recall of Imported Foods

3.3.4. Potential Measures to Prevent Importer-Attributed Recalls

4. Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Outline of the Partial Revision of the Food Sanitation Law (Promulgated on 13 June 2018). Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/11131500/000345946.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- Summary on the Current Status of Food Product Recalls, Consumer Safety Expert Committee. Available online: https://www.cao.go.jp/consumer/iinkaikouhyou/2013/houkoku/201308_houkoku.html (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- Matsumoto, T. Consideration on countermeasures for food product recall prevention in Japan. J. Food Syst. Res. 2019, 26, 367–372. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Summary of Import and Export of Agricultural, Forestry and Fishery Products. 2020. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/tokei/kouhyou/kokusai/houkoku_gaikyou.html (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- Matsumoto, T. Obligation of notification of voluntary recall and trend analysis of recent food product recall. Food Ind. Tomorrow 2021, 6, 31–39. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto, T. Obligation of notification of voluntary recall and countermeasures for food product recall prevention. Mon. Food Fact. Manag. 2021, 6, 30–35. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Kanayama, A.; Kaku, K. Risk of imported food products assumed from cases of oversea food poisoning. Jpn. J. Public Health 2013, 60, 697–704. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Iguchi, N.; Terazaki, M. Product Recall 2012; ABA Section of International Law: Chicago, IL, USA, 2012; pp. 82–85. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of the Environment. 2030 Agenda/SDGs for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/earth/sdgs/index.html (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Consumers Affairs Agency. Reference Materials Related to Food Loss Reduction. 2020. Available online: https://www.caa.go.jp/policies/policy/consumer_policy/information/food_loss/efforts/assets/efforts_210826_0001.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. The Situation Surrounding Food Loss and Recycling. 2020. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/shokusan/recycle/syoku_loss/attach/pdf/161227_4-157.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- The Japan Food Industry Association. Food Recall Information. Available online: https://www.shokusan.or.jp/news/5087/ (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Consumer Affairs Agency. Recall Information. Available online: https://www.recall.caa.go.jp/ (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Food Inspection Division, Tokyo Quarantine Station. Flow of Procedures for Import Notification of Foods, etc. Available online: https://www.forth.go.jp/keneki/tokyo/kanshi_hp/a003.html (accessed on 28 May 2021).

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Import Procedure Based on the Food Sanitation Law. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/shokuhin/yunyu_kanshi/kanshi/index.html (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- Plant Protection Station. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/pps/ (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- Veterinary Quarantine. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/aqs/ (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Import Procedure: Import Procedure under the Food Sanitation Law. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/0000144562.html (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Survey Result on the Introduction Status of HACCP System in the Food Manufacturers. Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/shokusan/koudou/what_haccp/attach/pdf/h_toukei-12.pdf (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- Saito, T. Toward the reduction of printing accident in expiration date and food label. Mon. HACCP 2018, 20, 33–37. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Komaki, E. Food labeling discrepancy prevention utilizing HACCP technique. Food Sci 2018, 10, 64–73. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare. Violation Cases in Quarantine Station Inspections. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/kenkou_iryou/shokuhin/yunyu_kanshi/ihan/index.html (accessed on 31 May 2021).

- Bai, L.; Ma, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Gong, S. Implementation of HACCP system in China: A survey of food enterprises involved. Food Control 2007, 18, 1108–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodd, C.; Powell, D. Regulatory management and communication of risk associated with Escherichia coli O157:H7 in ground beef. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2009, 6, 743–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.; Zhou, J.; Ye, J. Adoption of HACCP system in the Chinese food industry: A comparative analysis. Food Control 2008, 19, 823–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Bir, C.; Widmar, N.O.; Sayal, P. Initial reports of foodborne illness drive more public attention than do food recall announcements. J. Food Prot. 2021, 84, 1150–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, M.; Zhou, C.; Gu, G.; Liang, J.; Hou, X.; Wang, M.; Wei, P. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of retail-meat-borne Salmonella in southern China during the years 2009–2016: The diversity of contamination and the resistance evolution of multidrug-resistant isolates. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 333, 108790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blickem, E.R.; Bell, J.W.; Baumgartel, D.M.; DeBeer, J. An analysis of tuna recalls in the United States, 2002 through 2020. J. Food Prot. 2021, 85, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Q.; Dewey-Mattia, D.; Subramhanya, S.; Cui, Z.; Griffin, P.M.; Lance, S.; Lanier, W.; Wise, M.E.; Crowe, S.J. Food recalls associated with foodborne disease outbreaks, United States, 2006–2016. Epidemiol. Infect. 2021, 149, e190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herod, A.; Goodridge, L.; Rohde, J. Recalls of foods due to microbial contamination classified by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, 2000 to 2017. J. Food Prot. 2019, 82, 1901–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, C.; Luo, Y.; Zhu, W. Food safety trust, risk perception, and consumers’ response to company trust repair actions in food recall crises. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liao, C.; Zhou, X.; Zhao, D. An augmented risk information seeking model: Perceived food safety risk related to food recalls. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Year | A: Number of Recalls | B: Number of Companies That Announced the Quantity of Collection | C: Number of Products to Be Collected × Total Content (Amount Collected by Company B) Unit: 10,000 tons | D: Estimated Amount of Food Loss = C × A/B (100% Conversion) Unit: 10,000 tons | (Reference) Ratio (%) of Food Manufacturers to 1.21 Million tons of Food Loss in 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 791 | 193 | 3.08 | 12.62 | 10.43 |

