1. Introduction

As smartphone applications are emerging on the market everywhere in the world, it is worth examining their impact in Romania, Dracula’s brand region, where the smartphone phenomenon development is supported by internet connection speeds which are considerably higher here than in many other countries. Tourist-oriented applications such as Airbnb, Booking, Hostelbookers or Hostelworld are demonstrating humans’ affinity for objective online reviews and rating systems [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Then, transport-related apps such as Skyscanner are offering precise search results in an efficient connectivity between international low-cost and standard flights, rapidly adapting to travelers’ needs [

6]. Ryan [

7] states that people are able to create their own future travel plans in the current virtual and augmented reality context. Moreover, the Facebook and Instagram social networking apps are spreading tourism information, influencing travel decisions and behavior [

8,

9,

10]. Geomedia comprises all the internet- and social-media-connected data that refer to a geographical place, digitally transformed and viewed as a Geosystem [

11].

Romania’s rural Geosystems present a real potential for tourism development, being less accessible and different from others. Their unique attributes can be identified in the ancient history, culture, well preserved traditions and exquisite landscapes that are yet to be discovered. According to Geomedia’s methodology, the Geosystems’ unique attributes receive the maximum relative weight in the multi-criterion analysis approach due to the unusual historical facts or legends [

11]. Romania’s rural communities are characterized today by a poverty phenomenon that has represented an unrecognized and unsolved problem for the past 30 years. The fact that not a single motorway to cross the country from west to east has been built makes the Romanian road network one of the most dangerous in the world. After the 1989 overthrow of the communist government, Romanian rural workers were constantly emigrating to Western European countries in desperate survival attempts. Millions departed to Italy and Spain in search for a better life, generating the second-highest emigration growth rate after Syria [

12,

13]. Smartphone communication technologies constitute the virtual linkage to those who remained. Currently, freely available social media applications such as WhatsApp, Skype or Facebook are widely used in rural Romania, which benefits from a good internet network. The quality of local inhabitants’ mobile phones increased, gradually adapting to their communication needs [

14]. Nakano et al. [

15] emphasized the importance of social and geographical networks in the adoption of new technologies by local peasants.

After Buhalis and Law [

16], the chief factor in smartphone applications’ development is represented by the increasing number of tourists who chose to act independently from travel packages offered by agencies. They are visitors to rural Romania, which is not present as an attractive destination in the foreign tourist agencies’ offers [

17]. Schwanen and Kwan [

18] observed tourists’ options change from a location-based connectivity to a personal inter-human connection in terms of smartphone applications’ use. Smartphone apps tourism concept was generated by travelers’ permanent interest in modern technology’s applicability to their leisure activity planning, designing and management. It is offering new opportunities for yet unknown tourist destinations.

Smartphone applications’ role in tourism development is not based purely on technical knowledge [

19]. They can illustrate the Romanian rural space in a different way, identifying creative life perspectives for its inhabitants. This research envisions the smartphone applications as a new skill in the rural villagers’ tool kit that can and will be used for the sustainable development of their own community. A Geosystem-theoretic formulation was used for the real portrayal of villages’ geographical space and their interacting components. The theory is constructed on smartphone phenomena to explain the major changes in today’s Geosystems experiences, to initiate digital transformation in rural Romania and to predict future development opportunities. The smartphone applications’ constant advancements are forcing us to adapt to the new technological evolution. The geographical space is not represented through the classic globe anymore: It is inside our smartphones, which our kids are using to better visualize the world’s wonders, to send geo-located photos, and to create and communicate visiting experiences [

20].

Various writers have examined the smartphone’s role in the tourism issue, for instance, Wang et al. [

10] stated that restrictions regarding time and location were removed by smartphones users, enabling people to organize meetings with acquaintances from other locations during the ‘course of tourism’. Dickinson et al. [

21] exposed how the special apps on smartphones can coordinate travel activities through the smartphone’s sharing and internet access, changing the nature of travel planning and organization. Martínez-Graña et al. [

22] have examined the importance of smartphone applications in tourism, showing that modern technologies and avant garde applications are providing information, as well as helping to preserve and disseminate the local natural and cultural heritage. The study results of Meng et al. [

23] on smartphone users suggest quite a significant correlation between phones’ photo–video camera features and the probability of using mobiles during travelling activities. In addition, offline map applications proved to be very practical for orientation purposes.

Moreover, new travel destinations quickly arise on smartphone apps menus, enhancing the collaboration between users who are looking to disseminate the information provided by several tourist locations. There is a large proportion of tourists involved in travel experience sharing, rapidly posting photos or short movies on social networks such as Facebook or Instagram [

8,

9]. Wang et al. [

10] argued that smartphone apps used for travel occasions are more related to those functions that permit the sharing of their trip experiences.

Smartphone applications developed for travel should focus on increasing the quality of the photo–video materials while also making sure that the incorporated Global Positioning System (GPS) is activated and a high transfer internet speed is available. Publicity policies for travel apps should be oriented especially to the smartphone users who are using these photos, video, and map orientation functions [

23].

