Study on Ecological Value Co-Creation of Tourism Enterprises in Protected Areas: Scale Development and Test

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Value Co-Creation Theory

2.2. Symbiosis Theory

2.3. Ecological Value Co-Creation

3. Materials and Method

3.1. Method

3.2. Item Genearation

3.3. Theoretical Analysis

- (1)

- Pro-environmental behavior

- (2)

- Dialogue

- (3)

- Knowledge sharing

- (4)

- Co-opetition behavior

- (5)

- Construction of destination reputation

- The overgeneralized and difficult topics are deleted, such as “the sustainable use of natural ecological resources by enterprises” and “the voluntary adoption of environmental management measures by enterprises”.

- The items of tourism enterprises that are not suitable for protected areas are deleted. For example, “the enterprise relies on the overall understanding of the scenic area to obtain professionals”.

- Four out of five scholars suggested that it is necessary to divide general pro-environmental behavior into the environmental activism behavior and environmental citizenship behavior according to Stern (1999).

3.4. Psychometric Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Research Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Duran, A.P. Effectiveness of Protected Areas and Implications for Conservation of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2014, 125, 49–67. Available online: https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/handle/10871/15826 (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Dudley, N. Guidelines for Applying Protected Area Management Categories; Iucn: Gland, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, M.; Müller, M.; Woltering, M.; Arnegger, J.; Job, H. The economic impact of tourism in six German national parks. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2010, 97, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.; Job, H. The economics of protected areas–a European perspective. Z. Wirtsch. 2014, 58, 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Job, H.; Paesler, F. Links between nature-based tourism, protected areas, poverty alleviation and crises—The example of Wasini Island (Kenya). J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2013, 1–2, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spenceley, A.; Schagner, J.P.; Engels, B.; Thomas, C.C.; Engelbauer, M.; Erkkonen, J.; Job, H.; Kajala, L.; Majewski, L.; Metzler, D.; et al. Visitors Count! Guidance for Protected Areas on the Economic Analysis of Visitation; German Federal Agency for Nature Conservation (BfN): Bonn, Germany, 2021.

- Phillips, H.A. Human: Substance, Relationship, Choice, Value and Nature. J. Med. Philos. 2012, 37, 325–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Jin, J.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, L. The change of ecological service value and the promotion mode of ecological function in mountain development using InVEST model. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Pan, J.; Hu, Y. Time and Space Change of Eco-capital Value and Ecology-Economy in Gansu Province. J. Nat. Resour. 2017, 32, 64–75. [Google Scholar]

- Straton, A. A complex systems approach to the value of ecological resources. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 56, 402–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, M.M.; Aldakhil, A.M.; Nassani, A.A.; Azam, M.N. Community-based ecotourism management for sustainable development of marine protected areas in Malaysia. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2017, 136, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennell, D.A. Ecotourism: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 24–32. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, L.; Zhang, X.; Deng, J.; Pierskalla, C. Recreation ecology research in China’s protected areas: Progress and prospect. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2020, 6, 1813635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiraa, A.; Wilmott, I.K. The Takitumu Conservation Area: A community-owned ecotourism enterprise in the Cook Islands. Ind. Environ. 2001, 24, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zanamwe, C.; Gandiwa, E.; Muboko, N.; Kupika, O.L.; Mukamuri, B.B. An analysis of the status of ecotourism and related developments in the zimbabwe’s component of the great limpopo transfrontier conservation area. Sustain. Environ. 2020, 5, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijaya, W.; Damanik, J. Study on Ecotourism Development in Kapota Island Wakatobi Regency, Southeast Sulawesi Province. E-J. Tour. 2020, 7, 300–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brillo, B.B.C. Development of a small lake: Ecotourism enterprise for Pandin lake, San Pablo City, Philippines. Lakes Reserv. Res. Manag. 2016, 21, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, S.; Tribe, J. Exploring the economic sustainability of the small tourism enterprise: A case study of Tobago. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2005, 30, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodenburg, E.E. The effects of scale in economic development: Tourism in Bali. Ann. Tour. Res. 1980, 7, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassin, Y.; Van Rossem, A.; Buelens, M. Small-business owner-managers’ perceptions of business ethics and CSR-related concepts. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 98, 425–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodland, M.; Acott, T. Sustainability and local tourism branding in England’s South Downs. J. Sustain. Tour. 2007, 15, 715–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüzbaşıoğlu, N.; Topsakal, Y.; Çelik, P. Roles of tourism enterprises on destination sustainability: Case of Antalya, Turkey. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 150, 968–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, M.n.; Ge, Q.s. Environmental Behavior of Tourism Enterprises in the World Heritage Sites and Its Driving Mechanism; An Empirical Study on Tourist Hotels in Zhangjiajie. Tour. Trib. Xuekan 2012, 27, 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Kilipiris, F.; Zardava, S. Developing sustainable tourism in a changing environment: Issues for the tourism enterprises (travel agencies and hospitality enterprises). Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 44, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lasso, M.A.H. The Double-edged Sword of Tourism: Tourism Development and Local Livelihoods in Komodo District, East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia. Ph.D. Thesis, Griffith University, Queensland, Austrilia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Izurieta, G.; Torres, A.; Patino, J.; Vasco, C.; Vasseur, L.; Reyes, H.; Torres, B. Exploring community and key stakeholders’ perception of scientific tourism as a strategy to achieve SDGs in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 39, 100830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altinay, L.; Sigala, M.; Waligo, V. Social value creation through tourism enterprise. Tour. Manag. 2016, 54, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quyet, L.; Duy, P.; Toan, V. Sustainable development of tourism economy in Phu Quoc Island, Kien Giang Province, Vietnam: Current situation and prospects. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2022; Volume 1028, p. 012005. [Google Scholar]

- Tervo-Kankare, K. Entrepreneurship in nature-based tourism under a changing climate. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 1380–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambrano-Monserrate, M.A.; Silva-Zambrano, C.A.; Ruano, M.A. The economic value of natural protected areas in Ecuador: A case of Villamil Beach National Recreation Area. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2018, 157, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Val Simardi Beraldo Souza, T.; Thapa, B.; Rodrigues, C.G.d.O.; Imori, D. Economic impacts of tourism in protected areas of Brazil. J. Sustain. Tour. 2019, 27, 735–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaodirelwe, I.; Masunga, G.S.; Motsholapheko, M.R. Community-based natural resource management: A promising strategy for reducing subsistence poaching around protected areas, northern Botswana. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 2269–2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bary, A. Die Erscheinung der Symbiose: Vortrag Gehalten auf der Versammlung Deutscher Naturforscher und Aerzte zu Cassel; Trübner: Strasbourg, France, 1879. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, G.D. Plant symbiosis. Edward Arnold 1969, 15–16. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/jobm.19700100821 (accessed on 15 December 2021).

