The Influence of Family Social Status on Farmer Entrepreneurship: Empirical Analysis Based on Thousand Villages Survey in China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

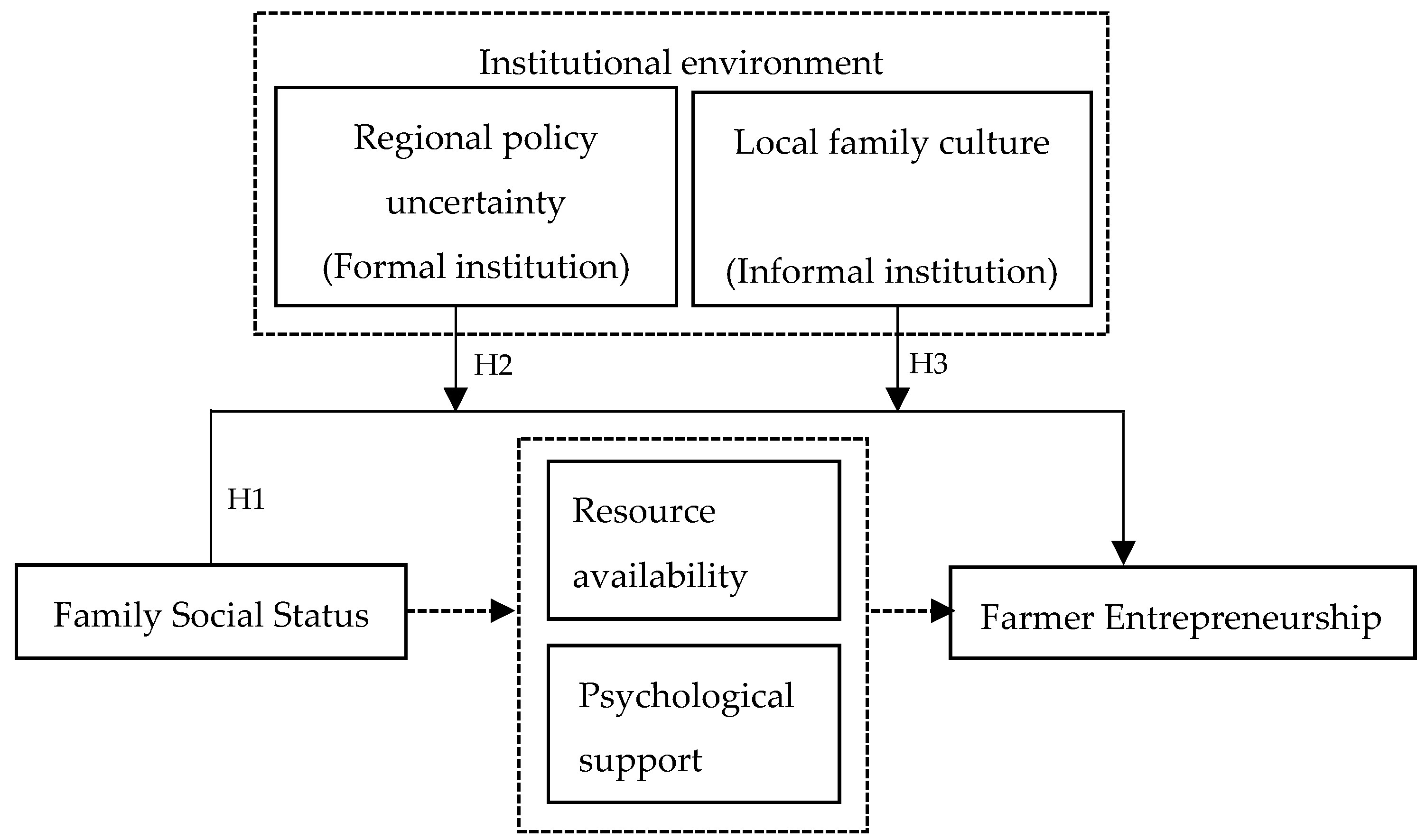

2. Theory and Hypothesis

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Family Social Status and Farmer Entrepreneurship

2.3. The Moderating Effect of Regional Policy Uncertainty

2.4. The Moderating Effect of Local Family Culture

3. Methods

3.1. Data and Sample

3.2. Measures

3.3. Empirical Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Logistic Regression Results

4.2. Propensity Score Matching Test

4.3. Instrumental Variable Regression

4.4. Heckman’s Two-Stage Test

4.5. Robustness Check

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Montalvo, J.G.; Ravallion, M. The pattern of growth and poverty reduction in China. J. Comp. Econ. 2010, 38, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mcelwee, G. Farmers as entrepreneurs: Developing competitive skills. J. Dev. Entrep. 2006, 11, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McElwee, G.; Robson, A. Diversifying the farm: Opportunities and barriers. Finn. J. Rural Res. Policy. 2005, 4, 84–96. [Google Scholar]

- Kłodziński, M. Factors affecting the development of rural entrepreneurship from the perspective of integration with the European Union. In Proceedings of the Międzynarodowa Konferencja Naukowa, Kraków, Poland, 11–12 January 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.Y.; Zhou, C.C.; Zhang, J.K. Does the synergy among agriculture, industry, and the service industry alleviate rural poverty? Evidence from China. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, P.; Talbot, H. Providing Advice and Information in Support of Rural Microbusinesses; Centre for Rural Economy Research Report, University of Newcastle: Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- McElwee, G. A segmentation framework for the farm sector. In Proceedings of the 3rd Rural Entrepreneurship Conference, Univesity of Paisley, Glasgow, UK, 9–19 October 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz, F.M. Evolving human resource management in Southern African multinational firms: Towards an Afro-Asian nexus. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Man. 2012, 23, 2938–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Seibert, S.E.; Lumpkin, G.T. The relationship of personality to entrepreneurial intentions and performance: A meta-analytic review. J. Manag. 2010, 36, 381–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasson, H.; Sok, J. Perceived obstacles for business development: Construct development and the impact of farmers’ personal values and personality profile in the Swedish agricultural context. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 81, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.Z.; Chen, M. Personality traits, entrepreneurial learning and entrepreneurial performance of farmers. Chin. Rural Econ. 2014, 10, 62–75. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, W.; Wu, M. Life-cycle factors and entrepreneurship: Evidence from rural China. Small Bus. Econ. 2021, 57, 2017–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, A.; Barber, D. The Gap in Transition Planning Education Opportunities for Rural Entrepreneurs. Amer. J. Entrep. 2020, 13, 92–125. [Google Scholar]

