The second objective is to identify the predictors of QOL and to find out their correlation, or difference, in the residents of cities and villages. We consider a predictor to be a variable that correlates with QOL at a correlation coefficient level of 0.30 or more. The variables in our paper include happiness, quality of place, and quality of environment. Predictors of QOL are not only important for the development of its epistemology but also as a basis for public policy. The third step consists of the analysis of the findings.

2.1. Cities and Urban Life

Czechia inhabitants live in 608 cities and 5651 villages; the official designation of both types of settlements is “municipality“, in Czech “obec”. According to the Czech Act on Municipalities No. 128/2000 “

a municipality is a basic territorial self-governing community of citizens”. A municipality with a population of at least 3000 residents is a town if the President of the Chamber of Deputies of the Parliament of the Czech Republic so determines, after the Government has expressed its opinion [

28]. In the paper, a municipality with a population of 5000 or more is considered a city.

Since the beginning of human history, cities have been the carriers of creativity, inventiveness, and human development in all its forms—from spiritual, social, economic, and technical to artistic. Unlike in the past, when their distinction from villages was clear, today it is not. One of the most commonly used criteria for determining whether a village is still a village, or already a city, is the number of residents. However, according to Dijkstra et al. [

29], this criterion varies not only between continents (Argentina 2000, Japan 50,000 inhabitants) but also within continents (Denmark 200, Czechia 5000—India 5000, China 100,000 inhabitants). The European Social Survey does not solve the village-city problem by quantification but by self-definition—a village is a settlement that has been identified as a village or a city by a survey participant [

30]. Theoretical issues regarding cities and villages, defining cities, development and processes influencing contemporary post-industrial cities, is explored by Petrovič, Murgaš [

5].

In terms of development, cities are broadly divided into pre-industrial, industrial, and post-industrial. Today’s cities became post-industrial when industrial society changed to post-industrial society after World War II, first in the USA and then in other Western countries. The criterion for change was a change in employment—employment in services exceeded that in industry. From a process perspective, Van den Berg et al. [

9] divided urban development into four stages: urbanization, suburbanization, deurbanization, and reurbanization.

According to the UN [

6], 55% of the world’s population lives in cities, the least with 32% in “least developed countries”, the most with 79% in “more developed countries”. The only European country with a city population of less than 50% is Moldova, with 43%. Cities now play a key role in global development, accounting on the one hand for more than 80% of world GDP, but on the other hand for 70% of greenhouse gas emissions [

18].

The urban population is growing globally, but urbanization is highly differentiated. In developed countries with complex processes of suburbanization, reurbanization, deurbanization, urban sprawl, and shrinking cities, the population is growing slowly and even declining in some size categories. The attention of researchers, urban planners and local politicians is focused on improving the QOL in them. It can be concluded that the growth in quantity, i.e., the number of city residents, has stopped and turned into quality improvement, i.e., the transformation of cities into pleasant places to live.

The rapid growth of urbanization in the world began in the second half of the 20th century. In 1960, a total of 1.019 billion people lived in cities, representing 33.6% of humanity. The number of people living in cities reached 2 billion in 1986, representing 41.5% of humanity. Three billion people lived in cities in 1993, and 4 billion in 2016. In 2020, 4.2 billion people lived in cities. The largest cities in developing countries accounted for a crucial share of urbanization growth [

31]. Population growth in 2022, compared to 2021, was highest in Kinshasa (Democratic Republic of Congo), up 4.39%; Lagos (Nigeria), up 3.54%; and Dhaka (Bangladesh), up 3.39% [

6]. Encouragingly, the number of people living in slums is declining. Of the world’s urban population, 39.6% lived in slums in 2000, 35.5% in 2005, 33.2% in 2010 and 29.2% in 2018 [

31]. Despite these positive developments, it is true that the growth of urbanization in developing countries has not yet stopped; in other words, the increasing quantity does not allow to deal with the improvement of the QOL of all the inhabitants of these countries. It is positive that, despite the above, research on QOL is also ongoing in Least Developed Countries [

16,

17,

18], enriching the epistemology of QOL with a non-Western perspective.

