Abstract

Entrepreneurship ecosystems are dynamic local, social, institutional, and cultural processes and actors that encourage and enhance the formation and growth of new businesses. Thus, this study aims to analyze the importance of sustainable urban development in creating favorable urban conditions in the formation of an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Therefore, a qualitative and exploratory study was carried out, operationalized through a case study. The case of the city of Florianópolis (Santa Catarina State, southern Brazil) was studied in depth; it was intentionally selected considering that it has stood out in terms of investments in innovation, technology, and sustainability, in addition to being a reference for quality of life and for its innovation and entrepreneurial ecosystem. It was possible to know the characteristics of the municipality and the main management practices for sustainable urban development developed in Florianópolis. Above all, among the main findings of this study, from the point of view of urban management, we found that the characteristics present in Florianópolis, as a sustainable city, can benefit the development of an entrepreneurial ecosystem. In this way, by investing in management practices for sustainable urban development, the municipality promotes business growth, new technologies, and entrepreneurship, making the territory more attractive to new investments and talent retention. It was possible to find evidence of urban conditions resulting from these practices capable of favoring the creation of an entrepreneurial ecosystem, among which, the following stand out: (1) social integration and articulation between the actors; (2) high quality of life; (3) capital with the highest human development index in the country; (4) a high rate of green areas; (5) enabling legislation for investments; (6) a city where companies open faster in Brazil and 100% digitally. Among this study’s limitations, the complexity of the analyzed phenomenon and amplitude of the context stand out. In addition, the case study method does not allow for a generalization of the results, as they are related to the case of Florianópolis. Despite this, the research presents a large amount of evidence confirming the theoretical assumption of the study, which is: Sustainable urban development creates favorable conditions for the promotion of an entrepreneurial ecosystem in the city of Florianópolis.

1. Introduction

The construction of urban spaces and the emergence of cities represent an increase in the impacts of human actions on natural resources since urban structures must absorb the new demands of the growing population, adapting to the transformations of society in their production and consumption activities, behaviors, ways of life, and types of relationships, among others. Cities are the great centers of economic development, where knowledge, talent, and diversity are concentrated; human potential is revealed; and proposals for improving the quality of life allied with sustainable development arise, not only for today’s society but also for future generations [1].

In this way, given the importance of the urban environment, as cities provide subsidies for the maintenance of the environment, resources, and living conditions for their residents, the search for intelligent and ecologically oriented alternatives has contributed to the emergence of more sustainable urban environments. In this sense, sustainable development has evolved into a multidimensional approach, that is, the integrated management of economic well-being, environmental quality, institutional capacity, and social well-being [2,3,4,5].

The ultimate challenge for technicians, scholars of urban planning, and public managers is promoting orderly urban development to improve citizens’ quality of life [6]. Creating a favorable local context for entrepreneurship and economic development requires numerous public and private decisions that determine the characteristics of the place [7]. Urban planning through decision-making includes stakeholder engagement, economic development goals, sustainability, and livable communities [8].

When studying the phenomenon of urban policies for entrepreneurship in Poland and Germany, ref. [9] analyzed support knowledge spillovers and entrepreneurship in the large cities of these countries. Using the multiple-case study methodology, the authors identified key factors present in cities for the promotion of entrepreneurship. Among the main findings, the authors discovered the possible relationship between these factors to determine entrepreneurship, which was in line with the literature: agglomeration and industry specialization; quality of life; social, knowledge, and cultural diversity; availability of highly skilled and educated people; spillover and commercialization of knowledge; research universities; infrastructure such as business incubators hosted by universities; innovative clusters; financial incentives to firms that invest in knowledge creation and diffusion. In order for innovative entrepreneurship to develop in an environment, a set of resources must be available that will provide the security and conditions necessary for new businesses to be created and have more chances to grow. The most recent approach to highlighting the conditions demanded by new ventures is entrepreneurship ecosystems [10]. Entrepreneurship ecosystems are dynamic local, social, institutional, and cultural processes that encourage and enhance the formation and growth of new companies [11]. Designing ecosystems means planning environments that form and attract people with knowledge, people with talent (creative people and entrepreneurs), and people with capital in order to mix and generate innovative companies with high growth potential [12].

According to [13], an entrepreneurial ecosystem approach is useful for analyzing how the new coronavirus (COVID-19) affects business. This means that the way communities react in this pandemic era is based on their ability to take advantage of their community spirit [14]. COVID-19 appeared in early 2020 and has significantly changed global society [15]. According to [16], the first surveys on the impacts of COVID-19 in cities were mainly related to four major themes, namely, (1) environmental quality, (2) socioeconomic impacts, (3) management and governance, and (4) transport and urban design. In addition to the humanitarian tragedy of the COVID-19 pandemic, the virus has also significantly impacted local and global economies. Fears about the unpredictable effects of COVID-19 have already significantly influenced the world’s major economies, and many economists are now predicting a recession [17]. The scope of the COVID-19 crisis is unusual and requires entrepreneurial behavior [18].

In this context, in Brazil, Florianópolis, which is the capital of Santa Catarina State and known as the Brazilian Silicon Valley, has stood out in terms of investments in innovation, technology, and sustainability. The city is a reference in quality of life and its innovation and entrepreneurial ecosystem [19]. Based on these considerations, the challenge of understanding the relationship between sustainable urban development (SUD) and entrepreneurship arises, from which some questions emerge: Do sustainable cities present more favorable conditions and encourage entrepreneurship? What urban conditions found in sustainable cities favor the occurrence of entrepreneurship? In Florianópolis, are urban conditions crucial for promoting an entrepreneurial ecosystem in terms of sustainability?

From these questions, the problem of this research arises, defined as follows:

What is the importance of sustainable urban development in creating favorable urban conditions for forming an entrepreneurial ecosystem in Florianópolis?

In order to answer the research problem, this study has the general goal of analyzing the importance of sustainable urban development in creating favorable urban conditions for the formation of an entrepreneurial ecosystem. In this context, this study is justified from the theoretical, social, and urban management points of view. From a theoretical point of view, we sought to contribute to the understanding of sustainable urban development, the characteristics of sustainable cities, and the implications of these characteristics for promoting entrepreneurship, evidencing urban conditions that favor entrepreneurship in cities and providing theoretical support to other researchers and public agencies by facilitating urban planning when related to these factors. From a social point of view, we aimed to demonstrate the benefits that sustainable urban development provides to people who interact with the city, whether professionally, in their work environments, or because they live in it. Finally, from the point of view of urban management, we sought to show public managers the main aspects to be handled in the urban context, in terms of sustainability, to encourage and promote entrepreneurial activity.

Therefore, this paper begins with its theoretical framework regarding sustainable urban development and entrepreneurship in cities. Then, the study method is presented, followed by the results and final remarks.

2. Theoretical Framework

This section addresses the theoretical framework that supports the study. Initially, the perspective of sustainable urban development is presented, and lastly, promoting entrepreneurship in the urban context.

2.1. Sustainable Urban Development

Urbanization is a global phenomenon that affects modern society in different ways; it is a process of population growth with increasing densification in certain areas. This process is accompanied by environmental threats such as increased traffic, air, and noise pollution; the intensification of the urban heat island effect; and the loss of green and blue spaces [20].

Urban growth is closely related to the three dimensions of sustainable development: economic, social, and environmental. When informed by long-term population trends, well-managed urbanization can help maximize agglomeration benefits while minimizing environmental degradation and other potential adverse impacts for an increasing number of city inhabitants [21]. A new agenda, entitled “Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development”, intends to serve as a guide for the international community’s actions in the coming years (2016–2030), thus helping countries achieve sustainable development. The agenda presents 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that list 169 universal goals whose progress is monitored by 232 indicators [21]. The agenda is characterized by guiding national policies and international cooperation to eradicate poverty, expand access to health and food security, promote economic growth, and reduce environmental degradation [22]. These authors also state that the agenda consists of universal objectives and goals that balance the three dimensions of sustainable development (economic, social, and environmental) and involve developed and developing countries.

The global problems that threaten sustainable development are particularly important in urban spaces because urban metabolism systems—as a result of cooperation between city governance policies, infrastructure, and citizens—are deeply dependent on ecosystems and the use of resources [23]. By 2030, SDG Goal 11 aims for cities and, more generally, all human settlements to become inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable spaces. In order to achieve this goal, it is necessary to reorganize societies into several dimensions, mainly on the industrial level and, overall, with respect to the urban lifestyle as it relates to daily consumption and mobility [24]. Planning a sustainable city requires understanding the relationships between the various variables (citizens, services, transport, and energy generation policies, among others) and evaluating their total impact on the local environment, as well as evaluating them more broadly on a regional level. Therefore, to achieve sustainable development in the urban environment, all these factors must be considered and related [25].

While the goals define what is desirable in a specific area of sustainable development, synergy and consistency between the SDGs ultimately depend on setting the right objectives and choosing the right indicators where there are substantive interactions between the SDGs [26]. In this sense, sustainability indicators are instruments that facilitate the daily activities of entrepreneurs and public managers, considering the efficiency and commitment of actions to guarantee future generations the social, environmental, and economic areas [27].