- Folmer, H.; Dutta, S.; Oud, H. Determinants of rural industrial entrepreneurship of farmers in west Bengal’s structural equations approach. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2010, 33, 367–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Bing, W.; Bai, G. Investigation on the success of peasant entrepreneurs. Phys. Procedia 2012, 25, 2282–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murphy, R. How Migrant Labor is Changing Rural China, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- George, G.; Kotha, R.; Parikh, P.; Alnuaimi, T.; Bahaj, A. Social structure, reasonable gain, and entrepreneurship in Africa. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 1118–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hu, M.; Su, Y.; Zhang, H. Migrant Entrepreneurship: The Family as Emotional Support, Social Capital and Human Capital. Emerg. Mark. Financ. Trade 2021, 57, 3367–3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrin, S.; Islam, N.; Ahmed, S.U. A Multivariate Model of Micro Credit and Rural Women Entrepreneurship Development in Bangladesh. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2008, 3, 169–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Xie, W.; Wang, T.; Zhao, X. Does digital inclusive finance promote coastal rural entrepreneurship? J. Coast. Res. 2020, 103, 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.; Dash, S. Constraints faced by entrepreneurs in developing countries: A review and assessment. World Rev. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Develop. 2014, 10, 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Huang, Y.; Huang, R.; Xie, G.; Cai, W. Factors Influencing Returning Migrants’ Entrepreneurship Intentions for Rural E-Commerce: An Empirical Investigation in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhou, J.X.; Wang, Y.; Xi, Y. Rural entrepreneurship in an emerging economy: Reading institutional perspectives from entrepreneur stories. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2013, 51, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, W.; Hu, M.; Wang, X. Does the Utilization of Information Communication Technology Promote Entrepreneurship: Evidence from Rural China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2019, 141, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hambrick, D.C.; Mason, P.A. Upper echelons: The organization as a reflection of its top managers. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1984, 9, 193–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.M.; Ali, S.R.; Soleck, G.; Hopps, J.; Dunston, K.; Pickett, J.T. Using Social Class in Counseling Psychology Research. J. Couns. Psychol. 2004, 51, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Blader, S.L. Why Does Social Class Affect Subjective Well-Being? The Role of Status and Power. Pers. Soc. Psychol. B. 2020, 46, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cote, S. How social class shapes thoughts and actions in organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 2011, 31, 43–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kish-Gephart, J.J.; Campbell, J. You don’t forget your roots: The influence of CEO social class background on strategic risk taking. Acad. Manag. J. 2015, 58, 1614–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kish-Gephart, J.J. Social class & risk preferences and behavior. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 18, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoncic, J.A.; Antoncic, B.; Gantar, M.; Hisrich, R.D.; Marks, L.J.; Bachkirov, A.A.; Li, Z.; Polzin, P.; Borges, J.L.; Coelho, A.; et al. Risk-Taking Propensity and Entrepreneurship: The Role of Power Distance. J. Enterp. Cult. 2018, 26, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, K.; Lee, Y.S. Risk Preferences and Immigration Attitudes: Evidence from Four East Asian Countries. Int. Migr. 2018, 56, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ye, J.M. Risk preference of top management team and the failure of technological innovation in firms–based on principal component analysis and probit regression. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2021, 40, 1161–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonin, H.; Dohmen, T.; Falk, A.; Huffman, D.; Sunde, U. Cross-sectional Earnings Risk and Occupational Sorting: The Role of Risk Attitudes. Labour Econ. 2007, 14, 926–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eckel, C.C.; Grossman, P.J. Forecasting Risk Attitudes: An Experimental Study Using Actual and Forecase Gamble Choices. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2008, 68, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, M.L.; Huettel, S.A. Risky Business: The neuroeconomics of Decision Making under Uncertainty. Nat. Neurosci. 2008, 11, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoncic, B. Risk taking in intrapreneurship: Translating the individual level risk aversion into the organizational risk taking. J. Enterp. Cult. 2003, 11, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisrich, R.D.; Peters, M.P. Entrepreneurship: Starting, Developing, and Managing a New Enterprise, 4th ed.; Irwin: Chicago, IL, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, M.W.; Piff, P.K.; Mendoza-Denton, R.; Rheinschmidt, M.L.; Keltner, D. Social class, solipsism, and contextualism: How the rich are different from the poor. Psychol. Rev. 2012, 119, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weiss, Y.; Fershtman, C. Social status and economic performance: A survey. Eur. Econ. Rev. 1998, 42, 801–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Raynard, M. Institutional Strategies in Emerging Markets. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2015, 9, 291–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D.C. What’s law got to do with it? Legal institutions and economic reform in China. UCLA Pac. Basin Law J. 1991, 10, 1–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litwack, J.M. Legality and market reform in Soviet-type economies. J. Econ. Perspect. 1991, 5, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eesley, C.; Li, J.B.; Yang, D. Does Institutional Change in Universities Influence High-Tech Entrepreneurship? Evidence from China’s Project 985. Organ. Sci. 2016, 27, 446–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hiatt, S.R.; Sine, W.D. Clear and present danger: Planning and new venture survival amid political and civil violence. Strateg. Manag. J. 2014, 35, 773–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yiu, D.W.; Hoskisson, R.E.; Bruton, G.D.; Lu, Y. Dueling Institutional Logics and The Effect on Strategic Entrepreneurship in Chinese Business Groups. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2014, 8, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Gustafsson, V. Nascent entrepreneurs in China: Social class identity, prior experience affiliation and identification of innovative opportunity: A study based on the Chinese Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics (CPSED) project. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2012, 6, 14–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.; Sampson, T.; Zia, B. Prices or knowledge? What drives demand for financial services in emerging markets? J. Financ. 2011, 66, 1933–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, A.; Unel, B. Do attitudes toward risk taking affect entrepreneurship? Evidence from second-generation Americans. J. Econ. Growth. 