Examining Factors That Influence the International Tourism in Pakistan and Its Nexus with Economic Growth: Evidence from ARDL Approach

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Review of Literature

2.1. Theoretical Support

2.2. Empirical Support

Economic Growth in Nexus with Tourism Development

3. Tourism and Terrorism

4. Inflation and Tourism

5. Methodology

5.1. The Data

5.2. The Variables

6. Statistical Tools

6.1. Testing for Multi-Collinearity

6.2. Testing for Heteroskedasticty

6.3. Unit Root Test

6.4. Cointegration Test

7. Autoregressive Distribution Lag (ARDL)

8. Results and Discussion

8.1. Result of the Unit Root Test

8.2. Result of the Bound ARDL Cointegration Test

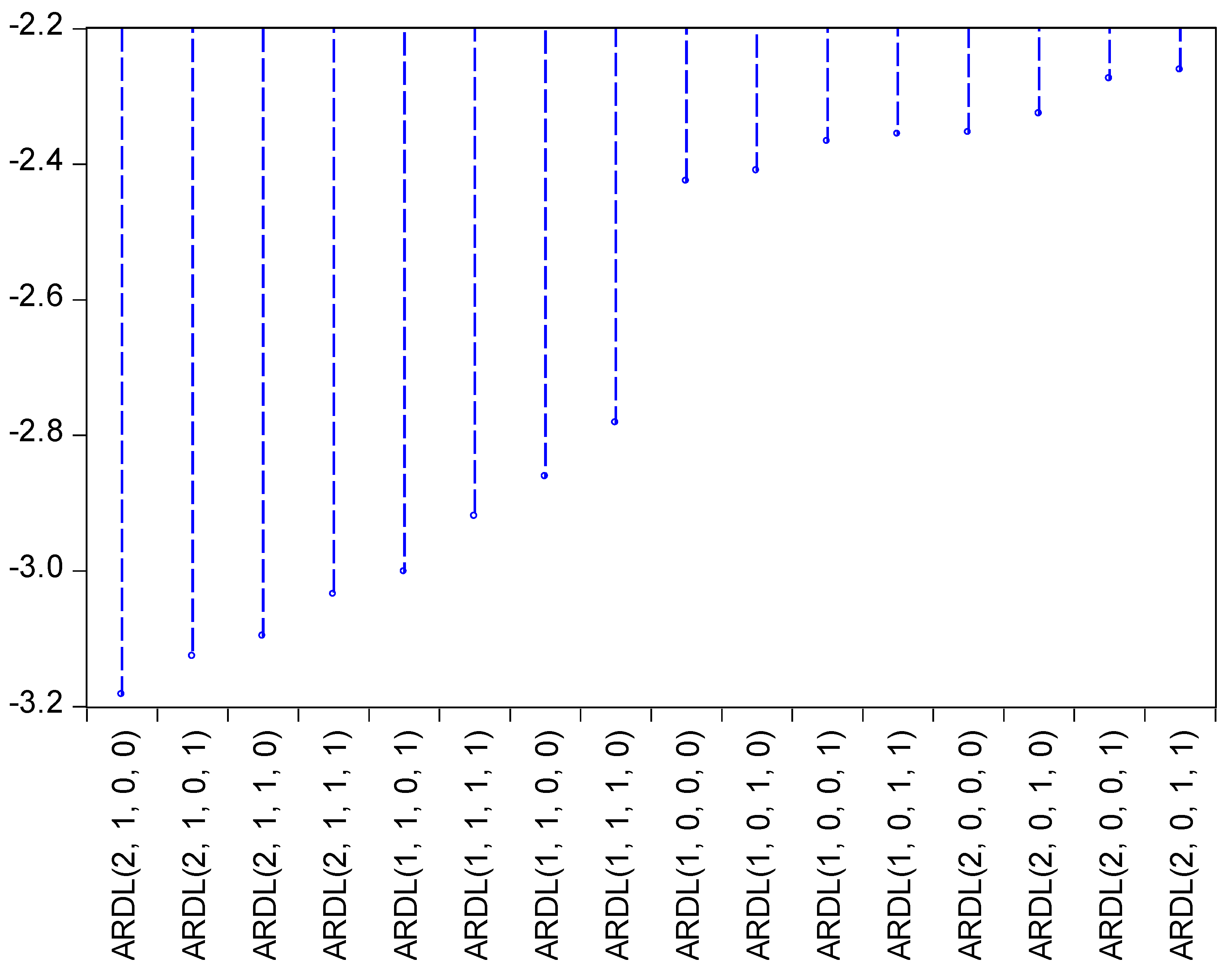

8.3. Model Selection

Graphical Representation of Tourism Expenditure, Tourism Receipt, and GDP Growth throughout the Prescribed Period

9. Conclusions

10. Discussion

11. Limitations and Recommendations of the Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aramberri, J. The host should get lost: Paradigms in the tourism theory. Ann. Tour. Res. 2001, 28, 738–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofronov, B. The development of the travel and tourism industry in the world. Ann. Spiru Haret Univ. Econ. Ser. 2018, 18, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brohman, J. New directions in tourism for third world development. Ann. Tour. Res. 1996, 23, 48–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristea, A. History, Tradition and Continuity in Tourism Development in the European Area. Int. J. Acad. Res. Account. Financ. Manag. Sci. 2012, 2, 178–186. [Google Scholar]

- Dogru, T.; Sirakaya-Turk, E. Engines of tourism’s growth: An examination of efficacy of shift-share regression analysis in South Carolina. Tour. Manag. 2017, 58, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommandru, A.; Espinoza-Maguiña, M.; Ramirez-Asis, E.; Ray, S.; Naved, M.; Guzman-Avalos, M. Role of tourism and hospitality business in economic development. Mater. Today Proc. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido-Fernández, J.I.; Cárdenas-García, P.J. Analyzing the bidirectional relationship between tourism growth and economic development. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 583–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Bibi, S.; Ardito, L.; Lyu, J.; Hayat, H.; Arif, A.M. Revisiting the Dynamics of Tourism, Economic Growth, and Environmental Pollutants in the Emerging Economies—Sustainable Tourism Policy Implications. