Industry 4.0 in Financial Services: Mobile Money Taxes, Revenue Mobilisation, Financial Inclusion, and the Realisation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Africa

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Industry 4.0 in the Financial Services Sector in Africa

2.2. Mobile Money Usage, Financial Inclusion, and the Achievement of SDGs in Africa

2.3. Mobile Money Taxes (MMTs) in Africa

2.4. Motives for Introducing Mobile Money Taxes in Africa

2.5. Criticism of Mobile Money Taxes in Africa

2.5.1. Mobile Money Taxes Policy Formulation

2.5.2. Mobile Money Taxes and the Principles of a Good Tax System

2.5.3. Mobile Money Taxes and the Multiplicity of Taxes in the Telecoms Sector

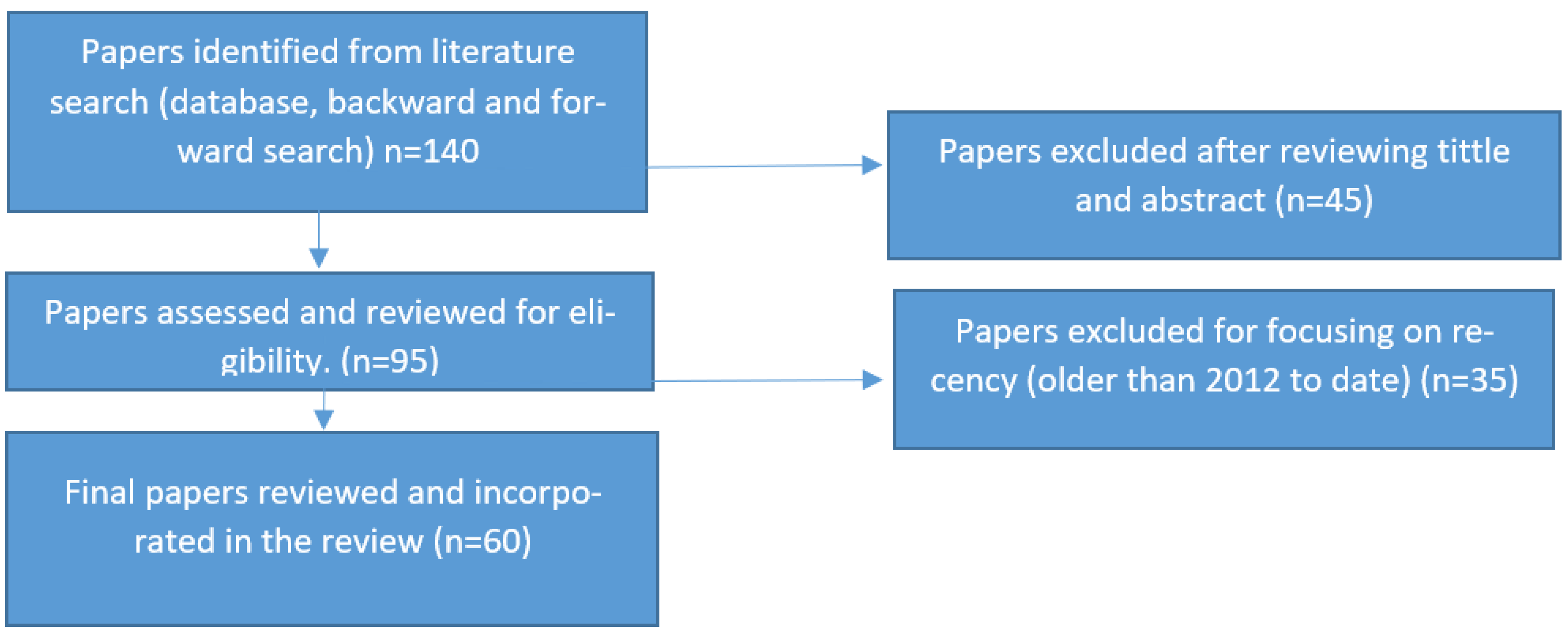

3. Materials and Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Mobile Money and Revenue Mobilisation

4.2. Mobile Money, Mobile Money Tax, and Financial Inclusion

4.3. Mobile Money Taxes, Revenue Generation, Economic Growth, and Financial Inclusion in African Countries

4.4. Financial Inclusion and the Attainment of Selected Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

4.5. Discussion

4.5.1. Possible Effect on Consumers

4.5.2. Possible Impact on Businesses, SMEs, and Mobile Service Providers

4.5.3. Possible Effect on the Government

4.5.4. Implications of Mobile Money Taxes and Customer Privacy and Confidentiality

5. Conclusions, Recommendations, and Areas for Further Research

5.1. Recommendations

- Improvement in the design of mobile money taxes in line with the canons of taxation. Currently, as discerned from the literature review, mobile money taxes in most African countries are the converse of a good tax system guided by the canons of taxation or principles of an ideal tax system, such as equity, convenience, fairness, neutrality, certainty, and efficiency. Therefore, perhaps in trying to align mobile money taxes with the revenue mobilisation goals, financial inclusion, social inclusion, and the attainment of SDGs, African governments must rethink the design of mobile money taxes in line with the principles of taxation. For example, as highlighted earlier in the literature, Zimbabwe is the only country that has added similar taxes to the mobile money taxes to the formal banking transactions such as swipes and transfers. To uphold the principle of equity, both horizontal and vertical, bank transactions must be subjected to taxes similar to those in other African countries. The discriminatory structure of these taxes, which do not cover financial institutions, points to the regressive nature of mobile money taxes. Therefore, extending these taxes to the banking sector would help address the fairness and equity concerns, thus boosting tax morale. Governments also must consider that for some incomes, taxation of mobile money transactions is taxation of already taxed income that was subjected to PAYE for the formally employed (double taxation implications).

- In terms of convenience, the mobile money tax systems must be made to uphold this principle. Governments must find a way that does burden service providers (deemed agents such as banks and mobile networks) with responsibilities of tax computation, collection, remittances, and general accountability, in addition to their own other tax-related obligations of filing for tax returns on corporate tax, VAT, and PAYE.

