Localisation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Bangladesh: An Inclusive Framework under Local Governments

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. SDGs: Adoption and Implementation

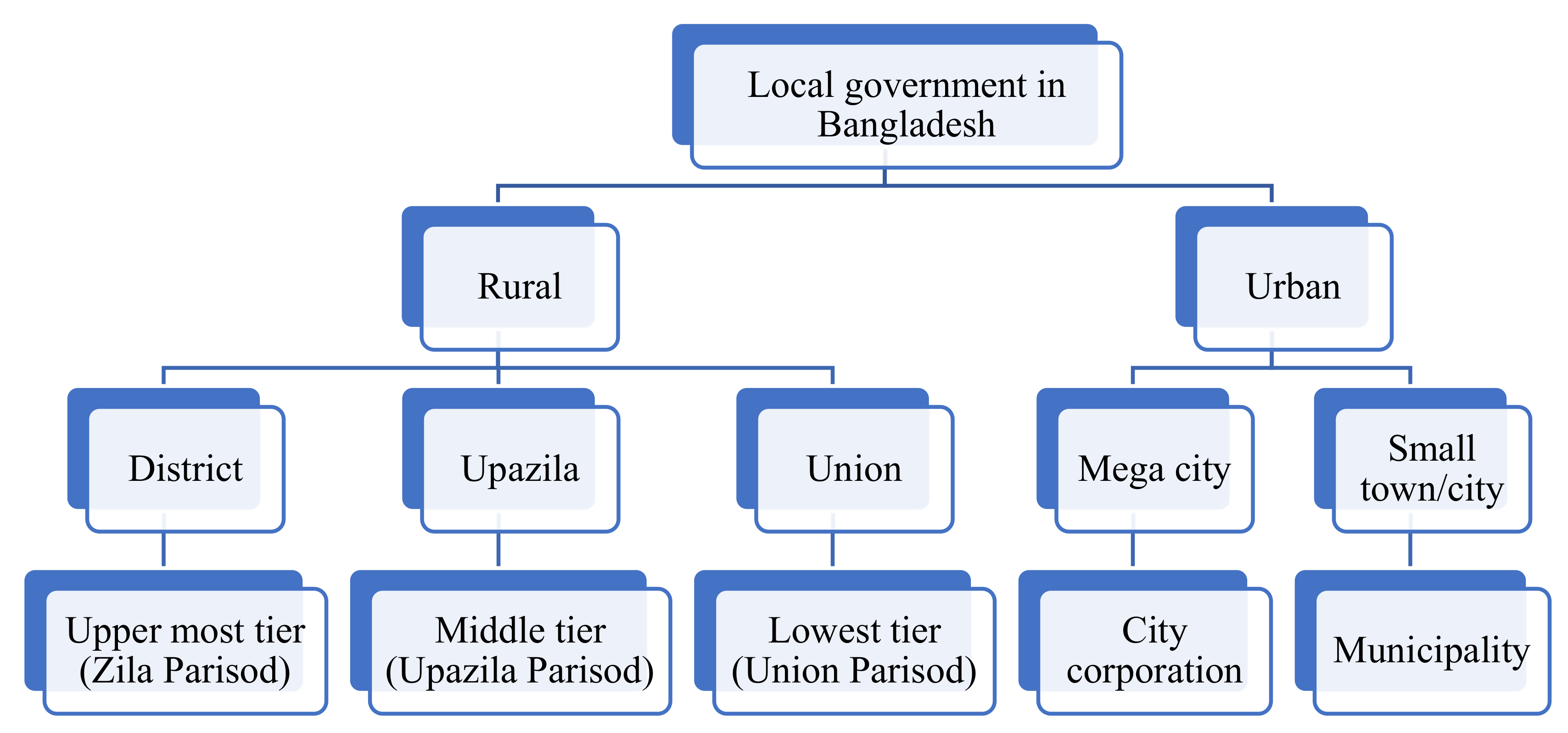

2.2. SDG Linkages with Local Government

2.3. Bangladesh Effort toward SDG Localisation: Experience from the MDGs

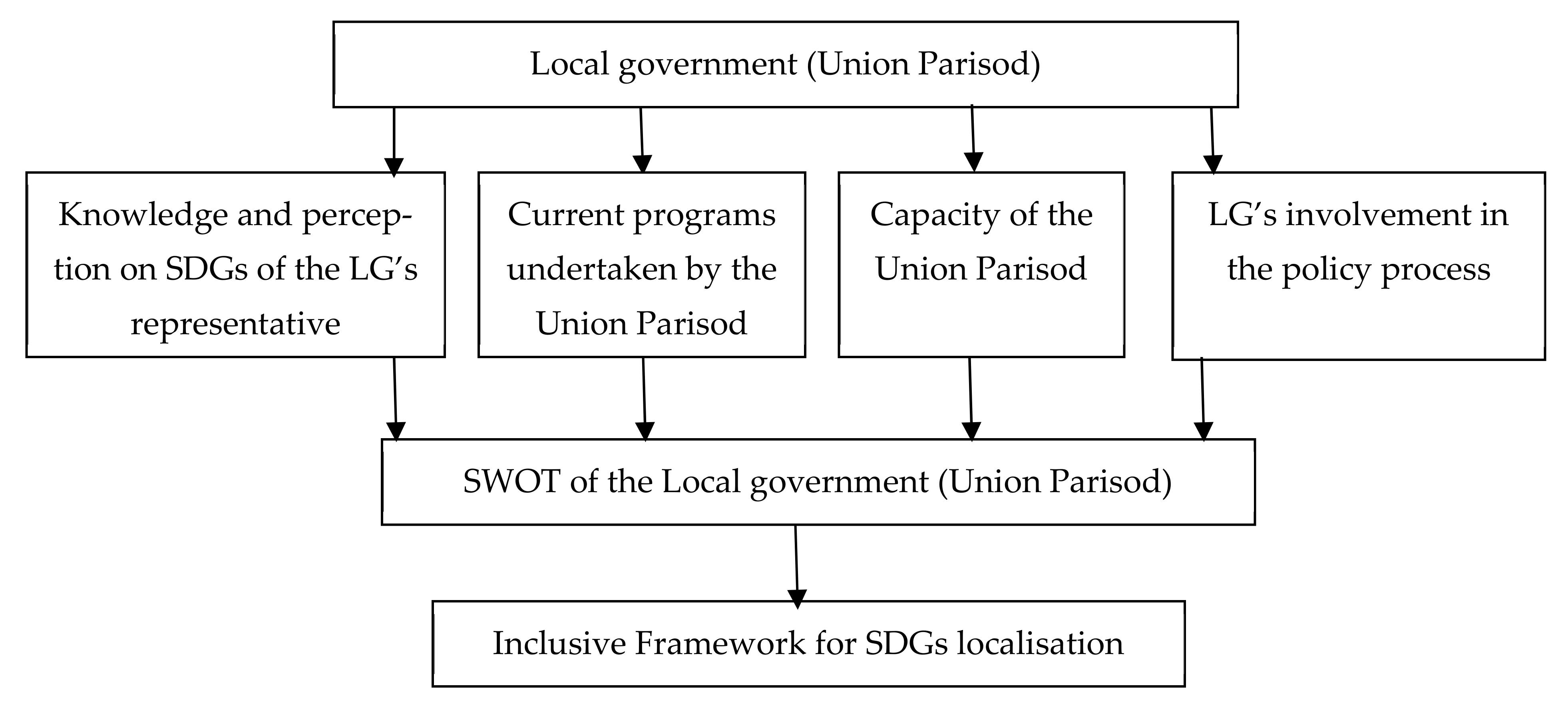

3. Methodology

