Extending the Lifetime of Clothing through Repair and Repurpose: An Investigation of Barriers and Enablers in UK Citizens

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- What is the current behaviour with respect to clothing repair and repurpose among UK citizens?

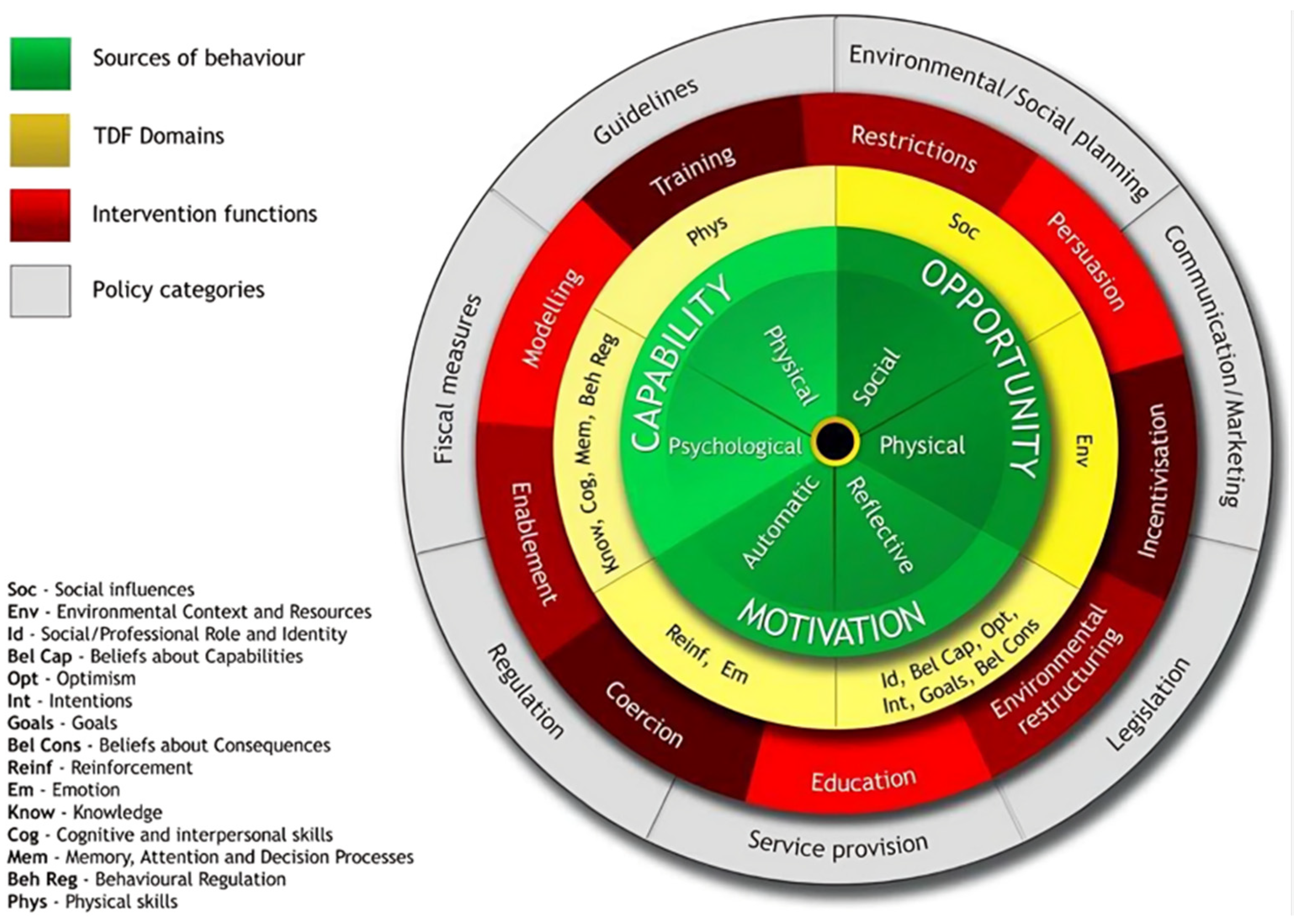

- Using the TDF, what are the main barriers and enablers to clothing repair and repurpose in UK citizens?