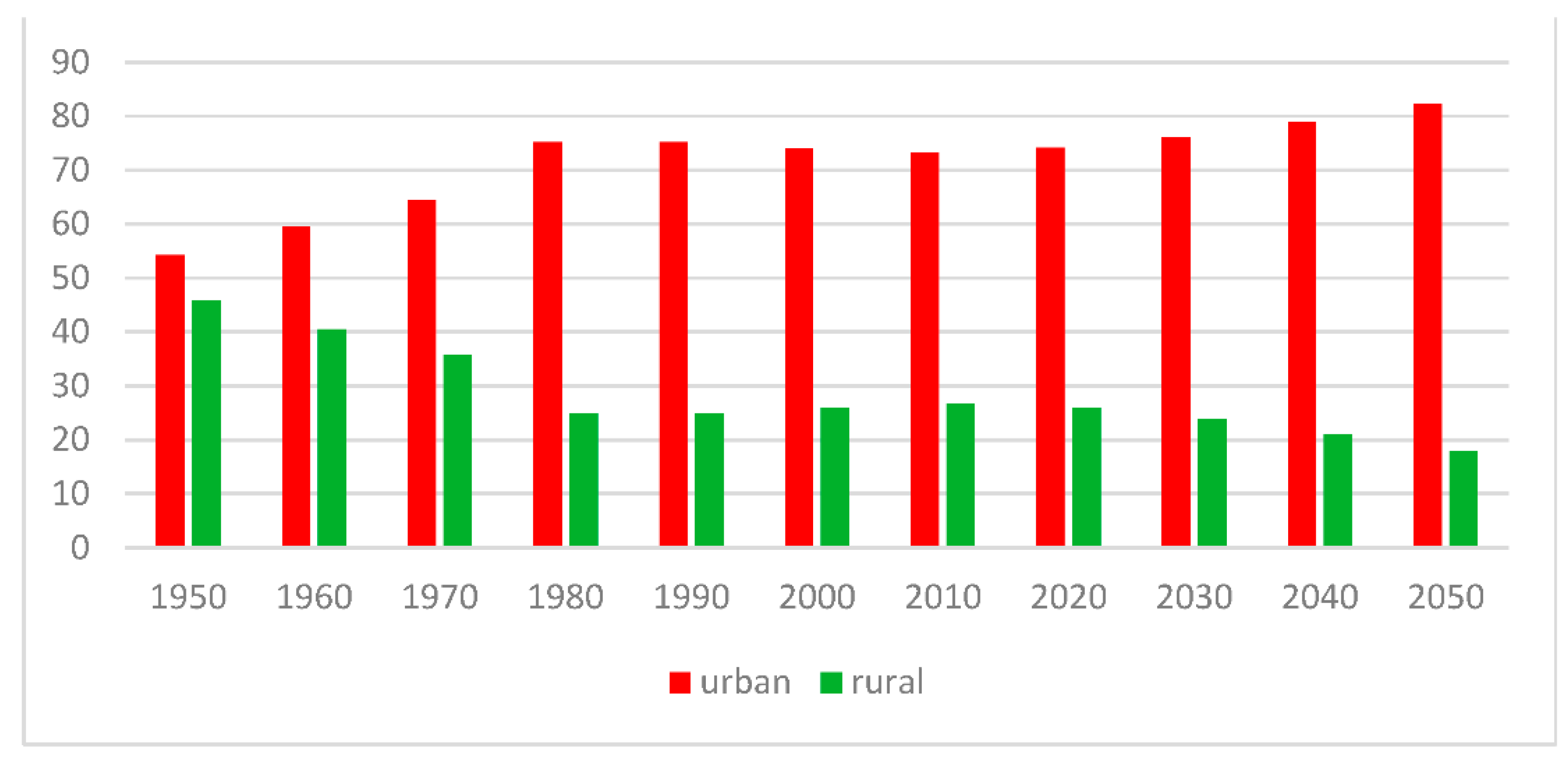

The number of people living in cities accounts for 75% in Europe and 69% in Czechia [

32]. The expected future development of urbanization is highly differentiated; Okulicz-Kozaryn [

7] projects an urbanization rate of more than 80% in Europe in 2050, while UN [

6] projects an urbanization rate of 82% in Czechia for 2050 (

Figure 1). Alderton et al. [

8] project the fastest urbanization growth in low-to-middle-income countries.

In examining the quality of urban life, it is essential to start by defining the city, but this is not easy. In the past, cities were surrounded by walls and the position of “intra muros” and “extra muros” (Latin for “inside the walls” and “behind the walls”) clearly distinguished the city from the countryside. Contemporary cities are characterized by large numbers of people commuting daily to cities, or students commuting to schools for long periods of time. At the same time, the residents of villages in the territory of big cities live the same way of life as urban residents. The agricultural function of villages, which was dominant in the past, is now marginal.

Petrovič, Murgaš [

5] define city as follows: “The present city is a complex system of social, economic, and environmental ties of people living usually in large numbers (The term “usually in large numbers” means that the criterion of 100,000 s of residents does not always apply, e.g. in the case of Denmark.) and permanently in one place”. The definition refers to “social” life in the city. Without the criterion of a large population, it would also be the definition of a village. In terms of the epistemology of quality of life, it expresses a measure of satisfaction with urban life. However, the complexity of urban life requires it to be complemented by the existing technical and environmental infrastructure that enables social life. Infrastructure, together with population, is what distinguishes a city from a village. In terms of the epistemology of quality of life, the infrastructure of the city constitutes the quality of place.

In Czechia in 1950 (Czechia was part of Czechoslovakia between 1918 and 1992.) the majority of the population already lived in cities, the figure of 54% was the highest among the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Between 1950 and 2018, urbanization grew steadily, with significant growth until 1980, before slowing down. According to UN [

17], 74% of the Czech population lived in urban areas in 2018, the same as the European average. The largest city is Prague, which in 2021 had 1.3 million residents, with the second most populous city being Brno, with 380,000 residents. Overall, there are six cities (including Prague and Brno) with more than 100,000 residents according to CZSOs [

33].