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tugcu, C.T. Tourism and economic growth nexus revisited: A panel causality analysis for the case of the Mediterranean Region. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, C.C.; Hazari, B.R.; Laffargue, J.P.; Sgro, P.M.; Yu, E.S. Tourism, Dutch disease and welfare in an open dynamic economy. Jpn. Econ. Rev. 2006, 57, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, C.-O. The contribution of tourism development to economic growth in the Korean economy. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, M.I.; Iqbal, M.A.; Shahbaz, M. Pakistan tourism industry and challenges: A review. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2018, 23, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilyas, U.; Tariq, S.; Zafar, F. Tourism towards economic growth of Pakistan. Bull. Bus. Econ. 2017, 6, 92–97. [Google Scholar]

- Ismagilova, G.; Safiullin, L.; Gafurov, I. Using historical heritage as a factor in tourism development. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 188, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aslan, A. Tourism development and economic growth in the Mediterranean countries: Evidence from panel Granger causality tests. Curr. Issues Tour. 2014, 17, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes-Jimenez, I.; Pulina, M. Inbound tourism and long-run economic growth. Curr. Issues Tour. 2010, 13, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharpley, R. Tourism and sustainable development: Exploring the theoretical divide. J. Sustain. Tour. 2000, 8, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schank, R.C. Conceptual dependency: A theory of natural language understanding. Cogn. Psychol. 1972, 3, 552–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, H.; Maqbool, S.; Tarique, M. The relationship between tourism and economic growth among BRICS countries: A panel cointegration analysis. Future Bus. J. 2021, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telfer, D.J. The evolution of tourism and development theory. In Tourism and Development: Concepts and Issues; Sharpley, R., Telfer, D.J., Eds.; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2002; pp. 35–80. [Google Scholar]