2021, 26, 385–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, J.W. The Rise of the Entrepreneur; Schocken Books: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.A. Cognitive Mechanisms in Entrepreneurship: Why and When Entrepreneurs Think Differently Than Other People. J. Bus. Ventur. 1998, 13, 275–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.P. Research on the risk categories and prevention paths in the migrant labors’ returning home to start business in agricultural field. Acad. J. Zhongzhou 2019, 4, 38–44. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, S.; Kiminami, L.; Furuzawa, S. Analysis on the factors affecting farmers’ performance in disaster risk management at community level: Focusing on a Haor locality in Bangladesh. Asia-Pac. J. Reg. Sci. 2020, 10, 737–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, R. How socio-economic and natural resource inequality impedes entrepreneurial ventures of farmers in rural India. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2019, 31, 433–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangogo, D.; Dentoni, D.; Bijman, J. Adoption of climate-smart agriculture among smallholder farmers: Does farmer entrepreneurship matter? Land Use Policy 2021, 109, 105666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, N.T.; Pabuayon, I.M.; Kien, N.D.; Dung, T.Q.; An, L.T.; Dinh, N.C. Factors driving the adoption of coping strategies to market risks of shrimp farmers: A case study in a coastal province of Vietnam. Asian J. Agr. Rural Dev. 2022, 12, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.F.; Luo, B.L. Research on farmer entrepreneurship: A Literature review. Manag. Res. 2014, 9, 187–208. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, D.H.; Li, S.R.; Lin, S.Y. The new theoretical paradigm of entrepreneurial research-complexity science theory. Entrep. Manag. Res. 2007, 1, 31–60. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Seibert, S.E.; Hills, G.E. The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, D.Y.; Tsang, E.W.K. The effects of entrepreneurial personality, background and network activities on venture growth. J. Manag. Stud. 2001, 38, 583–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, S.; Locke, E.A.; Collins, C.J. Entrepreneurial motivation. Hum. Resour. Manag. R. 2003, 13, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boyd, N.G.; Vozikis, G.S. The Influence of Self-Efficacy on the Development of Entrepreneurial Intentions and Actions. Entre. Theory Pract. 1994, 18, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.A. The cognitive perspective: A valuable tool for answering entrepreneurship’s basic “why” questions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2004, 19, 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, A.H.; Fry, F.L.; Stephens, P. The Influence of Role Models on Entrepreneurial Intentions. J. Dev. Entrep. 2006, 11, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhou, X.; Wang, D.N. The influence of social network on farmers’ entrepreneurship. J. Technol. Econ. 2016, 35, 78–83, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, M.D.M.F.; Arroyo, M.R.; Bojica, A.M.; Pérez, V.F. Prior knowledge and social networks in the exploitation of entrepreneurial opportunities. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2010, 6, 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuervo, A. Individual and Environmental Determinants of Entrepreneurship. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2005, 1, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, P.D.; Bygrave, W. Gobal Entrepreneurship Monitor: Executive Report; Babason College, London Business School: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.H. Forty Years of Reform and Opening up: Transformation and Prospect of Agricultural Industrial Organization in China. Agr. Econ. Issues 2018, 11, 61–69. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, W.H.; Li, M.J.; Li, J.B. Digital village empowerment and farmers’ income growth: Mechanism and empirical test—Research on the regulation effect based on Farmers’ entrepreneurial activity. J. Southeast Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci.) 2021, 23, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beugelsdijk, S. Entrepreneurial culture, regional innovativeness and economic growth. J. Evol. Econ. 2007, 17, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chatman, D.; Altman, I.; Johnson, T. Community Entrepreneurial Climate: An Analysis of Small Business Owners’ Perspectives in 12 Small Towns in Missouri, USA. J. Rural Community Dev. 2008, 3, 60–77. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, J.Y.; Guo, H.D. Entrepreneurial atmosphere, social network and entrepreneurial intention of farmers. China Rural Surv. 2012, 2, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.Y.; Sun, H.X.; Wang, W.Y. Summary and theoretical analysis framework of domestic migrant workers’ entrepreneurship. J. Shandong Univ. Tech. Bus. 2014, 28, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, W. Household resource endowment, entrepreneurial ability and willingness to adopt environment-friendly technology: From the perspective of family farm. Econ. Rev. 2016, 33, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Z.L.; Yang, Y.Y. Family endowment, migrant workers’ return and entrepreneurial participation: Empirical evidence from Enshi Prefecture, Hubei Province. Econ. Manag. 2012, 34, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, S.; Sidanius, J.; Rabinowitz, J.L.; Federico, C. Ethnic Identity, Legitimizing. Ideologies, and Social Status: A Matter of Ideological Asymmetry. Polit. Psychol. 1998, 19, 373–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trigkas, M.; Partalidou, M.; Lazaridou, D. Trust and other historical proxies of social capital: Do they matter in promoting social entrepreneurship in Greek rural areas? J. Soc. Entrep. 2020, 2, 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.L.; Li, W. Economic status and social attitudes of migrant workers in China. China World Econ. 2007, 15, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honohan, P. Cross-country variation in household access to financial services. J. Bank. Financ. 2008, 32, 2493–2500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williams, J.C. The class culture gap. In Facing Social Class: How Societal Rank Influences Interaction; Fiske, S.T., Markus, H.R., Eds.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- Son, J.; Niehm, L.S. Using social media to navigate changing rural markets: The case of small community retail and service businesses. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2021, 33, 619–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidanius, J.; Liu, J.H.; Shaw, J.S.; Pratto, F. Social dominance orientation, hierarchy attenuators and hierarchy enhancers: Social dominance theory and the criminal justice system. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1994, 24, 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berreman, G.D. Caste in India and the United State. Amer. J. Soc. 1960, 66, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Bönteb, W.; Tamvada, J.P. Religion, social class, and entrepreneurial choice. J. Bus. Ventur. 2013, 28, 774–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, P.H.; Aldrich, H.E. Social Capital and Entrepreneurship. Found. Trends Entrep. 2005, 1, 245–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H. Analysis on management of entrepreneurial environment for migrant workers. Asian Agr. Res. 2016, 8, 79–82. [Google Scholar]

