Research on Urban Community Elderly Care Facility Based on Quality of Life by SEM: Cases Study of Three Types of Communities in Shenzhen, China

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Quality of Life (QOL)

2.1.1. Concept and Theory of QOL

2.1.2. Influencing Factors of QOL

2.1.3. Measurement Methods of QOL

2.2. Community Elderly Care Facilities (CECFs)

2.2.1. Functional Setting

2.2.2. Planning and Layout

2.2.3. Operation and Management

2.3. Application of Structural Equation Modeling to CECFs

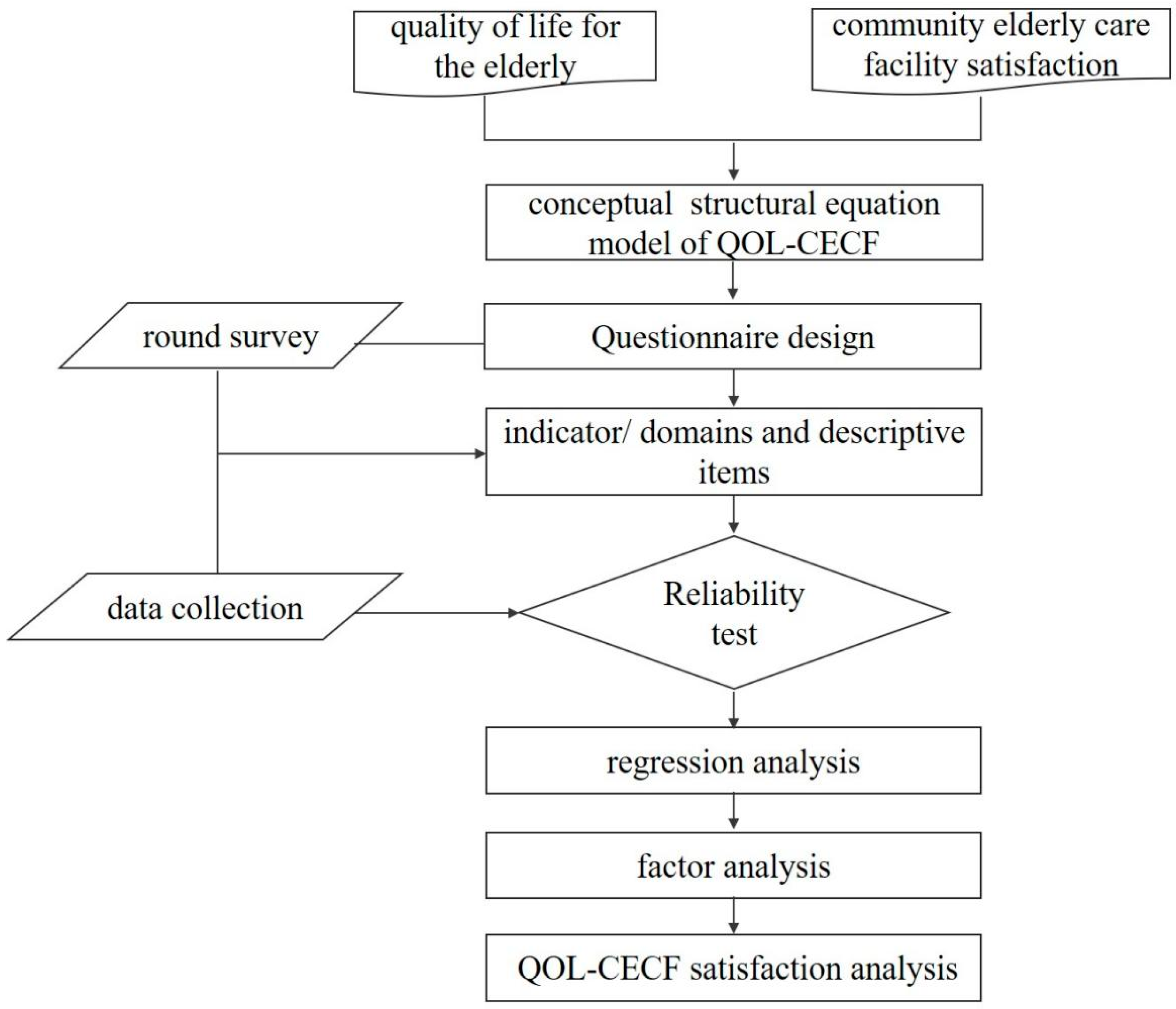

3. Methodology

3.1. Framework Creation

3.2. Research Area Description

3.2.1. Community Types

3.2.2. Research Area

3.3. SEM for QOL–CECF

3.3.1. Research Hypothesis of SEM

3.3.2. Questionnaires and Data Collection

General Information of Respondents

Assessment of QOL

CECF Satisfaction Evaluation

3.3.3. Testing and Fitting of SEM

3.3.4. API Analysis between QOL and CECF in Three Types of Community

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Results of Path Analysis of SEM

4.2. Causes of Low QOL in CECF

4.2.1. Causes of Low QOL in CECFs of Urbanized Village Communities

4.2.2. Causes of Low QOL in CECFs of Affordable Housing Communities

4.2.3. Causes of Low QOL in CECFs of Commercial Housing Communities

5. Conclusions and Limitation

5.1. Policy Recommendations

5.1.1. Strategies for CECF Construction in Urbanized Village Communities

5.1.2. Strategies for CECF Construction in Affordable Housing Communities

- (1)

- This study suggests that life care and social activity functions should be combined to solve the small-scale issue of CECFs. At the same time, the CECFs should pay attention to static and dynamic partitions and set up a separate room for life care functions to ensure the quiet use needs of the elderly.

- (2)