- Simplification of mobile money tax legislation to reduce complexity, instability, and uncertainty. Tax legislation is not stable as it is constantly changing, increasing compliance costs, and negatively affecting investor expectations.

- Taxation of DFSs should be more favourable, including the taxation of mobile money by adequately assessing the implications for poverty alleviation, sustainable economic growth, and development as well as the realisation of SDGs such as poverty alleviation, reduction in inequalities, and creating decent work as well as building strong institutions as these SDGs are linked to financial inclusion and economic growth.

- More research on DFS taxes, mobile money taxes, and the impact of these taxes on the wider development goals. There is a dearth of research, literature, and policy contributions on mobile money taxes. Future researchers could perhaps continue to research how to tax mobile money without stifling the mobile money services’ growth and unfavourably affecting the undeserved and underrepresented groups and the generally marginalised.

5.2. Limitations and Areas for Further Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GSMA. The Causes and Consequences of Mobile Money Taxation. An Examinination of Mobile Money Taxation in Sub Saharan Africa. 2020. Available online: https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/resources/the-causes-and-consequences-of-mobile-money-taxation-an-examination-of-mobile-money-transaction-taxes-in-sub-saharan-africa/ (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Ndung’u, N.S. Taxing Mobile Phone Transactions in Africa: Lessons from Kenya. 2019. Available online: https://www.africaportal.org/publications/taxing-mobile-phone-transactions-africa-lessons-kenya/ (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Karombo, T. “It’s a Lazy Tax”. Why African Governments’ Obesssion with Mobile Money Could Back Fire. 2022. Available online: https://restofworld.org/2022/how-mobile-money-became-the-new-cash-cow-for-african-governments-but-at-a-cost/ (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Ahmed, S.; Chinembiri, T.; Govan-Vassen, N. COVID-19 Exposes the Contradictions of Social Media Taxes in Africa. 2021. Available online: https://www.africaportal.org/documents/21197/COVID-19-social_media_taxes_in_Africa.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Ahmad, A.H.; Green, C.; Jiang, F. Mobile money, financial inclusion and development: A review with reference to African experience. J. Econ. Surv. 2020, 34, 753–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magwape. Digital Sales Tax in Africa and the COVID-19 Pandemic. 2021. Available online: https://kluwerlawonline.com/journalarticle/Intertax/50.4/TAXI2022039 (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Silue, T. E-Money, Financial Inclusion and Mobile Money Tax in Sub-Saharan African Mobile Networks. 2021. Available online: https://hal.uca.fr/hal-03281898/document (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- Pushkareva, N. Taxing Times for Development: Tax and Digital Financial Services in Sub-Saharan Africa. Financ. Dev. 2021, 1, 33–64. [Google Scholar]

