Income, Social Capital, and Subjective Well-Being of Residents in Western China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What is the overall profile of residents’ SWB in western China?

- How do income and social capital lead to changes in SWB, respectively?

- Does social capital moderate the impact of income on SWB?

2. Review of the Literature

2.1. Income and SWB

2.2. Social Capital and SWB

3. Materials and Methods

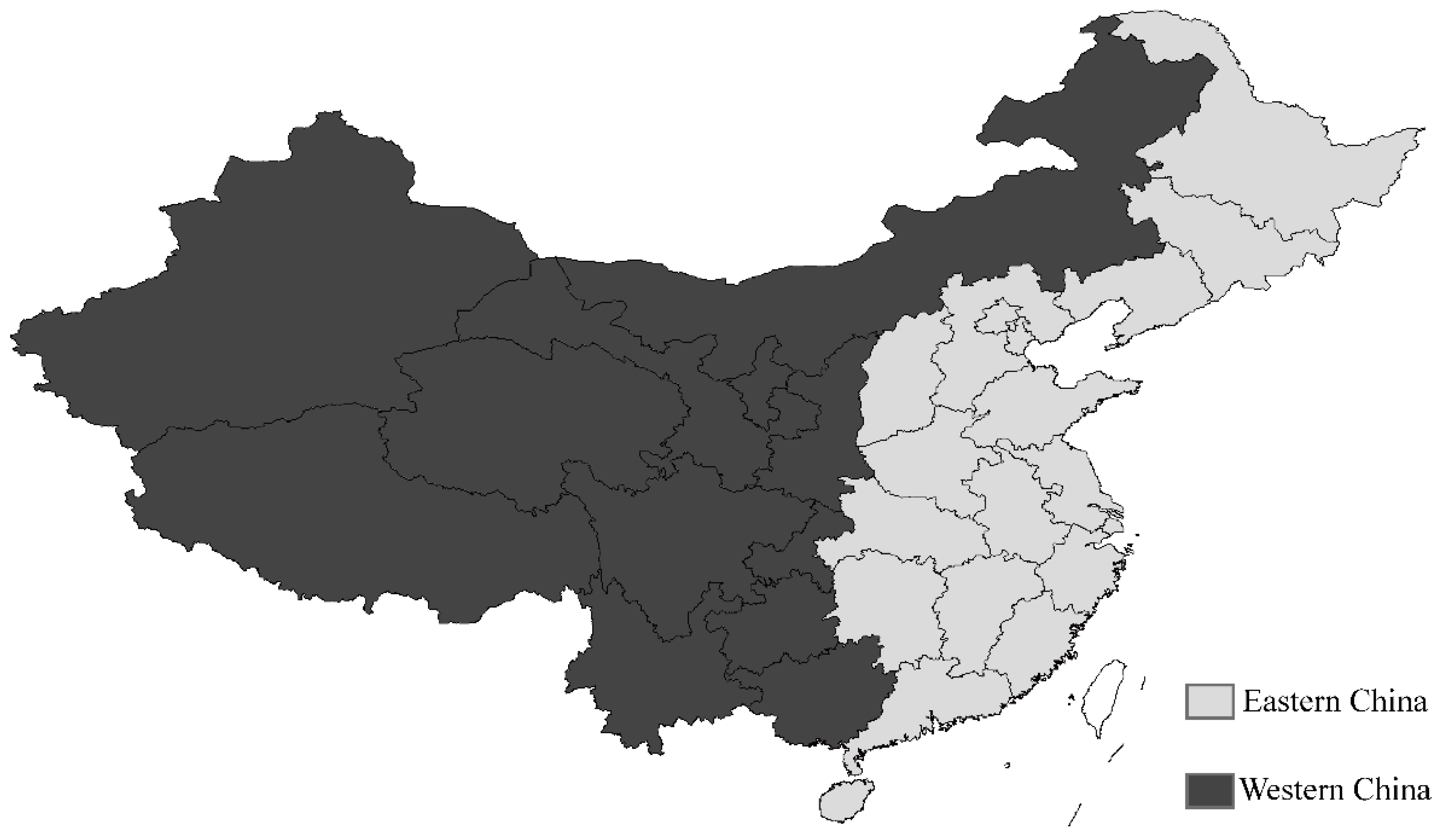

3.1. Data

3.2. Variables

3.2.1. Dependent Variables

3.2.2. Independent Variables

3.2.3. Control Variables

3.3. Analysis Strategy

4. Results

4.1. A Descriptive Statistical Analysis of the Differences in the Characteristics of Residents

4.2. Correlation between Income, Social Capital and SWB

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Information Office of the State Council. 2010 National Economic Performance [EB/OL]. 20 January 2011. Available online: http://www.scio.gov.cn/ztk/xwfb/21/index.htm (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- National Bureau of Statistics. 2010 National Economic and Social Development Statistics Bulletin [EB/OL]. 28 February 2011. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/gzdt/2011-02/28/content_1812697.htm (accessed on 6 May 2022).

- GlobeNewswire; Gallup. Chinese People’s Happiness Is Low [EB/OL]. 23 April 2011. Available online: https://world.huanqiu.com/article/9CaKrnJqULC (accessed on 8 May 2022).

- GlobeNewswire.com. 2013 Global Happiness Index Report: China Ranked 93rd [EB/OL]. 10 September 2013. Available online: https://world.huanqiu.com/article/9CaKrnJCdo6 (accessed on 10 May 2022).

- Easterlin, R.A. China’s life satisfaction, 1990–2010. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 9775–9780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Diener, E.; Suh, E.M.; Lucas, R.E.; Smith, H.L. Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychol. Bull. 1999, 125, 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.D.; Emmons, R.A.; Larsen, R.J.; Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Personal. Assess. 1985, 49, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, Z. A study on the relationship between income and happiness in China. Sociol. Res. 2011, 25, 196–219. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Xiong, M.; Su, Y. National happiness in the period of economic growth—A tracking study based on CGSS data. China Soc. Sci. 2012, 12, 82–102. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin, R.A. Does Economic Growth Improve the Human Lot? Some Empirical Evidence. In Nations and Households in Economic Growth; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974; pp. 89–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easterlin, R.A. Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1995, 27, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Lucas, R.E. Explaining Differences in Societal Levels of Happiness: Relative Standards, Need Fulfillment, Culture, and Evaluation Theory. J. Happiness Stud. 2000, 1, 41–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingdon, G.G.; Knight, J. Community, Comparisons and Subjective Well-being in a Divided Society. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2007, 64, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deaton, A.; Stone, A.A. Two happiness puzzles. Am. Econ. Rev. 2013, 103, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Inglehar, R. Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Veenhoven, R. Is happiness relative? Soc. Indic. Res. 1991, 24, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagerty, M.R.; Veenhoven, R. Wealth and Happiness Revisited: Growing National Income Does Go with Greater Happiness. Soc. Indic. Res. 2003, 64, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S.; Krueger, A.B. Economic Growth and Subjective Well-Being: Reassessing the Easterlin Paradox. In Brookings Papers on Economic Activity; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R. Post-materialism in an environment of insecurity. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1981, 75, 880–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.S. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. Knowl. Soc. Cap. 2000, 94, 17–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpert, H.; Durkheim, E.; Spaulding, J.A.; Simpson, G.; Solovay, S.A.; Mueller, J.H.; Catlin, G.E.G. Suicide: A Study in Sociology; Routledge Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan, P.; Peasgood, T.; White, M. Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. J. Econ. Psychol. 2008, 29, 94–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan, M.P.; Durlak, J.A.; Bryant, F.B. The relationship of social support to perceived control and subjective mental health in adolescents. J. Community Psychol. 1993, 21, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, R. The provisions of social relationships. In Doing Unto Others; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1974; pp. 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivaldi, E.; Bonatti, G.; Soliani, R. Objective and Subjective Health: An Analysis of Inequality for the European Union. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 138, 1279–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macků, K.; Caha, J.; Pászto, V.; Tuček, P. Subjective or Objective? How Objective Measures Relate to Subjective Life Satisfaction in Europe. Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, Y.J. Bringing Strong Ties Back in: Indirect Ties, Network Bridges, and Job Searches in China. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1997, 62, 366–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, N. Social Capital: A Theory of Social Structure and Action; Cambridge University press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Maslow, A.H. Motivation and Personality; Renmin University of China Press: Beijing, China, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y. What makes rural teachers happy? An investigation on the subjective well-being (SWB) of Chinese rural teachers. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2018, 62, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhou, A.; Zhang, M.; Wang, H. Assessing the effects of haze pollution on subjective well-being based on Chinese General Social Survey. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 235, 574–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yan, J.; Xu, Z. How does new-type urbanization affect the subjective well-being of urban and rural residents? Evidence from 28 provinces of China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Factor Loading Factor | Marks | Factor Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Size | 0.379 | Mean value | 3.25 |