- The study proposes three recommendations to solve the issue of low satisfaction with the medical care functional setting. First, CECFs should cooperate with health centers and tertiary hospitals around the community to obtain stable medical service support. Secondly, CECFs should be integrated with community health centers as much as possible. Thirdly, the number and scale of medical care function rooms of CECFs should meet the design standards. CECFs should be equipped with physical therapy instruments, massage chairs, and other equipment.

5.1.3. Strategy for the CECF Construction in Commercial Housing Communities

- (1)

- The study suggests that increasing the number of life care and social activity CECFs using public areas can solve the lack of life care and social activity function rooms in commercial housing communities. It is recommended that CECFs, such as elderly activity rooms or canteens, should be combined with other public rooms in the community, such as property management rooms and community service stations. In addition, the outdoor space of CECFs in commercial housing communities can be flexibly increased. Shenzhen is a subtropical city, and most residential buildings are elevated on the ground floor to form a semi-outdoor space that can shelter from the wind and rain. Elderly activity rooms and canteens can be set up in these semi-outdoor areas.

- (2)

- CECFs should import specialized elderly care institutions to improve service quality. The elderly in commercial housing communities have high demands for the service quality of CECFs and high service affordability. The government should encourage professional elderly care institutions to operate CECFs and provide specialized and personalized assistance to the elderly. In addition, CECFs should strengthen staff training and standardize service quality.

