Drivers of Livelihood Strategies: Evidence from Mexico’s Indigenous Rural Households

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Determinants of Livelihood Strategies in Rural Households

2.2. Livelihood Strategies of Indigenous Households in Mexico

3. Methodological Approach

3.1. Conceptual Framework

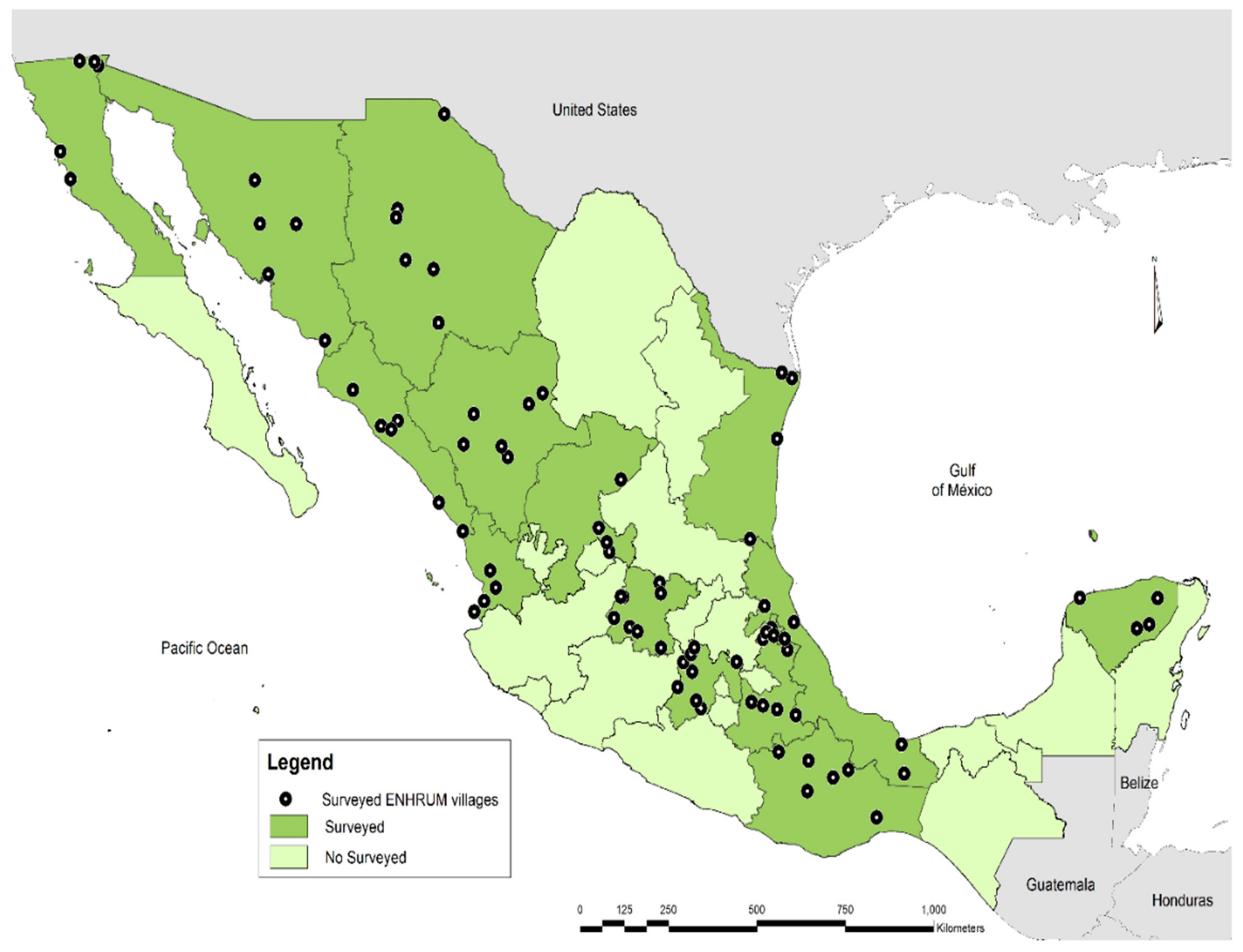

3.2. Data Source

3.3. Empirical Strategy

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics: Contrasts in Indigenous Rural Households

4.2. Econometric Findings: Determinants of Livelihood Strategies of Indigenous Rural Households

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Bank. Indigenous Peoples Overview. 2020. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/indigenouspeoples (accessed on 11 May 2020).