- Boubakri, N.; Cosset, J.C.; Saffar, W. Political connections of newly privatized firms. J. Corp. Financ. 2008, 14, 654–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Maarten, B.T.; Oli, R.M.; Tom, E. Toward a Theory of Family Social Capital in Wealthy Transgenerational Enterprise Families. Entrep. Theory. Pract. 2022, 46, 159–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y. Source and functions of Urbanites’ social capital: A network approach. Soc. Sci. China 2004, 3, 136–146. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Structures, Habitus, Power: Basis for a theory of symbolic power. In Culture/Power/History: A Reader in Contemporary Social Theory; Dirks, N.B., Eley, G., Ortner, S.B., Eds.; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1994; pp. 155–199. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, B.; Kish-Gephart, J.J. Encountering social class differences at work: How “class work” perpetuates inequality. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2013, 38, 670–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addae, E.A. The mediating role of social capital in the relationship between socio-economic status and adolescent wellbeing: Evidence from Ghana. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological Conditions of Personal Engagement and Disengagement at Work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, B.J.; Kim, T.H.; Nurunnabi, M.; Jung, S.Y. Does a good firm breed good organizational citizens? The moderating role of perspective taking. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, C.; Liao, J.Q.; Wen, P. Why does formal mentoring matter? The mediating role of psychological safety and the moderating role of power distance orientation in the Chinese context. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Man. 2014, 25, 1112–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusserow, A. When hard and soft clash: Class-based individualism in Manhattan and Queens. In Facing Social Class: How Societal Rank Influences Interaction; Fiske, S.T., Markus, H.R., Eds.; Russell Sage Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 195–215. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Zur, H.; Zeidner, M. Threat to life and risk-taking behaviors: A review of empirical findings and explanatory models. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2009, 13, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, H.E.; Lott, B. Social class and power. In The Social Psychology of Power; Guinote, A., Vescio, T.K., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 408–427. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, E.B.; Menon, T.; Thompson, L. Status differences in the cognitive activation of social networks. Organ. Sci. 2012, 23, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Keltner, D.; Gruenfeld, D.H.; Anderson, C. Power, approach and inhibition. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 110, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shipler, D.K. The Working Poor: Invisible in America, 1st ed.; Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, J.S.; Han, S.; Keltner, D. Feelings and Consumer Decision Making: The Appraisal-Tendency Framework. J. Consum. Psychol. 2007, 17, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miller, G.; Chen, E.; Cole, S.W. Health Psychology: Developing Biologically Plausible Models Linking the Social World and Physical Health. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2009, 60, 501–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Leana, C.R.; Mittal, V.; Stiehl, E. Organizational behavior and the working poor. Organ. Sci. 2012, 23, 888–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, S.L.; Thomas, A.S. Culture and entrepreneurial potential: A nine country study of locus of control and innovativeness. J. Bus. Ventur. 2001, 16, 51–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boente, W.; Filipiak, U. Financial literacy, information flows, and caste affiliation: Empirical evidence from India. J. Bank Financ. 2012, 36, 3399–3414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, J.M.R.; Sakhel, A.; Busch, T. Corporate investments and environmental regulation: The role of regulatory uncertainty, regulation-induced uncertainty, and investment history. Eur. Manag. J. 2017, 35, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, M.W.; Heath, P.S. The growth of the firm in planned economies in transition: Institutions, organizations, and strategic choice. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1996, 21, 492–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peng, M.W. Business strategies in transition economies. Admin. Sci. Quart. 2000, 46, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manolova, T.R.; Eunni, R.V.; Gyoshev, B.S. Institutional environments for entrepreneurship: Evidence from emerging economies in Eastern Europe. Entrep. Theory Prac. 2008, 32, 203–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samllbone, D.; Welterb, F. Entrepreneurship and institutional change in transition economies: The Commonwealth of Independent States, Central and Eastern Europe and China compared. Entrep. Region. Dev. Int. J. 2012, 24, 215–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulen, H.; Ion, M. Policy Uncertainty and Corporate Investment. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2016, 29, 523–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.R.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S.J. Measuring Economic Policy Uncertainty. Q. J. Econ. 2016, 131, 1593–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.X.; Zhang, X.C. Research on the Impact of external Shocks on the Price Fluctuation of Agricultural products in China—Based on the perspective of agricultural industry chain. J. Manag. World 2011, 1, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Li, G. Does policy uncertainty restrain investment of agricultural enterprises. J. Agrotech. Econo. 2021, 8, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Homroy, S. Managerial incentives and strategic choices of firms with different ownership structures. J. Corp. Financ. 2018, 48, 314–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mirza, S.S.; Ahsan, T. Corporates’ strategic responses to economic policy uncertainty in China. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; He, X.G.; Li, Z.Y. Family structure and farmer entrepreneurship: Based on the Data analysis of The Thousand Villages Survey in China. China Ind. Econ. 2017, 12, 170–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.B.; Dibrell, C.; Garrett, R. Examining relationships among family influence, family culture, flexible planning systems, innovativeness and firm performance. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2014, 5, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Bullón, F.; Sanchez-Bueno, M.J.; Nordqvist, M. Growth intentions in family-based new venture teams: The role of the nascent entrepreneur’s R&D behavior. Manag. Decis. 2019, 58, 1190–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A. Organizational learning and entrepreneurship in family firms: Exploring the moderating effect of ownership and cohesion. Small. Bus. Econ. 2012, 38, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, C. Practical Research Methods: A User-Friendly Guide to Mastering Research Techniques and Projects, 1st ed.; How To Books Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.T.; Gu, F.F.; Dong, M.C. Observer Effects of Punishment in a Distribution Network. J. Mark. Res. 2013, 50, 627–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Yan, Z.; Zhuang, G.; Zhou, N.; Dou, W. Interpersonal Influence as an Alternative Channel Communication Behavior in Emerging Markets: The Case of China. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2009, 40, 668–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opper, S.; Nee, V.; Holm, H.J. Risk aversion and guanxi activities: A behavioral analysis of CEOs in China. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 1504–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Janet, M.R. Essentials of Research Methods. A Guide to Social Science Research, 1st ed.; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, O.D. A Socioeconomic Index for All Occupation. In Occupations and Social Status; Reiss, A.J., Ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Singh-Manoux, A.; Adler, N.; Marmot, M. Subjective social status: Its determinants and its association with measures of ill-health in the Whitehall II study. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 56, 1321–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J. Defining the limits of local government power in China: The relevance of international experience. J. Contemp. China. 1995, 4, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.Q.; Jin, Y.L.; Dong, Z.Y. Policy uncertainty, political relevance and firm innovation efficiency. Nankai Manag. Rev. 2016, 19, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Chaine, S.; Goergen, M. The effects of management-board ties on IPO performance. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2013, 21, 153–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.X.; Zheng, X.J.; Cai, W.J. Controlling family’s “from behind the curtain” and corporate financial decisions. Manag. World 2017, 3, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.L.; Fan, G.; Zhu, H.P. Marketization Index of China’s Provinces: NERI Report, 1st ed.; Social Sciences Academic Press: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, G.; Wang, X.; Zhu, H. NERI Index of Marketization of China’s Provinces 2010 Report; Economic Science Press: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nee, V.; Opper, S. Political capital in a market economy. Soc. Forces 2010, 88, 2105–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peng, M.W.; Luo, Y. Managerial ties and firm performance in a transition economy: The nature of a micro-macro link. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 486–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozorgmehr, A.; Thielmann, A.; Weltermann, B. Chronic stress in practice assistants: An analytic approach comparing four machine learning classifiers with a standard logistic regression model. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leković, B.; Uzelac, O.; Fazekaš, T.; Horvat, A.M.; Vrgović, P. Determinants of Social Entrepreneurs in Southeast Europe: GEM Data Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Rodríguez-Cohard, J.C.; Rueda-Cantuche, J.M. Factors affecting entrepreneurial intention levels: A role for education. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2011, 7, 195–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naong, M.N. Promotion of Entrepreneurship Education—A Remedy to Graduates and Youth Unemployment—A Theoretical Perspective. J. Soc. Sci. 2011, 28, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, M. A review of the entrepreneurial behavior of farmers: An Asian-African perspective. Asian J. Agr. Extens. Econ. Soc. 2018, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivy, J. State-controlled economies vs. rent-seeking states: Why small and medium enterprises might support state officials. Entrep. Region. Dev. 2013, 25, 195–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, J.; Woodruff, C. The central role of entrepreneurs in transition economies. J. Econ. Perspect. 2002, 16, 153–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, S.C.; Chi, J.; Liao, J.; Qian, L. How does religious belief promote farmer entrepreneurship in rural China? Econ. Model. 2021, 97, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naminse, E.Y.; Zhuang, J.C.; Zhu, F.Y. The relation between entrepreneurship and rural poverty alleviation in China. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 2593–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Faria, J.R.; Cuestas, J.C.; Mourelle, E. Entrepreneurship and unemployment: A nonlinear bidirectional causality? Econ. Model. 2010, 27, 1282–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Savrul, M. The impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth: GEM data analysis. J. Manag. Mark. Logist. 2017, 4, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rooyen, C. Towards 2050: Trends and scenarios for African agribusiness. Int. Food Agribus. Man. 2014, 17, 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, T.; Palepu, K. Why focused strategies may be wrong for emerging markets. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1997, 75, 41–54. [Google Scholar]