4. Results and Discussion

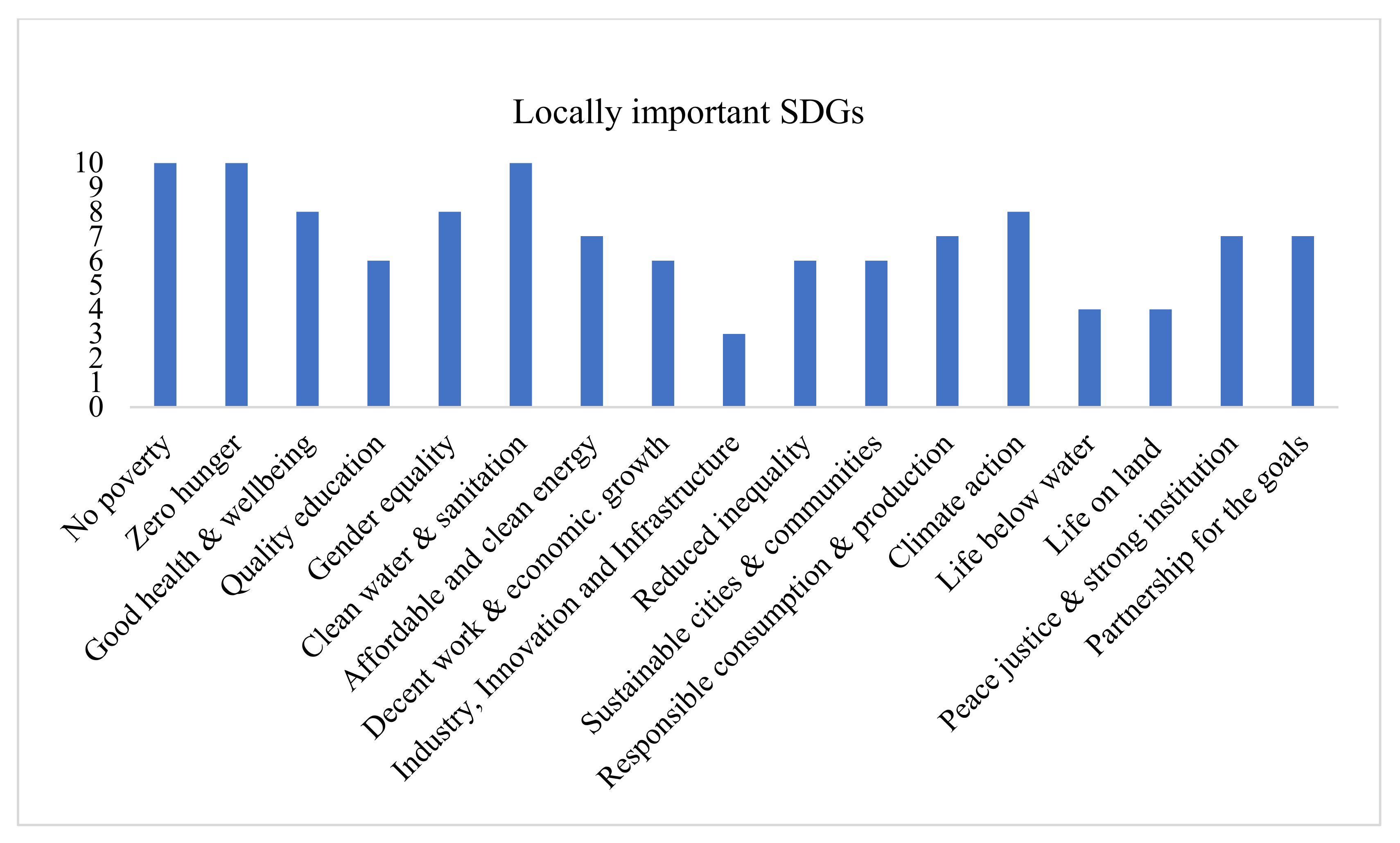

4.1. Knowledge and Perception of the Respondents Relating to the SDGs

4.2. Current Programmes Undertaken by the Union Parisod

4.3. Capacity of Local Government

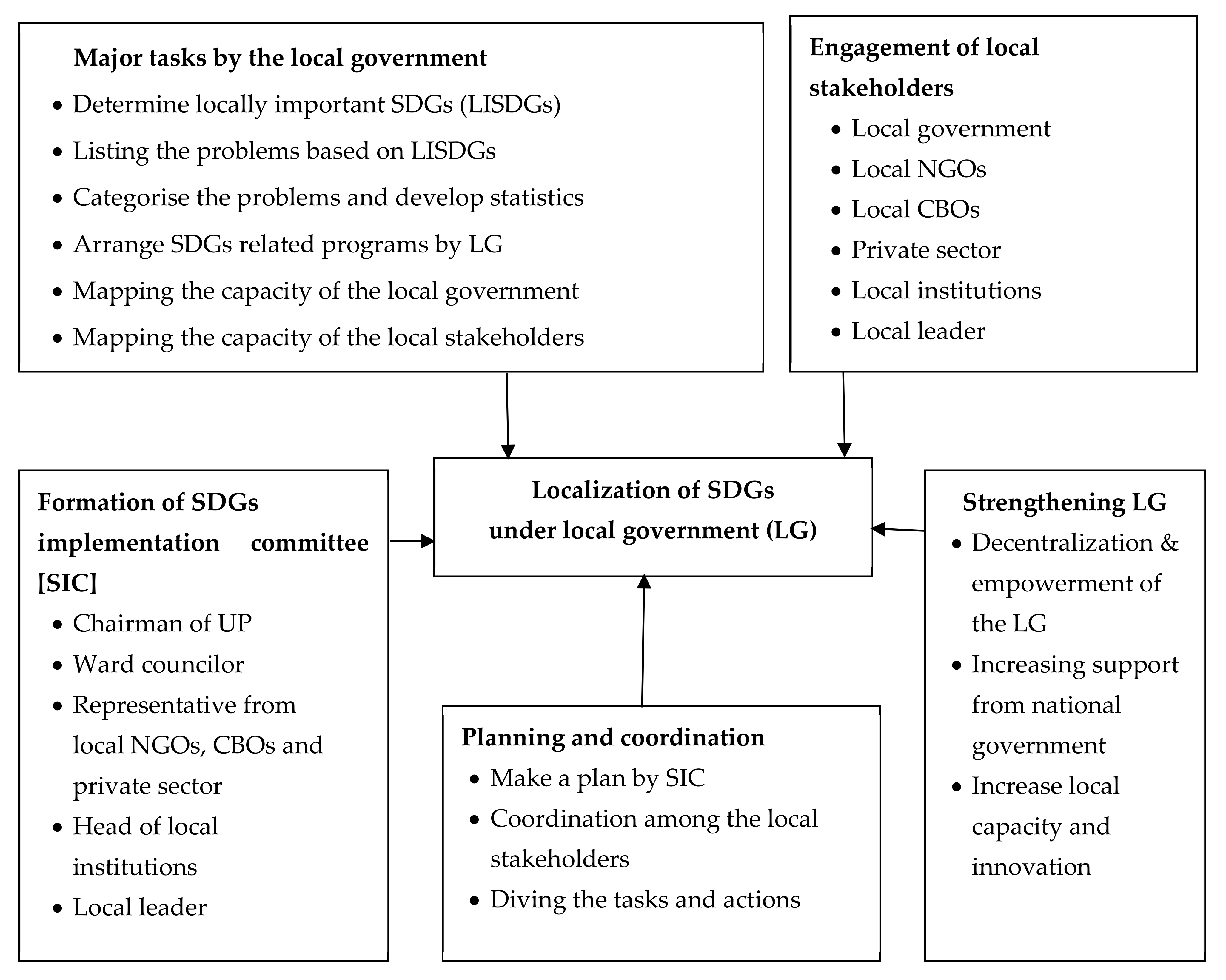

4.4. Inclusive Framework for SDG Localisation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Satterhwaite, D.; Mitlin, D. Urban Poverty in the Global South; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lucci, P. “Localising” the Post-2015 Agenda: What Does It Mean in Practice; Overseas Development Institute: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Oosterhof, P.D. Localising the Sustainable Development Goals to Accelerate Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 2018. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/2325Knowledge%20Management%20Strategy%20for%20Localizing%20SDGs%20at%20National%20Levels.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2021).

- Islam, M.T. Towards the Localisation of the SDGs. The Daily Star. 12 February 2020. Available online: https://www.thedailystar.net/supplements/29th-anniversary-supplements/governance-development-and-sustainable-bangladesh/news/towards-the-localisation-the-sdgs-1866547 (accessed on 16 August 2020).