- Yörük, E.; Öker, İ.; Şarlak, L. Indigenous unrest and the contentious politics of social assistance in Mexico. World Dev. 2019, 123, 104618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Indigenous Latin America in the Twenty-First Century: The First Decade. Washington, D.C. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/23751 (accessed on 22 May 2020).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Censo de Población y Vivienda. 2020. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2020/ (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política Pública de Desarrollo Social (CONEVAL). La Pobreza en la Población Indígena de México, 2008–2018. Available online: https://www.coneval.org.mx/Medicion/MP/Documents/Pobreza_Poblacion_indigena_2008-2018.pdf#search=pobreza%20ind%C3%ADgena (accessed on 10 February 2020).

- Desmet, K.; Gomes, J.F.; Ortuño-Ortín, I. The geography of linguistic diversity and the provision of public goods. J. Dev. Econ. 2020, 143, 102384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Informe sobre Desarrollo sobre los Pueblos Indígenas de México: El Reto de la Igualdad de Oportunidades. 2010. Available online: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/mexico_nhdr_2010.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2020).

- Natarajan, N.; Newsham, A.; Rigg, J.; Suhardiman, D. A sustainable livelihoods framework for the 21st century. World Dev. 2022, 155, 105898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jezeer, R.E.; Verweij, P.A.; Boot, R.G.; Junginger, M.; Santos, M.J. Influence of livelihood assets, experienced shocks and perceived risks on smallholder coffee farming practices in Peru. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 242, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereda, V. Why Global North criminology fails to explain organized crime in Mexico. Theor. Criminol. 2022, 13624806221104562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, J.S.; Martinez-Alvarez, C.B. Diversifying violence: Mining, export-agriculture, and criminal governance in Mexico. World Dev. 2022, 151, 105769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rocio Valdivia, F.; Okowí, J. Drug trafficking in the Tarahumara region, northern Mexico: An analysis of racism and dispossession. World Dev. 2021, 142, 105426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, Y.; Andersen, P. Rural livelihood diversification and household well-being: Insights from Humla, Nepal. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 44, 239–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). AR5 Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Annex II: Glossary; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, F.; Freeman, H. Rural livelihoods and poverty reduction strategies in four African countries. J. Dev. 2004, 40, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, O.; Rayamajhi, S.; Uberhuaga, P.; Meilby, H.; Smith-Hall, C. Quantifying rural livelihood strategies in developing countries using an activity choice approach. Agric. Econ. 2013, 44, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choithani, C.; van Duijne, R.J.; Nijman, J. Changing livelihoods at India’s rural–urban transition. World Dev. 2021, 146, 105617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Ahmed, T. Farmers’ Livelihood Capital and Its Impact on Sustainable Livelihood Strategies: Evidence from the Poverty-Stricken Areas of Southwest China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschakert, P.; Coomes, O.T.; Potvin, C. Indigenous livelihoods, slash-and-burn agriculture, and carbon stocks in Eastern Panama. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 60, 807–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musumba, M.; Palm, C.A.; Komarek, A.M.; Mutuo, P.K.; Kaya, B. Household livelihood diversification in rural Africa. Agric. Econ. 2022, 53, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacconi, F.; Waha, K.; Ojeda, J.J.; Leith, P. Drivers and constraints of on-farm diversity. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 42, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila-Foucat, V.S.; Revollo-Fernández, D.; Navarrete, C. Determinants of Livelihood Diversification: The Case of Community-Based Ecotourism in Oaxaca, Mexico. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, M.M.; Kari, F.; Yahaya, S.R.B.; Al-Amin, A.Q. Livelihood assets and vulnerability context of marine park community development in Malaysia. Soc. Indic Res. 2016, 125, 771–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seid, M.; Simane, B.; Teferi, E.; Azmeraw, A. Determinants of farmers’ multiple-choice and sustainable use of indigenous land management practices in the Southern Rift Valley of Ethiopia. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2022, 4, 100158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotny, I.P.; Fuentes-Ponce, M.H.; Lopez-Ridaura, S.; Tittonell, P.; Rossing, W.A. Longitudinal analysis of household types and livelihood trajectories in Oaxaca, Mexico. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 81, 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alobo, S.A. Household livelihood diversification and gender: Panel evidence from rural Kenya. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 69, 156–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.H.E.; Polsky, C. Indexing livelihood vulnerability to the effects of typhoons in indigenous communities in Taiwan. Geogr. J. 2016, 182, 135–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komey, G.K. The denied land rights of the indigenous peoples and their endangered livelihood and survival: The case of the Nuba of the Sudan. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2008, 31, 991–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Robayo, K.J.; Méndez-López, M.E.; Molina-Villegas, A.; Juárez, L. What do we talk about when we talk about milpa? A conceptual approach to the significance, topics of research and impact of the mayan milpa system. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 77, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Janvry, A.; Sadoulet, E. Income strategies among rural households in Mexico: The role of off-farm activities. World Dev. 2001, 29, 467–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, C.B.; Reardon, T.; Webb, P. Nonfarm income diversification and household livelihood strategies in rural Africa: Concepts, dynamics, and policy implications. Food Policy 2001, 26, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yúnez-Naude, A.; Taylor, E. The determinants of nonfarm activities and incomes of rural households in Mexico, with emphasis on education. World Dev. 2001, 29, 561–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeman, Y.B.; Yeboah, A.O.; Ashie, E. Protected areas and poverty reduction: The role of ecotourism livelihood in local communities in Ghana. Community Dev. 2019, 50, 73–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, A.; Eakin, H.; Sweeney, S. Understanding peri-urban maize production through an examination of household livelihoods in the Toluca Metropolitan Area, Mexico. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 30, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasco, C.; Bilsborrow, R.; Torres, B. Income diversification of migrant colonists vs. indigenous populations: Contrasting strategies in the Amazon. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderzén, J.; Luna, A.G.; Luna-González, D.V.; Merrill, S.C.; Caswell, M.; Méndez, V.E.; Jonapá, R. Effects of on-farm diversification strategies on smallholder coffee farmer food security and income sufficiency in Chiapas, Mexico. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 77, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centro de Estudios para el Desarrollo Rural Sustentable y la Soberani Alimentaria (CEDRSSA). Los Indígenas en México: Población y Producción Rural; LXII Legislatura, Cámara de Diputados; Centro de Estudios para el Desarrollo Rural Sustentable y la Soberani Alimentaria (CEDRSSA): Ciudad de México, México, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean [ECLAC]. Estadísticas e Indicadores. Población en Situación de Pobreza Extrema y Pobreza Según Área Geográfica. Available online: https://cepalstatprod.cepal.org/cepalstat/tabulador/ConsultaIntegrada.asp?idIndicador=3328&idioma=e (accessed on 5 April 2020).