- Puffer, S.M.; McCarthy, D.J.; Boisot, M. Entrepreneurship in Russia and China: The impact of formal institutional voids. Entrep. Theory Prac. 2010, 34, 441–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.Z.; Li, J.T. Exporting and innovating among emerging market firms: The moderating role of institutional development. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2018, 49, 222–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.Y.; Li, J.T. The development of entrepreneurship in China. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2008, 25, 335–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Area | Frequency | Percentage | Cumulative Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Southeast | 4227 | 30.931 | 30.931 |

| 2 | Bohai Rim | 1646 | 12.044 | 42.975 |

| 3 | Central region | 2830 | 20.708 | 63.684 |

| 4 | Northeast | 731 | 5.349 | 69.033 |

| 5 | Southwest | 2425 | 17.745 | 86.777 |

| 6 | Northwest | 1807 | 13.223 | 100 |

| 13,666 | 100 |

| Variable | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Farmer entrepreneurship | 0.282 | 0.450 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 2 | Family social status | 3.197 | 0.770 | 0.234 *** | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 3 | Regional policy uncertainty | 0.379 | 0.234 | 0.010 | −0.009 | 1.000 | |||||||

| 4 | Local family culture | 1.148 | 0.290 | 0.007 | 0.004 | 0.370 *** | 1.000 | ||||||

| 5 | Gender | 0.740 | 0.439 | 0.139 *** | 0.058 *** | 0.055 *** | 0.031 *** | 1.000 | |||||

| 6 | Age | 45.020 | 11.956 | −0.020 ** | 0.006 | −0.011 | −0.037 *** | 0.135 *** | 1.000 | ||||

| 7 | Marital status | 0.895 | 0.307 | 0.117 *** | 0.044 *** | 0.031 *** | 0.001 | 0.037 *** | 0.414 *** | 1.000 | |||

| 8 | Skills | 0.331 | 0.471 | 0.063 *** | 0.061 *** | 0.014 | 0.027 *** | 0.091 *** | −0.009 | 0.039 *** | 1.000 | ||

| 9 | Network | 133.890 | 149.910 | 0.318 *** | 0.218 *** | 0.019 ** | 0.025 *** | 0.127 *** | −0.156 *** | 0.039 *** | 0.073 *** | 1.000 | |

| 10 | Family size | 3.041 | 0.909 | −0.016 * | −0.007 | 0.095 *** | 0.138 *** | 0.007 | −0.054 *** | 0.014 | 0.009 | 0.012 | 1.000 |

| 11 | Cadre proportion | 0.040 | 0.128 | 0.021 ** | 0.072 *** | 0.002 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.153 *** | 0.052 *** | −0.010 | 0.006 | −0.082 *** |

| 12 | Male proportion | 0.481 | 0.212 | 0.008 | −0.007 | −0.018 ** | 0.013 | 0.039 *** | −0.051 *** | −0.028 *** | −0.011 | 0.007 | −0.195 *** |

| 13 | Single-parent family | 0.032 | 0.177 | −0.022 ** | −0.030 *** | 0.004 | 0.020 ** | 0.016 * | 0.028 *** | −0.011 | 0.009 | −0.034 *** | −0.008 |

| 14 | Cultivated land per capita | 2.076 | 5.149 | 0.079 *** | 0.033 *** | 0.074 *** | −0.061 *** | 0.060 *** | 0.016 * | 0.033 *** | 0.008 | 0.048 *** | −0.057 *** |

| 15 | Per capita income of family | 3.750 | 5.928 | 0.268 *** | 0.280 *** | −0.083 *** | −0.136 *** | 0.054 *** | −0.062 *** | −0.032 *** | 0.039 *** | 0.267 *** | −0.133 *** |

| 16 | Entrepreneurship atmosphere | 3.145 | 10.038 | 0.119 *** | 0.058 *** | 0.030 *** | 0.044 *** | 0.035 *** | −0.037 *** | 0.027 *** | 0.072 *** | 0.157 *** | 0.021 ** |

