1. Introduction

All tourism destinations need to be competitive in the global tourism marketplace, even those located in rural areas which may have limited financial and human resources. Some rural towns and communities are highly dependent on the tourism industry to generate jobs and revenues for their residents. In those cases, locally-appropriate tourism is intrinsically linked to the sustainability of local communities [

1]. Rural tourism destinations and rural communities must make strategic decisions, based on knowledge generated by relevant research.

The tourism destination competitiveness (TDC) model adopts a holistic approach to identify the strengths and weaknesses of resources and capabilities endowed in and created by tourism destinations. TDC research started in the late 1990s, further developed with subsequent theoretical conceptualizations and empirical studies around 2000, and has become an enduring theme in tourism studies. After reviewing one hundred and twenty-one TDC articles between 1997 and 2018, Cronjé and Du Plessis suggested that “tourism destination competitiveness will remain a popular research topic within the tourism industry” [

2] (p. 256).

Cronjé and Du Plessis also claimed that “most [TDC] research case studies were based in Europe and therefore emphasise the need for focus on other continents as well” [

2] (p. 256). Japan is recognized as a unique and attractive tourism destination but TDC research in the country has been very scarce. Dwyer et al. [

3] measured the price competitiveness of Japan as a tourism destination but no studies which apply TDC in Japanese rural destination have been reported in the tourism literature. This paper seeks to examine the destination competitiveness of the Miyagi Zaō mountains area in the Tōhoku (northeastern) region of Japan. Stakeholder perceptions are identified from both demand and supply sides to inform a tourism strategy designed to achieve sustainable development.

The region that is the subject of the study experienced major disruptions associated with the 2011 earthquake, Tsunami and Fukushima nuclear accident and warnings of volcanic eruptions in 2015 and 2018. Zaō town located in the center of the region has an aging population and shrinking economy and relies heavily upon the tourism industry. The Zaō town government considers tourism development to be the foundation for the sustainability of the local community. Adopting an instrumentalism perspective, this study utilizes the TDC model as a tool to identify the strengths and weaknesses of tourism resources in the Miyagi Zaō region. The findings inform strategy formulation, using tourism development to sustain tourism, the host society and the local environment [

1,

4].

This article is divided into a number of sections. In the first sections, a review of research related to destination competitiveness is followed by an explanation of the purpose of the study and the approach that was adopted. The history and context of the Miyagi Zaō area and existing development strategies of the Zaō town government are discussed in the third section, and the importance of tourism to the region is identified in the fourth section. The implementation and results of the questionnaire survey are discussed before the findings and implications are presented in the final section.