- Shipalana, P. Digitising Financial Services: A Tool for Financial Inclusion in South Africa? 2019. Available online: https://www.africaportal.org/documents/19566/Occasional-Paper-301-shipalana.pdf (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- Simatele, M. E-payment instruments and welfare: The case of Zimbabwe. TD J. Transdiscipl. Res. South. Afr. 2021, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlanga, D. Industry 4.0 in finance: The impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on digital financial inclusion. Int. J. Financ. Stud. 2020, 8, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlanga, D.; Dunga, S.H.; Moloi, T. Financial inclusion and poverty alleviation among smallholder farmers in Zimbabwe. Eurasian J. Econ. Financ. 2020, 8, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agur, I.; Peria, S.M.; Rochon, C. Digital financial services and the pandemic: Opportunities and risks for emerging and developing economies. Int. Monet. Fund Spec. Ser. COVID-19 Trans. 2020, 1, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Ouma, S.A.; Odongo, T.M.; Were, M. Mobile financial services and financial inclusion: Is it a boon for savings mobilization? Rev. Dev. Financ. 2017, 7, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cull, R.; Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Lyman, T. Financial Inclusion and Stability: What Does Research Show? 2012. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/9443/713050BRI0CGAP0f0FinancialInclusion.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- Tan, K.W. Africa’s Mobile Money Taxes Risk Driving the Poor out of the Digital Economy. 2022. Available online: https://klse.i3investor.com/web/blog/detail/kianweiaritcles/2022-05-26-story-h1623426654-Africa_s_mobile_money_taxes_risk_driving_poor_out_of_digital_economy (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Triki, T.; Faye, I. Financial Inclusion in Africa. African Development Bank. 2013. Available online: https://www.rfilc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Financial_Inclusion_in_Africa.pdf (accessed on 22 March 2022).

- Evans, O. Connecting the poor: The internet, mobile phones and financial inclusion in Africa. Digit. Policy Regul. Gov. 2018, 20, 568–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutsonziwa, K.; Maposa, O.K. Mobile money-A catalyst for financial inclusion in developing economies: A case study of Zimbabwe using FinScope survey data. Int. J. Financ. Manag. 2016, 6, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Koomson, I.; Martey, E.; Etwire, P.M. Mobile money and entrepreneurship in East Africa: The mediating roles of digital savings and access to digital credit. Inf. Technol. People, 2022; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Asongu, S.A.; Biekpe, N.; Cassimon, D. Understanding the greater diffusion of mobile money innovations in Africa. Telecommun. Policy 2020, 44, 102000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baganzi, R.; Lau, A.K.W. Examining trust and risk in mobile money acceptance in uganda. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rotondi, V.; Billari, F.C. Mobile money and school participation: Evidence from Africa. Popul. Res. Policy Rev. 2022, 41, 343–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukari, C.; Koomson, I. Adoption of mobile money for healthcare utilization and spending in rural Ghana. In Moving from the Millennium to the Sustainable Development Goals; Palgrave Macmillan: Singapore, 2020; pp. 37–60. [Google Scholar]

- Sekantsi, L.P. Digital financial services uptake in Africa and its role in financial inclusion of women. J. Digit. Bank. 2019, 4, 161–174. [Google Scholar]

- Munoz, L.; Mascagni, G.; Prichard, W.; Santoro, F. Should Governments Tax Digital Financial Services? A Research Agenda to Understand Sector-Specific Taxes on DFS. 2022. Available online: https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/17171/ICTD_WP136.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Kakungulu-Mayambala, R.; Rukundo, S. Implications of Uganda’s new social media tax. East Afr. J. Peace Hum. Rights 2018, 24, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthiora, B. Enabling Mobile Money Policies in Kenya. Fostering the Digital Revolution. Mobile Money for the Ubanked. GSMA. 2015. Available online: https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/resources/enabling-mobile-money-policies-in-kenya-fostering-a-digital-financial-revolution/ (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- Sebele-Mpofu, F.Y. Governance quality and tax morale and compliance in Zimbabwe’s informal sector. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1794662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebele-Mpofu, F.Y. The Informal Sector, the “implicit” Social Contract, the Willingness to Pay Taxes and Tax Compliance in Zimbabwe. Account. Econ. Law A Conviv. 2021, 2021, 20200084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebele-Mpofu, F.Y.; Moyo, N. An Evil to be Extinguished or a Resource to be harnessed-Informal Sector in Developing Countries: A Case of Zimbabwe. J. Econ. Behav. Stud. 2021, 13, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpofu, F.Y.S. Taxing the informal sector through presumptive taxes in Zimbabwe: An avenue for a broadened tax base, stifling of the informal sector activities or both. J. Account. Tax. 2021, 13, 153–177. [Google Scholar]