| 17 | Per capita income of village | 0.092 | 0.180 | −0.018 ** | −0.009 | −0.095 *** | −0.160 *** | −0.023 *** | −0.027 *** | −0.024 *** | 0.007 | 0.015 * | −0.044 *** |

| 18 | Number of permanent resident households | 7.624 | 0.932 | 0.005 | −0.028 *** | −0.061 *** | −0.015 * | −0.024 *** | −0.032 *** | −0.018 ** | 0.012 | 0.047 *** | −0.017 ** |

| 19 | Number of companies | 8.698 | 16.997 | 0.009 | 0.012 | −0.098 *** | −0.083 *** | −0.034 *** | −0.032 *** | −0.030 *** | 0.006 | 0.068 *** | −0.057 *** |

| 20 | Number of migrant households | 3.678 | 2.961 | −0.018 ** | 0.005 | −0.156 *** | −0.229 *** | −0.062 *** | −0.059 *** | −0.053 *** | 0.002 | 0.073 *** | −0.065 *** |

| 21 | Number of families involved in entrepreneurial activities | 14.440 | 43.643 | 0.010 | −0.001 | −0.018 ** | 0.038 *** | −0.004 | −0.051 *** | −0.011 | 0.002 | 0.048 *** | −0.001 |

| 22 | Marketization index | 7.468 | 1.870 | 0.001 | 0.018 ** | −0.239 *** | −0.440 *** | −0.039 *** | 0.083 *** | 0.001 | −0.005 | 0.021 ** | −0.101 *** |

| Variable | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | |

| 11 | Cadre proportion | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| 12 | Male proportion | 0.061 *** | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 13 | Single-parent family | 0.022 *** | −0.006 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 14 | Cultivated land per capita | 0.044 *** | 0.045 *** | 0.011 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 15 | Per capita income of family | −0.012 | 0.090 *** | −0.017 ** | 0.055 *** | 1.000 | |||||||

| 16 | Entrepreneurship atmosphere | −0.006 | 0.000 | −0.002 | 0.005 | 0.061 *** | 1.000 | ||||||

| 17 | Per capita income of village | −0.020 ** | −0.006 | −0.006 | 0.000 | 0.099 *** | −0.014 * | 1.000 | |||||

| 18 | Number of permanent resident households | 0.003 | 0.011 | −0.016 * | −0.076 *** | 0.077 *** | 0.030 *** | −0.129 *** | 1.000 | ||||

| 19 | Number of companies | −0.016 * | 0.006 | −0.021 ** | −0.069 *** | 0.154 *** | 0.066 *** | 0.075 *** | 0.303 *** | 1.000 | |||

| 20 | Number of migrant households | −0.042 *** | 0.008 | −0.025 *** | −0.086 *** | 0.174 *** | 0.019 ** | 0.164 *** | 0.441 *** | 0.379 *** | 1.000 | ||

| 21 | Number of families involved in entrepreneurial activities | 0.019 ** | 0.006 | −0.006 | 0.026 *** | 0.023 *** | 0.054 *** | −0.023 *** | 0.106 *** | 0.156 *** | 0.085 *** | 1.000 | |

| 22 | Marketization index | 0.033 *** | 0.016 * | −0.037 *** | −0.109 *** | 0.210 *** | −0.015 * | 0.124 *** | 0.195 *** | 0.270 *** | 0.322 *** | −0.028 *** | 1.000 |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.575 *** | 0.575 *** | 0.575 *** | 0.575 *** | 0.574 *** |

| (0.054) | (0.054) | (0.054) | (0.054) | (0.054) | |

| Age | −0.010 *** | −0.010 *** | −0.010 *** | −0.010 *** | −0.010 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Marital status | 1.213 *** | 1.213 *** | 1.215 *** | 1.212 *** | 1.216 *** |

| (0.095) | (0.095) | (0.095) | (0.095) | (0.095) | |

| Skills | 0.077 * | 0.077 * | 0.076 * | 0.077 * | 0.078 * |

| (0.045) | (0.045) | (0.045) | (0.045) | (0.045) | |

| Network | 0.003 *** | 0.003 *** | 0.003 *** | 0.003 *** | 0.003 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Family size | −0.014 | −0.014 | −0.014 | −0.014 | −0.014 |

| (0.024) | (0.024) | (0.024) | (0.024) | (0.024) | |

| Cadre proportion | 0.176 | 0.176 | 0.171 | 0.177 | 0.176 |

| (0.165) | (0.165) | (0.166) | (0.166) | (0.166) | |

| Male proportion | −0.158 | −0.159 | −0.159 | −0.158 | −0.160 |

| (0.104) | (0.104) | (0.104) | (0.104) | (0.104) | |

| Single-parent family | −0.178 | −0.178 | −0.180 | −0.178 | −0.179 |

| (0.127) | (0.127) | (0.127) | (0.127) | (0.127) | |

| Cultivated land per capita | 0.019 *** | 0.019 *** | 0.019 *** | 0.019 *** | 0.019 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |

| Per capita income of family | 0.079 *** | 0.079 *** | 0.079 *** | 0.079 *** | 0.079 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |

| Entrepreneurship atmosphere | 0.027 *** | 0.027 *** | 0.027 *** | 0.027 *** | 0.027 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| Per capita income of village | −0.345 *** | −0.345 *** | −0.348 *** | −0.346 *** | −0.352 *** |

| (0.130) | (0.130) | (0.130) | (0.130) | (0.130) | |

| Number of permanent resident households | 0.034 | 0.033 | 0.032 | 0.034 | 0.033 |

| (0.027) | (0.027) | (0.027) | (0.027) | (0.027) | |

| Number of companies | −0.003 * | −0.003 * | −0.003 * | −0.003 * | −0.002 * |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Number of migrant households | −0.042 *** | −0.042 *** | −0.042 *** | −0.042 *** | −0.043 *** |

| (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | |

| Number of families involved in entrepreneurial activities | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Marketization index | −0.020 | −0.019 | −0.019 | −0.020 | −0.019 |

| (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.014) | (0.014) | |

| Family social status | 0.437 *** | 0.437 *** | 0.437 *** | 0.437 *** | 0.435 *** |