Voda et al. [

20] state that our local Geosystem representation evolved from old paper maps to smartphone geo-applications because of the advancements in Geomedia tools, enhancing rural villages’ image. This article used Geomedia methodology to analyze smartphone applications’ capabilities in the inception process of future tourist sites. The research will demonstrate that the Airbnb smartphone app represented one of the most suitable and adaptive application for locals and visitors alike. It is trustable because of the secured tourism actor-identification procedures and reliable because of the reviewer rating system. Gupta et al. [

24] stated that getting and keeping excellent ratings led to higher tourist demand, to the benefit of local communities.

Guttentag [

25] predicted the rise of Airbnb’s new smart tourism approach constructed with modern technologies, explaining it through the concept of disruptive innovation theory. Our study will show the sudden availability of less known Romanian rural touristic resources, inaccessible before the development of smartphones’ sharing opportunities. Ert et al. [

26] found that Airbnb hosts’ photographs substantially contributed to the ‘sharing economy’ platform’s trust development and fast adaptation to the new smart tourism market transformation. Tussyadiah and Pesonen’s [

27] research suggested that the Airbnb accommodation system’s efficiency is based on ‘cost savings’ and ‘social relationships with local community’. Roelofsen and Minca [

28] reflected on how the idea of Airbnb hospitality is quantified in notions such as care and belonging. Currently, Airbnb is considered the world’s leader in providing peer-to-peer accommodations [

29,

30].

An assessment will first be made regarding smartphone applications’ relevance in remote Romanian rural communities, as well as on the tourist facilities’ visualization opportunities. Finally, the availability of rural Romania’s place-related information will be evaluated. The subject of peasants’ global digital transformation will stimulate further research on the Romanian rural communities’ Geosystems [

20]. This study aims to demonstrate that the smartphone applications implemented in Romanian remote villages are and will contribute to the self-sustainable development of local tourism resources for the rural communities’ benefit. This research makes two-fold contributions. Theoretically, this study enriches the relevant content regarding the link between technological innovation and tourism development, especially in the planning of rural tourism. Practically, this study can provide reference for policymakers who expect to achieve a self-sustainable development of local tourism resources for rural communities’ benefit in Romania.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 introduces the main methods and materials.

Section 3 presents the main results and analyzes the reasons.

Section 4 compares the main findings to the extant literature and clarifies the literature contributions.

Section 5 draws conclusions, provides recommendations and summarizes the drawbacks.

2. Materials and Methods

Various materials that dealt with the Transylvanian rural community were analyzed, especially local geographical monographies, travel guides elaborated by Lonely Planet and documentaries such as the Wild Carpathia series produced by Charlie Ottley [

31,

32]. Geomedia methodology was used for the assessment of the potential for digital transformation and the identification of rural needs. Data collection was based on the local geographical information systems and their virtual representation online. Using Waze’s community-based GPS and Garmin in Reach’s satellite technology, the collected data and tracking system of Romanian locations were validated. Google Maps, Google Earth, INIS Viewer and social media internet platforms were utilized to evaluate and analyze research criterion datasets. Multi-criteria decision making was used to set the number of considered alternatives and criterions. The relative weight of each alternative (Viscri, Cund, Bagaciu, Baita and Raven’s Nest) was set according to the specific criterion’s relative weight (rw): The unique attributes (100–0.250), the innovation diffusion (90–0.225), the georeferenced illustrations (80–0.200), inhabitants’ Geomedia competence (70–0.175) and Geomedia access (60–0.150). Then, the alternatives were prioritized based on the five criterions, and the final score of each Geosystem’s effectiveness was obtained. Two types of scores were used: The relative weight for each criterion and the relative weight for each alternative for each criterion [

33].

The communities’ online virtual presence is reflected by the georeferenced illustration criterion, which was evaluated considering 266 geo-tagged Facebook posts and 425 georeferenced Google images. Various online materials that dealt with the Romanian rural community were analyzed, especially local photos, geo-historical data, travel images and YouTube videos. Geomedia competence (70 rw) and Geomedia access (60 rw) criterions were focused on the adaptation process of smartphone applications by rural inhabitants (103 respondents) based on good internet connections and Geomedia access (Facebook, 2017; Wild Carpathia, 2017). The unique attributes have the maximum relative weight (rw) of 100–0.250. The innovation diffusion criterion received a 90 rw value due to the fact that it reflects the geosystem’s capacity to become a part of the transformative networks (

Table 1). The highest criterion weight was given to t Criterion 3 (unique attributes score) followed by Criterion 4 (innovation diffusion), Criterion 5 (georeferenced illustration), Criterion 2 (Geomedia competence) and Criterion 1 (access to Geomedia).