- Canedo, A.P. Analyzing Multidimensional Poverty Estimates in Mexico from an Ethnic Perspective: A Policy Tool for Bridging the Indigenous Gap. Poverty Public Policy 2018, 10, 543–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weltin, M.; Zasada, I.; Franke, C.; Piorr, A.; Raggi, M.; Viaggi, D. Analysing behavioural differences of farm households: An example of income diversification strategies based on european farm survey data. Land Use Policy 2017, 62, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, P. Rural livelihood change? Household capital, community resources and livelihood transition. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 32, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, X.; Pouliot, M.; Walelign, S.Z. Livelihood strategies and dynamics in rural Cambodia. World Dev. 2017, 97, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, A.; Speranza, C.; Roden, P.; Kiteme, B.; Wiesmann, U.; Nusser, M. Small-scale farming in semi-arid areas: Livelihood dynamics between 1997 and 2010 in Laikipia, Kenya. J. Rural Stud. 2012, 28, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, D.N. (Ed.) The Indigenous World; The International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de los Pueblos Indígenas (INPI). Indicadores Socioeconómicos de los Pueblos Indígenas de México. Available online: https://www.gob.mx/inpi/articulos/indicadores-socioeconomicos-de-los-pueblos-indigenas-de-mexico-2015-116128 (accessed on 19 May 2020).