- Stafford-Smith, M.; Griggs, D.; Gaffney, O.; Ullah, F.; Reyers, B.; Kanie, N.; Stigson, B.; Shrivastava, P.; Leach, M.; O’Connell, D. Integration: The key to implementing the Sustainable Development Goals. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 911–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dube, K. Sustainable Development Goals Localisation in the Hospitality Sector in Botswana and Zimbabwe. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiuzzaman; Rashid, M.R.; Sarkar, M.S.K. Development Transition from Least Developed Country (LDC) to Developing Country: Current progress and challenges of Bangladesh. Int. J. Dev. Res. 2018, 8, 22812–22818. [Google Scholar]

- Panday, P.K. Local government system in Bangladesh: How far is it decentralised? Lex Localis-J. Local Self-Gov. 2011, 9, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, S.A.; Hasan, G.S. Local Government in Bangladesh: Constitutional Provisions and Reality. Metrop. Univ. J. 2019, 4, 136–147. [Google Scholar]

- GUNi. Sustainable Development Goals: Actors and Implementation. A Report from the International Conference. 2018. Available online: http://www.guninetwork.org/files/guni_sdgs_report.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Bexell, M.; Jönsson, K. January. Responsibility and the United Nations’ sustainable development goals. Forum Dev. Stud. 2016, 44, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griggs, D.; Stafford-Smith, M.; Gaffney, O.; Rockström, J.; Öhman, M.C.; Shyamsundar, P.; Steffen, W.; Glaser, G.; Kanie, N.; Noble, I. Sustainable development goals for people and planet. Nature 2013, 495, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griggs, D.; Smith, M.S.; Rockström, J.; Öhman, M.C.; Gaffney, O.; Glaser, G.; Kanie, N.; Noble, I.; Steffen, W.; Shyamsundar, P. An integrated framework for sustainable development goals. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boas, I.; Biermann, F.; Kanie, N. Cross-sectoral strategies in global sustainability governance: Towards a nexus approach. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2016, 16, 449–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. Eradicate Poverty and Transform Economies through Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Available online: http://www.un.org/sg/management/pdf/HLP_P2015_Report.pdf (accessed on 7 March 2021).

- Van Zeijl-Rozema, A.; Cörvers, R.; Kemp, R.; Martens, P. Governance for sustainable development: A framework. Sustain. Dev. 2008, 16, 410–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, K.J.; Cradock-Henry, N.A.; Koch, F.; Patterson, J.; Häyhä, T.; Vogt, J.; Barbi, F. Implementing the “Sustainable Development Goals”: Towards addressing three key governance challenges—Collective action, trade-offs, and accountability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 26, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, F.; Stevens, C.; Bernstein, S.; Gupta, A.; Kabiri, N. Integrating Governance into the Sustainable Development Goals; United Nations University Institute for the Advanced Study of Sustainability: Tokyo, Japan, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Biermann, F.; Kanie, N.; Kim, R.E. Global governance by goal-setting: The novel approach of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2017, 26, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadowcroft, J. Who is in charge here? Governance for sustainable development in a complex world. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2007, 9, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, L.M.; Newig, J. Governance for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: How important are participation, policy coherence, reflexivity, adaptation and democratic institutions? Earth Syst. Gov. 2019, 2, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanie, N.; Biermann, F. Governing through Goals: Sustainable Development Goals as Governance Innovation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, J.D. From millennium development goals to sustainable development goals. Lancet 2012, 379, 2206–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Taskforce of Local and Regional Governments, UNDP, UN-Habitat Roadmap for Localising the SDGs: Implementation and Monitoring at Subnational Level. 2016. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/commitments/818_11195_commitment_ROADMAP%20LOCALIZING%20SDGS.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Jones, P.; Comfort, D. A commentary on the localisation of the sustainable development goals. J. Public Aff. 2019, e1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immler, N.L.; Sakkers, H. The UN-Sustainable Development Goals going local: Learning from localising human rights. Int. J. Hum. Rights 2022, 26, 262–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Z.; Greyling, S.; Simon, D.; Arfvidsson, H.; Moodley, N.; Primo, N.; Wright, C. Local responses to global sustainability agendas: Learning from experimenting with the urban sustainable development goal in Cape Town. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 785–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morén-Alegret, R.; Fatorić, S.; Wladyka, D.; Mas-Palacios, A.; Fonseca, M.L. Challenges in achieving sustainability in Iberian rural areas and small towns: Exploring immigrant stakeholders’ perceptions in Alentejo, Portugal, and Empordà, Spain. J. Rural. Stud. 2018, 64, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyer, J.D.; Bohl, D.K. Alternative pathways to human development: Assessing trade-offs and synergies in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Futures 2019, 105, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, C.; Warchold, A.; Pradhan, P. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): Are we successful in turning trade-offs into synergies? Palgrave Commun. 2019, 5, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moallemi, E.A.; Malekpour, S.; Hadjikakou, M.; Raven, R.; Szetey, K.; Ningrum, D.; Dhiaulhaq, A.; Bryan, B.A. Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals requires transdisciplinary innovation at the local scale. One Earth 2020, 3, 300–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cities, U. The Sustainable Development Goals: What Local Governments Need to Know; United Cities and Local Governments: Barcelona, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Galli, A.; Đurović, G.; Hanscom, L.; Knežević, J. Think globally, act locally: Implementing the sustainable development goals in Montenegro. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 84, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engström, R.E.; Destouni, G.; Howells, M.; Ramaswamy, V.; Rogner, H.; Bazilian, M. Cross-scale water and land impacts of local climate and energy policy—A local Swedish analysis of selected SDG interactions. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GoB. Millennium Development Goals: End-period Stocktaking and Final Evaluation Report (2000–2015); General Economics Division (GED), Bangladesh Planning Commission, Ministry of Planning, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2016.

