Impact of Managers’ Emotional Competencies on Organizational Performance

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. The Concept of Emotional Intelligence

- The emotional self-awareness cluster, which implies recognizing one’s own or other people’s strengths and weaknesses through understanding what someone feels. People who have developed competencies from this cluster, such as emotional self-awareness, accurate self-assessment, and self-confidence, create advantages, such as assessing their own or others’ capabilities and limitations, learning based on their own or others’ mistakes, and striving for improvement. These competencies single out employees as “star performers”. Authors Vani, Sankaran and Kumar [30] stated that: “managers with this quality are receptive, work constructively on critical criticism and are focused on learning” (p. 470).

- The emotional self-management cluster is a person’s ability to control anxiety, anger, and emotional impulsivity on one hand, while, on the other hand, it means encouraging the creative and innovative potential of the individual along with developing their strong ambition. This cluster consists of the following competencies: self-control, trustworthiness, conscientiousness, adaptability, achievement drive, and initiative. Possessing these competencies allows leaders to be recognized by employees as someone who makes rational decisions and can be trusted [1] (p. 66).

- The social awareness cluster is a person’s ability to recognize nonverbal cues, such as voice tone, facial expressions, and gestures, that reveal hidden emotions, concerns, and needs. It includes the following competencies: empathy, service orientation, and organizational awareness. By possessing the mentioned competencies, the leader has feedback on how employees react to his business moves and decisions, which can help him in correcting his own behavior to produce a positive impact on employees [1] (p. 67). Individuals with competencies within this cluster can be characterized as effective team players, respecting the principle of trust [30].

- The relationship management cluster is a type of social skill that implies the ability to adapt to others and establish adequate relationships and influence. Therefore, it stands out as a significant competence for visionary leaders in high positions who should be ideal for employees and thus influence the joint implementation of the vision. It consists of the following competencies: developing others, influence, communication, conflict management, leadership, change catalyst, building bonds, and teamwork and collaboration.

2.2. Emotional Intelligence and Organizational Performance

3. Methodology

3.1. The Sample

3.2. The Questionnaire

- Scales related to demographics (gender, age, level of education) and organizational characteristics (sector—public or private, activity, and job of the employee).

- Scales to measure emotional intelligence of top managers, the 360-degree Emotional and Social Competency Inventory—ESCI 360—developed by the consulting company Hay Group in collaboration with Goleman and Boyatzis [61]. This instrument is among the most represented in empirical research. It consists of 68 questions related to 12 competencies grouped into four clusters: emotional self-awareness, self-management (striving for success, adaptability, emotional self-control, optimism), social awareness, and relationship management. For the purpose of this research, the first two clusters describing emotional competencies were analyzed. The questionnaire is based on a five-point Likert scale.

- Scales to measure the respective organizations’ performance for a particular period. Organizational performance was measured by applying subjective criteria that imply the perception of the respondents, in this case the managers, for the last three years. Managers were required to rate their company’s financial, employee, and operational performance using a five-point Likert scale (1. Worse than all competitors, 2. Worse than most competitors, 3. Average performance, 4. Better than most competitors, 5. Better than all competitors).