- Manzoor, F.; Wei, L.; Asif, M.; Haq, M.Z.U.; Rehman, H.U. The contribution of sustainable tourism to economic growth and employment in Pakistan. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clancy, M.J. Tourism and development; Evidence from Mexico. Ann. Tour. Res. 1999, 26, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, G.; Saha, S. Do political instability, terrorism, and corruption have deterring effects on tourism development even in the presence of UNESCO heritage? A cross-country panel estimate. Tour. Anal. 2013, 18, 587–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brida, J.G.; Cortes-Jimenez, I.; Pulina, M. Has the tourism-led growth hypothesis been validated? A literature review. Curr. Issues Tour. 2016, 19, 394–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mérida, A.; Golpe, A.A. Tourism-led growth revisited for Spain: Causality, business cycles and structural breaks. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojanic, D.C.; Lo, M. A comparison of the moderating effect of tourism reliance on the economic development for islands and other countries. Tour. Manag. 2016, 53, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayissa, B.; Nsiah, C.; Tadesse, B. Research note: Tourism and economic growth in Latin American countries–further empirical evidence. Tour. Econ. 2011, 17, 1365–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paramati, S.R.; Alam, M.S.; Chen, C.-F. The effects of tourism on economic growth and CO2 emissions: A comparison between developed and developing economies. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 712–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brida, J.G.; Pereyra, J.S.; Risso, W.A.; Devesa, M.J.S.; Aguirre, S.Z. The tourism-led growth hypothesis: Empirical evidence from Colombia. Tourismos 2008, 4, 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C.F.; Tan, E.C. How stable is the tourism-led growth hypothesis in Malaysia? Evidence from disaggregated tourism markets. Tour. Manag. 2013, 37, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-C.; Chang, C.-P. Tourism development and economic growth: A closer look at panels. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Brahmasrene, T. Investigating the influence of tourism on economic growth and carbon emissions: Evidence from panel analysis of the European Union. Tour. Manag. 2013, 38, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, P.K. Economic impact of tourism on Fiji’s economy: Empirical evidence from the computable general equilibrium model. Tour. Econ. 2004, 10, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.F.; Tan, E.C. Does tourism effectively stimulate Malaysia’s economic growth? Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamou, A.; Clerides, S. Prospects and limits of tourism-led growth: The international evidence. Rimini Cent. Econ. Anal. WP 2009, 41-09. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brida, J.G.; Lanzilotta, B.; Pizzolon, F. The Dynamic relationship between tourism and economic growth in MERCOSUR countries: A nonlinear approach based on asymmetric time series models. Econ. Bull. 2016, 36, 879–894. [Google Scholar]

- Husein, J.; Kara, S.M. Research note: Re-examining the tourism-led growth hypothesis for Turkey. Tour. Econ. 2011, 17, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, J.E.; Mervar, A. Research note: The tourism–growth nexus in Croatia. Tour. Econ. 2010, 16, 1089–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzel, S.; Tandrayen-Ragoobur, V. Sustainable development and tourism growth in an island economy: A dynamic investigation. J. Policy Res. Tour. Leis. Events 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaguer, J.; Cantavella-Jorda, M. Tourism as a long-run economic growth factor: The Spanish case. Appl. Econ. 2002, 34, 877–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dritsakis, N. Tourism as a long-run economic growth factor: An empirical investigation for Greece using causality analysis. Tour. Econ. 2004, 10, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunduz, L.; Hatemi, J.A. Is the tourism-led growth hypothesis valid for Turkey? Appl. Econ. Lett. 2005, 12, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakotondramaro, H.; Andriamasy, L. Multivariate Granger Causality among tourism, poverty and growth in Madagascar. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 20, 109–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, N.H.M.; Duc, N.H.C.; Dung, N.T. Research note: Empirical assessment of the tourism-led growth hypothesis—The case of Vietnam. Tour. Econ. 2014, 20, 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahiawodzi, A. Tourism earnings and economic growth in Ghana. Br. J. Econ. Financ. Manag. Sci. 2013, 7, 187–202. [Google Scholar]

