Creating Food Value Chain Transformations through Regional Food Hubs: A Review Article

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: How many publications are there on growth-related FVCs that contribute towards developing the RFH business model?

- RQ2: What research methodologies are used on FVC and RFH studies?

- RQ3: What is the research gap with regard to the transformation of FVCs and RFHs?

2. Systematic Literature Review

2.1. Identification of Study

((“agr* value chain*” OR “food value chain*” OR “local food value chain*” OR “alternative food value chain*” OR “food hub*” OR “local food hub*” OR “regional food hub*” OR “local agr* food hub*”) AND (“business model” OR “food business model” AND “value chain* analysis”))

2.2. Selection of Study

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

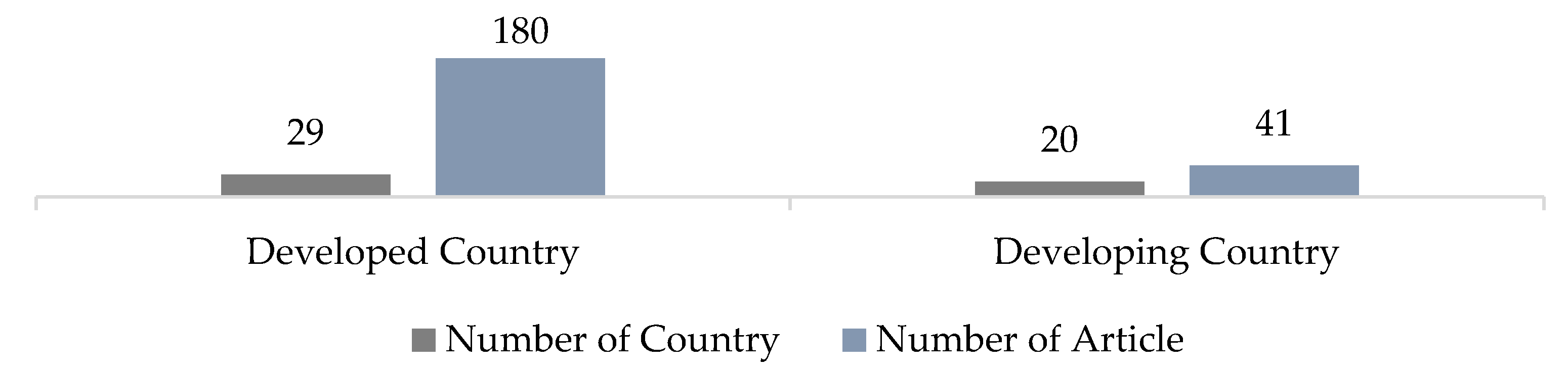

3.1. The Number of Publications on Growth-Related Food Value Chains and Regional Food Hubs

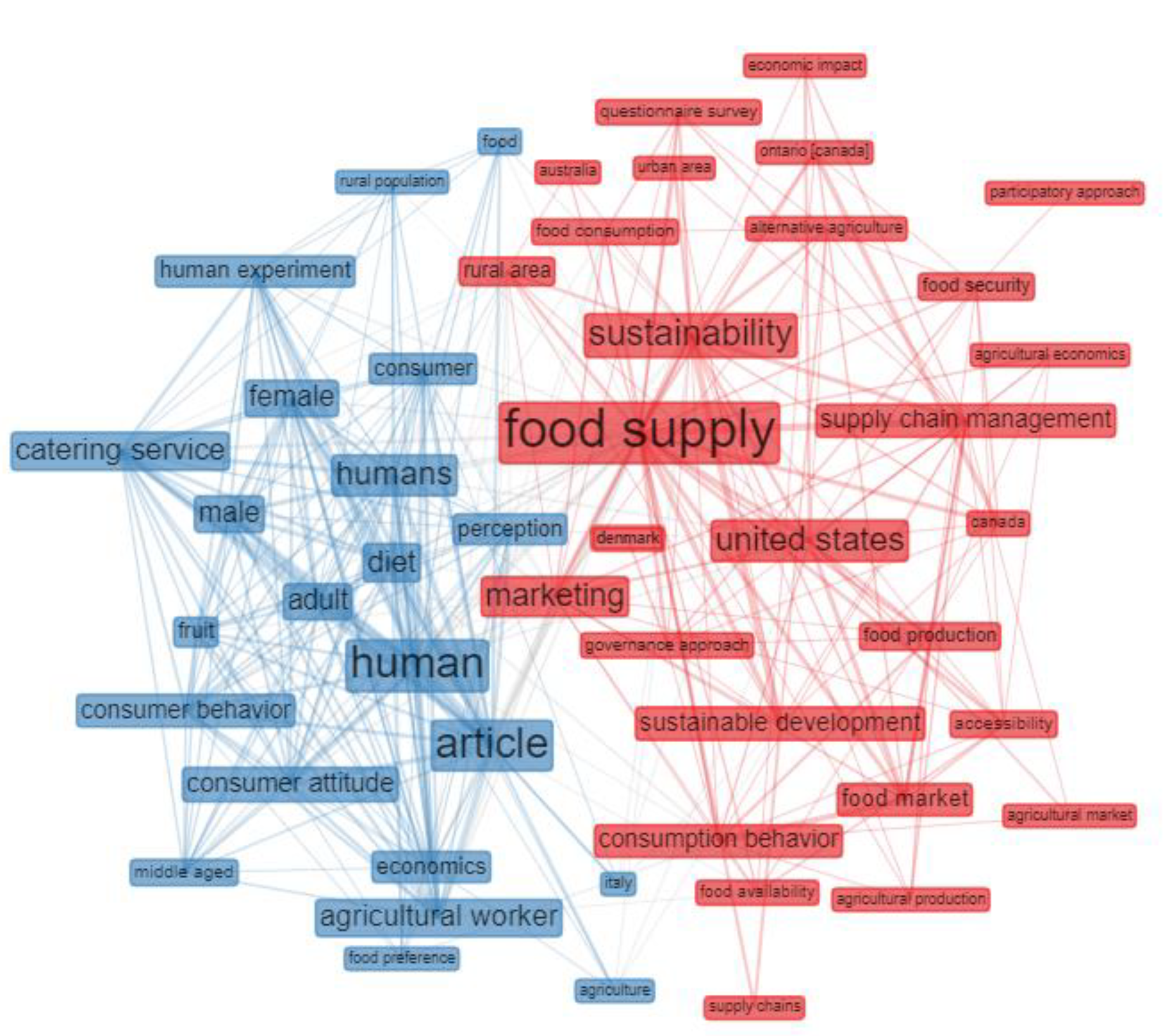

3.2. Overview of Food Value Chains and Regional Food Hubs Based on the Bibliometric Analysis

- Fundamental themes are divided into the high centrality and low density categories. Fundamental topics are essential to the field of study and refer to general topics that cross different fields of study.

- Motor topics are divided into the high centrality and density categories. Motor topics are essential to the development of the field.

- Isolated or niche topics have well-developed internal connections or high densities. However, these topics are categorized as non-essential external links with low centrality, and their subject matter is of limited importance.