Since 2010, the rate of urbanization in Czechia has been stagnating, as has the rate of urbanization in the six largest cities over 100,000 residents. The complexity of urbanization development in Czechia can be illustrated using the example of the city of Ostrava, the third most populous city in the country, with 285,000 residents. This important industrial center had 184,000 residents in 1950. By 1970, the population had grown by more than 50% to 278,000. Ostrava had the highest population in 1991 at 327,000. Economic reforms in the centers of mining and heavy industry brought mass unemployment, which caused the population to decline; between 1990 and 2005 there was a decline of 8% [

34], the most of any regional city. Both major demographic components, natural and out-migration, contributed to the decline. In 2012, the population dropped below 300,000, and the decline continues to the present day [

33].

In all regions, the urbanization rate is higher than 50%: the lowest is in the Central Bohemian Region in the territory of Prague, with 52%; the highest with 82% in the Karlovy Vary Region [

32]. According to Kašparová, Půček [

35], the size structure of Czech cities is similar to that of the surrounding countries of Central and Eastern Europe. It is characterized by a capital city with a population above 1 million and few cities above 100,000, referred to as “big cities”. The rate of “big city urbanization” is 21% in the Czech Republic: the lowest in Europe is Portugal (9%); the highest in Cyprus (52%).

2.2. Villages, Rural Life

Svobodová et al. [

10] estimate the number of all rural settlements in Czechia, i.e., hamlets, remote villages, hill settlements and villages, to be 40,000. This means that a distinctive feature of the settlement structure in this country is its fragmentation.

The number of papers focused on the quality of rural life is increasing. This also brings papers oriented on specific groups of the population, e.g., the elderly [

11]. In 2018, an issue of the journal

European Countryside, focusing on the quality of urban life, was published [

12]. Some papers are focused on comparing urban and rural QOL [

19].

We believe that, despite the legitimate attention given to the issue of cities and the QOL in them, it makes sense to also focus on rural settlements and the QOL in them. Our belief is based on the following two facts:

- (i)

A significant number of residents still live in the villages;

- (ii)

Villages are closely linked to the countryside, which makes up a substantial part of the land area of each country.

For centuries, rural settlements have fulfilled their main function of providing enough food for their residents, and urban residents. The Industrial Revolution has also had an impact on agriculture, resulting in an increase in food production. The number of people employed in agriculture declined steadily after the World War II, and in recent decades the number of people in villages keeping animals, and growing agricultural products for their own consumption, has also fallen significantly. People living in rural settlements in Central and Eastern Europe commute to cities for work, as in the past, but the way of life in cities has changed considerably. Villagers live an urban lifestyle, a statement that is even more true the more equipped a village is, when it is located in a developed region, and when it is close to a regional center. The characteristics of the type of villages described also include a higher number of university-educated residents.

As with cities, rural settlements in least developed countries differ significantly from rural settlements in more developed countries. In Western countries, villages differ significantly even within a single country. There is a big difference between a village with a growing population near a regional city, to which city residents are moving, and a depopulating village on the periphery, with no employment opportunities, and where both shops and pubs have ceased to exist. If such a village is lucky enough to be in a tourist attraction area, the empty houses are bought by well-off city residents for recreational purposes. Countryside residents regard poor access to well-paid jobs and a rich social life as the main drawbacks of living in the countryside. Urban residents consider good access to nature as the main positive of living in the countryside [

12].

The big issue of the urban-rural dichotomy is its typology. The OECD [

14] has changed its approach in view of the large differences in the population criterion necessary for classifying a municipality as urban. It proposed a population density criterion of 150 inhabitants per km

2. It divided the regions into three categories:

- (i)

Predominantly Urban, if the share of population living in rural municipalities is below 15%;

- (ii)

Intermediate, if the share of population living in municipalities is between 15% and 50%;

- (iii)

Predominantly Rural, if the share of population living in municipalities is higher than 50%.

Perlin [

36] applied the OECD [

37] methodology and used a density criterion of 150 inhabitants per km

2 and divided (

Figure 2) Czechia into rural and urban regions. It is clear that the rural regions dominate in absolute numbers.

Figure 2 highlights the need for increased attention to rural regions and the QOL in them. The OECD [

14] categorization has been adopted by Eurostat [

38].

The countryside has been undergoing serious structural problems in recent decades, requiring the attention of local residents, political authorities from local to national and European level, and last but not least, from researchers. In response to this observation, the Czech Minister of Agriculture has identified improving the quality of rural life as a key objective of agricultural reform [

29]. Efforts are being made to link “bottom-up” activities in the form of support for the emergence of local initiatives and training of local leaders. In 1993, the non-profit Association for Rural Renewal was established, its mission being: to contribute to the renewal and deepening of social and spiritual life in the countryside; to strengthen rural prosperity; and to motivate citizens to volunteer for the benefit of the community. The most well-known activity of the Association is the competition “Village of the Year”. The “top-down” activity included the establishment of non-profit “Local Action Group” (in Czech—Místní akční skupina) as a community of both public and private sector. The aim of the Local Action Group is to “participate in rural renewal and development in order to improve the QOL in the countryside” [

39].