- Using the BCW approach, what intervention types, policy options, and behaviour change techniques can facilitate clothing repair and repurpose in UK citizens?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. TDF Scale Development

2.4. Survey Measures

- Demographics. Participants supplied their age, gender, ethnicity, and UK region of residence based on Census 2021 [51].

- Clothing Repair and Repurpose Current Behaviour. Participants responded to two items. The first item asked about their current behaviour: “During COVID-19, over the past year, how often did you repair and repurpose your existing clothes, instead of disposing of them and buying new clothes?” Participants were prompted to think about the period from March 2020 to June 2021. The second item asked: “Before COVID-19, over the course of a typical year, how often did you repair and repurpose your existing clothes, instead of disposing of them and buying new clothes?” Participants were prompted to think about before restrictions imposed in March 2020. Response options for both items were: (1) Never, (2) About once a year, (3) About once every six months, (4) About once a month, and (5) About once a week.

- Clothing Repair and Repurpose Intentions. One item asked what participants intended to do after COVID-19 restrictions were removed (“In the future, I intend to repair and repurpose my existing clothes, instead of disposing of them and buying new clothes...”). Response options were: (1) a lot less than before COVID-19, (2) a little less than before COVID-19, (3) about the same as before COVID-19, (4) a little more than before COVID-19, or (5) a lot more than before COVID-19.

- Influences on Clothing Repair and Repurpose Behaviour. Participants responded to the 40-item TDF scale using a 5-point Likert scale from (1) Strongly disagree to (5) Strongly agree. In addition, we asked a free-text item: “Please tell us your reasons for why you do or do not repair and repurpose your clothes”. This item was included for the purposes of data triangulation (consistent findings across multiple approaches may increase validity) [52] and to identify factors important to participants that may not fit within TDF domains [53].

- Clothing Repair and Repurpose Tasks (adapted from [12,26]). This section asked participants how likely they would repair or repurpose clothing in different ways. A total of 10 items were presented, such as sewing on a button, and adjusting sizing. Participants responded using a 5-point Likert scale from (1) Extremely unlikely to (5) Extremely likely.

2.5. Procedures

2.6. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary Analyses and Demographics

3.2. What Is the Current Behaviour with Respect to Clothing Repair and Repurpose?

3.3. What Are the Main Barriers and Enablers to Clothing Repair and Repurpose?

3.3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.3.2. Regression Analysis

3.3.3. Qualitative Analysis

3.4. What Intervention Types, Policy Options, and Behaviour Change Techniques Can Facilitate Clothing Repair and Repurpose?