- Margulis, L. Symbiosis in evolution: Origins of cell motility. In Evolution of Life; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991; pp. 305–324. [Google Scholar]

- Chertow, M.R. Industrial symbiosis: Literature and taxonomy. Annu. Rev. Energy Environ. 2000, 25, 313–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chertow, M.R. “Uncovering” industrial symbiosis. J. Ind. Ecol. 2007, 11, 11–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Yu, C.; Zhou, Y. Consensus, symbiosis and a win-win situation: The process model of value co-creation. Sci. Res. Manag. 2015, 36, 129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, E. Symbiosis and consensus as integrative factors in small groups. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1956, 21, 174–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, J.P.; Vaidyanathan, B. Substitution or symbiosis? Assessing the relationship between religious and secular giving. Soc. Forces 2011, 90, 157–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Long, B. Symbiosis of Mining Heritage and Community: A Case Study of Zhongfu Mining Heritage in Jiaozuo. J. Landsc. Res. 2020, 12, 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- Lessard, J.M.; Habert, G.; Tagnit-Hamou, A.; Amor, B. A time-series material-product chain model extended to a multiregional industrial symbiosis: The case of material circularity in the cement sector. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 179, 106872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijon, N.; Wassenaar, T.; Junqua, G.; Dechesne, M. Towards a sustainable bioeconomy through industrial symbiosis: Current situation and perspectives. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, A.F.; Storbacka, K.; Frow, P. Managing the co-creation of value. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. It’s all B2B… and beyond: Toward a systems perspective of the market. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2011, 40, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zomerdijk, L.G.; Voss, C.A. Service design for experience-centric services. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabiddu, F.; Lui, T.W.; Piccoli, G. Managing value co-creation in the tourism industry. Ann. Tour. Res. 2013, 42, 86–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, R. Examining the mechanism of the value co-creation with customers. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 116, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normann, R.; Ramirez, R. Designing Interactive Strategy: From Value Chain to Value Constellation; University of Oxford: Oxford, UK, 1998; pp. 1620–1630. [Google Scholar]

- Vargo, S.L.; Lusch, R.F. Service-dominant logic: Continuing the evolution. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-creation experiences: The next practice in value creation. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prahalad, C.K.; Ramaswamy, V. Co-opting customer competence. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2000, 78, 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan, K.R.; Read, S. Value co-creation: Concept and measurement. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 290–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Gong, T. Customer value co-creation behavior: Scale development and validation. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1279–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Vazquez, M.; Revilla-Camacho, M.Á.; Cossío-Silva, F.J. The value co-creation process as a determinant of customer satisfaction. Manag. Decis. 2013, 51, 1945–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsström, B. Value Co-Creation in Industrial Buyer-Seller Partnerships-Creating and Exploiting Interdependencies: An Empirical Case Study; Åbo Akademi University Press: Turku, Finland, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Saarijärvi, H.; Kannan, P.; Kuusela, H. Value co-creation: Theoretical approaches and practical implications. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2013, 25, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswamy, V.; Gouillart, F. Building the co-creative enterprise. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2010, 88, 100–109. [Google Scholar]

- Nenonen, S.; Storbacka, K. Business model design: Conceptualizing networked value co-creation. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2010, 2, 43–59. [Google Scholar]

- Storbacka, K.; Frow, P.; Nenonen, S.; Payne, A. Designing business models for value co-creation. In Special Issue—Toward a Better Understanding of the Role of Value in Markets and Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2012; Volume 9, pp. 51–78. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Hong, X.U. A Study on Value Co-creation of the Core Subjects of the Exhibition under the Grounded Theory. Tour. Forum 2017, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.; Liu, W.; Gao, J. Value Co-Creation Mechanism of Logistics Service Supply Chain under Service-Dominant Logic. China Bus. Mark. 2014, 28, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Balampanidis, I.; Vlastaris, I.; Xezonakis, G.; Karagkiozoglou, M. ‘Bridges Over Troubled Waters’? The Competitive Symbiosis of Social Democracy and Radical Left in Crisis-Ridden Southern Europe. Gov. Oppos. 2021, 56, 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razdorskaya, O. Reflection and creativity: The need for symbiosis. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 209, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntasiou, M.; Andreou, E. The standard of industrial symbiosis. Environmental criteria and methodology on the establishment and operation of industrial and business parks. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2017, 38, 744–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Dong, M.; Zhang, L.; Luan, X.; Cui, X.; Cui, Z. Comprehensive evaluation of environmental and economic benefits of industrial symbiosis in industrial parks. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 354, 131635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budowski, G. Tourism and environmental conservation: Conflict, coexistence, or symbiosis? Environ. Conserv. 1976, 3, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Huang, J.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, D.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, X.; Chen, M. Evaluating the symbiosis status of tourist towns: The case of Guizhou Province, China. Ann. Tour. Res. 2018, 72, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, R.N.; Baum, T.; Golubovskaya, M.; Solnet, D.J.; Callan, V. Applying endosymbiosis theory: Tourism and its young workers. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 78, 102751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, G. Four corners of human ecology: Different paradigms of human relationships with the earth. In Nature and the Human Spirit: Toward an Expanded Land Management Ethic; Venture: State College, PA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura, H. A framework for a possible symbiosis between man and nature: Historical changes in the concepts of nature, science, and technology. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sport. 2015, 45, 374–379. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Qu, H.; Huang, D.; Chen, G.; Yue, X.; Zhao, X.; Liang, Z. The role of social capital in encouraging residents’ pro-environmental behaviors in community-based ecotourism. Tour. Manag. 2014, 41, 190–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.L. Balancing people and park: Towards a symbiotic relationship between Cape Town and Table Mountain National Park. Curr. Issues Tour. 2011, 14, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fennell, D.A.; Weaver, D.B. Vacation farms and ecotourism in Saskatchewan, Canada. J. Rural. Stud. 1997, 13, 467–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B. Eco-value and Practice in Ecology. Socialist 2013, 13, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Nation, U. Global Assessment Reports. 2005. Available online: https://www.docin.com/p-724721856.html. (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Donhauser, J. Making ecological values make sense: Toward more operationalizable ecological legislation. Ethics Environ. 2016, 21, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. Viewing the structure relationship among ecotourism stakeholders from the perspective of Systematology. Tour. Trib. 2010, 5, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Devani, K.; Quinton, C.D.; Archer, J.A.; Santos, B.F.; Martin-Collado, D.; Amer, P.; Pajor, E.A.; Orsel, K.; Crowley, J.J. Estimation of economic value for efficiency and animal health and welfare traits, teat and udder structure, in Canadian Angus cattle. J. Anim. Breed. Genet. 2021, 138, 314–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldeyohannes, A.; Cotter, M.; Biru, W.D.; Kelboro, G. Assessing changes in ecosystem service values over 1985–2050 in response to land use and land cover dynamics in Abaya-Chamo Basin, Southern Ethiopia. Land 2020, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joppa, L.N.; Loarie, S.R.; Pimm, S.L. On the protection of “protected areas”. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 6673–6678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Ochuodho, T.O.; Yang, J. Impact of land use and climate change on water-related ecosystem services in Kentucky, USA. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 102, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barco, A.; Borin, M. Treatment performances of floating wetlands: A decade of studies in North Italy. Ecol. Eng. 2020, 158, 106016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCool, S.F. Constructing partnerships for protected area tourism planning in an era of change and messiness. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, T.; Stronza, A. Collaboration theory and tourism practice in protected areas: Stakeholders, structuring and sustainability. J. Sustain. Tour. 2009, 17, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Q.; Yaseen, M.R.; Anwar, S.; Makhdum, M.S.A.; Khan, M.T.I. The impact of tourism, renewable energy, and economic growth on ecological footprint and natural resources: A panel data analysis. Resour. Policy 2021, 17, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, Z.; Zou, X.; Zuo, P.; Song, Q.; Wang, C.; Wang, J. Impact of landscape patterns on ecological vulnerability and ecosystem service values: An empirical analysis of Yancheng Nature Reserve in China. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 72, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyck, B.; Silvestre, B.S. Enhancing socio-ecological value creation through sustainable innovation 2.0: Moving away from maximizing financial value capture. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 1593–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A.J.; Badiane, K.K.; Haigh, N. Hybrid organizations as agents of positive social change: Bridging the for-profit and non-profit divide. In Using a Positive Lens to Explore Social Change and Organizations; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 152–174. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, S.; Silvestre, B.S. Managing stakeholder relations when developing sustainable business models: The case of the Brazilian energy sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 45, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, G.A., Jr. A paradigm for developing better measures of marketing constructs. J. Mark. Res. 1979, 16, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgado, F.F.; Meireles, J.F.; Neves, C.M.; Amaral, A.; Ferreira, M.E. Scale development: Ten main limitations and recommendations to improve future research practices. Psicol. Reflexão e Crítica 2017, 30, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forestry, N.; Administration, G. National Forestry and Grassland Administration Government Website, Guangdong Has Built 380 Nature Reserves, the Largest Number in China. Available online: http://www.forestry.gov.cn/main/72/20180726/165730797143205.html2018. (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Bureau, D. All about Dinghu. 2021. Available online: http://www.dhs.scib.cas.cn/sy_tsjj/ (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Shaoguan Mount Danxia Management Committee. 2020. Available online: http://dxs.sg.gov.cn/homepage/index.html (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Caulley, D.N. Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences. Qual. Res. J. 2007, 6, 227. [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Sebasto, N.J.; D’Costa, A. Designing a Likert-type scale to predict environmentally responsible behavior in undergraduate students: A multistep process. J. Environ. Educ. 1995, 27, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, T.M.; Wu, C.H.; Huang, L.M. The influence of place attachment on the relationship between destination attractiveness and environmentally responsible behavior for island tourism in Penghu, Taiwan. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 1166–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Smith, L.D.G.; Weiler, B. Relationships between place attachment, place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviour in an Australian national park. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 434–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, K.; Packer, J.; Ballantyne, R. Using post-visit action resources to support family conservation learning following a wildlife tourism experience. Environ. Educ. Res. 2011, 17, 307–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. A Study on the Inflfluence Mechanism of Tourists’ Pro-Environment Behavior in Different Spatio-Temporal Contexts: From the Perspective of Deindividuation. Ph.D. Thesis, Sun-Yat Sen University, Guangzhou, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ngo, L.V.; O’Cass, A. Creating value offerings via operant resource-based capabilities. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2009, 38, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Zhang, W.; Liu, J. Scale Development and Test of E-Travel Service Providers’ Customer Need Knowledge. Tour. Sci. 2015, 29, 14–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, J.; Xu, J.; Liang, X. Development of inter-enterprise value co-creation scale based on DART model. Jinan J. Philos. Soc. Sci. 2014, 36, 93–102. [Google Scholar]

