Decision-Making Factors in the Purchase of Ecologic Products

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

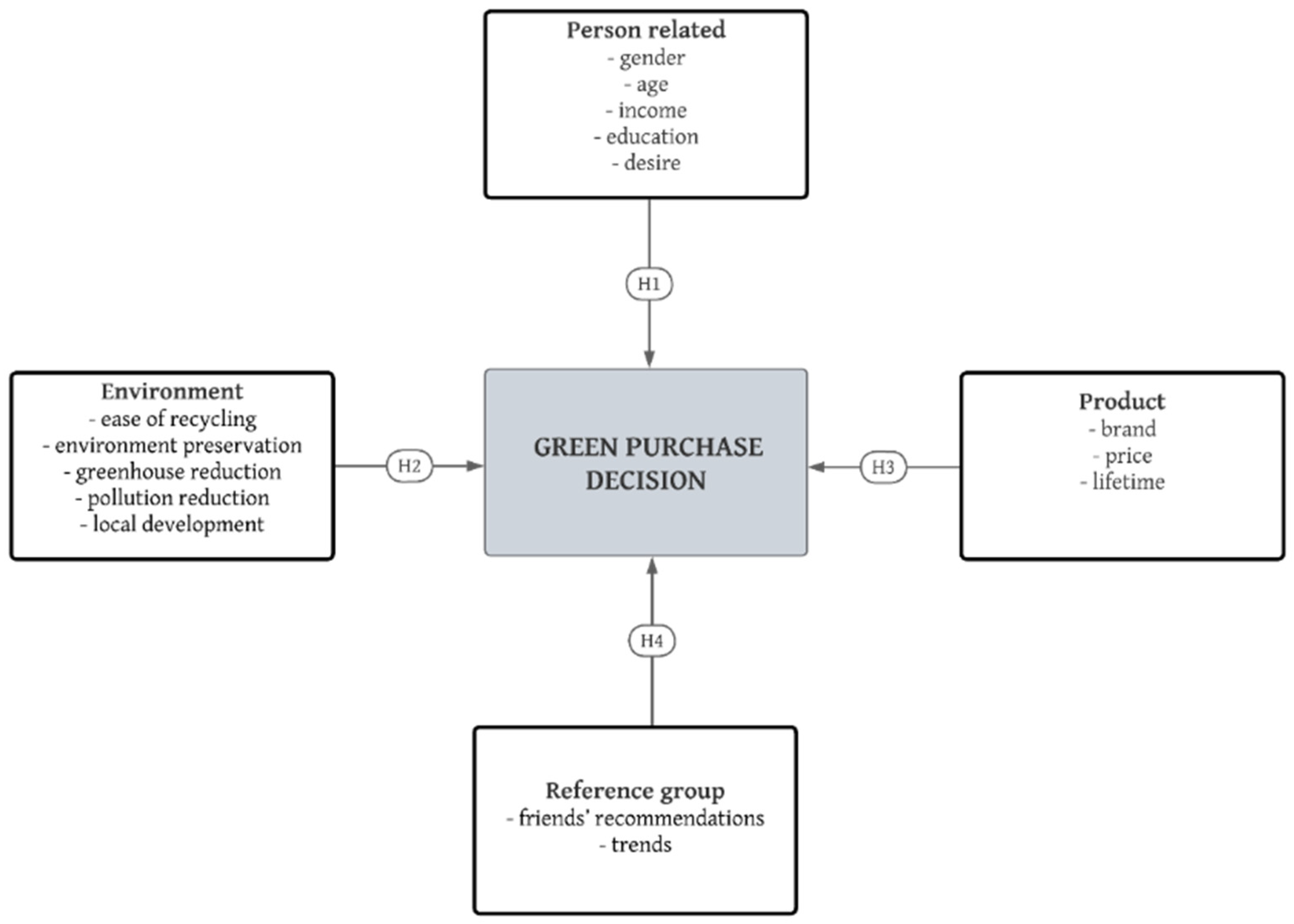

2.1. Finding Variables That Might Influence the Green Purchase Decision

2.1.1. Person-Related Factors

- (a)

- Gender

- (b)

- Age

- (c)

- Income

- (d)

- Education

- (e)

- Desire

2.1.2. Environment-Related Factors

2.1.3. Product-Related Factors

- (a)

- Brand

- (b)

- Price

- (c)

- Lifetime

2.1.4. Reference Group Variables

- (a)

- Friends’ recommendations

- (b)