| Network Density | −0.402 | Standard deviation | 1.28 |

| Top of Network | 0.945 | Min. value | −2.37 |

| Network Gap | 0.939 | Max. value | 4.61 |

| Total Resources | 0.834 | KMO value | 0.73 |

| Variable | Mean/Percentage | SD | Min | Max | Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWB | 3.17 | 0.92 | 1 | 4 | Multi-categorical variables 4 = Regular 3 = Sometimes 2 = Rarely 1 = Not |

| Regularly feel happy | 44.18% | ||||

| Sometimes feel happy | 35.93% | ||||

| Rarely feel happy | 12.33% | ||||

| Never feel happy | 7.57% | ||||

| Absolute income | 2.00 | 0.81 | 1 | 3 | Multi-categorical variables 3 = High income 2 = Middle income 1 = Low income |

| High income | 33.44% | ||||

| Middle Income | 33.4% | ||||

| Low income | 33.16% | ||||

| Relative income | 1.88 | 3.23 | 0 | 66.99 | Continuous variables |

| Social capital | 3.25 | 1.28 | 0 | 4.61 | Continuous variables |

| Network size | 34.81 | 34.92 | 1 | 300 | Continuous variables |

| Network density | 0.62 | 0.23 | 0 | 1 | Continuous variables |

| Top of network | 54.33 | 31.29 | 8 | 83 | Continuous variables |

| Network gap | 43.24 | 31.3 | 0 | 75 | Continuous variables |

| Total resources | 169.29 | 157.31 | 8 | 506 | Continuous variables |

| Region of residence | 0.62 | 0.48 | 0 | 1 | Binary variables, 0 = urban, 1 = rural |

| Gender | 0.51 | 0.49 | 0 | 1 | Binary variables, 0 = male, 1 = female |

| Age | 45.27 | 11.25 | 18 | 65 | Continuous variables |

| Age2/100 | 21.76 | 10.11 | 4.84 | 42.25 | Continuous variables, age2 denotes square of age, then divided by 100. |

| Marriage | 0.83 | 0.37 | 0 | 1 | Binary variables, 0 = unmarried, 1 = married |

| Schooling years | 8.19 | 4.52 | 0 | 19 | Continuous variables |

| Health status | 4.02 | 1.09 | 1 | 5 | Multi-categorical variables, Represents the physical health of the individual, 1 = very unhealthy to 5 = very healthy |

| Recent mood | 2.68 | 0.90 | 1 | 4 | Multi-categorical variables, Represents mental health of the individual, from 1 = very bad to 5 = very good |

| Variables | Mean | Ratio of Means | Difference of Means | t-Test | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | Rural | City/Rural | City-Rural | ||

