1. Background

The need for sustainable tourism arose long before the COVID-19 global epidemic. As early as 2005, United Nations published a guide on sustainable tourism, which still provides the basics of the sustainable goal developments of the World Tourism Organization. The guideline—written within the framework of the United Nations Environment Program—addresses policy-makers and calls attention to creating sustainable tourism development projects and policies in order to protect the environment and local areas from overconsumption and exploitation [

1]. Thus, the focal points of the World Tourism Organization’s work regarding sustainable tourism development are the following: Optimal use of the environment, maintaining healthy ecological processes, respecting the host communities, and ensuring viable economic operations [

2]. The United Nations also designated the year 2017 as the International Year for Sustainable Tourism Development in order to encourage the policy-makers to contribute to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The threat of over-tourism seems real and more pressing than ever, even in the light of the coronavirus epidemic. Moreover, the epidemic—as a magnifier—actually exacerbates the problems that already existed regarding the tourist’s overconsumption. While the lack of tourists meant economic difficulties and hard times for international tourism, it also gave the opportunity for locals to regain back their living space. There was already a tension between the ambitious tourism development projects and the long-term sustainability, and a lot of the development projects left out social relations. When these kinds of projects met with failed regulations of natural resources, that made the situation even worse. The role of globalization in tourism growth is unquestionable. The unlimited access to information, the modernization of transport, free markets—that led to the expansion of international hotel chains—and the significant demand for touristic services had a huge impact on tourism growth [

3]. UNWTO’s Tourism Dashboard shows incredible growth between 2009 and 2019. While in 2009, the UNWTO registered 897 million international tourist arrivals, in 2019, this number was 1466 million [

4]. 2009 is an important year, as according to UNWTO, this was the year when international tourism receipts exceeded the number of international tourist arrivals permanently [

5]. Not to mention the non-conventional aspects of tourism mobility like one-day visitors, VFR tourism, which can hardly be detected in tourism statistics and is difficult to measure.

The rapid urbanization, affordable travel and visa services, technological advances, and new business models are all behind this rapid and monumental growth [

5]. The cheap flight tickets and constantly growing air transportation made the exotic destinations more reachable, and new consumer trends have appeared too. The considerable demand for touristic services accelerated development and made long-haul and foreign travels extremely popular.

The constantly increasing demand exceeded the level of sustainable tourism development. It is a legitimate question whether the socio-economically more vulnerable settlements, and especially the people living there, can actually benefit from the increasing demand. Different strategy-making levels have detached tourism as an economic sector from socio-economic and environmental impacts. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, there was already a call for more sustainable, smart, and local cities. Sustainability has gained greater importance as it contributes to today’s cities by making the lives of residents easier and offering sustainable and responsible management of natural resources [

6]. This backs up an argument about the carrying capacity of a tourism destination: What is the maximum number of visitors that is acceptable without destroying the environment and bothering local communities [

7]? Carrying capacity is linked to the tourist activities done within the region. These impacts have to be within the ecological carrying capacity of the given territory [

8].

The economic contribution of tourism has become so significant that the collapse of the industry has pointed out some serious problems that the COVID-19 pandemic could change in terms of sustainable tourism development. On the other hand, these changes should have been done long before the crisis, as the excessive growth means more vulnerability in the case of those countries and settlements where the main source of revenue is mass tourism.

The pandemic brought lockdowns, social distancing, travel bans, flight cancellations, and numerous health and safety risks, which obviously decreased the number of travels. The pandemic shows signs that it could bring long-term changes in the industry and re-imagine sustainable and responsible tourism [

9]. Achieving sustainable tourism and, at the same time, maximizing growth is always a challenge [

10] as usually, the cheap and convenient options are not the sustainable ones. It is also important to note that the tourism sector also significantly contributes to global greenhouse gas emissions [

11].

Due to the lockdowns and difficult travel regulations during the pandemic, the demand for domestic products has emerged. Tourists who usually choose long-haul and foreign travel routes were forced to travel within the country borders. This phenomenon led to more rational consumption. Tourism consumption starts when the traveler leaves his permanent home until he arrives home [

12]. It would be naive to expect rational behavior regarding sustainability from tourists who spend their free time, which often ends up in unreasonable decisions regarding the type of transportation, accommodation, shopping, and sightseeing. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, the younger generation still considers that the waste situation, pollution, use of non-renewable resources are the main challenges that sustainable tourism faces [

13]. Domestic travels—forced by the crisis—resulted at least in less air pollution. Nevertheless, distance is a critical factor in tourism. Variables such as gender, time factor, education, number of children, seasonality, and weather, largely determine the distance of the travels [

14].