Taking into account that internet mobile data are widely available, our research was designed to clarify the smartphone applications potential of rural Romania. A significant growth in Facebook and WhatsApp users was noticed, and gradually increasing number of Airbnb users registered [

8,

34,

35]. The modern smartphone applications such as Airbnb, Hostelbookers and Hostelworld that are combining search engine visibility with location (Google Maps) and communication tools (Facebook/WhatsApp) have been gradually adopted in rural Romania [

20]. The significant correlations between the internet rating and reviewing systems were analyzed and identified as the best solutions for rural Romania’s community-based tourism development: Responsible tourists write pertinent opinions about places visited and rate the host’s offered accommodation. Furthermore, the study focused on the Geomedia methodological approach because the georeferenced illustrations and the innovation diffusion criterions considerably influence tourists’ determination to choose a specific location [

2,

20]. Serra Cantallops and Salvi [

36] explored the effect of internet word-of-mouth on tourists’ commitment, proving its influence on tourists’ preference for accommodation services.

On-site observations were carried out, particularly in the villages of Cund, Bagaciu, Baita, Raven’s Nest and Viscri, which were considered the alternatives (

Table 2).

Each alternative received a relative score for every criterion. For example, the Bagaciu alternative received different scores for each of the criterions. Its relative weight reflected its importance compared to other alternatives considering the criterion analyzed. It is the less functional alternative. The village of Cund, on the other hand, is number one in the ranking because of more efficient innovation diffusion and for having the highest unique attributes score.

Remotely located on the main Transylvania river tributaries’ upper valleys, each of the chosen study sites presents difficult access possibilities due to bumpy gravel roads. Cund and Bagaciu are spread on two parallel Tarnava Mica river affluents. Viscri and Baita are characterized by unique old houses and well-preserved traditional customs. The Cozy House from Baita village was used to display an experimental set-up of the Airbnb system’s implementation, being the best example for smartphone apps’ role in rural tourism development [

1]. Viscri emphasized the innovation diffusion criterion’s efficiency with its exquisite fortified Saxon church and traditional restored houses as unique attributes. Mihai Eminescu trust fund experiments in Viscri suggest that local inhabitants’ education might constitute the main factor in rural tourism development [

37]. The visual data coding was performed for the understanding of the rural Geosystems’ inception processes. The scores of each alternative and each criterion were used to prioritize the alternatives (

Table 3) [

20,

33].

The unique attributes are considered the most important criterion among the five other criteria. The scores prioritized the village of Cund, closely followed by Raven’s Nest. The access to Geomedia represents the less important criterion due to the tourists’ access to the internet through their SIM cards.

A total of 36 field trips with an average duration of three days were carried out between 2016–2021 in order to explore the link between virtual village representation and the rural reality. Smartphone applications’ complex tools and abstract concepts were presented to 103 Romanian rural inhabitants. Drawings, analogies and props were used in order to facilitate an understanding of the technical concepts by the local respondents. Java objects inside the Android device were explained. Objects’ visualization interface representing different view types such as Buttons, ImageView, TextView or ViewGroups were described in detail for better comprehension [

38]. Unstructured interviews were carried out to access locals’ inner attitudes toward smartphones’ digital experiences: 103 people rated (<2 very weak, 3–4 weak, 5–6 moderate, 7–8 strong, 9–10 very strong) their Geomedia competence and Geomedia access. Understanding smartphone functions was a challenge for many, but most of the villagers previously used communication apps before. They considered smartphone applications necessary abstract tools with which they have to grow accustomed to. In order to obtain the innovation diffusion criterion, the Facebook geotagged posts for each rural village were identified and assessed. The georeferenced illustrations’ validation was performed using mobile data collection with the help of location-based smartphone apps. Analysis of 425 georeferenced Google illustrations and 266 geo-tagged Facebook posts contributed to the rural Geosystems’ effectiveness assessment (

Table 4).

The Romanian rural Geosystems’ effectiveness was automatically calculated (

Table 4) and validated using the Arrow theorem. Both methods generated the same order of ranking: Cund, Raven’s Nest, Viscri, Băița and Băgaciu.

3. Results

Analyzing the destination images of non-visitors, Cherifi et al. [

39] found that the majority of people create naïve images about a geographical place, using collective stereotypical images, based on a location’s common and unique functional attributes. There is a strong positive correlation between the analyzed villages’ unique attributes score and their georeferenced illustration values. The only exception is represented by Raven’s Nest (0.154/70) as a result of its recent establishment. Milne et al. [

40], emphasized the media’s essential role in the fabrication of a tourist site. The important innovation diffusion scores registered in Viscri, Cund, Băița and Raven’s Nest demonstrate their integration capacity in transformative international networks. The village of Băgaciu’s lower value (0.212 rw) reveals a significant decline in its online media presence. The Romanian villages’ common functional attributes were identified and compared. The results show that climate characteristics are similar, recommending rural villages’ visits between April–October. Natural landscape features are unchanging in form and character. Remote areas of wooden hills and difficult-to-reach valleys due to poor road networks represent other common functional attributes. Alternatively, we found out that Romanian rural destinations’ image components can differ from common characteristics to unique features. Rural Romania’s cultural identity is reflected in household construction styles and in the Romanian Orthodox, Hungarian Reformat or Saxon Evangelist churches, demonstrating the presence of sufficient unique attributes for future tourist sites’ inception.