| 2019 | 770 | 225 | 1.18 | 4.04 | 3.34 |

| Classification and Related Laws | Reason for Recall | Number of Occurrences | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FY2018 | FY2019 | FY2020 | ||

| A. Attributable to the manufacturing process (packaging process) | 282 | 244 | 303 | |

| Food Labeling Law | A1. Best-before date Printing error (printing error, no printing) | 113 | 85 | 85 |

| A2. Expiration date Printing error (printing error, no printing) | 56 | 55 | 60 | |

| A3. Mistakes and omissions in allergen labeling | 85 | 74 | 124 | |

| A4. Incorrect labeling | 7 | 15 | 14 | |

| Food Sanitation Law | B1. Defective packaging (possible microbial contamination) | 21 | 15 | 18 |

| B2. Contamination (part of packaging) | 0 | 0 | 2 | |

| B. Caused by the manufacturing process (other than the packaging process) | 212 | 212 | 166 | |

| Food Sanitation Law | B1. Microbial contamination | 92 | 74 | 72 |

| B2. Foreign material contamination | 67 | 77 | 42 | |

| B3. Deviations from specifications and standards | 24 | 12 | 19 | |

| B4. Allergen contamination | 8 | 8 | 4 | |

| B5. Poor sterilization/unsterilization | 6 | 5 | 15 | |

| B6. No business license (other) | 9 | 27 | 8 | |

| Act against Unjustifiable Premiums and Misleading Representations | B7. Falsification of origin of raw materials by the business operator | 4 | 2 | 0 |

| Food Labeling Law | B8. Incorrect input/use of ingredients, incorrect packaging | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| B9. Missing allergen labeling (incorrect use of ingredients) | 0 | 5 | 2 | |

| Measuring Method | B10. Insufficient quantity | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| C. Arising from the product design stage. | 153 | 151 | 125 | |

| Food Labeling Law | C1. Mistakes or omissions in allergen labeling | 116 | 123 | 93 |

| C2. Mistakes in batch labeling (ingredients, storage methods, etc.) | 21 | 17 | 17 | |

| C3. Mistakes in display of nutrition facts | 4 | 1 | 5 | |

| Food Sanitation Law | C4. Incorrect use of food additives (2) Other | 11 | 9 | 8 |

| C5. Incorrect use of food additives (2) Other | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| D. Caused by raw materials and packaging materials used in manufacturing | 15 | 47 | 52 | |

| Food Sanitation Law | D1. Violation of pesticide residue and veterinary drugs | 5 | 16 | 14 |

| D2. Detection of radioactive materials | 5 | 3 | 4 | |

| D3. Foreign material contamination (including harmful plants and chemicals) | 3 | 14 | 16 | |

| D4. Microbial contamination (including defective packaging) | 1 | 3 | 16 | |

| D5. Violation of food additive use standards | 0 | 5 | 0 | |

| D6. Cross-contamination of allergens | 0 | 2 | 1 | |

| Food Labeling Law | D7. allergen labeling missing (wrong information on raw materials), etc. | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Act against Unjustifiable Premiums and Misleading Representations | D8. Raw material suppliers disguising the origin of raw materials | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 662 | 654 | 646 | |

| Process/Stage | Reason for Recall | Probable Cause | Countermeasure Plan |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing Process | Incorrect or no indication of best-before-date or expiration date | Missetting or printing forgotten in the packaging process | Establishment of a check system for work orders before production, confirmation of deadlines in process control, confirmation before shipment, etc. |