- Trends

3. Research Methodology

3.1. The Sample

3.2. Descriptive Statistics of the Variables Included into the Analysis

4. Results and Discussions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Correlation Matrix

| Desire | Gender | Age | Studies | Income | Price | Brand | Quality | Fasionable | Lifetime | Friend Recomm | Local Development | Easy Recycle | Preserve Environm | Greenhouse Effect | Polution Reduction | |

| Desire | 1 | 0.19 | −0.01 | 0.17 | 0.14 | −0.11 | 0.05 | 0.22 | −0.04 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.3 | 0.37 | 0.4 | 0.35 | 0.38 |

| Gender | 1 | 0.09 | 0.02 | −0.08 | −0.08 | 0 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.11 | |

| Age | 1 | 0.04 | −0.13 | 0 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.08 | −0.03 | 0.04 | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.03 | −0.06 | ||

| Studies | 1 | 0.58 | −0.19 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.2 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.21 | 0.2 | |||

| Income | 1 | −0.24 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.1 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.2 | ||||

| Price | 1 | 0.33 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.07 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.07 | −0.06 | −0.05 | |||||

| Brand | 1 | 0.3 | 0.33 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.2 | 0.16 | 0.09 | 0.11 | ||||||

| Quality | 1 | 0.02 | 0.33 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 0.2 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.26 | |||||||

| Trends | 1 | 0 | 0.37 | 0.07 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.02 | −0.01 | ||||||||

| Lifetime | 1 | 0.15 | 0.27 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.29 | |||||||||

| Friend recomm | 1 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.09 | ||||||||||

| Local development | 1 | 0.51 | 0.66 | 0.67 | 0.57 | |||||||||||

| Easy recycle | 1 | 0.66 | 0.64 | 0.6 | ||||||||||||

| Preserve environ | 1 | 0.78 | 0.73 | |||||||||||||

| Greenhous effect | 1 | 0.75 | ||||||||||||||

| Pollution reduction | 1 |

References

- Shiel, C.; Paço, A.; Alves, H. Generativity, sustainable development and green consumer behaviour. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 245, 118865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Bock, D.; Joseph, M. Green marketing: What the Millennials buy. J. Bus. Strategy 2013, 34, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Persaud, A.; Schillo, S.R. Purchasing organic products: Role of social context and consumer innovativeness. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2017, 35, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, M.U.H.; Qureshi, Q.S.; Rizwan, M.; Ahmad, A.; Mehmood, F.; Hashmi, F.; Riaz, B.; Nawaz, A. Green Purchase Intention: An examination of customers towards Adoption of Green Products. J. Public Adm. Gov. 2013, 3, 244–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, I.; Karagouni, G.; Trigkas, M.; Platogianni, E.I. Green marketing. EuroMed. J. Bus. 2010, 5, 166–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesini, G.; Castiglioni, C.; Lozza, E. New Trends and Patterns in Sustainable Consumption: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnall, N. What the Federal Government Can Do to Encourage Green Production; Presidential Transition Series; IBM Center for the Business of Government: Washington, DC, USA, 2008; Available online: https://www.businessofgovernment.org/sites/default/files/GreenProduction.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2022).

