Government Supports, Digital Capability, and Organizational Resilience Capacity during COVID-19: The Moderation Role of Organizational Unlearning

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Government Support

2.2. Digital Capability

2.3. Organizational Unlearning

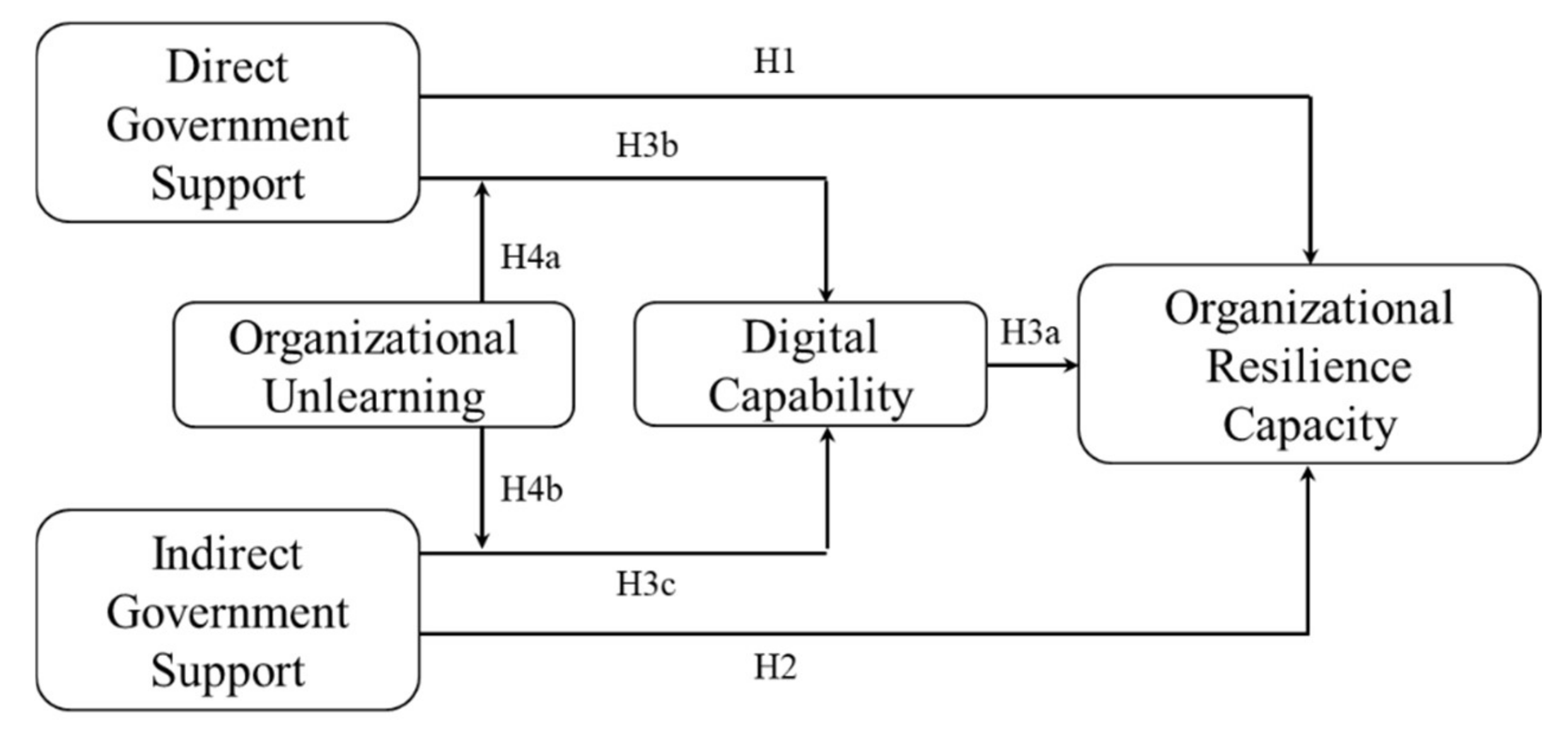

3. Theory and Hypotheses

3.1. Resource Orchestration Theory: An Integrative Theoretical Framework

3.2. Government Support and Organizational Resilience Capacity

3.3. The Mediation Role of Digital Capability

3.4. The Moderation Effect of Organizational Unlearning

4. Methodology

4.1. Sampling and Data Collection

4.2. Measures

5. Analysis and Results

5.1. Construct Validity and Reliability

5.2. Hypothesis Testing and Results

6. Discussions and Implications

6.1. Discussions of the Results

6.2. Theoretical Contributions

6.3. Managerial Implications

7. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Measurement Items, Factor Loadings, and Internal Reliabilities