5.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tu, Y.Y.; Lai, Y.L.; Shin, S.C.; Chang, H.J.; Li, L. Factors associated with depressive mood in the elderly residing at the Long-Term care facilities. Int. J. Gerontol. 2012, 6, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mccabe, M.P.; Mellor, D.; Davison, T.E.; Karantzas, G.; Treuer, K.V.; O’Connor, D.W. A study protocol to investigate the management of depression and challenging behaviors associated with dementia in aged care settings. BMC Geriatr. 2013, 13, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sohn, M.; O’Campo, P.; Muntaner, C.; Chung, H.; Choi, M. Has the long-term care insurance resolved disparities in mortality for older Koreans? examination of service type and income level. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 247, 112812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karakaya, M.G.; Bilgin, S.; Ekici, G.; Köse, N.; Otman, A.S. Functional mobility, depressive symptoms, level of independence, and quality of life of the elderly living at home and in the nursing home. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2009, 10, 662–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gilleard, C.; Hyde, M.; Higgs, P. The impact of age, place, aging in place, and attachment to place on the well-being of the over 50s in england. Res. Aging Int. Bimon. J. 2007, 29, 590–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.J. Understanding aging in place: Home and community features, perceived age-friendliness of community, and intention toward aging in place. Gerontologist 2022, 62, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Pickard, J.G. Aging in place in naturally occurring retirement communities: Transforming aging through supportive service programs. J. Hous. Elder. 2010, 22, 304–321. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.H.; Zhou, G.T.; Shin, J.H.; Kang, Y.H. Locating community-based comprehensive service facilities for older adults using the GIS-NEMA method in Harbin, China. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2021, 147, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Font, J.; Courbage, C.; Swartz, K. Financing Long-Term Care: Ex Ante, Ex Post or Both? Health Econ. 2015, 24, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Friedman, C.; Caldwell, J.; Kennedy, A.R.; Rizzolo, M. Aging in Place: A national analysis of home and community based medicaid services for older adults. J. Disabil. Policy Stud. 2019, 29, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentieri, G.; Guida, C.; Masoumi, H.E. Multimodal accessibility to primary health services for the elderly: A case study of naples, Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, L.; Huang, Y.Q.; Zhang, W.H. Residential segregation and perceptions of social integration in Shanghai, China. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 1484–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.F.; Dijst, M.; Geertman, S. Residential segregation and well-being inequality between local and migrant elderly in Shanghai. Habitat Int. 2014, 42, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yearwood, E.L.; Siantz, M.D. Global issues in mental health across the life span: Challenges and nursing opportunities. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2010, 45, 501–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Wu, Y.; Xu, X.; Chen, Y. Spatial disparities and correlated variables of community care facility accessibility in rural areas of China. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Qiao, C.; Liu, S.; Wang, C.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.; Huang, P. Assessment of spatial accessibility to residential care facilities in 2020 in Guangzhou by small-scale residential community data. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nguyen, L.T.; Nantharath, P.; Kang, E. The sustainable care model for an ageing population in Vietnam: Evidence from a systematic review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Z.; Lin, L.; Yang, Y. Study on the health status and health service utilization for the rural elderly in the metropolitan suburb during the urbanization process: A case for Mingxing Village, Guangzhou. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.T.; Chen, P.E.; Liu, C.Y.; Chien, W.H.; Tung, T.H. The association between quality of life and nursing home facility for the elderly population: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Gerontol. 2021, 15, 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Grasso, M.; Canova, L. An Assessment of the Quality of Life in the European Union Based on the Social Indicators Approach; University Library of Munich: München, Germany, 2007; Volume 87, pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Herrman, H.; Metelko, Z.; Szabo, S.; Rajkumar, S. Study protocol for the world-health-organization project to develop a quality-of-life assessmnet instrument (WHOQOL). Qual. Life Res. 1993, 2, 153–159. [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrm, B. Quality of life: A model for evaluating health for all conceptual considerations and policy implications. Soz.-Und Präaventivmedizin SPM 1992, 37, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Post, M.W.; De, W.L.P.; Schrijvers, A.J.P. Quality of life and the ICIDH: Towards an integrated conceptual model for rehabilitation outcomes research. Clin. Rehabil. 1999, 13, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westaway, M.S.; Olorunju, A.S.A.; Rai, L.C.J. Which personal quality of life domains affect the happiness of older South Africans? Qual. Life 2007, 16, 1425–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senasu, K.; Singhapakdi, A. Quality-of-Life determinants of happiness in Thailand: The moderating roles of mental and moral capacities. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2018, 13, 59–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasution, A.D.; Zahrah, W. Community perception on public open space and quality of life in Medan, Indonesia. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 153, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Geffen, L.N.; Kelly, G.; Morris, J.N.; Howard, E.P. Peer-to-peer support model to improve quality of life among highly vulnerable, low-income older adults in Cape Town, South Africa. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banjare, P.; Pradhan, J. Socio-Economic inequalities in the prevalence of multi-morbidity among the rural elderly in Bargarh District of Odisha (India). PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e97832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprangers, M.A.G.; Schwartz, C.E. Integrating response shift into health-related quality of life research: A theoretical model. Soc. Sci. Med. 1999, 48, 1507–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadi-Lari, M.; Tamburini, M.; Gray, D. Patients’ needs, satisfaction, and health related quality of life: Towards a comprehensive model. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2004, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hyde, M.; Wiggins, R.D.; Higgs, P.; Blane, D.B. A measure of quality of life in early old age: The theory, development and properties of a needs satisfaction model (CASP-19). Aging Ment. Health 2003, 7, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davern, M.; Winterton, R.; Brasher, K.; Woolcock, G. How can the lived environment support healthy ageing? A spatial indicators framework for the assessment of Age-Friendly communities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 7685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosch-Meda, J. Is the role of urban planning in promoting active ageing fully understood? A comparative review of international initiatives to develop Age-Friendly urban environments. ACE-Archit. City Environ. 2021, 16, 10337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zikmund, V. Health, well-being, and the quality of life: Some psychosomatic reflections. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2003, 24, 401–404. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kiritz, S.; Moos, R.H. Physiological effects of social environments. Psychol. Soc. Situat. 1981, 36, 136–158. [Google Scholar]