- Karunarathna, W.R.A.D.; Naotunna, S.S.; Sachitra, K.M.V. Factors Affect to Green Products Purchase Behavior of Young Educated Consumers in Sri Lanka. J. Sci. Res. 2017, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century; Capstone Publishing: Oxford, UK, 1997; pp. 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis, P. Investigating factors influencing consumer decision-making while choosing green products. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 132, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, A.; Crane, A. Addressing Sustainability and Consumption. J. Macromark. 2005, 25, 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, T.B.; Chai, L.T. Attitude towards the environment and green products: Consumers’ perspective. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2010, 4, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughner, R.S.; McDonagh, P.; Prothero, A.; Shultz, C.J.; Stanton, J. Who are organic food consumers? A compilation and review of why people purchase organic food. J. Consum. Behav. 2007, 6, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption among young adults in Belgium: Theory of planned behaviour and the role of confidence and values. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 64, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga Junior, S.S.; da Silva, D.; Satolo, E.G.; Magalhães, M.M.; Putti, F.F.; de Oliveira Braga, W.R. Environmental concern has to do with the stated purchase behavior of green products at retail? Soc. Sci. 2014, 3, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manichelli, E.; Hersleth, M.; Almoy, T.; Naes, T. Alternative methods for combining information about products, consumers and consumers acceptance based on path modelling. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 31, 142–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamorro, A.; Rubio, S.; Miranda, F.J. Characteristics of research on green marketing. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2009, 18, 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charter, M.; Polonsky, M. Greener Marketing. A Global Perspective on Greening Marketing Practice; Greenleaf: Sheffield, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, D.; Zhao, P.; Lou, R.; Wei, H. Environmental marketing strategy effects on market-based assets. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2013, 24, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockrey, S. A review of life cycle based ecological marketing strategy for new product development in the organizational environment. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 95, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A. Green marketing for sustainable development: An industry perspective. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 23, 301–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Schellhase, R. Sustainable marketing in Asia and the world. J. Glob. Sch. Mark. Sci. 2015, 25, 195–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahnama, H.; Rajabpour, S. Identifying effective factors on consumers’ choice behavior toward green products: The case of Tehran, the capital of Iran. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 911–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peattie, K. Environmental Marketing Management: Meeting the Green Challenge; Pitman: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Peattie, K.; Charter, M. Green marketing. In The Marketing Book, 5th ed.; Baker, M., Ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ottman, J.A. Green Marketing: Opportunity for Innovation; McGraw Hill: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Polonsky, M.J. An Introduction to Green Marketing. Electron. Green J. 1994, 1, 2–11. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/49n325b7 (accessed on 30 June 2021). [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Armstrong, G. Principles of Marketing; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Soonthonsmai, V. Environmental or green marketing as global competitive edge: Concept, synthesis, and implication. In Proceedings of the EABR (Business) and ETLC (Teaching) Conference Proceeding, Venice, Italy, 4 June 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kassaye, W. Green dilemma. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2001, 19, 444–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuela, V.Z.; Manuel, P.R.; Murgado-Armenteros Eva, M.; José, T.R.F. The Influence of the Term ‘Organic’ on Organic Food Purchasing Behavior. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 81, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Luchs, M.G.; Naylor, R.W.; Irwin, J.R.; Raghunathan, R. The Sustainability Liability: Potential Negative Effects of Ethicality on Product Preference. J. Market. 2010, 74, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Braga Junior, S.S.; Da Silva, D.; Gabrile, M.L.; de Oliveira Braga, W.R. The Effects of Environmental Concern on Purchase of Green Products in Retail. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 170, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shamdasani, P.; Chon-Lin, G.; Richmond, D. Exploring green consumers in an oriental culture: Role of personal and marketing mix. Adv. Consum. Res. 1993, 20, 488–493. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, S.G.; Carvalho, H. Machado, V.C. The influence of green practices on supply chain performance: A case study approach. Transport. Res. E-Log. 2011, 47, 850–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J.; Hailes, J. The Green Consumers; Penguin Books: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Wasik, J.F. Green Marketing and Management: A Global Perspective; Blackwell Publishers Inc.: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, S.K. Green supply-chain management: A state-of the-art literature review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2007, 9, 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottman, J.A.; Stafford, E.R.; Hartman, C.L. Avoiding green marketing myopia: Ways to improve consumer appeal for environmentally preferable products. Environment 2006, 48, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, A.M.; Borchardt, M.; Vaccaro, G.L.R.; Pereira, G.M.; Almeida, F. Motivations for promoting the consumption of green products in an emerging country: Exploring attitudes of Brazilian consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, B. Environmental costs and benefits in life cycle costing. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2005, 16, 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, K.S.; Muehlegger, E. Giving green to get green? Incentives and consumer adoption of hybrid vehicle technology. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2011, 61, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borin, N.; Cerf, D.C.; Krishnan, R. Consumer effects of environmental impact in product labeling. J. Consum. Mark. 2011, 28, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahnama, H. Effect of consumers’ attitude on buying organic products in Iran. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2016, 22, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M.J.; Rosenberger, P.J. Reevaluating green marketing: A strategic approach. Bus. Horiz. 2001, 44, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dangelico, R.M.; Pontrandolfo, P. From green product definitions and classifications to the Green Option Matrix. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 1608–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triebswetter, U.; Wackerbauer, J. Integrated environmental product innovation in the region of Munich and its impact on company competitiveness. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1484–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, J.; Prothero, A. Green consumption life-politics, risk and contradictions. J. Consum. Cult. 2008, 8, 117–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chamorro, A.; Banegil, T.M. Green marketing philos.sophy: A study of Spanish firms with ecolabels. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2006, 13, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdanifard, R.; Yan, Y.K. The Concept of Green Marketing and Green Product Development on Consumer Buying Approach. Glob. J. Commer. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 3, 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Hailes, J. The New Green Consumer Guide; Simon and Schuster: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fergus, J. Anticipating consumer trends. In The Greening of Businesses; David, A.R., Ed.; The University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ottman, J. Sometimes consumers will pay more to go green. Mark. News 1992, 16, 12–120. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, S.R. Antecedents of Green Purchase Behavior: An Examination of Collectivism, Environmental Concern, and PCE. Adv. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 592–599. Available online: http://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/9156/volumes/v32/NA-32 (accessed on 30 November 2021).

- Ruzevicius, J. Environmental management systems and tolls analysis. Inžinerinė Ekon. Eng. Econ. 2009, 64, 49–59. Available online: https://inzeko.ktu.lt/index.php/EE/article/view/11610 (accessed on 15 January 2022).