3. Miyagi Zaō Mountains and Zaō Town: Understanding the Region

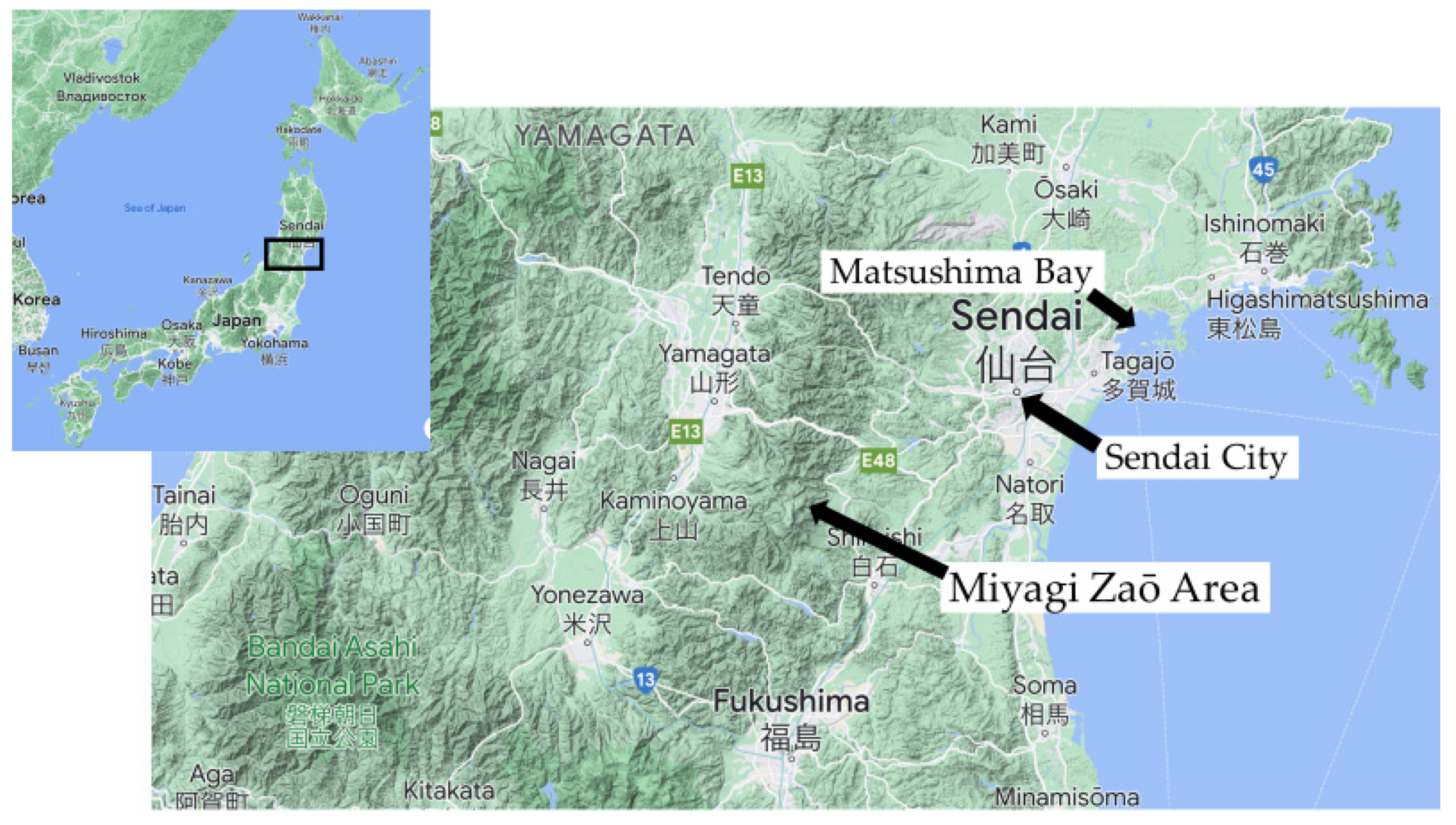

Zaō is the name of the mountains (38.141° N, 140.449° E) that lie between Miyagi and Yamagata prefectures in the northeastern (Tōhoku) region of Japan (

Figure 1). The distance from Tokyo to Miyagi Zaō is 287 km [

38] with a travelling time, by bullet train and bus, of approximately three hours. The mountains separate the Miyagi Zaō area on the Pacific Ocean side and Yamagata Zaō area on the Japan Sea side. This study focuses only on the Miyagi Zaō area. As recorded history by the Japan Meteorological Agency [

39], the Zaō volcano has erupted since 773 with the most recent eruption occurring in 1940. A crater lake, the so-called Okama (kettle), is a famous tourism attraction. Two towns, Zaō and Kawasaki, and a city, Shiroishi, are included in the Miyagi Zaō mountains area. The Zaō town is located at the center of the area.

According to the report “The Vision of Zaō Town Population” issued by the Zaō town government in 2015 [

41], the population of Zaō town was 13,172 in 2010. The website of the Miyagi prefecture showed that the population of Zaō town had declined to 11,621 in 2021 (−11.7% since 2010) [

42]. “The Vision” indicated that while the population of 65 years and over had increased from 3,676 in 2010 to 4,043 (+367) in 2015, the population, across all age groups, below 65 had decreased. The phenomenon of “shrinking and aging society” has been evident in the town. “The Vision” report suggested that a combination of tourism and agriculture industries—agritourism—could help address the declining population and assist the local economy [

41].

According to the tourism statistics of Zaō town and Miyagi prefecture governments [

41,

43], 3.8 million to 4 million people per year visited to the Miyagi Zaō area (

Figure 2). During these sixteen years, the highest and lowest number of visitors were 4.1 million in 2019 and 2.9 million in 2011. The Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011 caused considerable damage in the region and the Fukushima nuclear accident reduced visitation to the region.

In terms of overnight visitation, 592,341 people lodged in the area in 2019 with the highest number being 664,761 in 2006. The global financial crisis reduced visitor numbers in 2008 and 2009. Interestingly, several hotels and traditional Inns situated in the Miyagi Zaō area were designated as temporary shelters for people evacuated from the 2011 Tsunami disaster and the number of people registered as overnight visitors increased in 2011 and 2012. As these evacuees returned to their homes, the number decreased in 2013 and 2014. Warnings about likely eruptions of the Zaō volcano caused a decline of visiting and lodging in 2015 and 2018. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic had a major impact on tourist activity in 2020.