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Niinimäki, K.; Peters, G.; Dahlbo, H.; Perry, P.; Rissanen, T.; Gwilt, A. The Environmental Price of Fast Fashion. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, J.; Nielsen, K.S.; Birkved, M.; Joanes, T.; Gwozdz, W. The Environmental Impacts of Clothing: Evidence from United States and Three European Countries. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 2153–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, G.; Li, M.; Lenzen, M. The Need to Decelerate Fast Fashion in a Hot Climate—A Global Sustainability Perspective on the Garment Industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen MacArthur Foundation. A New Textiles Economy: Redesigning Fashion’s Future. Available online: https://ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/a-new-textiles-economy (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- European Environment Agency. Textiles and the Environment in a Circular Economy. Available online: https://www.eionet.europa.eu/etcs/etc-wmge/products/etc-reports/textiles-and-the-environment-in-a-circular-economy/@@download/file/ETC-WMGE_report_final%20for%20website_updated%202020.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Waste & Resources Action Programme. European Clothing Action Plan: Driving Circular Fashion and Textiles. Available online: https://wrap.org.uk/sites/default/files/2021-03/WRAP-ECAP-Summary-Report%202019-Driving-circular-fashion-and-textiles.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Environmental Audit Committee. Fixing Fashion: Clothing Consumption and Sustainability. Available online: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmenvaud/1952/1952.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Nielsen, K.S.; Clayton, S.; Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Capstick, S.; Whitmarsh, L. How Psychology Can Help Limit Climate Change. Am. Psychol. 2020, 76, 130–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L.; Hoolohan, C.; Larner, O.; McLachlan, C.; Poortinga, W. How Has COVID-19 Impacted Low-Carbon Lifestyles and Attitudes towards Climate Action? CAST Briefing Paper 04. Available online: https://cast.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/CAST-Briefing-04-Covid-low-carbon-choices-1.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Iran, S.; Joyner Martinez, C.M.; Vladimirova, K.; Wallaschkowski, S.; Diddi, S.; Henninger, C.E.; McCormick, H.; Matus, K.; Niinimäki, K.; Sauerwein, M.; et al. When Mortality Knocks: Pandemic-Inspired Attitude Shifts towards Sustainable Clothing Consumption in Six Countries. Int. J. Sustain. Fash. Text. 2022, 1, 9–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L. Tracking the Effect of COVID-19 on Low-Carbon Behaviours and Attitudes to Climate Change: Results from Wave 2 of the CAST COVID-19 Survey. CAST Briefing Paper 05. Available online: https://cast.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/CAST-Briefing-05.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Waste & Resources Action Programme. Valuing Our Clothes: The Cost of UK Fashion. Available online: https://wrap.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-10/WRAP-valuing-our-clothes-the-cost-of-uk-fashion_WRAP.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Laitala, K.; Klepp, I.G. Motivations for and against Second-Hand Clothing Acquisition. Cloth. Cult. 2018, 5, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diddi, S.; Yan, R.-N. Consumer Perceptions Related to Clothing Repair and Community Mending Events: A Circular Economy Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitala, K. Consumers’ Clothing Disposal Behaviour—A Synthesis of Research Results. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.H.; Yeap, J.A.L.; Al-Kumaim, N.H. Sustainable Fashion Consumption: Advocating Philanthropic and Economic Motives in Clothing Disposal Behaviour. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, K.Y.H.; Kozar, J.M. Environmentally Sustainable Clothing Consumption: Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behavior. In Roadmap to Sustainable Textiles and Clothing; Muthu, S.S., Ed.; Textile Science and Clothing Technology; Springer: Singapore, 2014; pp. 41–61. ISBN 978-981-287-109-1. [Google Scholar]