- Olson, E.G. Business as environmental steward: The growth of greening. J. Bus. Strategy 2009, 30, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, C.; Taghian, M.; Lamb, P.; Peretiatkos, R. Green products and corporate strategy: An empirical investigation. Soc. Bus. Rev. 2006, 1, 144–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pickett-Baker, J.; Ozaki, R. Pro-environmental products: Marketing influence in consumer purchase decision. J. Consum. Mark. 2008, 25, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption: Exploring the consumer “attitude–behavioral intention” gap. J. Argic. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, T.; Aksoy, S.; Caber, M. The effect of environmental concern and scepticism on green purchase behaviour. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2013, 31, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadenne, D.; Sharma, B.; Kerr, D.; Smith, T. The influence of consumers’ environmental beliefs and attitudes on energy saving behaviour. Energ. Policy 2011, 39, 7684–7694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essoussi, L.H.; Linton, J.D. New or recycled products: How much are consumers willing to pay? J. Consum. Mark. 2010, 27, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laroche, M.; Bergeron, J.; Barbaro-Forleo, G. Targeting consumer who are willing to pay more for environmentally friendly products. J. Consum. Mark. 2001, 18, 503–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shellyana Junaedi, M.F. The roles of consumer’s knowledge and emotions in ecological issues. Gadjah Mada Int. J. Bus. 2007, 9, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Ghodeswar, M.B. Factors affecting consumers’ green product purchase decisions. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2015, 33, 330–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newberry, C.R.; Klemz, B.R.; Boshoff, C. Managerial implications of predicting purchase behavior from purchase intentions: A retail patronage case study. J. Serv. Mark. 2003, 17, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruna Karatu, V.M.; Nik Mat, N.K. Predictor of green purchase intention in Nigeria: The mediating role of environmental consciousness. Am. J. Econ. 2015, 5, 296–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, N.R.N.A. Awareness of eco-label in Malaysia’s green initiative. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2009, 4, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rahman, Y.J.Z. Predictors of young consumer’s green purchase behavior. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2016, 27, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. Opportunities for green marketing: Young consumers. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2008, 26, 573–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behaviour. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.; Rahman, Z. Factors Affecting Green Purchase Behaviour and Future Research Directions. Int. Strategy Manag. Rev. 2015, 3, 128–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ajzen, I. Attitudes, Personality, and Behavior, 2nd ed.; Open University Press/McGraw—Hill: Milton-Keynes, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wheale, P.; Hinton, D. Ethical consumers in search of markets. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2007, 16, 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padel, S.; Foster, C. Exploring the gap between attitudes and behaviour: Understanding why consumers buy or do not buy organic food. Brit. Food J. 2005, 107, 606–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thøgersen, J.; Ölander, F. Spillover of environment-friendly consumer behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrington, M.J.; Neville, B.A.; Whitwell, G.J. Why ethical consumers don’t walk their talk: Towards a framework for understanding the gap between the ethical purchase intentions and actual buying behaviour of ethically minded consumers. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guagnano, G.A.; Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T. Influences on attitude-behavior relationships a natural experiment with curbside recycling. Environ. Behav. 1995, 27, 699–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phipps, M.; Ozanne, L.K.; Luchs, M.G.; Subrahmanyan, S.; Kapitan, S.; Catlin, J.R.; Weaver, T. Understanding the inherent complexity of sustainable consumption: A social cognitive framework. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.R.B.; Juhdi, N. Consumer’s Perception and Purchase Intentions towards Organic Food Products: Exploring the Attitude among Malaysian Consumers. 2008. Available online: https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/35307495/consumers-perception-and-purchase-intentions-towards-organic (accessed on 10 April 2022).

- Kaufmann, H.R.; Panni, M.F.A.K.; Orphanidou, Y. Factors affecting consumer’s green purchasing behavior: An integrated conceptual framework. Amfiteatru Econ. J. 2012, 14, 50–69. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa, M. Shades of green: A psychographic segmentation of the green consumer in Kuwait using self-organizing maps. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 11030–11038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, H.B.; Panni, M.F.A.K. Consumer perceptions on the consumerism issues and its influence on their purchasing behavior: A view from Malaysian food industry. J. Leg. Ethical Regul. Issues 2008, 11, 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Boztepe, A. Green Marketing and Its Impact on Consumer Buying Behavior. Eur. J. Econ. Political Stud. 2012, 5, 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell, S.P.; Graefe, A.R. Testing a conceptual framework of responsible environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Educ. 2002, 29, 17–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, T., Jr.; Cunningham, W.H. The socially conscious consumer. J. Mark. 1972, 36, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McIntyre, R.P.; Meloche, M.S.; Lewis, S.L. National culture as a macro tool for environmental sensitivity segmentation. In Summer Educators’ Conference Proceedings; Cravens, D.W., Dickson, P.R., Eds.; American Marketing Association: Chicago, IL, USA, 1993; Volume 4, pp. 133–139. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, B.; McKeage, K. How green is my value: Exploring the relationship between environmentalism and materialism. In Advances in Consumer Research; Allen, C.T., John, D.R., Eds.; Association for Consumer Research: Provo, UT, USA, 1994; Volume 21, pp. 147–152. [Google Scholar]