3.3. Data Processing

4. Results

4.1. Testing the Questionnaire and the Measurement Model

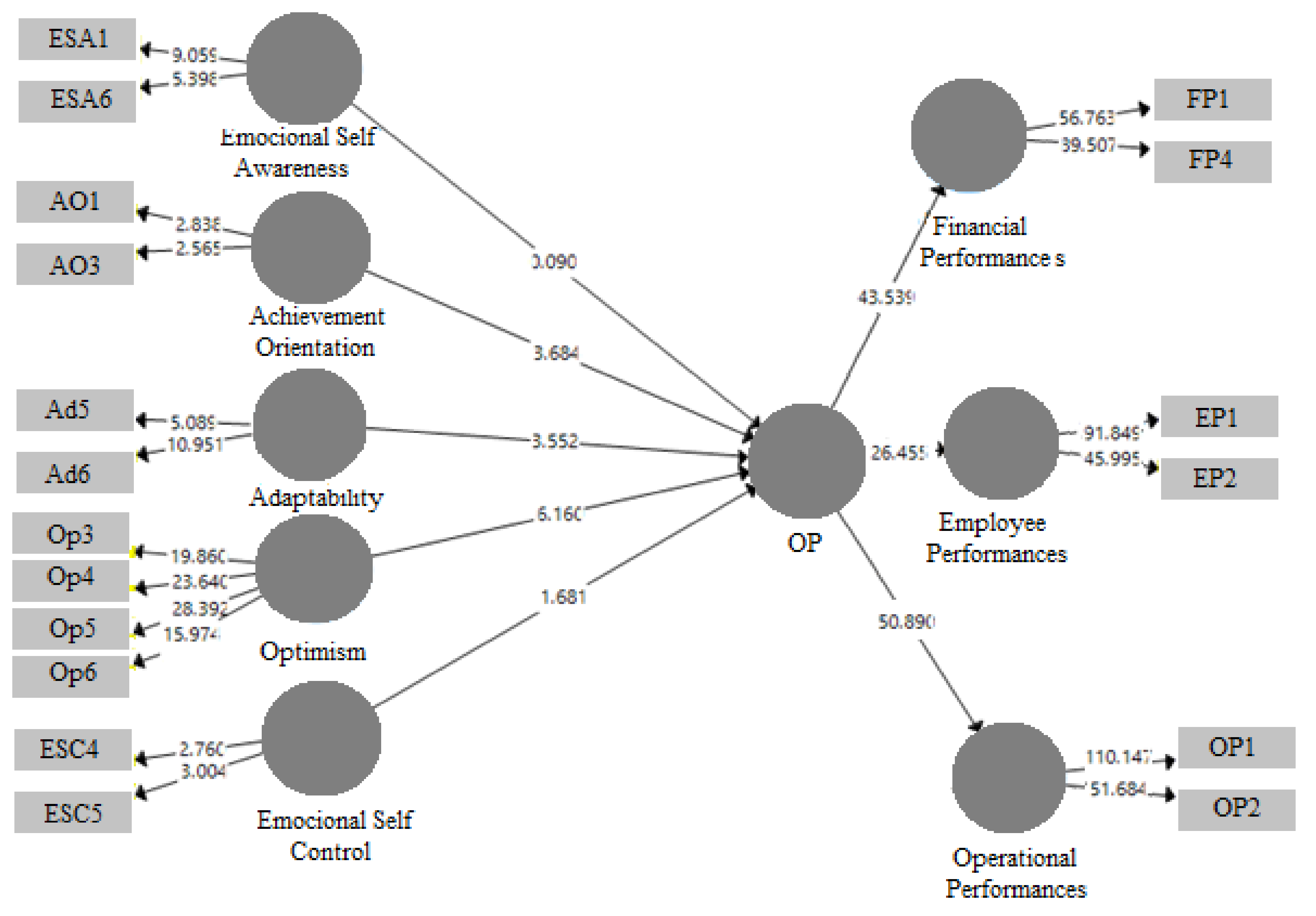

4.2. Testing the Hypothesis and Structural Model

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Implications

6.2. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pinos, V.; Twigg, N.W.; Parayitam, S.; Olson, B.J. Leadership in the 21st century: The effect of emotional intelligence. Electron. Bus. 2013, 12, 61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Boyatzis, R.E. Using tipping points of emotional intelligence and cognitive competencies to predict financial performance of leaders. Psicothema 2006, 18, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brown, C. The effects of Emotional Intelligence (EI) and leadership style on sales performance. Econ. Insights Trends Chall. 2014, 66, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, P.J.; Troth, A. Emotional intelligence and leader member exchange: The relationship with employee turnover intentions and job satisfaction. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2011, 32, 260–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, M. A study of the relationship between emotional intelligence and performance in UK call centers. J. Manag. Psychol. 2004, 19, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supramaniam, S.; Singaravelloo, K. Impact of emotional intelligence on organisational performance: An analysis in the Malaysian Public Administration. Admin. Sci. 2021, 11, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivellasa, P.; Gerogiannisb, V.; Svarnab, S. Exploring Workplace Implications of Emotional Intelligence (WLEIS) in Hospitals: Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intentions. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2011, 73, 701–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gondal, U.H.; Husain, T. A comparative study of intelligence quotient and emotional intelligence: Effect on employees’ performance. Asian J. Bus. Manag. 2013, 5, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharwaney, G. Emotional intelligence. In Educating People to be Emotionally Intelligent; Bar-On, R., Maree, K., Elias, M., Eds.; Heinemann: Sandton, South Africa, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Diggins, C. Emotional intelligence: The key to effective performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. Int. Dig. 2004, 12, 33–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ayranci, E. Effects of top Turkish managers’ emotional and spiritual intelligences on their organizations’ financial performance. Bus. Intell. J. 2011, 4, 9–36. [Google Scholar]