Initiatives for tourism development were registered after 1989, when locals from rural Romanian villages tried to offer accommodation for Romanian or foreign tourists, but their attempts were unsuccessful. Most rural households have a guestroom for special occasions. The new democratic political system provides increased access to Geomedia, encouraging small tourism business development. The highest scores were registered in Raven’s Nest (0.198) and Cund (0.196). Our research results showed that most Romanians are proud of their cultural inheritance and natural beautiful landscapes; but how can anyone promote traditional culinary products such as sarmale (Romanian cabbage rolls), mamaliga (polenta), mititei (grilled ground meat rolls), tochitura (Romanian pan-fried pork), gulas (goulash), tuica-palinca-horinca (Romanian spirit made of plums) without Geomedia competences? Where else in Europe can one see peasants working arable land with horses and cows? Chickens, pigs or sheep are spread in most of the rural households situated beyond the forest and up in the Carpathian Mountains. With a proper increase in Geomedia competencies, the rural Geosystems’ functionality might gain relevance for tourism and reliability.

Tanahasi [

41] explained the pertinence of a strategy for the enhancement of communal viability. The envisaged strategy has to promote community members’ interest and initiatives through engaging entrepreneurial activities related to sustainable tourism development. Increased economic opportunities within the local community will encourage villagers to stay in their village and participate in the evolution of the rural area.

The freely available Geomedia tools can define the villages’ virtual representation as a functional Geosystem. The rural destination’s unique attributes are expressed through photos of households that are providing accommodation, photos of cultural locations such as old churches, traditional houses or museums, photos of old grown trees or wildlife from the nearby virgin forest, and photos from different cultural events. Ritchie and Goeldner [

42] pointed out that culture represents a long-lasting feature of a destination, untouchable in the tourism development process. The image of rural villages depends on the host community’s creativity in designing and providing appropriate local experiences for potential tourists. In this regard, the village of Cund represents the best example, being the most efficient Geosystem according to analysis (93 weighted sums). Storey [

43] considered the popular culture concept, a culture well-liked by many people and always adapting to the local context.