- Mpofu, F.Y.S. Informal Sector Taxation and Enforcement in African Countries: How plausible and achievable are the motives behind? A Critical Literature Review. Open Econ. 2021, 4, 72–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, M. Harnessing the Power of Mobile Money to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. GSMA. 2019. Available online: https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/resources/harnessing-the-power-of-mobile-money-to-achieve-the-sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- Scharwatt, C. Mobile money competing with the Informal Channels to Accelerate Digitalisation of Remittances. 2018. Available online: https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/resources/competing-with-informal-channels-to-accelerate-the-digitisation-of-remittances/ (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Clifford, K. The Causes and Consequences of Mobile Money Taxation An Examination of Mobile Money Transaction Taxes in Sub-Saharan Africa. 2020. Available online: https://www.ictd.ac/event/mobile-money-taxation-africa-causes-consequences/ (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Mpofu, F.Y. Review Articles: A Critical Review of the Pitfalls and Guidelines to effectively conducting and reporting reviews. Technium Soc. Sci. J. 2021, 18, 550. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, H. Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 104, 333–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, B.V.; Banister, D. How to write a literature review paper? Transp. Rev. 2016, 36, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sebele-Mpofu, F.Y. Saturation controversy in qualitative research: Complexities and underlying assumptions. A literature review. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2020, 6, 1838706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlan, M.; Cronin, P. Doing a Literature Review in Nursing, Health and Social Care; Sage: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bandara, W.; Miskon, S.; Fielt, E. A systematic, tool-supported method for conducting literature reviews in information systems. In Proceedings of the 19th European Conference on Information Systems, ECIS 2011, Helsinki, Finland, 9–11 June 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jalali, S.; Wohlin, C. Systematic literature studies: Database searches vs. backward snowballing. In Proceedings of the 2012 ACM-IEEE International Symposium on Empirical Software Engineering and Measurement, Lund, Sweden, 20–21 September 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; Watson, M. Guidance on conducting a systematic literature review. J. Plan. Educ. Res. 2019, 39, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, Y.; Ellis, T.J. A systems approach to conduct an effective literature review in support of information systems research. Inf. Sci. 2006, 9, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sebele-Mpofu, F.; Mashiri, E.; Schwartz, S.C. An exposition of transfer pricing motives, strategies and their implementation in tax avoidance by MNEs in developing countries. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1944007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebele-Mpofu, F.Y.; Mashiri, E.; Korera, P. Transfer Pricing Audit Challenges and Dispute Resolution Effectiveness in Developing Countries with Specific Focus on Zimbabwe. Account. Econ. Law A Conviv. 2021, 2021, 000010151520210026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebele, F.; Gomera, D.; Sibanda, B. Tax incentives: A panacea or problem to enhancing economic growth in developing countries. J. Account. Financ. Audit. Stud. JAFAS 2022, 8, 90–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandaogo, A.A.; Sawadogo, F.; Lastunen, J. Does the Adoption of Peer-to-Government Mobile Payments Improve Tax Revenue Mobilization in Developing Countries? No. wp-2022-18; World Institute for Development Economic Research (UNU-WIDER): Helsinki, Finland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, M. Harnessing Digital Financial Solutions. In Innovative Humanitarian Financing; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 213–230. [Google Scholar]