- Zelezny, L.C.; Schultz, P.W. Promoting environmentalist. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezai, G.; Mohamed, Z.; Shamsudin, M.N. Malaysian consumer’s perception towards purchasing organically produces vegetable. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Business and Economics Research, Langkawi, Malaysia, 14–16 March 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Schlegelmilch, B.B.; Sinkovics, R.R.; Bohlen, G.M. Can socio-demographics still play a role in profiling green consumers? A review of the evidence and an empirical investigation. J. Bus. Res. 2003, 56, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chekima, B.; Chekima, S.; Wafa, S.A.; Wafa, S.K.; Igau, O.A.; Laison Sondoh, S., Jr. Sustainable consumption: The effects of knowledge, cultural values, environmental advertising, and demographics. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2015, 23, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tikka, P.; Kuitunen, M.; Tynys, S. Effects of educational background on students’ attitudes, activity levels, and knowledge concerning the environment. J. Environ. Educ. 2000, 31, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcury, T.A. Environmental attitude and environmental knowledge. Hum. Organ. 2000, 49, 300–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, C.; Shishime, T.; Fujitsuka, T. Sustainable Consumption: Green Purchasing Behaviours of Urban Residents in China. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Liere, K.D.; Dunlap, R.E. The social bases of environmental concern: A review of hypotheses, explanations and empirical evidence. Public Opin. Q. 1981, 44, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akehurst, G.; Afonso, C.; Martins Gonçalves, H. Re-examining green purchase behaviour and the green consumer profile: New evidences. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 972–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, C.; Taghian, M.; Lamb, P.; Peretiatko, R. Green decisions: Demographics and consumer understanding of environmental labels. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandahl, D.M.; Robertson, R. Social determinants of environmental concern: Specification and test of the model. Environ. Behav. 1989, 21, 37–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.A. Green consumers in the 1990s: Profile and implications for advertising. J. Bus. Res. 1996, 36, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straughan, R.D.; Roberts, J.A. Environmental segmentation alternatives: A look at green consumer behaviour in the new millennium. J. Consum. Mark. 1999, 16, 558–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buttel, F.; Taylor, P. Environmental sociology and global environmental change: A critical assessment. In Social Theory and the Global Environment; Redcliff, M., Benton, T., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.C.; Chen, C.W.; Tung, Y.C. Exploring the Consumer Behavior of Intention to Purchase Green Products in Belt and Road Countries: An Empirical Analysis. Sustainability 2018, 10, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henion, K.E. The effect of ecologically relevant information on detergent sales. J. Mark. Res. 1972, 9, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, J.F.; Blackwell, R.D.; Miniard, P.W. Consumer Behavior, 8th ed.; The Dryden Press Harcourt Brace College Publishers: Forth Worth, TX, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Awad, T.A. Environmental segmentation alternatives: Buyers’ profiles and implications. J. Islamic Mark. 2011, 2, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotopoulos, C.; Krystallis, A. Purchasing motives and profile of the Greek organic consumer: A countrywide survey. Br. Food J. 2002, 104, 730–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.; Saeidinia, M.; Reza, G.; Roozbeh, H.; Omid, F.; Jamshidi, D. Brand equity determinants in educational industry: A study of large universities of Malaysia. Interdiscip. J. Contemp. Res. Bus. 2011, 3, 769–781. [Google Scholar]

- Hockett, K.S.; McClafferty, J.A.; McMullin, S.L. Environmental Concern, Resource Stewardship, and Recreational Participation: A Review of the Literature; Conservation Management Institute, College of Natural Resources, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University: Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Roitner-Schobesberger, B.; Darnhofer, I.; Somsook, S.; Vogl, C.R. Consumer perceptions of organic foods in Bangkok, Thailand. Food Policy 2008, 33, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csutora, M.; Mozner, Z.V. Consumer income and its relation to sustainable food consumption-obstacle or opportunity? Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2014, 21, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Wahid, N.; Rahbar, E.; Tan, S.S. Factors influencing green purchase behavior of Penang environmental volunteers. Int. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zimmer, M.R.; Stafford, T.F.; Stafford, M.R. Green issues: Dimensions of environmental concern. J. Bus. Res. 1994, 30, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsóka, Á.; Szerényi, Z.M.; Széchy, A.; Kocsis, T. Greening due to environmental education? Environmental knowledge, attitudes, consumer behavior and everyday pro-environmental activities of Hungarian high school and university students. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 126–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownstone, D.; Bunchm, D.S.; Train, K.E. Joint mixed logit models of stated and revealed preferences for alternative-fuel vehicles. Transport. Res. B Meth. 2000, 34, 315–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rehman, Z.; Bin Dost, M.K. Conceptualizing Green Purchase Intention in Emerging Markets: An Empirical Analysis on Pakistan. In Proceedings of the 2013 WEI International Academic Conference Proceedings, Istanbul, Turkey, 14–16 January 2013; Available online: https://www.westeastinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Zia-ur-Rehman.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2022).