- Fagerstrm, C.; Borglin, G. Mobility, functional ability and health-related quality of life among people of 60 years or older aging clinical and experimental research. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2010, 22, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalenques, I.; Auclair, C.; Rondepierre, F.; Gerbaud, L.; Tourtauchaux, R. Health-related quality of life evaluation of elderly aged 65 years and over living at home. Rev. d’Épidémiologie St. Publique 2015, 63, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Man, G.K.; Lee, H.B.; Lim, K.M.; Lee, H.K.; Kim, T.S. Differences in quality of Life, subjective health status, and medical expenses of obese elderly women according to their physical activities. J. Korean Soc. Study Phys. Educ. 2021, 25, 309–323. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.W.; Zeng, L.R. A quality of life oriented study of time allocation and travel for older adults. Urban Transp. 2019, 17, 64–69. [Google Scholar]

- Goulias, K.G.; Ravulaparthy, S.; Polydoropoulou, A.; Yoon, S.Y. An exploratory analysis on the Time-or-Day dynamics or episodic hedonic value or activities and travel. In Proceedings of the Transportation Research Board Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 13–17 January 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Veerle, V.H.; Sarah, M.N.; Megan, T.; Timperio, A.; Dyck, D.V.; Bourdeaudhuji, I.D.; Salmon, J. Social and physical environmental correlates of adults’ weekend sitting time and moderating effects of retirement status and physical health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 9790–9810. [Google Scholar]

- Mahapatra, G.D. Neighborhood Planning: Approach in Improving Livability and Quality of the Life in the Cities; Springer: Singapore, 2017; Volume 12, pp. 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, L.; Silva, A.; Rech, C.R.; Fermino, R. Physical activity counseling among adults in primary health care centers in Brazil. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 10, 5079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, M.E.; Kenyon, C. A measure of positive health-related quality of life: The Satisfaction with Illness Scale. Psychol. Rep. 1992, 71, 1137–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S.H.; Pan, Y.; Xu, Y.B.; Yeung, K.C. Life satisfaction of 511 elderly Chinese stroke survivors: Moderating roles of social functioning and depression in a quality of life model. Clin. Rehabil. 2020, 35, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steuer, J.; Bank, L.; Olsen, E.J.; Jarvik, L.F. Depression, physical health and somatic complaints in the elderly: A study of the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale. J. Gerontol. 1980, 35, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eijk, L.; Kempen, G.I.J.M.; Sonderen, F.L.P.V. A short scale for measuring social support in the elderly: The SSL12-I. Tijdschr. Voor Gerontol. Geriatr. 1994, 25, 192–196. [Google Scholar]

- WHOQOL-BREF: Introduction, Administration, Scoring and Generic Version of the Assessment. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/63529/WHOQOL-BREF.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Curtis, M.P.; Kiyak, A.; Hedrick, S. Resident and facility characteristics of adult family home, adult residential care and assisted living settings in Washington State. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2000, 34, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guihan, M.D.T.M.; Mambourg, F. What do potential residents need to know about assisted living facility type? The trade-off between autonomy and help with more complex needs. J. Hous. Elder. 2011, 25, 109–124. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, K.L.; Castillo, R.J. The U.S. Long Term Care System: Development and expansion of naturally occurring retirement communities as an innovative model for aging in place. Ageing Int. 2012, 37, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, M.; Hattori, K.; Nakashima, T.; Sawamura, K. Health care and personal care needs among residents in nursing homes, group homes, and congregate housing in Japan: Why does transition occur, and where can the frail elderly establish a permanent residence? J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2014, 15, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatsuya, N. Quantitative properties of the macro supply and demand structure for care facilities for elderly in Japan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1489. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, K.B.; Lee, C.E. Integration of primary care with hospital services for sustainable universal health coverage in Singapore. Health Syst. Reform. 2019, 5, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Feng, Q.S.; Straughan, P.T. What does successful aging mean? lay perception of successful aging among elderly Singaporeans. J. Gerontol. 2017, 72, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Ho, C.; Wong, L.; Cheah, J. Singapore programme for integrated care for the elderly(spice): A pilot project to enable frail elderly to be cared for in the community. Gerontologist 2013, 53, 443. [Google Scholar]