In the case of a small country like Hungary, where domestic flights do not exist, it seems to be more environmentally friendly. Achieving high-value tourism is an old desire in Hungary’s tourism, which means attracting high-spending tourists and increasing the revenue from tourism expenditure instead of increasing the number of tourists. This could result in much more sustainable growth.

The Hungarian Tourism Agency is a governmental organization responsible for the development and public administration of tourism in Hungary. The organization’s main mission is to gain competitiveness of Hungary as a tourism destination and to promote the country in order to be more attractive for international, domestic, and business travelers. The Hungarian Tourism Agency defines the tourism development strategy, supervises the utilization of EU funds and domestic budgetary sources dedicated for tourism development and manages the tourism brand of Hungary [

15]. As part of the governmental tasks, the organization issued the National Tourism Development Strategy in 2017, which includes all the guidelines regarding the tourism development in Hungary until 2030. The strategy was updated in 2021 due to the COVID-19 circumstances, and the National Tourism Development Strategy 2.0 version was born. The strategy places a strong emphasis on sustainability and responds to the ever-changing trends in tourism. Due to the destination approach, territorial aspects are also prominent, providing a framework for defining the profile of each touristic region. This also helps specific regional branding. According to the strategy’s vision, by 2030, the tourism sector in Hungary will be the driving force for sustainable economic development by achieving quality experience, innovative solutions, and a strong national tourism brand. The strategy dedicates a whole chapter to sustainability as a strategic direction, in line with international standards. One of the long-term goals is the introduction of a trademark developed along sustainability criteria that is widely applicable in the tourism sector. Sales efficiency is essential for sustainable growth. In addition to this, professional marketing activities are indispensable to exploit the potential of domestic tourism. Data-driven and targeted marketing is needed as it is extremely important to restore demand as soon as possible after the significant decline in tourism as a result of the epidemic crisis [

16].

It can be clearly stated that tourism has many social and economic effects and advantages. This is especially true for the field of spa and health tourism, that generates longer stays and, therefore, high expenditures. Spa and health tourism is extremely important in countries like Hungary, which are on the one hand, weak in natural resources but, on the other hand, rich in natural thermal water. Under the territory of Hungary, there is a presence of 70% of thermal water, which is a remarkable gift. There are many settlements spread across Hungary that are blessed with thermal water that differ in terms of size, accommodation facilities, and faculties.

This study reveals two different dimensions of tourism typology. One of them are the characteristics of the receiving areas (Hévíz and Zalakaros), and the other are the characteristics of the visitors on the demand side. According to Candela and Figini [

17], it is debatable that the destinations are at the core of the tourism system, and they also argue that choosing a destination is at the center of decision-making. Health tourism, that is examined in this study, is one of the most popular tourism products in Hungary, which can be spotted in those settlements where thermal water is available. Analyzing its generated effects is quite important in the context of the changes caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Previous studies have already examined the socio-economic changes in the case of bath regions, e.g., the case of Kehidakustány, another well-known spa settlement in Hungary. It turned out that those cities which are successful in health tourism have the possibility to gain a higher level of income, which results in a major economic role [

18]. Obviously, higher income also contributes to the social development and satisfaction of the local society.

2. Data Collection and Research Methods

Our study uses quantitative methods based on secondary analysis of tourism statistics. There are several possible methods for measuring tourism demand. In the case of Hévíz and Zalakaros, which are typically multi-day destinations with a relatively long stay of the guests, accommodation statistics provide reliable information on the volume of tourism demand. The primary source of the examined data is the National Tourism Data Center (NTAK) database. The digital platform operating under the supervision of the Hungarian Tourism Agency allows the anonymous traffic statistics of all accommodation establishments in the country to be displayed in real time. From the data received directly through the accommodation management software, analyses are made to make the data-driven decisions needed to support the tourism profession. NTAK also has a significant role in the whitening of the tourism sector, as the territorially competent local governments and the National Tax and Customs Office also have an overview of the data areas that are relevant to them. The NTAK receives statistical data from the individual accommodation management, catering and ticketing software. For our study, we obtained data gathered between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2021. To present the accommodation offer of Zalakaros and Hévíz, the capacity data of the accommodations registered in the NTAK digital platform (number of accommodations and offered rooms), which operates with complete coverage in the two settlements. To examine the characteristics of tourism demand, guest traffic data were aggregated according to the age groups and place of residence of guests, in the case of both Zalakaros and Hévíz. Regarding the applied methodology, it was a challenge that the NTAK database would be completely operational only from the beginning of 2020, therefore, the analysis examining the multi-year perspective is based on the freely available database of the Hungarian Central Statistical Office (CSO), which is limited to changes in the volume of tourism traffic and does not cover the demographic and geographical characteristics of domestic demand. As, unfortunately, there are no detailed data on the spatial pattern of domestic demand for the period before the Covid, other alternative methodological approaches are warranted to investigate this in the future.