| Allergen labeling missing (product design stage) | Due to allergen labeling error in the display creation at the design stage | Confirmation of legal compliance through design review in ISO9001: 2015 | |

| Microbial Contamination | In particular, mold contamination during packaging after a heating process such as baking or contamination from the working environment or workers if there is no heating process | HACCP systems, including general HACCP (including HACCP controls) Strengthening food safety management systems such as JFS-C certification | |

| Foreign Material Contamination | Origin of raw materials, introduction of foreign matter, generation in manufacturing process, etc. | ||

| Allergen labeling missing (product design stage) | Labeling error in packaging process | Establishment of a check system for work orders before production, confirmation of deadlines in process control, confirmation before shipment, etc. | |

| Product Design and Development Stage | Allergen labeling and other labeling errors |

|

|

| FY2018 | FY2019 | FY2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of reports (millions) | 2.34 | 2.43 | 2.48 |

| Reported weight (unit: million tons) | 32.3 | 33.8 | 34.2 |

| Number of quarantine inspections | 206,000 | 206,000 | 224,000 |

| Inspection rate (number of inspections/number of reports × 100, unit: %) | 8.8 | 8.5 | 9.0 |

| Number of violations | 780 | 843 | 653 |

| Violation rate (number of violations/number of inspections × 100, unit: %) | 0.38 | 0.41 | 0.29 |

| Top 10 Countries in Terms of Imports | Share of Import Value (%) | Main Imported Foods | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Country Name | FY 2018 | FY 2019 | FY2020 | |

| 1 | USA | 18.7 | 17.3 | 17.5 | Corn, beef, pork, soybeans, fresh and dried fruits |

| 2 | China | 12.9 | 12.6 | 13.4 | Frozen Vegetables, poultry products, soybean oil cake, fresh vegetables, unagi (prepared) |

| 3 | Canada | 6.1 | 6.0 | 5.8 | Pork, rapeseed (for oil production), wheat, soybeans |

| 4 | Thailand | 5.9 | 5.9 | 5.8 | Chicken preparations, poultry, pet food, shrimp preparations |

| 5 | Australia | 5.9 | 5.7 | 5.1 | Beef, sugar, natural cheese, wheat |

| 6 | Vietnam | 2.9 | 3.1 | 3.9 | Shrimp, shrimp preparations, coffee beans (raw beans), squid |

| 7 | Brazil | 2.7 | 3.8 | 3.8 | Corn, chicken, coffee beans (raw beans), soybean oil cake, soybeans |

| 8 | Indonesia | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.7 | Shrimp and palm oil |

| 9 | Italy | 3.4 | 3.2 | 3.5 | Alcoholic beverages, olive oil, tomatoes (preparations), and spaghetti |

| 10 | Korea | 2.9 | 3.0 | 3.1 | Skipjack and tuna, fresh vegetables, alcoholic beverages, sweetened food products |

| Total import value | |||||

| USD 1 billion * | 88.7 | 87.3 | 81.6 | ||

| Japanese JPY, Unit: trillion JPY | 9.7 | 9.5 | 8.9 | ||

| FY | Area * | Items Related to the Food Sanitation Law | Total | Violations in Major Countries (5% or More of the Total; Number of Violations after Country) Number of Violations after Country) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Compliance with Microbial Standards | Mycotoxin (e.g., Aflatoxin) Detection | Detection of Pesticide Residues and Antibiotics | Violation of Food Additive Use Standards | Detection of Chemical Substances (e.g., Cyanogen) | Other Nonconformance | |||||

| 2018 | Subtotal/Total | 267 | 153 | 143 | 112 | 37 | 68 | 780 | ||

| Regional | North America (Including USA) | 41 | 93 | 2 | 10 | 1 | 7 | 154 | USA: 142 | |

| USA | 31 | 93 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 7 | 142 | |||

| Middle and South America | 5 | 3 | 25 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 40 | |||

| Europe | 29 | 5 | 4 | 37 | 23 | 19 | 117 | Italy: 43 | ||

| Middle East | 0 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 20 | |||

| Asia (Including China) | 177 | 38 | 80 | 55 | 9 | 39 | 398 | Thailand: 43, Vietnam: 53, China: 178 | ||