According to the [28], the Sustainable Cities Index encompasses social, environmental, and economic measures. The “people” dimension measures social sustainability, which is the quality of life in the present and prospects for improvement for future generations. According to the [28], factors such as good health and education are key to current social sustainability, and a city’s digital infrastructure will lay the foundation for future quality of life [28]. The “planet” dimension measures a city’s sustainable attributes, including green space and pollution, as well as important environmental mitigation indicators, such as supporting low-carbon transport [28]. The “profit” dimension measures a city’s economic health, incorporating indicators that reflect the productive capacity of cities today, as well as the presence of infrastructure and regulatory enablers that support present and future growth and prosperity [28].

These three pillars are aligned with the UN SDGs. The “people” dimension addresses the SDGs dealing with poverty, health and well-being, education, and reduced inequalities. In contrast, the “planet” dimension addresses the SDGs dealing with clean water and sanitation, clean energy, and climate action. Finally, the SDGs addressed by the “profit” dimension include economic growth, innovation, and infrastructure [28]. Understanding the needs of citizens and how cities work is essential to identify how initiatives to improve sustainability performance can be effectively implemented [28].

According to [29], there is a potential to advance a cultural approach to sustainable urban development by enabling urban “Spaces of Possibilities—SoPs”, relating them to institutional innovations in social, cultural, and political fields. This position is associated with the critical current of sustainable urban development, which maintains that the role of cities is related to the fact that they will be severely affected by the consequences of unsustainable development; e.g., they will face inundations, urban heat islands, the loss of urban ecosystems and species extinctions, supply bottlenecks, increased poverty, epidemics, social conflicts, etc.

The phenomenon described as “neoliberal urbanism” corresponds to urban policies oriented to real estate market logics and aims to provide business opportunities and capital investment in a competition against other cities [30]. In an essentially capitalist view, cities also grow in importance as spaces for capital accumulation, whereby this development needs to be analytically connected to the global dynamics of capital accumulation across places, territories, and scales of the planetary sociospatial landscape [31]. This neoliberal urbanism reinforces urban manifestations of social and ecological unsustainability related to real estate-led urban development and gentrification [29].

Some creative city discourses based on culture-led urban regeneration do integrate elements of sustainability-orientation, opening up a window of real opportunity for SUD-oriented institutional innovations and market-critical “cultural planning” [32,33], not just to legitimize neoliberal political agendas [34,35], but also to pursue countersteering by proposing to strategically reframe and reorient creative city policies toward a SUD-oriented logic in practice [29,36]. Ref. [29] proposed that the cultural sector can develop spaces of possibilities by grounding SoPs in artistic inquiry; involving new audiences to become participants in creative processes; and requiring transversal networking beyond cultural networks. What is more, municipal policy needs to assess its method of contributing to institutional innovations, thus increasing the chances of enabling the emergence of cultural spaces of possibilities for sustainable urban development.

Overall, the search for more sustainable cities requires constructing cities that better generate employment and income opportunities; expand the necessary infrastructure for water and sanitation, transport, information, and communications; seek clean energy alternatives; ensure equal access to services and reduce the number of people living in inadequate conditions; and provide spaces for cultural development. Cities that preserve and value natural and cultural resources are pivotal, and constructing such cities demands competent, sensitive, and responsible governments in charge of their management and urban expansion [25]. In this sense, the next section covers entrepreneurship in cities, presenting concepts and dimensions related to the theme.

2.2. Entrepreneurship in Cities

Cities, both locally and globally, play a strategic role in creating the foundations for knowledge and innovation in the institutional, social, and economic spheres, enabling the emergence of solutions for the most important contemporary social problems [37]. Entrepreneurship plays a vital role in creating and growing businesses and the growth and prosperity of nations and regions [38].

In the 2030 Agenda, entrepreneurship is found in SDG 8, which aims to promote inclusive and sustainable economic growth, employment, and decent work for all. Furthermore, SDG 8 strives to encourage governments and policymakers to rethink and reinvent economic and social policies to end poverty [39]. From the formulation of its goals, SDG 8 is the third most interconnected SDG, having links with SDGs 1, 2, 4, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, and 16 [40]. It is, for example, linked to SDG 12 with respect to sustainable consumption and production through its aim to “decouple economic growth from environmental degradation,” and it is also linked to SDG 10 in reducing inequalities through its target to “protect the labor rights of all workers, including migrant workers” [40]. Entrepreneurship is classified as a social phenomenon associated with transformation, improvement, and sustainable growth for organizations, individuals, and society [41]. According to the same author, this phenomenon emerged to designate people who exercise visionary capacity, identify market opportunities, and assume and manage risks, aiming to generate prosperity—an attitude associated with courage.

To maintain the economy of a country such as Brazil active, it is crucial to be able to create and maintain companies capable of surviving in the market, sustainably generating employment and income, causing the country to increase its production of goods and services, and expanding and improving its general well-being and income distribution [42]. Ref. [43] stated that joint action between society, companies, and the government creates an environment favorable to entrepreneurship since they move capital and human resources to a region. The topic of entrepreneurship involves several perspectives that address the important connections between the entrepreneurship process and local economic and social contexts [44]. As it is unquestionable that external forces are critical for an organization’s performance, influencing and contributing to the competitive advantage of companies, the forces of regional location are explored because they identify that a region can enhance the performance of its resident organizations [45,46,47].

Ref. [48] explored the role of cities in facilitating digital entrepreneurship and overcoming institutional resistance to innovation, suggesting that cities offer an environment that is critical for digital entrepreneurship. The authors concluded that cities present a fertile ground for the creation of new formal and informal institutions. There are several benefits provided in cities, i.e., agglomerations where transaction costs are lowered, a diverse collection of actors are present, policymakers are more accessible, and markets are more diverse. What is more, the density of cities implies that network effects can be generated more efficiently, especially for digital startup and scaleup growth. In the same vein, [49] stated that higher population density has also been linked to higher degrees of inventive output, and some case studies [50] have also suggested that geographic concentration tends to facilitate the diffusion of tacit knowledge.

In this scenario of cooperation and the convergence of a series of factors, entrepreneurial ecosystems emerge, resulting from the interaction between various elements responsible for creating and developing new businesses [51]. Global research indicates that interest in entrepreneurship ecosystems continues to grow as local leaders, public and private, feel increasing pressure to stimulate economic growth by supporting more successful entrepreneurial activities in a given region [52]. The concept of an entrepreneurial ecosystem emphasizes that entrepreneurship takes place in a community of interdependent actors [53]. Ref. [54] defines this ecosystem as a “set of actors, institutions, social structures, and cultural values that produce entrepreneurial activity.” This is driven by innovation habitats that unite talent, technology, capital, and knowledge through private actions or public incentives, such as incubators [55]. This concept expands previous definitions such as “industrial cluster” and “regional innovation systems”, reflecting the importance of a diverse set of actors, external to a company but fundamental to explaining its innovative performance [44].

According to [11], the term “entrepreneurial ecosystem” surpassed other concepts, such as environments for entrepreneurship, which also highlight the mechanisms, institutions, networks, and cultures that support entrepreneurs. Ref. [56] proposed an entrepreneurship ecosystem model composed of six domains: public policies, financial capital, culture, supporting institutions, human resources, and markets. Public policy is recognized as a fundamental instrument that governments can use to foster a nation’s entrepreneurial spirit and economic prosperity [57]. Ref. [56] stated that the dimensions of leadership and government constitute the domain of public policies. These dimensions include social legitimacy, unequivocal support, financial support, regulatory framework, and others. The governmental role, through public policies, is considered essential for the formation of the entrepreneurial ecosystem, as it is believed that, through incentive policies, it is possible to reduce bureaucratic barriers and facilitate entrepreneurial initiatives.

Ref. [58] reported that the regulatory environment has a decisive contribution to entrepreneurship because public managers can adopt regulatory and entrepreneurship policies. The authors cited tax rate reduction, greater access to credit, and entrepreneurial education programs as examples of stimulus. Ref. [56] pointed out that public managers should emphasize the role of local conditions and bottom-up processes; they should emphasize ambitious entrepreneurship, that is, favoring high-impact entrepreneurs and focusing on institutions above all in encouraging entrepreneurial culture development and in establishing a legal, bureaucratic, and regulatory framework favorable for entrepreneurship development.

Ref. [59] reinforced that economic and cultural conditions are factors of the entrepreneurial ecosystem that, in fact, influence the development of new companies. It is important to consider regional characteristics and potentials, as these considerably increase the potential for good results from new companies. Therefore, there are financing mechanisms in the financial capital domain that act in favor of enterprise development, from their birth to their maturation [56]. Nonetheless, ref. [56] identified the cultural domain from two dimensions: success stories and societal norms. The first dimension is related to how individuals interact and articulate in their groups, how they behave in their enterprising activity, and how the attribution of values ahead of success and failure is made. From the author’s perspective, the second dimension involves social norms that guide the perception of individuals in the face of market challenges, risks and errors, experimentation, and creativity.