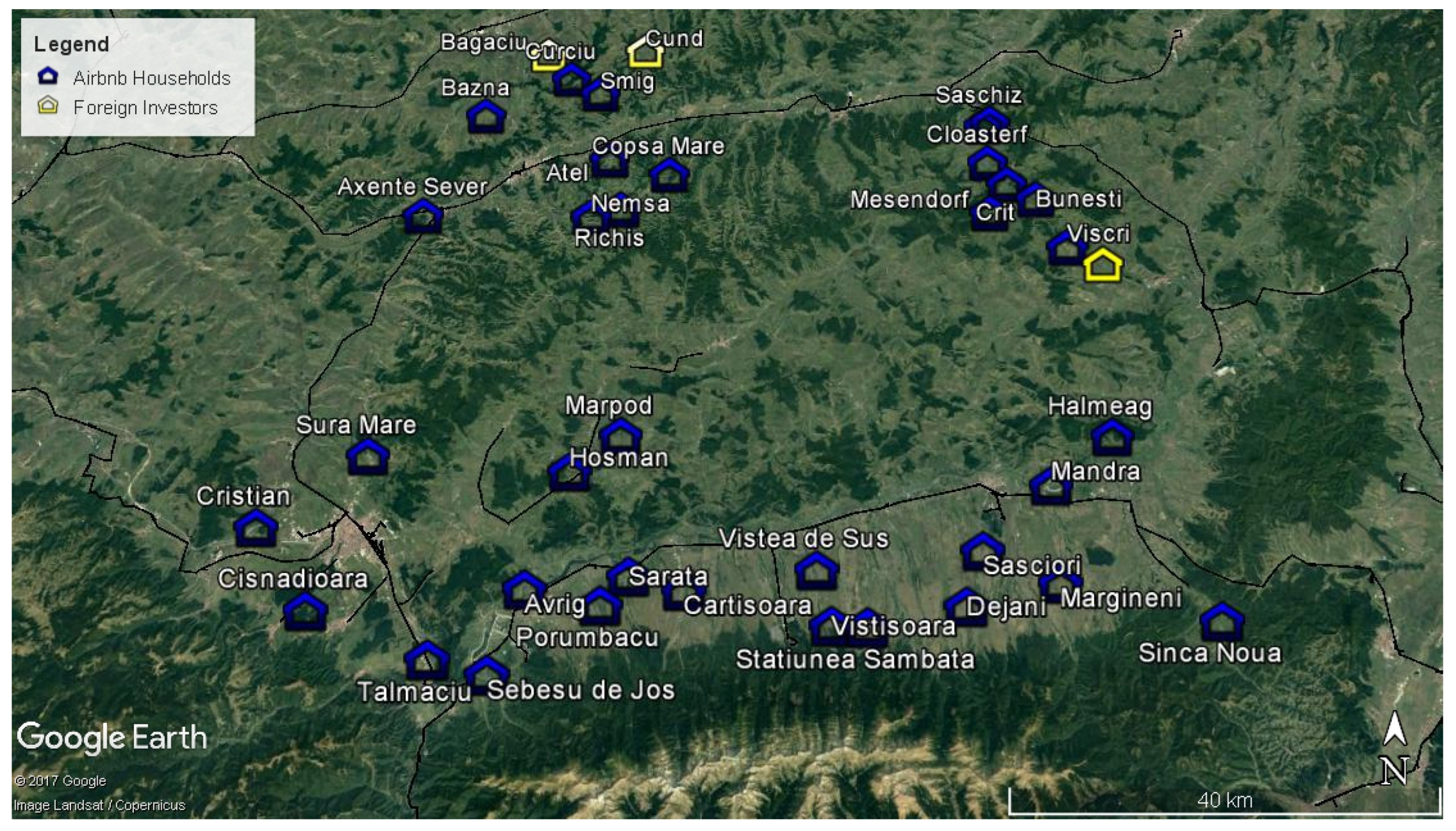

Adjusting geospatial information to villagers’ specific needs is very important in terms of correlation between the rural destination’s image and a tourism geolocation, presented in tailored maps made available online and offline with free downloadable applications for smartphones. Modern accommodation sites such as Hostelbooking, Hostelworld, Boooking and Airbnb have friendly interfaces that can be easily maneuvered by rural inhabitants who are eager to improve their livelihood: A number of 37 households were identified as active hosts. The Airbnb blooming in the rural areas proved the existence of villages’ strong unique attributes based on their exquisite landscapes, ancient traditions and well-preserved cultural heritage (

Figure 1).

This study finds evidence for the argument that education stimulates creativity. The Mihai Eminescu Trust (MET) organization’s activity in Viscri village, since 1999, included restoring 105 buildings restored according to the Saxon traditional style, educating the local workforce and using locally produced materials. Villagers were trained in the traditional fabrication techniques in order to preserve their Geosystem’s unique attributes [

37]. MET is an NGO based in England, patroned by Prince Charles, interested in rural Transylvanian diversity and specific culture. MET’s constant lobbying significantly contributed to Viscri’s international innovation diffusion (0.224 rw). MET funded households’ facades restoration, but the reconstruction of the houses’ interiors was completed individually by their inhabitants. MET also started tourism promotion using their international network connections, encouraging locals to get involved for additional income. As a result, Viscri has a georeferenced illustration score of 0.220 rw, which represents the highest value among the analyzed villages.

Iorio and Corsale [

44] observed that ‘model guesthouses’ were opened by MET in order to motivate local initiatives in Transylvanian rural communities where rural tourism had never been practiced. It also entails the identification of unique attributes and the characterization of elements for multiscale modeling. Using information from Viscri, Cund, Bagaciu, Baita and Raven’s Nest, the Romanian rural Geosystems’ structure–attributes correlation was possible. The Geomedia technique can be applied in any rural location if the villagers have smartphones with a camera, integrated GPS and internet connection possibilities.

Croitoru et al. [

45] emphasized the role of the general public as the main donor of big data, due to smartphone application advancements. They generate various geolocated media through web services. This study argues that social media feeds with considerable geospatial information represent Geomedia. The tourists’ need for different accommodation infrastructure has shifted from standard hotels, which offer similar conditions on every continent, to particular private households, with their unique personality. In this regard, Garau [

46] suggested the development of online platforms that would be administrated and updated by the local community. Geomedia tools, such as smartphone applications for geotagged photos’ placement on Google Maps, Maverick’s directions tracking system, Google Earth’s Explore visualization or Facebook’s sharing opportunities, were prerequisites for the creation of the virtual local Geosystems in Bagaciu, Cund, Viscri, Baita and Raven’s Nest. Their functional interconnected components proved the efficiency of human behavior in shaping the Romanian rural world. Nowadays, tourists in Viscri, Cund and Raven’s Nest cherish an experience that would take them deep into another culture.

This study predicts that modern smartphone applications will challenge Romanian people to realize rural areas’ potential and take steps towards transforming these areas with the aid of smart apps into proactive and creative tourist destinations. Cund, Viscri and Raven’s Nest have unique cultural attributes that are transforming them into exquisite rural destinations. While imagining Facebook applications as a window that allows us to watch other humans’ experiences, Airbnb might represent the travel gate into their real life. The geographical extrapolation of functional Geosystems’ visual imagery is demonstrated by Airbnb’s web platform structure, where the locations’ geospatial coordinates are correlated to the environmental component’s properties and functionalities. Photographic elements’ characterization illustrates the experiences offered by the inhabitants. The validation process of the virtual Geosystem includes visitor’s reviews and ratings. In this regard, a study of the Baita village revealed quite a significant potential, harnessed through the Airbnb smart app (

Figure 2).