| Items | Factor Loadings |

|---|---|

| To what extent do you agree with the following statements according to your company? | |

| Organizational resilience capacity (adopted from Marcucci et al., 2021) CR = 0.94; AVE = 0.81; a = 0.90 | |

| Internal Resilience: during the COVID-19 virus crisis, | |

| Our company has established brand position in the market(s) we operate, and has diversified portfolio of services/products/projects | 0.83 |

| Our company has deeply rooted risk management culture across all levels | 0.85 |

| Our company has strong financial liquidity | 0.73 |

| Our company has prompts several organizational solutions to deal with the pandemic, such as team working, creative problem solving, soft skills training | 0.78 |

| The supply chain of our company is robust, and there is a free flow of information | 0.75 |

| External resilience: during the COVID-19 virus crisis, | |

| Our business has not been influenced much | 0.81 |

| The market that we operates in has not become more uncertain and volatile | 0.85 |

| Our performance has not been influenced much by the national and international government restrictions/macroeconomic trends | 0.89 |

| Government support (adapted from Han et al., 2018; Nakku et al., 2020; Shu et al., 2016) | |

| Please indicate the extent to which in the last three years governments and agencies have: | |

| Direct government support CR = 0.94; AVE = 0.88; a = 0.91 | |

| Provided government purchase contract(s) | 0.91 |

| Favorable treatments such as tax reduction and subsidies | 0.91 |

| Provided permissions of market entry | 0.91 |

| Provide capital support such as financial resources and the permission of land using | 0.83 |

| Indirect government support CR = 0.96; AVE = 0.92; a = 0.94 | |

| Enhanced the enforcement of intellectual property protection law | 0.93 |

| Enhanced the enforcement of business transaction governance law | 0.91 |

| Offered information and explanation when new policies were formulated | 0.92 |

| Prompted the R&D collaboration between our industrial sector and the research institutions | 0.93 |

| Digital capability (adopted from Khin and Ho, 2019) CR = 0.97; AVE = 0.94; a = 0.91 | |

| Acquiring important digital technologies and mastering the state-of-the-art digital technologies | 0.92 |

| Identifying new digital opportunities | 0.94 |

| Responding to digital transformation | 0.96 |

| Developing innovative products/service/process using digital technology | 0.94 |

| Organizational unlearning (adopted from Akgun et al., 2006; Zhang and Zhu, 2021) CR = 0.96; AVE = 0.87; a = 0.84 | |