- Hannah, W.M.A. On the relationship between the size of residential institutions and the well-being of residents. Gerontologist 1981, 21, 247–250. [Google Scholar]

- Sikorska, E. Organizational determinants of resident satisfaction with assisted living. Gerontologist 1999, 39, 450–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shippee, T.P.; Henning-Smith, C.; Gaugler, J.E.; Held, R.; Kane, R.L. Family satisfaction with nursing home care. Res. Aging 2017, 39, 418–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yang, Y.T.; Iqbal, U.; Ko, H.L.; Wu, C.R.; Chiu, H.T.; Lin, Y.C.; Lin, W.; Hsu, Y.E. The relationship between accessibility of healthcare facilities and medical care utilization among the middle-aged and elderly population in Taiwan. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2015, 27, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Grant, T.L.; Edwards, N.; Sveistrup, H.; Andrew, C.; Egan, M. Neighborhood walkability: Older people’s perspectives from four neighborhoods in Ottawa, Canada. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2010, 18, 293–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Asthana, S.; Gibson, A.; Moon, G.; Dicker, J.; Brigham, P. The pursuit of equity in NHS resource allocation: Should morbidity replace utilisation as the basis for setting health care capitations? Soc. Sci. Med. 2004, 58, 539–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, N.L. Identifying the potential location of day care centers for the elderly in Tokyo: An integrated framework. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2020, 13, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.C.; Chen, C.F. LTC 2.0: The 2017 reform of home and community-based Long-Term Care in Taiwan. Health Policy 2020, 126, 722–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, Y.T. A quality function deployment-based resource allocation approach for elderly care service: Perspective of government procurement of public service. Int. Soc. Work 2021, 64, 992–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.Y.; Ku, P.Y.; Wang, Y.T.; Lin, Y.H. The effects of job satisfaction and ethical climate on service quality in elderly care: The case of Taiwan. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2014, 27, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, G.; Dubois, M.F.; Demers, L. Does regulating private long-term care facilities lead to better care? A study from Quebec, Canada. Int. J. Qual. Health 2014, 26, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beland, F.; Lemay, A. Dilemmas and values for Long-Term-Care policies. Can. J. Agng-Rev. Can. Du Vieil. 1995, 14, 263–293. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.Y.; Chou, E.Y. Stepping up, stepping out: The elderly customer long-term health-care experience. J. Serv. Marking 2022, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spearman, C. General intelligence: Objectively determined and measured. Psychology 1904, 5, 201–293. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, S. Path coefficients and path regression: Alternative or complementary concept. Biometrics 1960, 16, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elosua, P. Subjective values of quality of life dimensions in elderly people. A SEM preference model approach. Soc. Indic. Res. 2011, 104, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Zhang, S.; Kang, J. Estimation of the quality of life in housing for the elderly based on a structural equation model. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2021, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlan, A.; Ibrahim, S.; Masuri, M.G. Role of the physical environment and quality of life amongst older people in institutions: A mixed methodology approach. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2016, 234, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mahmoodi, Z.; Yazdkhasti, M.; Rostami, M.; Ghavidel, N. Factors affecting mental health and happiness in the elderly: A structural equation model by gender differences. Brain Behav. 2022, 12, e2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Li, D.Z.; Chan, A.P.C. Diverse contributions of multiple mediators to the impact of perceived neighborhood environment on the overall quality of life of community-dwelling seniors: A cross-sectional study in Nanjing, China. Habitat Int. 2020, 104, 102253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuuren, J.V.; Thomas, B.; Agarwal, G.; MacDermott, S.; Kinsman, L.; O’Meara, P.; Spelten, E. Reshaping healthcare delivery for elderly patients: The role of community paramedicine; a systematic review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Guzman, A.B.; Lagdaan, L.F.M.; Lagoy, M.L.V. The role of life-space, social activity, and depression on the subjective memory complaints of community-dwelling Filipino elderly: A structural equation model. Educ. Gerontol. 2015, 41, 348–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, L.D.S.C.B.; Souza, E.C.; Rodrigues, R.A.S.; Fett, C.A.; Piva, A.B. The effects of physical activity on anxiety, depression, and quality of life in elderly people living in the community. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2019, 41, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, P. Activity nursing and the changes in the quality of life of elderly patients: A semi-quantitative study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2010, 18, 1727–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, M.; Li, Y.; Guo, C.Y.; Yeh, C.H. Community canteen services for the rural elderly: Determining impacts on general mental health, nutritional status, satisfaction with life, and social capital. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loo, B.P.Y.; Lam, W.W.Y. Geographic accessibility around health care facilities for elderly residents in Hong Kong: A microscale walkability assessment. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2012, 39, 629–646. [Google Scholar]