- Saifullah, M.K.; Kari, F.B.; Othman, A. Income dependency on non-timber forest products: An empirical evidence of the indigenous people in Peninsular Malaysia. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 135, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Rivera, J.; Fierros-González, I. Determinants of indigenous migration: The case of Guerrero’s Mountain Region in Mexico. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2020, 21, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackleton, C.M.; Drescher, A.; Schlesinger, J. Urbanisation reshapes gendered engagement in land-based livelihood activities in mid-sized African towns. World Dev. 2020, 130, 104946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenewald, S.F.; Bulte, E. Trust and livelihood adaptation: Evidence from rural Mexico. Agric. Hum. Values 2013, 30, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, N.; Gauthier, R.; Mizrahi, A. Rural poverty in Mexico: Assets and livelihood strategies among the Mayas of Yucatan. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2007, 5, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Robles, E. Los Múltiples Rostros de la Pobreza en una Comunidad Maya de la Península de Yucatán. Estud. Soc. 2010, 18, 100–133. [Google Scholar]

- Robles, E.; Flechter, T. Qualitative Study of Perceptions on Poverty and Present Status of Assets in a Mayan Community in the Yucatan Peninsula. Univ. Cienc. 2008, 24, 191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Baffoe, G.; Matsuda, H. Why do rural communities do what they do in the context of livelihood activities? Exploring the livelihood priority and viability nexus. Community Dev. 2017, 48, 715–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diniz, F.; Hoogstra-Klein, M.; Kok, K.; Arts, B. Livelihood strategies in settlement projects in the Brazilian Amazon: Determining drivers and factors within the Agrarian Reform Program. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 32, 196–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Mills, B.F. Weather shocks, coping strategies, and consumption dynamics in rural Ethiopia. World Dev. 2018, 101, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Härtl, F.H.; Paul, C.; Knoke, T. Cropping systems are homogenized by off-farm income–Empirical evidence from small-scale farming systems in dry forests of southern Ecuador. Land Use Policy 2019, 82, 204–219. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R., Jr.; Cuecuecha, A. Remittances, household expenditure and investment in Guatemala. World Dev. 2010, 38, 1626–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Feldman, A. Shocks, income and wealth: Do they affect the extraction of natural Resources by rural households? World Dev. 2014, 64, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, T.; Berdegué, J.; Escobar, G. Rural nonfarm employment and incomes in Latin America: Overview and policy implications. World Dev. 2001, 29, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI). Encuesta Nacional de Ingresos y Gastos de los Hogares. Módulo de Condiciones Socioeconómicas: Glosario. 2014. Available online: https://www.inegi.org.mx/app/glosario/default.html?p=ENIGH2014 (accessed on 22 April 2020).

- Castañeda-Navarrete, J. Homegarden diversity and food security in southern Mexico. Food Secur. 2021, 13, 669–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lay, J.; Mahmoud, T.O.; M’Mukaria, G.M. Few opportunities, much desperation: The dichotomy of non-agricultural activities and inequality in Western Kenya. World Dev. 2018, 36, 2713–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, B.; Günter, S.; Acevedo-Cabra, R.; Knoke, T. Livelihood strategies, ethnicity and rural income: The case of migrant settlers and indigenous populations in the Ecuadorian Amazon. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 86, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salemink, K.; Strijker, D.; Bosworth, G. Rural development in the digital age: A systematic literature review on unequal ICT availabil-ity, adoption, and use in rural areas. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 54, 360–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, X.; Vélez, M.A.; Cárdenas, J.C.; Perdomo, N.; Matajira, C. Collective Property Leads to Household Investments: Lessons from Land Titling in Afro-Colombian Communities. World Dev. 2017, 97, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Metrics |

|---|---|

| Net annual income | Annual net income (MXN 2007) |

| Physical features of the house and housing services | |

| Rooms | Total number of rooms in a house |

| Wood or sheet metal walls | Walls in the house (1 = wood or sheet metal walls; 0 = otherwise) |

| Concrete roof | Composition of the roof of the house (1 = concrete roofs; 0 = otherwise) |

| Latrines for bathrooms | Type of bathrooms in the house (1 = latrines; 0 = otherwise) |

| Landline | House has access to a landline (1 = landline; 0 = otherwise) |

| Use of wood for cooking | House uses wood for cooking (1 = uses wood for cooking; 0 = otherwise) |

| Homes without a refrigerator | House without a refrigerator (1 = with a refrigerator; 0 = otherwise) |

| Characteristics of the household head | |

| Age | Age of household head (in years) |

| Years of schooling | Years of schooling of the household head |

| Characteristics of the household | |

| Hh size | Total number of people living in the household |

| Hh labor size (members aged 11 to 65 years) | The average number of members aged 11 to 65 years |