- Ting, C.-T.; Hsieh, C.-M.; Chang, H.-P.; Chen, H.-S. Environmental Consciousness and Green Customer Behavior: The Moderating Roles of Incentive Mechanisms. Sustainability 2019, 11, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bagozzi, R.P. The self-regulation of attitudes, intentions and behavior. Soc. Psychol. Quart. 1992, 55, 178–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Han, H.; Lockyer, T. Medical tourism attracting Japanese tourists for medical tourism experience. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2012, 29, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. The role of desires and anticipated emotions in goal-directed behaviors: Broadening and deepening the theory of planned behavior. Brit. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.J.; Lee, C.K.; Kang, S.K.; Boo, S.J. The effect of environmentally friendly perceptions on festival visitors’ decision-making process using an extended model of goal-directed behavior. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1417–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnall, N.; Vazquez-Brust, D. Why consumers buy green? In Green-Growth: Managing the Transition to Sustainable Capitalism; Vazquez-Brust, D., Sarkis, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 287–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, W.; Hwang, K.; McDonald, S.; Oates, C.J.J. Sustainable consumption: Green consumer behaviour when purchasing products. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisander, J. Motivational complexity of green consumerism. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2007, 31, 404–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oates, C.; McDonald, S.; Alevizou, P.; Hwang, K.; Young, W.; McMorland, L. Marketing sustainability: Use of information sources and degrees of voluntary simplicity. J. Mark. Commun. 2008, 14, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamberg, S.; Moser, G. Twenty years after Hines, Hungerford and Tomera: A new meta-analysis of psycho-social determinants of proenvironmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Licata, J.W.; McKee, D.; Pullig, C.; Daughtridge, C. The recycling cycle: An empirical examination of consumer waste recycling and recycling shopping behaviors. J. Public Policy Mark. 2000, 19, 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessami, H.Z.; Yousefi, P. Investigation of major factors influencing green purchasing behavior: Interactive approach. Eur. Online J. Nat. Soc. Sci. 2013, 2, 584–596. [Google Scholar]

- Aman, A.H.L.; Harun, A.; Hussein, Z. The Influence of Environmental Knowledge and Concern on Green Purchase Intention the Role of Attitude as a Mediating Variable. Br. J. Arts Soc. Sci. 2012, 7, 145–167. [Google Scholar]

- Said, A.M.; Ahmadun, F.R.; Paim, L.; Masud, J. Environmental concerns, knowledge and practices gap among Malaysian teachers. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2003, 4, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aracıoğlu, B.; Tatlıdil, R. Effects of environmental consciousness over consumers’ purchasing behavior. Ege Acad. Rev. 2009, 9, 435–461. [Google Scholar]

- Siddique, Z.R.; Hossain, A. Sources of Consumers Awareness toward Green Products and Its Impact on Purchasing Decision in Bangladesh. J. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 11, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Thogersen, J.; Jorgensen, A.; Sandager, S. Consumer decision-making regarding a “green” everyday product. Psychol Mark. 2012, 29, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owusu, V.; Anifori, M.O. Consumer willingness to pay a premium for organic fruit and vegetable in Ghana. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2013, 16, 67–86. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, P.; Zeng, Y.; Fong, Q.; Lone, T.; Liu, Y. Chinese consumers willingness to pay for green- and eco-labeled seafood. Food Control 2012, 28, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thogersen, J. Green shopping: For selfish reasons or the common good? Am. Behav. Sci. 2011, 55, 1052–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banyte, J.; Brazioniene, L.; Gadeikiene, A. Investigation of green consumer profile: A case of Lithuanian market of eco-friendly food products. Econ. Manag. 2010, 15, 374–383. Available online: https://etalpykla.lituanistikadb.lt/object/LT-LDB-0001:J.04~2010~1367177972840/J.04~2010~1367177972840.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- American Marketing Association, Branding. Available online: https://www.ama.org/topics/branding/ (accessed on 15 April 2022).