- Odhiambo, N.M. Tourism development and economic growth in Tanzania: Empirical evidence from the ARDL-bounds testing approach. Econ. Comput. Econ. Cybern. Stud. Res. 2011, 45, 71–83. [Google Scholar]

- Al-mulali, U.; Fereidouni, H.G.; Lee, J.Y.; Mohammed, A.H. Estimating the tourism-led growth hypothesis: A case study of the Middle East countries. Anatolia 2014, 25, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilen, M.; Yilanci, V.; Eryüzlü, H. Tourism development and economic growth: A panel Granger causality analysis in the frequency domain. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridderstaat, J.; Croes, R.; Nijkamp, P. Tourism and long-run economic growth in Aruba. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 472–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgantopoulos, A.G. Tourism expansion and economic development: Var/Vecm analysis and forecasts for the case of India. Asian Econ. Financ. Rev. 2013, 3, 464. [Google Scholar]

- Katircioglu, S. Testing the tourism-led growth hypothesis: The case of Malta. Acta Oecon. 2009, 59, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, P.J.; Klemm, M. The decline of tourism in Northern Ireland: The causes. Tour. Manag. 1993, 14, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfeld, Y.; Pizam, A. Tourism, terrorism, and civil unrest issues. In Tourism Security and Safety; Butterworth-Heinemann: Boston, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bank, W. World Development Indicators United States of America. 2016. Available online: http://data.worldbank.org/country/united-states?view¼chart (accessed on 8 March 2021).

- Chauvin, T.; Engen, H. Terrorism and the Impact on the Economic Growth in France: A Synthetic Control Approach; University of Stavanger: Stavanger, Norway, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Krajňák, T. The effects of terrorism on tourism demand: A systematic review. Tour. Econ. 2021, 27, 1736–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaría, E.C. Terrorism and Tourism: Evidence from a Panel OLS Estimation. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2021, 19, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M. Linkages between inflation, economic growth and terrorism in Pakistan. Econ. Model. 2013, 32, 496–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyder, S.; Akram, N.; Padda, I.U.H. Impact of terrorism on economic development in Pakistan. Pak. Bus. Rev. 2015, 839, 704–722. [Google Scholar]

- Gul, T.G.; Hussain, A.H.; Bangash, S.B.; Khattak, S.W.K. Impact of terrorism on financial markets of Pakistan (2006–2008). Eur. J. Soc. Sci. 2010, 18, 98–108. [Google Scholar]

- Jebabli, I.; Arouri, M.; Teulon, F. On the effects of world stock market and oil price shocks on food prices: An empirical investigation based on TVP-VAR models with stochastic volatility. Energy Econ. 2014, 45, 66–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinbobola, T. The dynamics of money supply, exchange rate and inflation in Nigeria. J. Appl. Financ. Bank. 2012, 2, 117. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Y.C.; Sek, S.K. An examination on the determinants of inflation. J. Econ. Bus. Manag. 2015, 3, 678–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yong, E.-L. Innovation, tourism demand and inflation: Evidence from 14 European countries. J. Econ. Bus. Manag. 2014, 2, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barnet, E.M. The impact of inflation on the travel market. Tour. Rev. 1975, 30, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huseynli, N. Econometric Analysis of the Relationship between Tourism Revenues, Inflation and Economic Growth: The Case of Morocco and South Africa. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2022, 11, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogru, T.; Bulut, U. Is tourism an engine for economic recovery? Theory and empirical evidence. Tour. Manag. 2018, 67, 425–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramatnikovski, S.; Milenkovski, A.; Blazheska, D. The Impact of the International Tourism Receipts on GDP: The Case of Republic of Macedonia. Int. J. Acad. Res. Account. Financ. Manag. Sci. 2016, 6, 220–225. [Google Scholar]