| China | 68 | 19 | 37 | 21 | 0 | 33 | 178 | |||

| Africa | 4 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 27 | |||

| Oceania | 11 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 16 | |||

| 2019 | Subtotal/Total | 267 | 155 | 156 | 159 | 17 | 89 | 843 | ||

| Regional | North America (Including USA) | 39 | 71 | 24 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 150 | USA: 139 | |

| USA | 30 | 71 | 22 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 139 | |||

| Middle and South America | 7 | 7 | 20 | 8 | 0 | 1 | 43 | |||

| Europe | 23 | 9 | 4 | 38 | 2 | 43 | 119 | |||

| Middle East | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 9 | |||

| Asia (Including China) | 186 | 59 | 96 | 103 | 12 | 34 | 398 | India: 58, Thailand: 48, Vietnam: 63, Taiwan: 42, China: 196 | ||

| China | 69 | 35 | 33 | 39 | 3 | 17 | 196 | |||

| Africa | 3 | 4 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21 | |||

| Oceania | 8 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 16 | |||

| Subtotal/Total | 205 | 123 | 126 | 114 | 12 | 73 | 653 | |||

| 2020 | Regional | North America (Including USA) | 34 | 61 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 107 | USA: 97 |

| USA | 28 | 60 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 97 | |||

| Middle and South America | 5 | 5 | 23 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 42 | |||

| Europe | 25 | 10 | 8 | 22 | 3 | 16 | 84 | |||

| Middle East | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 9 | |||

| Asia (Including China) | 135 | 40 | 86 | 71 | 5 | 53 | 390 | Thailand: 39, Vienam: 70, China: 158 | ||

| China | 45 | 19 | 43 | 23 | 0 | 28 | 158 | |||

| Africa | 2 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | |||

| Oceania | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 12 | |||

| FY | Area | Related Laws | Total/Subtotal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Food Sanitation Law | Food Labeling Law | ||||

| 2018 | Subtotal/Total | 44 | 19 | 63 | |

| Reginal | North America | 4 | 4 | 8 | |

| Middle and South America | 4 | 1 | 5 | ||

| Europe | 16 | 6 | 22 | ||

| Middle East | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Asia | 18 | 6 | 24 | ||

| Africa | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Oceania | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| 2019 | Subtotal/Total | 58 | 15 | 73 | |

| Reginal | North America | 9 | 7 | 16 | |

| Middle and South America | 4 | 2 | 6 | ||

| Europe | 9 | 3 | 12 | ||

| Middle East | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Asia | 33 | 2 | 35 | ||

| Africa | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Oceania | 3 | 1 | 4 | ||

| 2020 | Subtotal/Total | 47 | 8 | 55 | |

| Reginal | North America | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Middle and South America | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Europe | 15 | 4 | 19 | ||

| Middle East | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Asia | 27 | 2 | 29 | ||

| Africa | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| Oceania | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Classification and Related Laws | Reason for Recall | Number of Occurrences | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FY2018 | FY2019 | FY2020 | ||

| a. Food Sanitation Law | a1. Foreign material contamination (dangerous foreign material, others) | 10 | 7 | 4 |

| a2. Pesticide residues, synthetic antibacterial agents, antibiotics (derived from raw materials) | 11 | 28 | 17 | |

| a3. Microbial contamination (food poisoning bacteria, others) | 11 | 2 | 13 | |

| a4. Violation of food additive use standards | 11 | 14 | 11 | |

| a5. Other (cross-contamination of allergens, etc.) | 1 | 7 | 2 | |

| b. Food Labeling Law | b1. Best-before date: No mistake | 11 | 8 | 4 |

| b2. Wrong allergen labeling | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| b3. Wrong labeling (wrong origin labeling, wrong labeling, wrong food additive labeling) | 5 | 4 | 1 | |

| Total | 63 | 73 | 55 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Matsumoto, T. Domestic and Imported Food Product Recalls in Japan: Trend Analysis and Preventive Measures. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7863. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137863

Matsumoto T. Domestic and Imported Food Product Recalls in Japan: Trend Analysis and Preventive Measures. Sustainability. 2022; 14(13):7863. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137863

Chicago/Turabian StyleMatsumoto, Takashi. 2022. "Domestic and Imported Food Product Recalls in Japan: Trend Analysis and Preventive Measures" Sustainability 14, no. 13: 7863. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137863

APA StyleMatsumoto, T. (2022). Domestic and Imported Food Product Recalls in Japan: Trend Analysis and Preventive Measures. Sustainability, 14(13), 7863. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137863