| (0.030) | (0.030) | (0.030) | (0.030) | (0.030) | |

| Regional policy uncertainty | 0.016 | −0.003 | |||

| (0.087) | (0.089) | ||||

| Family social status×Regional policy uncertainty | 0.228 * | ||||

| (0.121) | |||||

| Local family culture | −0.008 | −0.041 | |||

| (0.084) | (0.085) | ||||

| Family social status×Local family culture | 0.298 *** | ||||

| (0.100) | |||||

| _cons | −4.199 *** | −4.200 *** | −4.198 *** | −4.188 *** | −4.145 *** |

| (0.275) | (0.275) | (0.275) | (0.296) | (0.296) | |

| Chi2 | 2618.909 | 2618.942 | 2622.604 | 2618.919 | 2627.815 |

| R2_p | 0.161 | 0.161 | 0.161 | 0.161 | 0.162 |

| n | 13,666 | 13,666 | 13,666 | 13,666 | 13,666 |

| Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.595 *** | 0.595 *** | 0.593 *** | 0.595 *** | 0.595 *** |

| (0.067) | (0.067) | (0.067) | (0.067) | (0.067) | |

| Age | −0.012 *** | −0.012 *** | −0.012 *** | −0.012 *** | −0.012 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| Marital status | 1.301 *** | 1.301 *** | 1.306 *** | 1.302 *** | 1.306 *** |

| (0.118) | (0.118) | (0.118) | (0.118) | (0.118) | |

| Skills | 0.059 | 0.059 | 0.057 | 0.059 | 0.058 |

| (0.053) | (0.053) | (0.053) | (0.053) | (0.053) | |

| Network | 0.003 *** | 0.003 *** | 0.003 *** | 0.003 *** | 0.003 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Family size | −0.011 | −0.011 | −0.013 | −0.012 | −0.011 |

| (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.029) | (0.030) | |

| Cadre proportion | 0.037 | 0.036 | 0.035 | 0.034 | 0.032 |

| (0.182) | (0.182) | (0.183) | (0.183) | (0.183) | |

| Male proportion | −0.132 | −0.131 | −0.134 | −0.135 | −0.135 |

| (0.125) | (0.125) | (0.125) | (0.126) | (0.126) | |

| Single-parent family | −0.235 | −0.235 | −0.231 | −0.236 | −0.233 |

| (0.151) | (0.151) | (0.151) | (0.151) | (0.151) | |

| Cultivated land per capita | 0.020 *** | 0.020 *** | 0.020 *** | 0.020 *** | 0.020 *** |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |

| Per capita income of family | 0.075 *** | 0.075 *** | 0.075 *** | 0.075 *** | 0.075 *** |

| (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.005) | |

| Entrepreneurship atmosphere | 0.018 *** | 0.018 *** | 0.018 *** | 0.018 *** | 0.018 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |

| Per capita income of village | −0.358 ** | −0.357 ** | −0.357 ** | −0.354 ** | −0.357 ** |

| (0.156) | (0.156) | (0.156) | (0.156) | (0.156) | |

| Number of permanent resident households | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.030 | 0.030 |

| (0.032) | (0.032) | (0.032) | (0.032) | (0.032) | |

| Number of companies | −0.002 | −0.002 | −0.002 | −0.002 | −0.002 |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Number of migrant households | −0.038 *** | −0.038 *** | −0.038 *** | −0.037 *** | −0.037 *** |

| (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | (0.011) | |

| Number of families involved in entrepreneurial activities | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Marketization index | −0.023 | −0.022 | −0.023 | −0.020 | −0.019 |

| (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.016) | (0.016) | |

| Family social status | 0.445 *** | 0.445 *** | 0.445 *** | 0.444 *** | 0.443 *** |

| (0.035) | (0.035) | (0.035) | (0.035) | (0.035) | |

| Regional policy uncertainty | 0.042 | −0.052 | |||

| (0.113) | (0.124) | ||||

| Family social status×Regional policy uncertainty | 0.282 * | ||||

| (0.151) | |||||

| Local family culture | 0.057 | −0.037 | |||

| (0.102) | (0.109) | ||||

| Family social status×Local family culture | 0.285 ** | ||||

| (0.119) | |||||

| _cons | −4.167 *** | −4.189 *** | −4.149 *** | −4.242 *** | −4.129 *** |

| (0.333) | (0.338) | (0.338) | (0.358) | (0.360) | |

| Chi2 | 1765.445 | 1765.584 | 1769.085 | 1765.764 | 1771.512 |

| R2_p | 0.160 | 0.160 | 0.160 | 0.160 | 0.160 |

| n | 8596 | 8596 | 8596 | 8596 | 8596 |

| Model 11 | Model 12 | Model 13 | Model 14 | Model 15 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.296 *** | 0.296 *** | 0.294 *** | 0.293 *** | 0.293 *** |

| (0.056) | (0.057) | (0.057) | (0.060) | (0.060) | |

| Age | −0.006 *** | −0.006 *** | −0.006 *** | −0.006 *** | −0.006 *** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Marital status | 0.601 *** | 0.602 *** | 0.604 *** | 0.595 *** | 0.595 *** |

| (0.116) | (0.117) | (0.118) | (0.125) | (0.125) | |

| Skills | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.016 | 0.016 | 0.017 |

| (0.041) | (0.041) | (0.041) | (0.042) | (0.042) | |

| Network | 0.001 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.001 *** | 0.001 ** | 0.001 ** |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Family size | −0.016 | −0.016 | −0.017 | −0.016 | −0.016 |

| (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.015) | (0.015) | |

| Cadre proportion | −0.105 | −0.104 | −0.107 | −0.115 | −0.115 |

| (0.226) | (0.227) | (0.227) | (0.233) | (0.232) | |

| Male proportion | −0.030 | −0.030 | −0.030 | −0.026 | −0.027 |

| (0.082) | (0.083) | (0.083) | (0.085) | (0.085) | |

| Single-parent family | −0.040 | −0.040 | −0.038 | −0.036 | −0.037 |

| (0.091) | (0.091) | (0.091) | (0.093) | (0.093) | |

| Cultivated land per capita | 0.011 *** | 0.011 *** | 0.011 *** | 0.010 *** | 0.010 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| Per capita income of family | 0.027 | 0.027 | 0.027 | 0.026 | 0.026 |

| (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.021) | (0.021) | |

| Entrepreneurship atmosphere | 0.010 *** | 0.010 *** | 0.010 *** | 0.010 *** | 0.010 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Per capita income of village | −0.111 | −0.111 | −0.113 | −0.108 | −0.110 |

| (0.113) | (0.114) | (0.114) | (0.115) | (0.115) | |

| Number of permanent resident households | 0.036 * | 0.036 * | 0.036 * | 0.038 * | 0.037 * |