- Emerging or declining topics are characterized by low centrality and high density. Emerging topics are categorized as underdeveloped and marginal.

3.3. Analysis of Research Methodology Used in Food Value Chain and Regional Food Hub Studies

3.4. Food Value Chains and Their Relationship with Sustainable Local Agriculture

3.5. Definition of Regional Food Hubs through the Prespective of Sustainability

3.6. Designs, Functions, and Development of Sustainable Regional Food Hubs

| Function | Process Based on Value-Added | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Planning | - Determining the optimum location of RFHs | [47,97] |

| - Determining the uniqueness of the community to improve the value proposition | [47,97] | |

| Infrastructure | - Social involvement - Warehouse to conduct basic processing of food (washing, weighing, sorting, grading, labelling, packing, packaging, and storage) - Human resources management | [86,97,102,106,107,110] |

| Services | - Operation services - Producer services | [97,108,109] |

| - Marketing services | [18] | |

| - Community and environmental services | [106,110,111,112,115] | |

| Community Support | - Strategy to enhance farmers’ willingness to join RFHs through emphasizing profit margins, information, transparency, and social engagement | [19,29,50,102,106,113] |

3.7. Research Gap of Regional Food Hubs Based on Food Value Chain Perspectsive

- a.

- Regional Food Hub topics lack integration between the production, marketing, and support services

- b.

- The study of Regional Food Hubs lacks terms of environmental research on the sustainability aspect

- c.

- Studies on Regional Food Hubs Are Less Concerned with Social Business

- d.