- Hoopes, D.G.; Postrel, S. Shared knowledge, “glitches”, and product development performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 1999, 20, 837–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskell, P.; Malmberg, A. Localised learning and industrial competitiveness. Camb. J. Econ. 1999, 23, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maglio, P.P.; Spohrer, J. Fundamentals of service science. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, S. Research on Competitive Advantage of Cluster Enterprises Based on Shared Resource View. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bouncken, R.B.; Gast, J.; Kraus, S.; Bogers, M. Coopetition: A systematic review, synthesis, and future research directions. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2015, 9, 577–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalebuff, B.J.; Brandenburger, A.; Maulana, A. Co-Opetition; Curreney Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gnyawali, D.R.; Park, B.j. Co-opetition and technological innovation in small and medium-sized enterprises: A multilevel conceptual model. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2009, 47, 308–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, M.; Raza-Ullah, T. A systematic review of research on coopetition: Toward a multilevel understanding. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 57, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, A.S.; Le Roy, F.; Gnyawali, D.R. Sources and management of tension in co-opetition case evidence from telecommunications satellites manufacturing in Europe. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2014, 43, 222–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padula, G.; Dagnino, G.B. Untangling the rise of coopetition: The intrusion of competition in a cooperative game structure. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 2007, 37, 32–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. The Mediating Effect of Organizational Learning on Competitive and Cooperative Behavior and Innovation Performance of Firms in Industrial Clusters. Master’s Thesis, Dongbei University of Finance and Economics, Dalian, China, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Spender, J. The geographies of strategic competence: Borrowing from social and educational psychology to sketch an activity and knowledge-based theory of the firm. In The Role of Technology, Strategy, Organization and Regions; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 417–439. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Dubinsky, A.J. A conceptual model of perceived customer value in e-commerce: A preliminary investigation. Psychol. Mark. 2003, 20, 323–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBlanc, G.; Nguyen, N. Cues used by customers evaluating corporate image in service firms: An empirical study in financial institutions. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1996, 7, 44–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; Kastenholz, E. Corporate reputation, satisfaction, delight, and loyalty towards rural lodging units in Portugal. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2011, 30, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, K.T. Building Reputational Capital: Strategies for Integrity and Fair Play that Improve the Bottom Line; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2004; pp. 86–98. [Google Scholar]

- Christou, E. Tourist destinations as brands: The impact of destination image and reputation on visitor loyalty. In Productivity in Tourism: Fundamentals and Concepts for Achieving Growth and Competitiveness; Keller, P., Bieger, T., Eds.; Erich Schmidt Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Artigas, E.M.; Vilches-Montero, S.; Yrigoyen, C.C. Antecedents of tourism destination reputation: The mediating role of familiarity. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2015, 26, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, R. The strategic analysis of intangible resources. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 1992, 13, 135–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, P.W.; Dowling, G.R. Corporate reputation and sustained superior financial performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2002, 23, 1077–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, T.D.; Deephouse, D.L.; Ferguson, W.L. Do strategic groups differ in reputation? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1195–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Xiong, S.; Yang, D. An empirical analysis of the impact of shared resources on enterprise competitive advantage in logistics cluster. Stat. Decis. 2015, 24, 196–199. [Google Scholar]

- Clark-Carter, D. Doing Quantitative Psychological Research: From Design to Report; Psychology Press/Erlbaum (UK) Taylor & Francis: Hove, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming; Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Tull, D.S. Marketing Research: Measurement and Method, 6th ed.; Macmillan Publisher: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnskov, C. How does social trust affect economic growth? South. Econ. J. 2012, 78, 1346–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusch, R.F.; Brown, J.R. Interdependency, contracting, and relational behavior in marketing channels. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Interviewees | Affiliated Enterprises | Nature of Enterprises | Position of the Interviewees |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Mr. Zhong | Dinghu Mountain Management Committee | Management committee | Director |

| A2 | Mr. Tang | Yuntianhai Forest Resort | State-owned enterprise | Deputy General Manager |

| A3 | Mr. Wen | Dinghu Mountain Resort | Private enterprise | General Manager |

| A4 | Mr. Lee | Yuandian Art Guest House | Private enterprise | Owner |

| A5 | Mr. Guo | Fenyangju Hotel | Private enterprise | Owner |

| A6 | Mr. Gan | Zhuzhuang Hotel | Private enterprise | Director |

| A7 | Mr. Long | Fulaige Hotel | Private enterprise | Director |

| B1 | Ms. Chen | Danxia Mountain Management Committee | Management committee | Deputy Director |