- Mwesigwa, A. Mobile money—Why MTN remains ahead of rivals. Retrieved 2013, 11, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chinoda, T.; Kwenda, F. Financial Inclusion Condition of African Countries; Acta Universitatis Danubius, Œconomica: Galați, Romania, 2019; Volume 15. [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan, G.; Marktanner, M. The growth potential from financial inclusion. ICA Inst. Kennesaw State Univ. 2012, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sarma, M.; Road, L.; Paris, J. Financial Inclusion and Development: A Cross Country Analysis. 2008. Available online: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/summary?doi=10.1.1.533.5991 (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Mhlanga, D. Financial Inclusion and Poverty Reduction: Evidence from Small Scale Agricultural Sector in Manicaland Province of Zimbabwe. Ph.D. Thesis, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Della Peruta, M. Adoption of mobile money and financial inclusion: A macroeconomic approach through cluster analysis. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2018, 27, 154–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GSMA. State of the Industry Report on Mobile Money 2021. 2021. Available online: https://www.adfi.org/publications/state-industry-report-mobile-money-2021-gsma (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Levin, J. After the Pandemic—An Opening for Tax Reforms: Post-COVID Taxation Challenges across Africa: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet. 2022. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1634130&dswid=8380 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Bunn, D.; Asen, E.; Enache, C. Digital Taxation around the World; Tax Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://files.taxfoundation.org/20200527192056/Digital-Taxation-Around-the-World.pdf (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- Santoro, F.; Munoz, L.; Prichard, W.; Mascagni, G. Digital Financial Services and Digital IDs: What Potential do They Have for Better Taxation in Africa? 2022. Available online: https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/17113/ICTD_WP137.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Onuoha, R.; Gillwald, A. Digital Taxation: Can It Contribute to More just Resource Mobilisation in Post-Pandemic Reconstruction? 2022. Available online: https://www.africaportal.org/documents/22459/Digital-Taxation-contribute-to-more-just-resource-mobilisation-in-post-pandemi_HbbLoxs.pdf (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- Dzogbenuku, R.K.; Amoako, G.K.; Kumi, D.K.; Bonsu, G.A. Digital payments and financial wellbeing of the rural poor: The moderating role of age and gender. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2021, 4, 113–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mswahili, A. Factors for Acceptance and Use of Mobile Money Interoperability Services. J. Inform. 2714-1993 2022, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Akinyemi, B.E.; Mushunje, A. Determinants of mobile money technology adoption in rural areas of Africa. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2020, 6, 1815963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’dri, L.M.; Kakinaka, M. Financial inclusion, mobile money, and individual welfare: The case of Burkina Faso. Telecommun. Policy 2020, 44, 101926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawczynski, O. Exploring the usage and impact of “transformational” mobile financial services: The case of M-PESA in Kenya. J. East. Afr. Stud. 2009, 3, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okello Candiya Bongomin, G.; Ntayi, J.M.; Munene, J.C.; Malinga, C.A. Mobile money and financial inclusion in sub-Saharan Africa: The moderating role of social networks. J. Afr. Bus. 2018, 19, 361–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Klapper, L.; Singer, D.; Ansar, S.; Hess, J. Opportunities for Expanding Financial Inclusion through Digital Technology. 2018. Available online: https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/abs/10.1596/978-1-4648-1259-0_ch6 (accessed on 26 April 2022).

- Demirgüç-Kunt, A.; Singer, D. Financial Inclusion and Inclusive Growth: A Review of Recent Empirical Evidence. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper (No. 8040). 2017. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2958542 (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- Burns, S. M-Pesa and the ‘market-led’ approach to financial inclusion. Econ. Aff. 2018, 38, 406–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATAF. Taxing the Digital Economy: COVID-19 Heightens the Need to Expand Resource Mobilisation Base. 2020. Available online: https://www.ataftax.org/taxing-the-digital-economy-covid-19-heightens-need-to-expand-resource-mobilisation-base (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Burns, S. Mobile Money and Financial Development: The Case of M-PESA in Kenya. 2015. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2688585 (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- Mhlanga, D. The Role of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: What Lessons Are We Learning on 4IR and the Sustainable Development Goals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voica, M.C. Financial Inclusion as a Tool for Sustainable Development. 2017. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/a/ine/journl/v44y2017i53p121-129.html (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Chinoda, T.; Akande, J.O. financial inclusion, mobile phone diffusion, and economic growth; evidence from Africa. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2019, 9, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Inoue, T. Financial inclusion and poverty reduction in India. J. Financ. Econ. Policy 2018, 11, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pazarbasioglu, C.; Mora, A.G.; Uttamchandani, M.; Natarajan, H.; Feyen, E.; Saal, M. Digital Financial Services; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; 54p. [Google Scholar]

- Shapshack, T. Mobile Money in Africa Reaches $500billion during the Pandemic. 2021. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/tobyshapshak/2021/05/19/mobile-money-in-africa-reaches-nearly-500bn-during-pandemic/ (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- The Africa Report. Mobile Money Key to Africa’s Growth But Bad Tax Policies Ruin it. 2020. Available online: https://www.theafricareport.com/46993/mobile-money-key-to-africas-growth-but-bad-tax-policies-ruin-it/ (accessed on 16 March 2022).