- Regional Food Hubs studies rarely used simulation and mathematical models

3.8. Limitations of the Research and Future Research Direction

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Monastyrnaya, E.; Bris, G.Y.L.; Yannouc, B.; Petitd, G. A template for sustainable food value chains. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2017, 20, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Arslan, A.; Chowdhury, M.; Khan, Z.; Tarba, S.Y. Reimagining global food value chains through effective resilience to COVID-19 shocks and similar future events: A dynamic capability perspective. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petit, G.; Bris, G.Y.-L.; Eckert, C.; Liu, Y. Facilitating aligned co-decisions for more sustainable food value chains. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belton, B.; Rosen, L.; Middleton, L.; Gazali, S.; Mamun, A.; Shieh, J.; Noronha, H.S.; Dhar, G.; Ilyas, M.; Proce, C.; et al. COVID-19 impacts and adaptations in Asia and Africa’s aquatic food value chains. Mar. Policy 2021, 129, 104523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graef, F.; Sieber, S.; Mutabiza, K.; Asch, F.; Biesalski, H.K.; Bitegeko, J.; Bokelmann, W.; Bruentrup, M.; Dietrich, O.; Elly, N.; et al. Framework for participatory food security research in rural food value chains. Glob. Food Sec. 2014, 3, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.L.; Peng, W.; Soon, C.F.; Hassim, M.F.N.; Misbah, S.; Rahmat, Z.; Yong, W.T.L.; Sonne, C. COVID-19 pandemic in the lens of food safety and security. Environ. Res. 2021, 193, 110405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, K.; Rampal, J. The COVID-19 pandemic and food insecurity: A viewpoint on India. World Dev. 2020, 135, 105068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagurney, A. Optimization of supply chain networks with inclusion of labor: Applications to COVID-19 pandemic disruptions. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 235, 108080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charpin, R. The resurgence of nationalism and its implications for supply chain risk management. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2021, 52, 4–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drost, S.; van Wijk, J.; de Boer, D. Including conflict-affected youth in agri-food chains: Agribusiness in northern Uganda. Confl. Secur. Dev. 2014, 14, 125–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Liu, S.; Lopez, C.; Lu, H.; Elgueta, S.; Chen, H.; Boshkoska, B.M. Blockchain technology in agri-food value chain management: A synthesis of applications, challenges and future research directions. Comput. Ind. 2019, 109, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanco, M.; Nazzaro, C.; Lerro, M.; Marotta, G. Sustainable Collective Innovation in the Agri-Food Value Chain: The Case of the ‘Aureo’ Wheat Supply Chain. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahn, R.A.; Yehya, A.A.K.; Zurayk, R. Digitalization for Sustainable Agri-Food Systems: Potential, Status, and Risks for the MENA Region. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjaya, S.; Perdana, T. Logistics system model development on supply chain management of tomato commodities for structured market. Procedia Manuf. 2015, 4, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Tsakiridis, A.; O’Donoghue, C.; Hynes, S.; Kilcline, K. A comparison of environmental and economic sustainability across seafood and livestock product value chains. Mar. Policy 2020, 117, 103968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reardon, T. Urbanization and the quiet revolution in the midstream of agrifood value chains. In Handbook on Urban Food Security in the Global South; Edward Elgar Publishing: Camberley, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, J.; Meemken, E.M.; Mazariegos-Anastassiou, V.; Liu, J.; Kim, E.; Gómez, M.I.; Canning, P.; Barrett, C.B. Post-farmgate food value chains make up most of consumer food expenditures globally. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleveland, D.A.; Müller, N.M.; Tranovich, A.C.; Mazaroli, D.N.; Hinson, K. Local food hubs for alternative food systems: A case study from Santa Barbara County, California. J. Rural Stud. 2014, 35, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, G.; Mulligan, C. Competitiveness of small farms and innovative food supply chains: The role of food hubs in creating sustainable regional and local food systems. Sustainability 2016, 8, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blay-Palmer, A.; Landman, K.; Knezevic, I.; Hayhurst, R. Constructing resilient, transformative communities through sustainable ‘food hubs. Local Environ. 2013, 18, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, A.; Das, R.; De, P.K. Impact of COVID-19 in food supply chain: Disruptions and recovery strategy. Curr. Res. Behav. Sci. 2021, 2, 100017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Sharma, M. Digital technologies (DT) adoption in agri-food supply chains amidst COVID-19: An approach towards food security concerns in developing countries. J. Glob. Oper. Strateg. Sourc. 2021, 15, 262–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Elomri, A.; El Omri, A.; Kerbache, L.; Liu, H. The compounded effects of COVID-19 pandemic and desert locust outbreak on food security and food supply chain. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soysal, M.; Bloemhof-Ruwaard, J.M.; Meuwissen, M.P.M.; van der Vorst, J.G.A.J. A review on quantitative models for sustainable food logistics management. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2012, 3, 136–155. [Google Scholar]

- Rota, C.; Reynolds, N.; Zanasi, C. Sustainable food supply chains: The role of collaboration and sustainable relationships. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2013, 4, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Wahl, A.; Bull, B.Q. Mapping Research Topics and Theories in Private Regulation for Sustainability in Global Value Chains. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 585–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deller, S.C.; Lamie, D.; Stickel, M. Local foods systems and community economic development. Community Dev. 2017, 48, 612–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A.; Krejci, C.C.; Craven, T.J. Logistics best practices for regional food systems: A review. Sustainability 2018, 10, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manikas, I.; Malindretos, G.; Moschuris, S. A community-based Agro-Food Hub model for sustainable farming. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mac Clay, P.; Feeney, R. Analyzing agribusiness value chains: A literature review. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2019, 22, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stovold, E.; Beecher, D.; Foxlee, R.; Noel-Storr, A. Study flow diagrams in Cochrane systematic review updates: An adapted PRISMA flow diagram. Syst. Rev. 2014, 3, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panic, N.; Leoncini, E.; De Belvis, G.; Ricciardi, W.; Boccia, S. Evaluation of the endorsement of the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) statement on the quality of published systematic review and meta-analyses. PLoS ONE 2013, 12, e83138. [Google Scholar]