3. Study Area

The research focuses on two Hungarian spa towns—Hévíz and Zalakaros—due to their international importance. They are located in the western part of Lake Balaton Touristic Region, the most important tourist destination in Hungary (

Figure 1). The tourist area of Lake Balaton has the largest accommodation capacity after Budapest (60,600 rooms) and, accordingly, the most visited rural tourist area, with a total of 5874 thousand guest nights, of which 67.38 percent are domestic, 32.62 percent foreign (31% German, 11% Czech, 11% Russian and 10% Austrian). Its main tourist products are waterfront holidays and thermal baths (source: CSO 2019). Lake Balaton has appreciated in recent years, and by the summer of 2021, we could see the operation of the previous successful years almost entirely.

The area has a quite good location and geographical position: The accessibility of the area is mainly determined by the E71 (M7) motorway and Hévíz-Balaton Airport, which is of exceptional importance for the West-Balaton destination, but the north-south transport possibilities need to be improved.

Hévíz, as a small town, has approx. 4800 inhabitants, with international second-home owners—mostly German and Russian—as well. The basis of tourism in Hévíz is the world-famous and unique Lake Hévíz and the medical tourism services based on it. The lake has a water surface of 44,400 square meters and is the world’s largest naturally warm, biologically active spa lake. The medicinal water erupts from the spring crater at a depth of 38 m, its average summer temperature is 33–35 °C, but it does not fall below 23 °C in winter, so it is suitable for outdoor swimming all year round. The water contains sulfur, alkali bicarbonate, slightly radon ingredients, which can primarily cure various rheumatic, musculoskeletal, and gynecological diseases [

19]. The central spa was built in 1795 on the initiative of Count György Festetics, the owner of the area. In recognition of the development, Hévíz was declared a spa settlement in 1911. On 1 January 1952, the Hévíz State Spa Hospital was established in the buildings of the spa, which is now the St. Andrew’s State Rheumatology and Rehabilitation Hospital. Due to this, Hévíz has become the largest spa in the country for the treatment of musculoskeletal rheumatic diseases. In 2015, Hévíz created its own trademark for the accreditation of therapies based on the healing effects of Lake Hévíz. Institutions that have the necessary professional, medical background, and medical infrastructure for the treatment (e.g., spa pool, weight bath, mud packer) are entitled to wear the trademark. There are currently nine certified spa hotels under the trademark that provide treatments under sanitary conditions under medical supervision. The last 30 years saw a greater development than ever before: Many new restaurants and hotels have been built. Recent spa and accommodation developments have aimed to increase the quality of care for patients recovering here.

Zalakaros—with approx. 2100 inhabitants—has also become one of the most important Hungarian international spa destinations. The flourishing of the settlement can be clearly linked to the construction of the spa. In 1962, during the hydrocarbon exploration in Zala, hot thermal water was found in the settlement. The spa opened in 1965, and the settlement underwent a significant development, the plans for the development and arrangement of the village and the recreation area were completed in a decade. The year of 1975 was decisive, when the building of the indoor bath was handed over, so the seasonal nature of the bath in Zalakaros ceased to exist and the basic conditions for the medical utilization of the thermal water were established. In the following years, the spa continued to expand, and new pools were built, significantly increasing the water surface. In 1978, the Granite Spa was declared a recognized spa. The spa developments of the last 10 years have focused on the needs of the guests with children, families and young adults looking for wellness and adventure bathing, pushing the development of medical products into the background. In parallel with this, the capacity of tourist accommodation has been constantly increasing, new hotels and private accommodation have been established in the settlement.

4. The National Significance of the Two Cities, Based on Visitor Traffic and Capacity Data

The region of Western Balaton is one of the most visited destinations in Hungary. Hévíz and Zalakaros are the two most important spa resorts in the country in terms of available accommodation services. There were 653 accommodation establishments in Hévíz in July 2021, offering a total of 3920 rooms, while in Zalakaros, there were 2332 rooms available. The offer of both settlements is dominated by hotels, with more than half of the capacity being supplemented by private accommodation and other accommodation. Despite the fact that the attractiveness of both settlements is focused on medicinal water, the two settlements address fundamentally different target groups. Hévíz is an internationally known spa town with a significant foreign tourist turnover (675.3 thousand), while Zalakaros was the number one medical tourist destination in the country in terms of domestic tourism in 2019, with 508.1 thousand domestic guest nights. In the years before the epidemic, more than half of Hévíz’s guest traffic was generated by foreign tourism, while in Zalakaros, less than a quarter of the guests were foreign (

Figure 2).