- Norum, P.S. Examination of Apparel Maintenance Skills and Practices: Implications for Sustainable Clothing Consumption. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2013, 42, 124–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor-Crabb, A.; Rigby, E.D. Garment Quality and Sustainability: A User-Based Approach. Fash. Pract. 2019, 11, 346–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitala, K.; Klepp, I.G. Care and Production of Clothing in Norwegian Homes: Environmental Implications of Mending and Making Practices. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janigo, K.A.; Wu, J. Collaborative Redesign of Used Clothes as a Sustainable Fashion Solution and Potential Business Opportunity. Fash. Pract. 2015, 7, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, C.M.; Niinimäki, K.; Kujala, S.; Karell, E.; Lang, C. Sustainable Product-Service Systems for Clothing: Exploring Consumer Perceptions of Consumption Alternatives in Finland. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 97, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goworek, H.; Fisher, T.; Cooper, T.; Woodward, S.; Hiller, A. The Sustainable Clothing Market: An Evaluation of Potential Strategies for UK Retailers. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2012, 40, 935–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, K. Mending. In Routledge Handbook of Sustainability and Fashion; Routledge: London, UK, 2014; pp. 262–272. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, F.; Roby, H.; Dibb, S. Sustainable Clothing: Challenges, Barriers and Interventions for Encouraging More Sustainable Consumer Behaviour. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2016, 40, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitala, K.; Boks, C. Sustainable Clothing Design: Use Matters. J. Des. Res. 2012, 10, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twigger Holroyd, A. Perceptions and Practices of Dress-Related Leisure: Shopping, Sorting, Making and Mending. Ann. Leis. Res. 2016, 19, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, D.; Silverman, J.; Dickson, M.A. Consumer Interest in Upcycling Techniques and Purchasing Upcycled Clothing as an Approach to Reducing Textile Waste. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2019, 12, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrani, M. “People Gather for Stranger Things, So Why Not This?” Learning Sustainable Sensibilities through Communal Garment-Mending Practices. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martindale, A.; McKinney, E. Why Do They Sew? Women’s Motivations to Sew Clothing for Themselves. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2020, 38, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapolla, K.; Sanders, E.B.-N. Using Cocreation to Engage Everyday Creativity in Reusing and Repairing Apparel. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 2015, 33, 183–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, L.S.; Hamlin, R.P.; McQueen, R.H.; Degenstein, L.; Garrett, T.C.; Dunn, L.; Wakes, S. Fashion Sensitive Young Consumers and Fashion Garment Repair: Emotional Connections to Garments as a Sustainability Strategy. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2020, 44, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwilt, A. What Prevents People Repairing Clothes? An Investigation into Community-Based Approaches to Sustainable Product Service Systems for Clothing Repair. Mak. Futures J. 2014, 3. Available online: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/8125/ (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- McLaren, A.; McLauchlan, S. Crafting Sustainable Repairs: Practice-Based Approaches to Extending the Life of Clothes; Nottingham Trent University: Nottingham, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, K.; Cooper, T.; Oehlmann, J.; Singh, J.; Mont, O. Multi-Stakeholder Perspectives on Scaling up UK Fashion Upcycling Businesses. Fash. Pract. 2020, 12, 331–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bly, S.; Gwozdz, W.; Reisch, L.A. Exit from the High Street: An Exploratory Study of Sustainable Fashion Consumption Pioneers. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparkman, G.; Walton, G.M. Dynamic Norms Promote Sustainable Behavior, Even If It Is Counternormative. Psychol. Sci. 2017, 28, 1663–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.V.; Nguyen, C.H.; Hoang, T.T.B. Green Consumption: Closing the Intention-Behavior Gap. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 27, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P.; Webb, T.L. The Intention–Behavior Gap. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 2016, 10, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, T.; Rundle-Thiele, S. Are We Speaking the Same Language? Call for Action to Improve Theory Application and Reporting in Behaviour Change Research. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L.; Poortinga, W.; Capstick, S. Behaviour Change to Address Climate Change. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2021, 42, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmarsh, L.; Capstick, S.; Nash, N. Who Is Reducing Their Material Consumption and Why? A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Dematerialization Behaviours. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2017, 375, 20160376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A New Method for Characterising and Designing Behaviour Change Interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cane, J.; O’Connor, D.; Michie, S. Validation of the Theoretical Domains Framework for Use in Behaviour Change and Implementation Research. Implement. Sci. 2012, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkins, L.; Francis, J.; Islam, R.; O’Connor, D.; Patey, A.; Ivers, N.; Foy, R.; Duncan, E.M.; Colquhoun, H.; Grimshaw, J.M.; et al. A Guide to Using the Theoretical Domains Framework of Behaviour Change to Investigate Implementation Problems. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Richardson, M.; Johnston, M.; Abraham, C.; Francis, J.; Hardeman, W.; Eccles, M.P.; Cane, J.; Wood, C.E. The Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy (v1) of 93 Hierarchically Clustered Techniques: Building an International Consensus for the Reporting of Behavior Change Interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 46, 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundimu, E.O.; Altman, D.G.; Collins, G.S. Adequate Sample Size for Developing Prediction Models Is Not Simply Related to Events per Variable. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 76, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijg, J.M.; Gebhardt, W.A.; Dusseldorp, E.; Verheijden, M.W.; van der Zouwe, N.; Middelkoop, B.J.; Crone, M.R. Measuring Determinants of Implementation Behavior: Psychometric Properties of a Questionnaire Based on the Theoretical Domains Framework. Implement. Sci. 2014, 9, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, N.; Lawton, R.; Conner, M. Development and Initial Validation of the Determinants of Physical Activity Questionnaire. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2013, 10, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, T.; Cooper, T.; Woodward, S.; Hiller, A.; Goworek, H. Public Understanding of Sustainable Clothing: A Report to the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313479526_Public_Understanding_of_Sustainable_Clothing_Report_to_the_Department_for_Environment_Food_and_Rural_Affairs (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Office for National Statistics. Census 2021. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/census (accessed on 1 May 2021).