- Kanoh, A.; Kizawa, Y.; Tsuneto, S.; Yokoya, S. End-of-Life care and discussions in Japanese geriatric health service facilities: A nationwide survey of managing directors’ viewpoints. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2018, 35, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Challiner, Y.; Julious, S.; Watson, R.; Philp, I. Quality of care, quality of life and the relationship between them in Long-Term Care institutions for the elderly. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 1996, 11, 883–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodore, K.; Lalta, S.; La Foucade, A.; Ewan, S.; Anton, C.; Christine, L.; Charmaine, M. Financing health care of the elderly in small societies: The case of the Caribbean. Ageing Int. 2017, 42, 324–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Goal | Dimension | Indicators |

|---|---|---|

| QOL | Physical | Pain and discomfort |

| Energy and fatigue | ||

| Sleep and rest | ||

| Mobility | ||

| Activities of daily living | ||

| Dependence on medication or treatments | ||

| Work capacity | ||

| Psychological | Positive feelings | |

| Thinking, learning, memory, and concentration | ||

| Self-esteem | ||

| Bodily image and appearance | ||

| Negative feelings | ||

| Spirituality | ||

| Social relationships | Personal relationships | |

| Social support | ||

| Sexual activity | ||

| Environment | Physical safety and security | |

| Home environment | ||

| Financial resources | ||

| Health and social care: accessibility and quality | ||

| Participation in and opportunities for recreation leisure activities | ||

| Opportunities for acquiring new information and skills | ||

| Physical environment | ||

| Transport |

| Area | Percentage of Total Population | |

|---|---|---|

| Over 60 Years Old | Over 65 Years Old | |

| City-wide | 5.36% | 3.22% |

| Luohu District | 8.57% | 5.47% |

| Futian District | 8.43% | 5.47% |

| Yantian District | 7.59% | 4.66% |

| Nanshan District | 7.23% | 4.65% |

| Baoan District | 3.83% | 2.19% |

| Longgang District | 5.25% | 3.04% |

| Longhua District | 4.09% | 2.26% |

| Pingshan District | 4.44% | 2.49% |

| Guangming District | 3.43% | 1.93% |

| Dapeng New District | 7.00% | 4.41% |

| Urbanized Village Community | Affordable Housing Community | Commercial Housing Community | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Luohu District | Location Map |  |  |  |

| Name | Huangbeiling Community | Guimuyuan Community | Cuizhu Community | |

| Street | Huangbei Street | Guiyuan Street | Cuizhu Street | |

| Scale | 1.27 km2 | 1.65 km2 | 0.78 km2 | |

| Proportion and number of the elderly | 10.1%; 3000 | 11.22%; 6800 | 10.34%; 2900 | |

| Futian District | Location Map |  |  |  |

| Name | Huanggang Community | Xiaomeilin Community | Xiangmihu Community | |

| Street | Futian Street | Meilin Street | Xiangmihu Street | |

| Scale | 1.22 km2 | 1.0 km2 | 0.61 km2 | |

| Proportion and number of the elderly | 7.84%; 2200 | 8.98%; 2100 | 11.89%; 1100 | |

| Nanshan District | Location Map |  |  |  |

| Name | Nanshancun Community | Fuguang Community | Qilin Community | |

| Street | Nanshan Street | Taoyuan Street | Nantou Street | |

| Scale | 1.14 km2 | 1.52 km2 | 0.62 km2 | |

| Proportion and number of the elderly | 7.01%; 1000 | 7.13%; 1000 | 7.97%; 3800 | |