5. Impact of the COVID-19 Epidemic on Tourism in the Region

Before presenting the changes caused by Covid, it is worth looking at the state of the Hungarian tourism sector and the two settlements before the pandemic started. The 2010s were about the prosperity of the Hungarian tourism industry, with a steadily increasing performance year by year. Concentrating on the two settlements examined, the guest turnover of Hévíz increased by more than a fifth, the growth of the tourism performance of Zalakaros exceeded 60% in the period between 2010 and 2019. In 2020, the Covid epidemic hit the Hungarian tourism sector hard, causing serious economic and social changes, especially in areas with a strong tourist profile, such as the West Balaton region. The negative effects of the epidemic on tourism performance were severe in both settlements. According to the data from the Hungarian Central Statistical Office, the number of foreigners visiting Hévíz fell by almost a fifth in 2020 compared to 2019, but there was also a decrease of about 40% in the case of domestic demand. In Zalakaros, the foreign guest turnover decreased by almost 70%, while the number of domestic guest nights decreased by about 30%. Due to the drop in demand and the uncertainty surrounding the conditions of international tourism, the spa settlements had to reach new target groups after the lifting of the epidemiological restrictions. In our analysis, the national, demographic, spending, and territorial characteristics of the volume of guest traffic in Hévíz and Zalakaros for the period following the outbreak of COVID-19 are presented.

6. Results

In 2020, compared to previous years, a drastic decline in foreign demand could be observed, and based on turnover data, the number of foreign guests returned only partially to the two settlements in 2021. In the case of Hévíz, with the loss of the previously dominant foreign target groups, domestic demand gave approximately two-thirds of the guest nights in 2020 and 2021, while the share of domestic demand continued to grow in Zalakaros, which has traditionally been strong on domestic guests (

Table 1).

The common feature of the guests of the two settlements is the high proportion of guests using wellness and health tourism services (MTÜ, 2016). In addition to the similarities, however, the two spa towns address significantly different target groups. Nearly two-thirds of Hévíz’s guests are people over the age of 45, whose main motivations are rest and health. In contrast, Zalakaros is characterized by a younger group of guests, with more than 60% of guests in Zalakaros under the age of 45. A significant proportion are couples between the ages of 35 and 45, who often arrive on long weekends, and those who go on family vacations to Zalakaros. The twenty-year-olds are underrepresented in both settlements. It can also be said that the demographic characteristics of foreign and domestic demand are significantly different for both settlements. In the case of foreign markets, well-defined target groups can be observed (

Figure 3).

The base of Hévíz’s foreign target market is provided by the senior age group, which can be characterized by a long stay and is looking for high-quality health tourism services. Two-thirds of the income from foreign tourism of accommodation establishments in Hévíz is related to people over 55 years of age, mostly people over 65 years of age. In Zalakaros, however, foreign guests are mainly couples between the ages of 35 and 44, who are primarily attracted by wellness services. More than half of Zalakaros’ income from foreign tourism can be attributed to this age group. The group of foreign visitors to the two settlements is not homogeneous, different foreign target groups can be identified on the basis of nationality, length of stay, demographic characteristics, and spending habits.

The German market provides a significant part of the senior population visiting the area. The German seniors visit both settlements in large numbers, spending six to seven days at the destination. As the only place in Hungary, one of the dominant target groups of Hévíz is the Russian guest group, which is mainly a group of solvent, middle-aged, and elderly couples with a long stay. Russian demand is quite concentrated in Hévíz, there is no interest in the wider region. The number of Russian guests has been declining in recent years. By far, the German and Russian guests spend the most on accommodation. Due to the geographical proximity and the good value for money of the destination, many people come to the area from the border areas of Austria. In the case of the Czech and Slovak guests, it can be clearly observed that the older age groups visit Hévíz, while a higher proportion of people between the ages of 35 and 44 visit Zalakaros. Guests from the Czech Republic, Poland, and Slovakia are not only looking for premium accommodation, they have a significant need for mid-range services as well. Czech guests are characterized by average, Slovak and Polish guests by low unit spending, although the number of active families with medium and higher status is increasing from the Czech and Slovak sending markets. The stagnation or moderate decline of the sending markets (Germany and Russia), which provide the largest volume of guest traffic in the region, may be offset by the growth of these markets, which have additional potential and are less concentrated in Hévíz and visit the wider destination in large numbers (

Table 2). Other countries sending a significant number of guests include Ukraine, Switzerland, and Romania, which also have growth potential. In the pre-Covid period, groups of visitors from outside Europe, mainly from China and Israel, which generated a significant amount of traffic in Hévíz, almost completely disappeared from the region in 2020 and did not return in 2021.