Ref. [56] defined the support institutions domain as based on three dimensions: infrastructure, support professions, and nongovernmental institutions. The infrastructure dimension refers to local infrastructures such as telecommunications, energy, transport, and logistics. Infrastructure enhances connectivity and links that facilitate recognizing opportunities [60]. The support professions represent the dimension related to professionals who support entrepreneurs, including lawyers, accountants, bankers, and technical guidance services in specific sectors. However, the nongovernmental institution dimension is characterized as a set of institutions formed by civil society as associations to support entrepreneurs. According to the author, the functioning of these elements facilitates the occurrence of entrepreneurial activity. In the Brazilian case, only 14% of entrepreneurs seek some public or private agency to support entrepreneurship, demonstrating the fragility of this pillar for entrepreneurial ecosystems in Brazil [61].

The human resources domain in [56] study is divided into labor dimensions, comprising elements such as trained and untrained labor, and into educational institutions, defined by the existence of the elements universities, technical schools, and specific training programs in the area of entrepreneurship. Briefly, this domain includes entrepreneurs and the general workforce, both of which are qualified through education. The same author conceptualizes the domain’s markets using the initial customers and networks. Initial customers are understood as test groups, preliminarily analyzing the products and services that are offered and distribution channels ready for disseminating new products, distributing them through a national and international network of contacts. Nonetheless, networks are understood as including multinational companies, networks of entrepreneurs, and other networks linked to new businesses [56].

Ref. [56] argued that, in order to promote entrepreneurship development, all areas of the business ecosystem should be organized and operating. However, the author pointed out that it is unnecessary to worry about intervening and changing everything on a complete scale all at once. In the author’s assessment, alteration in one of the domains or some of them means improving the territory’s economic conditions. In other words, an entrepreneurial ecosystem is an environment favorable to entrepreneurship, where entrepreneurs have the resources and help to innovate and make their business prosper [62].

To design ecosystems is to plan environments that form and attract people with knowledge, people with talents (creative people and entrepreneurial ones), and people with capital in order for them to mix and manage, especially, innovative companies with high growth potential [12]. In accordance with this discussion, the next section presents the research method.

3. Materials and Methods

This section presents the classification of the study and the methodological procedures used during the research in order to achieve the proposed objective and answer the research problem: “What is the importance of sustainable urban development in creating favorable urban conditions for the formation of an entrepreneurial ecosystem in Florianópolis?”.

This is an exploratory study with a qualitative approach aiming to highlight the theme studied through an approach that provides greater details of the relationship between the characteristics found in the urban environment in the context of the city of Florianópolis (Santa Catarina State, Brazil) that are capable of promoting entrepreneurship. A case study was conducted [19], which consisted of deeply and exhaustively studying several objects to allow for their detailed understanding. Florianópolis was intentionally selected as it is the second-best city to start a business in Brazil and among the top ten cities in the general placement of smart cities [63]. Additionally, it is among the top ten on specific topics such as technology and innovation, entrepreneurship, education, health, and economics in the ranking of Brazilian smart cities [64].

Data collection occurred by obtaining multiple sources of evidence to later converge the data triangularly, avoiding distortions, especially those resulting from informant bias, producing more stable and reliable results, as recommended by [19]. Hence, the data were obtained through semi-structured interviews, document analysis, and testimonials.

The semi-structured interviews, as indicated by [65], were conducted with a previously defined structure based on [28] and [56], which allowed us to include unstructured questions according to the researcher’s initiative. As for the interviewees, they were selected based on their contribution and relationship with sustainable urban development and entrepreneurship. In this way, managers responsible for urban development and/or linked to the municipal government, as well as representatives of organized civil society, were interviewed. Among the interviewees were representatives of the Florianópolis city hall and the Santa Catarina state government, a representative of the Federal University of Santa Catarina, and a representative of the Santa Catarina Technology Association (ACATE), recognized as an important habitat for entrepreneurship and innovation in Florianópolis. ACATE is the main representative of innovative entrepreneurship in Santa Catarina and has over 1200 member companies. The interviewees are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Interviewees.

The interviews were recorded, fully transcribed, coded, and later analyzed to unveil their meanings through inference and deduction and based on thematic structures, together with other sources of evidence, as indicated by Coffey and Atkinson (1996). Data analysis took place through content analysis, as indicated by [66]; according to the same author, content analysis is a set of communication analysis techniques that use systematic and objective procedures to describe the content of messages [66].

Official documents of the city hall of Florianópolis (CHF) were consulted, among which the Master Plan of Florianópolis and its subsequent revisions and the sectoral plans and the publications of the Institute of Urban Planning of Florianópolis (IUPF) stand out. Other important sources of information came from the Entrepreneurial City Index (2020) by Endeavor; the Sustainable Florianópolis Action Plan (2015); the Citizen Monitoring Network of Florianópolis; news published on the official website of the CHF on the Internet; legislation at the national, state, and municipal levels; research by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE); academic studies; and other documents related to Florianópolis.

Data were interpreted based on the theoretical assumption, comparing empirical data with predicted patterns and benefiting from previous theoretical propositions to guide the analysis, as advised by [19].

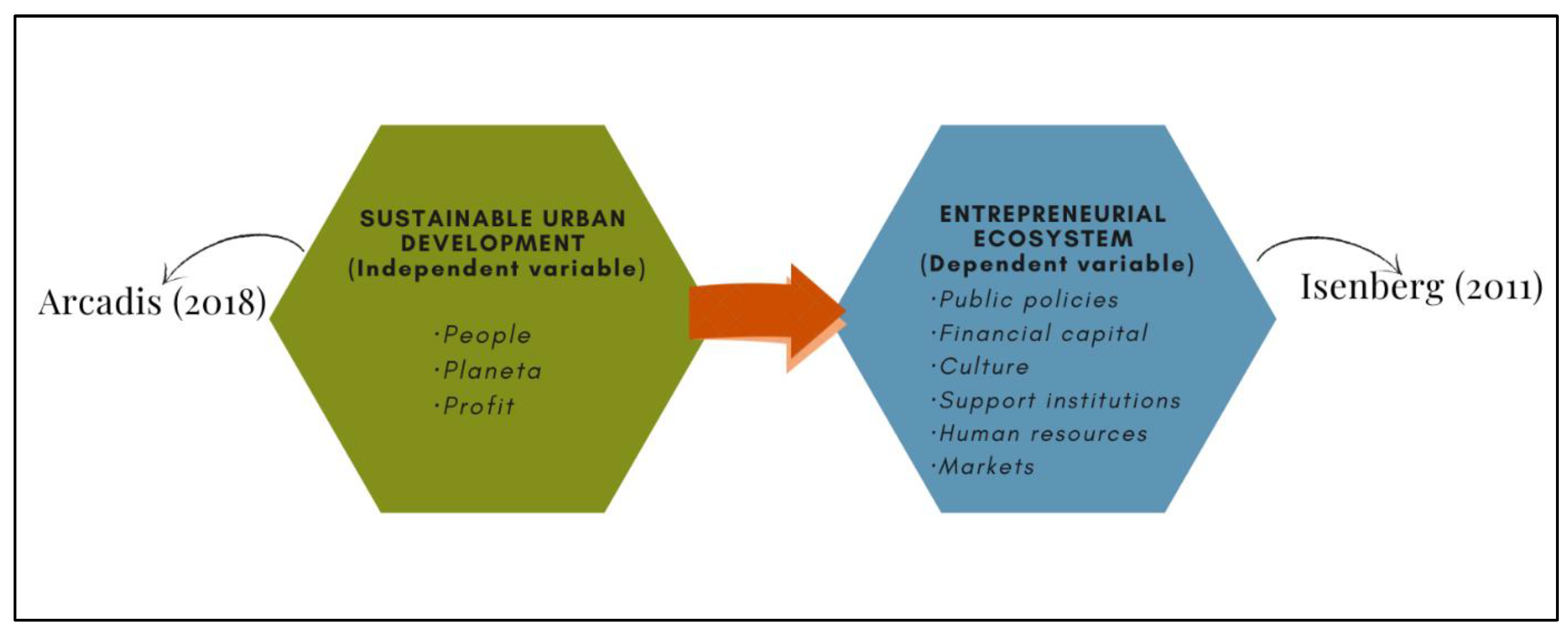

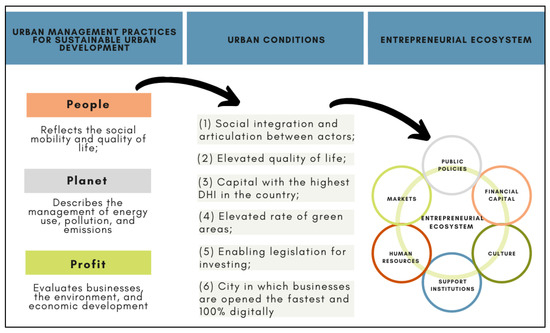

The conceptual model that guided and led this study is outlined in Figure 1, below. The theoretical model of this study indicates the relationship between management practices for sustainable urban development and the creation of urban conditions capable of promoting the formation of an entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the study. Source: Prepared by the authors [28,56].