- Ahmed, B. Environmental governance and sustainable development in Bangladesh: Millennium development goals and sustainable development goals. Asia Pac. J. Public Adm. 2019, 41, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Planning. Sustainable Development Goals: Bangladesh Progress Report 2018; General Economics Division (GED), Bangladesh Planning Commission, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2018.

- Alam, S. SDG Implementation: Ensuring Localisation and Inclusiveness. The Financial Express, 3 October 2018. Available online: https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/views/analysis/sdg-implementation-ensuring-localisation-and-inclusiveness-1538579515 (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Nilsson, M.; Griggs, D.; Visbeck, M. Policy: Map the interactions between Sustainable Development Goals. Nature 2016, 534, 320–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S. SDGs Implementation: Where does Bangladesh Stand? The Financial Express 7 December 2019. Available online: https://www.thefinancialexpress.com.bd/views/views/sdgs-implementation-where-does-bangladesh-stand-1575730124 (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Report 2021 The Decade of Action for the Sustainable Development Goals. Ranking. 2021. Available online: https://dashboards.sdgindex.org/rankings (accessed on 12 January 2022).

- Bhattacharya, S.; Patro, S.A.; Rathi, S. Creating Inclusive cities: A review of indicators for measuring sustainability for urban infrastructure in India. Environ. Urban. ASIA 2016, 7, 214–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatun, F.; Bhattacharya, D.; Rahman, M.; Moazzem, K.G.; Khan, T.I.; Sabbih, M.A.; Saadat, S.Y. Four Years of SDGs in Bangladesh: Measuring Progress and Charting the Path Forward; Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD) and Citizen’s Platform for SDGs: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Talukdar, M.R.I. Rural Local Government in Bangladesh, “Conceptual Framework”; Osder Publications 6–7: Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, V. Reconciling global aspirations and local realities: Challenges facing the Sustainable Development Goals for water and sanitation. World Dev. 2019, 118, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, H.; Okitasari, M.; Morita, K.; Katramiz, T.; Shimizu, H.; Kawakubo, S.; Kataoka, Y. SDGs mainstreaming at the local level: Case studies from Japan. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 1539–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonsu, N.O.; TyreeHageman, J.; Kele, J. Beyond agenda 2030: Future-oriented mechanisms in localising the sustainable development goals (SDGs). Sustainability 2020, 12, 9797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Chen, J.; Li, J. Rural innovation system: Revitalize the countryside for a sustainable development. J. Rural. Stud. 2022, 93, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, S.; Guerrero, P.; Albert, C. Advancing Sustainable Development Goals with localised nature-based solutions: Opportunity spaces in the Lahn river landscape, Germany. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 309, 114696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M. Transition toward Green Economy: Technological Innovation’s Role in the Fashion Industry. Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 2022, 37, 100657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.; Metternicht, G.; Wiedmann, T. Initial progress in implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A review of evidence from countries. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1453–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, T.; Kenawy, E.; Abdrabo, K.I.; Shaw, D.; Alshamndy, A.; Elsharif, M.; Salem, M.; Alwetaishi, M.; Aly, R.M.; Elboshy, B. Voluntary Local Review Framework to Monitor and Evaluate the Progress towards Achieving Sustainable Development Goals at a City Level: Buraidah City, KSA and SDG11 as A Case Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M.; Zhang, Q.; Sroufe, R.; Ferasso, M. Contribution of certification bodies and sustainability standards to sustainable development goals: An integrated grey systems approach. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 326–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| MDGs | Target | Status/Achievement | Status of the Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Goal 1: Eradicate Extreme Poverty and Hunger | 29% [People below the national poverty line] | 24.8% | Goal met |