It is important to emphasize that the specific expenditure of foreign guests is significantly higher than that of domestic guests. In the case of Hévíz, the expenditure per guest was 87.3% higher in the case of Zalakaros and 41.2% higher among foreign guests in 2021. The greatest contrast is in the comparison of foreign and domestic seniors. Foreign guests over the age of 65 spend 2.5 times as much on average in Hévíz and 2.2 times in Zalakaros as Hungarian guests. The difference is much smaller among the younger age groups. Data from recent years, on the other hand, show that this long-standing finding that foreign visitors are highly profitable for caterers appears to be declining on the basis of data from recent years. Partly as a result of the epidemic situation and state measures to encourage domestic tourism, a large number of solvent Hungarian guests have appeared, and their returning guests may be of strategic importance to the spa settlements.

Domestic demand is becoming more and more important in the tourist traffic of the West-Balaton destination, which is significantly more diverse in terms of demographics than foreign visitors. Among the domestic tourists of Hévíz, in addition to the traditionally large number of seniors, the 35–44, 45–54, and 55–64 age groups also come to the spa settlement in similar numbers. The over-55 age group stays almost exclusively in hotels, while the share of private accommodation and other types of accommodation is high (30–40%) for the younger age groups. Regarding the spending per guest, a significant difference can be identified between the groups of guests under 35 (HUF 43,329) and those over 35 (HUF 54,758). There is no significant difference in the comparison of the 10-year age groups of those over 35 years of age. In the case of Zalakaros, the largest proportion of domestic guests are between the ages of 35 and 44 (30%), while the second largest age group is under the age of 18. It is clear from the data that Zalakaros is a typical destination for domestic family holidays, mainly during the summer months of the season. Families do not only stay in hotels, almost 20% of them choose private accommodation. In the age group between 35 and 44, another solvent target group arriving without children can be identified, which is characterized by high specific spending (HUF 73,289) compared to the other age groups, which is catching up to the spending intensity of foreign guests. The number of visitors to this target group increased almost one and a half times in Zalakaros in 2021 and 2020, while the number of visitors with families did not change significantly based on the number of registered guests under the age of 18. In the summer of 2021, the capacity utilization showed values above 80%, domestic demand in 4- and 5-star hotels was able to make up for the lost foreign guest traffic in the summer. This is the young and middle-aged group, who presumably travel abroad, are characterized by high spending, are less price sensitive, but chose domestic destination in the summer of 2021 due to the uncertainty caused by Covid. On the other hand, domestic demand showed moderate interest in lower-category hotels. Pre- and post-season traffic lagged behind, thus strengthening the seasonality that used to be generally less common in spa towns.

The spatial pattern of tourism demand in Hungary is less a Covid-related phenomenon than a phenomenon determined by the urbanization processes and changes in the spatial pattern of development of the past decades, which in Hungary has two main dimensions: The metropolitan–rural (center–periphery) contrast and the west–east regional inequalities, it means the division of the country is quite sharp [