- Munafò, M.R.; Smith, G.D. Robust Research Needs Many Lines of Evidence. Nature 2018, 553, 399–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, L.J.; Powell, R.; French, D.P. How Can Use of the Theoretical Domains Framework Be Optimized in Qualitative Research? A Rapid Systematic Review. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 25, 677–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, H.; Wallace, S.J.; Ryan, B.; Finch, E.; Shrubsole, K. Current Practice and Barriers and Facilitators to Outcome Measurement in Aphasia Rehabilitation: A Cross-Sectional Study Using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Aphasiology 2020, 34, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amemori, M.; Michie, S.; Korhonen, T.; Murtomaa, H.; Kinnunen, T.H. Assessing Implementation Difficulties in Tobacco Use Prevention and Cessation Counselling among Dental Providers. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beenstock, J.; Sniehotta, F.F.; White, M.; Bell, R.; Milne, E.M.; Araujo-Soares, V. What Helps and Hinders Midwives in Engaging with Pregnant Women about Stopping Smoking? A Cross-Sectional Survey of Perceived Implementation Difficulties among Midwives in the North East of England. Implement. Sci. 2012, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patey, A.M.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Francis, J.J. Changing Behaviour, ‘More or Less’: Do Implementation and de-Implementation Interventions Include Different Behaviour Change Techniques? Implement. Sci. 2021, 16, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squires, J.E.; Linklater, S.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Graham, I.D.; Sullivan, K.; Bruce, N.; Gartke, K.; Karovitch, A.; Roth, V.; Stockton, K.; et al. Understanding Practice: Factors That Influence Physician Hand Hygiene Compliance. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2014, 35, 1511–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Atkins, L.; West, R. The Behaviour Change Wheel. A Guide to Designing Interventions; Silverback Publishing: Sutton, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- McParlin, C.; Bell, R.; Robson, S.C.; Muirhead, C.R.; Araújo-Soares, V. What Helps or Hinders Midwives to Implement Physical Activity Guidelines for Obese Pregnant Women? A Questionnaire Survey Using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Midwifery 2017, 49, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagerland, M.W.; Hosmer, D.W. Tests for Goodness of Fit in Ordinal Logistic Regression Models. J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 2016, 86, 3398–3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menard, S. Coefficients of Determination for Multiple Logistic Regression Analysis. Am. Stat. 2000, 54, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitala, K.; Klepp, I.G.; Haugrønning, V.; Throne-Holst, H.; Strandbakken, P. Increasing Repair of Household Appliances, Mobile Phones and Clothing: Experiences from Consumers and the Repair Industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 282, 125349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, F.; Dewitte, S. Measuring Pro-Environmental Behavior: Review and Recommendations. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 63, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janigo, K.A.; Wu, J.; DeLong, M. Redesigning Fashion: An Analysis and Categorization of Women’s Clothing Upcycling Behavior. Fash. Pract. 2017, 9, 254–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimäki, K.; Durrani, M. Repairing Fashion Cultures: From Disposable to Repairable. In Transitioning to Responsible Consumption and Production; MDPI AG: Basel, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 154–168. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, K.S.; Gwozdz, W. Consumer Policy Recommendations. Available online: http://mistrafuturefashion.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/K.-Steensen-Consumer-Policy-Recommendations-mistra-future-fashion-report-2019.10.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Nielsen, K.S.; Brick, C.; Hofmann, W.; Joanes, T.; Lange, F.; Gwozdz, W. The Motivation–Impact Gap in pro-Environmental Clothing Consumption. Nat. Sustain. 2022, 5, 665–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepp, I.G.; Laitala, K.; Wiedemann, S. Clothing Lifespans: What Should Be Measured and How. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs. Waste Prevention Programme for England: Towards a Resource Efficient Economy. Available online: https://consult.defra.gov.uk/waste-and-recycling/waste-prevention-programme-for-england-2021/supporting_documents/Waste%20Prevention%20Programme%20for%20England%20%20consultation%20document.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Nazlı, T. Repair motivation and barriers model: Investigating user perspectives related to product repair towards a circular economy. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 289, 125644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| TDF Domain | No. Items | Example Item | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | 3 | I know how to repair and repurpose my clothes. | Adapted from Diddi and Yan [14] |

| Skills | 3 | I have the physical skills to repair and repurpose my clothes (e.g., dexterity to thread a needle). | Adapted from Huijg et al. [48] |

| Memory, Attention and Decision Processes | 2 | I can focus my attention in order to repair and repurpose my clothes. | Content based on Twigger Holroyd [27] |

| Behavioural Regulation | 2 | I often put off repairing and repurposing my clothes (e.g., not bothered). * | Content based on EAC [7] |

| Social Influences | 4 | I do not repair and repurpose my clothes because other people see it negatively. * | Content based on Gwilt [33] |