- Oonye, U.; Ogbeta, M.; Ndudi, F.; Bereprebofa, D.; Maduemezia, I. Academic resilience, emotional intelligence, and academic performance among undergraduate students. Knowl. Perform. Manag. 2022, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragoni, L.; Tesluk, P.E.; Russell, J.E.; Oh, I.-S. Understanding managerial development: Integrating developmental assignments, learning orientation, and access to developmental opportunities in predicting managerial competencies. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porath, C.L.; Bateman, T.S. Self-regulation: From goal orientation to job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2006, 91, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenson, A.R.; Van der Stede, W.A.; Cohen, S.G. Measuring the relationship between managerial competencies and performance. J. Manag. 2006, 32, 360–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, M.M. Navigating COVID-19 with emotional intelligence. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 66, 810–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daryanani, R. How to achieve organisational resilience through emotional intelligence—Lessons from Airbus’ group project “+ Emotional energy @ work”. Acad. Lett. 2021, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huy, Q.N. Emotional capability, emotional intelligence, and radical change. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 325–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rexhepi, G.; Berisha, B. The effects of emotional intelligence in employees performance. Int. J. Bus. Glob. 2017, 18, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, T.; Singh, S. Relationship of emotional intelligence with cultural intelligence and change readiness of Indian managers in the service sector. J. Organ. Change Manag. 2021, 34, 1245–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ugoani, J. Emotional intelligence and successful change management in the Nigerian banking industry. Indep. J. Manag. Prod. 2017, 8, 335–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goleman, D. What makes a leader? Harv. Bus. Rev. 1998, 76, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, D. Working with Emotional Intelligence; Bantam Books: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Payne, W.L. A Study of Emotion: Developing Emotional Intelligence; Self-Integration; Relating to Fear, Pain and Desire (Theory, Structure of Reality, Problem-Solving, Contraction/Expansion, Tuning in/Coming Out/Letting Go). Ph.D. Thesis, Union Institute and University Ohio, Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J.D. Emotional Intelligence. Imagin. Cogn. Personal. 1990, 9, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P. Influence of the leaders emotionally intelligent behaviours on their employees job satisfaction. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2013, 12, 799–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bar-On, R. Emotional and social intelligence: Insights from the emotional quotient inventory. In The Handbook of Emotional Intelligence; Bar-On, R., Parker, J., Eds.; Jossey Bass Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rahim, S.H.; Malik, M.I. Emotional intelligence & organizational performance: (A case study of banking sector in Pakistan). Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 5, 191–197. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, D. Emotional intelligence: Issues in paradigm building. Emot. Intell. Workplace 2001, 13, 26. [Google Scholar]