20]. Due to the strongly unipolar spatial structure of Hungary [

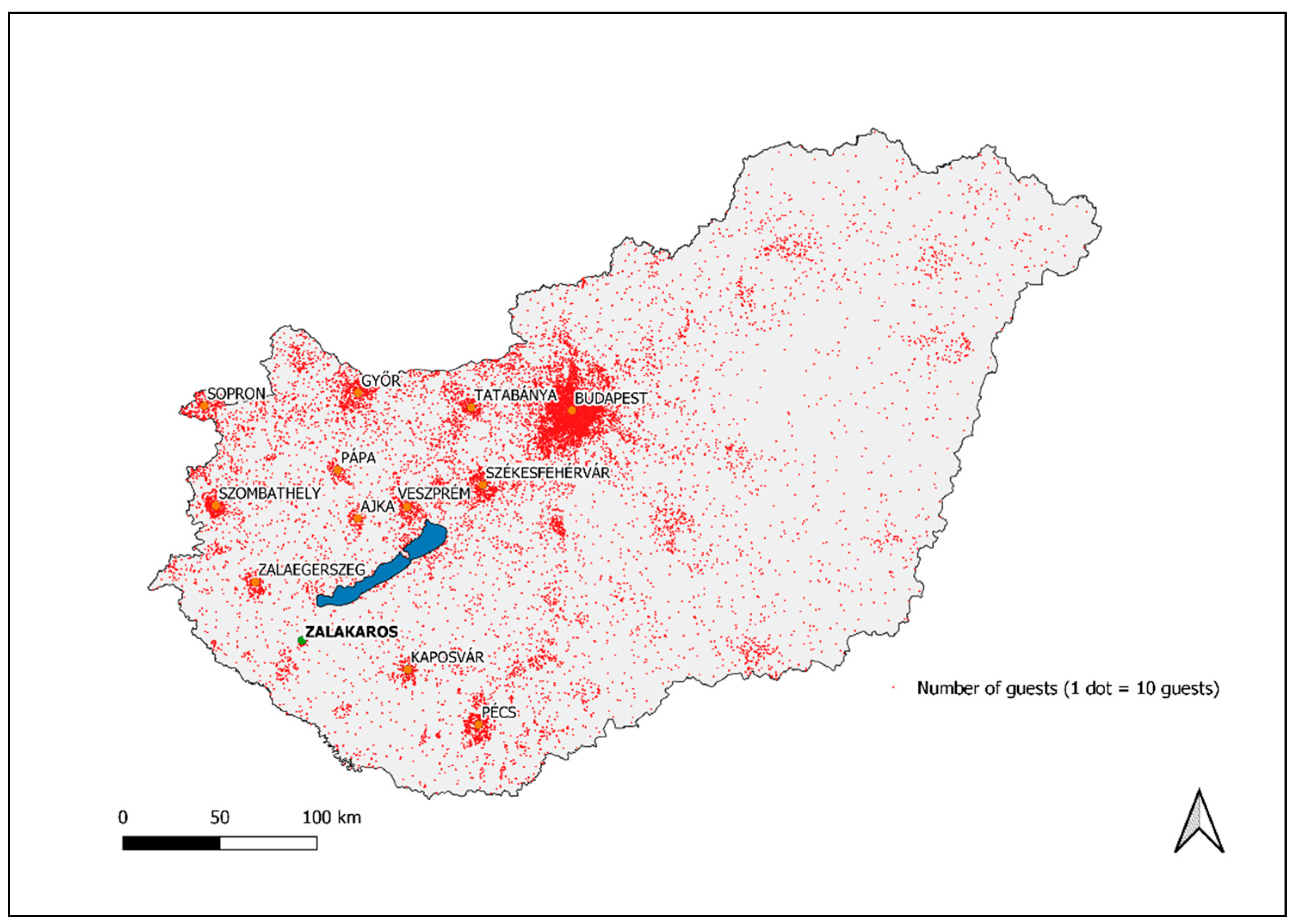

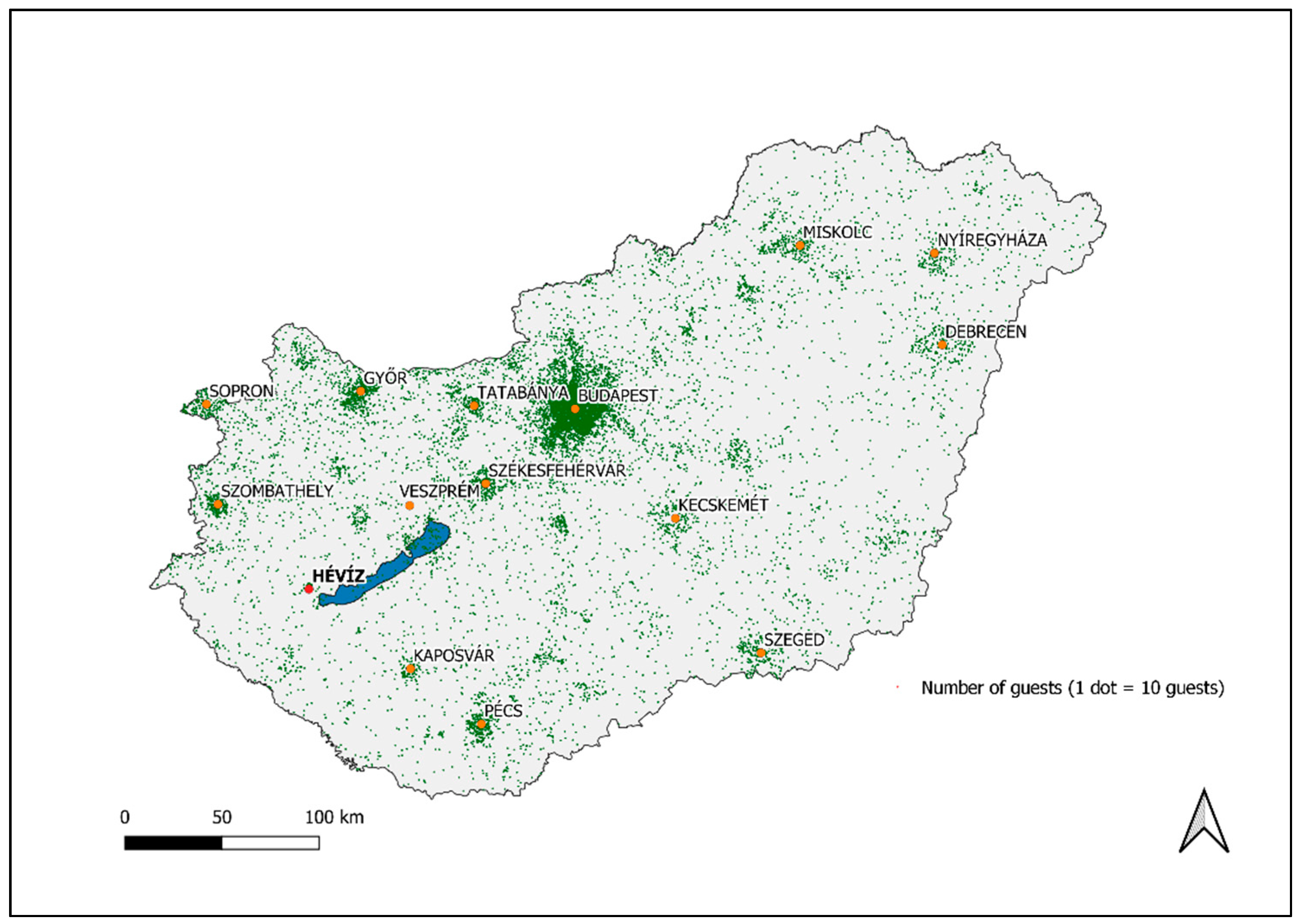

21], the metropolitan area of Budapest, like in the case of many other socio-economic phenomena, plays a prominent role in terms of the territorial distribution of tourism demand. The distribution of domestic demand in Zalakaros and Hévíz by destination area is represented by dot density maps (see

Figure 4 and

Figure 5), where one point represents 10 guests. As shown by spatial data, the majority of domestic guests—24% in the case of Hévíz and 17% in the case of Zalakaros—come from Budapest. The capital city and its growing agglomeration are increasingly dominant in terms of economic, technological, cultural, and human resources [

22], and as a result, the purchasing power and potential target groups for spa towns are also predominantly concentrated in the metropolitan region. Satellite towns around Budapest with a high standard of living are among the most important sending areas of the West Balaton region: Not only because of the better geographical location, but the higher status population could offer to reach these settlements for holidays.

Comparing the domestic traffic of the two cities (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5), it can be stated that Zalakaros is much more of a destination with regional significance, with an area extending to the west of the Danube (Transdanubia), while Hévíz is a nationally known and visited destination. Apart from the Budapest area and the city of Pécs, the main Hungarian sending cities of Zalakaros are exclusively Transdanubian cities (Székesfehérvár, Győr, Szombathely, Veszprém, Sopron and Tatabánya). Important sending towns—such as Veszprém, Zalaegerszeg, Ajka, Pápa, and