| Environmental Context and Resources | 8 | I have the necessary equipment (e.g., sewing machine) to repair and repurpose my clothes. | Content based on Fisher et al. [50] |

| Social/Professional Role and Identity | 2 | Repairing and repurposing things is part of my identity. | Content based on Lapolla and Sanders [31] |

| Beliefs about Capabilities | 1 | I am confident in my abilities to repair and repurpose my clothes. | Adapted from Diddi and Yan [14] |

| Optimism | 1 | I am optimistic that the end result of repairing and repurposing my clothes will be successful. | Adapted from Diddi and Yan [14] |

| Beliefs about Consequences | 2 | I believe that repairing and repurposing my clothes has positive impacts on the environment (e.g., less waste). | Adapted from Diddi and Yan [14] |

| Intentions | 1 | I strongly intend to repair and repurpose my clothes. | Adapted from Diddi and Yan [14] |

| Goals | 2 | A goal of mine is to learn new skills to repair and repurpose my clothes. | Adapted from Bhatt et al. [28] |

| Reinforcement | 4 | I routinely dispose of my clothes instead of repairing and repurposing them. * | Content based on Goworek et al. [23] |

| Emotion | 5 | I repair and repurpose my clothes because I have emotional attachment to them. | Adapted from Diddi and Yan [14] |

| Phase | Steps |

|---|---|

| Phase 1: Familiarisation with data |

|

| Phase 2: Generating initial codes |

|

| Phase 3: Generating initial themes |

|

| Phase 4: Reviewing themes |

|

| Phase 5: Defining and naming themes |

|

| Phase 6: Applying the theoretical framework |

|

| Phase 7: Producing the report |

|

| Demographic | Current Sample |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Mean | 44.52 |

| SD | 15.83 |

| Range | 18–88 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 51.5% |

| Male | 48.1% |

| Other | 0.3% |

| Ethnicity | |

| White | 76.7% |

| Asian/British Asian | 10.7% |

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British | 6.3% |

| Mixed or multiple ethnic groups | 3.0% |

| TDF Domain | M | SD | α * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | 3.42 | 0.83 | 0.46 |

| Skills | 2.72 | 1.03 | 0.70 |

| Memory, Attention, and Decision Processes | 3.22 | 1.40 | - |

| Behavioural Regulation | 2.73 | 1.16 | - |

| Social Influences | 4.14 | 0.77 | 0.62 |

| Environmental Context and Resources | 2.88 | 0.66 | 0.63 |

| Social/Professional Role and Identity | 2.30 | 1.11 | 0.71 |

| Beliefs about Capabilities | 2.89 | 1.39 | - |

| Optimism | 3.33 | 1.23 | - |

| Beliefs about Consequences | 3.98 | 0.83 | 0.51 |

| Intentions | 3.36 | 1.28 | - |

| Goals | 3.02 | 1.10 | 0.71 |

| Reinforcement | 3.13 | 0.87 | 0.64 |

| Emotion | 3.19 | 0.89 | 0.75 |

| Predictor | β | SE (β) | Wald’s χ2 | df | p | Odds Ratio | [95% CI Odds Ratio] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.46 | 1 | 0.50 | 1.15 | [0.77, 1.72] |

| Skills | 0.14 | 0.21 | 0.47 | 1 | 0.49 | 1.15 | [0.77, 1.74] |

| Memory, Attention, and Decision Processes | 0.34 | 0.14 | 5.80 | 1 | 0.02 | 1.40 | [1.07, 1.84] |

| Behavioural Regulation | −0.03 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 1 | 0.80 | 0.97 | [0.78, 1.21] |

| Social Influences | −0.19 | 0.16 | 1.36 | 1 | 0.24 | 0.83 | [0.60, 1.14] |

| Environmental Context and Resources | 0.49 | 0.29 | 2.83 | 1 | 0.09 | 1.63 | [0.92, 2.89] |

| Identity | 0.06 | 0.15 | 0.19 | 1 | 0.67 | 1.07 | [0.80, 1.43] |

| Beliefs about Capabilities | −0.14 | 0.17 | 0.67 | 1 | 0.41 | 0.87 | [0.63, 1.24] |

| Optimism | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 1 | 0.65 | 1.07 | [0.80, 1.42] |