Statistical information of industry classification in the Zaō town illustrates the economic importance of tourism. The statistics are published every five years on the Zaō town government website. The most recent were figures for 2014, contained in the 2017 report [

44]. At this time, the number of offices in accommodation and restaurant industries (103 offices) was the second largest and accounted for 16% of the total number (653 offices) situated in the town. The largest industry was the wholesale and retail classification that owned 137 offices. This would include the tourism-related shops such as those selling souvenirs. The size of the workforce in accommodation and restaurant industries (763 people) was the second largest group and shared 14% of the total workforce (5,503 people) in the town. Manufacturing (1,302 people) was the largest sector with the wholesale and retail (661 people) the third largest. Clearly, tourism represents a major part of the local economy.

4. Tourism Resources and Development in the Miyagi Zaō

It is important to have a clear understanding of the resources that underpin tourism in the region and

Table 1 describes the resources, both endowed and created, in the Miyagi Zaō Mountain area. The natural and historical resources include the Okama crater lake, hot spas, shrines and temples, and the history of local Samurai. Although not as famous as Kyoto and Tokyo among international tourists, some of the resources of the Miyagi Zaō mountains area, especially the snow monsters, are well known throughout Japan. The sports, tourist attractions, special events and local foods are created resources that include winter sports, cycle races, a traditional dancing festival, local fruits, Soba noodle, Zaō cheese and beef [

45].

The region has sixteen hotels and traditional Japanese Inns (Ryokan in Japanese), six pensions and visitor homes and four rental cottages [

46]. Many of the hotels and traditional Japanese Inns are equipped with hot spas (Onsen in Japanese). There are thirteen restaurants, five local markets, and two souvenir shops in the Zaō town [

47]. The level of service provision has made the region an attractive destination for residents of the Tōhoku region.

As in many European countries, the development of tourism policies is a responsibility of local government and the Agriculture, Forest and Tourism Department produced “Tourism of Zaō town: Strengthening the competitiveness of hot spas and tourism industry of Zaō region” in 2017 [

48]. In the document, the government categorized tourism resources into strengths and weaknesses (

Table 2). The name recognition associated with the Zaō mountains, the Zaō dairy industry and accessibility to the region were considered to be key strengths whereas the small and decreasing number of visitors coming from other prefectures and staying overnight in the region, especially overseas visitors, and the spatial concentration of visitors, restricted to a small number of places, were regarded as weaknesses.

Attracting foreign tourists is one of objectives of the Zaō town government, as outlined in a new 10 years tourism development strategy (2018 to 2027) [

48]. Inbound tourists, especially from Taiwan and Thailand will be targeted. To do so, the government will make signs multilingual and use pictograms in the destination and hospitality industry. The strategy also emphasizes the need to enhance the destination brand of Zaō, to exploit data-driven strategy formulation, to combine various tourism resources, to attract educational or school tours and to enrich agritourism and local foods.

5. Study Method

Building of the situation analysis and information in the documents prepared by the government department, researchers at Tohoku Gakuin University sought additional data on which to base strategic recommendations. The data from qualitative interviews and a quantitative survey was gathered to provide a comparison of demand and supply perspectives. Yin [

49] recommended the combination of qualitative and quantitative data to fully understand and describe a study environment. Two experienced industry professionals; female managers of Japanese traditional Inns situated in the Miyagi Zaō mountains area, were interviewed on 27 September 2018 and a questionnaire survey was conducted with the support of Department of Agriculture Forest and Tourism of the Zaō town government. Drawing on the work of Gomezelj and Mihalič’s [

21] and Zhou et al. [

23], a list of TDC elements was submitted to the Zaō town government. Following discussions held with government officials, it was decided to retain elements that reflected the characteristics of Miyagi Zaō and were appropriate to the Japanese tourism context. Since competitiveness is a relative measurement and consistent with the approach used by Gomezelj and Mihalič [

21], respondents were required to judge five tourism destinations that compete with the Miyagi Zaō mountains area. Respondents were asked to score twenty-six TDC elements using a five-point Likert scale (1 = well below average, 3 = average, 5 = well above average).