| Our company try to change beliefs regarding: | |

| Ideas of product development | |

| The features that were technically possible | 0.88 |

| The rate of market acceptance | 0.91 |

| The rate of technological improvements | 0.90 |

| Our company try to change routines regarding: | 0.84 |

| Ideas of product development | 0.80 |

| The features that were technically possible | 0.90 |

| The rate of market acceptance | 0.91 |

| The rate of technological improvements | 0.82 |

References

- Xiong, J.; Wang, K.; Yan, J.; Xu, L.; Huang, H. The window of opportunity brought by the COVID-19 pandemic: An ill wind blows for digitalisation leapfrogging. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2021, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciampi, F.; Faraoni, M.; Ballerini, J.; Meli, F. The co-evolutionary relationship between digitalization and organizational agility: Ongoing debates, theoretical developments and future research perspectives. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 176, 121383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azadegan, A.; Dooley, K. A Typology of Supply Network Resilience Strategies: Complex Collaborations in a Complex World. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2021, 57, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matt, D.T.; Pedrini, G.; Bonfant, A.; Orzes, G. Industrial digitalization. A systematic literature review and research agenda. Eur. Manag. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.Y.; Ma, L. Research on Successful Factors and Influencing Mechanism of the Digital Transformation in SMEs. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcucci, G.; Antomarioni, S.; Ciarapica, F.E.; Bevilacqua, M. The impact of Operations and IT-related Industry 4.0 key technologies on organizational resilience. Prod. Plan. Control 2021, ahead of print. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.M.; Yu, S.B.; Yang, S. Leveraging resources to achieve high competitive advantage for digital new ventures: An empirical study in China. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2022, 29, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Wu, Y.; Palacios-Marqués, D.; Ribeiro-Navarrete, S. Business networks and organizational resilience capacity in the digital age during COVID-19: A perspective utilizing organizational information processing theory. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 177, 121548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanelt, A.; Bohnsack, R.; Marz, D.; Marante, C.A. A Systematic Review of the Literature on Digital Transformation: Insights and Implications for Strategy and Organizational Change. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 1159–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindell, M.K.; Whitney, D.J. Accounting for common method variance in cross-sectional research designs. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhen, Z.; Yousaf, Z.; Radulescu, M.; Yasir, M. Nexus of Digital Organizational Culture, Capabilities, Organizational Readiness, and Innovation: Investigation of SMEs Operating in the Digital Economy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemand, T.; Rigtering, J.P.C.; Kallmunzer, A.; Kraus, S.; Maalaoui, A. Digitalization in the financial industry: A contingency approach of entrepreneurial orientation and strategic vision on digitalization. Eur. Manag. J. 2021, 39, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardolino, M.; Bacchetti, A.; Ivanov, D. Analysis of the COVID-19 pandemic’s impacts on manufacturing: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Oper. Manag. Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, C.L.; Zhou, K.Z.; Xiao, Y.Z.; Gao, S.X. How Green Management Influences Product Innovation in China: The Role of Institutional Benefits. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 133, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nakku, V.B.; Agbola, F.W.; Miles, M.P.; Mahmood, A. The interrelationship between SME government support programs, entrepreneurial orientation, and performance: A developing economy perspective. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2020, 58, 2–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredia, J.; Rubinos, C.; Vega, W.; Heredia, W.; Flores, A. New Strategies to Explain Organizational Resilience on the Firms: A Cross-Countries Configurations Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneo, S.Y.M.; Noya, S.; Melany, M.; Setiyati, E.A. The Role of Local Government in Improving Resilience and Performance of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Indonesia. J. Asian Financ. Econ. 2022, 9, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodrozic, Z.; Adler, P.S. Alternative Futures for the Digital Transformation: A Macro-Level Schumpeterian Perspective. Organ. Sci. 2022, 33, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Yang, Z.E.; Huang, K.F.; Gao, S.X.; Yang, W. Addressing the cross-boundary missing link between corporate political activities and firm competencies: The mediating role of institutional capital. Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.L.; Lin, Y.C.; Chen, W.H.; Chao, C.F.; Pandia, H. Role of Government to Enhance Digital Transformation in Small Service Business. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.B.; Xu, D.B.; Liu, H. The effects of information technology capability and knowledge base on digital innovation: The moderating role of institutional environments. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2022, 25, 720–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Kim, E.; Lee, J. Innovating by eliminating: Technological resource divestiture and firms’ innovation performance. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 123, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebauer, H.; Fleisch, E.; Lamprecht, C.; Wortmann, F. Growth paths for overcoming the digitalization paradox. Bus. Horizons 2020, 63, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredia, J.; Castillo-Vergara, M.; Geldes, C.; Gamarra, F.M.C.; Heredia, W. How do digital capabilities affect firm performance? The mediating role of technological capabilities in the new normal. J. Innov. Knowl. 2022, 7, 100171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khin, S.; Ho, T.C.F. Digital technology, digital capability and organizational performance: A mediating role of digital innovation. Int. J. Inov. Sci. 2019, 11, 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, K.S.R.; Wager, M. Building dynamic capabilities for digital transformation: An ongoing process of strategic renewal. Long Range Plann. 2019, 52, 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Th, A.; Mk, B.; Jy, C. Becoming a smart solution provider: Reconfiguring a product manufacturer’s strategic capabilities and processes to facilitate business model innovation. Technovation 2022, 102498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M.A.; Arregle, J.L.; Holmes, R.M. Strategic Management Theory in a Post-Pandemic and Non-Ergodic World. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, S.; Sarkis, J.; Hervani, A.A.; Helms, M.M. Do blockchain and circular economy practices improve post COVID-19 supply chains? A resource-based and resource dependence perspective. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2020, 121, 333–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.G.; Quayson, M.; Sarkis, J. COVID-19 pandemic digitization lessons for sustainable development of micro-and small-enterprises. Sustain. Prod. Consump. 2021, 27, 1989–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirmon, D.G.; Hitt, M.A.; Ireland, R.D. Managing firm resources in dynamic environments to create value: Looking inside the black box. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.Y.; Xi, Y.J.; Xie, J.S.; Zhao, Y.X. Organizational unlearning and knowledge transfer in cross-border M&A: The roles of routine and knowledge compatibility. J. Knowl. Manag. 2017, 21, 1580–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsou, H.-T.; Chen, J.-S. How does digital technology usage benefit firm performance? Digital transformation strategy and organisational innovation as mediators. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2021, 34, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.F.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Du, H.Y. Enterprise digitalisation and financial performance: The moderating role of dynamic capability. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2021, 34, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetindamar, D.; Abedin, B.; Shirahada, K. The Role of Employees in Digital Transformation: A Preliminary Study on How Employees’ Digital Literacy Impacts Use of Digital Technologies. In IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management; IEEE: Pickaway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.C.; Feng, J.Z.; Zhang, H.; Li, X. The effect of digital transformation strategy on performance The moderating role of cognitive conflict. Int. J. Confl. Manag. 2020, 31, 441–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, H.E.; Fey, C.F. Compatibility and unlearning in knowledge transfer in mergers and acquisitions. Scand. J. Manag. 2010, 26, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.S.; Liu, X.H.; Andersson, U.; Shenkar, O. Knowledge management of emerging economy multinationals. J. World Bus. 2022, 57, 101255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielgos, D.M.; Homburg, C.; Kuehnl, C. Digital business capability: Its impact on firm and customer performance. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2021, 49, 762–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Zhu, L. Social media strategic capability, organizational unlearning, and disruptive innovation of SMEs: The moderating roles of TMT heterogeneity and environmental dynamism. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hislop, D.; Bosley, S.; Coombs, C.R.; Holland, J. The process of individual unlearning: A neglected topic in an under-researched field. Manag. Learn. 2014, 45, 540–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Douglas, S.P.; Craig, C.S. On improving the conceptual foundations of international marketing research. J. Int. Mark. 2006, 14, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amadi-Echendu, J.; Thopil, G.A. Resilience is paramount for managing socio-technological systems during and post COVID-19. IEEE Eng. Manag. Rev. 2020, 48, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caleb, H.T.; Yim, C.K.B.; Yin, E.; Wan, F.; Jiao, H. R&D activities and innovation performance of MNE subsidiaries: The moderating effects of government support and entry mode. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 166, 120603. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, J.; Murphree, M.; Meng, S.; Li, S. The More the Merrier? Chinese Government R&D Subsidies, Dependence and Firm Innovation Performance. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 2021, 38, 289–310. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, T.; Clegg, J.; Ma, L. The conscious and unconscious facilitating role of the Chinese government in shaping the internationalization of Chinese MNCs. Int. Bus. Rev. 2015, 24, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffart, M.; Croidieu, G.; Kim, P.H.; Bowman, R. Even winners need to learn: How government entrepreneurship programs can support innovative ventures. Res. Policy 2020, 49, 104052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, O.R.; Kotabe, M. Dynamic Capabilities, Government Policies, and Performance in Firms from Emerging Economies: Evidence from India and Pakistan. J. Manag. Stud. 2009, 46, 421–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, F.; Liu, K.; Li, L.X.; Lai, K.H.; Zhan, Y.Z.; Kumar, A. Digital supply chain management in the COVID-19 crisis: An asset orchestration perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 245, 108396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, W.; Nasir, M.H.; Yousaf, Z.; Khattak, A.; Yasir, M.; Javed, A.; Shirazi, S.H. Innovation performance in digital economy: Does digital platform capability, improvisation capability and organizational readiness really matter? Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikalef, P.; Gupta, M. Artificial intelligence capability: Conceptualization, measurement calibration, and empirical study on its impact on organizational creativity and firm performance. Inform. Manag. 2021, 58, 103434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skare, M.; Soriano, D.R. A dynamic panel study on digitalization and firm’s agility: What drives agility in advanced economies 2009–2018. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 163, 120418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.Y.; Oh, K.S.; Wang, M.M. Strategic Orientation, Digital Capabilities, and New Product Development in Emerging Market Firms: The Moderating Role of Corporate Social Responsibility. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeniaras, V.; Di Benedetto, A.; Kaya, I.; Dayan, M. Relational governance, organizational unlearning and learning: Implications for performance. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2021, 36, 469–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klammer, A. Embracing Organisational Unlearning as a Facilitator of Business Model Innovation. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 25, 2150061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Lenka, U. On the shoulders of giants: Uncovering key themes of organizational unlearning research in mainstream management journals. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2021, 16, 1599–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahra, S.A.; Abdelgawad, S.G.; Tsang, E.W.K. Emerging Multinationals Venturing Into Developed Economies: Implications for Learning, Unlearning, and Entrepreneurial Capability. J. Manag. Inquiry 2011, 20, 323–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, M.C.; Nguyen, L.A. Mindful unlearning in unprecedented times: Implications for management and organizations. Manag. Learn. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, C.; Yang, J.J.; Zhang, F.; Teo, T.S.H.; Gue, W.Y. Antecedents and consequence of organizational unlearning: Evidence from China. Ind. Market Manag. 2020, 84, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cegarra-Navarro, J.-G.; Eldridge, S.; Martinez-Martinez, A. Managing environmental knowledge through unlearning in Spanish hospitality companies. J. Environ. Psychol. 2010, 30, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Lenka, U. Counterintuitive, Yet Essential: Taking Stock of Organizational Unlearning Research through a Scientometric Analysis (1976–2019). Knowl. Manag. Res. Pract. 2022, 20, 152–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgun, A.E.; Lynn, G.S.; Byrne, J.C. Antecedents and consequences of unlearning in new product development teams. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 2006, 23, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klammer, A.; Gueldenberg, S. Unlearning and forgetting in organizations: A systematic review of literature. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 860–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirmon, D.G.; Hitt, M.A.; Ireland, R.D.; Gilbert, B.A. Resource Orchestration to Create Competitive Advantage: Breadth, Depth, and Life Cycle Effects. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1390–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.T.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, G.; Song, Y.T. Exploring the Effects of Data-Driven Hospital Operations on Operational Performance From the Resource Orchestration Theory Perspective. In IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management; IEEE: Pickaway, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillmann, J.; Guenther, E. Organizational resilience: A valuable construct for management research? Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2021, 23, 7–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dong, J.Y.; Ying, Y.; Jiao, H. Status and digital innovation: A middle-status conformity perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 168, 120781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, H.; Budhwar, P.; Shipton, H.; Nguyen, H.D.; Nguyen, B. Building organizational resilience, innovation through resource-based management initiatives, organizational learning and environmental dynamism. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 808–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, T.J.; Croxton, K.L.; Fiksel, J. The Evolution of Resilience in Supply Chain Management: A Retrospective on Ensuring Supply Chain Resilience. J. Bus. Logist. 2019, 40, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoskisson, R.E.; Wright, M.; Filatotchev, I.; Peng, M.W. Emerging Multinationals from Mid-Range Economies: The Influence of Institutions and Factor Markets. J. Manag. Stud. 2013, 50, 1295–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, X.; Liu, X.H.; Xia, T.J.; Gao, L. Home-country government support, interstate relations and the subsidiary performance of emerging market multinational enterprises. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 93, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, C.; Zhang, J.J.; Zhou, Y.H. Regulatory Uncertainty and Corporate Responses to Environmental Protection in China. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2011, 54, 39–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Li, J.J.; Zhou, K.Z.; Shao, A.T. Competitive position, managerial ties, and profitability of foreign firms in China: An interactive perspective. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2009, 40, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Giudice, M.; Scuotto, V.; Papa, A.; Tarba, S.Y.; Bresciani, S.; Warkentin, M. A Self-Tuning Model for Smart Manufacturing SMEs: Effects on Digital Innovation. J. Prod. Innovat. Manag. 2021, 38, 68–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, F.; Kumar, A.; Majumdar, A.; Agrawal, R. Is artificial intelligence an enabler of supply chain resiliency post COVID-19? An exploratory state-of-the-art review for future research. Oper. Manag. Res. 2021, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesbock, F.; Hess, T.; Spanjol, J. The dual role. of IT capabilities in the development of digital products and services. Inform. Manag. 2020, 57, 103389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Quddoos, M.U.; Akhtar, M.H.; Amin, M.S.; Tariq, M.; Lamar, A. Digital technologies and circular economy in supply chain management: In the era of COVID-19 pandemic. Oper. Manag. Res. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firk, S.; Gehrke, Y.; Hanelt, A.; Wolff, M. Top management team characteristics and digital innovation: Exploring digital knowledge and TMT interfaces. Long Range Plann. 2021, 53, 102166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tortora, D.; Chierici, R.; Briamonte, M.F.; Tiscini, R. I digitize so I exist. Searching for critical capabilities affecting firms’ digital innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 129, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matt, C.; Hess, T.; Benlian, A. Digital transformation strategies. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2015, 57, 339–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.I.; Xiao, S.F. Doing good by combating bad in the digital world: Institutional pressures, anti-corruption practices, and competitive implications of MNE foreign subsidiaries. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 137, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruel, S.; El Baz, J. Disaster readiness’ influence on the impact of supply chain resilience and robustness on firms’ financial performance: A COVID-19 empirical investigation. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2021, 41, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Wang, X.; Zhu, H. NERI Index of Marketization of China’s Pprovinces 2011 Report; National Economic Research Institute; Economic Science Press: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, M.W.; Luo, Y.D. Managerial ties and firm performance in a transition economy: The nature of a micro-macro link. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 486–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, R.F.; Hult, G.T.M. Innovation, market orientation, and organizational learning: An integration and empirical examination. J. Mark. 1998, 62, 42–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis with Readings, 2nd ed.; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA; Collier Macmillan: London, UK, 1987; p. xi, 449. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1991; p. xi, 212. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Kautonen, M.; Dai, W.Q.; Zhang, H. Exploring how digitalization influences incumbents in financial services: The role of entrepreneurial orientation, firm assets, and organizational legitimacy. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 173, 121120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluge, A.; Schuffler, A.S.; Thim, C.; Haase, J.; Gronau, N. Investigating unlearning and forgetting in organizations Research methods, designs and implications. Learn. Organ. 2019, 26, 518–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean | S.D | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Firm age | 11.57 | 4.92 | -- | 0.28 ** | −0.03 | 0.01 | 0.05 | −0.07 | −0.12 | −0.02 | −0.12 | 0.03 |