- Van Hove, L.; Dubus, A. M-PESA and financial inclusion in Kenya: Of paying comes saving? Sustainability 2019, 11, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Muthiora, B.; Raithatha, R. Rethinking Mobile Money Taxation. 2017. Available online: https://www.gsma.com/mobilefordevelopment/programme/mobile-money/rethinking-mobile-mone-taxation (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- Shinyekwa, I. How Will Recent Taxes on Mobile Money Affect East Africans. 2018. Available online: https://eprcug.org/blog/how-will-recent-taxes-on-mobile-money-affect-east-africans/ (accessed on 2 April 2022).

- De Koker, L.; Jentzsch, N. Financial inclusion and financial integrity: Aligned incentives? World Dev. 2013, 44, 267–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Koker, L. The 2012 revised FATF recommendations: Assessing and mitigating mobile money integrity risks within the new standards framework. Wash. J. Law Technol. Arts 2013, 8, 165. [Google Scholar]

- de Koker, L.; Goldbarsht, D. Financial technologies and financial crime: Key developments and areas for future research. In Financial Technology and the Law; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 303–320. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A.; Goodman, S.; Traynor, P. Privacy and security concerns associated with mobile money applications in Africa. Wash. JL Tech. Arts 2012, 8, 245. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, A. Mobile money platform surveillance. Surveill. Soc. 2019, 17, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Studies | Focus | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Evan [18] | Mobile money usage and financial inclusion in 44 African countries | Significant positive relationship between mobile money usage, internet access, and financial inclusion |

| Mutsonziwa and Maposa [19] | Mobile money as a driver for financial inclusion in Zimbabwe | Mobile expands financial inclusion, increases productivity, and helps poverty alleviation efforts |

| Ahmad, Green, and Jiang [5] | Mobile money and financial inclusion in Africa | Mobile money contributes to financial inclusion |

| Koomson, Martey, and Etwire [20] | Mobile money and the growth of entrepreneurship | Mobile money influences the growth of entrepreneurship for women, rural dwellers, and the youth. Incomes from entrepreneurship can be used to deliver the achievement of SDG 8, decent work and full productivity and employment generation, SDG 1, poverty reduction, SDG 2 (reduction in hunger and food insecurity), and for purchasing clean energy (SDG 7). |

| Asongu, Biekpe, and Cassimon [21] | Mobile money and inclusive development in Africa | African countries have a larger informal sector, and mobile money is key to poverty reduction and financial inclusion (thus addressing SDGs 1 and 10) |

| Baganzi and Lau, [22]) | Trust and risk in mobile money adoption in Uganda | Mobile money can help in the achievement of SDGs in Uganda to reduce injustice and inequality, poverty eradication, and mitigation of climate change by 2030. Resources saved by, remitted to, and transferred to the previously excluded segments of the population can enable them to fulfil some of the SDGs, thus contributing to national attainment. |

| Rotondi and Billari [23] | How mobile money affects school participation | Mobile money usage allows deposits, transfers, receipts, and withdrawals at reduced transaction costs and from remote areas. This increases chances of children going to school, and parents can pay in an affordable manner, thus achieving SDG 10, reducing inequality, and SDG 1, reducing poverty. |

| Bukari and Koomson [24] | Mobile money for healthcare utilisation in Uganda | Mobile money usage enhances the rural population’s utilisation of healthcare, as they are more able to spend money on healthcare in an affordable and reliable way and can also easily and quickly receive money from relatives in urban areas. |

| Country | Tax | Tax Rate | Effective Date/Proposal Date | Mobile Money Accounts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cameroon | Mobile Money Tax | 0.2% | February 2022 | 19.5 million |