| (0.022) | (0.022) | (0.021) | (0.022) | (0.022) | |

| Number of companies | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.001 | −0.001 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Number of migrant households | −0.022 *** | −0.023 *** | −0.023 *** | −0.023 *** | −0.023 *** |

| (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | (0.006) | |

| Number of families involved in entrepreneurial activities | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Marketization index | −0.007 | −0.007 | −0.007 | −0.008 | −0.008 |

| (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | |

| Family social status | 0.691 * | 0.690 * | 0.699 * | 0.714 * | 0.715 * |

| (0.411) | (0.414) | (0.412) | (0.426) | (0.424) | |

| Regional policy uncertainty | −0.015 | −0.029 | |||

| (0.056) | (0.057) | ||||

| Family social status×Regional policy uncertainty | 0.234 *** | ||||

| (0.070) | |||||

| Local family culture | −0.024 | −0.037 | |||

| (0.053) | (0.052) | ||||

| Family social status×Local family culture | 0.130 | ||||

| (0.082) | |||||

| _cons | −3.723 *** | −3.714 *** | −3.731 *** | −3.755 *** | −3.741 *** |

| (1.143) | (1.159) | (1.152) | (1.143) | (1.138) | |

| Chi2 | 2517.967 | 2516.551 | 2545.908 | 2577.966 | 2593.045 |

| n | 13,666 | 13,666 | 13,666 | 13,666 | 13,666 |

| Model 16 | Model 17 | Model 18 | Model 19 | Model 20 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 0.450 *** | 0.450 *** | 0.450 *** | 0.450 *** | 0.450 *** |

| (0.056) | (0.056) | (0.056) | (0.056) | (0.056) | |

| Age | −0.017 *** | −0.017 *** | −0.017 *** | −0.017 *** | −0.017 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.002) | |

| Marital status | 1.165 *** | 1.166 *** | 1.167 *** | 1.165 *** | 1.168 *** |

| (0.095) | (0.095) | (0.095) | (0.095) | (0.095) | |

| Skills | −0.070 | −0.070 | −0.071 | −0.070 | −0.069 |

| (0.048) | (0.048) | (0.048) | (0.048) | (0.048) | |

| Network | 0.002 *** | 0.002 *** | 0.002 *** | 0.002 *** | 0.002 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Family size | −0.054 ** | −0.055 ** | −0.054 ** | −0.054 ** | −0.054 ** |

| (0.025) | (0.025) | (0.025) | (0.025) | (0.025) | |

| Cadre proportion | 0.142 | 0.141 | 0.136 | 0.142 | 0.143 |

| (0.166) | (0.166) | (0.166) | (0.166) | (0.166) | |

| Male proportion | −0.061 | −0.062 | −0.063 | −0.060 | −0.064 |

| (0.105) | (0.105) | (0.105) | (0.105) | (0.105) | |

| Single-parent family | −0.170 | −0.170 | −0.172 | −0.170 | −0.171 |

| (0.127) | (0.127) | (0.127) | (0.127) | (0.127) | |

| Cultivated land per capita | 0.015 *** | 0.015 *** | 0.015 *** | 0.015 *** | 0.015 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |

| Per capita income of family | 0.027 *** | 0.027 *** | 0.027 *** | 0.026 *** | 0.027 *** |

| (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | (0.008) | |

| Entrepreneurship atmosphere | 0.026 *** | 0.026 *** | 0.026 *** | 0.026 *** | 0.026 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| Per capita income of village | −0.340 *** | −0.340 *** | −0.343 *** | −0.341 *** | −0.348 *** |

| (0.130) | (0.130) | (0.130) | (0.130) | (0.130) | |

| Number of permanent resident households | 0.028 | 0.028 | 0.027 | 0.028 | 0.028 |

| (0.027) | (0.027) | (0.027) | (0.027) | (0.027) | |

| Number of companies | −0.003 * | −0.003 * | −0.003 * | −0.003 * | −0.003 * |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Number of migrant households | −0.043 *** | −0.043 *** | −0.043 *** | −0.044 *** | −0.044 *** |

| (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | (0.009) | |

| Number of families involved in entrepreneurial activities | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.000 |

| (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | |

| Marketization index | −0.025 ** | −0.025 ** | −0.024 * | −0.026 * | −0.025 * |

| (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.013) | (0.014) | (0.014) | |

| IMR | −1.849 *** | −1.849 *** | −1.847 *** | −1.850 *** | −1.841 *** |

| (0.223) | (0.223) | (0.223) | (0.223) | (0.224) | |

| Family social status | 0.407 *** | 0.408 *** | 0.407 *** | 0.408 *** | 0.406 *** |

| (0.031) | (0.031) | (0.031) | (0.031) | (0.031) | |

| Regional policy uncertainty | 0.015 | −0.002 | |||

| (0.088) | (0.089) | ||||

| Family social status×Regional policy uncertainty | 0.224 * | ||||

| (0.121) | |||||

| Local family culture | −0.015 | −0.045 | |||

| (0.085) | (0.085) | ||||

| Family social status×Local family culture | 0.303 *** | ||||

| (0.101) | |||||

| _cons | −0.825 * | −0.827 * | −0.828 * | −0.805 | −0.777 |

| (0.490) | (0.490) | (0.490) | (0.503) | (0.503) | |

| Chi2 | 2675.956 | 2675.987 | 2679.518 | 2675.987 | 2685.021 |

| R2_p | 0.165 | 0.165 | 0.165 | 0.165 | 0.165 |

| n | 13,648 | 13,648 | 13,648 | 13,648 | 13,648 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, C.; He, X.; Wang, X.; Nie, J. The Influence of Family Social Status on Farmer Entrepreneurship: Empirical Analysis Based on Thousand Villages Survey in China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8450. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148450

Yang C, He X, Wang X, Nie J. The Influence of Family Social Status on Farmer Entrepreneurship: Empirical Analysis Based on Thousand Villages Survey in China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8450. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148450

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Chan, Xiaogang He, Xiaoyan Wang, and Jinjun Nie. 2022. "The Influence of Family Social Status on Farmer Entrepreneurship: Empirical Analysis Based on Thousand Villages Survey in China" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8450. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148450

APA StyleYang, C., He, X., Wang, X., & Nie, J. (2022). The Influence of Family Social Status on Farmer Entrepreneurship: Empirical Analysis Based on Thousand Villages Survey in China. Sustainability, 14(14), 8450. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148450