| Years of schooling of workers in the Hh | The average number of years of schooling completed by household members aged 11 to 65 years |

| Household owns farmland | Household has access to owned farmland (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise) |

| Household income activities | |

| Households with income from non-farming wages | Paid non-farming activities (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise) |

| Households with income from agricultural wages | Paid agricultural activities (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise) |

| Households that depend on self-employment | Self-employment activities (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise) |

| Households with livestock holdings | Livestock holdings (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise) |

| Households that use natural resources | Use and collection of natural resources (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise) |

| Households that participate in crop production | Crop production (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise) |

| Sources of external income: public and private | |

| Households with PROCAMPO | Household receives government cash transfers from PROCAMPO (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise) |

| Households with OPORTUNIDADES a | Household receives government cash transfers from OPORTUNIDADES (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise) |

| Households with domestic remittances | The household receives domestic remittances (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise) |

| Households with remittances from the United States | The household receives US remittances (1 = yes; 0 = otherwise) |

| Market access and transaction | |

| Distance to large urban centers | Average distance from the village to main population centers (km) |

| Available credit | Annual formal or informal credit available (MXN 2007) |

| Vulnerability to extreme events | |

| Index of damage due to climate-related events | Level of exposure to extreme events that cause loss of family agricultural assets (droughts, freezes, hailstorms, and strong winds) (percentage) |

| Livelihood Strategies of Indigenous Households | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Total (n = 286) | Group 1: SF (n = 91) | Group 2: NOFI (n = 102) | Group 3: OFI (n = 93) | ||||

| mean | sd | mean | sd | mean | sd | mean | sd | |

| Net annual income (MXN) | 34,045.3 | 3316.4 | 9821.1 | 8971.3 | 23,857.0 | 10,235.5 | 68,922.9 | 35,467.5 |

| Physical features of the house and housing services | ||||||||

| Number of rooms | 2.49 | 1.41 | 2.40 | 1.30 | 2.37 | 1.45 | 2.72 | 1.44 |

| Wood or sheet metal walls (%) | 0.46 | 0.49 | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.31 | 0.46 |

| Concrete roof (%) | 0.29 | 0.45 | 0.21 | 0.41 | 0.22 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.49 |

| Latrines for bathrooms (%) | 0.53 | 0.49 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.56 | 0.49 | 0.45 | 0.50 |

| Landline (%) | 0.19 | 0.39 | 0.14 | 0.35 | 0.21 | 0.41 | 0.22 | 0.42 |

| Use of wood for cooking (%) | 0.71 | 0.45 | 0.80 | 0.40 | 0.72 | 0.44 | 0.61 | 0.48 |

| Homes with refrigerator (%) | 0.44 | 0.49 | 0.31 | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.49 | 0.56 | 0.49 |

| Characteristics of the household head | ||||||||

| Age | 52.28 | 13.79 | 53.73 | 15.66 | 50.98 | 13.56 | 52.29 | 11.95 |

| Years of schooling | 3.76 | 3.35 | 3.54 | 2.83 | 3.54 | 2.92 | 4.22 | 4.16 |

| Characteristics of the household (Hh) | ||||||||

| Household owns farmland | 0.65 | 0.47 | 0.83 | 0.37 | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.52 | 0.50 |

| Hh labor (members aged 11 to 65 years) | 3.19 | 1.99 | 2.68 | 2.04 | 3.00 | 1.79 | 3.90 | 1.95 |

| Years of schooling of workers in the Hh (%) | 5.85 | 2.91 | 4.73 | 2.88 | 5.76 | 2.87 | 7.03 | 2.56 |

| Land size (has) | 4.97 | 8.58 | 4.64 | 7.27 | 4.80 | 7.67 | 5.49 | 10.54 |

| Household income activities | ||||||||

| Non-farming wages (%) | 0.20 | 0.40 | 0.06 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.35 | 0.41 | 0.49 |

| Agricultural wages (%) | 0.37 | 0.48 | 0.10 | 0.31 | 0.57 | 0.49 | 0.40 | 0.49 |

| Self-employment (%) | 0.22 | 0.41 | 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.16 | 0.37 | 0.32 | 0.46 |