| Ghana | Mobile Money Tax | 1.75% | February 2022 | 12 million |

| Tanzania | Mobile Money Tax | 0.1% | July 2021 | 33 million |

| Zimbabwe | Intermediate Monetary Transfers Tax/Mobile Money | 2% | October 2018 | 9.4 million |

| Uganda | Mobile Money Tax | 0.5% | July 2018 | 27 million |

| Cote d’Ivoire | Mobile Money Tax | 7.2% | January 2019 |

| Country | Description of Mobile Money Tax Policy Formulation |

|---|---|

| Uganda | Generally, the tax policy construction process often involves comprehensive research and incident analysis. Close collaboration and cooperation are required between various stakeholders, such as private and public sectors, Ministry of Finance, and the Ugandan Revenue Authority. Mobile money tax policy was formulated based on a directive from the office of the President. This points to deficiencies in the consultative engagement process, in tax incidence analysis, and the assessment of the likely impacts on users or their responsive behaviour. |

| DRC | Tax policy formulation is generally disorganised with three bodies responsible for its construction. Tax administration is equally fragmented with multiple players. Consultative processes are not prioritised in tax policy design. Taxes are generally imposed. Similar circumstances surround the implementation of mobile money taxes in the country. |

| Cote d’Ivoire | While the 0.5% tax on mobile money was introduced in 2018, it was later repealed and criticised for its lack of consultative engagement; the one introduced in 2019 tried to address public criticism by being expenditure-specific. What remains unknown is whether the taxes are used for the expenditures that their rollout linked them to. In 2019, the country re-introduced a mobile money tax at 7.2%. This was split as follows: 2% for rural digital development, 0.2% for financing cultural expenditure, 0.25% for addressing fraud challenges in the industry, and 4.75% for general taxes. |

| Malawi | Tax policy changes or amendments are generally proposed through budgets by the Ministry of Finance, after having completed drafts from consultative engagements with other stakeholders such the Malawi Revenue Authority, the public, parliamentary committees, civic organisations, professional bodies, and academics. After all the views have been considered, consolidated, reviewed, and evaluated and tax incidences of the proposed tax assessed, then tax policy is formulated. Mobile money taxes were formulated, inspired by other countries, and benchmarked in accordance with the tax policy of other countries without considering internal views from different stakeholders that were generally pertinent to tax policy formulation. |

| Zimbabwe | The introduction of the 2% intermediate monetary transfer tax was met with an outcry from the public, telecoms companies, and the Zimbabwe Chamber of Commerce as well industry in general. The issue of the lack of consultation was key on the criticism list as well as the effects on financial inclusion together with affordability concerns. |

| Principle | Articulation in Relation to Mobile Money Taxes |

|---|---|

| Equity | Entails that taxpayers that are similarly situated or have the same incomes in similar conditions must be taxed in the same way (horizontal equity). Vertical equity, on the other hand, considers the ability to pay, meaning those who earn more income must pay more tax and those that earn less pay less. In relation to mobile taxes, the equity or fairness principle is violated as the tax in most countries does extend to the banking sector. It also does not consider the varying circumstances of taxpayers, especially the fact that mobile money platforms are largely used by the underrepresented or underserved segments of the population. Violation of equity lowers tax morale as well as trust in the government and tax morale [29,30]. |

| Certainty | Taxpayers must be certain of their tax liability and how to honour their tax liability. Tax policy must have some consistency and stability, even though it must be dynamic and evolve as the business environment changes. Mobile money tax policy construction in African countries has been fragmented and unstable to a great extent, characterised by proposals, introduction of the taxes, withdrawals of the tax policy, outright repealing, re-implementations, and constant amendments. To say the least, mobile money tax policy has been unstable. This affects policy acceptance and compliance as well as the stability of the business and investment climate. |

| Convenience and economy | Tax policy must be simple to comprehend, not heavily burdensome, and convenient to pay. Though the mobile money tax rates may appear small, when considering the nature of the population served by the mobile money platforms, the taxes are a significant component of incomes, and their impact may be pervasive. Viewed from the angle of service providers, they are burdensome as these providers are already saddled with multiple taxes on telecom companies, as shown in Table 4. The multiplicity of taxes makes mobile money taxes heavy. The service providers are also burdened by the administrative responsibility to collect, aggregate, and remit the taxes to revenue authorities. |