| Goal 2: Achieve Universal Primary Education | 100% [Net enrolment ratio in primary education] | 98% | Goal met |

| Goal 3: Promote Gender Equality and Empower Women | 1.0 [Ratio of girls to boys in primary education] | 1.04 | Goal met |

| Goal 4: Reduce Child Mortality | 48 [Under-five mortality rate (per 1000 live births)] | 36 | Goal met |

| 31 [Infant (0–1 year) mortality rate (per 1000 live births)] | 29 | ||

| Goal 5: Improve Maternal Health | 143 [Maternal mortality ratio (per 100,000 live births)] | 176 | Substantial progress |

| Goal 6: Combat HIV/AIDS, Malaria, and Other Diseases | Halting [HIV prevalence among population (%)] | <0.1 | On track |

| 0.6 [Deaths from malaria per 100,000 of the population] | 0.34 | Goal met | |

| Goal 7: Ensure Environmental Sustainability | 20% Forest area | 13.4% | Substantial progress |

| 100% [percentage of population using improved sanitation] | 73.5% | ||

| Goal 8: Develop a Global Partnership for Development | Further develop an open, rule-based, predictable, and non-discriminatory trading and financial system | - | Needs attention |

| SDG | Bangladesh’s Performance on SDGs from 2015 to 2021 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| On Track/Maintaining Achievement of SDGs | Moderately Improving | Stagnating | Decreasing | Information Unavailable | |

| SDG 1 | √ | ||||

| SDG 2 | √ | ||||

| SDG 3 | √ | ||||

| SDG 4 | √ | ||||

| SDG 5 | √ | ||||

| SDG 6 | √ | ||||

| SDG 7 | √ | ||||

| SDG 8 | √ | ||||

| SDG 9 | √ | ||||

| SDG 10 | √ | ||||

| SDG 11 | √ | ||||

| SDG 12 | √ | ||||

| SDG 13 | √ | √ | |||

| SDG 14 | √ | ||||

| SDG 15 | √ | ||||

| SDG 16 | √ | ||||

| SDG 17 | √ | ||||

| Level of LG | Location | Name | Headed by | Method of Election |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rural area | ||||

| Uppermost Tier | District | Zila Parisod (District Council) | Elected Chairman | Indirect Election |

| Middle Tier or Central Point | Upazila | UpazilaParisod(UpazilaCouncil) | Elected Chairman | Direct Election |

| Lowest Tier | Union | Union Parisod (Union Council) | Elected Chairman | Direct Election |

| Urban area | ||||

| Mega-City | City Corporation | City Corporation | Elected Mayor | Direct Election |

| Small Town/City | Paurashava (Municipality) | Paurashava (Municipality) | Elected Mayor | Direct Election |

| Knowledge and Participation Relating to the SDGs | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Familiarity with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) | 10 | 0 |

| Participated in SDG-related programmes | 10 | 0 |

| Workshop | 2 | 8 |

| Awareness raising | 6 | 4 |

| Seminar | 2 | 8 |

| Organised awareness-raising programmes relating to SDGs in your organization | 2 | 8 |

| Read SDG-related documents | 10 | 0 |

| Newspaper | 3 | 7 |

| Policy documents | 6 | 4 |

| Leaflets | 4 | 6 |

| Seen or observed SDG-related programmes | 6 | 4 |

| TV (4) | 4 | 6 |

| Video presentation (2) | 2 | 8 |

| Willingness to study more about the SDGs | 10 | 0 |

| Willingness to attend any programmes related to the SDGs | 10 | 0 |

| Willingness to make your village’s people more familiar with the SDGs | 8 | 2 |

| Specific measures applied to promote local development | 1 | 9 |

| Perception Relating to the SDGs | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| SDGs are a crucial development agenda for any country | 10 | 0 |