The analysis categories of the model allowed us to identify aspects of sustainable urban development based on the [28], in which three dimensions were evaluated: (1) people, (2) planet, and (3) profit.

The analysis categories, which identify the entrepreneurship ecosystem, are based on the model developed by [37]. In this sense, business performance was evaluated through the following dimensions: (1) public policies, (2) financial capital, (3) culture, (4) support, (5) human Capital, and (6) markets.

Hence, we sought to verify the theoretical assumption of the study, namely:

Q1: “Sustainable urban development creates favorable conditions for promoting an entrepreneurial ecosystem in Florianópolis.”

In view of this presupposition and built on the basis of the described theoretical framework, data were interpreted from it, comparing the empirical data with patterns predicted in the conceptual model of the study, as recommended by [19].

4. Presentation of Results: The Case of Florianópolis

In this section, the results of the study are presented. Firstly, the profile of the city of Florianópolis is shown. Then, in the second and third subchapters, the dimensions proposed in the conceptual model of this study are analyzed concerning management practices for sustainable urban development and the characteristics of the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Florianópolis while considering the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic in both dimensions. Lastly, it deals with the importance of sustainable urban development in forming the entrepreneurial ecosystem in the case analyzed.

4.1. City Profile and Urban Sustainability

Florianópolis is located in southern Brazil and the capital of Santa Catarina State, also known as “Ilha da Magia” (Magic Island). According to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics [67], it covers 674.844 km2, consisting of an insular part with an area of 426.6 km2, and a continental part, with an area of 11.9 km2, divided into 12 administrative districts. In 2020, the capital had an estimated population of 508,826 people [68].

The United Nations Development Program (UNDP) ranked Florianópolis in 2010 as the Brazilian capital with the best human development in both Brazil and Santa Catarina State, as it occupies the first position in this indicator: 0.847. The city combines elements that facilitate sustainable solutions to promote a better quality of life: concentration of human capital, research and innovation institutions, high human development index (HDI), entrepreneurship culture, and high quality of life [63]. Ref. [69] considered the city a thriving innovation hub that started this trajectory due to the cooperation between the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC), the State University of Santa Catarina (UDESC), and the Federal Institute of Santa Catarina (IFSC). The city and its innovation habitats are currently joined in a triple helix (university, government, and private initiative) to develop entrepreneurship and innovation.

In this sense, management practices for sustainable urban development in Florianópolis were studied by referring to analyses of the three dimensions of the Sustainable Cities Index (people, planet, and profit), which, according to the [28], is a broad measure of sustainability that encompasses social measures and environmental and economic health of cities. What is more, the [28] demonstrated that the “people” pillar measures social sustainability, quality of life in the present, and prospects for improvement for future generations, with the hypothesis that factors such as good health and education are key to current social sustainability and that a city’s digital infrastructure will lay the foundation for future quality of life.

In this sense, according to the interviewees and evidence collected, Florianópolis is nationally recognized for its health system, which is the second most economically important sector of the city. Technology is the city’s main economic sector and is closely linked to quality education, which includes the Escolas do Futuro, two public universities, a federal institute, and thirteen higher education institutions (community and/or private). In the city, there are one hundred and ten graduate courses and seventy-five research groups focused on innovation, knowledge, and entrepreneurship, in addition to professional training.

Florianópolis is considered the best city for business in the service sector according to [70]. The city has high quality of life at work despite a deficiency in urban mobility. In this sense, the “Living Lab Florianópolis” has helped optimize urban management and implement new intelligent services. In addition to being the fastest business-opening city in Brazil with the “Floripa Simples” program, it is possible to open a business in the low-risk category in 4 h in the capital of Santa Catarina.

According to the [28], the “planet” component measures the sustainable attributes of a city, including water supply, sanitation, and air pollution. In Florianópolis, according to the main evidence observed in the interviews and documents referring to this pillar, the water supply is of good quality despite presenting issues in the summer when the population increases, as well as the sewage system, which is at an alert level of 64%. Nonetheless, there are some actions underway in the city to minimize the existence of irregular connections and/or the disposal of sewage, such as the “Floripa Se Liga Na Rede Program”. In addition, the city has a high rate of green areas and there is an incentive to use bicycles and electric vehicles.

What is more, the construction of the first sustainable early childhood education unit in Brazil is evident. Florianópolis received the UNESCO Creative City Chancellor in gastronomy. It seeks to be a zero-waste city and presents studies on mitigation and climate change, natural vulnerability and risk, and urban growth. In this sense, the city is concerned with environmental issues, seeking solutions, and encouraging sustainable practice and culture.

Finally, the “profit” pillar measures a city’s economic health, incorporating indicators that reflect the productive capacity of cities and the presence of infrastructure and regulatory enablers that sustain present and future growth and prosperity [28]. According to Interviewee D, in addition to quality of life, which attracts good talent to the city, Florianópolis presents a good environment to live in, and the taxes for services in Florianópolis (the average rate) is one of the lowest in the country:

“First of all, we have a good quality of life, which attracts good talent, which is the basis of everything. Hence, since we have talented people who choose the city to live in, of course, adding this to the business environment built based on ecosystem associativism, and each propeller of this ecosystem doing its part, we managed to build a good environment to do business. There is also another component closely linked to the business model of these companies, which are part of the economic matrix of Florianópolis. Most of them have their business model based on providing services instead of selling a physical product. Under the Brazilian tax model, these companies pay, among other taxes, the ISS, instead of ICMS, the ISS rate of Florianópolis, the average rate, is one of the lowest in the country, in the range of 2.4%, and this is a wise decision because normally the reaction of governments and, especially in times of crisis, is to increase the tax rate. In Florianópolis, this was never on the agenda because we noticed that the lower rate attracts business and we collect more for the city, which is a very interesting phenomenon” (Interview evidence: Interviewee D—Superintendent of Science, Technology, and Innovation—CHF).

Thus, one can observe the productive capacity of Florianópolis, as it is the capital with the highest HDI in Brazil. Despite its structural deficiency in urban mobility, it has the presence of infrastructure and regulatory facilitators, being the capital of innovation and quality of life and a reference for business environments with the highest density of startups per thousand inhabitants in the country. Moreover, it has one of the lowest average tax rates (2.4%) and is also the city where companies are opened the fastest in Brazil, 100% digitally. Additionally, it has a business environment built on associativism—an ecosystem—and each propeller of this ecosystem supports growth and prosperity in the present and future of the city.

4.2. Entrepreneurial Ecosystem in Florianópolis

In Brazil, Florianópolis has stood out in terms of investments in innovation, technology, and sustainability in addition to being known as the Brazilian Silicon Valley. It is a reference in quality of life for its innovation and entrepreneurial ecosystem [71]. Entrepreneurship ecosystems refer to a set of structural conditions that new ventures must meet during their initial life stage [72]. The term “entrepreneurial ecosystem” is a recent nomenclature associated with the agglomeration of business, innovation, and the relationship between business partners [73]. Ref. [56] proposed an entrepreneurship ecosystem model composed of six domains: public policies, financial capital, culture, supporting institutions, human resources, and markets. The leadership and government dimensions constitute the public policy domain. The governmental role, through public policies, is considered essential for forming an entrepreneurial ecosystem, as it is believed that incentive policies can reduce bureaucratic barriers and facilitate entrepreneurial initiatives [56].

Therefore, among the observed actions, the public policy domain is linked to goal 8.3, which refers to Agenda 2030, aiming to “promote development-oriented policies that support productive activities, decent job creation, entrepreneurship, creativity and innovation, and encourage formalization and the growth of micro, small, and medium enterprises through access to financial services”. The Floripa Empreendedora Program [74] aims to implement planned and integrated actions, enhance the business environment, and promote and foster entrepreneurship and local economic development. The program consists of 13 main lines of action that have public and private partnerships: development actors; an entrepreneur service network; debureaucratization; public purchases; the “Juro Zero Floripa Program” (a microfinance program providing access to credit); the “Exporta Floripa Program” (in order to offer more access to the international market); entrepreneurship in schools; the “Floripa Empreendedora no Bairro” (encouraging the development of neighborhoods); the Florianópolis Economic Development Plan; the Florianópolis Entrepreneurship Center; “Florianópolis em Números” (public information and official and comparative statistical data); opportunities; and an export qualification program.