| B2 | Mr. Yu | Danxia Mountain Nature School | Non-profit organization | Director |

| B3 | Mr. Zhang | Danxia Mountain Cable-car company | Joint venture enterprise | General Manager |

| B4 | Mr. Jiang | Danxia Curise Line company | Private enterprise | Deputy General Manager |

| B5 | Ms. Liu | Yuanse Guest House | Private enterprise | General Manager |

| B6 | Mr. Mei | Yanzi Ninan B&B | Individual household | Director |

| B7 | Mr. Mu | Danxia Mountain International Youth Hostel | Individual household | Owner |

| Main Category | Subcategory | Frequency | Representative Interview Statements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pro-environmental behavior | Understanding environmental information | 3 | B3 Management committee sends us information on nature conservation or asks us to participate in important activities to raise awareness and consciousness of the conservation of the landscape sometimes. |

| Compliance with environmental regulations | 4 | A2 There is no process and no formalities, to cut trees to build lodging is illegal, it requires applying for filing. After the planning assessment confirms that it does not affect the overall ecological environment, it can be completed. It definitely needs to be assessed by experts and is not that arbitrary. It really is illegal to cut down at will. | |

| Energy conservation | 3 | A2 We will Use some low-energy devices, TVs and lights are going according to this requirement. Not cutting down trees at random is also a form of energy saving. | |

| Use of environmentally friendly materials | 3 | A6 We have a dedicated cutlery cleaning plant here and the cutlery is delivered centrally, we do not use disposable cutlery. | |

| Disposal of waste materials | 7 | A7 There are strict requirements from the management committee regarding ecological protection. Because Nankun mountain is mainly about ecology, there are strict controls on the discharge of sewage. There is a special drainage ditch for waste water, which will be discharged to a sewage treatment system below, so that the waste water can meet the discharge standard before being discharged. | |

| Participation in environmental volunteering activities | 3 | A7 We focus on developing environmental awareness on our side. For example, we go to the top of Nankun mountain to pick up rubbish, or we organize street cleaning when the holidays are approaching. | |

| Dissemination of environmental information | 1 | A2 In terms of environmental education for staff, systems are used to regulate human behavior. Thoughtful education is present in every training session: the stick and the carrot. | |

| Alerting or resisting environmentally damaging behavior | 1 | A7 If I find that a business or a visitor is damaging the environment, I will go and remind them. We will also have many signs in the scenic area to remind visitors to take care of the ecological environment. | |

| Paying extra costs to restore the ecosystem | 3 | B4 The burden of expense of replacing all boats that use oil with electric boats is certainly a burden at first. However in the long run, it is all a trend. A small burden is also needed for the time being, in terms of sustainability. The costing we can work out. | |

| Dialogue | Exchange of product and service information | 7 | B2 Our nature school also takes the initiative to reach out to those guest houses in the neighborhood that do excursions. We play openly with them, it is not that I just maintain my part of the customer base, we are open and welcome them to come in together as well. |

| Good and open communication | 5 | A7 Communication with the management committee is generally smooth and any problems are resolved well, as everyone is local and there is generally no confusing communication. | |

| Use of dialogue to resolve differences of opinion | 3 | A2 The format of the symposium is an open topic; brainstorming is not minding what you say, take it if it works, filter it if it does not; these are all things that can be brought up to each other, difficulties, complaints, whatever. We will also make suggestions, which are very common. Because we have our own difficulties, but through communication with the management committee, mutual coordination and mutual understanding, we can solve problems. | |

| Establishment of channels for information sharing | 5 | A6 The management committee has a WeChat platform. There are also two groups we have, one for large enterprises and one for farmhouses. In the WeChat group, there will be the Boxiang Hotel, Shizishui and so on, which are relatively large hotels. There are about 20 enterprises in them, and there will also be village cadres such as the village committee and the secretary, including the Xiaping and Shangping villages. | |

| Knowledge sharing | Exchange and discussion on ecological product services | 6 | A7 We also have some exchanges between local villagers. For example, if a guest wants to eat this dish that we do not have in our house, they will go to the restaurant next door that has this dish and order it. |

| Access to new knowledge of ecological products services | 4 | B6 We attend sharing sessions organized by the management committee sometimes in that geological museum about science and popularization. | |

| Learning to follow up on innovation in ecological products services | 4 | A6 People in the restaurant business around would imitate us. For example, some of the decorations in our restaurant are made of bamboo. So, when other people saw it, they made it out of bamboo too; others copied our menu. The roast chicken used to be roasted manually, but then I added a motor to roast it electrically, so others copied that, too. | |

| Voluntary sharing of experience and knowledge | 5 | A3 If the management committee invites our hotel to do some experience-sharing activities, it is not only an exchange process between the enterprises but also a promotion for ourselves; why not? | |

| Co-creation behavior | Improvement of the competitiveness through the competitors | 9 | A4 Nankun mountain is welcoming to outside businesses and I also hope that there will be more shops like mine in this town so that an industry can be formed, or at least an atmosphere can be created, which will drive the clientele. Every change of hands brings in something new from outside, so it keeps the whole tourist area alive and shining. |

| Mutual referrals | 2 | A2 Resources sharing, for some guests, we cannot meet their requirements, we do not have a spa, but we can recommend them to Shizishui. We recommend each other; they also push to us. We will also have contact with some of the owners of the farmhouse. Some guests said, there is no recommendation of some shops, we will also have a recommendation. These are resources. | |

| Cooperation in the development of ecological products and services | 3 | B2 Guest House B&B can provide food and accommodation as well as being a guest house in itself; they can easily work it out and can do very well. We will also give them the requirement for a life class course. That is definitely their strong point. But they don’t have the manpower to do this outdoors either, and the course activities would require us to go and execute it for them. They are not professional, either. So I should say it’s each doing their own area, but we just combine to do it together. | |

| Enhancing competitiveness through cooperation | 3 | B5 The rural tour is a combination of all the local resources, and we are the ones who work most closely with Danxia mountain, the villages and the cruise enterprises. We have basically formed a system and have been doing these courses and activities for a long time, we are used to doing them. At Danxia mountain, it is just doing what belongs inside Danxia mountain. The villagers outside just do what is outside, its their own experiential projects such as digging sweet potatoes, cutting rice and catching chickens. But it also seems that we are the only ones who do a course that blends Danxia mountain with the villagers and art for a few days in a row. | |

| Building a mutually beneficial partnership | 3 | A2 Since we have this shared resource, we all have different environments, the same competition, but with differences. It’s all neighbourhood enterprises and we need to maintain a good collaborative approach. As long as there are people we have a way to do business. Our main idea is to be unified, we want to attract people from outside. Apart from us doing it, other people do it too, how do you bring others up to compete, share resources, complement each other, improve the package and form a win–win situation. | |

| Collective reputation | Creation of a regional trademark or brand identity | 4 | A1 “Nankun mountain” is a trademark that I registered more than ten years ago. At present, the following enterprises in Yong Han Town, such as “Fuli Nankun Mountain” and “Biguiyuan Nankun Mountain Spa” are infringing. |

| Dependence on scenic spots for customer resources | 2 | A6 Some of our guests come to our house specifically for dinner after being introduced to us by friends, but this is less frequent, or they come to Nankun mountain and then drop by our house for a meal more often. | |