| Livestock holdings (%) | 0.71 | 0.45 | 0.82 | 0.38 | 0.64 | 0.48 | 0.67 | 0.46 |

| Natural resources (%) | 0.71 | 0.45 | 0.75 | 0.43 | 0.76 | 0.42 | 0.62 | 0.48 |

| Crop production (%) | 0.70 | 0.45 | 0.84 | 0.36 | 0.69 | 0.46 | 0.58 | 0.49 |

| Sources of external income: public and private | ||||||||

| PROCAMPO (%) | 0.27 | 0.44 | 0.39 | 0.49 | 0.24 | 0.43 | 0.18 | 0.38 |

| OPORTUNIDADES (%) | 0.45 | 0.49 | 0.39 | 0.49 | 0.47 | 0.50 | 0.48 | 0.50 |

| Domestic remittances (%) | 0.25 | 0.43 | 0.21 | 0.41 | 0.23 | 0.42 | 0.30 | 0.46 |

| Remittances from the United States (%) | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.34 | 0.09 | 0.29 |

| Market access and transaction costs | ||||||||

| Distance to large urban centers (km) | 35.49 | 30.81 | 36.65 | 30.99 | 28.66 | 26.74 | 41.84 | 33.49 |

| Available credit (MXN) | 1157.34 | 4396.76 | 631.86 | 2525.24 | 969.60 | 2749.21 | 1877.41 | 6671.86 |

| Vulnerability to extreme events | ||||||||

| Index of damage due to climate-related events | 58.57 | 33.91 | 62.27 | 31.36 | 55.76 | 34.86 | 58.037 | 35.26 |

| Variable | Group 2: NOFI (102) | Group 3: OFI (n = 93) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RRR a | SE b | RRR | SE | |

| [1] | [2] | [3] | [4] | |

| Characteristics of the household head | ||||

| Young household head (ages 20 to 39 years) | 1.294955 | 1.224632 | 1.27201 | 1.294919 |

| Adult household head (ages 40 to 59 years) | 0.502201 | 0.215717 | 0.733889 | 0.354871 |

| Elderly household head (60+ years) | 0.604705 | 0.252713 | 0.996930 | 0.456288 |

| Household head with elementary education or less | 0.817247 | 0.505156 | 0.483710 | 0.303184 |

| Household characteristics | ||||

| Hh labor (ages 11 to 65 years) | 0.988807 | 0.100512 | 1.29548 *** | 0.137978 |

| Years of schooling of family workforce | 1.112587 | 0.075959 | 1.312143 *** | 0.102391 |

| Migratory networks | ||||

| Domestic remittances | 1.000115 ** | 0.000058 | 1.000163 *** | 0.000058 |

| International remittances | 1.000131 | 0.000087 | 1.000153 * | 0.000088 |

| Natural capital | ||||

| Household owns farmland | 1.241310 *** | 0.009222 | 1.155966 *** | 0.0064879 |

| Variables concerning vulnerability | ||||

| Community is in a municipal seat | 4.895737 *** | 2.66565 | 2.608106 | 1.716892 |

| Index of damage due to climate-related events | 0.987904 ** | 0.005790 | 0.993192 | 0.006151 |

| Homes with a landline | 2.095503 * | 0.936347 | 1.872148 | 0.913273 |

| Constant | 3.504708 | 3.058766 | 0.456084 | 0.446725 |

| Log likelihood | −255.2348 | |||

| Chi-square | 117.22 | |||

| Prob > chi-square | 0.0000 | |||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.1868 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fierros-González, I.; Mora-Rivera, J. Drivers of Livelihood Strategies: Evidence from Mexico’s Indigenous Rural Households. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137994

Fierros-González I, Mora-Rivera J. Drivers of Livelihood Strategies: Evidence from Mexico’s Indigenous Rural Households. Sustainability. 2022; 14(13):7994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137994

Chicago/Turabian StyleFierros-González, Isael, and Jorge Mora-Rivera. 2022. "Drivers of Livelihood Strategies: Evidence from Mexico’s Indigenous Rural Households" Sustainability 14, no. 13: 7994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137994

APA StyleFierros-González, I., & Mora-Rivera, J. (2022). Drivers of Livelihood Strategies: Evidence from Mexico’s Indigenous Rural Households. Sustainability, 14(13), 7994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14137994