Kaposvár—are situated within 100 km of the destination. In the case of Hévíz, Pécs, Győr, Székesfehérvár, Sopron, and Szombathely are dominant markets as well, but Hévíz is also visited in large numbers from the cities of Northern Hungary (Miskolc), the Northern Great Plain (Debrecen, Nyíregyháza), and the Southern Great Plain (Kecskemét). We can conclude that the attractiveness of Hévíz extends to a wider area, geographic proximity seems to be less important for the visitor flows of Hévíz. Looking at the sending areas of the region in the light of the spatial structure of Hungary, it can be seen that the two settlements tend to target more developed urban agglomerations with a higher standard of living, which is also reflected in the increasing trend of the expenditure structure.

In the case of Hévíz, the analysis of the new type of database made the reorganization of the target groups even more visible, which resulted primarily in 2020 from the fact that the guests of the classic spa treatments of the pre-pandemic period (German seniors and Russian spa guests) became unavailable due to the restrictions, and a proportionally larger share of the thus reduced traffic reached the traffic of domestic and neighboring countries. The data analysis clearly highlights the need for a drastic transformation of the target groups, as well as the creation of a new image of Hévíz. The city’s new marketing strategy responded to this change, on the basis of which, sports and slow tourism, as well as the Post Covid Care program, are currently in focus, still addressing target groups with a higher ability to pay [

23]. However, it is important to mention that the transformational effect of the processes of the past years on the long-term target group cannot yet be established based on the data from 2021.