- Sokhanvar, A.; Çiftçioğlu, S.; Javid, E. Another look at tourism-economic development nexus. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 26, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaman, K.A.; Looi, C.N. Economic impact of haze-related air pollution on the tourism industry in Brunei Darussalam. Econ. Anal. Policy 2000, 30, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.M.A. The effects of terrorism on the travel and tourism industry. Int. J. Relig. Tour. Pilgr. 2014, 2, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Van Loon, R.; Rouwendal, J. Travel purpose and expenditure patterns in city tourism: Evidence from the Amsterdam Metropolitan Area. J. Cult. Econ. 2017, 41, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pesaran, M.H.; Smith, R. Estimating long-run relationships from dynamic heterogeneous panels. J. Econom. 1995, 68, 79–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bildirici, M.E.; Kayıkçı, F. Effects of oil production on economic growth in Eurasian countries: Panel ARDL approach. Energy 2013, 49, 156–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salim, R.A.; Hassan, K.; Shafiei, S. Renewable and non-renewable energy consumption and economic activities: Further evidence from OECD countries. Energy Econ. 2014, 44, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 1974, 19, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achyar, D.H.; Hakim, D.B. Cointegration analysis of tourism sector, inflation, interest rate and economic growth in a special autonomy region of Aceh Province, Indonesia. Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2021, 8, 216–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassoun, S.E.S.; Adda, K.S.; Sebbane, A.H. Examining the connection among national tourism expenditure and economic growth in Algeria. Future Bus. J. 2021, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Obs | Mean | Std Dev | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TR | 23 | 0.6433205 | 0.210884 | 0.2869304 | 0.9898611 |

| IN | 23 | 8.034783 | 4.474332 | 2.5 | 20.3 |

| TE | 23 | 14.73739 | 7.756882 | 4.47 | 28.13 |

| TI | 23 | 6.925538 | 1.608548 | 4.094345 | 8.991811 |

| GDPD | 23 | 4.122538 | 1.766771 | 1.014396 | 7.667304 |

| Tl | IN | TE | TR | GDPG | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TI | 1.0000 | ||||

| IN | 0.2836 | 1.0000 | |||

| TE | 0.6547 | 0.0293 | 1.0000 | ||

| TR | −0.8045 | 0.1236 | 0.8215 | 1.0000 | |

| GDPG | −0.0294 | −0.3610 | 0.4143 | 0.1342 | 1.0000 |

| Chi-Square Statistic | Probability |

|---|---|

| 2.60 | 0.1166 |

| Variable | t-Stat | Prob | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| GDPG | −4.27933 * | 0.0034 | I(1) |