For more than two years, after a traditional household was rebuilt and presented on Airbnb’s virtual platform, international tourists blended in in the Romanian village with a 0.225 rw unique attributes score. Relph [

47] argued that geographical location representation qualities are directly influencing people’s imagined experience of that place. Although BCH is the only accommodation offered in Baita village, this study estimates that other households will follow soon due to the excellent innovation diffusion value of 0.250 rw. Many young people are returning to the rural areas, increasing the Geomedia competence rate (0.150 rw). They bring with them new ideas and possibilities given by the evolution of technology, and by smartphone apps used for images geotagging and Airbnb account creation. They are also investing in their houses heating system, to provide hot water for showers and better restroom conditions.

Smartphone geo-applications are guiding tourists when they make their own way through the forest, and if uploaded, the track they have taken can be used by others and improved with time. Cund (Reussdorf), Bagaciu (Kleinferken) and Viscri’s (Deutsch Weisskirch) Saxon heritage Geosystems proved to attract international tourists. Currently, it is the old and traditional Romanian rural houses that are appealing to the visitors. This is vividly portrayed by the owners of the Raven’s Nest and Valea Verde in Cund, who would use the Facebook smartphone application to say that: ‘at the Valea Verde we have set out to create a true rural retreat that provides our guests with all basic comfort whilst preserving the simple, authentic charm of a farmhouse in the middle of a breathtaking natural setting’ [

48,

49]. Although the organic way of life tends to make many Romanian peasants use the backyard commode more than the indoors, it should not be overused. Both have their place in Romania’s image. On the other hand, we observed that the lack of bathroom conditions might influence the rural household’s service requests. Amblee [

2] determined cleanliness as an increasing security factor regarding geolocation, arguing that accommodations from unappealing areas should concentrate on the special maintenance of freshness in order to compensate.

The Valea Verde Resort in Cund represents one the best examples of an effective Geosystem (93 ws) with excellent unique attributes and innovation diffusion scores. It uses the available natural and anthropic resources in order to become an environmentally friendly and attractive tourist destination. The German investor Jonas Schafer can be seen as the main contributor and channel of energy flow inputs in Cund’s Geosystem, as he has developed a network of entrepreneurs and guides that bring tourists here, promote the location further online and add value by sharing ideas and personal experiences. On the contrary, at Bagaciu, the system was a closed circuit, as the tourism activity was directed strictly by the Danish investors who did not involve nor educate the locals. Low values of Geomedia access (0.152 rw) and competence (0.121 rw) were registered in Bagaciu. Locals did not take an active part in the business, which turned out to be the reason why the tourism activity ceased at Bagaciu after the Danish investors left.

The initial lack of mobile phone signals in Cund did not discourage tourism activity; on the contrary, it contributed to the increase in experienced tourists. Offline smartphone applications’ functions and Wi-Fi spots are available if needed. It is like traveling back in time, far away from the rush that characterizes modern civilization, into the Romanian communities that offer the perfect escape experience in an exquisite environment.

The study finds that the best rural community redefinition was made possible by the German developer named Jonas Schaffer, whose ideas were perfectly applied in the village of Cund with the full support of the residents (

Figure 3). Torben Schreiber from Denmark applied his ideas in Bagaciu village, transforming it into a tourist destination for Danish people. Both are situated in the middle of Romania, not far from one another [

49,

50].

Bagaciu and Cund villages have had something in common, besides responsive web design for a mobile friendly location website and the fact that their investments are both located on left side tributaries of the Tarnava Mica River. The locations have similar geographical features as the hilly region, the small villages being inhabited by Romanians, Hungarians and Gypsies that came after the Saxons left Romania for Germany. The most important element of the foreign investors’ success in Bagaciu and Cund alike was represented by the Saxon families that remained in the community and took care of the administrative aspects of the rural tourism business. The development of sustainable rural tourism started in Bagaciu and Cund on similar premises, with the locations being choose by the Danish and German investors, who were looking for remote traditional rural communities able to accommodate teenagers in re-education programs. They managed to rearrange old houses in a traditional way, taking into account the local architectural style and using some of the skilled inhabitants as workers.

Tourists started to come in Bagaciu from Denmark, with a charter flight to the Transylvania Airport of Targu Mures, from April until October. Families with children, elder people and members of Danish pension clubs were happy to spend a week in such a natural and relaxing environment. Smartphone photos and videos rapidly spread on Danish social networks.