| Efficiency | Considers economic and administrative factors. There is a need for tax policy to strike an equilibrium between the revenue generation and economic development as well as other functions of tax policy. Mobile money taxes are criticised for not paying attention to the possible negative externalities, such as reduced usage, capital flight, and market distortions as well as effects on economic growth and financial inclusion or the attainment of SDGs. Administrative efficiency entails lowering of administrative and compliance costs. |

| Country | Corporate Tax | VAT | Tax/Charge on Cell Phone Airtime | Tax on Mobile Money Operators’ Revenue | Tax on Mobile Money Transactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cote d’Ivoire | 30% | 18% | 3% | 7.2% | |

| DRC | 35% | 16% | 10% | 3% | |

| Kenya | 30% | 16% | 10% | - | 12% |

| Malawi | 30% | 16.5% | 10% | - | 1% |

| Rwanda | 30% | 18% | 10% | - | - |

| Uganda | 30% | 18% | 12% | 10% | 0.5% |

| Zimbabwe | 24.72% | 15% | 10% | - | 2% |

| Tanzania | 30% | 18% | 17% | 10% |

| Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) | Focal Points |

|---|---|

| SDG 1 | Poverty eradication. Countries to work towards eliminating poverty and its manifestations among citizens. |

| SDG 2 | Eradication of hunger. Countries to ensure and enhance sustainable agricultural activities to achieve food security. |

| SDG 3 | Ensure good health and the well-being of citizens. This entails making health facilities also affordable and accessible for all citizens. |

| SDG 4 | Delivering quality education for all. It is important that nations make sure that education is equitable, inclusive, and of good quality for all and offer further learning possibilities. |

| SDG 5 | Addressing gender equality and empowerment of all girls and women. |

| SDG 6 | Provide clean water and sanitation for all. Countries to ensure they have water and sanitation is available to all and on a sustainable basis. |

| SDG 7 | Countries must ensure citizens have access to cheaper, reliable, sustainable, and modernised energy sources. |

| SDG 8 | Decent work and economic growth. Ensure long-term economic growth that is both sustainable and inclusive. Citizens must also have decent work opportunities as well productive employment. |

| SDG 9 | Industrialisation, innovation, and infrastructural development. Countries must promote the building of strong infrastructure, promote sustainable and inclusive industrialisation, and promote innovation. |

| SDG 10 | Reduction in inequalities. Inequalities to be minimised within countries and among them. |

| SDG 11 | Building cities and human settlements that are resilient, inclusive, safe, and sustainable. |

| SDG 12 | Encourage production and consumption that is both responsible and sustainable over time. |

| SDG 13 | Address climate challenges by taking quick steps to deal with climate change and its accompanying impact. |

| SDG 14 | Conserve and protect the lives under water by conservation and sustainable use of seas, oceans, and marine resources to facilitate sustainable development. |

| SDG 15 | Protecting life on the land. Nations must strive to ensure protection, restoration, and promotion of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainable forest management, mitigation of desertification, and reduction in land degradation and combating of biodiversity loss. |

| SDG 16 | To promote peace and justice as well as the building of strong institutions: this could be achieved by countries promoting peaceful and inclusive communities that would foster sustainable development and allow access to justice for everyone. Countries must ensure institutions are inclusive and accountable at all levels. |

| SDG 17 | For the sustainable goals to be achieved, partnerships are key. Nations must enhance the implementation and rejuvenate the global engagements or partnerships to promote sustainable development. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mpofu, F.Y. Industry 4.0 in Financial Services: Mobile Money Taxes, Revenue Mobilisation, Financial Inclusion, and the Realisation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Africa. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8667. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148667

Mpofu FY. Industry 4.0 in Financial Services: Mobile Money Taxes, Revenue Mobilisation, Financial Inclusion, and the Realisation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Africa. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8667. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148667

Chicago/Turabian StyleMpofu, Favourate Y. 2022. "Industry 4.0 in Financial Services: Mobile Money Taxes, Revenue Mobilisation, Financial Inclusion, and the Realisation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Africa" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8667. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148667

APA StyleMpofu, F. Y. (2022). Industry 4.0 in Financial Services: Mobile Money Taxes, Revenue Mobilisation, Financial Inclusion, and the Realisation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Africa. Sustainability, 14(14), 8667. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148667