| IN | −5.756241 * | 0.0001 | I(1) |

| TE | −4.475321 * | 0.0022 | I(1) |

| TI | −4.068925 * | 0.0054 | I(1) |

| TR | −3.974127 * | 0.00670 | I(1) |

| Significance | Lower Bound I(0) | Upper Bound I(1) |

|---|---|---|

| 10% | 2.72 | 3.77 |

| 5% | 3.23 | 4.35 |

| 2.5% | 3.69 | 4.89 |

| 1% | 4.29 | 5.61 |

| F-Statistics | 4.99 |

| Significance | Lower Bound I(0) | Upper Bound I(1) |

|---|---|---|

| 10% | 4.04 | 4.78 |

| 5% | 4.94 | 5.73 |

| 2.5% | 5.77 | 6.68 |

| 1% | 6.84 | 7.84 |

| F-Statistics | 6.44 |

| Co-Integrating Form | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

| DLOG(TR(−1)) | 0.517828 | 0.192358 | 2.692005 | 0.0175 |

| DLOG(IN) | 0.131166 | 0.028101 | 4.667723 | 0.0004 |

| DLOG(TE) | 0.098339 | 0.029681 | 3.313243 | 0.0051 |

| DLOG(TI) | −0.033743 | 0.013488 | −2.501783 | 0.0124 |

| CointEq(−1) | −0.118687 | 0.059557 | −1.992841 | 0.0661 |

| Long-Coefficient | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

| LOG(IN) | 0.099097 | 0.166998 | 0.593400 | 0.5624 |

| LOG(TE) | 0.828556 | 0.322283 | 2.570895 | 0.0222 |

| LOG(TI) | −0.034743 | 0.013488 | −2.511783 | 0.0224 |

| C | 0.837489 | 0.761495 | 1.099795 | 0.2900 |

| Co-Integrating Form | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

| DLOG(TR) | 4.011404 | 1.718020 | 2.334900 | 0.0525 |

| CointEq(−1) | 0.612875 | 0.206025 | 2.974755 | 0.0081 |

| Long-Coefficient | ||||

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | Prob. |

| LOG(TR) | 1.196539 | 0.535942 | 2.232591 | 0.0743 |

| C | 0.985524 | 0.306824 | 3.212015 | 0.0048 |

| Model | LogL | AIC * | BIC | HQ | Adj. R-Sq | Specification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 40.417671 | −3.182635 | −2.834461 | −3.107073 | 0.985105 | ARDL(2, 1, 0, 0) |

| 3 | 40.822123 | −3.125916 | −2.728003 | −3.039559 | 0.984566 | ARDL(2, 1, 0, 1) |

| 2 | 40.511037 | −3.096289 | −2.698376 | −3.009932 | 0.984102 | ARDL(2, 1, 1, 0) |

| 1 | 40.862655 | −3.034539 | −2.586886 | −2.937386 | 0.983344 | ARDL(2, 1, 1, 1) |

| 11 | 38.514995 | −3.001428 | −2.653254 | −2.925865 | 0.982146 | ARDL(1, 1, 0, 1) |

| 9 | 38.654889 | −2.919513 | −2.521600 | −2.833156 | 0.981027 | ARDL(1, 1, 1, 1) |

| 12 | 36.037563 | −2.860720 | −2.562285 | −2.795952 | 0.978902 | ARDL(1, 1, 0, 0) |

| 10 | 36.208487 | −2.781761 | −2.433587 | −2.706198 | 0.977760 | ARDL(1, 1, 1, 0) |

| 16 | 30.465998 | −2.425333 | −2.176637 | −2.371360 | 0.966376 | ARDL(1, 0, 0, 0) |

| 14 | 31.299940 | −2.409518 | −2.111083 | −2.344750 | 0.966872 | ARDL(1, 0, 1, 0) |

| 15 | 30.852039 | −2.366861 | −2.068426 | −2.302093 | 0.965429 | ARDL(1, 0, 0, 1) |

| 13 | 31.739569 | −2.356149 | −2.007975 | −2.280587 | 0.965962 | ARDL(1, 0, 1, 1) |

| 8 | 30.713978 | −2.353712 | −2.055277 | −2.288944 | 0.964971 | ARDL(2, 0, 0, 0) |

| 6 | 31.422543 | −2.325956 | −1.977782 | −2.250394 | 0.964918 | ARDL(2, 0, 1, 0) |

| 7 | 30.878794 | −2.274171 | −1.925997 | −2.198608 | 0.963054 | ARDL(2, 0, 0, 1) |

| 5 | 31.743687 | −2.261304 | −1.863390 | −2.174946 | 0.963358 | ARDL(2, 0, 1, 1) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khan, N.U.; Alim, W.; Begum, A.; Han, H.; Mohamed, A. Examining Factors That Influence the International Tourism in Pakistan and Its Nexus with Economic Growth: Evidence from ARDL Approach. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9763. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159763

Khan NU, Alim W, Begum A, Han H, Mohamed A. Examining Factors That Influence the International Tourism in Pakistan and Its Nexus with Economic Growth: Evidence from ARDL Approach. Sustainability. 2022; 14(15):9763. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159763

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhan, Naqib Ullah, Wajid Alim, Abida Begum, Heesup Han, and Abdullah Mohamed. 2022. "Examining Factors That Influence the International Tourism in Pakistan and Its Nexus with Economic Growth: Evidence from ARDL Approach" Sustainability 14, no. 15: 9763. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14159763