- Vani, M.; Sankaran, H.; Kumar, S.P. Analysis on the Influence of Emotional Intelligence on the Performance of Managers and Organisational Effectiveness in the it Industry. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 2019, 8, 470–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyatzis, R. The Competent Manager: A Model for Effective Performance; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Barrick, M.R.; Mount, M.K. The big five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Pers. Psychol. 1991, 44, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totterdell, P.; Kellett, S.; Teuchmann, K.; Briner, R.R. Evidence of mood linkage in work groups. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 1504–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyatzis, R. The financial impact of competencies in leadership and management of consulting firms. In The Emotionally Intelligent Workplace: How to Select for, Measure, and Improve Emotional Intelligence in Individuals, Groups, and Organizations; Bennis, W., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Q. Leadership Levels and Issues: Lean Briefing Newsletter of Lean Manufacturing Strategy. 2005. Available online: www.strategosinc.com/leadership (accessed on 8 March 2020).

- Martinez, M.N. The smarts that count. HR Mag. 1997, 42, 72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-On, R. BarOn Emotional Quotient Inventory Technical Manual; MHS Publications: Toronto, ON, Canada, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Neale, S.; Spencer-Arnell, L.; Wilson, L. Emotional Intelligence Coaching, Improving Performance for Leaders, Coaches and the Individuals; Kogan Page Limited: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, D. Emotional Intelligence at Work: A Professional Guide, 2nd ed.; Response Books: New Delhi, India, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, R.; Caplan, J. How Bell labs creates star performers. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1993, 71, 128–139. [Google Scholar]

- Supramaniam, S.; Singaravelloo, K. Impact of Emotional Intelligence and Organisational Culture on the Performance of Malaysian Administrative and Diplomatic Officers. Int. Online J. Educ. Leadersh. 2019, 3, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bipath, M. The Dynamic Effects of Leader Emotional Intelligence and Organisational Culture on Organisational Performance. Ph.D. Thesis, Graduate School of Business Leadership University of South Africa, Midrand, South Africa, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ishak, N.M.; Mustapha, R.; Mahmud, Z.; Ariffin, S.R. Emotional intelligence of Malaysian teachers: Implications on workplace productivity. Int. J. Vocat. Educ. Train. 2006, 14, 8–24. [Google Scholar]

- Priti, S.M.; Das, A.K.M. Relevance of emotional intelligence for effective job performance: An empirical study. Vikalpa 2010, 35, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kabagabe, J.B.; Kriek, D. Employee Perceptions of Organisational Emotional Intelligence and Psychological Capital Amongst Public Servants in Uganda. J. Organ. Psychol. 2021, 21, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strumpfer, D.J.W.; Mlonzi, E.N. Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale and job attitudes: Three studies. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2001, 31, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Došenović, D.; Zolak Poljašević, B. The impact of human resource management activities on job satisfaction. Anali 2021, 57, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dramićanin, S.; Perić, G.; Pavlović, N. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment of employees in tourism: Serbian Travel Agency Case. Strateg. Manag. 2021, 26, 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sy, T.; Tram, S.; O’Hara, L.A. Relation of employee and manager emotional intelligence to job satisfaction and performance. J. Vocat. Behav. 2006, 68, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunavathy, J.; Ayswarya, R. Emotional Intelligence and Job Satisfaction as Correlation of Job Performance—A Study Among Women Employed on Indian Software Industry. Paradigm 2011, 15, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baksh Baloch, Q.; Saleem, M.; Zaman, G.; Fida, A. The Impact of Emotional Intelligence on Employees’ Performance. J. Manag. Sci. 2014, 8, 208–227. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Y. The influence of emotional intelligence on job burnout and job performance: Mediating effect of psychological capital. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, F.N.; Chai, L.T.; Aun, L.K.; Migin, M.W. Emotional Intelligence and Turnover Intention. Int. J. Acad. Res. 2014, 6, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, R.S.; Hassan, A. Impact of emotional intelligence on employees turnover rate in FMCG organizations. Pak. J. Commer. Soc. Sci. 2013, 7, 394–404. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup, Inc. State of the AmericanWorkplace. 2017. Available online: https://www.gallup.com/workplace/238085/state-american-workplace-report-2017.aspx (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- O’Boyle, E.H., Jr.; Humphrey, R.H.; Pollack, J.M.; Hawver, T.H.; Story, P.A. The relation between emotional intelligence and job performance: A meta-analysis. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 32, 788–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathi, N. Impact of Emotional Intelligence and Emotional Labor on Organizational Outcomes in Service Organizations: A Conceptual Model. S. Asian J. Manag. 2014, 21, 54–71. [Google Scholar]