- Chen, Y.S. The drivers of green brand equity: Green brand image, green satisfaction, and green trust. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, F.Z.; Mirza, A.A.; Aftab, A.; Asghar, B. Consumer Green Behaviour Toward Green Products and Green Purchase Decision. Int. J. Multidiscip. Sci. Eng. 2014, 5, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Irandusth, M.; Roozbahani, M.T. The role of green advertisements in green purchase intention. Kuwait Chapter Arab. J. Bus. Manag. Rev. 2014, 3, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, X. What affects green consumer behavior in China? A case study from Qingdao. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 63, 143–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aertsens, J.; Mondelaers, K.; Verbeke, W.; Buysse, J.; Van Huylenbroeck, G. The influence of subjective and objective knowledge on attitude, motivations and consumption of organic food. Brit. Food J. 2011, 113, 1353–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eze, U.C.; Ndubisi, N.O. Green Buyer Behavior: Evidence from Asia Consumers. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 2013, 48, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Enhance green purchase intentions: The roles of green perceived value, green perceived risk, and green trust. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lobo, A. Organic food products in China: Determinants of consumers’ purchase intentions. Int. Rev. Retail. Distrib. Consum. Res. 2012, 22, 293–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondelaers, K.; Verbeke, W.; Van Huylenbroeck, G. Importance of health and environment as quality traits in the buying decision of organic products. Br. Food J. 2009, 111, 1120–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ewing, G. Altruistic, egoistic, and normative effects on curbside recycling. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 733–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nation Environment Programme (UNEP); United Nation Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Is the Future Yours? Research Project on Youth and Sustainable Consumption; UNEP/UNESCO: Paris, Franch, 2001; pp. 7–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kianpour, K.; Anvari, R.; Jusoh, A.; Othman, M.F. Important Motivators for Buying Green Products. Intang. Cap. 2014, 10, 873–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, H.A.; Oerlemans, L.; van Stroe-Biezen, S. Social influence on sustainable consumption: Evidence from a behavioural experiment. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2013, 37, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsarenko, Y.; Ferraro, C.; Sands, S.; McLeod, C. Environmentally conscious consumption: The role of retailers and peers as external influences. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2013, 20, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, K.Y.H. Internal and external barriers to eco-conscious apparel acquisition. Int J. Consum. Stud. 2010, 34, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. The green purchase behavior of Hong Kong young consumers: The role of peer influence, local environmental involvement, and concrete environmental knowledge. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2010, 23, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoyer, W.D.; Macinnis, D.J. Consumer Behavior, 4th ed.; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Daido, K. Risk-averse agents with peer pressure. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2004, 11, 383–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dholakia, U.M.; Bagozzi, R.P.; Pearo, L.K. A social influence model of consumer participation in network- and small-group-based virtual communities. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2004, 21, 241–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalas, J.E.; Bettman, J.R. Self-construal, reference groups and brand meaning. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grier, S.A.; Deshpande, R. Social dimensions of consumer distinctiveness: The influence of social status on group identity and advertising persuasion. J. Mark. Res. 2001, 38, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griskevicius, V.; Tybur, J.M.; Bergh, B.V. Going green to be seen: Status, reputation, and conspicuous conservation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2010, 98, 392–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Park, J.; Ha, S. Understanding pro-environmental behaviour: A comparison of sustainable consumers and apathetic consumers. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2012, 40, 388–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mee, N.; Clewes, D. The influence of corporate communications on recycling behavior. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2004, 9, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, J. Internet use and environmental attitudes: A social capital approach. In The Environmental Communication Yearbook; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Volume 3, pp. 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.; Paladino, A. Eating clean and green? Investigating consumer motivations towards the purchase of organic food. Australas. Mark. J. 2010, 18, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakiridou, E.; Boutsouki, C.; Zotos, Y.; Mattas, K. Attitudes and behaviour towards organic products: An exploratory study. Int. J. Retail Distrib. 2008, 36, 158–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, D.; Sibony, O.; Sunstain, C.R. Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment; Little, Brown Spark: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Indicator | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Person Related | |

| age | This variable is related to the respondent’s birth year. We split the database into four groups. Born before 1965 (graded 1), between 1966–1979 (graded 2), between 1980–1994 (graded 3) and after 1995 (graded 4). |

| gender | It is a dummy variable. The variable takes value 1 if the respondent is female and 0 if male. |

| studies | The variable takes into account the respondent’s answer regarding the last form of education that she or he finished. These were primary school (graded 1), high school (graded 2), Bachelor’s (graded 3), Master’s (graded 4) or PhD (graded 5). |

| income | This variable measures monthly income. The respondents were asked to point out in which interval best fits their average monthly income (less than 1.500 lei (graded 1), between 1500 and 2500 lei (graded 2), between 2500 and 3500 lei (graded 3), between 3500 and 4500 lei (graded 4), between 4500 and 5500 lei (graded 5), or over 5.500 lei (graded 6)). |

| desire | This variable measures the desire to buy ecological products on a scale from 1 to 5, where 1 is related to never had the desire to buy ecological products and 5 is related to a very high chance of buying ecological products. |

| Product Related | |

| price | The variable measures the respondent’s opinion regarding the ecological products price. The scale is from 1 to 5, where 1 means not important and 5 means very important. |

| brand | The variable measures the respondent’s opinion regarding the ecological products brand. The scale is from 1 to 5, where 1 means not important and 5 means very important. |

| quality | The variable measures the respondent’s opinion regarding the ecological products quality. The scale is from 1 to 5, where 1 means not important and 5 means very important. |

| lifetime | The variable measures the respondent’s opinion regarding the ecological products lifetime. The scale is from 1 to 5 where 1 means not important and 5 means very important |

| Reference Group | |

| trends | The variable measures the respondent’s opinion regarding if the ecological products is fashionable. The scale is from 1 to 5, where 1 means not important and 5 means very important. |

| friend recommendations | The variable measures the respondent’s opinion regarding if the ecological product is recommended by a friend. The scale is from 1 to 5, where 1 means not important and 5 means very important. |