In the case of Zalakaros, in the years prior to the pandemic, the spa town already placed family-friendly experience bathing and wellness bathing in the focus of its product development and marketing strategy instead of being an exclusive health resort mainly aimed at young, family customers from domestic and neighboring countries [

24]. The travel restrictions affected these target groups less, so they were able to further strengthen the already started communication and act effectively in the changed tourism market. In the case of Zalakaros, the change in the target group can already be clearly seen from the statistical data from 2021, which is also helped by the fact that the investments affecting the young age group were realized in connection with the urban development (walking route around the artificial thermal Lake and Ecopark, thus increasing the settlement as a family-friendly tourist destination appearance.

7. Conclusions

The last two years have caused a significant change in the life of the two settlements, which clearly made it necessary to rethink the target groups. From the data of returning guests, it is clear that people’s desire to travel is unbroken. Despite the restrictive measures, they are looking for travel opportunities. As a result, the role of stable domestic demand is becoming more important for individual destinations.

Hévíz is the number one tourist settlement in Hungary after the capital, however, it was most severely affected by the pandemic, with a 62% shortage of visitors. One of the main reasons for the large decline is the slower return of senior (over 65) foreign visitors to the destination. This is intensifying this year, as the Ukrainian–Russian conflict is clearly making its mark on the lack of the current main sending market—in the case of Hévíz—which must be filled with a new strategy by renewing the supply market and brand of the settlement. Here we can clearly relate to the issue of sustainability: Is the settlement able to renew itself, address the domestic market sufficiently, adjust its offer to the Hungarian—primarily high-status clientele, establish a network connection in the region—one of the elements of which is sustainability in connection with domestic travel? In the city of Hévíz, the service providers have started their activities in this direction, i.e., a completely new target group: In addition to the seniors, the family has become the most important potential target group, targeting those interested in hobby and professional sports tourism. In addition, it has launched a new health tourism product package called “Post Covid Care” that offers standardized treatment packages using existing medical experience and medical infrastructure as part of private health care in a quality hotel environment. For Hévíz, due to its distinctive medical tourism image, adult-friendly, age-restricted tourism products can also be a competitive advantage, which can also be unique, attractive products for the target groups of the domestic and surrounding countries.

In the city of Zalakaros, the service providers were in a less vulnerable position to the markedly present foreign sending market, so the transformation, addressing the guests, offering the service providers, rethinking the brand of the city created an easier situation: Addressing the domestic target group, being active on social media, using new urban attractions and programs for the young age group clearly have the effect of changing the city’s clientele. Sustainable product development opportunities should be to develop for the new domestic clientele. In Zalakaros, ecotourism (through the protected areas of the Kis-Balaton National Park) and active tourism have been further strengthened, but there are untapped opportunities to address the young adult clientele with high wellness, such as manager disease management, burn out programs, immunity boosting, and post-Covid cures.

From the development of demand and the comparison of the two settlements, it can be seen that the domestic guests are mainly couples aged between 35 and 45, looking for a wellness experience, not a treatment based on balneotherapy. This attitude could only be changed by shaping a long-term national approach.

Based on the new type of database (the National Tourism Data Center) examination, we can highlight the fact that the two settlements, Hévíz and Zalakaros, have two similar attractions, but their guest structure, destination areas, and future perspectives have changed radically in the last two years. The differences are also very clear in terms of the domestic market of the two spa towns: While in the case of Hévíz, the medicinal character generated many guests from the eastern part of Hungary, also from the big cities (which means that the people living in the big cities have higher status), in the case of Zalakaros, the sending area of the guests affects the more developed western region. This can also be attributed to the fact that in the eastern part of the country, the people living there can visit many family-friendly settlements with medicinal water, meaning that it is not worth it for them to travel to a more distant settlement, while in the case of Hévíz, the unique medicinal character generates greater and higher-status purchasing power.

The examples show that in the short term (1–2 years), destinations (without external help) cannot introduce a new product and reach a large number of new target groups, even though product development is taking place. Introduction and promotion of the market require regional or state-level resources. A suggestion for both settlements is that much more attention should be paid to the National Tourism Development Strategy 2.0. the goals of creating sustainable destinations, the development and communication in this direction at the local level, the implementation of a conscious attitude formation, as a result of which a much more conscious, high-quality clientele seeking recreation, healing, and sustainability can flow into the region.