| Reliance on scenic spots for talent | 2 | B1 It is a little bit more remote in the mountains, but because there are so many interesting inns, so many young people, all kinds of new forces coming in. They don’t feel like a closed place, either. It feels like an open mountain, it’s not the kind of place you see in other reserves, it’s not the kind of place that’s cold and quiet, it’s very vibrant. | |

| Binding ecological damage, bad product service practices | 1 | A7 If there are enterprises in the scenic area with shoddy products or bad service practices, it will have an impact on the whole area. There will be strict controls on the management committee side. | |

| Help of scenic areas to build and maintain a good image as a tourist destination | 2 | A2 We are all about serving our guests, the whole Nankun mountain is a brand. If the guests see that the village is dirty and the villagers are brutal, there will be no more guests in the future. We are being a model, an example, regulating our own behavior first, ourselves before others. We have to set a good example for ourselves so that they can learn and see that this is how big enterprises do things, this is how they have rules and regulations. We have to set an example to them, and that’s all we can do. | |

| Leading the way in scenic awareness | 2 | A2 According to my point of view, it turns out that this is a mountain and a village. If there is no big enterprise to drive it, it will not work any more. After all, small enterprises are small-scale. The premise is definitely to have a big enterprise to drive the economy, the flow of people and visitors. |

| Core Concepts/Variables | Scale | Object | Author |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Environmental responsibility behavior | General conduct: -To solve the environmental problems. -To read reports or books related to the environment. -To discuss with others issues related to the environmental protection. -To convince my companions to protect the natural environment. Specific acts: -To report environment damage behaviors to authorities. -Observance of laws about environmental protection. -To pick litter on the beach. -To attend clean-up on the beach. |

Visitors to the Penghu Islands |

Cheng et al. (2013) [99] |

|

Pro-environmental behavior | Low involvement: -To reduce my visits to the national park if one of my favorite attractions needed to be restored. -To stop visiting the national park if one of my favorite attractions needed to be restored. -To tell my friends not to feed the animals in the national park. -To sign the petition to protect this national park. -Learned about the natural environment of the national park. -To pay the extra entry fee for the national park project. High involvement: -To invest time in national park protection projects. -To attend national park public meetings. -To write in support of this national park. |

Visitors in the national park |

Ramkissoon et al. (2013) [100] |

| Pro-environmental behavior | -To use energy sparingly. -To recycle household waste. -To sort the garbage. -To use recycle bags for shopping. -To use public transport. -To remind people to protect environment. -To learn about environmental issues. -To make donations to support environmental projects. -To participate in voluntary activities in environmental protection. |

The individual in a life situation | Wu (2017) [102] |

| Core Concepts/Variables | Scale | Object | Author |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dialogue |

-To exchange information with the downstream enterprise. -To communicate with the downstream enterprise as much as possible. -Communication with the downstream enterprise is open and good. -To use dialogue to resolve any disagreements with the downstream enterprise. | Upstream enterprises in value co-creation with downstream enterprises | Xie (2013), Ren et al. (2014) [104,105] |

| Interaction | -To easily express my specific requirements throughout the process. -Enterprises communicate process-related information to consumers. -To provide adequate customer interactions. -To take an active role in the interaction. | Consumers who engage in value co-creation with enterprises | Ranjan and Read (2016) [53] |

| Core Concepts/Variables | Scale | Object | Author |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Collective learning and knowledge sharing network | -To transfer knowledge between enterprises in your industry on a regular basis. -Technical and managerial staff often interact with other enterprises in a personal way. -To imitate or follow the product and process innovations made by other enterprises in the same industry. -To capture the benefits of technological innovation spillovers from other enterprises in the same industry. -To acquire new production and management knowledge from other enterprises or organizations. |

Manufacturing cluster enterprises |

Geng, 2005 [109] |

| Knowledge sharing | -Welcoming my comments and suggestions on existing products as well as the development of new products. -Providing me with full explanations and information. -To give my time to comment on their products and work flow. -To provide the right environment and opportunity for me to make comments and suggestions. |

Consumers who engage in value co-creation with enterprises |

Ranjan and Read (2016) [53] |

| Core Concepts /Variables | Scale | Object | Author |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Co-opetition behavior | With suppliers: -To improve its responsiveness to the market. -Stable cooperation will help the enterprise to build a good image in the market. -Regular exchanges of information with the supplier. -To own a decisive say in the quality of the supplier’s products. -Mutually beneficial relationship between enterprise and suppliers. -To have multiple suppliers competing against each other. -Regular communication between the senior management of the enterprise and the supplier. With the buyer’s enterprises: -The customer always provides good advice to the enterprise. -To be sensitive to changes in market demand from the customers. -To cooperate with the customer in the production, research and development, human resources, etc. -Exchanges of information between the enterprise and the customers in terms of knowledge and skills. -Relative to enterprise, the customers are in a strong negotiating position. -The customer always demands a higher quality product or service. With the same industry: -The enterprise is our main competitor. -Competing with this enterprise can significantly improve our operational efficiency. -To learn knowledge and skills from the business. With complementary producers: -Has formed a good communication and cooperation relationship with our enterprise. -To help to enhance the market image of our products. -To help to improve the overall quality of our products with our customers. -The development of the market requires a joint effort from both of us. |

Cluster enterprises in high-tech parks | Li (2012) [116] |

|

Co-opetition interaction | -Has developed a strong desire to collaborate with competitors. -Would be better served by working with related enterprises with which you have a competitive relationship. -Always gains more from working with competitors. -Competitor’s advertising campaign will also help to increase sales of your products. |

Manufacturing cluster enterprises | Hoopes et al., 1999, Maskell et al., 1999, and Spender et al., 1998 [106,107,117] |

| Core Concepts/Variables | Scale | Object | Author |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Collective reputation | -Be able to guess what industry you are in by saying where you are located. -Regional trademark or brand identity is unique. -Region’s overall perception by the outside world will be of great help to the enterprise in gaining access to customers. -Any of the region’s businesses are to commit forgery, the reputation of the whole region would be seriously affected. |

Manufacturing cluster enterprises |

Hall (1992), Roberts et al. (2002) and Ferguson et al. (2000) [124,125,126] |

| Shared reputation | -External perception can help enterprises gain access to customer resources. -The reputation of the whole park will be seriously affected if any enterprise here causes troubles. -Overall image helps enterprises to acquire professional talents. -The overall product information helps enterprises to sell the product. | Logistics cluster enterprises | Du et al. (2015) [127] |

| No. | Title Item | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Our enterprise is actively informed about ecological and environmental protection. | Cheng et al. (2013) [99] |

| 2 | Our enterprise complies with the laws and regulations on ecological and environmental protection. | Cheng et al. (2013) [99] |

| 3 | Our enterprise uses energy sparingly in the provision of its products and services. | Interview |

| 4 | Our enterprise uses environmentally friendly materials in the provision of our products and services. | Interview |

| 5 | Our enterprise disposes of waste materials generated from its operations and management. | Interview |

| 6 | Our enterprise actively participates in voluntary activities in the area of ecological protection. | Wu (2017) [102] |

| 7 | Our enterprise promotes or popularizes information on ecological and environmental protection. | Interview |

| 8 | Our enterprise alerts or resists ecological damage. | Cheng et al. (2013) [99] |

| 9 | Our enterprise voluntarily pays additional costs to restore and compensate for damage to the ecological environment. | Ramkissoon et al. (2013) [100] |

| 10 | Our enterprise exchanges information frequently with other businesses or organizations. | Xie (2013) [104] |