| SWB | 3.21 | 3.14 | 1.022 | 0.07 | 3.01 ** |

| Absolute income | 18,003.08 | 9247.94 | 1.947 | 8755.14 | 18.42 *** |

| Relative income | 1.80 | 1.93 | 0.933 | −0.13 | −1.85 |

| Social capital | 3.73 | 2.97 | 1.256 | 0.76 | 26.45 *** |

| Network size | 34.28 | 35.12 | 0.976 | −0.84 | −1.03 |

| Network density | 0.56 | 0.65 | 0.862 | −0.09 | −18.71 *** |

| Top of network | 67.76 | 46.38 | 1.461 | 21.38 | 31.05 *** |

| Network gap | 52.07 | 38.01 | 1.370 | 14.06 | 19.75 *** |

| Total resources | 235.41 | 130.15 | 1.809 | 105.26 | 30.33 *** |

| Age | 45.65 | 45.04 | 1.014 | 0.61 | 2.33 * |

| Gender | 0.54 | 0.48 | 1.125 | 0.60 | 5.23 *** |

| Marital status | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.941 | −0.05 | −5.85 *** |

| Education level | 10.96 | 6.56 | 1.671 | 4.40 | 47.40 *** |

| Health status | 4.10 | 3.97 | 1.033 | 0.13 | 5.13 *** |

| Recent mood | 2.66 | 2.68 | 0.993 | −0.02 | −0.85 |

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute income | |||||

| Moderate income (=2) | −0.017 | −0.036 | −0.046 | −0.293 * | |

| Higher income (=3) | 0.128 * | 0.066 | 0.047 | −0.154 | |

| Relative income | 0.016 * | 0.015 | 0.037 ** | ||

| Social capital | 0.054 ** | 0.114 ** | |||

| Absolute income | |||||

| Absolute income × Hometown | |||||

| Moderate income | 0.268 * | ||||

| Higher income | 0.286 * | ||||

| Relative income × Hometown | −0.040 * | ||||

| Social capital × Hometown | −0.082 | ||||

| Household registration (urban = 0) | 0.021 | 0.051 | 0.032 | 0.054 | 0.043 |

| Age | −0.073 *** | −0.076 *** | −0.078 *** | −0.077 *** | −0.077 *** |

| Age2/100 | 0.079 *** | 0.083 *** | 0.084 *** | 0.084 *** | 0.084 *** |

| Gender (male = 0) | 0.119 ** | 0.135 *** | 0.141 *** | 0.143 *** | 0.151 *** |

| Marriage (unmarried = 0) | 0.490 *** | 0.489 *** | 0.490 *** | 0.491 *** | 0.493 *** |

| Years of education | 0.031 *** | 0.028 *** | 0.029 *** | 0.025 *** | 0.025 *** |

| Health status | 0.247 *** | 0.243 *** | 0.242 *** | 0.237 *** | 0.237 *** |

| Recent mood | 0.395 *** | 0.395 *** | 0.395 *** | 0.394 *** | 0.393 *** |

| Constant | 3.042 *** | 2.998 *** | 2.946 *** | 2.875 *** | 2.827 *** |

| Sample size | 7877 | 7877 | 7877 | 7877 | 7877 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.0443 | 0.0448 | 0.045 | 0.0455 | 0.0462 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Xie, J.; Zhang, X.; Yang, J. Income, Social Capital, and Subjective Well-Being of Residents in Western China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9141. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159141

Zhang J, Xie J, Zhang X, Yang J. Income, Social Capital, and Subjective Well-Being of Residents in Western China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(15):9141. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159141

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jun, Jinchen Xie, Xinyi Zhang, and Jianke Yang. 2022. "Income, Social Capital, and Subjective Well-Being of Residents in Western China" Sustainability 14, no. 15: 9141. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159141

APA StyleZhang, J., Xie, J., Zhang, X., & Yang, J. (2022). Income, Social Capital, and Subjective Well-Being of Residents in Western China. Sustainability, 14(15), 9141. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159141