- Groth, M.; Hennig-Thurau, T.; Walsh, G. Customer reactions to emotional labor: The roles of employee acting strategies and customer detection accuracy. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 958–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kidwell, B.; Hardesty, D.M.; Murtha, B.R.; Sheng, S. Emotional intelligence in marketing exchanges. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Ok, C.M. Understanding Hotel Employees’ Service Sabotage: Emotional Labor Perspective Based on Conservation of Resources Theory. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HAY Group. Emotional and Social Competency Inventory (ESCI). A User Guide for Accredited Practitioners. Prepared by L&T Direct and the McClelland Center for Research and Innovation. 2011. Available online: https://pdfslide.net/documents/emotional-and-social-competency-inventory-esci-emotional-and-social-competency.html?page=1 (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Fuentes-Fuentes, M.M.; Albacete-Sáez, C.A.; Lloréns-Montes, F.J. The impact of environmental characteristics on TQM principles and organizational performance. Omega 2004, 32, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haricharan, S.J. Is the leadership performance of public service executive managers related to their emotional intelligence? SA J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 20, a1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, J.M.; Klein, K.; Wetzels, M. Hierarchical Latent Variable Models in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for Using Reflective-Formative Type Models. Long Range Plan. 2012, 45, 359–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling: Rigorous Applications, Better Results and Higher Acceptance. Long Range Plan. 2013, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.W. The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. Mod. Methods Bus. Res. 1998, 295, 295–336. [Google Scholar]

- Berber, N.; Slavic, A.; Strugar Jelača, M.; Bjekić, R. The effects of market economy type on the training practice differences in the Central Eastern European region. Empl. Relat. 2020, 42, 971–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Characteristics | N | Percentage of Sample | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| 1. | Male | 53 | 66.3 |

| 2. | Female | 27 | 33.7 |

| Age | |||

| 1. | Less than 25 | 1 | 1.3 |

| 2. | 25–34 | 12 | 15.0 |

| 3. | 35–44 | 19 | 23.8 |

| 4. | 45–55 | 31 | 38.8 |

| 5. | More than 55 | 17 | 21.3 |

| Manager level | |||

| 1. | Top-level | 27 | 33.8 |

| 2. | Middle-level | 32 | 40.0 |

| 3. | Low-level | 21 | 26.2 |

| Company profile | |||

| 1. | Private | 58 | 72.5 |

| 2. | Public | 22 | 27.5 |

| Company size | |||

| 1. | Middle | 39 | 48.8 |

| 2. | Large | 41 | 51.2 |

| Attributes | Loadings | CR | AVE | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Self Awareness (ESA) | 0.783 | 0.644 | ||

| ESA1 Able to describe how own feelings affect own actions. | 0.851 | 1.903 | ||

| ESA6 Acknowledges own strengths and weaknesses. | 0.751 | 1.903 | ||

| Achievement Orientation (AO) | 0.721 | 0.564 | ||

| AO1 Initiates actions to improve own performance. | 0.763 | 1.017 | ||

| AO3 Does not strive to improve own performance. | 0.739 | 1.017 | ||

| Adaptability (Ad) | 0.786 | 0.659 | ||

| Ad5 Adapts to shifting priorities and rapid change. | 0.735 | 1.104 | ||

| Ad6 Adapts overall strategy, goals, or projects to cope with unexpected events. | 0.871 | 1.104 | ||