| 11 | Our enterprise communicates openly and well with other enterprises or institutions. | Xie (2013) [104] |

| 12 | Dialogue is used to resolve differences of opinion between the enterprise and other enterprises or organizations. | Interview |

| 13 | Our enterprise establishes shared information-sharing channels with other enterprises or organizations. | Interview |

| 14 | Our enterprise regularly interacts with other enterprises or organizations to discuss professional issues related to product services. | Geng (2005) [109] |

| 15 | Our enterprise often acquires new knowledge about products and services from other enterprises or organizations. | Interview |

| 16 | Our enterprise learns and follows up on other enterprises’ or organizations’ innovations in ecological products and services. | Geng (2005) [109] |

| 17 | Our enterprise voluntarily shares its experience and knowledge related to its products and services with other enterprises or organizations. | Ranjan and Read (2016) [53] |

| 18 | Our enterprise has been stimulated by other tourism-related businesses to work harder to improve its competitiveness. | Li (2012) [116] |

| 19 | Our enterprise has a history of referring customers to other tourism-related enterprises. | Interview |

| 20 | Our enterprise has a history of collaborating with other tourism-related enterprises to develop products and services. | Interview |

| 21 | Our enterprise is better developed through cooperation with other tourism-related enterprises. | Li (2012) [116] |

| 22 | Our enterprise cooperates with other tourism-related enterprises for mutual benefit. | Li (2012) [116] |

| 23 | Our enterprise has helped to create a distinctive ecological tourism brand identity for the area. | Interview |

| 24 | Our enterprise helps scenic areas to build and maintain a good image of the place to visit. | Interview |

| 25 | Our enterprise helps to raise the profile of the scenic area. | Interview |

| 26 | Our enterprise relies on external perceptions of the landscape as a whole to access customer resources. | Geng (2005) [109] |

| 27 | Our enterprise is bound to regulate its own behavior in order to maintain the reputation of the scenic area. | Interview |

| Indicators | Category | Number | Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample source | Shenzhen Dapeng | 72 | 36.9% |

| Huizhou Luofu Mountain | 47 | 24.1% | |

| Conghua Hot Spring | 23 | 11.8% | |

| Zhaoqing Dinghu Mountain | 23 | 11.8% | |

| Zhaoqing Xinghu National Wetland Park | 19 | 9.7% | |

| Other (online) | 11 | 5.6% | |

| Main business | Accommodation | 137 | 70.3% |

| Food and Beverage | 19 | 9.7% | |

| Retail | 19 | 9.7% | |

| Travel Agents | 2 | 1.0% | |

| Other | 18 | 9.2% |

| KMO | 0.894 | |

|---|---|---|

| Bartlett’s test | Approximate cardinality | 3049.154 |

| df | 351 | |

| Sig. | 0.000 |

| Questions | Environmental Activism Behavior | Environmental Citizenship Behavior | Dialogue Communication Behavior | Knowledge Sharing Behavior | Co-Opetition Behavior | Destination Reputation Building Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Our enterprise is actively informed about ecological and environmental protection. | 0.611 | |||||

| 2. Our enterprise complies with the laws and regulations on ecological and environmental protection. | 0.692 | |||||

| 3. Our enterprise uses energy sparingly in the provision of its products and services. | 0.803 | |||||

| 4. Our enterprise uses envirommentally friendly materials in the provision of our products and services. | 0.681 | |||||

| 5. Our enterprise disposes of waste materials generated from its operations and management. | 0.593 | |||||

| 6. Our enterprise actively participates in voluntary activities in the area of ecological protection. | 0.706 | |||||

| 7. Our enterprise promotes or popularizes information on ecological and environmental protection. | 0.669 | |||||

| 8. Our enterprise alerts or resists ecological damage. | 0.651 | |||||

| 9. Our enterprise voluntarily pays additional costs to restore and compensate for damage to the ecological environment. | 0.701 | |||||

| 10. Our enterprise exchanges information frequently with other businesses or organizations. | 0.695 | |||||

| 11. Our enterprise communicates openly and well with other enterprises or institutions. | 0.689 | |||||

| 12. Dialogue is used to resolve differences of opinion between the enterprise and other enterprises or organizations. | 0.616 | |||||

| 13. Our enterprise establishes shared information-sharing chanunels with other enterprises or organizations. | 0.616 | |||||

| 14. Our enterprise regularly interacts with other enterprises or organizations to discuss professional issues related to product services. | 0.776 | |||||

| 15. Our enterprise often acquires new knowledge about products and services from other enterprises or organizations. | 0.768 | |||||

| 16. Our enterprise learns and follows up on other enterprises’ or organizations’ innovations in ecological products and services. | 0.745 | |||||

| 17. Our enterprise voluntarily shares its experience and knowledge related to its products and services with other enterprises or organizations. | ||||||

| 18. Our enterprise has been stimulated by other tourism-related businesses to work harder to improve its competitiveness. | ||||||

| 19. Our enterprise has a history of referring customers to other tourism-related enterprises. | 0.563 | |||||

| 20. Our enterprise has a history of collaborating with other tourism-related enterprises to develop products and services. | 0.759 | |||||

| 21. Our enterprise is better developed through cooperation with other tourism-related enterprises. | 0.770 | |||||

| 22. Our enterprise cooperates with other tourism-related enterprises for mutual benefit. | 0.790 | |||||

| 23. Our enterprise has helped to create a distinctive ecological tourism brand identity for the area. | 0.694 | |||||

| 24. Our enterprise helps scenic areas to build and maintain a good image of the place to visit. | 0.742 | |||||

| 25. Our enterprise helps to raise the profile of the scenic area. | 0.707 | |||||

| 26. Our enterprise relies on external perceptions of the landscape as a whole to access customer resources. | 0.697 | |||||

| 27. Our enterprise is bound to regulate its own behavior in order to maintain the reputation of the scenic area. | 0.712 |

| Corrected Item Total Correlation | Cronbach’s Value for the Deleted Item | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Our enterprise is actively informed about ecological and environmental protection. | 0.523 | 0.800 | 0.811 |

| 2. Our enterprise complies with the laws and regulations on ecological and environmental protection. | 0.557 | 0.791 | |

| 3. Our enterprise uses energy sparingly in the provision of its products and services. | 0.694 | 0.745 | |

| 4. Our enterprise uses environmentally friendly materials in the provision of our products and services. | 0.631 | 0.765 | |

| 5. Our enterprise disposes of waste materials generated from its operations and management. | 0.618 | 0.769 | |

| 6. Our enterprise actively participates in voluntary activities in the area of ecological protection. | 0.502 | 0.764 | 0.777 |

| 7. Our enterprise promotes or popularizes information on ecological and environmental protection. | 0.653 | 0.684 | |

| 8. Our enterprise alerts or resists ecological damage. | 0.587 | 0.730 | |

| 9. Our enterprise voluntarily pays additional costs to restore and compensate for damage to the ecological environment. | 0.613 | 0.709 | |

| 10. Our enterprise exchanges information frequently with other businesses or organizations. | 0.741 | 0.762 | 0.846 |

| 11. Our enterprise communicates openly and well with other enterprises or institutions. | 0.740 | 0.759 | |

| 12. Dialogue is used to resolve differences of opinion between the enterprise and other enterprises or organizations. | 0.663 | 0.835 | |

| 13. Our enterprise establishes shared information-sharing channels with other enterprises or organizations. | 0.636 | 0.889 | 0.881 |