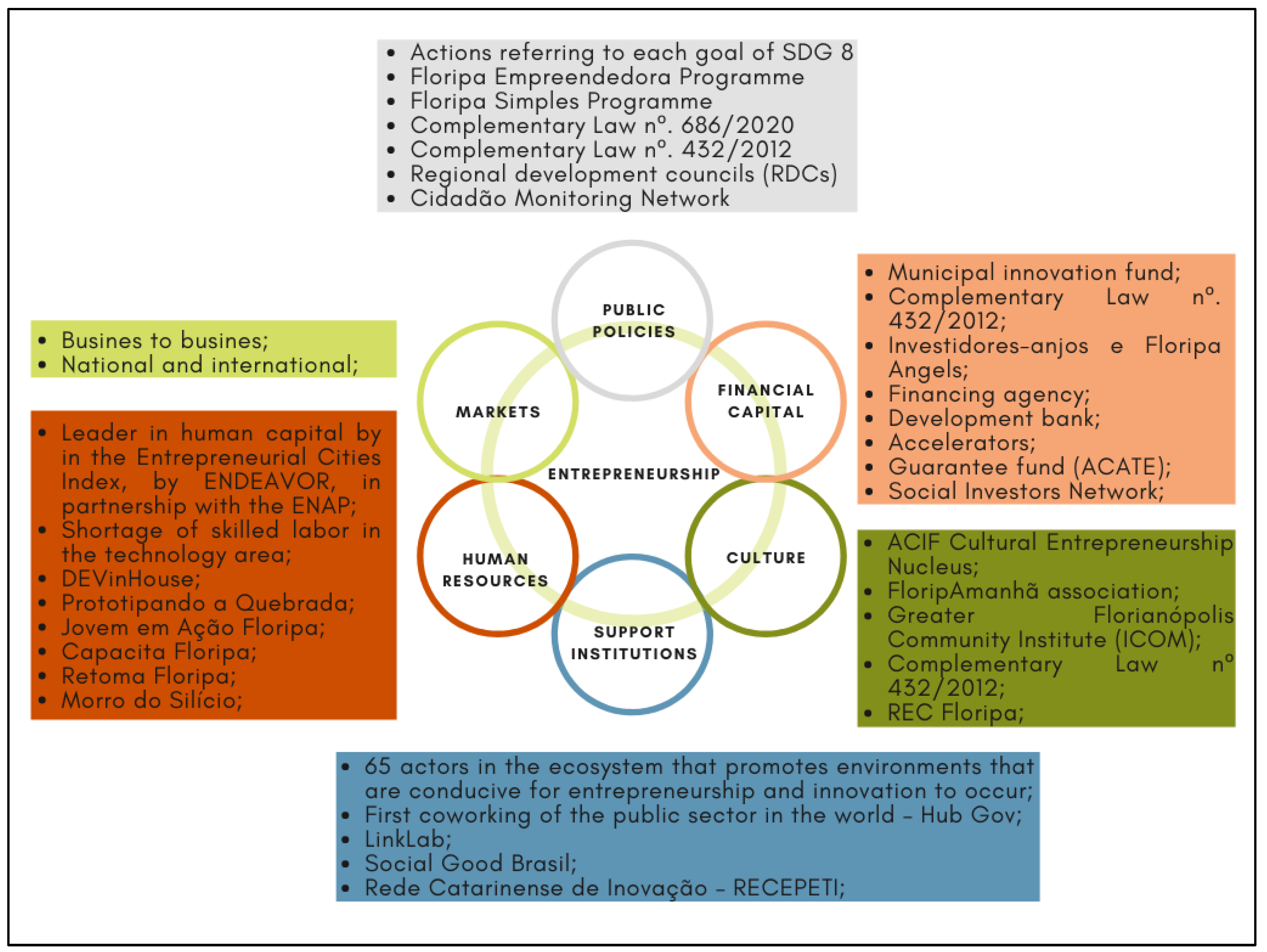

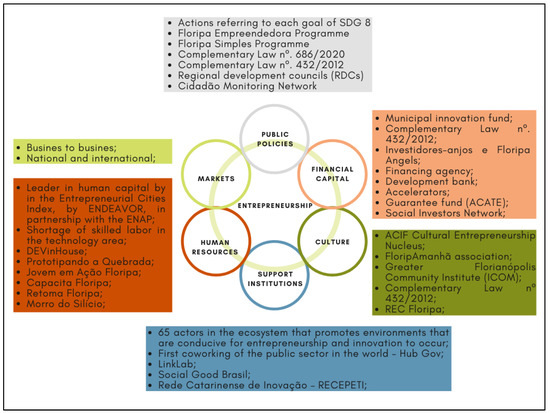

In this sense, the entrepreneurial ecosystem of Florianópolis is in line with the model proposed by [56]), as presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Entrepreneurship ecosystem in Florianópolis. Source: Prepared by the authors.

As for the public policy domain, municipal legislation has incentive policies enabling the reduction of bureaucratic barriers and facilitating entrepreneurial initiatives. In 2021, Planning Bodies, via coordination with the IUPF, requested the revision of points in the Master Plan of Florianópolis in order to bring the practice closer to its objectives of social, environmental, and economic balance, especially due to the urgency proclaimed by the city given the economic and social impacts arising from the pandemic scenario [75]. In this sense, the municipality created the Regional Development Councils (RDCs) to build participatory governance. Over 300 associations are part of the CDRs, which meet monthly to discuss solutions to the city’s problems.

In addition, the Citizen Monitoring Network seeks to improve the population’s quality of life by disseminating the municipal government’s objective indicators and coordinated actions involving the discussion of public policies from the Annual Progress Report on Indicators, to be released annually by the Network. These actions are carried out with the support of different actors in the ecosystem in favor of a more humane, innovative, and entrepreneurial city.

In this sense, referring to the financial capital domain, the city has the Municipal Innovation Law, which establishes instruments to support and stimulate the development of technological hubs, the knowledge industry, and innovative ventures in Florianópolis. This law was created based on the need for public authorities to find solutions to economic, social, and environmental challenges. The law creates mechanisms to stimulate innovation, such as public calls, research grants, and financial resources for entrepreneurial projects [76]. In addition, there is support from angel investors, financing agencies, development banks, accelerators, the ACATE Guarantee Fund, and the Social Investors Network, which are part of the financial capital domain.

As for the cultural domain, the ACIF Cultural Entrepreneurship Nucleus, the Floripa Amanhã Association, the Greater Florianópolis Community Institute, and the Florianópolis Creative Economy Network stand out. Hence, this ecosystem has incentives and support from both the private and public sectors.

When analyzing the support institutions domain, Florianópolis has parks, innovation centers, pre-incubators, incubators, accelerators, technological innovation centers, coworking, and creative district initiatives. In all, 65 actors in the ecosystem promote favorable environments for innovation and entrepreneurship [77]. In addition, the world’s first public sector coworking space was inaugurated—Hub Gov, which has the participation of public servants from various institutions. The LinkLab initiative of the Santa Catarina Association of Technology Companies was also launched, which seeks to solve the challenges by bringing market startups and large companies closer to innovative solutions [78].

These results are in line with [48], who stated that cities contribute to digital entrepreneurship by offering the field conditions required for the accomplishment of changes to both formal and informal institutions and in order to avoid regulatory capture. For the authors, cities offer proximity to key actors in the field, including suppliers, regulators, politicians, and institutional entrepreneurs, making it possible for them to interact continuously. This scenario of building trust and resolving ambiguities is also verified in Florianópolis.

In the human resources domain, Florianópolis stands out as a leader in human capital in the Entrepreneurial Cities Index by ENDEAVOR, in partnership with the National School of Public Administration (ENAP); nonetheless, the city has a shortage of skilled labor in the technology area. Programs such as DEVinHouse—which accelerates the training of software developers and meets the demands of the information technology sector—and Prototipando a Quebrada—a technological and professional education project that operates in a network in the outskirts, communities, and slums of Florianópolis—were launched to solve this and other problems related to this domain. What is more, the attraction and concentration of qualified people are crucial for the local ecosystem, especially in the case of Florianópolis, where digital entrepreneurship is predominant. This fact corroborates the findings of [48], who note that the relative density and diversity of cities constitute a critical enabling condition for digital entrepreneurship. Access to venture capital and skilled labor makes it possible to build competencies in those settings where skill renewal is critical. Furthermore, it seems like network effects are more easily generated in a dense agglomeration.

Lastly, in the market domain, “business to business” stands out; that is, companies from the Florianópolis ecosystem become initial customers, creating solutions and testing their products and later gaining recognition in other places, as in the case of the RD Station company, which operates in Brazil (mostly Florianópolis and São Paulo), Colombia, Mexico, and the USA, and was recently sold, causing the largest private M&A transaction in the software area of the country [79].

Thus, the next section presents the urban conditions of Florianópolis capable of promoting the formation of an entrepreneurial ecosystem.

4.3. Present Urban Conditions Capable of Promoting the Formation of an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem

Achieving and sustaining growth and entrepreneurship depends on the effective work of multiple and interconnected actors, such as governments, the private sector, society, universities, entrepreneurs, and many others [72,80].