| Information | Option | Number | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 252 | 37.4 |

| Female | 421 | 62.6 | |

| Age | 50–59 | 160 | 23.8 |

| 60–69 | 269 | 40.0 | |

| 70–79 | 166 | 24.7 | |

| 80–89 | 71 | 10.5 | |

| Over 90 | 7 | 1.0 | |

| Education level | Elementary school and below | 199 | 29.6 |

| Middle School to High School | 343 | 51.0 | |

| Bachelor’s degree and above | 131 | 19.4 | |

| Physical condition | Non self-care elderly | 77 | 11.4 |

| Self-care elderly | 596 | 88.6 | |

| Household registration | Non-household elderly | 380 | 56.5 |

| household elderly | 293 | 43.5 | |

| Economic conditions | Low | 293 | 43.5 |

| Medium | 334 | 49.6 | |

| High | 46 | 6.9 |

| QOL Dimension | Number | Question |

|---|---|---|

| Q1. Overall QOL | q1 | How do you rate your quality of life? |

| Q2. Physical QOL | q2 | How well you can move (walk)? |

| q3 | How often are you bothered by illness or physical pain? | |

| q4 | How often do you need medical care? | |

| q5 | How well do you sleep? | |

| q6 | How often do you feel tired? | |

| q7 | How well can you take care of yourself? | |

| q8 | How well do you work? | |

| Q3. Psychological QOL | q9 | What is your attitude toward your future? |

| q10 | How satisfied are you with your present appearance? | |

| q11 | How often do you have negative emotions, such as depression, loneliness, and pessimism? | |

| q12 | How is your memory lately? | |

| q13 | What level of respect do you get from others? | |

| Q4. Social Relationships QOL | q14 | Do you get enough support from your friends? |

| q15 | How is your relationship with your neighbors? | |

| q16 | How often do you have friction with other family members? |

| Content | Construction Factor | Number | Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Functional setting | A1 Function type | a1 | Satisfaction with the diversity of medical care services |

| a2 | Satisfaction with the diversity of life care services | ||

| a3 | Satisfaction with the diversity of social activity services | ||

| A2 Function scale | a4 | Degree of crowding in medical care function rooms | |

| a5 | Degree of crowding in life care function rooms | ||

| a6 | Degree of crowding in social activity function rooms | ||

| B. Planning and layout | B1 Service radius | b1 | Distance from home to the medical care of CECF |

| b2 | Distance from home to the life care of CECF | ||

| b3 | Distance from home to the social activity of CECF | ||

| B2 Walkability | b4 | Satisfaction while walking to CECF | |

| C. Operation and management | C1 Service quality | c1 | Satisfaction with the quality of CECF |

| C2 Service affordability | c2 | Satisfaction with the cost of services in CECF |

| Fitted Indicators | CECF | QOL | Reference Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | 250.835 | 247.200 | - |

| df | 51 | 87 | - |

| χ2/df | 4.918 | 2.841 | <5 |

| RMSEA | 0.076 | 0.052 | <0.08 |

| CFI | 0.962 | 0.968 | >0.9 |

| TLI | 0.951 | 0.962 | >0.9 |

| IFI | 0.963 | 0.968 | >0.9 |

| RFI | 0.940 | 0.942 | >0.9 |

| NFI | 0.954 | 0.952 | >0.9 |

| GFI | 0.942 | 0.954 | >0.9 |

| SRMR | 0.036 | 0.035 | <0.08 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

A, L.; Ma, H.; Wang, M.; Yang, B. Research on Urban Community Elderly Care Facility Based on Quality of Life by SEM: Cases Study of Three Types of Communities in Shenzhen, China. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9661. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159661

A L, Ma H, Wang M, Yang B. Research on Urban Community Elderly Care Facility Based on Quality of Life by SEM: Cases Study of Three Types of Communities in Shenzhen, China. Sustainability. 2022; 14(15):9661. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159661

Chicago/Turabian StyleA, Longduoqi, Hang Ma, Mohan Wang, and Biao Yang. 2022. "Research on Urban Community Elderly Care Facility Based on Quality of Life by SEM: Cases Study of Three Types of Communities in Shenzhen, China" Sustainability 14, no. 15: 9661. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159661