| 14. Our enterprise regularly interacts with other enterprises or organizations to discuss professional issues related to product services. | 0.776 | 0.835 | |

| 15. Our enterprise often acquires new knowledge about products and services from other enterprises or organizations. | 0.793 | 0.829 | |

| 16. Our enterprise learns and follows up on other enterprises’ or organizations’ innovations in ecological products and services. | 0.778 | 0.836 | |

| 17. Our enterprise has a history of referring customers to other tourism-related enterprises. | 0.563 | 0.844 | 0.841 |

| 18. Our enterprise has a history of collaborating with other tourism-related enterprises to develop products and services. | 0.704 | 0.793 | |

| 19. Our enterprise is better developed through cooperation with other tourism-related enterprises. | 0.711 | 0.787 | |

| 20. Our enterprise cooperates with other tourism-related enterprises for mutual benefit. | 0.753 | 0.764 | |

| 21. Our enterprise has helped to create a distinctive ecological tourism brand identity for the area. | 0.694 | 0.792 | 0.838 |

| 22. Our enterprise helps scenic areas to build and maintain a good image of the place to visit. | 0.759 | 0.773 | |

| 23. Our enterprise helps to raise the profile of the scenic area. | 0.733 | 0.779 | |

| 24. Our enterprise relies on external perceptions of the landscape as a whole to access customer resources. | 0.474 | 0.853 | |

| 25. Our enterprise is bound to regulate its own behavior in order to maintain the reputation of the scenic area. | 0.595 | 0.822 |

| Factor Name | Cronbach’s | CR | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental activism behavior | 0.811 | 0.8049 | ||||||

| Environmental citizenship behavior | 0.777 | 0.7847 | ||||||

| Dialogue communication behavior | 0.846 | 0.8004 | ||||||

| Knowledge-sharing behavior | 0.889 | 0.7774 | ||||||

| Co-opetition behavior | 0.844 | 0.8139 | ||||||

| Reputation building behavior | 0.853 | 0.8478 | ||||||

| Average Value | Standard Deviation | Environmental Activism Behavior | Environmental Citizenship Behavior | Dialogue Communication Behavior | Knowledge-Sharing Behavior | Co-Opetition Behavior | Reputation Building Behavior | |

| Environmental activism behavior | 5.91 | .97 | 1 | |||||

| Environmental citizenship behavior | 5.46 | 1.12 | 0.518 ** | 1 | ||||

| Dialogue communication behavior | 5.68 | 1.07 | 0.495 ** | 0.461 ** | 1 | |||

| Knowledge sharing behavior | 5.11 | 1.36 | 0.502 ** | 0.530 ** | 0.581 ** | 1 | ||

| Co-opetition behavior | 5.60 | 1.28 | 0.375 ** | 0.444 ** | 0.519 ** | 0.535 ** | 1 | |

| Reputation building behavior | 5.95 | 1.09 | 0.434 ** | 0.448 ** | 0.473 ** | 0.450 ** | 0.480 ** | 1 |

| Indicators | Category | Number | Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample source | Wulingyuan | 75 | 34.1% |

| Tianmen Mountain | 34 | 15.5% | |

| Mount Huang | 85 | 38.6% | |

| Other (online) | 26 | 11.8% | |

| Main business | Accommodation | 123 | 55.9% |

| Food&Beverage | 45 | 20.5% | |

| Retail | 41 | 18.6% | |

| Travel agents | 10 | 4.5% | |

| Other | 1 | 0.5% |

| Absolute Goodness of Fit Index | Value-Added Goodness of Fit Index | Simplified Goodness of Fit Index | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | /df | RMR | RMSEA | NFI | RFI | IFI | TLI | CFI | PGFI | PNFI | |

|

the Smaller

the Better | <5 | <0.5 | < | > | > | > | > | > | > | > | |

| M6 | 897.663 | 3.990 | 0.167 | 0.117 | 0.736 | 0.729 | 0.788 | 0.782 | 0.788 | 0.610 | 0.717 |

| M6’ | 687.556 | 3.154 | 0.140 | 0.099 | 0.798 | 0.786 | 0.852 | 0.843 | 0.852 | 0.665 | 0.753 |

| M4 | 405.931 | 5.486 | 0.170 | 0.143 | 0.823 | 0.814 | 0.851 | 0.842 | 0.851 | 0.614 | 0.781 |

| M4’ | 176.195 | 3.091 | 0.102 | 0.098 | 0.915 | 0.901 | 0.941 | 0.931 | 0.940 | 0.650 | 0.790 |

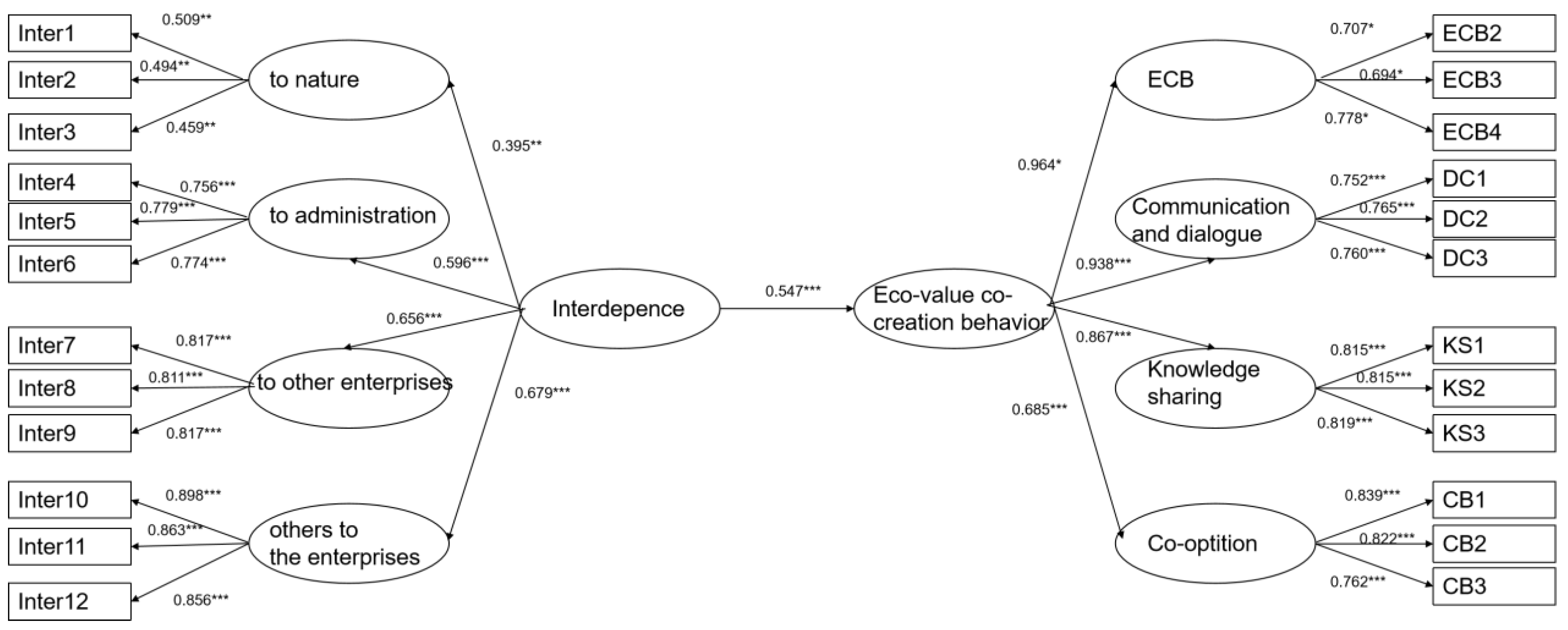

| Factor | Measurement Projects | Confirmatory Factor Analysis | CITC | Cronbach’s | Portfolio Reliability CR | Average Variance Extraction Value AVE | Multirelated Square SMC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standardization Load Value | T-Value | p-Value | |||||||