In recent years, Florianópolis has been diversifying its economic activities, becoming known worldwide as a tourist destination with high levels of education and safety and for its entrepreneurial vocation. According to the Entrepreneurial Cities Index by Endeavor Brasil—a national branch of a North American NGO that studies entrepreneurial behavior—investments in the technology sector began in the 1980s, and since then, Florianópolis has been the Brazilian city with the highest economic growth. This growth constantly attracts highly qualified companies and professionals from all over Brazil and abroad [81].

Considering the management practices for sustainable urban development and the characteristics of the city’s entrepreneurial ecosystem, as previously described herein, the main conditioning factors can be highlighted, which can promote the formation of the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Florianópolis.

According to Interviewee D, the main characteristics of Florianópolis make it a sustainable city because of its thriving economic development, social status among the best in the country, and preserved environment:

“I believe that the first characteristic is that we have an economy that has constantly been growing in recent years, even with the crises. If we look at the 2015 crisis and now the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, even so, the city’s economy remains strong. Of course, some areas felt it more than others, but we can see that due to the city’s economic matrix—which is virtually based on services—the economy didn’t feel that much of an effect. Speaking of social issues, compared to other Brazilian cities, we have fewer social problems. Of course, we’re in Brazil, and with all the problems that the country has, we still have a lot to evolve, but compared to other cities, we are doing very well and proof of this is that we have the highest municipal HDI of all capitals in Brazil, and due to the city’s own economic matrix, and the very regulation of activities here, for example, not allowing heavy industries, we have a very adequate environmental preservation, that is, 52% of the city is a permanent preservation area. So, you can say that Florianópolis is a sustainable city because of that, strong economic development, a social condition among the best in the country, and preserved environment.” (Interview evidence: Interviewee D—Superintendent of Science, Technology, and Innovation (PMF)).

According to [82], for a municipality to be considered sustainable, it must avoid the degradation of its environmental system, reduce social inequalities, and provide its inhabitants with a healthy and safe environment, as well as articulate public policies and citizenship actions that allow it to face present challenges and future ones; these are, therefore, the most appropriate measures for local sustainability, that is, those related to public policies integrating the social, environmental, economic, and institutional dimensions.

Mason and Brown [83] argued that entrepreneurial ecosystems emerged in “places that already have an established and highly regarded knowledge base that employs significant numbers of scientists and engineers” and that there is technology disruption that creates new opportunities.

Isenberg [56] defined an entrepreneurial ecosystem as the structure that arises and develops when self-sustaining entrepreneurship occurs regularly and consistently. Florianópolis has invested in programs that enhance the business environment, valuing skills development and strengthening companies in the city. It dynamically promotes economic growth based on the SDGs, as established by the United Nations Assembly [81]. In this sense, Interviewee F commented on the maturity of the city’s entrepreneurial ecosystem, which ends up serving as a reference in supporting the development of other municipalities in the state and Brazil:

“The entrepreneurial ecosystem here in Floripa is very mature. Today, we only have programs linked to ACATE, which is the institution I work for. There are four innovation centers; there are incubators, there are three incubators in the city, as far as I know, there are three accelerators, there are Espaço Maker, Cocreation, and Innovation Incentive Laws, so the ecosystem, as I mentioned to you, the authors, all the authors, and the dimensions of the Florianópolis ecosystem are very well represented, both by academia and companies, such as public and private institutions. So the ecosystem here is overdeveloped, mature, and so much so that we end up serving as a reference in supporting the development of other municipalities in the state and Brazil” (Interview evidence: Interviewee F—Integration Coordinator, Associação Catarinense de Tecnologia (ACATE)).

The underlying idea is that companies not only compete with each other through well-developed autonomous strategies to gain advantages over their rivals—relying solely on their resources, knowledge, and capabilities—but also base their business models on shared resources, network externalities, knowledge spillovers, local endowments and government support [84].

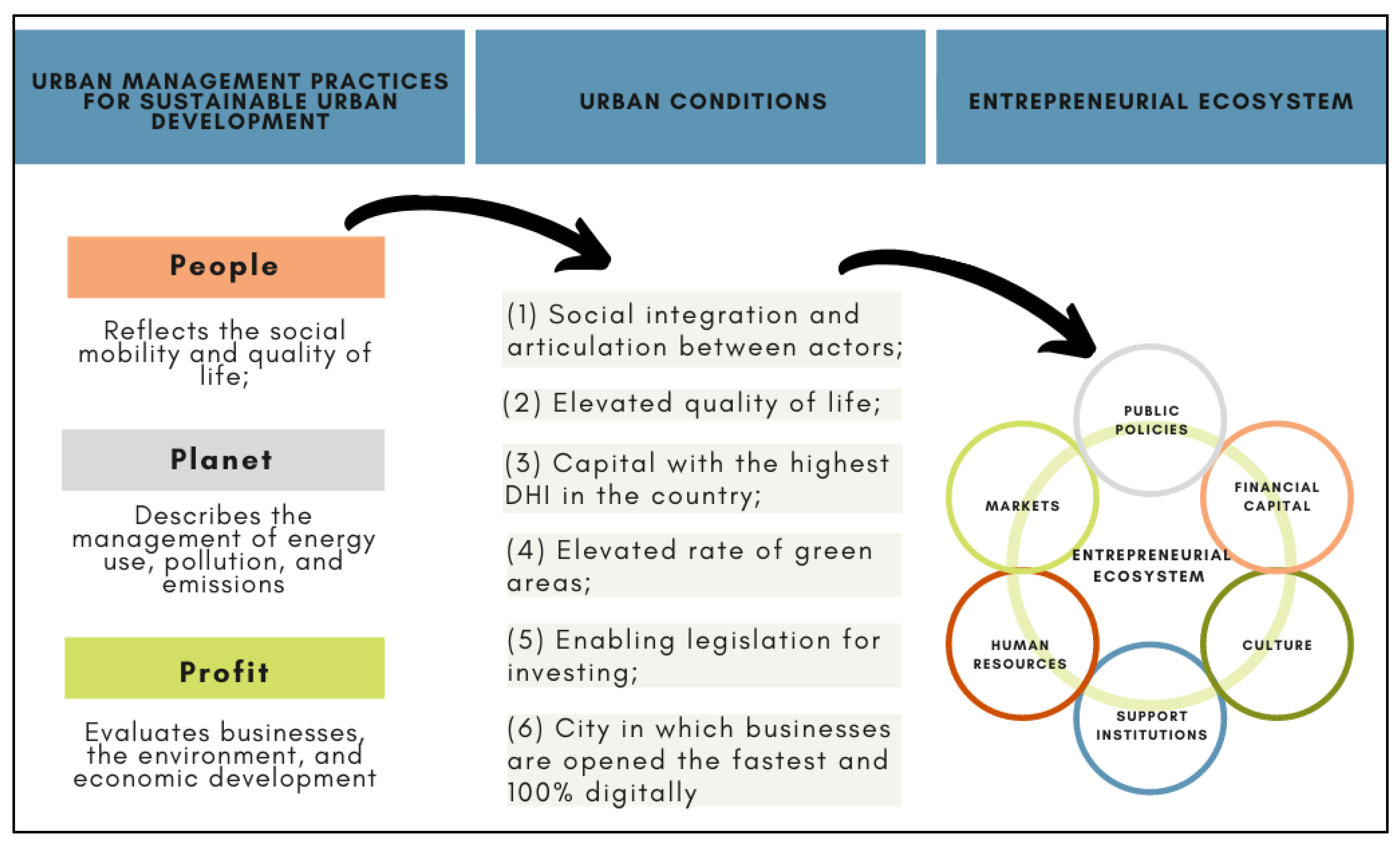

In this sense, certain conditioning factors were identified for the formation of an entrepreneurial ecosystem in Florianópolis, which were provided through policies and management practices aimed at sustainable urban development. As has been evidenced, the following aspects are among the main urban conditions in Florianópolis: (1) social integration and articulation between actors; (2) high quality of life; (3) capital of the highest HDI in Brazil; (4) high rate of green areas; (5) enabling legislation for investments; and (6) a city where companies open faster in Brazil, 100% digitally. Thus, Figure 3 shows the association between management practices for sustainable urban development and urban conditions that favor the formation of an entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Figure 3.

Urban management practices for sustainable urban development, urban conditions, and the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Source: Prepared by the authors.

Social integration and articulation between actors are urban conditions present in Florianópolis, resulting from policies and programs that cover the three dimensions of sustainable urban development, such as Living Lab Florianópolis, a living laboratory in the city that enables the optimization of urban management and the implementation of new intelligent, sustainable services, and social interaction, creating favorable conditions for promoting an entrepreneurial ecosystem. These urban characteristics are added to other aspects of the city, including the high quality of life, another evident conditioning aspect, as well as quality health and education systems since the city has Escolas do Futuro (Schools of the Future), two public universities, a federal institute, and thirteen higher education institutions (public and/or private). Furthermore, there are 110 graduate courses and 65 research groups focused on innovation, knowledge, entrepreneurship, and professional training, which contribute to Florianópolis being the capital with the highest HDI in the country (0.847). Additionally, the city has a high rate of green areas, contributing to citizens’ quality of life and attracting new ventures.