Three valleys upstream from Tarnava Mica to the East, the Cund village has received Germans and other nationalities, including Romanian tourists. They were offering a similar package to a broader pallet of clients instead of the close circuit reserved only for Danish tourists like Bagaciu did. As a result, now the Valea Verde Retreat Facebook page had the attention (like) of 81,553 people until December 2021. That shows an increasing influence on rural Romanian tourism, aided by people who have been satisfied with the services Jonas Schafer and his team provide and who sought to inform others and promote the place by tagging it in georeferenced photos and positive reviews [

8,

49]. A rather inconvenient location by accessibility terms, Cund is welcoming both Romanian and international tourists. Via smartphone apps, their captured images are showing Valea Verde Resort’s beauty to the entire world [

50,

51].

Local communities from Bagaciu and Cund would not have had to start and manage a successful, sustainable tourism development project without foreign investors’ initiative. The community’s livelihood was enhanced because of tourism, a complementary activity to traditional activities, assuring an extra income for the families involved. The most authentic activities of the rural residents stand out in Viscri and Cund. The Lascu family from Viscri traditionally produces bricks and tiles using local clay. The Gabor family from Viscri specializes in blacksmithing and produces iron locks, hinges and chandeliers. More than one hundred women from Viscri weave wool socks to sell locally or send to Germany in Naumburg. For production, the Cheese Factory run by the Varga family only uses the milk from its own farm and processes 350 L per day, while the cheese matures for about two months. The Varga family from Cund do not want to sell for export, given that long-distance transport also comes with additional carbon dioxide emissions. Tourism is considered sustainable when it is focused on the local community members and on the local natural resources that can upgrade peoples’ life standards [

44].

Formalizing the process for promoting rural tourist sites would require several steps (

Figure 4). First, the living space needs to be imputed. Second, the supervisory department should play a mediation role in optimizing the service of tourism. Third, the improvement of social networks and tourist-oriented applications is the important factor driving the tourists’ need. Finally, when the coordination relationship among all factors is established, the pension will promote accordingly. This formalization allows for the understanding of this activity by all persons who can bring added value for the promotion of accommodation units within more isolated communities [

52].

4. Discussion

This study’s findings on the rural Geosystem’s future in the smartphone world revealed that the inception of Romanian tourist sites was and is possible with the help of new technologies such as smartphone applications including Airbnb, Booking, Facebook and WhatsApp, which are regularly used for information and communication purposes, or Google Maps, Sygic and Waze, for orientation/directions, because of their free availability and convenience [

1,

8,

35]. Taking into account that the internet is widespread in Romania, our collected data proved the existence of the smartphone phenomena in all analyzed locations and estimates that smartphone applications’ future use will gradually increase. The significant growth of Facebook, Google and WhatsApp users was observed, but only a slightly lower involvement for Airbnb [

1,

8,

20,

35]. Therefore, the modern Geomedia approach with a variety of functional smartphone applications is slowly envisaged by rural society. On the contrary, the European Union’s development programs in the rural areas are using all the Geomedia advantages. Koutsouris [

53] underlined the importance of LEADER projects in the transformation process from a ‘less favored area’ into a major tourism destination. The rural space’s visual imagery combines geospatial Google presence and search engine detection with social media apps such as Facebook, WhatsApp or Airbnb, shaping the structure–elements attribute correlations for the leisure activities’ development and tourist sites’ creation [

48,

54].

The significant development of Airbnb, and more recently Google, was based on evolved forms of geographical information systems where the individual host’s creativity enhancement was meant to influence peoples’ imagined experience of the place. The collective stereotypical images were used as common functional attributes. The rating and reviewer systems were identified as the best validation solutions for the unique experiences that anyone can offer as an individual host or part of a community-based tourism project. Geomedia methodology integrates the smartphone applications such as WhatsApp for communication, Facebook for sharing, Google Maps for directions, and Airbnb and Google Earth for the Geosystem’s virtual illustration. It is important to notice that Geomedia techniques can be applied in any remote village around the world, not only in Romania, but the inception of the tourist sites is dependent on the internet’s availability for innovation diffusion, georeferenced illustration and access to Geomedia.

These research results showed that Viscri emphasized international marketing efficiency, with the exquisite fortified Saxon church and beautiful restored house photographs internationally spread by the visitors and foreign investors. For example, the Viscri Geosystem’s unique attribute qualities were shared to the world by the Mihai Eminescu Trust (MET) organization, increasing its integration in transformative international networks. They were responsible for the innovation diffusion and the georeferenced illustration criterions’ high scores. MET experiments in Viscri proposed that local society’s education can be the main factor in rural tourism development [

31,

37]. They invested time, money and energy in the local Geosystem. The villagers learned how to manufacture lumber, bricks and roof tiles in the traditional way. MET knowledge represented the information input into the Viscri Geosystem. They taught inhabitants how to use their natural resources such as clay and timber and transform them into valuable assets. Visiting Viscri means going back in time and seeing something that is less and less available to the public at large, mainly, a functioning yet uniquely preserved village. The Geosystem is in a dynamic natural equilibrium, with a balanced number of tourist inputs, instructed villagers and interconnected functional components.