| Beliefs about Consequences | 0.36 | 0.21 | 3.08 | 1 | 0.08 | 1.44 | [0.96, 2.15] |

| Intentions | 0.20 | 0.17 | 1.30 | 1 | 0.25 | 1.22 | [0.87, 1.70] |

| Goals | 0.09 | 0.15 | 0.32 | 1 | 0.57 | 1.09 | [0.81, 1.47] |

| Reinforcement | 0.45 | 0.23 | 3.88 | 1 | 0.04 | 1.57 | [1.00, 2.47] |

| Emotion | 0.10 | 0.24 | 0.16 | 1 | 0.69 | 1.10 | [0.69, 1.77] |

| Test | χ2 | df | p | ||||

| Test of parallel lines for proportional odds assumption | 31.94 | 28 | 0.28 | ||||

| Omnibus test for model fit (Likelihood Ratio) | 170.85 | 14 | <0.001 | ||||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.21 (McFadden R2) | ||||||

| TDF Domain | Theme (n = 18) | Theme Description | Frequency (%) | Barrier/Enabler/Mixed | Example Quote(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | 1. Knowledge of how to repair and repurpose | Knowing how to repair and repurpose, or being aware of services (e.g., tailors) that can assist them | 18 (6.1%) | Barrier | “I dont know how to repair clothes nor do I know someone who can repair clothes” ID 28 |

| 2. Awareness of environmental impacts of clothing | Being aware of the impacts of clothing on the environment, which often translated to behaviour | 7 (2.4%) | Enabler | “I know the majority of clothes end up in landfill so I am trying to reduce the amount of clothes that I have ending up there.” ID 87 | |

| Skills | 3. Skills and skill development | Having the skills to repair and repurpose, often attributed to (lack of) training, creativity, or physical capability | 65 (21.9%) | Barrier | “I don’t have the skills to repurpose or repair my clothes.” ID 46 “I never learnt how to repair fabrics” ID 84 |

| Social influences | 4. Social support | Support from friends and family when one is unable to repair and repurpose themselves | 7 (2.4%) | Enabler | “I usually ask a friend or family member to repair or repurpose an item of my clothing for me if need be.” ID 46 |

| 5. Social feedback and conformity | Receiving negative feedback from others, and perceived social pressure to conform to fashion trends | 10 (3.4%) | Mixed | Barrier: “there were a few occasions where I received negative feedback when I asked people’s opinions which put me off.” ID 33 Enabler: “I am not concerned with items going out of fashion, as I rarely follow fashion trends.” ID 188 | |

| Environmental context and resources | 6. Accessibility to resources | Access to necessary equipment such as a sewing machine and haberdashery supplies | 7 (2.4%) | Mixed | Barrier: “I lack the equipment needed.” ID 287 Enabler: “i have a sewing machine in the house where i can used for repair it.” ID 233 |

| 7. Time constraints | Lack of time to carry out repair and repurpose tasks, particularly since they require considerable time | 22 (7.4%) | Barrier | “i dont repair clothes out of having no time to do it” ID 193 “Too time consuming to repair or repurpose.” ID 160 | |

| 8. Convenience of alternative behaviours | Ease of buying new clothes, and disposing via different routes such as donating, selling, or throwing away | 68 (22.9%) | Barrier | “the convenience of just buying new clothes when old ones have had their time appeals to me more.” ID 84 “I would prefer to hand them on to a more needy cause, or sell them” ID 178 | |

| 9. Economic viability | One perspective is that clothes are cheaper to replace because repair costs are unaffordable, and new items are inexpensive. Another perspective is that repair and repurpose is more economical than replacing | 56 (18.9%) | Mixed | Barrier: “Most of the clothes I buy cost me less than £10, last a couple of years then I buy again, the cost to repair would be more than buying new” ID 121 Enabler: “It makes financial sense to carry out a repair rather than to replace a whole garment.” ID 132 | |

| 10. Characteristics of the item | Characteristics include the item price, material quality and durability, and damage severity (or amount of wear). Expensive, high-quality, durable items, and items with minor damage are more likely to be repaired | 89 (30.0%) | Mixed | Barrier: “Items bought are usually not long lasting and not worth repairing.” ID 119 Enablers: “If an item is expensive or a quality item, I am prepared to invest time repairing or altering.” ID 149 “I repair clothes that still has a life in them that only needs a minor repair, i.e small tears etc.” ID 159 | |