Regulatory aspects were also highlighted (e.g., the municipal legislation of Florianópolis), which has facilitators for investments, allowing ideas to take off and become promising businesses for the city, being the capital of innovation and quality of life and a reference for business environments. The city thus assumes leadership in terms of the density of startups per thousand inhabitants in the country and opens companies faster in Brazil, 100% digitally.

Therefore, one can perceive that certain urban conditions found in Floranópolis, which are the result of management practices for sustainable urban development, are associated with the formation of an entrepreneurial ecosystem. In the case of a sustainable city, Florianópolis proved to be an urban environment capable of promoting such conditions, which create positive externalities that favor an increase in entrepreneurial capacity, which is supported by authors including [1,56,71,82], among others. In this sense, it is possible to state that there is evidence to confirm the theoretical assumption of this study: Q1: “Sustainable urban development creates favorable conditions for the promotion of an entrepreneurial ecosystem in Florianópolis”.

It should be noted that, despite our findings and recent efforts, there are areas to be improved regarding urban development and its entrepreneurial ecosystem. It is known that, because it is in the context of a developing country, there are characteristic challenges to achieving urban sustainability and, consequently, to expanding the benefits of the city with respect to the creation of urban conditions favorable to entrepreneurship and attracting investment. For example, basic sanitation, public security, and urban mobility. Hence, based on the results presented, it is possible to reach the conclusions of this paper, as described in the next section.

5. Conclusions

The present study aimed to analyze the importance of sustainable urban development in creating favorable urban conditions to form an entrepreneurial ecosystem in the city of Florianópolis, Santa Catarina State. In this sense, certain conditioning factors were identified to form an entrepreneurial ecosystem in the city, which were provided through policies and management practices aimed at sustainable urban development. Therefore, in the analyzed context, this study suggests the existence of evidence to confirm the theoretical assumption presented herein, namely: Sustainable urban development creates favorable conditions for promoting an entrepreneurial ecosystem in Florianópolis. Given this context, one can conclude that, in the context of sustainable cities, urban conditions can be favorable for promoting an entrepreneurial ecosystem in Florianópolis.

The qualitative method allowed greater depth and detailing of the results to highlight the theme studied, that is, the relationship between the characteristics found in the urban environment in the context of Florianópolis that are capable of promoting entrepreneurship. To this end, the interviewees were selected based on their contributions to and relationship with sustainable urban development and entrepreneurship. In this way, managers responsible for urban development, linked to the municipal government, as well as representatives of organized civil society, were interviewed. Among the interviewees were representatives of the Florianópolis city hall and the Santa Catarina state government, a representative of the Federal University of Santa Catarina, and a representative of the Santa Catarina Technology Association, which is recognized as an important habitat for entrepreneurship and innovation in Florianópolis. Data collection took place by obtaining multiple sources of evidence so that the data could converge in a triangular fashion. Subsequently, the results of the interviews were added to secondary data, such as documents and statistical data.

The limitation regarding the phenomenon’s complexity and the context’s breadth was also highlighted. There were limitations associated with the case study method, which does not allow for the generalization of the results since they are related only to the case of Florianópolis. In addition, the study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which made it difficult to expand data collection given the restrictions imposed. Nonetheless, we suggest further investigating this theme in Florianópolis through other research strategies, which contemplate different perspectives and methodologies from those used in this work.

For future research, based on the results obtained herein, we also suggest analyzing practices and urban conditions found in other sustainable cities in order to contribute to the advancement of sustainable urban development and the formation of an entrepreneurial ecosystem in other cities, thereby promoting entrepreneurship in Brazil. Furthermore, we recommend planning studies using other research strategies to verify the relationship between urban management practices for sustainable urban development and the formation of entrepreneur ecosystems in other urban contexts.

Finally, the contributions of the data provided herein are highlighted in view of the results that were found. Initially, from the point of view of urban management, we found that the characteristics present in sustainable cities can benefit the development of an entrepreneurial ecosystem. In this way, by investing in management practices for sustainable urban development, the municipality can promote business growth, new technologies, and entrepreneurship, making the territory more attractive to new investments and talent retention.

From a social point of view, the study also demonstrates the benefits that sustainable urban development provides to people who interact with the city, whether professionally in their work environments or because they live in it. The theoretical contributions of this study are also mentioned. Our findings contribute to advancing knowledge in the context of sustainable cities, given that management practices for sustainable urban development and the different urban conditions provided by them were analyzed. In particular, the importance of management practices that favor the formation of an entrepreneurial ecosystem was highlighted, which can be considered a relevant academic contribution in the context of urban sustainability.

Author Contributions

Investigation, G.D.; Supervision, R.S.B., C.M.G. and J.M.K.; Validation, I.K.; Writing—review & editing, C.R.R.d.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request due to restrictions e.g., privacy or ethical.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Leite, C.; Awad, J.C.M. Cidades Sustentáveis, Cidades Inteligentes: Desenvolvimento Sustentável num Planeta Urbano; Bookman: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Alyami, Y.R. Sustainable building assessment tool development approach. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2012, 5, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhringer, J. Measuring the immeasurable—A survey of sustainability índices. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 63, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, A.L. Achievements and gaps in indicators for sustainability. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 17, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmour, D.; Blackwood, D.; Banks, L.; Wilson, F. Sustainable development indicators for major infrastructure projects. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Munic. Eng. 2011, 164, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelidou, M.; Psaltoglou, A.; Komninos, N.; Kakderi, C.; Tsarchopoulos, P.; Panori, A. Enhancing sustainable urban development through smart city applications. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2018, 9, 146–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, M.P. The character of innovative places: Entrepreneurial strategy, economic development, and prosperity. Small Bus. Econ. 2014, 43, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, A.; Shigetomi, Y. Developing National Frameworks for inclusive sustainable development incorporating lifestyle factor importance. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 200, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szulczewska-Remi, A.; Nowak-Mizgalska, H. Who really acts as an entrepreneur in the science commercialisation process: The role of knowledge transfer intermediary organisations. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2021. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isenberg, D.J. Worthless, Impossible and Stupid: How Contrarian Entrepreneurs Create and Capture Extraordinary Value; Harvard Review Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Malecki, E.J. Entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial ecosystems. Geogr. Compass 2018, 12, e12359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.E.; Shooter, S.B. Big: Uniting the University Innovation Ecosystem; American Society for Engineering Education: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ratten, V. Coronavirus e negócios internacionais: Uma perspectiva de ecossistema empreendedor. Thunderbird Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 62, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratten, V. Coronavirus (COVID-19) and the entrepreneurship education community. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2020, 14, 753–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnell, D.; Widdop, P.; Bond, A.; Wilson, R. COVID-19, Networks and Sport Gerenciando Esporte e Lazer na Imprensa. 2020. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_743036/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Sharifi, A.; Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R. The COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts on cities and major lessons for urban planning, design, and management. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 142391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Análise Global de Dados. Briefing Executivo do Coronavírus (COVID-19) Dados Globais. 2020. Available online: https://www.globaldata.com/covid-19/ (accessed on 17 August 2019).

- Leung, T.; Sharma, P.; Adithiyangkul, P.; Hosie, P. Gender equity and public health outcomes: The COVID-19 Experience. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Haase, D.; Kabisch, S.; Haase, A.; Andersson, E.; Banzhaf, E.; Baró, F.; Brenck, M.; Fischer, L.K.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Kabisch, N.; et al. Greening cities—To be socially inclusive? About the alleged paradox of society and ecology in cities. Habitat Int. 2017, 64, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. 2018 Revision of World Urbanization Prospects; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Available online: https://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/ (accessed on 30 July 2018).