The survey sought to gather data from visitors (demand side) and local company managers (supply side). The Zaō town government allowed us to access visitors to complete the questionnaire at designated places in 2017; at the public spa facility on 15 October and at a local festival on 29 October. Trained undergraduate students, majoring in business administration and accounting, were deployed to distribute the questionnaires and 144 were successfully completed. Due to privacy policies, our access to the list of local companies held by the government was restricted. Thus, government officers were asked to select tourism-related local companies such as hotels, restaurants, and tourism attractions from the list and to distribute 150 questionnaires to those companies. Government regulations prohibited the identification of individual businesses. Fifty-two questionnaires were returned from the companies, a response rate of 35%. The response rate (35%) from supply side is higher than Enright and Newton survey (16%) [

12], but lower than Gomezelj and Mihalič survey (41%) [

21].

7. Findings

The industry managers who were interviewed suggested that a famous, local historical figure; a Samurai named Yukimura Sanada, should feature more prominently when developing new tourism products. It was also proposed that food-related events, street performances and Japanese Bon dance festivals should be developed as new tourism attractions. A diversification strategy was advocated, rather than one relying solely on agritourism.

The questionnaire survey found that, among visitors, Sendai was considered to be the main competitor of the Miyagi Zaō mountains (

Table 5). Sendai is the largest city in the Tōhoku region with a population of one million. It attracts approximately 22 million visitors each year [

43]. It has a wide range of shopping facilities, professional sports teams (baseball, basketball and soccer), cultural and historical attractions and hosts seasonal events. The industry managers considered the neighboring Yamagata prefecture that includes destinations such as Yamagata Zaō, Kaminoyama, Tendō, Yonezawa and so forth to be the main competitor. In third place, with both visitor and industry segments, was Matsushima Bay which has a reputation across the country as being among the top three locations in Japan for the most beautiful coastal scenery [

51].

Since TDC research is essentially descriptive rather than analytic [

5], this study, in common with those of Enright and Newton [

12] and Gomezalj and Mihalič [

21], calculated the means and standard deviations of TDC elements and conducted t-tests to determine whether there was a significant difference between visitors’ and company managers’ scores. As shown in

Table 6, nature-based activities were awarded the highest scores and there was no significant difference between scores for visitors and industry representatives; 3.844 and 3.885 respectively. Both groups believed that nature-based resources offer the greatest competitive advantage for the Miyagi Zaō mountains area. Similarly, both groups ranked shopping facilities as the least competitive although the industry group gave significantly lower scores (2.607 and 1.981,

p < 0.001).

Visitors perceived safety and security, hospitality and friendliness, cleanliness and value for money as the strongest TDC elements. The high score for safety and security is noteworthy as the survey was conducted only two years after the warning about a likely volcanic eruption. This suggests that such warnings may not have a long-term impact on the appeal of the region. Only eight of the twenty-six items received scores lower than 3.0 by visitors. In addition to shopping facilities, they were well-known landmarks (2.769), exciting experience from adventures (2.817), availability of activities for children (2.831), interesting architecture (2.875), accessibility (2.974), local transportation efficiency (2.975) and facilities to interact (2.984).

The sample of company managers, representing the supply side, gave lower scores for destination competitiveness than the visitor sample. The difference was significant for many of the items especially for hospitality and friendliness, value for money of trip, variety and quality of restaurants and availability of tourist information. Relative to visitors, the company managers seem to underestimate the destination’s resources and their own capabilities to serve visitors. From both the demand and supply perspectives, well-known landmarks (2.769 and 2.118), exciting experience (2.817 and 2.24), availability of activities for children (2.831 and 2.118), interesting architecture (2.875 and 2.059), accessibility to destination (2.974 and 2.615) and facilities to interact (2.984 and 2.462) received low scores. These elements were perceived as weaknesses of the Miyagi Zaō mountains area by both sides.

In

Table 6, the consonance and dissonance of evaluations between demand and supply sides are evident. The tendency for local industry representatives to undervalue the competitiveness of their destination compared with visitors’ evaluations is reinforced. In

Table 7, a comparison is made between the findings of the survey and the self-categorization of strengths and weaknesses by the Zaō town government officials (as shown in

Table 2). The consistently high scores for nature provides a strong foundation for strategy formulation but it is also important to note the variations in the evaluations. While the government representatives considered accessibility to the destination as a strength, visitors gave it a lower score. In contrast, visitors gave a relatively high evaluation for the quality of accommodation but the government perceived visitors to have a low level of satisfaction with these services. It is noteworthy that the TDC framework helps clarify differences between visitors (demand side) and local companies (supply side) and the perceptions among government officials. This insight is of considerable value for strategy formulation.