| Reinforcement | 11. Past experiences | Attaching negative associations to repair and repurpose due to past unsuccessful experiences | 3 (1.0%) | Barrier | “tried and end up ruining some item beyond usable” ID 148 |

| 12. Routines | Repair and repurpose was regarded as something one routinely engages in | 6 (2.0%) | Enabler | “It’s something I’ve always done for years.” ID 213 | |

| Emotions | 13. Attachment to clothes and emotions derived | Having an emotional connection with their clothes, valuing them, and enjoying sewing, versus having no attachment and treating clothes as disposable | 57 (19.2%) | Mixed | Barrier: “More common that I go off an item of clothing so discard it.” ID 181 Enablers: “I care about and tend to get attached to objects, so I try to keep a hold of them for as long as possible. This makes it very likely for me to repair something I own.” ID 34 |

| Beliefs about capabilities | 14. Self-efficacy | Confidence in one’s skills, which is moderated by the perceived difficulty or ease of the task | 31 (10.4%) | Mixed | Barrier: “I’m not confident enough to do this myself.” ID 71 Enabler: “I am quite good at sewing, so have the confidence to do this.” ID 249 |

| Beliefs about consequences | 15. Anticipated consequences (outcome expectancies) | Beliefs that repair and repurpose has positive impacts on the environment, get one’s money’s worth, and can improve clothing functionality, aesthetics, and uniqueness | 82 (27.6%) | Mixed | Barrier: “I would also feel that even if it was professionally restored that it will not be as good as it used to be.” ID 22 Enabler: “Repairing an item can extend it’s useful life and represents good value for the time taken.” ID 80 |

| 16. Attitudes | Having a dislike of repaired clothes and seeing it is unworthwhile, versus a dislike of clothing waste and ‘throwaway culture’ | 44 (14.8%) | Mixed | Barrier: “I don’t like to wear something that is repaired.” ID 273 Enabler: “I don’t like waste. I don’t think fast fashion is good for the planet” ID 39 | |

| Intentions | 17. Intentions to repair and repurpose | Interest and willingness to repair and repurpose, including learning new skills | 16 (5.4%) | Mixed | Barrier: “don’t want to do it I guess. Never really crossed my mind.” ID 222 Enabler: “I have recently purchased a sewing machine and now more interested in what I can do with existing clothing items” ID 216 |

| Goals | 18. Resolve to behave pro-environmentally | Personal goals to consume more sustainably, avoid new purchases and landfill, and reduce one’s environmental footprint | 29 (9.8%) | Enabler | “I pledged not to buy new clothes unless absolutely essential about two and a half years ago and would repair clothes if necessary.” ID 99 |

| Barrier/Enabler (TDF Domain) | Intervention Type(s) | Selected BCTs (See [45] for Descriptions and Numbering System) | BCT Operationalisation | Policy Option(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| 5.3 Information about social and environmental consequences 5.2 Salience of consequences |

|

|

|

| 13.5 Identity associated with behaviour change |

|

|

|

| 6.3 Information about others’ approval 9.1 Credible source |

|

|

|

| 6.1 Demonstration of the behaviour 4.1 Instruction on how to perform the behaviour 8.2 Behavioural practice/rehearsal |

|

|

|

| 12.5 Adding objects to the environment 12.1 Restructuring the physical environment |

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Hale, J. Extending the Lifetime of Clothing through Repair and Repurpose: An Investigation of Barriers and Enablers in UK Citizens. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10821. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710821

Zhang L, Hale J. Extending the Lifetime of Clothing through Repair and Repurpose: An Investigation of Barriers and Enablers in UK Citizens. Sustainability. 2022; 14(17):10821. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710821

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Lisa, and Jo Hale. 2022. "Extending the Lifetime of Clothing through Repair and Repurpose: An Investigation of Barriers and Enablers in UK Citizens" Sustainability 14, no. 17: 10821. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710821

APA StyleZhang, L., & Hale, J. (2022). Extending the Lifetime of Clothing through Repair and Repurpose: An Investigation of Barriers and Enablers in UK Citizens. Sustainability, 14(17), 10821. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141710821