- da Silva, A.V.B.; Serralvo, F.A.; Romaro, P. Competitividade da América Latina—Um Estudo à Luz do Modelo Porteriano. Rev. Científica Hermes 2016, 15, 198–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. In-Depth Report: Indicators for Sustainable Cities 2015. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/integration/research/newsalert/pdf/indicators_for_sustainable_cities_IR12_en.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Oliveira, G.M.; Vidal, D.G.; Ferraz, M.P. Urban lifestyles and consumption patterns. In Sustainable Cities and Communities. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bichueti, R.S. Fatores que Condicionam a Formação de Ambientes Urbanos Inovadores em Cidades Sustentáveis. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Santa Maria, Brazil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Conselho Internacional para a Ciência (ICSU). Um Guia para Interações “ODS”: Da Ciência à Implementação; Conselho Internacional para a Ciência (ICSU): Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Galante, C.; Mazzioni, S.; Di Domenico, D.; Ronning, C. Análise dos Indicadores de Sustentabilidade nos Municípios do Oeste de Santa Catarina. Available online: http://dvl.ccn.ufsc.br/congresso_internacional/anais/6CCF/27_15.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Arcadis. Sustainable Cities Index 2018. 2020. Available online: https://www.arcadis.com/en/united-states/our-perspectives/sustainable-cities-index-2018/united-states/ (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Kagan, S.; Hauerwaas, A.; Holz, V.; Wedler, P. Culture in sustainable urban development: Practices and policies for spaces of possibility and institutional innovations. City Cult. Soc. 2018, 13, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castree, N.; Kitchin, R.; Rogers, A. Neoliberalism. In Dictionary of Human Geography; Castree, N., Kitchin, R., Rogers, A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 339–340. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, N. Theses on urbanization. Public Cult. 2013, 25, 86–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, F. Cultural planning in post-industrial societies. In Cultural Planning; Østergaard, K., Ed.; Report from Conference at Centre for Urbanism; The Royal Academy of Fine Arts, the Royal Danish School of Architecture: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2004; pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- Landry, C. The Art of City Making; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterton, P. Will the real creative city please stand up? City 2000, 4, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponzini, D.; Rossi, U. Becoming a creative city: The entrepreneurial mayor, network politics and the promise of an urban renaissance. Urban Stud. 2010, 47, 1037–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, A.J. Capitalism and urbanization in a new key? The cognitive-cultural dimension. Soc. Forces 2007, 85, 1465–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkki, S. Cities for Solving Societal challenges: Towards Human-centric Socio-economic Development? Interdiscip. Stud. J. 2014, 3, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hisrich, R.D.; Peters, M.P.; Shepherd, D.A. Empreendedorismo, 9th ed.; Bookman: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Coscieme, L.; Mortensen, L.F.; Anderson, S.; Ward, J.; Donohue, I.; Sutton, P.C. Going beyond Gross Domestic Product as an indicator to bring coherence to the Sustainable Development Goals. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 248, 119232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Blanc, D. Towards Integration at Last? The Sustainable Development Goals as a Network of Targets. Sustain. Dev. 2015, 23, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcanti, F.R. Processo de Empreendedorismo Inovador no Polo Tecnológico de Florianópolis no Período de 1987 a 2012. Master’s Thesis, Universidade do Sul de Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, Brazil, 2013; 142p. [Google Scholar]

- Dornelas, J.C.A. Empreendedorismo: Transformando Ideias em Negócios, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo, M.D.; Leite, E.F. Cidades Empreendedoras: As novas visões sobre planejamento urbano e desenvolvimento econômico no Brasil. Rev. Eletrônica Adm. (REad) 2006, 12, 266–291. [Google Scholar]

- Spigel, B.; Harrison, R. Toward a process theory of entrepreneurial ecosystem. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2017, 12, 151–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.; Porter, M.E.; Stern, S. Clusters, Convergence, and Economic Performance. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1785–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotopoulos, G.; Storey, D.J. Public Policies to Enhance Regional Entrepreneurship: Another Programme Failing to Deliver? Small Bus. Econ. 2018, 53, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. The Competitive Advantage of Nations; Free Press: Nova York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Geissinger, A.; Laurell, C.; Sandström, C.; Eriksson, K.; Nykvist, R. Digital entrepreneurship and field conditions for institutional change—Investigating the enabling role of cities. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2019, 146, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlino, G.A.; Chatterjee, S.; Hunt, R.M. Urban density and the rate of invention. J. Urban Econ. 2007, 61, 389–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxenian, A. Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, M.C.F.R. The Software Startups Ecosystem of São Paulo, Brazil. Master’s Thesis, Instituto de Matemática e Estatística, São Paulo, Brazil, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Foster, G.; Shimizu, C. Entrepreneurial Ecosystems around the Globe and Company Growth Dynamics; Report Summary for the Annual Meeting of the New Champions 2013; World Economic Forum: Cologny, Switzerland, 2013; pp. 1–36. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_EntrepreneurialEcosystems_Report_2013.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Stam, E. Entrepreneurial ecosystems and regional policy: A sympathetic critique. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 1759–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roundy, P.T. Start-up Community Narratives: The Discursive Construction of Entrepreneurial Ecosystems. J. Entrep. 2016, 25, 232–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, C.S.; Almeida, C.G.; Ferreira, M.C.Z. Habitats de Inovação: Alinhamento Conceitual; Perse: São Paulo, Brazil, 2016; Available online: http://via.ufsc.br/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/e-book-habitats-de-inovacao.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Isenberg, D.J. The Entrepreneurship Ecosystem Strategy as a New Paradigm for Economic Policy: Principles for Cultivating Entrepreneurship; Institute of International European Affairs: Dublin, Ireland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Halabí, C.E.; Lussier, R.N. A model for predicting small firm performance. J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2014, 21, 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grin, E.J.; Acosta, F.G.; Sarfati, G.; Alves, M.A.; Gomes, M.V.P.; Spink, P.K.; Fernandes, R.J.R. Desenvolvimento de Políticas Públicas de Fomento ao Empreendedorismo em Estados e Municípios; Fundação Getúlio Vargas: São Paulo, Brazil, 2016; 52p, Available online: https://goo.gl/ryXk9A (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Castaño, M.S.; Méndez, M.T.; Galindo, M.Á. The effect of social, cultural, and economics factors on entrepreneurship. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 1496–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audretsch, D.B.; Heger, D.; Veith, T. Infrastructure and entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2015, 44, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Consortium. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. 2015. Available online: https://www.gemconsortium.org/file/open?fileId=49480 (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Maroufkhani, P.; Wagner, R.; Wan Ismail, W.K. Entrepreneurial ecosystems: A systematic review. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2018, 12, 545–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endeavor. Índice de Cidades Empreendedoras 2020. Available online: https://endeavor.org.br/ambiente/ice-2020/ (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Connected Smart Cities. Ranking. Resultados 2017. Available online: http://www.connectedsmartcities.com.br/resultados-do-ranking-connected-smartcities/ (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Hair, J.; Babin, B.; Money, A.; Samouel, P. Fundamentos de Métodos de Pesquisa em Administração; Bookman: Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bardin, L. Análise de Conteúdo; Edições: Lisboa, Portugal, 1977; p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- IBGE. Santa Catarina e Florianópolis; Instituto Brasileiro De Geografia e Estatísticas: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Florianópolis. Revisão Plano Municipal Integrado de Saneamento Básico. 2021. Available online: https://www.pmf.sc.gov.br/arquivos/arquivos/pdf/28_01_2021_14.02.38.2702fa6dabba3692679338f9eac54d38.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Sarquis, A.B.; Fiates, G.G.S.; Hahn, A.K.; Cavalcante, F.R. Empreendedorismo inovador no polo tecnológico de Florianópolis. Rev. Eletrônica Estrateg. Neg. St. Catarina 2014, 7, 228–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban Systems Brasil. Ranking Connected Smart Cities. 2020. Available online: https://ranking.connectedsmartcities.com.br/ (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Sutto, G. Vale do Silício Brasileiro, Florianópolis tem 3% da População e 20% das Startups, em Negócios/Grandes Empresas de InfoMoney. 2019. Available online: https://www.infomoney.com.br/negocios/grandesempresas/noticia/7929302/vale-do-silicio-brasileiro-florianopolis-tem-3-da-populacao-e20-das-startups (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Ács, Z.J.; Szerb, L.; Autio, E. Global Entrepreneurship Index 2015; The Global Entrepreneurship and Development Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; Available online: http://thegedi.org/2015-global-entrepreneurship-index/ (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Carvalho, L.; Viana Noronha, A.; Mantovani, D. Hélice Tripla e Ecossistema Empreendedor: O papel da FAPESP no ecossistema empreendedor do Estado de São Paulo. Rev. Adm. Contab. Econ. Fund. 2016, 7, 84–101. [Google Scholar]

- Florianópolis. Floripa Empreendedora. 2022. Available online: http://www.pmf.sc.gov.br/sites/ef/index.php?cms=floripa+empreendedora&menu=0 (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Floripa Amanhã. Projeto Smart Floripa 2030. 2018. Available online: http://floripamanha.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/relatorio-smart-city-floripa.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Rede De Inovação Florianópolis. Lei Municipal de Estímulos à Inovação é Tema de e-Book Gratuito Lançado pela Rede de Inovação. 2021. Available online: https://redeinovacao.floripa.br/lei-municipal-de-estimulos-a-inovacao-e-tema-de-e-book-gratuito-lancado-pela-rede-de-inovacao/ (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- VIA. Mobilidade em Florianópolis: Em Direção à Ressignificação das Ruas. 2020. Available online: https://via.ufsc.br/mobilidade-florianopolis/ (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Azevedo, C.S.I.; Teixeira, S.C. Florianópolis: Uma Análise Evolutiva do Desenvolvimento Inovador da Cidade a Partir do Seu Ecossistema de Inovação. Braz. J. Account. Manag. 2017, 6, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SC Inova. Por R$ 1,86 bi, RD Station é adquirida pela Totvs. 2021. Available online: https://scinova.com.br/por-r-186-bi-rd-station-e-adquirida-pela-totvs/ (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Ferreira, J.J.M.; Fernandes, C.I.; Kraus, S. Entrepreneurship research: Mapping intellectual structures and research trends. Stud. Appl. Econ. 2019, 13, 181–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]