| 2. Firm size | 5.85 | 1.69 | 0.28 ** | -- | −0.02 | −0.07 | 0.08 | −0.04 | −0.00 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.02 |

| 3. Indusry | 0.23 | 0.42 | −0.03 | −0.02 | -- | 0.13 | −0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.12 |

| 4. Ownership | 0.13 | 0.34 | 0.01 | −0.07 | 0.13 | -- | −0.13 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.06 |

| 5. P.P | 4.1 | 1.55 | 0.05 | 0.08 | −0.02 | −0.13 | -- | 0.04 | 0.16 * | 0.05 | 0.16 * | −0.08 |

| 6. IGS | 4.86 | 1.17 | −0.07 | −0.04 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.04 | 0.92 | 0.33 ** | 0.22 ** | 0.24 ** | 0.17 * |

| 7. DGS | 4.62 | 1.18 | −0.12 | −0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.16 * | 0.33 ** | 0.88 | 0.30 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.16 * |

| 8.ORC | 4.55 | 1.13 | −0.02 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.22 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.81 | 0.28 ** | 0.29 ** |

| 9. OU | 4.30 | 0.95 | −0.12 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.01 | 0.16 * | 0.24 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.87 | 0.32 ** |

| 10. DC | 4.77 | 1.28 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.12 | 0.06 | −0.08 | 0.17 * | 0.16 * | 0.29 ** | 0.32 ** | 0.94 |

| 11. MV | 5.22 | 4.04 | 0.04 | −.03 | −0.00 | −0.10 | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.07 | 0.04 | −0.00 | −0.06 |

| Variables | Organizational Resilience Capacity | Digital Capability | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | |

| Control Variables | |||||||

| Firm age | −0.01 (0.02) | 0.00 (0.02) | −0.01 (0.02) | 0.00 (0.02) | 0.01 (0.02) | 0.02 (0.02) | 0.02 (0.02) |

| Firm size | 0.02 (0.05) | 0.01 (0.05) | 0.01 (0.05) | 0.01 (0.05) | 0.02 (0.06) | 0.02 (0.06) | −0.01 (0.06) |

| Ownership | 0.08 (0.25) | 0.00 (0.24) | 0.03 (0.24) | −0.03 (0.24) | 0.22 (0.29) | 0.14 (0.28) | 0.14 (0.26) |

| Industry | 0.15 (0.20) | 0.12 (0.19) | 0.08 (0.19) | 0.06 (0.18) | 0.31 (0.22) | 0.27 (0.22) | 0.08 (0.21) |

| Prior performance | 0.04 (0.05) | 0.00 (0.05) | 0.06 (0.05) | 0.02 (0.05) | −0.06 (0.06) | −0.09 (0.06) | −0.11 (0.06) |

| Direct effects | |||||||

| DGS | (H1) | 0.26 *** (0.07) | (H3d) | 0.23 ** (0.07) | (H3b) | 0.18 * (09) | 0.22 * (0.09) |

| IGS | (H2) | 0.14 * (0.07) | (H3d) | 0.11 (0.07) | (H3c) | 0.17 * (08) | 0.01 (0.09) |

| DC | (H3a) | 0.25 *** (0.06) | 0.20 ** (0.06) | ||||

| OU | 0.35 *** (0.10) | ||||||

| Interactions | |||||||

| DGS × OU | (H4a) | 0.22 ** (0.07) | |||||

| IGS × OU | (H4b) | −0.14 * (0.07) | |||||

| Constant | 4.32 *** | 4.40 *** | 3.12 *** | 3.46 *** | 4.73 *** | 4.78 *** | 4.94 *** |

| Max VIF | 1.12 | 1.14 | 1.12 | 1.16 | 1.12 | 1.14 | 1.20 |

| R2 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.20 |

| ΔR2 | 0.03 *** | 0.08 *** M1 | 0.04 ** M2 | 0.06 *** | 0.12 *** | ||

| F-Value | 0.31 | 3.47 ** | 3.11 ** | 4.46 *** | 0.87 | 2.35* | 4.52 *** |

| Path | Direct Effects | Indirect Effect | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PE | CI | p-Value | PE | CI | p-Value | |

| DGS→DC→ORC | 0.235 | 0.084, 0.393 | 0.010 | 0.049 | 0.004, 0.139 | 0.033 |

| IGS→DC→ORC | 0.076 | −0.064, 0.233 | 0.277 | 0.026 | 0.002, 0.111 | 0.032 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, Y.; Yang, X.; Li, S. Government Supports, Digital Capability, and Organizational Resilience Capacity during COVID-19: The Moderation Role of Organizational Unlearning. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9520. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159520

Gao Y, Yang X, Li S. Government Supports, Digital Capability, and Organizational Resilience Capacity during COVID-19: The Moderation Role of Organizational Unlearning. Sustainability. 2022; 14(15):9520. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159520

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Yu, Xiuyun Yang, and Shuangyan Li. 2022. "Government Supports, Digital Capability, and Organizational Resilience Capacity during COVID-19: The Moderation Role of Organizational Unlearning" Sustainability 14, no. 15: 9520. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159520