| Optimism (Op) | 0.863 | 0.612 | ||

| Op3 Views the future with hope. | 0.783 | 1.424 | ||

| Op4 Sees possibilities more than problems. | 0.794 | 1.836 | ||

| Op5 Sees opportunities more than threats. | 0.819 | 1.858 | ||

| Op6 Sees the positive side of a difficult situation. | 0.731 | 1.572 | ||

| Emotional Self Control (ESC) | 0.848 | 0.739 | ||

| ESC4 Remains composed, even in trying moments. | 0.763 | 1.355 | ||

| ESC5 Controls impulses appropriately in situations. | 0.946 | 1.355 | ||

| Financial performance (FP) | 0.908 | 0.831 | ||

| FP1 Growth in profits. | 0.905 | 2.116 | ||

| FP4 Organizational performance is measured by return on equity (financial profitability or ROE). | 0.918 | 2.146 | ||

| Employee performance (EP) | 0.885 | 0.795 | ||

| EP1 Level of employee productivity. | 0.914 | 1.876 | ||

| EP2 Level of employee satisfaction. | 0.868 | 1.745 | ||

| Operational (OP) performance | 0.931 | 0.870 | ||

| OP1 Sales growth. | 0.939 | 2.219 | ||

| OP2 Market share growth. | 0.926 | 2.537 |

| ESA | AO | Ad | Op | ESC | FP | EP | OP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESA1 | 0.851 | 0.086 | 0.567 | 0.285 | 0.424 | 0.186 | 0.115 | 0.104 |

| ESA6 | 0.751 | 0.127 | 0.207 | 0.437 | 0.379 | 0.116 | 0.126 | 0.084 |

| AO1 | 0.035 | 0.763 | 0.329 | 0.139 | 0.241 | −0.014 | −0.117 | −0.146 |

| AO3 | 0.162 | 0.739 | 0.123 | 0.126 | 0.013 | −0.075 | −0.067 | −0.122 |

| Ad5 | 0.519 | 0.180 | 0.735 | 0.271 | 0.377 | 0.123 | 0.086 | 0.153 |

| Ad6 | 0.333 | 0.296 | 0.871 | 0.315 | 0.407 | 0.254 | 0.114 | 0.139 |

| Op3 | 0.287 | 0.187 | 0.229 | 0.783 | 0.198 | 0.268 | 0.380 | 0.231 |

| Op4 | 0.291 | 0.057 | 0.178 | 0.794 | 0.227 | 0.068 | 0.318 | 0.130 |

| Op5 | 0.446 | 0.088 | 0.269 | 0.819 | 0.209 | 0.131 | 0.292 | 0.264 |

| Op6 | 0.347 | 0.195 | 0.479 | 0.731 | 0.196 | 0.086 | 0.291 | 0.219 |

| ESC4 | 0.259 | 0.227 | 0.347 | 0.261 | 0.763 | 0.024 | −0.034 | 0.074 |

| ESC5 | 0.536 | 0.115 | 0.470 | 0.218 | 0.946 | 0.013 | −0.015 | 0.133 |

| FP1 | 0.131 | −0.006 | 0.738 | 0.111 | 0.038 | 0.905 | 0.364 | 0.527 |

| FP4 | 0.217 | −0.097 | 0.792 | 0.243 | −0.002 | 0.918 | 0.441 | 0.563 |

| EP1 | 0.151 | −0.055 | 0.109 | 0.407 | −0.019 | 0.444 | 0.914 | 0.477 |

| EP2 | 0.111 | −0.178 | 0.116 | 0.305 | −0.025 | 0.336 | 0.868 | 0.305 |

| OP1 | 0.188 | −0.124 | 0.216 | 0.274 | 0.191 | 0.662 | 0.393 | 0.939 |

| OP2 | 0.025 | −0.215 | 0.111 | 0.244 | 0.041 | 0.445 | 0.444 | 0.926 |

| ESA | AO | Ad | Op | ESC | FP | EP | OP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESA | 0.802 | |||||||