| Environmental citizenship behavior | ECB2 | 0.706 | 3.105 | ** | 0.743 | 0.498 | |||

| ECB3 | 0.695 | 3.116 | ** | 0.721 | 0.826 | 0.7706 | 0.5289 | 0.483 | |

| ECB4 | 0.778 | 3.100 | ** | 0.600 | 0.606 | ||||

| Dialogue communication behavior | D1 | 0.752 | 2.756 | ** | 0.768 | 0.565 | |||

| D2 | 0.766 | 2.752 | ** | 0.803 | 0.881 | 0.8034 | 0.5766 | ||

| D3 | 0.760 | 2.771 | ** | 0.740 | |||||

| Knowledge sharing behavior | KS1 | 0.816 | 7.714 | *** | 0.796 | 0.665 | |||

| KS2 | 0.815 | 7.707 | *** | 0.852 | 0.918 | 0.8573 | 0.6669 | 0.665 | |

| KS3 | 0.819 | 7.752 | *** | 0.854 | 0.671 | ||||

| Co-opetition behavior | CB1 | 0.839 | 12.151 | *** | 0.734 | 0.703 | |||

| CB2 | 0.822 | 12.020 | *** | 0.825 | 0.876 | 0.8498 | 0.6539 | 0.676 | |

| CB3 | 0.763 | 10.927 | *** | 0.738 | 0.582 | ||||

| Latent Variables | Environmental Citizenship Behavior | Dialogue Communication Behavior | Knowledge Sharing Behavior | Co-Opetition Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental citizenship behavior | 0.727 | |||

| Dialogue communication behavior | 0.694 ** | 0.759 | ||

| Knowledge sharing behavior | 0.650 ** | 0.663 ** | 0.817 | |

| Co-opetition behavior | 0.480 ** | 0.546 ** | 0.724 ** | 0.809 |

| Models | Sig. | /df | RMR | RMSEA | NFI | RFI | IFI | TLI | CFI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Four-factor model | 176.195 | - | - | 3.091 | 0.102 | 0.098 | 0.915 | 0.901 | 0.941 | 0.931 | 0.940 |

| Three-factor model 1 ECB + CB | 327.435 | 151.240 | ** | 5.457 | 0.199 | 0.143 | 0.841 | 0.826 | 0.867 | 0.853 | 0.866 |

| Three-factor model 2 D + CB | 351.258 | 175.063 | ** | 5.854 | 0.195 | 0.149 | 0.830 | 0.813 | 0.855 | 0.840 | 0.854 |

| Three-factor model 3 KS + CB | 238.627 | 62.432 | * | 3.977 | 0.148 | 0.117 | 0.884 | 0.873 | 0.911 | 0.902 | 0.911 |

| Single-factor model | 384.383 | 208.188 | ** | 6.200 | 0.210 | 0.154 | 0.814 | 0.802 | 0.839 | 0.828 | 0.839 |

| Title Item | Cronbach’s for Dimensionality | Cronbach’s for the Variables |

|---|---|---|

| Inter 1 The enterprise is dependent on the natural resource environment for its development. | 0.751 | 0.834 |

| Inter 2 The importance of the natural resource environment is irreplaceable. | ||

| Inter 3 The loss of the natural resource environment would be a great loss to the enterprise. | ||

| Inter 4 The enterprise is dependent on the scenic management body for its development. | 0.863 | |

| Inter 5 The importance of landscape management bodies is difficult to replace. | ||

| Inter 6 The absence of a scenic management body would be a great loss to the enterprise. | ||

| Inter 7 The enterprise is dependent on other tourism enterprises for its development. | 0.825 | |

| Inter 8 The importance of other tourism enterprises to our enterprise is difficult to replace. | ||

| Inter 9 It would be a great loss to the enterprise if there were no other tourism enterprises. | ||

| Inter 10 The landscape is dependent on the enterprise for its development. | 0.925 | |

| Inter 11 The importance of this enterprise to the landscape is hard to replace. | ||

| Inter 12 The loss of this enterprise would be a great loss to the scenic area. |

| Title Item | Average Value | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| PEB1 | 5.99 | 1.188 |

| PEB2 | 6.24 | 0.969 |

| PEB3 | 6.09 | 1.119 |

| PEB4 | 6.02 | 1.203 |

| PEB5 | 5.94 | 1.279 |

| ECB1 | 5.47 | 1.326 |

| ECB2 | 5.35 | 1.389 |

| ECB3 | 5.56 | 1.368 |

| ECB4 | 4.97 | 1.605 |

| D1 | 5.40 | 1.428 |

| D2 | 5.23 | 1.428 |

| D3 | 5.19 | 1.458 |

| KS1 | 4.83 | 1.675 |

| KS2 | 4.92 | 1.697 |

| KS3 | 4.92 | 1.697 |

| CB1 | 4.78 | 1.831 |

| CB2 | 5.05 | 1.719 |

| CB3 | 5.28 | 1.565 |

| CR1 | 5.79 | 1.291 |

| CR2 | 6.04 | 1.214 |

| CR3 | 5.83 | 1.266 |

| CR4 | 6.17 | 1.013 |

| Average Value | Standard Deviation | Environmental Activism Behavior | Environmental Citizenship Behavior | Dialogue Communication Behavior | Knowledge Sharing Behavior | Co-Opetition Behavior | Reputation Building Behavior | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental activism behavior | 6.06 | 0.89 | 1 | |||||

| Environmental citizenship behavior | 5.34 | 1.22 | 0.494 ** | 1 | ||||

| Dialogue communication behavior | 5.27 | 1.30 | 0.399 ** | 0.679 ** | 1 | |||

| Knowledge sharing behavior | 4.89 | 1.57 | 0.358 ** | 0.649 ** | 0.663 ** | 1 | ||

| Co-opetition behavior | 5.04 | 1.53 | 0.293 ** | 0.472 ** | 0.546 ** | 0.724 ** | 1 | |

| Reputation-building behavior | 5.96 | 0.96 | 0.479 ** | 0.425 ** | 0.301 ** | 0.421 ** | 0.274 ** | 1 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nie, K.; Tang, X. Study on Ecological Value Co-Creation of Tourism Enterprises in Protected Areas: Scale Development and Test. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610151

Nie K, Tang X. Study on Ecological Value Co-Creation of Tourism Enterprises in Protected Areas: Scale Development and Test. Sustainability. 2022; 14(16):10151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610151

Chicago/Turabian StyleNie, Kang, and Xiaojing Tang. 2022. "Study on Ecological Value Co-Creation of Tourism Enterprises in Protected Areas: Scale Development and Test" Sustainability 14, no. 16: 10151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610151

APA StyleNie, K., & Tang, X. (2022). Study on Ecological Value Co-Creation of Tourism Enterprises in Protected Areas: Scale Development and Test. Sustainability, 14(16), 10151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141610151