- Ellegaard, O.; Wallin, J.A. The bibliometric analysis of scholarly production: How great is the impact? Scientometrics 2015, 105, 1809–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J. Informetr. 2017, 4, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, M.J.; Chiclana, F.; Collop, A.; de Ona, J.; Herrera-Viedma, E. A bibliometric analysis of the intelligent transportation systems research based on science mapping. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2013, 15, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Small, H.G.; Koenig, M.E.D. Journal clustering using a bibliographic coupling method. Inf. Process. Manag. 1977, 13, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomé, A.M.T.; Scavarda, L.F.; Scavarda, A.J. Conducting systematic literature review in operations management. Prod. Plan. Control 2016, 27, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaei Chadegani, A.; Salehi, H.; Md Yunus, M.; Farhadi, H.; Fooladi, M.; Farhadi, M.; Ebrahim, N.A. A comparison between two main academic literature collections: Web of Science and Scopus databases. Asian Soc. Sci. 2013, 9, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, F.d.A.; Rodrigues, F.M. Growth trend of scientific literature on genetic improvement through the database Scopus. Scientometrics 2015, 105, 805–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utomo, D.S.; Onggo, B.S.; Eldridge, S. Applications of agent-based modelling and simulation in the agri-food supply chains. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 269, 794–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinnes, J. Literature on Terrorism and the Media (including the Internet) an Extensive Bibliography. Perspect. Terror. 2013, 7, 145–147. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfswinkel, J.F.; Furtmueller, E.; Wilderom, C.P.M. Using grounded theory as a method for rigorously reviewing literature. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2013, 22, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiskerke, J.S.C. On places lost and places regained: Reflections on the alternative food geography and sustainable regional development. Int. Plan. Stud. 2009, 14, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, R. Technical efficiency, technical change and demand for skills in Malaysian food-based industry. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 2009, 9, 504–515. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-70349625597&partnerID=40&md5=e95a6308b2a33e465939899ef77471e0 (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Noordin, N.; Noor, N.L.M.; Hashim, M.; Samicho, Z. Value chain of Halal certification system: A case of the Malaysia Halal industry. Eur. Mediterr. Conf. Inf. Syst. 2009, 2008, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Perdana, T.; Chaerani, D.; Achmad, A.L.H.; Hermiatin, F.R. Scenarios for handling the impact of COVID-19 based on food supply network through regional food hubs under uncertainty. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armenta-Medina, D.T.A.; Ramirez-delReal, D.; Villanueva-Vásquez, C.; Mejia-Aguirre, C. Trends on advanced information and communication technologies for improving agricultural productivities: A bibliometric analysis. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Corte, V.G.; Del Gaudio, S.F.; Sciarelli, F. Sustainable tourism in the open innovation realm: A bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, C.A.; Papavasiliou, F. Scale and affect in the local food movement. Food Cult. Soc. 2018, 21, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, V.; Tallontire, A. Battlefields of ideas: Changing narratives and power dynamics in private standards in global agricultural value chains. Agric. Human Values 2014, 31, 481–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonney, L.; Collins, R.; Miles, M.P.; Verreynne, M.L. A note on entrepreneurship as an alternative logic to address food security in the developing world. J. Dev. Entrep. 2013, 18, 1350016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morley, A. Procuring for change: An exploration of the innovation potential of sustainable food procurement. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, S. Collaborative institutional work to generate alternative food systems. Organization 2020, 27, 314–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehl, J.A. Growing for Sydney: Exploring the urban food system through farmers’ social networks. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennchen, B.; Pregernig, M. Organizing joint practices in urban food initiatives—A comparative analysis of gardening, cooking and eating together. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangnus, E.; van Westen, A.C.M. Roaming through the maze of maize in Northern Ghana. A systems approach to explore the long-term effects of a food security intervention. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihailović, B.; Jean, I.R.; Popović, V.; Radosavljević, K.; Krasavac, B.C.; Bradić-Martinović, A. Farm differentiation strategies and sustainable regional development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graef, F.; Uckert, G. Gender determines scientists’ sustainability assessments of food-securing upgrading strategies. Land Policy 2018, 79, 84–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, L.; Griffith, G. The cashew value chain in Mozambique: Analysis of performance and suggestions for improvement. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2017, 8, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beuchelt, T.D.; Zeller, M. The role of cooperative business models for the success of smallholder coffee certification in Nicaragua: A comparison of conventional, organic and Organic-Fairtrade certified cooperatives. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2013, 28, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resti, Y.; Baars, R.; Verschuur, M.; Duteurtre, G. The role of cooperative in the milk value chain in west bandung regency, West Java Province. Media Peternak. 2017, 40, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mnimbo, T.S.; Lyimo-Macha, J.; Urassa, J.K.; Mahoo, H.F.; Tumbo, S.D.; Graef, F. Influence of gender on roles, choices of crop types and value chain upgrading strategies in semi-arid and sub-humid Tanzania. Food Secur. 2017, 9, 1173–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwangi, V.; Owuor, S.; Kiteme, B.; Giger, M. Assessing Smallholder Farmer’s Participation in the Wheat Value Chain in North-West Mt. Kenya. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Rahman, R.; Rezai, G.; Mohamed, Z.; Shamsudin, M.N.; Sharifuddin, J. Malaysia as Global Halal Hub: OIC Food Manufacturers’ Perspective. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2013, 25 (Suppl. 1), 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charatsari, C.; Kitsios, F.; Lioutas, D.E. Short food supply chains: The link between participation and farmers’ competencies. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2020, 35, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revoredo-Giha, C.; Toma, L.; Akaichi, F. An analysis of the tax incidence of VAT to milk in Malawi. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, X.H.; Vu, T.V.; Le, K.D.; Jirakiattikul, S.; Techato, K. An analysis of the smallholder farmers’ cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) value chain through a gender perspective: The case of Dak Lak province, Vietnam. Cogent. Econ. Financ. 2019, 7, 1645632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Góngora Pérez, R.D.; Milán Sendra, M.J.; López-i-Gelats, F. Strategies and drivers determining the incorporation of young farmers into the livestock sector. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 78, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, K.; Godrich, S.; Murray, S.; Auckland, S.; Blekkenhorst, L.; Penrose, B.; Lo, J.; Devine, A. Definitions, sources and self-reported consumption of regionally grown fruits and vegetables in two regions of Australia. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godrich, S.; Kent, K.; Murray, S.; Auckland, S.; Lo, J.; Blekkenhorst, L.; Penrose, B.; Devine, A. Australian consumer perceptions of regionally grown fruits and vegetables: Importance, enablers, and barriers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Hara, J.K.; Lin, J. Population Density and Local Food Market Channels. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2020, 42, 477–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayele, A.; Erchafo, T.; Bashe, A.; Tesfayohannes, S. Value chain analysis of wheat in Duna district, Hadiya zone, Southern Ethiopia. Heliyon 2021, 7, e07597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarekegn, K.; Asado, A.; Gafaro, T.; Shitaye, Y. Value chain analysis of banana in Bench Maji and Sheka Zones of Southern Ethiopia. Cogent Food Agric. 2020, 6, 1785103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoa, A.X.; Techato, K.; Dong, L.K.; Vuong, V.T.; Sopin, J. Advancing smallholders’ sustainable livelihood through linkages among stakeholders in the cassava (Manihot Esculenta Crantz) value chain: The case of Dak Lak Province, Vietnam. Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2019, 17, 5193–5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, D.; Limpens, G.; Rifin, A.; Kusnadi, N. Inclusive productive value chains, an overview of Indonesia’s cocoa industry. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2019, 9, 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, D.S.; Harrington, H.; Heiss, S.; Berlin, L. How Can Food Hubs Best Serve Their Buyers? Perspectives from Vermont. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2020, 15, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitaker, M.; Kolodinsky, J.; Wang, W.; Chase, L.C.; Kim, J.V.S.; Smith, D.; Estrin, H.; Vlaanderen, Z.V.; Greco, L. Evaluation of farm fresh food boxes: A hybrid alternative food network market innovation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żmija, K.; Fortes, A.; Tia, M.N.; Šūmane, S.; Ayambila, S.N.; Żmija, D.; Satoła, Ł.; Sutherland, L.A. Small farming and generational renewal in the context of food security challenges. Glob. Food Sec. 2020, 26, 100412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nost, E. Scaling-up local foods: Commodity practice in community supported agriculture (CSA). J. Rural Stud. 2014, 34, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Goetz, S.; Canning, P.; Perez, A. Optimal locations of fresh produce aggregation facilities in the United States with scale economies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2018, 197, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemadnia, H.; Goetz, S.J.; Canning, P.; Tavallali, M.S. Optimal wholesale facilities location within the fruit and vegetables supply chain with bimodal transportation options: An LP-MIP heuristic approach. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 244, 648–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, R.; Goetz, S.J.; McFadden, D.T.; Ge, H. Excess competition among food hubs. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2019, 44, 141–163. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85067339256&partnerID=40&md5=1ba7f9d56275dda2cd27e678f77ce7f5 (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Ge, H.; Canning, P.; Goetz, S.; Perez, A. Effects of scale economies and production seasonality on optimal hub locations: The case of regional fresh produce aggregation. Agric. Econ. 2018, 49, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melkonyan, A.; Gruchmann, T.; Lohmar, F.; Kamath, V.; Spinler, S. Sustainability assessment of last-mile logistics and distribution strategies: The case of local food networks. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 228, 107746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A.; Krejci, C.C. A hybrid simulation modeling framework for regional food hubs. J. Simul. 2019, 13, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, J.; Todeva, E.; Armando, E.; Giglio, E. Global value chains, business networks, strategy, and international business: Convergences. Rev. Bras. Gest. Neg. 2019, 21, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feenstra, G.; Hardesty, S. Values-based supply chains as a strategy for supporting small and mid-scale producers in the United States. Agriculture 2016, 6, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, D.D.; Moritaka, M.; Liu, R.; Fukuda, S. Restructuring toward a modernized agro-food value chain through vertical integration and contract farming: The swine-to-pork industry in Vietnam. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2020, 10, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zylberberg, E. Bloom or bust? A global value chain approach to smallholder flower production in Kenya. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2013, 3, 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Sarkar, A.; Qian, L. Evaluating the impacts of smallholder farmer’s participation in modern agricultural value chain tactics for facilitating poverty alleviation—A case study of kiwifruit industry in shaanxi, china. Agriculture 2021, 11, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilelu, C.; Klerkx, L.; Omore, A.; Baltenweck, I.; Leeuwis, C.; Githinji, J. Value Chain Upgrading and the Inclusion of Smallholders in Markets: Reflections on Contributions of Multi-Stakeholder Processes in Dairy Development in Tanzania. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2017, 29, 1102–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kähkönen, A. Value net—A new business model for the food industry? Br. Food J. 2012, 114, 681–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjauw-Koen-Fa, A.R.; Blok, V.; Omta, O.S.W.F. Exploring the integration of business and CSR perspectives in smallholder souring: Black soybean in Indonesia and tomato in India. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2018, 8, 656–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamah, E.Y.; Attatsi, P.B.; Nyamah, E.Y.; Opoku, R.K. Agri-food value chain transparency and firm performance: The role of institutional quality. Prod. Manuf. Res. 2022, 10, 62–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graef, F.; Hernandez, L.E.A.; König, H.J.; Uckert, G.; Mnimbo, M.T. Systemising gender integration with rural stakeholders’ sustainability impact assessments: A case study with three low-input upgrading strategies. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2018, 68, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barham, J.; Tropp, D.; Enterline, K.; Farbman, J.; Fisk, J.; Kiraly, S. Regional Food Hub Resource Guide; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, L.O.; Jablonski, B.B.R.; O’Hara, J.K. School districts and their local food supply chains. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2019, 34, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, J.R.; Conner, D.; McRae, G.; Darby, H. Building resilience in nonprofit food hubs. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2014, 4, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejci, C.C.; Beamon, B.M. Modeling food supply chain sustainability using multi-agent simulation. Int. J. Soc. Sustain. Econ. Soc. Cult. Context 2013, 8, 143–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessari, M.; Joly, C.; Jaouen, A.; Jaeck, M. Alternative food networks: Good practices for sustainable performance. J. Mark. Manag. 2020, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avetisyan, T.; Brent Ross, R. The intersection of social and economic value creation in social entrepreneurship: A comparative case study of food hubs. J. Food Distrib. Res. 2019, 50, 97–104. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85071847507&partnerID=40&md5=1cb3b16c530ae0ef72acc85566302eba (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Motzer, N. ‘Broad but not deep’: Regional food hubs and rural development in the United States [‘Large mais pas esarrol’: Centres d’alimentation régionaux et développement rural aux Etats-Unis] [‘Amplio pero no profundo’: Centros esarroll de alimentos y esarrollo]. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2019, 20, 1138–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Pirog, R.; Hamm, M.W. Food Hubs: Definitions, Expectations, and Realities. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2015, 10, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejci, C.; Beamon, B. Impacts of farmer coordination decisions on food supply chain structure. JASSS 2015, 18, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Pirog, R.; Hamm, M.W. Predictors of Food Hub Financial Viability. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2015, 10, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonski, B.B.R.; Bauman, A.; Thilmany, D. Local food market orientation and labor intensity. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy 2021, 43, 916–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entsminger, J.S. Research report: Coordinating intermediaries and scaling up local and regional food systems: An organizational species approach to understanding the roles of food hubs. J. Food Distrib. Res. 2020, 51, 32–42. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85081232698&partnerID=40&md5=5532659d71bb0ec12259ee331ba493f9 (accessed on 18 August 2021).