| Environmental | |

| local development | The variable measures the respondent’s opinion regarding if the ecological products can help local development. The scale is from 1 to 5, where 1 means not important and 5 means very important. |

| easy recycle | The variable measures the respondent’s opinion regarding if the ecological products can be easily recycled. The scale is from 1 to 5, where 1 means not important and 5 means very important. |

| preserve environment | The variable measures the respondent’s opinion regarding if the ecological products can preserve the environment. The scale is from 1 to 5, where 1 means not important and 5 means very important. |

| greenhouse effect | The variable measures the respondent’s opinion regarding if the ecological products can help reduce the greenhouse effect. The scale is from 1 to 5, where 1 means not important and 5 means very important. |

| pollution reduction | The variable measures the respondent’s opinion regarding if the ecological products can reduce the pollution. The scale is from 1 to 5, where 1 means not important and 5 means very important. |

| Indicator (%) | Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Very Often |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decision | 2.62% | 24.48% | 37.05% | 25.46% | 10.38% |

| Desire | 3.06% | 25.46% | 11.58% | 34.43% | 25.46% |

| Opinion | Average Opinion |

|---|---|

| Ecological products are expensive. | 4.00 |

| I am not interested in the environment. | 2.18 |

| I cannot do anything to improve the environment. | 2.15 |

| It is my responsibility to protect the environment. | 2.38 |

| Ecological products protect more the environment than other products. | 3.72 |

| I do not know what an ecological product is. | 1.79 |

| It is hard to identify ecological products in stores. | 2.58 |

| It is the Government responsibility to protect the environment. | 3.24 |

| It is the companies’ responsibility to protect the environment. | 3.33 |

| The ecological products have a low quality and are only based on “marketing”. | 2.60 |

| Ecological products are good for my health. | 4.12 |

| Opinion | Average Opinion |

|---|---|

| I buy only food-related ecological products. | 3.29 |

| I buy only cleaning-related ecological products. | 2.46 |

| I buy only hygiene-related ecological products. | 2.92 |

| I buy only ecological products only if I have time for shopping. | 2.90 |

| I buy only ecological products only if I can afford. | 3.72 |

| I inform myself what ecological product to buy. | 3.13 |

| I decide to buy ecological product according to the information I find in stores. | 3.14 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| age | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.019 | −0.02 |

| (−1.71) * | (−1.67) * | (−1.36) | (−1.41) | |

| gender | 0.001 | 0.001 | −0.004 | 0.0004 |

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (−0.18) | (0.01) | |

| studies | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.054 | 0.05 |

| (5.22) *** | (5.19) *** | (5.32) *** | (5.29) *** | |

| desire | 0.18 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.18 |

| (13.85) *** | (13.87) *** | (13.27) *** | (13.84) *** | |

| price | −0.068 | −0.069 | −0.067 | −0.067 |

| (−5.63) *** | (−5.71) *** | (−5.65) *** | (−5.78) *** | |

| brand | 0.025 | 0.029 | 0.022 | 0.028 |

| (2.01) ** | (2.28) ** | (1.79) ** | (2.20) ** | |

| quality | 0.02 | 0.019 | 0.021 | 0.017 |

| (1.17) | (1.14) | (1.27) | (0.099) | |

| trends | 0.004 | 0.006 | −0.005 | 0.005 |

| (0.35) | (0.55) | (−0.46) | (0.46) | |

| lifetime | −0.027 | −0.026 | −0.033 | −0.025 |

| (−2.15) ** | (−2.13) ** | (−2.66) ** | (−2.01) ** | |

| friends’ recommendations | 0.005 | 0.016 | 0.006 | 0.005 |

| (0.47) | (0.147) | (0.60) | (0.517) | |

| local development | 0.036 | 0.025 | 0.036 | 0.042 |

| (2.74) *** | (1.73) *** | (3.13) *** | (3.50) *** | |

| easy recycle | 0.068 | |||

| (5.62) *** | ||||

| preserve environment | 0.04 | |||

| (3.26) *** | ||||

| greenhouse effect | 0.06 | |||

| (5.11) *** | ||||

| pollution reduction | 0.041 | |||

| (3.11) *** | ||||

| R-squared number of observations | 38.31% | 39.34% | 39.70% | 38.25% |

| 915 | 915 | 915 | 915 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ciobanu, R.; Țuclea, C.-E.; Holostencu, L.-F.; Vrânceanu, D.-M. Decision-Making Factors in the Purchase of Ecologic Products. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9558. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159558

Ciobanu R, Țuclea C-E, Holostencu L-F, Vrânceanu D-M. Decision-Making Factors in the Purchase of Ecologic Products. Sustainability. 2022; 14(15):9558. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159558

Chicago/Turabian StyleCiobanu, Radu, Claudia-Elena Țuclea, Luciana-Floriana Holostencu, and Diana-Maria Vrânceanu. 2022. "Decision-Making Factors in the Purchase of Ecologic Products" Sustainability 14, no. 15: 9558. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159558