| AO | 0.129 | 0.751 | ||||||

| Ad | 0.505 | 0.304 | 0.806 | |||||

| Op | 0.437 | 0.177 | 0.365 | 0.783 | ||||

| ESC | 0.501 | 0.172 | 0.484 | 0.263 | 0.859 | |||

| FP | 0.192 | −0.058 | 0.244 | 0.197 | 0.019 | 0.912 | ||

| EP | 0.149 | −0.123 | 0.126 | 0.416 | −0.024 | 0.443 | 0.891 | |

| OP | 0.118 | −0.179 | 0.178 | 0.278 | 0.128 | 0.599 | 0.447 | 0.933 |

| ESA | AO | Ad | Op | ESC | FP | EP | OP | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESA | ||||||||

| AO | 0.420 | |||||||

| Ad | 0.898 | 0.896 | ||||||

| Op | 0.748 | 0.394 | 0.599 | |||||

| ESC | 0.833 | 0.563 | 0.857 | 0.377 | ||||

| FP | 0.310 | 0.224 | 0.376 | 0.224 | 0.047 | |||

| EP | 0.255 | 0.366 | 0.212 | 0.526 | 0.040 | 0.566 | ||

| OP | 0.183 | 0.413 | 0.282 | 0.326 | 0.153 | 0.719 | 0.552 |

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Self Awareness→Financial Performance | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.062 | 0.090 | 0.928 |

| Achievement Orientation→Financial Performance | −0.221 | −0.221 | 0.060 | 3.654 | 0.000 |

| Adaptability→Financial Performance | 0.191 | 0.181 | 0.055 | 3.487 | 0.001 |

| Optimism→Financial Performance | 0.291 | 0.284 | 0.047 | 6.135 | 0.000 |

| Emotional Self Control→Financial Performance | −0.088 | −0.068 | 0.052 | 1.674 | 0.095 |

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Self Awareness→Employee Performance | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.055 | 0.091 | 0.927 |

| Achievement Orientation→Employee Performance | −0.197 | −0.189 | 0.056 | 3.539 | 0.000 |

| Adaptability→Employee Performance | 0.170 | 0.162 | 0.049 | 3.465 | 0.001 |

| Optimism→Employee Performance | 0.260 | 0.253 | 0.047 | 5.512 | 0.000 |

| Emotional Self Control→Employee Performance | −0.078 | −0.061 | 0.047 | 1.677 | 0.094 |

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Self Awareness→Operational Performance | 0.006 | 0.006 | 0.063 | 0.090 | 0.928 |

| Achievement Orientation→Operational Performance | −0.224 | −0.215 | 0.062 | 3.633 | 0.000 |

| Adaptability→Operational Performance | 0.194 | 0.184 | 0.056 | 3.476 | 0.001 |

| Optimism→Operational Performance | 0.295 | 0.288 | 0.049 | 6.076 | 0.000 |

| Emotional Self Control→Operational Performance | −0.089 | −0.069 | 0.053 | 1.689 | 0.092 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Strugar Jelača, M.; Bjekić, R.; Berber, N.; Aleksić, M.; Slavić, A.; Marić, S. Impact of Managers’ Emotional Competencies on Organizational Performance. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8800. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148800

Strugar Jelača M, Bjekić R, Berber N, Aleksić M, Slavić A, Marić S. Impact of Managers’ Emotional Competencies on Organizational Performance. Sustainability. 2022; 14(14):8800. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148800

Chicago/Turabian StyleStrugar Jelača, Maja, Radmila Bjekić, Nemanja Berber, Marko Aleksić, Agneš Slavić, and Slobodan Marić. 2022. "Impact of Managers’ Emotional Competencies on Organizational Performance" Sustainability 14, no. 14: 8800. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14148800