- Le Velly, R.; Dufeu, I. Alternative food networks as ‘market agencements’: Exploring their multiple hybridities. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 43, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saulters, M.M.; Hendrickson, M.K.; Chaddad, F. Fairness in alternative food networks: An exploration with midwestern social entrepreneurs. Agric. Human Values 2018, 35, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickland, K.; Whitman, J.R. Beyond Food Distribution: The Context of Food Bank Innovation in Alabama. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2020, 15, 553–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batziakas, K.G.; Stanley, H.; Batziakas, A.G.; Brecht, J.K.; Rivard, C.L.; Pliakoni, E.D. Reducing postharvest food losses in organic spinach with the implementation of high tunnel production systems. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 40, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía, G.D.; Granados-Rivera, J.A.; Jarrín Castellanos, A.; Mayorquín, N.; Molano, E. Strategic supply chain planning for food hubs in central olombia: An approach for sustainable food supply and distribution. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mount, P.; Andrée, P. Visualising community-based food projects in Ontario. Local Environ. 2013, 18, 578–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, E.J.O.; Omondi, I.; Karimov, A.A.; Baltenweck, I. Dairy farm households, processor linkages and household income: The case of dairy hub linkages in East Africa. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2016, 19, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, J.; Franzel, S.; Cunha, M.; Gyau, A.; Mithöfer, D. Guides for value chain development: A comparative review. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2015, 5, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watabaji, M.D.; Molnar, A.; Dora, M.K.; Gellynck, X. The influence of value chain integration on performance: An empirical study of the malt barley value chain in Ethiopia. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2016, 19, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, V.; Nguyen, A.; Hubbard, C.; K.-Nguyen, D. Exploring the Governance and Fairness in the Milk Value Chain: A Case Study in Vietnam. Agriculture 2021, 11, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, Q.; Bellows, A.L.; McLaren, R.; Jones, A.D.; Fanzo, J. You say you want a data revolution? Taking on food systems accountability. Agriculture 2021, 11, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azani, M.; Shaerpour, M.; Yazdani, M.A.; Aghsami, A.; Jolai, F. A Novel Scenario-Based Bi-objective Optimization Model for Sustainable Food Supply Chain During the COVID-19: A Case Study. Process Integr. Optim. Sustain. 2022, 6, 139–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morganti, E.; Gonzalez-Feliu, J. City logistics for perishable products. The case of the Parma’s Food Hub. Case Stud. Transp. Policy 2015, 3, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggio, A.M.; Evans, J.R. Will Participatory Guarantee Systems Happen Here? The Case for Innovative Food Systems Governance in the Developed World. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummer, S.; Milestad, R. The diversity of organic box schemes in europe-an exploratory study in four countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mount, P.; Hazen, S.; Holmes, S.; Fraser, E.; Winson, A.; Knezevic, I.; Nelson, E.; Ohberg, L.; Andrée, P.; Landman, K. Barriers to the local food movement: Ontario’s community food projects and the capacity for convergence. Local Environ. 2013, 18, 592–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonski, B.B.R.; Schmit, T.M.; Kay, D. Assessing the economic impacts of food hubs on regional economies: A framework that includes opportunity cost. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2016, 45, 143–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, J.J.; Macken-Walsh, Á. Multi-actor social networks: A social practice approach to understanding food hubs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, G. Sustainable agri-food economies: Re-territorialising farming practices, markets, supply chains, and policies. Agriculture 2020, 10, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, P.; Taherzadeh, A. Working co-operatively for sustainable and just food system transformation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conner, D.S.; Sims, K.; Berkfield, R.; Harrington, H. Do farmers and other suppliers benefit from sales to food hubs? Evidence from Vermont. J. Hunger Environ. Nutr. 2018, 13, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroink, M.L.; Nelson, C.H. Complexity and food hubs: Five case studies from Northern Ontario. Local Environ. 2013, 18, 620–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballamingie, P.; Walker, S.M.L. Field of dreams: Just food’s proposal to create a community food and sustainable agriculture hub in Ottawa, Ontario. Local Environ. 2013, 18, 529–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, C.; Connolly, C. Aiding farm to school implementation: An assessment of facilitation mechanisms. Agric. Resour. Econ. Rev. 2022, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prost, S. Food democracy for all? Developing a food hub in the context of socio-economic deprivation. Polit. Gov. 2019, 7, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curry, N.R. The rural social economy, community food hubs and the market. Local Econ. 2021, 36, 569–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Author(s) | Content Analysis? (Y/N) | Article Time Span (Year) | Food Value Chain? (Y/N) | Regional Food Hub? (Y/N) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Soysal et al. (2012) | Y | 1987–2012 | Y | N | [24] |