| SDGs are considered important for local communities and LGs | 10 | 0 |

| SDGs are important for environmental protection | 9 | 0 |

| The government is committed to achieving the SDGs by 2030 | 8 | 0 |

| Local government can significantly contribute to achieving the SDGs | 10 | 0 |

| The SDGs should be taught in schools/Universities | 8 | 2 |

| Satisfaction with the programme currently undertaken at the local level for the SDGs | 4 | 6 |

| Government should give priority to the LGs to speed up SDG achievement | 10 | 0 |

| The government actions are sufficient for SDG achievement | 4 | 6 |

| Type of Programmes | Description of Programmes | Relation with SDGs | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poverty reduction |

| SDG 1 and SDG 2 | 10 | 0 |

| 10 | 0 | |||

| 10 | 0 | |||

| 09 | 1 | |||

| Health services |

| SDG 3 | 08 | 0 |

| 02 | 8 | |||

| 07 | 3 | |||

| 08 | 2 | |||

| 06 | 4 | |||

| Education |

| SDG 4 | 10 | 0 |

| 08 | 2 | |||

| 09 | 1 | |||

| 10 | 0 | |||

| Water and sanitation |

| SDG 6 | 10 | 0 |

| 10 | 0 | |||

| Agricultural service |

| SDG 12 | 10 | 0 |

| 10 | 0 | |||

| 10 | 0 | |||

| Training and employment |

| SDG 10 | 09 | 0 |

| 06 | 4 | |||

| 09 | 1 | |||

| 08 | 2 | |||

| Roads and communication |

| SDG 9 | 10 | 0 |

| 10 | 0 | |||

| 06 | 4 | |||

| Environmental actions |

| SDG 13 | 05 | 5 |

| 08 | 2 | |||

| Other programmes |

| - | 10 | 0 |

| 10 | 0 | |||

| 10 | 0 |

| Resources | Types | |

|---|---|---|

| Personnel (number) | Chairman | 01 |

| Ward Councillor (nine wards) | 12 | |

| Secretary | 01 | |

| Accountant cum computer operator | 01 | |

| Security (Gram police/village police) | 10 | |

| Digital Centre | Union Digital Centre (UDC) | |

| Sources of income | Holding tax | |

| Ijarah or contract of public property | ||

| Income from the rural market | ||

| Income from license provision | ||

| Income from various certificate provision | ||

| Other taxes | ||

| Office/building | Union Parisod building | |

| Local Government Involvement in the Policy Process | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Opportunities to become involved in the policymaking process with the national government | 10 | 0 |

| Access to local MPs (Members of parliament) any time when needed | 10 | 0 |

| Access to the DC (Deputy Commissioner) any time when needed | 09 | 0 |

| Access to a UNO (Upazila Nirbahi Officer) any time when needed | 10 | 0 |

| Attend the meeting arranged by the Upazila Parisod | 10 | 0 |

| Attend the meeting arranged by the Deputy Commissioner | 09 | 0 |

| Government should formulate policy based on LGs’ suggestions | 10 | 0 |

| Dimension of SWOT | Local Government Attributes | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strengths |

| 10 | 0 |

| 10 | 0 | ||

| 10 | 0 | ||

| Opportunities |

| 10 | 0 |

| 9 | 1 | ||

| 10 | 0 | ||

| Weaknesses |

| 10 | 0 |

| 10 | 0 | ||

| 5 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 4 | ||

| 10 | 0 | ||

| Threats |

| 8 | 2 |

| 2 | 8 | ||

| 6 | 4 | ||

| 6 | 4 | ||

| 8 | 2 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarkar, M.S.K.; Okitasari, M.; Ahsan, M.R.; Al-Amin, A.Q. Localisation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Bangladesh: An Inclusive Framework under Local Governments. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10817. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710817

Sarkar MSK, Okitasari M, Ahsan MR, Al-Amin AQ. Localisation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Bangladesh: An Inclusive Framework under Local Governments. Sustainability. 2022; 14(17):10817. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710817

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarkar, Md. Sujahangir Kabir, Mahesti Okitasari, Md. Rajibul Ahsan, and Abul Quasem Al-Amin. 2022. "Localisation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Bangladesh: An Inclusive Framework under Local Governments" Sustainability 14, no. 17: 10817. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710817