This analysis also finds that compared to Viscri, the village of Cund incorporates the new rustic shapes into its past, creating something new and rustic yet attractive to the public. Some would say the village of Cund is an ordinary Romanian village, but it is the place picked by Jonas Schafer to rebuild the local community in a tourism-oriented way. The German investor constitutes the energy infused in the Cund Geosystem, identifying the valuable assets (unique attributes) and linking the functional components to increase the innovation diffusion. Merging the old traditional style of the houses with new technology, the tourist that comes here is sure to be impressed by the modern conditions (hot water, in-house restrooms) included in the rustic accommodations. Cund’s Geosystem’s behavioral computation and structure–elements attribute correlations were settled. Jonas gives every tourist that walks his threshold a wonderful experience, a warm welcome and a taste of Romanian hospitability. Due to the Geomedia methodology, the extrapolation of Cund’s functional visual imagery structure is possible in any other rural location.

This article confirms that going off the beaten path is a challenge, but it is usually made easier by the few tourists that have been there before and decided to take a picture with their smartphone and post it online, to let the world know where they are, but also indirectly drawing attention to a lesser-known place [

48]. Remotely located on the main Romania rivers’ upper valleys, each of the chosen study sites presents difficult access possibilities due to bumpy gravel roads. For example, Cund and Bagaciu are spread on two parallel Tarnava Mica river tributaries, Viscri on Gorgan and Baita on Baia creeks.

This article proves that Bagaciu’s Geosystem was a functional tourist site as long as the foreign investor provided

material inputs, in the form of Danish tourists, that came for years, every week from April until October. This analysis reveals that Schreiber did not invest in local inhabitant’s education as MET or Jonas did in Viscri and Cund, where second-home tourism was encouraged [

54]. Without

energy and

information foreign inputs, Bagaciu’s Geosystem collapsed when the tourists from Denmark stopped coming. Based on their research, Carson and Carson [

55] state that the immigrants might innovate rural tourism development. However, apart from international knowledge contribution, Iorio and Corsale [

51] argued that the Romanian government’s policies should be more supportive of rural tourism development initiatives. Many individuals want to learn how to use the new technological advances to transform their homes into guesthouses and attract tourists in their villages.

This study also finds that Baita village’s Geosystem is characterized by the same common environmental components as Viscri, Cund or Bagaciu, possessing old houses and well-preserved traditional customs as unique functional features. The information input is unidirectional, without energy for other villagers’ education. As a result, the Geomedia competence (0.150/60) is low, although the access to Geomedia has a slightly higher score (0.175/70). Tourists are coming for the Cozy House only, which has a balanced Geosystem, operational at its scale with the highest score for innovation diffusion (0.250/100). Using Geomedia methodology in a collaborative way, the local inhabitants will enable the performance extension and geographical extrapolation of the Cozy House’s Geosystem functionality, learning to become more resilient and adaptive to change, slowly transforming their village into a tourist site.

5. Conclusions

Firstly, this analysis revealed that remote communities around the world might represent the new tourism destinations with the help of smartphone applications. Secondly, this article examined the Romanian locations that are off the beaten track, which apart from the crowded resorts, started to offer a unique insight into the local lifestyle, culture and traditional customs. Thirdly, this study confirmed that adapted to the minimal modern tourist needs, even remote locations such as Raven’s Nest or Băița can provide a special vacation experience for anyone looking for something different.

This analysis provides evidence that in the rural Romanian communities, there is a tourism expertise deficiency and a considerable need for local tourism’s potential valorization. The most important constraint of smartphone-app-based tourism development in Romania rural villages is the fabrication of tourism awareness amongst rural localities, between the local inhabitants.

The Romanian rural environment is defined by a paradox. Its strength and the basis of its appeal, namely it being off the habitual tourist beaten track and a world which seems to function unaltered by modern times, also represents its weakness, as this world is also off the usual travel agency’s agenda. On the other hand, the unique geographical conditions, with difficult access possibilities due to bumpy gravel roads, determined some foreigners to take the chance and invest in a form of rural tourism that seems to be successful.

Romanian rural villages need a digital transformation strategy for their communal viability enhancement. The international interest in Romania-specific rural uniqueness has to develop further as a smart cross-cultural experience. Therefore, the rural Geosystem’s transformation in tourist sites requires the allocation of wide options for individuals to create and organize their own active encounter engagement. A single rural household’s action cannot fulfil this goal, but a matrix of collaborating inhabitants and villages that are involved together in tourism development can.

This study is not without limitations that should not be neglected, but also paves the potential road for future research. On the one hand, future researchers can explore the residents’ or tourists’ perceptions of the impact of rural geosystems in tourist sites, which is conducive to optimize the informatization of Romania. Future research might focus on the implementation of our research methodology regionally in Maramures, Moldova, Oltenia, Banat and Dobrogea. The identification of the functional rural Geosystems around the world represents a challenge for today’s researchers. On the other hand, similar studies should be conducted in other countries around Europe, Asia, Africa and Latin America to further improve the universality of this results.