| 2 | Rota et al. (2013) | Y | 1990–2012 | Y | N | [25] |

| 3 | Wahl and Bull (2014) | Y | 1999–2011 | Y | N | [26] |

| 4 | Berti and Mulligan (2016) | Y | - | N | Y | [19] |

| 5 | Deller et al. (2017) | Y | - | Y | Y | [27] |

| 6 | Mittal et al. (2018) | Y | 2006–2016 | N | Y | [28] |

| 7 | Manikas et al. (2019) | Y | - | N | Y | [29] |

| 8 | Clay and Feeney (2019) | Y | 1980–2017 | Y | N | [30] |

| 9 | This article | Y | 2009–2022 | Y | Y | - |

| Criteria | Decision | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| Sector | Agriculture and food sector only | This research is specific to developing food security through the RFH business model. |

| Scope | Food value chains, regional food hubs, and business models | This research focuses on developing food security to improve local agriculture’s value through developing the RFH business model. |

| Geographic location | Global | RFHs are widely used in developed countries such as the United States, European countries, and Mexico [19]. The global region can describe the strategies that can be used to overcome an entrepreneurship model for developing countries. |

| Nature of study | Empirical | Empirical cases were selected because the studies can offer extensive evidence of FVCs and business models. |

| Time limit | No limit | There is no time limit to receive information about FVCs and RFHs [42]. |

| Method | Quantitative and qualitative | Both quantitative and qualitative methods provide an empirical study of FVCs and RFHs. |

| Methods | Thematic Evolution | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Business | Food Hubs | Marketing | Sustainability | Food Value Chains | Grand Total | |

| Action Research | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Case Study | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Ethnographical | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Grounded Theory | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Integer Programming | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Mixed Methods | 1 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 11 | |

| Modelling | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Optimization | 4 | 4 | ||||

| Phenomenology | 5 | 10 | 2 | 3 | 12 | 32 |

| Simulation | 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

| Statistics | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 11 |

| Grand Total | 9 | 28 | 4 | 7 | 29 | 77 |

| Sustainability Category | Study Area | Topic of The Research | Food Value Chain | Sources | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production Activities | Marketing Activities | Support Services | ||||

| Economic | Regional | - Smallholder Competitiveness | √ | √ | √ | [58,60,64,74,75,91] |

| - Technology and Farming Innovativeness | √ | [53,73,92] | ||||

| - Management and Business Models | √ | √ | √ | [1,3,53,57,93,94] | ||

| - Financial Policy | √ | [67] | ||||

| Global | - Business Strategy | √ | √ | [90] | ||

| Social | Regional | - Institutional Analysis | √ | √ | √ | [53,54,76,89,95] |

| - Gender Issues | √ | √ | √ | [59,63,68,96] | ||

| Global | - Knowledge and Capacity Building | √ | √ | [51] | ||

| Environmental | Regional | - Improving Knowledge | √ | [88] | ||

| Approaches | Definition | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| Value-Based | An RFH refers to a local aggregator hub that connects local producers and markets, conceptualizing a value-based approach in the chain of activities. | [19,20,77] |

| Sustainable Strategy Development | An RFH is an innovative business strategy that attempts to empower local producers through social, environmental, and economic approaches, through collaboration with various parties in the food chain. | [47,53,65,81,84,99,101,105] |

| Social Entrepreneurial | An RFH is a social entrepreneur that enhances the capabilities and capacities of local producers to meet their customers’ need to in turn achieve the long-term competitiveness of local products. | [18,54,102,103,106] |

| Sustainability Category | Topic of the Research | Business Model | Food Value Chains | Source | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial | Social Business | Production Activities | Marketing Activities | Support Services | |||

| Economic | - Efficiency in Distribution | √ | √ | [72,98,120] | |||

| - Improving the Logistics Performance | √ | √ | [47,81,82,83,84,85,86,101,121] | ||||

| - Institutional Development | √ | √ | √ | [18,51,65,77,80,103,116,122,123,124] | |||

| - Improving the Capability of Marketing | √ | √ | √ | [70,71,78,115] | |||

| - Innovative Business Model | √ | √ | [79,113,125] | ||||

| - Financial Development | √ | √ | [106] | ||||

| - Collaboration Action | √ | √ | [126] | ||||

| Social | - Rural Community Development | √ | √ | √ | [19,55,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128] | ||

| - Institutional Development | √ | √ | √ | √ | [56,99,102,111,129,130,131,132,133,134] | ||

| Environmental | - Improving the Logistics Performance | √ | √ | [47,82,83,84,85,86,101,121] | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hermiatin, F.R.; Handayati, Y.; Perdana, T.; Wardhana, D. Creating Food Value Chain Transformations through Regional Food Hubs: A Review Article. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8196. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138196

Hermiatin FR, Handayati Y, Perdana T, Wardhana D. Creating Food Value Chain Transformations through Regional Food Hubs: A Review Article. Sustainability. 2022; 14(13):8196. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138196

Chicago/Turabian StyleHermiatin, Fernianda Rahayu, Yuanita Handayati, Tomy Perdana, and Dadan Wardhana. 2022. "Creating Food Value Chain Transformations through Regional Food Hubs: A Review Article" Sustainability 14, no. 13: 8196. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138196

APA StyleHermiatin, F. R., Handayati, Y., Perdana, T., & Wardhana, D. (2022). Creating Food Value Chain Transformations through Regional Food Hubs: A Review Article. Sustainability, 14(13), 8196. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138196